Ukraine – what you’re not told

Gjirokaster Martyrs’ Cemetery and the 75th Anniversary of Liberation

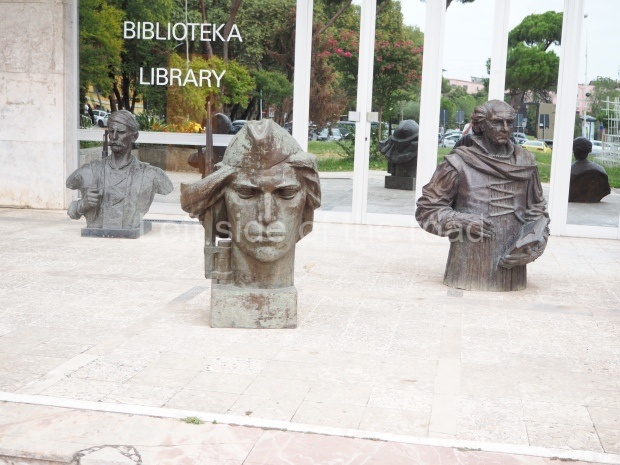

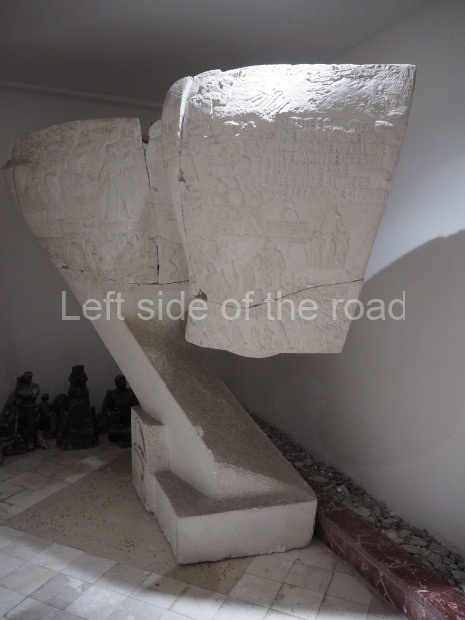

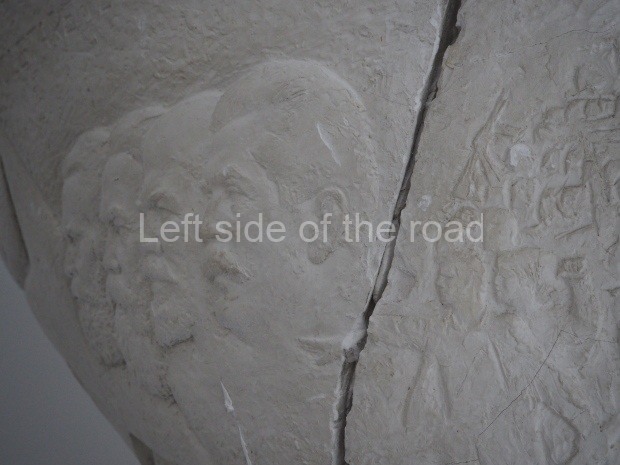

Details about the lapidar, and some of the history, of the Gjirokaster Martyrs’ Cemetery (ALS 376) were posted some time ago. However, on the occasion of the 75th Anniversary of the Liberation of Gjirokaster from the Nazi occupation I was fortunate enough to be, again, in the city.

The Nazi’s were forced from the city by the Partisans, under the leadership of the Albanian Communist Party (that was later renamed as the Party of Labour of Albania) on 18th September 1944. That date is still considered important, even through all the changes and the anarchy that hit Gjirokaster significantly during the 1990s, as the main street in the new town is still called Bulevard 18 Shtator (18th September Avenue).

On that date in 2019 a small celebration was organised both at the cemetery itself and in the theatre in the new part of town – but much less than it would have been during the period of Socialist construction. However, the event did follow certain aspects which were common of such occasions between 1944 and 1990.

There was a march from the centre of the new town to the cemetery (which is on the edge of town on the national road that heads towards Tepelene (and hence Tirana) in the north and the Greek border at Kakavija towards the south) where a short ceremony took place and this was followed a short time later by a cultural performance/speeches in the town’s theatre.

