Liverpool Town Hall

Liverpool Town Hall

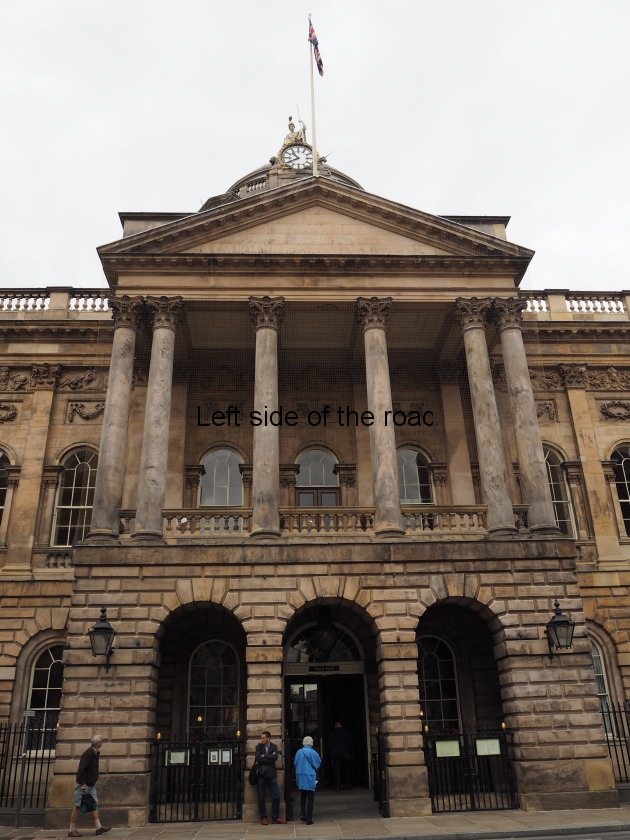

Liverpool Town Hall, one of the oldest buildings in the city, is normally open to the public for a couple of weeks each year. In 2017 that was during the last two weeks of August. Dates for 2018 will be posted when known.

History

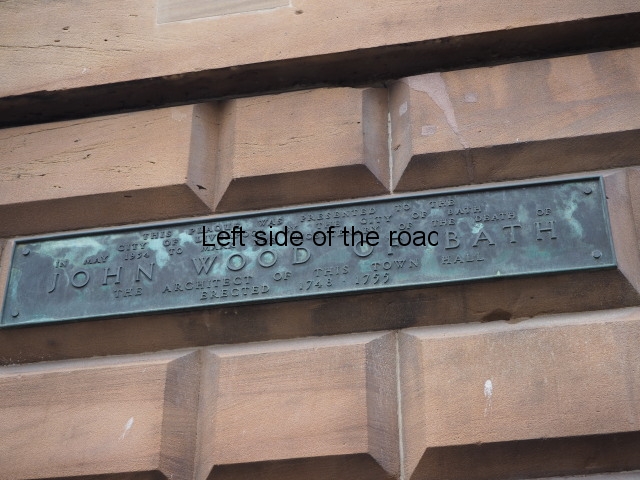

The first Liverpool Town hall was presented to the town in 1515, being little more than an elaborate barn, but it served its purpose for more than 150 years. By the end of the 17th century Liverpool was a much more important place, gaining much of its wealth from the slave trade, and a more substantial building was constructed. However, this had faulty foundations and in 1748 John Woods, an architect from Bath, was commissioned to build Town Hall III and it opened in 1754.

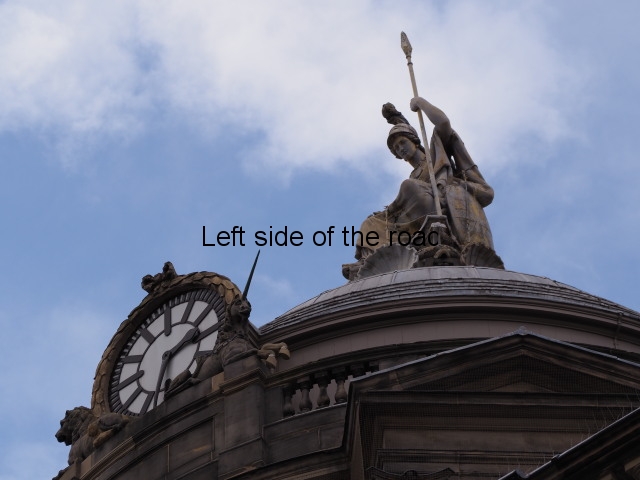

But this was to have the shortest lifespan of them all, as in 1795 a fire broke out and as it was at the time of a severe winter sufficient water couldn’t be brought to the building and the interior was totally destroyed. However, the town now saw itself as of such importance that money was found to commission another architect, this time James Wyatt from London, to completely remodel the inside of the building. The work was completed by 1810, to a design which is basically the Town Hall of today. It underwent an expansion in 1820 when the dome, the large ballroom and the Council Chamber were added.

Interior

Entrance Lobby

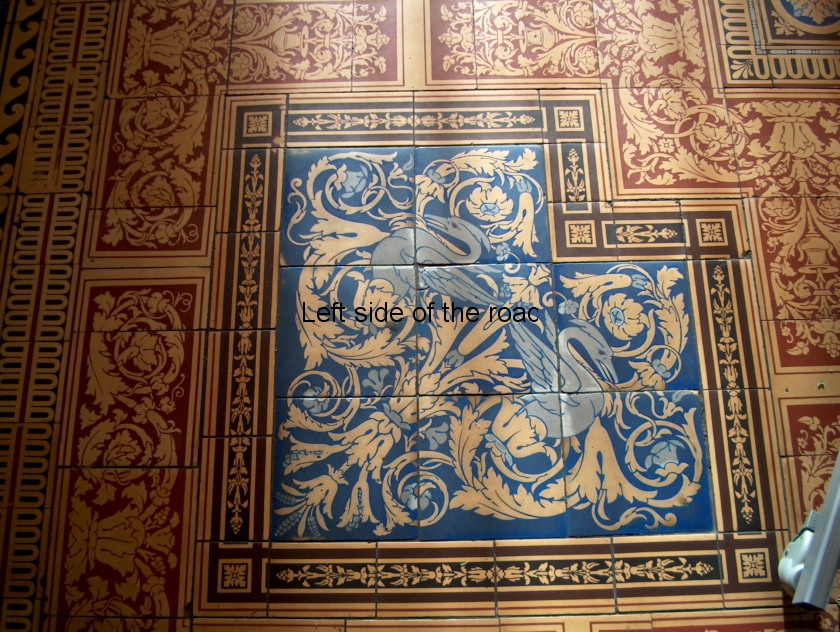

Starting at the main entrance. The tiles on the floor of the entrance lobby are the same as those in St George’s Hall, that is encaustic (the inlaying of coloured clay before baking) Minton tiles. Some of the tiles are starting to show signs of wear (and the reason why the tiled floor in St George’s Hall spends most of its time hidden under a protective wooden floor). The Coat of Arms is still in good condition as very often a table sits on top of it to prevent people walking across the design. Here you’ll also find an image of the famous Liver Bird.

