Spring No. 6

More on the Republic of Georgia

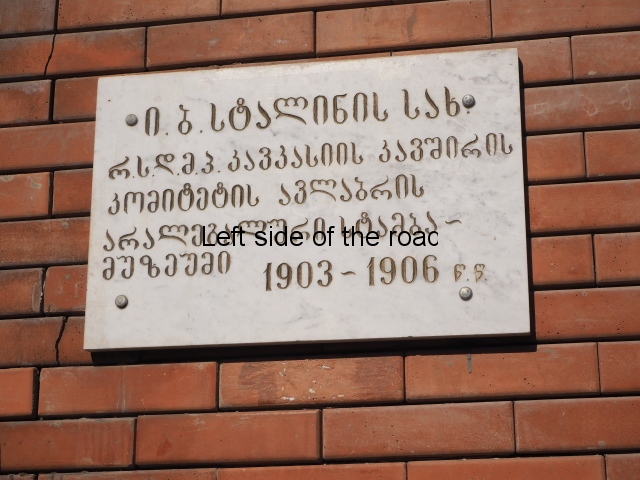

Joseph Stalin’s private bath house, Tskaltubo

Joseph Stalin, the General Secretary of Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, used to return to his home state of Georgia (in the Caucasus) to enjoy the benefits of the spa waters of the town of Tskaltubo – which was also a popular health resort for hundreds of thousands of Soviet workers and peasants – but if he was making this very long journey then surely he was returning to a site where he could enjoy the benefits on offer in the height of luxury, no?

Stalin wasn’t keen on air travel (from what I’ve been able to learn he only ever flew on two occasions, to the Tehran Conference and back in November/December 1943) and usually travelled by train – probably in a carriage similar to the one that is currently sitting outside the Stalin Museum in Gori. To make that journey to the spa town of Tskaltubo in western Georgia, therefore, was quite an investment in time and effort. Even today the journey takes at least two days and nights so there must have been something special awaiting him in Spring No 6 – the finest of all the spa buildings in the resort.