As I have said this was very low key, the rest of Gjirokaster carrying on life as normal, something which would not have happened in the past. Such an anniversary would have been a public holiday and the celebration would have been much more formal and with events taking place all over the town.

However, there are a few points I would like to emphasis from my observation on the day, which include how things were done in the past and how they were done in 2019.

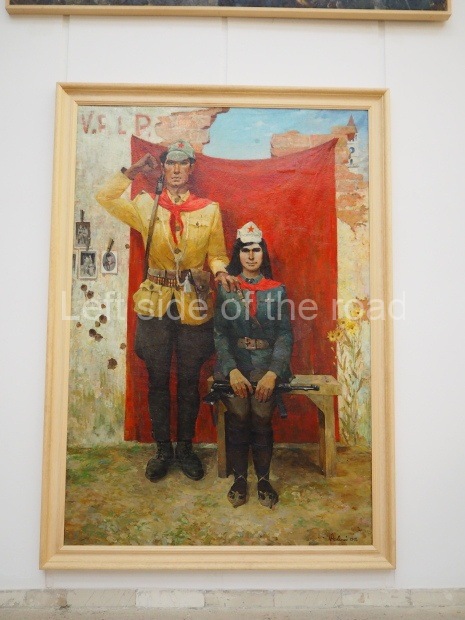

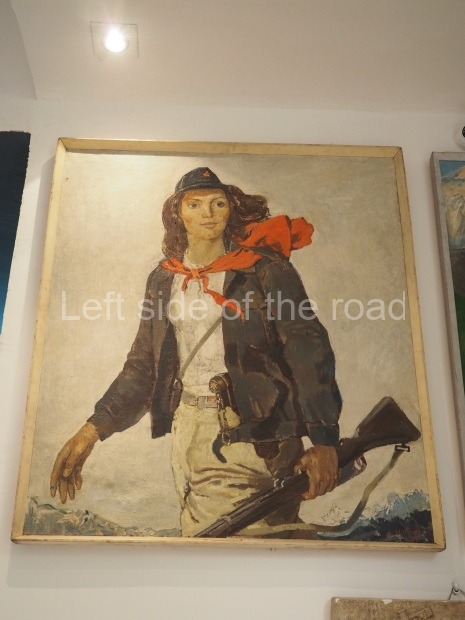

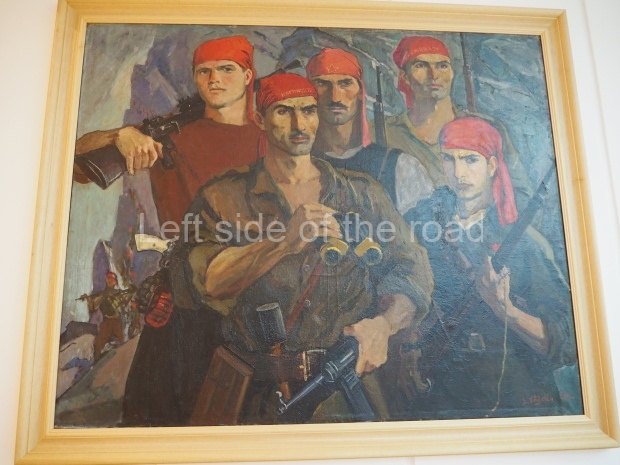

It was obvious that those who still identify themselves with the Socialist past in Albania were those who wore a red scarf around their necks. This was part of the ‘uniform’ of the Partisans. This I have pointed out in many descriptions of the lapidars which have appeared on the page under the heading of the Albanian Lapidar Survey.

The military presence existed but on a much reduced level – just really a couple of officers in regular, i.e., not dress, uniform. Whether it was seen as an obligation I can only surmise. During the Socialist period the military presence would have been in the form of the People’s Militia which consisted of both men and women.

The tradition at ceremonies in the Martyrs’ cemeteries always consisted of children from the Young Pioneers standing at each of the tombs and during the ceremony a single red carnation would be placed on each tomb. As time passed it would obviously mean that many of the martyrs would not have any surviving relatives who might be able to place flowers on the tombs. By having the Young Pioneers do so, in a formal and organised manner, it meant that none of the anti-Fascist fighters were forgotten and left out. In 2019 it was again young people who brought baskets of flowers and then placed a single flower on each tomb – but these were older children, in their teens, rather than the younger, primary school children, who would have carried out the task pre-1990. (But someone ‘forgot’ to count the tombs as at the end of the flower distribution there were still quite a number without a flower.)