Liver Bird

The fireplace is Flemish and was a gift to the city in 1893. On either side of the fireplace are Bardic chairs from the Eisteddford which used to be held in David Lewis Hotel and Theatre (located close to the Anglican Cathedral before being demolished in 1980) before the WWI. Also in the lobby is the doorman’s chair. There used to be two of them but one was stolen. Underneath the seat the chair is lead lined and hot coals could be placed there to keep the doorman warm. The present seat was refurbished in 1990.

The brass panels around the entrance hall list the names of the people who have been granted the Freedom of the City. The Beatles are listed to the right of the doorway to the stairs.

The lunettes (semi-circular panels) were painted by a local artist, JH Amschewitz and were completed in 1909, as part of the celebrations of the granting of Liverpool’s Charter by King John in 1207 – the event being depicted in the panel on the left. The other panels use the allegory of a woman as representing Liverpool and those aspects which made Liverpool the rich city it was through trade and commerce (but no reference to slavery) such as the ships, a spinning wheel, a cog (a symbol of industry) and exotic fruits. People from different ethnic backgrounds are in the panel over the fireplace.

The Stairway

Through the doors and in a cabinet to the left is one of the finest collections of silverware in the country, including the Civic Regalia. (There’s should be more in the vaults but that’s not certain in times of austerity as selling off of the family silver is a well-known tactic in straitened times.) Much of this silverware is decorated with the Liverpool Coat of Arms and/or The Liver Bird. The large pieces of wood are staves that were used to get carriages out of ruts in the roads and also used as emergency brakes – by pushing them between the spokes of the carriage wheels.

In the display case on the other side there are further articles, the oldest from the late 17th century. These include ‘Nelson’s Sword’. This was due to be presented to him on his next visit to Liverpool but he died at Trafalgar (1805) before that visit could take place. Nelson was a supporter of slavery and that was why there was such a close bond between him and the city.

The cast iron stoves were part of the original heating system. The lamps were made specifically for the Town Hall and are made out of mahogany and cast iron. Originally they would have been powered by gas until the Hall was electrified in 1895.

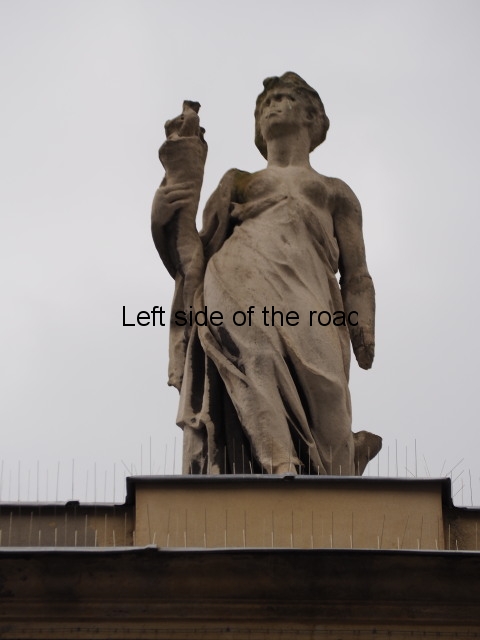

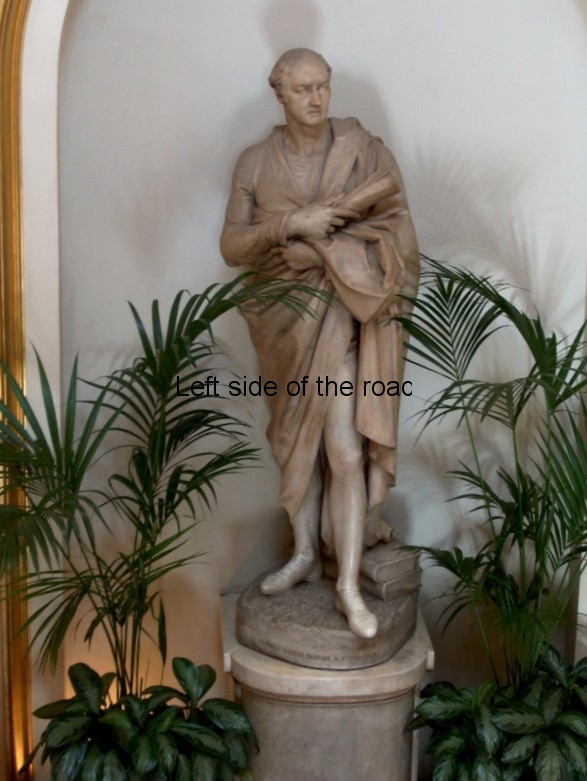

George Canning

The statue at the top of the first flight of stairs is of George Canning, an MP for the town and Prime Minister for 4 months in 1827, was completed in 1832 by Francis Chantrey. He’s dressed in a Roman toga. This is slightly ridiculous but was a common affectation at the time (Liverpool trying to vie with Rome’s ‘greatness’) as can be seen with the statues of William Huskisson (in Dukes Terrace) and George III (in London Road).

The picture of Elizabeth II is by a local (Garston) artist, Edward Halliday and was painted in 1955. On either side of the stairs are portraits of Queen Mary (William Llewllyn, in 1913) and King George V (Luke Fildes, 1910).

The standard holders are for those of the King’s Liverpool Regiment.

The Dome

The impressive dome is 32.3 metres (106 feet) above street level. The wording around the base of the dome is the motto of the City of Liverpool – ‘Deus nobis haec otis fecit’ which is Latin for ‘God has bestowed these blessings upon us’.

Dome

The four pendentives (the triangular corner paintings) are by Charles Furse and show scenes from the docks in the 19th century. (There’s more information on these paintings on the brass on the balustrade at the top of the stairs.)

Plan of First Floor

A. Central Reception Room B. West Reception Room C. Dining Room

D. Large Ballroom E. Small Ballroom F. East Reception Room

Reception Rooms

The entrance to the central reception room is at the top of the stairs. Inside the room the portraits are of George III (‘Mad George’) and his three sons. The stoves were originally from Carlton House in London, the palace used by Victoria before Buckingham Palace was built. What she didn’t want was sent around the country and Liverpool got the stoves. The mirrors on either side of the balcony doors came from Lathom House in Lancashire.