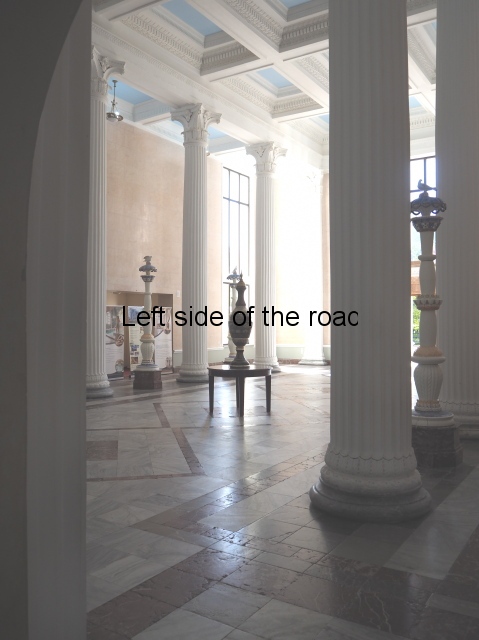

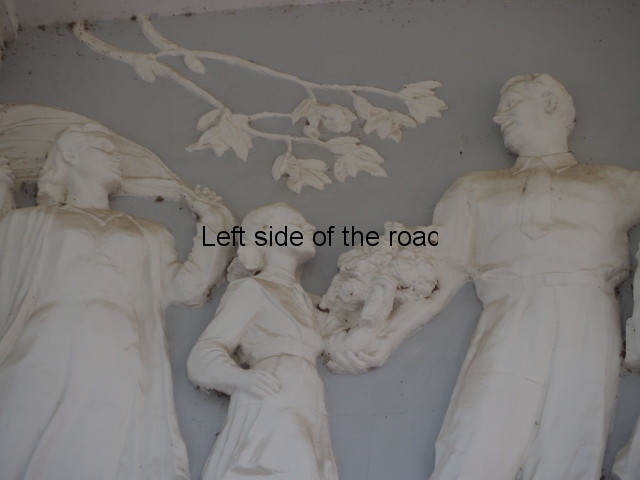

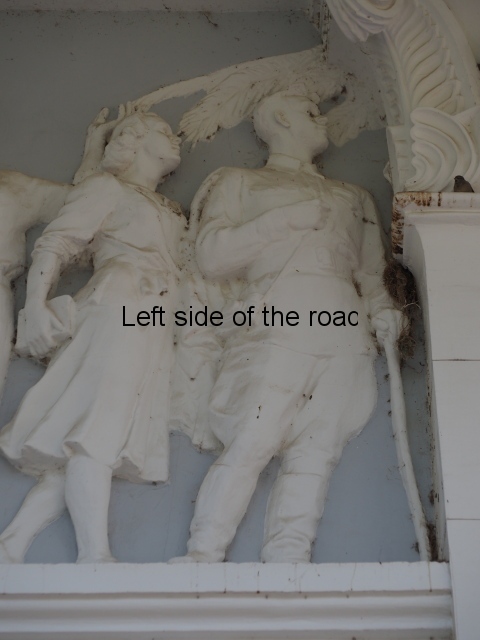

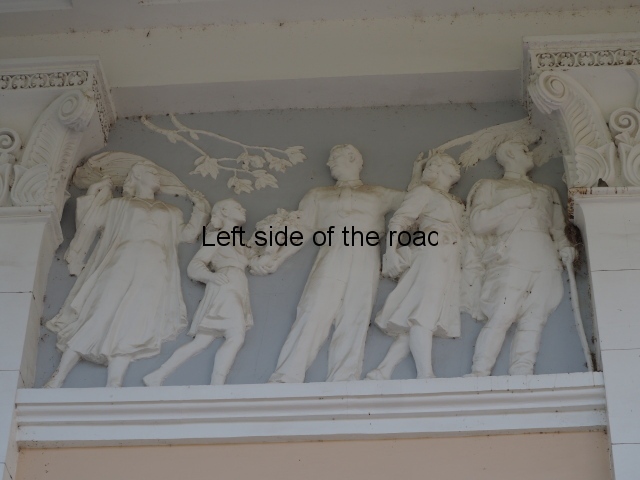

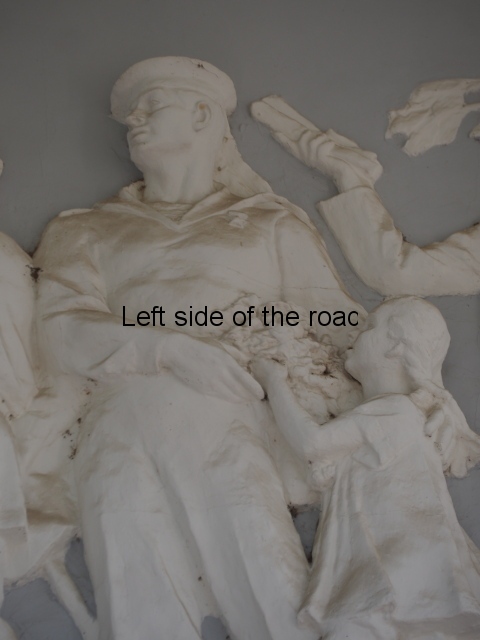

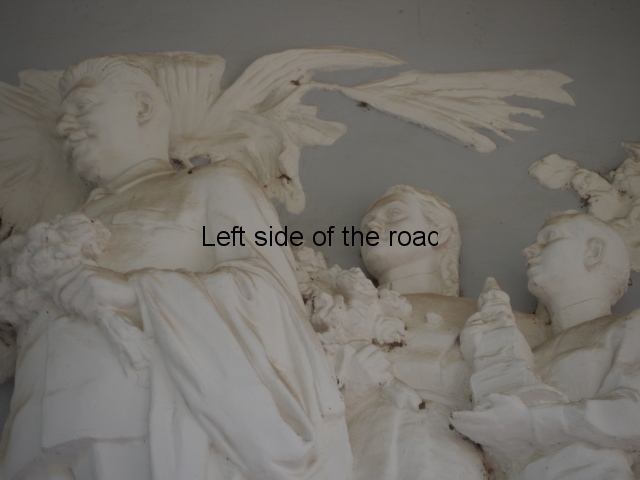

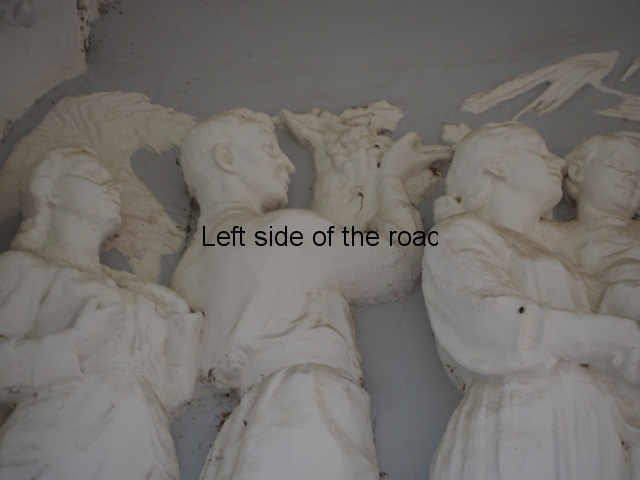

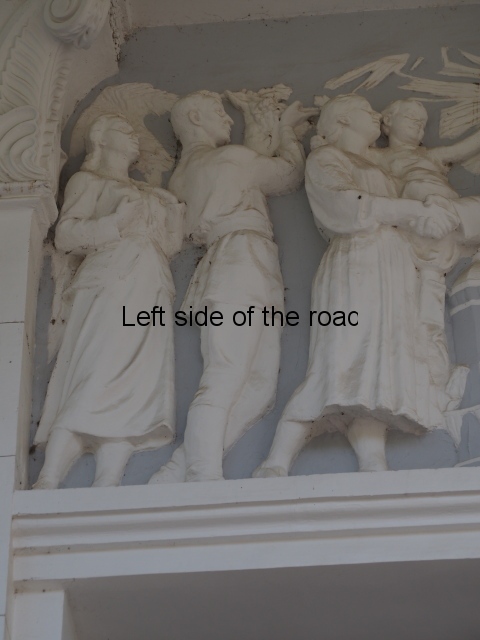

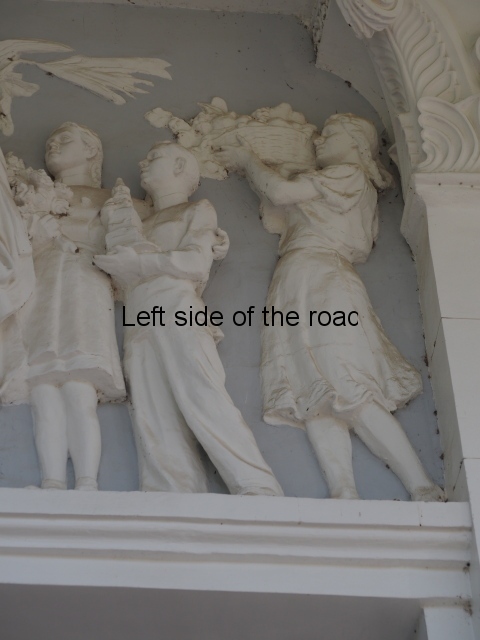

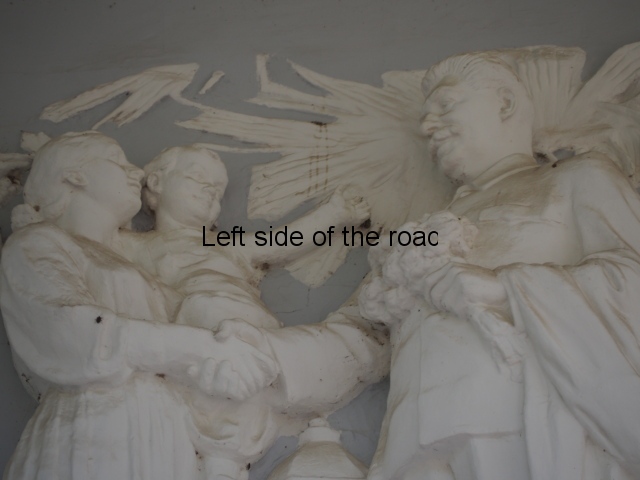

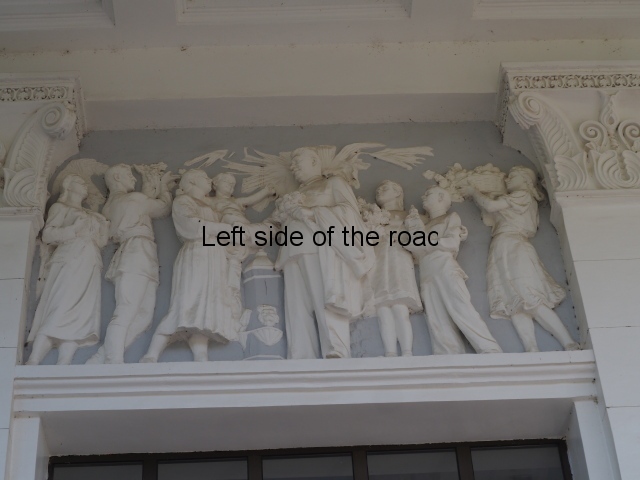