There was very little ‘formality’ during the 75th Anniversary celebration at the cemetery. People tended to mill around rather than stand in any formal manner. If you want to draw comparisons then the fact that this is being written on 11th November provides an easy and almost direct comparison.

At 11.00 on Remembrance Sunday (in the United Kingdom) in the centre of London at the Cenotaph there will be a very formal presence of politicians and aristocracy. After the Minutes’ Silence there will be a very formal and organised laying of wreaths and then a march past of veterans. To do otherwise in Britain would cause an outcry of indignation from various sectors of the population and media. For people to just walk by and see who had left the wreath at the Cenotaph during the Minutes’ Silence would be considered disrespectful. That was virtually what was happening in Gjirokaster on 18th September 2019.

I’m not saying that is either good or bad. It’s just to remind readers that countries have various ways in commemorating their dead in past wars. It should also be remembered that, in theory if not really in ultimate practice, in the early 1940s the so-called ‘Allies’ were supposed to be fighting on the same side and that the defeat of Fascism was the aim of all the countries. So perhaps people should remember this when they start to make judgements on the past in Albania.

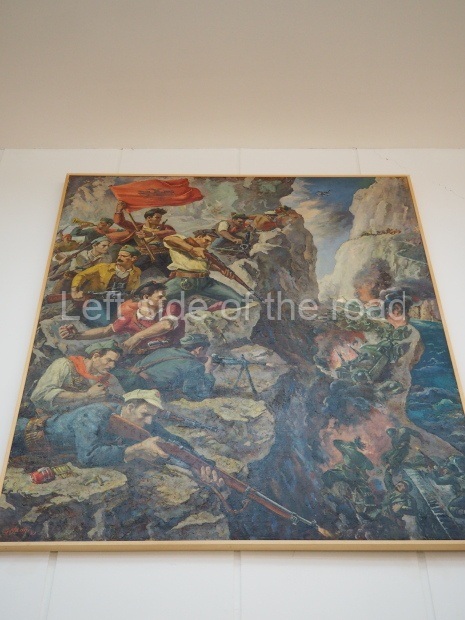

Without significant help from any other army of the major warring Allies the Albanian people were able to liberate themselves from both the Italian Fascist and German Nazi invaders. In some respects that was their greatest crime – at least in the eyes of the British and the Americans. It meant they weren’t beholding to any external power and would fight to maintain the independence they had gained on 29h November 1944. It was for this reason that the British threatened and made attempts at ‘regime change’ in Albania even before the sound of the cannon fire had disappeared in the distance.

But back to the ceremony on 18th September 2019.

One small event that caused a local stir was the presence of an older man who help a portrait of Comrade Enver Hoxha, in a glass frame, high above his head in front of the images of the eight heroes/heroines of Gjirokaster depicted on the lapidar. He drew the attention of the media present as well as a number of onlookers. Though a single incident it was good to see that the spirit of the past still exists within the city.

Hopefully, readers will be able to get an idea of the event from the pictures in the slide show below.

Event at the theatre

Much of the celebration that continued in the theatre an hour or so after the ceremony at the celebration went over my head as a non-Albanian speaker. However, it was possible to get the general tone in that the Liberation of the town from the Nazis 75 years previously was still an event that needed to be remembered and commemorated.

(This is despite the fact that in Tirana Park, in the capital, there’s a monument to the Nazi fallen – put there to please the so-called democrats of Germany and, no doubt, in a bid to curry favour with a principle player in the European Union – which Albania is desperate to join and which (even though it goes against all the logic of the EU Constitution). This is likely (bizarrely) to happen in the not too distant future. High level talks are taking place in 2021 – when the rest of the EU is starting to implode – and the only reason I can see for this is the huge mineral resources that have so far remained untapped in the (at the moment) relatively inaccessible part of the north east of the country. But how many other countries that fought the Fascists in the Second World War have monuments to the dead of the invaders?)