Stove from Carlton House

It was from the balcony that the rebel Labour Councillors addressed the thousands of people in the street below who were demonstrating against Tory cuts way back in 1984 – Tory cuts seem to get away with no (or very little) opposition nowadays

There are two reception rooms off the main one. In the west room (on the right) there is a portrait of James Lord the first American consul to Liverpool. In the 19th century Liverpool had a close relationship with America – especially the Southern Rebel Confederate States during the American Civil War. This was due to Liverpool’s support of slavery (even though it had been abolished in 1807) and the crops that were produced as a result of that economy – sugar, tobacco and cotton – upon which Liverpool made its wealth well into the 20th century.

The east room (on the left) is often referred to as the music room. The paintings are of George Clayton, William Brown, William Gladstone, wealthy 19th century Liverpudlians.

The Small Ballroom

From the east room you enter the Small Ballroom. The portraits on either side of the door you have just come in are of John Bent and his wife, a brewer who became mayor. (Although they are slowly disappearing Bent’s pubs were very often faced with tiling, making them quite distinctive. Bent’s was taken over by Whitbread’s way back in the 1970s.

The wooden flooring is as it would have been originally. After the war, and up until 1990, these rooms were carpeted but during a major renovation in that year it was decided to return the building back to as close to the original as possible. This also meant recreating the colours of the walls of the 18th century. There are also two minstrel galleries – where musicians would entertain the guests.

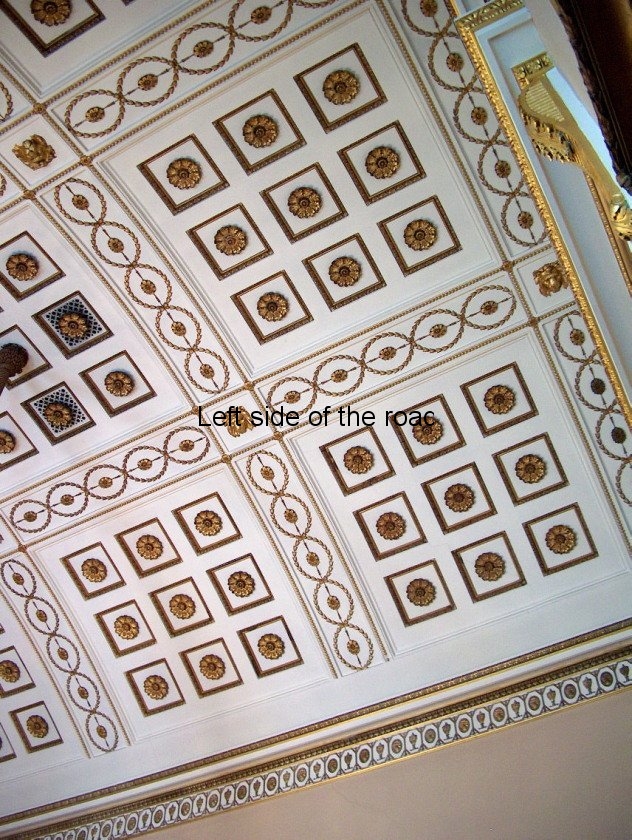

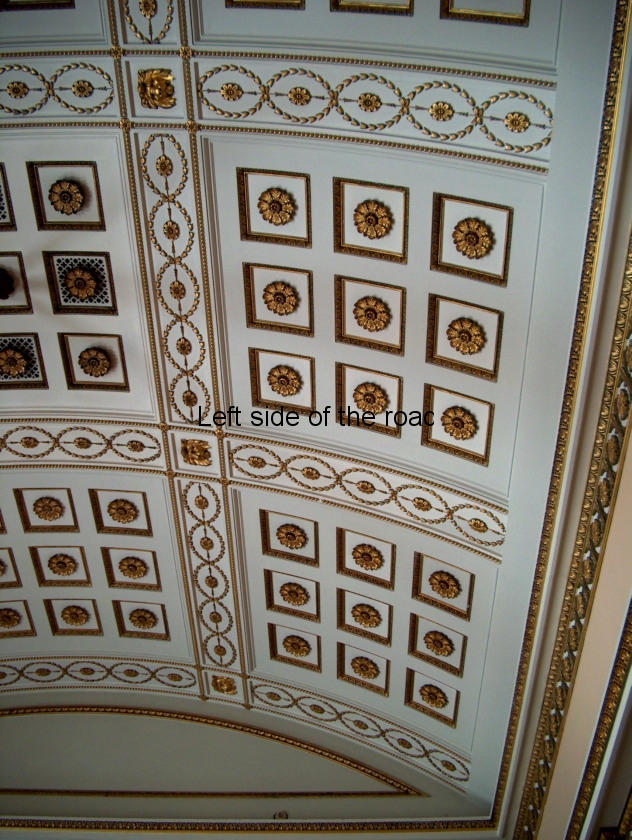

Ceiling Small Ballroom

The chandeliers are all of English crystal and were made in Staffordshire in 1820 and are unique to the Town Hall and they are of different design in each room. The mirrors give an impression of space and also improve the natural lighting. As the function of the room becomes more important so does the decoration and plaster work on the ceilings and friezes.

The Large Ballroom

The next room is the Large Ballroom. It is 27 metres (89 feet) long and 12.8 metres (42 feet) wide with a 12 metre (40 feet) high ceiling. The three chandeliers are each 8.5 metres (28 foot) long, contain 20,000 pieces of cut glass crystal and weigh over one ton.

Chandeliers – Large Ballroom

The room has a sprung maple dance floor specially made for dancing and at each end of the room are two massive mirrors, the largest in any public building in the UK. Over the window facing the entrance door is the coat of arms of the UK and over the door you have just entered the coat of arms of the city of Liverpool.

Off the ballroom the balcony (now at the back of the building) looks out over Exchange Flags – so called as this was where stock trading used to take place up to the middle of the 19th century. Also in the square is the Nelson Monument, designed by Matthew Cotes Wyatt and sculpted by Richard Westmacott, was unveiled in 1813. It also serves as a ventilation shaft for the car park below.

The Dining Room

The next room is the Dining Room. Of particular interest here is the ornate moulded plaster ceiling. The putti (the naked cherubs in the cornices) were covered up for much of the past and were rediscovered and restored during the 1990’s renovation. The cupboards underneath the big alabaster urns on the side of the doors used to be plate warmers. Beneath the window are lead lined cupboards which were used as wine coolers. The table is in sections and each sits on a large piece of mahogany, in the design of an animal’s foot.

Dining Room

The Council Chamber

Going back downstairs you arrive at the Council Chamber. This was constructed as part of the 1820 extension and sits below the Large Ballroom. All the oak and mahogany woodwork is original. There’s seating for up to 160 people. At the front is a raised dais for the Lord Mayor, with the Deputy Lord Mayor and the Chief Executive on either side. There’s space for the press in front of them and public seating under the windows at the sides.