Spring No 6 is one of the few that are functioning in the town now. (Springs No 1 and No 3 are also functioning as of 2019 but they are much more modest structures.) However, the renovation of Spring No 6 has destroyed much of the original decoration from the time of its construction – apart from the main entrance portico and the entrance hall. In fact although very smart and clean the facilities that present day visitors use are somewhat sterile and lack any of the decoration I’ve seen in some of the ruined structures that are in and around Tskaltubo’s Central Park.

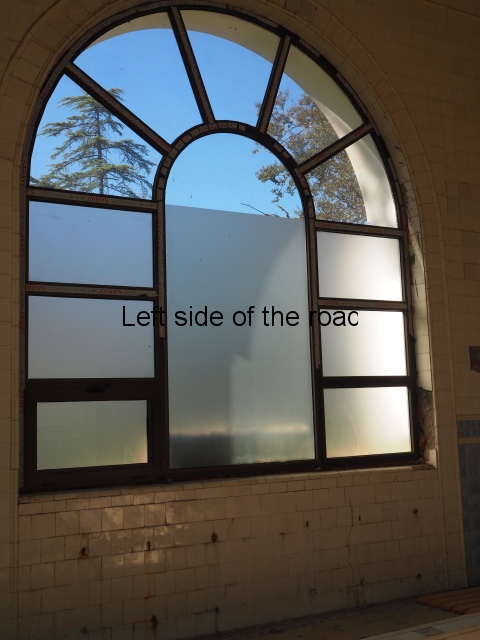

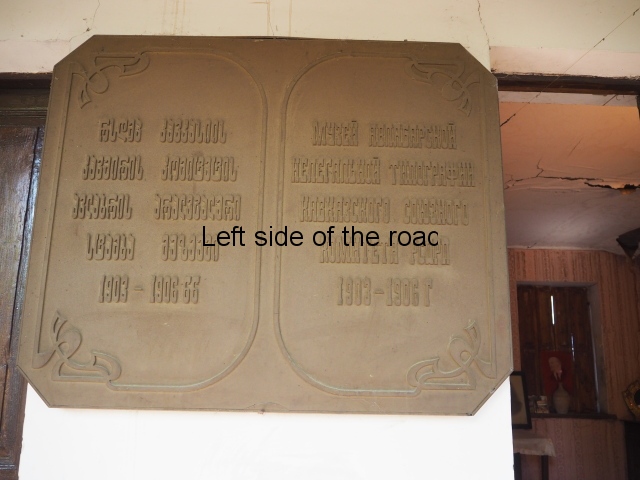

One area that has not undergone total renovation (there has been a replacement of the exterior windows as part of the general clean up of the building and also some work has begin on the ventilation system) is the room that I was directed to when I asked ‘Which was Stalin’s private bathhouse?’