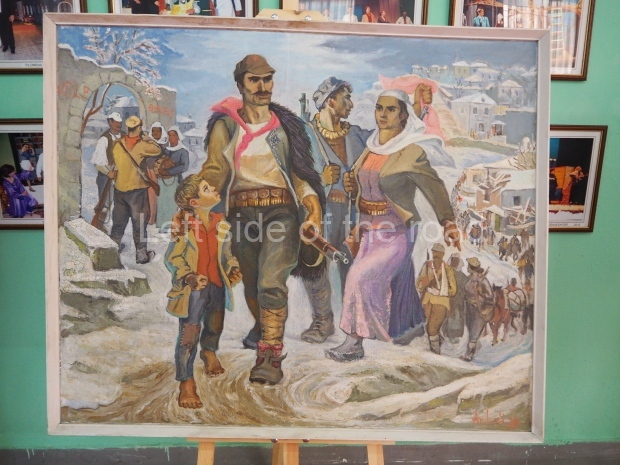

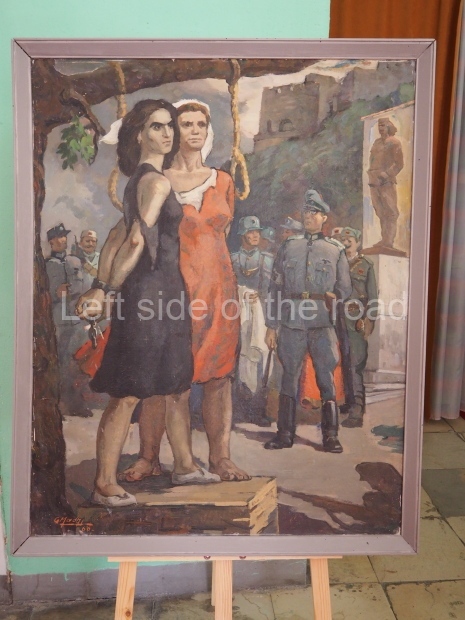

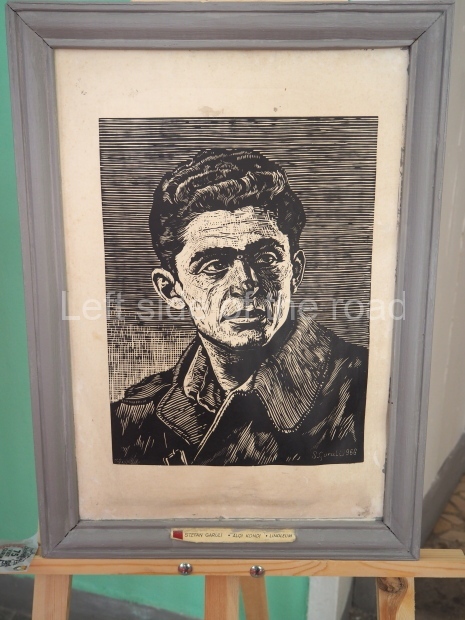

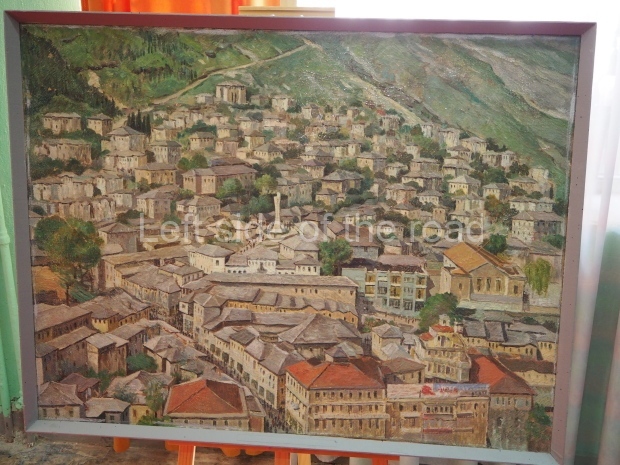