Council Chamber

In the corridor immediately outside the Chamber is a portrait of John Archer who was the first black mayor of London (or anywhere else in the country), becoming such in Battersea in 1913. He was born in Liverpool, the reason for his picture in the Town Hall. In the background is the Goree Piazza, a group of warehouses that used to sit in what is now The Strand, the road that runs parallel to the Mersey at the Pierhead. The Goree is an island off Senegal where slaves were taken before boarding ships to America.

Hall of Remembrance

The Hall of Remembrance only lists the names of those who were killed in the First World War – there’s no similar memorial for those who died in WWII. The 13,245 names are listed alphabetically on the finest parchment in the glass fronted cases around the room. The number of the dead is inscribed over one of the doors. Frank Salisbury (‘one of the greatest society artists of his generation’) created the frescoes in the panels and they tell the story of one of the fallen, from birth to death. The room was opened in 1921. The cap badges of the different regiments they belonged to, with the battles in which they fought, decorate the walls.

Hall of Remembrance

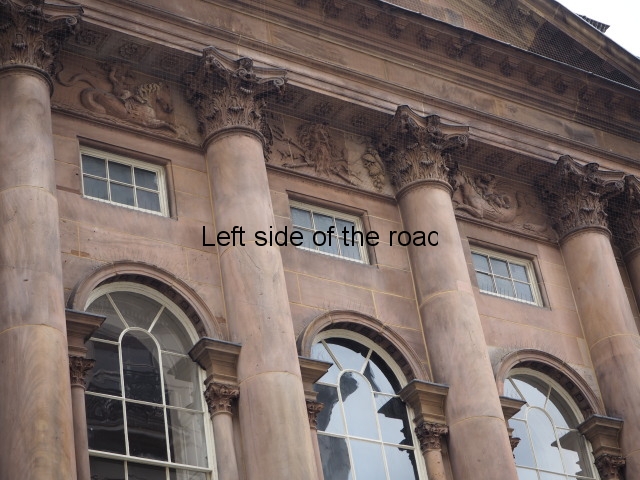

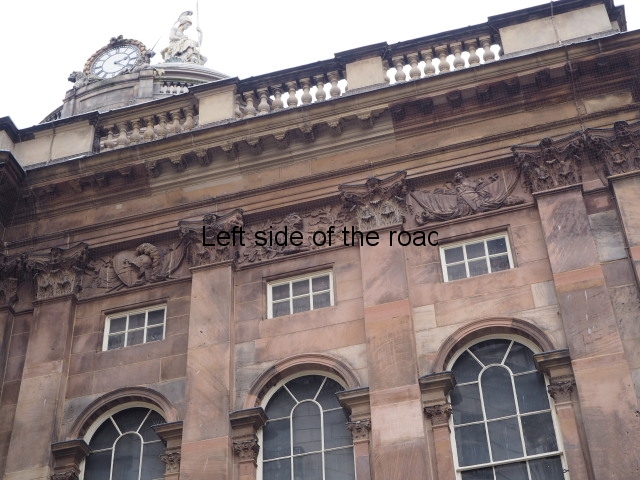

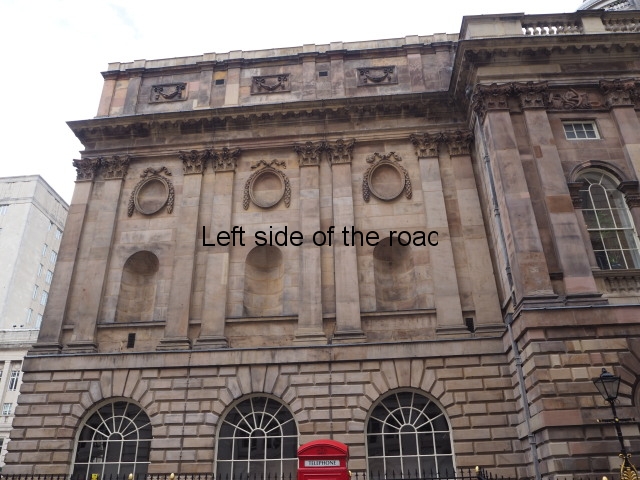

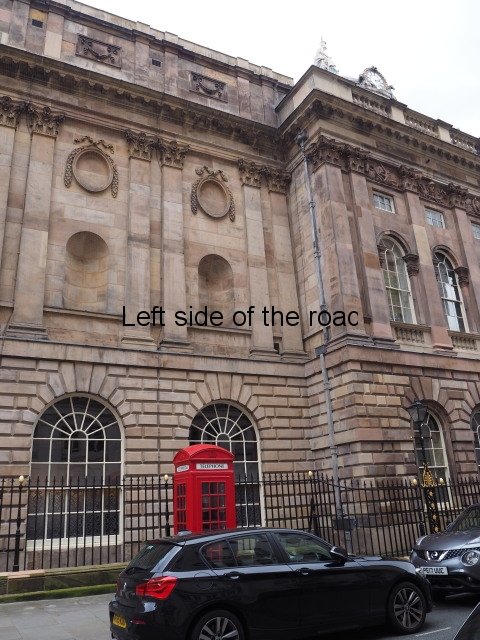

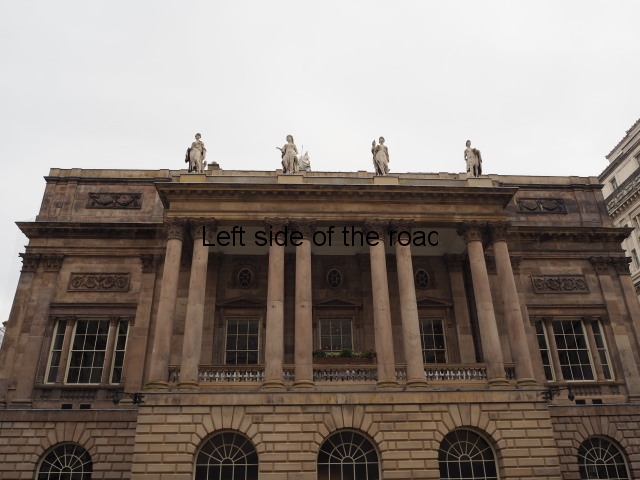

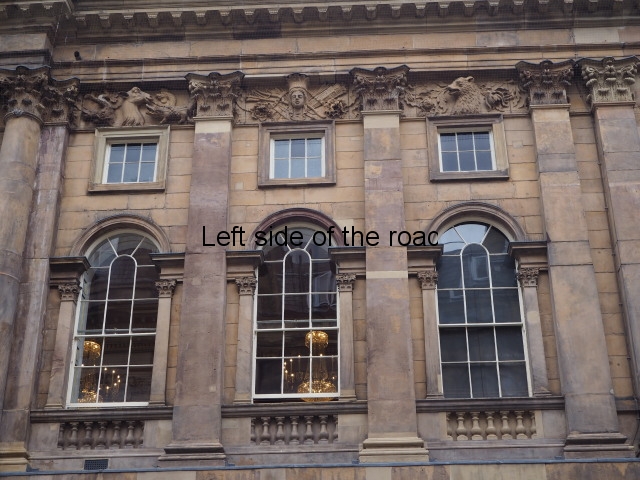

Exterior

On the occasion of the, what has now become the annual, open days at Liverpool Town hall attention tends to be placed on the ornate interior. However, all year round the exterior is free to view and tells a much more interesting and complex story. In effect, the exterior captures a snapshot of ideas, aspirations and attitudes of the rich and powerful in late 18th century Liverpool – encapsulated in this building in a manner unique in the city.