I was directed to a woman who was sitting at a desk at the far end of the long, ground floor corridor that goes off to the right of the main entrance hall, running parallel to the frontage of the building. She had been asked to direct me to this special location.

It was with a feeling of suppressed excitement as I walked down the corridor. What was I going to see? What little hidden gem seen by relatively few people from western Europe (and many more from the east) was about to reveal itself to me? Surely the leader of the USSR, the country that had defeated the fascist Hitlerite beast only a few years before would be revelling in glory and have a private bathhouse rivalling those of the Roman Emperors?

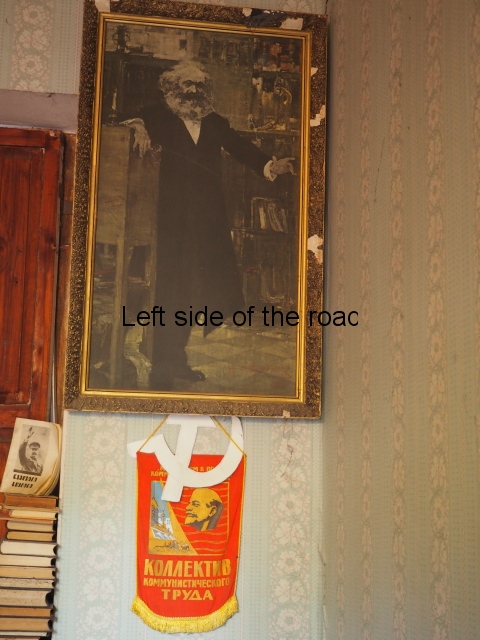

Stalin was a megalomaniac and monster (according to the fascists he defeated, the capitalists and imperialist whose rule and control of the life of billions of people he constantly challenged, and those trotskyites, revisionist and social democrats whose lying and duplicity he spent much of his life uncovering and crushing with the necessary force) so what I was about to enter would be a grand arena, decorated in a manner paying homage to the Generalissimo.

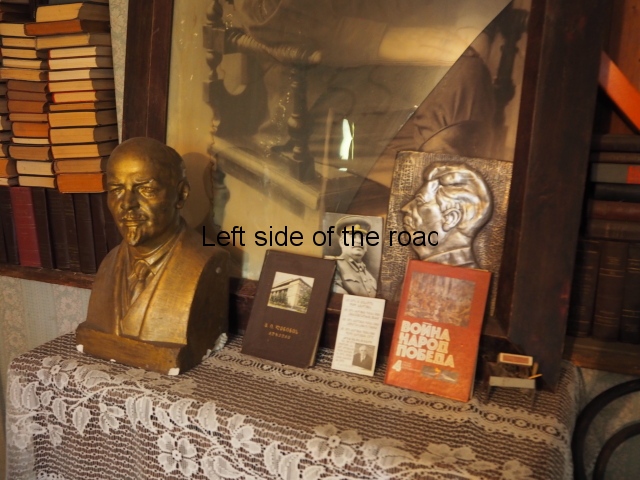

According to the fascists, imperialists, revisionists and other anti-Communists Stalin would have surrounded himself with memories of his past actions – such as the destruction of the traitors, splitters, wreckers, renegades and fifth-columnists in the Soviet Union, the the late 1930s, before the imminent war against Hitlerite Germany.