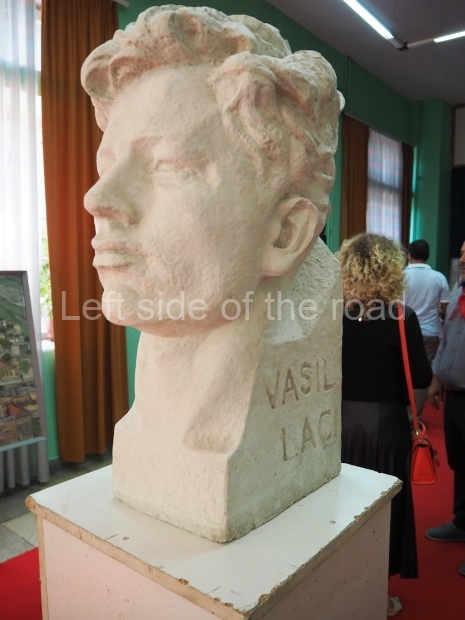

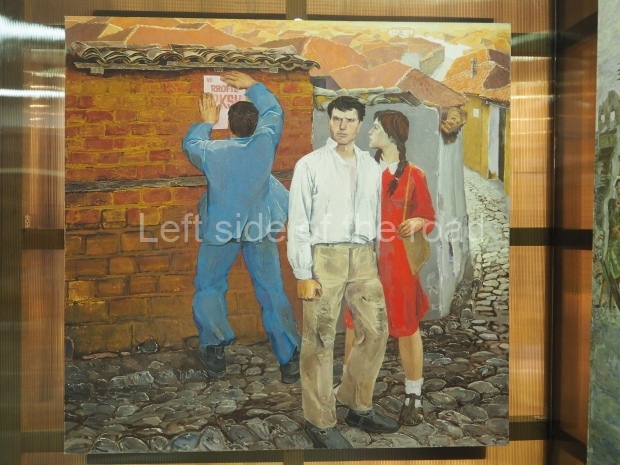

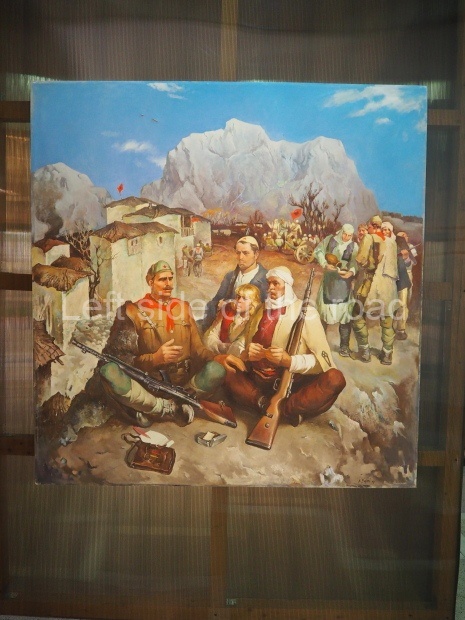

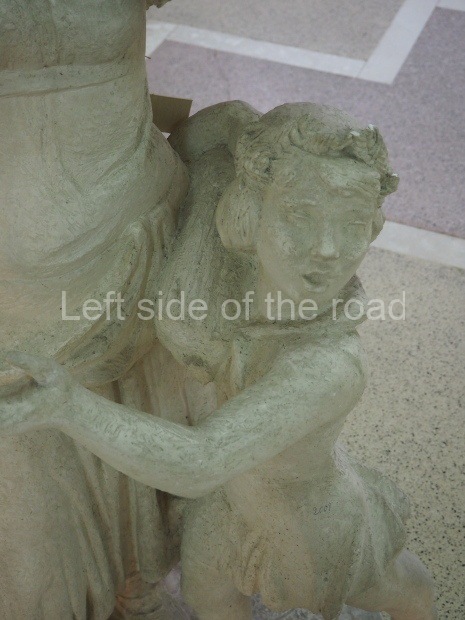

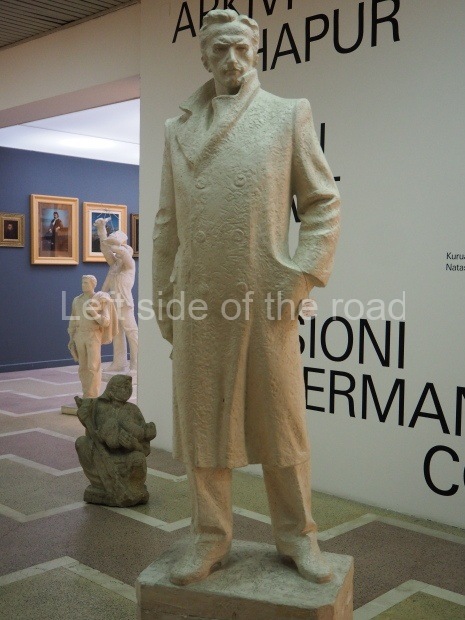