When the Town Hall was built at the end of the 18th century the slave trade was still legal (not being banned until 1807.) There are no direct references to the trade on the sides of the building BUT it is referenced by the very trade goods that came into Liverpool well into the 20th century. Cotton, sugar and tobacco, which were the mainstays of Liverpool trade for decades, were all produced using slave labour.

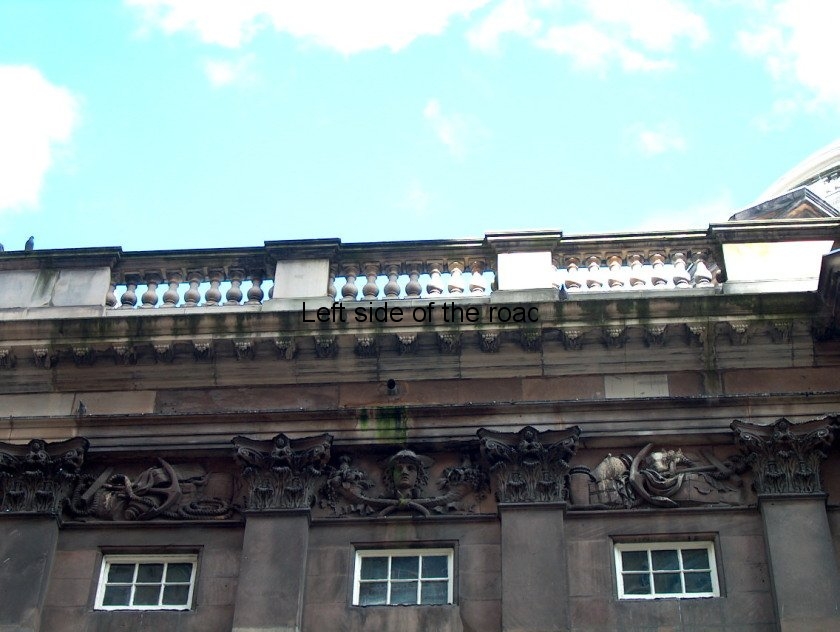

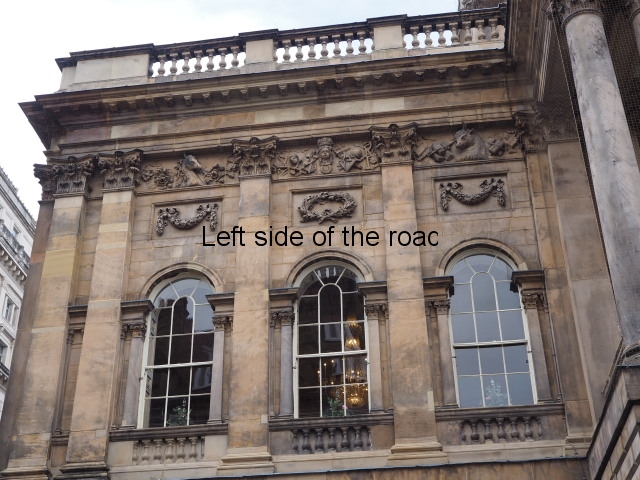

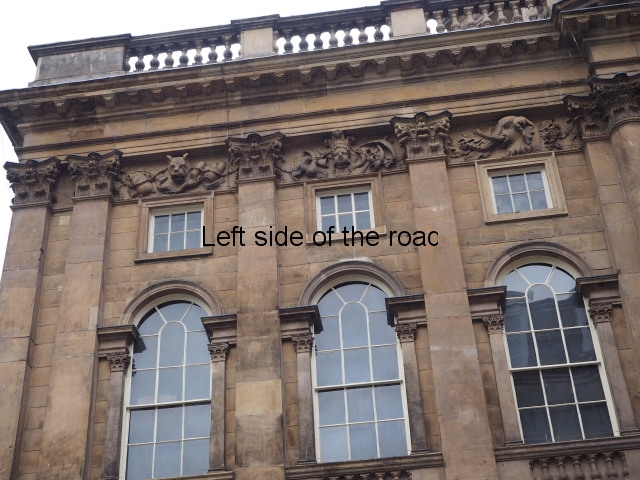

The friezes seem to be grouped together in some sort of theme, in threes, in the nine remaining bays (I assume that this arrangement would have continued on the north side but that would have been destroyed when the extension was constructed in 1820. However, one of the existing bays, that which now contains the balcony at the front of the building and over the main entrance, is obscured from view from the street – but can be seen from the edge of the balcony once inside the building.

The friezes are described in an anti-clockwise direction from the north-west corner of the original building, around to the front (south) side and then back along the east. According to financial records of the time the carvings were the work of Thomas Johnson, William Mercer and Edward Rigby (of whom I have no further information).

Trade

Anchor, cotton bales, tobacco barrels

1

A large ship’s anchor, to which is attached a very thick and ornate rope. This rope entwines itself around the rest of the items. The crown (the pointed end) faces towards the centre of the triptych.

A couple of bales of cotton – Liverpool was, and still is, the centre of Britain’s Cotton Exchange, the world price of cotton still being established locally.

Two barrels, one on its side and one upright – as these were coming to Liverpool they probably contained tobacco. A hogshead barrel (48” x 30” at the ends) could hold 1,000 – 1,500 lbs of tobacco. The tobacco was cured (dried) and prized (packed tightly into barrels) ready for shipment to England.

(Although now demolished British American Tobacco had a major factory on Commercial Road, in Kirkdale. It had access to the Leeds-Liverpool Canal at the rear. The site is now the location of a housing development called Tobacco Wharf. To show the symbiotic development of industry in the 19th century just a short distance away, almost a neighbour, was Tillotson’s Printing works. A major contract was the production of cigarette packets. Both places were closed down by 1984.)

A large pottery jar on its side. This could well have contained various spices from either the Americas or Asia.

A sail cloth is draped (artistically) over some of the items.

(The coil of rope on the right hand side is a different colour and looks like it has been subject to a level of repair and restoration at some time in the past.)