Surely in the tiles on the floors and the walls there would be the severed heads of those internal enemies; Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev and other Party members who sought to undermine the iron unity of the Marxist-Leninist Party and colluded with the enemies of the Soviet people; Tukhachevsky who saw the Red Army as just another, more modern, army of Tsarism; the kulaks who sabotaged production in the countryisde and did everything they could to prevent the transformation of the agricutural economy through collectivisation; and the external enemies, especially the Hitlerite fascists.

And I was really interested in what sort of desk would be located in the bath house. Every picture (photo or painting) I’ve ever seen of Joe sitting and writing at a desk has had the caption ‘Stalin signs yet another death warrant.’ This was even when closer analysis of the actual document said ‘Dear Mr Milkman, no milk today’. I have never seen a semi-naked Joe doing this but if he spent so much time in such activities then he wouldn’t have wanted to have wasted time when he was up to his chest in warm spa water. So a desk which could have held stacks of pre-printed death warrants, a bunch of pens and gallons of ink would have to have been part of the architects remit.

My heart started to beat faster as I approached the woman sitting at her table at the end of the corridor. She didn’t speak but indicated a door way just behind her, on her left. I walked the handful of metres to the door and realised it was an ante-room.

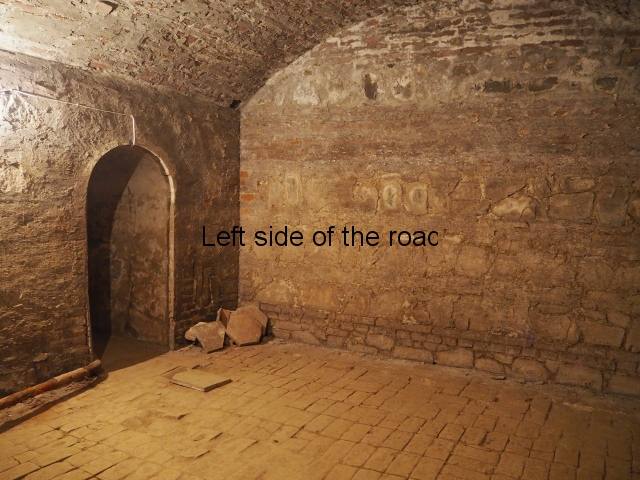

But what an ante-room. If was about twice the size of my bathroom – and I live in a modest flat. How could this room cope with the large entourage that would have accompanied Comrade Stalin on his journeys. There was a window to the outside, in one corner was a single leather covered armchair but apart from that the room was devoid of any decoration – but with a parquet floor in a fairly reasonably condition.

Entrance to Stalin’s private bath house

To the right another door led to a room with tiling on the walls and the floors. I took two steps to the door and had my first view of Comrade Stalin’s private bathhouse.

My first reaction was shock and surprise. I uttered a few words, I think audibly.

‘They’re taking the piss.’

In front of me was a tiny space – considering the size of the building. My first view was towards the corner of the room with two large windows at 90º to each other. I looked to my right thinking the main body of the room was there. All I saw was a tiled wall.

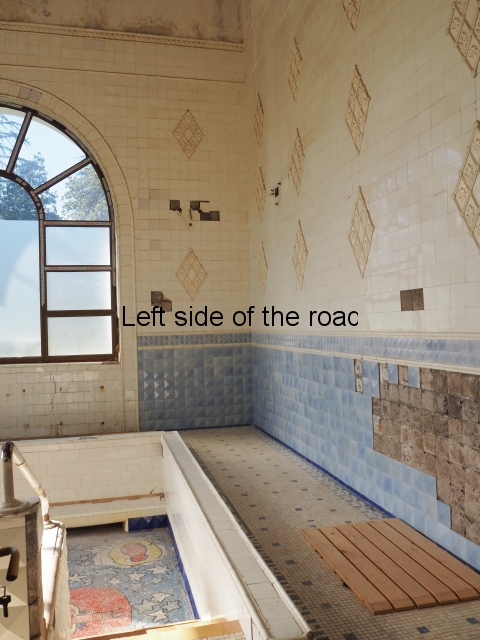

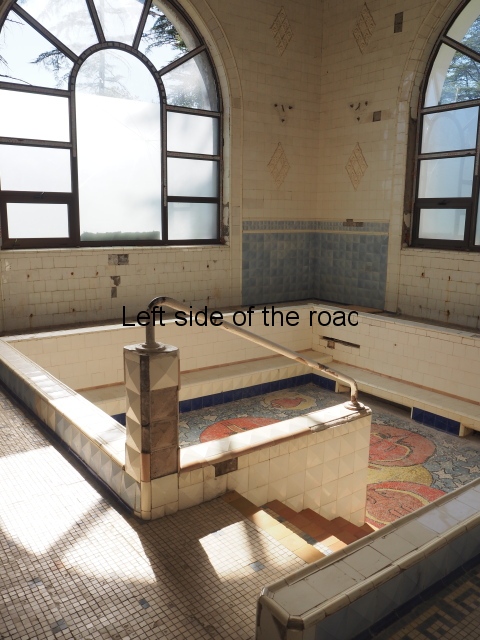

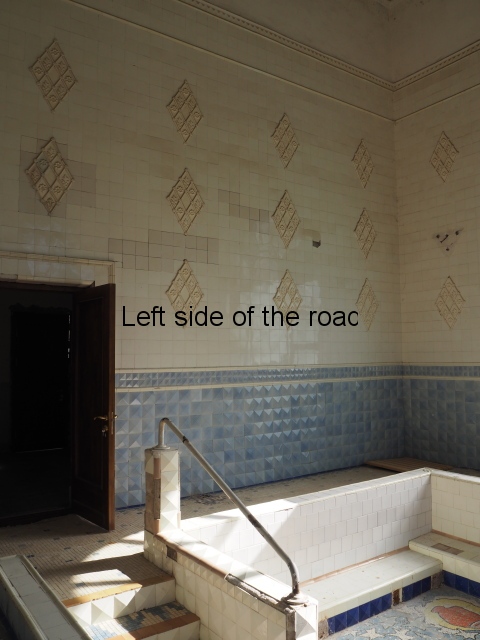

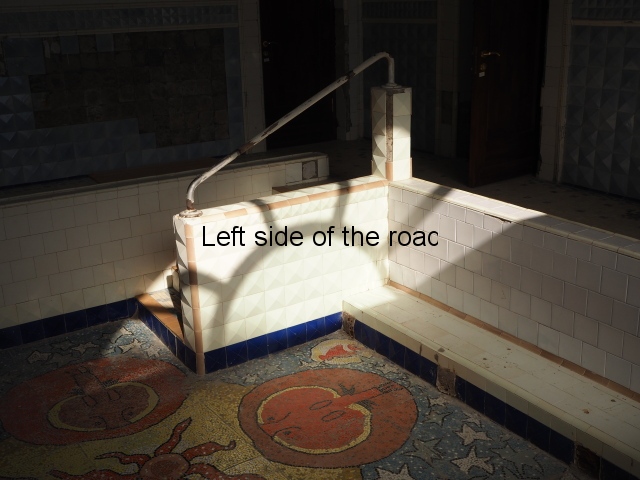

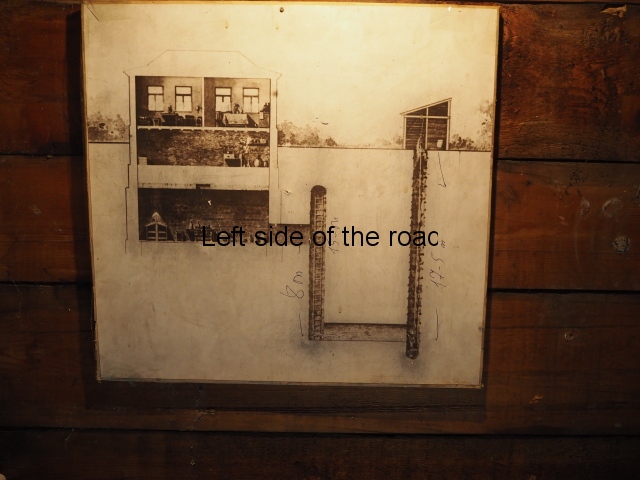

The room was about 6 metres square, with a high ceiling and with the walls covered in blue and cream ceramic tiles (some missing). There was some decoration on the walls but this was of a simple, geometric design. There was a walk way around the room which was covered in small square tiles that were set in simple geometric patterns, in places starting to come loose. In the centre of the room was a sunken bath, about 4 or so metres square. At one corner there were fours steps down to the pool with a tubular steel handrail on the left side. Around the edge of the pool were tiled covered concrete benches. There was no sign of a desk at all. But most shocking of all was the decoration at the bottom of the pool.

Stalin’s jelly fish

In place of the images I had expected there was a mosaic of cartoon like jelly fish – with anthropomorphic characteristics. Four of these giant jelly fish were half out of the water and seemed to be about to attack a very strange creature (possibly representing a crab but if so it’s missing a couple of legs) which is sitting on a round patch of sand. In the water are cartoon fish and a huge number of starfish.

There were signs of renovation of the space, which seemed to have stalled. The only new work that had been completed was the replacement of the large windows – this would have taken place so as not to spoil the look of the facade of the building from the park. If the present owners follow their past practice then the jelly fish will go – that would be a shame.

The knowledge then crept up on me. This wasn’t a room built especially for one of the greatest leaders of the working class of all time – this was a children’s paddling pool.

But it was also Uncle Joe’s private pool. He is recorded as having been there some time in 1951. The search is on for photographic evidence.

Just goes to show that you have to be careful what you wish for. You will almost always end up being disappointed.

Location

Spring No. 6 is in the northern part of Tskaltubo’s Central Park, about a ten minute walk from the present day market in the centre of town.

GPS

42.3223

42.5989