Mercury and cornucopias with grapes, pineapples and pomegranates

2

In the centre is the head of the Roman god Mercury, with wings on either side of his helmet. His hair spills out from underneath his helmet in long, curly tresses. Although he is now considered more to be the god of communication he was originally the god of financial gain and commerce – which fits more logically in this context. Mercury was also the god of thieves, so he has another fine fit when it comes to merchants.

Two large cornucopia radiate from just below his chin on either side. They are tied together with a knot of ribbon where they meet. These are symbols of plenty – but this was the plenty for a few.

On the left hand side we have: grapes (the vine twisting as it grows downwards), a pomegranate, cereal grains, a pineapple and another plant I can’t identify.

On the right the image is similar but with slight differences. Here there are also grapes, another pineapple (tucked away at the back at the top), cereal grains and what could possible be a large lemon. There’s the repeat of the same unidentified plant as on the left. The inclusion of those fruits that were only produced in tropical and hot climes (or under expensive hothouse cultivation in Britain) is a statement of how important Liverpool had become, the centre of this trading universe. And we should always remember that these images were created in the late 18th century so quite early in the industrial development of Britain.

Adding to the ornamentation are two ribbons, with tassels at the end, that twist and turn in folds creating a partial frame for the images above.

Anchor, spice jars, roll of silk and trunk

3

An anchor with the crown pointing towards Mercury. An ornate rope is shown passing through the eye and then entwining the collection of goods providing an idea of unity, all being together. This rope is not as long as the first in this group as this scene is much more crowded.

The shank of the anchor rests on a large, passenger trunk. Here we have transport rather than trade being represented (and Mercury was also the god of travellers). A sail cloth is draped over the shank of the anchor and covers the top of the trunk. This references the shipping upon which all this trade and communication depends. Shipping is alluded to on these friezes but there’s not one image of an actual ship in the existing 27 friezes.

A bale of cotton lies on the ground close to the crown of the anchor. At the extreme left of the image a large spice jar stands upright on its base and another lies on its side on top of the cotton bale.

Another large cotton bale lies on top of the trunk and, finally, on the extreme right, on the ground, is what looks like a roll of woven silk.

Although the majority of trade with Liverpool would have been with the Americas the inclusion of the silk also references trade with Asia.

The image is chaotic but would represent the situation on the docks where all these goods (known as break bulk cargo) would have been piled high waiting for transport to nearby warehouses.

There are also signs on this frieze that a repair has been carries out in the past, especially on part of the anchor close to the crown.

The Sea

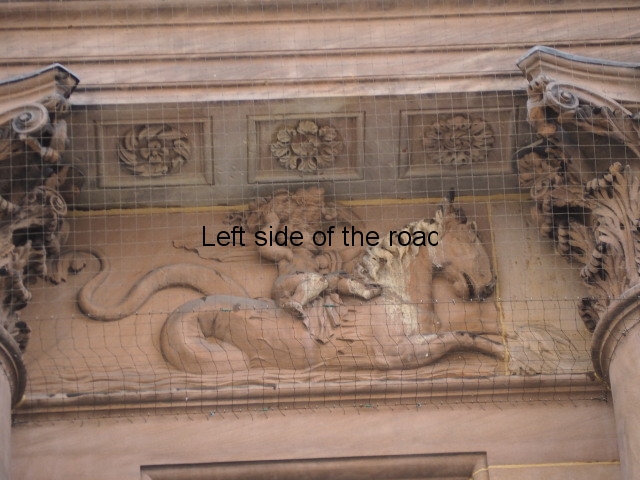

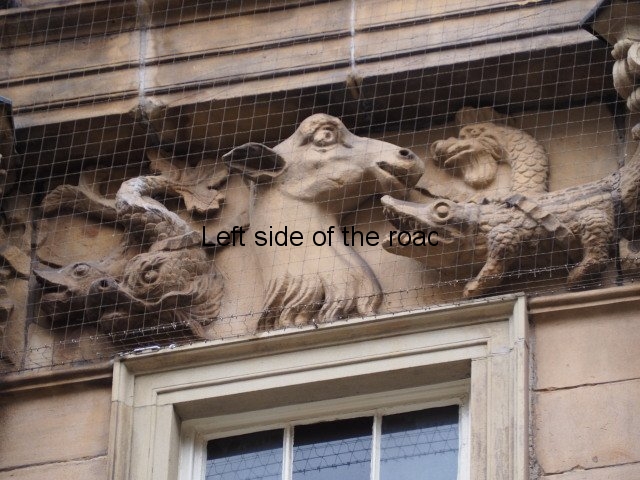

Hippocampus and putto

4

The first panel in this triptych is dominated by a large hippocampus – the mythological sea-horse from as far back in antiquity to the Phoenicians in the 4th century BCE. The myth was taken up by the Greeks and Romans. The relief here looks very similar to one that’s depicted in a mosaic in one of the Roman baths in the city of Bath. That can’t be just a coincidence as the architect (John Wood) of the Town Hall that was begun in 1749 was a resident of Bath.

It also provides us with the first example in Liverpool of the pretensions that dominated the ruling class from the end of the 18th century onwards. There are more indications of that pretension on this building (to be described later) and they were to resurface with a vengeance in the design of St George’s Hall almost a century later.

As Britain became more powerful, and other imperialist pretenders fell by the wayside, the British ruling class looked to the past to draw their ‘inspiration’. And in their minds the greatest empire that had ever existed, before that of the British, was the Roman and the merchant and later the industrial, classes appropriated images from that period to legitimise their own rule.

So here we have an early example of that appropriation, the ‘sea-horse’ having the fore legs of a horse but the rear legs merge together and become more like a fishes tail – as is the case with a mermaid. Here the hoofs are webbed and the tail is huge, curling back on itself and then flowing a long way behind.

The classical idea is perpetuated by the rider – a naked child, or putto – who sits side-saddle as the horse ploughs through the water. A cloak acts as a sort of saddle and it then passes over his right upper arm to fly out behind the racing pair. With his left hand he keeps one half of the shell of a giant clam on his head. This shell is full of the ‘fruits of the sea’ such as mussels, clams, a huge spiral (dog) whelk, a conch and what could well be a string of pearls.

Beneath the belly of the horse there’s a representation of the waves of the sea.

The pair are going from left to right, in the direction of the central panel.

There’s an indication of some repair work to the webbed hooves of the horse.

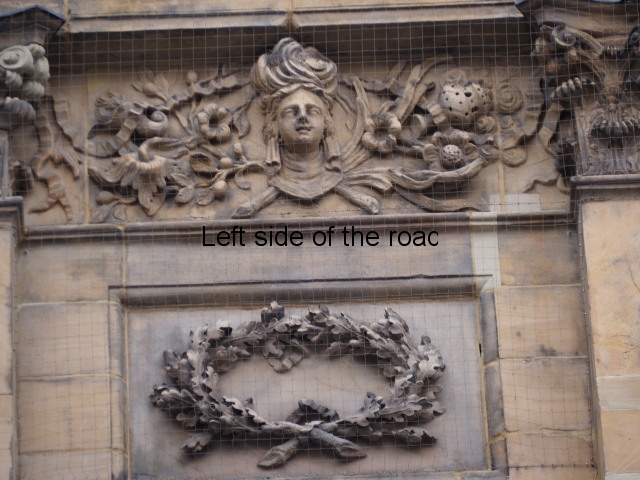

Neptune with trident and oar, together with sea shells

5

The next, and central panel of this triptych, is dominated by the head of Neptune, the Roman god of freshwater and the sea. He has very long and straggly hair as well as a long moustache and beard.

Below his head, hidden by his beard, his trident and oar cross each other, a ribbon loosely holding them together.

On the left hand side there’s a collection of sea shells: a conch, a large clam, a huge whelk, various clams and what looks like mussels on a string of seaweed.

The same collection is depicted on the right hand side. Virtually the same shells but in a different combination and arrangement.

Hippocampus, putto and dolphin

6

The third panel has another hippocampus and putto pairing. This time they are racing through the water from right to left. The putto sits side-saddle on his cloak which flies out towards the right. He is blowing into a large conch shell, using it as a horn.

The sea is again under the belly of the horse and this panel has the addition of a large fish in the bottom right hand corner. It doesn’t look very much like one but dolphins were often shown with the hippocampus in Roman imagery so the artist has chosen to copy the style of the dolphin on Roman mosaics which he might well have seen in Bath.

The Roman Empire

Helmet, shield, sword and standard

7

If Rome, through its mythology, had been alluded to in the previous two bays it comes in with a vengeance in the last bay on the west side. This Roman connection is definitely confirmed in the top left hand corner where, partially obscured by the decoration on the capital, is the eagle symbol at the end of the standard of a Roman infantry legion. Although there are no letters on this occasion the rectangular block at the feet of the eagle, during the time of the Roman Republic, would have been imprinted with the letters SPQR – Senatus Populusque Romanus, meaning ‘The Senate and People of Rome’. The letters remained even during the time of the Roman Emperors, with them usurping the consent of the Senate for their own ends. (As Liverpool’s wealth grew in the 19th century so did the aspirations of the ruling class and the letters SPQL – signifying the People and the Council of Liverpool) can be seen in the iron work of St George’s Hall.)

Attached to this block is a banner, edged with tassels, that covers the pole. Also from this point is the same sort of flowing ribbon seen on some of the previous panels. Just above and beside the standard is a ceremonial pilium (spear) which has a knotted, silk decoration tied to the staff under the blade. The two shafts disappear behind the central collection of armaments, the ends appearing at the bottom left hand centre of the panel.

The central position is taken up with part of the ceremonial dress of a Roman Legionnaire. Here we see a helmet with a chin strap and a neck guard. Attached to the top is a huge semi-circle of a crest of plumes of feathers. This helmet sits next to a circular shield, a scutum, used during the time of the Roman Republic, and attached to this shield, by a wide ribbon, is the gladius hispaniensis (Spanish sword), the short sword known by everyone who has ever seen a gladiator film. This has what looks like an eagle’s head as the top of the hilt (handle).

On the right hand side is another pilim, with the bunched silk decoration beneath the blade and another standard, this time more like a flag with tassels hanging down from just below the finial.

Lion and oak branches

8

The next panel is one of the least complicated. Here we have a lion lying down with its head raised and turned so that it is looking over its left shoulder – this is known as ‘lion couchant’ in heraldry. Both his front paws rest on two large, oak tree branches which bend and rise on either side of his body with the leaves meeting just behind his head.

The oak leaves are another borrowing from the Roman Empire as garlands of oak leaves were worn by Roman Emperors to symbolise power, loyalty and stability. The lion had been used as a symbol for individuals in various parts of Britain since the middle ages, in an attempt to show how fierce and brave they were in warfare. Here the image is probably to demonstrate the concept idea of strength as the concept of the lion as representing some idea of Britishness didn’t really enter popular culture until the middle of the 19th century.

Breastplate, sword, banners and ram’s head

9

From the relatively simple symbolism of the central panel we now go back to a complex telling of the story. There are a number of elements here I don’t understand.

But starting from what does seem to be clear and that’s the Roman armour in the centre of the panel. This would complement the other items depicted in the first panel so we now have a full suit of ceremonial armour. Here there’s a the muscle cuirass – breastplate (a type of body armour made from hammered bronze plate to fit the wearer’s torso and designed to mimic an idealized human physique). To this is attached a pteruges (a skirt of leather strips worn around the waist to protect the upper legs).

Attached to the breastplate, by a balteus (a cloth belt), is a short Roman sword. This looks like a ceremonial belt as there are tassels on the tied end.

With the ends of the poles crossing behind the armour are two, large banners, with many folds and two long cloth tassels hanging down from the top before the finials.

Parallel and above the banners, on both sides, is a fasces, the symbol of a Roman magistrates power and jurisdiction. These are basically a bundle of sticks so their value is minimal but depend for their power on the respect given to the holder. The fasces on the left is the basic model whilst the one on the right has a single-headed axe tucked into the middle of the bunch. Originally this addition indicated that the magistrates power included that of capital punishment.

The fasces was used as their symbol by the Italian Fascist in the 1920s and this is where we get the word fascist.

It’s now that matters get complicated and I don’t really understand what story is being told. On the top left of the breastplate there’s a lion’s head, facing out, with its toothless mouth, wide open. Almost eating the fasces on the left with the axe is another wide-mouthed lion’s head, but this time in profile. To the left of the first lion there’s what looks like the end of a trumpet (as seen in so many Roman epic films) so it’s possible that these are other types of instruments.

Finally there are two objects which appear to be on the ends of poles that run parallel with those poles of the banners, but with the carvings low down, as if they had been thrown down and not in a place of respect. On the left is a large ram’s head and on the right something that looks like a large, nobbly club head. Following the Roman connection the ram’s head could be a symbol of Pan and pagan religion – the fact that it’s lying on the ground symbolising the defeat of paganism and the victory of Christianity. However, the image on the right, also lying on the ground has beaten me.

So virtually all the images on this west side of the building have some sort of reference to the Roman past, be it Roman mythology or Roman military history. I would also say that the three triptychs were created by the same sculptor. This is reinforced by: the common, Roman, theme; the similarity in the narrow folded ribbons that appear in all three stories, especially the tassels at the end; and the similarity in the folds of the banners or sail cloths. He also had knowledge of Roman history and was familiar with the way the Romans depicted their life so he was more than likely someone who came from the city of Bath, probably coming to Liverpool at the same time John Wood, senior or junior, came to oversee the construction work.