How to get to Tskaltubo

Marshrutka number 30 leaves from its terminus on the western side of the Red Bridge, which crosses the Rioni River beside the main Kutaisi market. Closer to the market is the stop for a number of buses but you walk through that area (passing a cheap out door bar on the right) to cross the red painted iron bridge. The marshrutka will be on the left once on the other side. They leave roughly every 20 minutes. Cost GEL 1.20 (not the GEL 2 as in some guide books – although some of the drivers will take the GEL 2 and say nothing although others are honest). The price will be on a piece of paper somewhere, normally at the front of the vehicle.

Journey takes about 30 minutes to get to the centre of Tskaltubo. Once you cross the railway track (after 20 or so minutes) you are at the bottom end of Central Park. The marshrutka then follows Rustaveli Street on the eastern edge of the park passing the railway station and information office, the Municipality, Court and Police buildings, and then the entrance to the huge (now luxury 5 star) Tskaltubo Spa Resort all on the right. (The marshrutka takes the same route when going back to Kutaisi and can just be flagged down anywhere along this road.)

When you get to the northern edge of the park the road widens out and after passing the Sports Palace on the left and the now being renovated (although seemed stalled to me) huge Shakhtar Sanatorium on the right the marshrutka heads up to the main market. Get off when the bus turns right at the corner by the ugly, modern Sataplia Hotel. This is where you would look for another marshrutka if you wanted to go to the Prometheus Cave.

To get to Central Park go back along Tseretseli Street (not the road you came up), pass the mural of the telecommunication workers on your left and head down to a very wide road junction. Cross this wide expanse of tarmac towards an arch and at the open space at the top end of the park head south and pass by the right hand side of Spring No. 3. Continue south until you reach the white, side wall of Spring No. 6. The entrance is on the west side of the building.

Alternatively (if arriving by marshrutka) you could get off at the main entrance to the Tskaltubo Spa Resort and walk towards the back of Spring No. 6 through the park.

More on the Republic of Georgia