Your guess is as good as mine

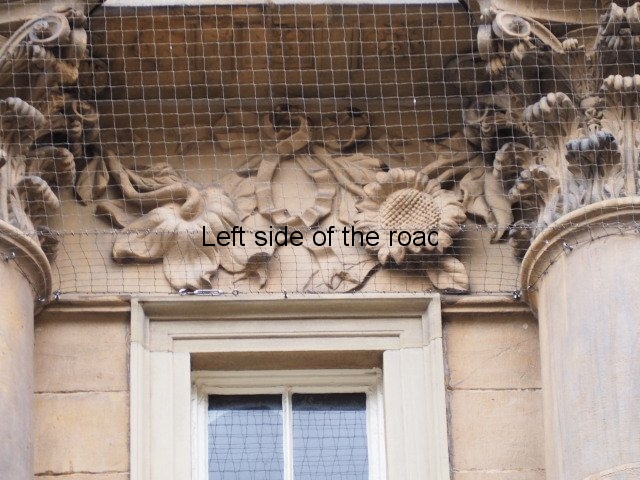

Horse’s head, flowers and plants

10

The first panel on, what is now, the front facade is in a completely different style. Here we have the head of a horse but this is a frivolous horse, not a sturdy working or fighting animal. It’s almost smiling, with its mouth partly open. The mane is curly and all over the place, as if it has just been running in a field for its own amusement. This sculpture gives no clues to why it is here or why it should occupy such an important position.

The head is in the centre of the panel and on either side are various exotic flowers but having little botanical skills can’t even make an educated guess at why they are here.

Charlotte, navigational equipment, artists’ and sculptors’ tools

11

If the previous panel is difficult to understand due to the lack of many clues the central panel in this bay is difficult to understand due to the abundance of items. There are many clues but the very fact they are together causes confusion.

In the centre is a female head upon whose head is a large crown. The female head becomes important in the rest of the bays on the south and east sides of the building, there being one in five of the bays and two in the sixth (inside the portico over the main entrance). So there’s a radical move away from the theme that was established on the west side where the influence came from Roman history and mythology.

Here, the young female head is sporting a very large, and British looking, crown. In fact it looks remarkably like the Crown of Mary of Modena which was made for the coronation of 1685. This later became the standard crown for consorts to the British monarchy to this day (although I don’t think Philip Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg ever wore it in public). That would make the wearer Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz who married George Brunswick-Lüneburg (better known as ‘The Mad King’). She was painted as a young woman until the end of the 1780s and that would have been the image that the sculptor would have seen (she would have been in her mid forties at the time of the sculpture).

If that is correct then there’s a logical reason for all the items on either side of the bust.

On the right are instruments related to navigation and the sea. On the extreme right is a large (taking up the whole height of the panel) representation of a sextant – used to measure the angle between an astronomical object (the sun or the stars) and the horizon which is used, with the time the measurement is taken, to calculate the actual position on the face of the earth – crucial for effective offshore sailing.

To its left is a small globe of the earth, slightly tilted to the right. Covering the bottom end of the globe is a sea chart on top of which are a pair of dividers (used to calculate distance). Underneath the chart is a part folded telescope and what I surmise is the end of a parallel rule – again an instrument used in navigation. Running from just to the right of the crown and disappearing under the chart is a wooden stick with three cross pieces. Following the navigational theme I would think this is a cross-staff (sometimes referred to as Jacob’s staff) which became obsolete with the invention of the sextant. Slightly bemused why it should appear here. Finally there’s a compass under the chin of the female head.

On the left hand side the items are all related to the ‘plastic arts’ – in this case painting and sculpture. Things are slightly chaotic but working from right to left you can make out an artists palette, with three blobs of oil paint around the edge. Sticking up through the hole in the palette are brushes and, possibly a mahl stick (what a painter uses to keep his hand away from the wet paint). The ends of the brushes rest on the head of a large, wooden mallet. Seemingly keeping these items together is another pair of dividers, similar but not exactly the same as the pair used in navigation.

Beneath the palette is a sheet of paper but the top end pokes out and on this can be seen a sketch of a human head. At the top edge of the paper is a wooden, model human head. This would have been used by both painters and sculptors to get the proportions correct when they were creating their images. (The nose of the model has been broken off – the only real sign of damage so far.) Resting on the piece of paper is the handle of another, smaller wooden mallet. To the right of this mallet head are three, short poles. These could be the end of a couple of paint brushes (but they don’t follow the line of the ones on the palette) and the third could be the end of a chisel – it’s got a flattened end.

The model head rests on a couple of sculptor’s chisels, their ends showing at the bottom left of the panel. Finally there’s a large contraption on the extreme left. This is the height of the panel and has two side poles which meet at the top and create a triangle with a cross piece lower down. In the centre is a another pole which ends in a sharp point. I don’t know exactly what this is but in context I would assume it’s a drill used by sculptors. Resting on the top of this tool is a set square, again a sculptor’s aid.

Linking all this item are a couple of wide ribbons that intertwine with the items on both sides of the crowned head and link the artists and navigational instruments.

If the assumption that the crowned head is Charlotte then there is a logic in her being surrounded by these diverse tools. She was an amateur botanist and knowledge in this field was advancing in leaps and bounds as different plants were being brought back from naval voyages around the world and such journeys were only made possible with the development in the science of navigation. She was also a ‘patron of the arts’ and she herself sat for many portraits.

Bull’s head, cotton bales, boxes and cloth

12

The next panel has a marvellous bull’s head as its centrepiece. He has a fine pair of horns and the hair is curly on his forehead. His mouth is open but, unfortunately, this is another place where time has caused some damage as the lower jaw is missing. But even so the bull doesn’t look too fierce.

He has different imported goods on both sides on him. On the right, next to his neck, is a small pile of bales of cotton. To the right of these are a random number of rectangular boxes, tied with rope, but not giving any clues of their contents. To the left of the head are two more rectangular boxes on top of which is a barrel laying on its side, with the top end having a smaller diameter than the bottom. Next to the barrel, on the right, are two circular items but I can’t work out what they might be or what they might contain.

On the extreme left is a large bolt of cloth. This is a heavy weight material so it might be sailing cloth, making reference to the importance of the sea in the whole trade process. A single rope goes from one end of the panel to the other (in a similar manner to the ribbon on the previous panel).

What unites these three panels I can’t work out. There was some sort of unity on the previous bays – and in most of those to come – but here the images don’t seem to be unified in each panel let alone the bays.

To be continued

Location:

Liverpool Town Hall

High Street

Liverpool L2 4FW

(That’s the official address. High Street is the tiny street to the right of the Hall itself. The more recognised address would be at the junction of Castle Street/Water Street/Dale Street.)

GPS:

53.406964

-2.99 1347