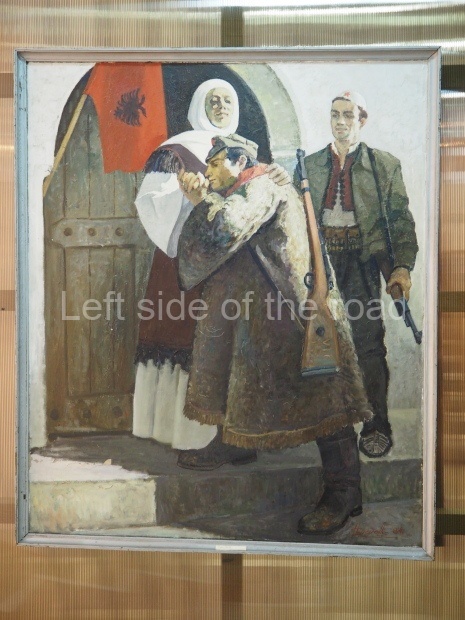

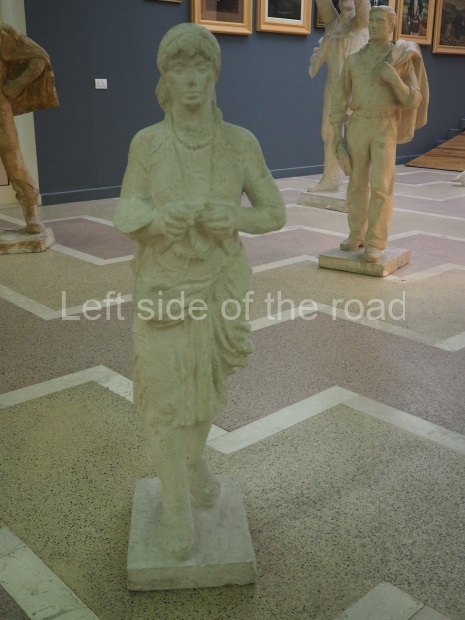

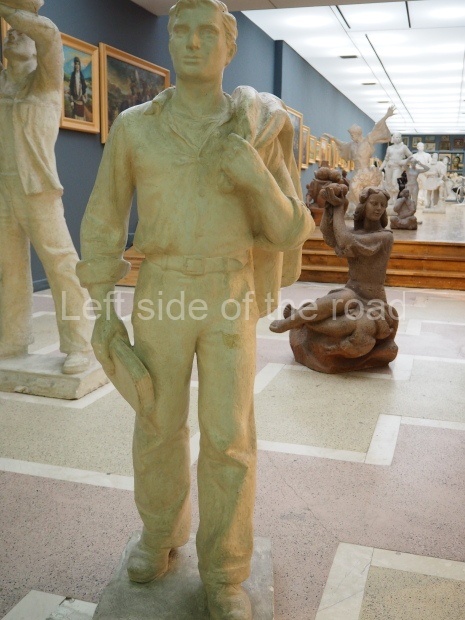

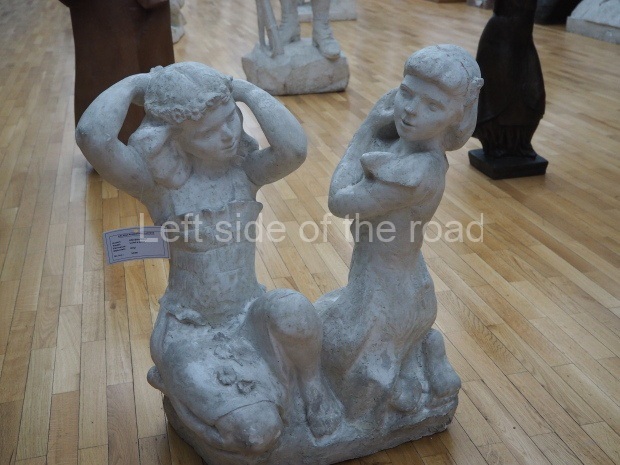

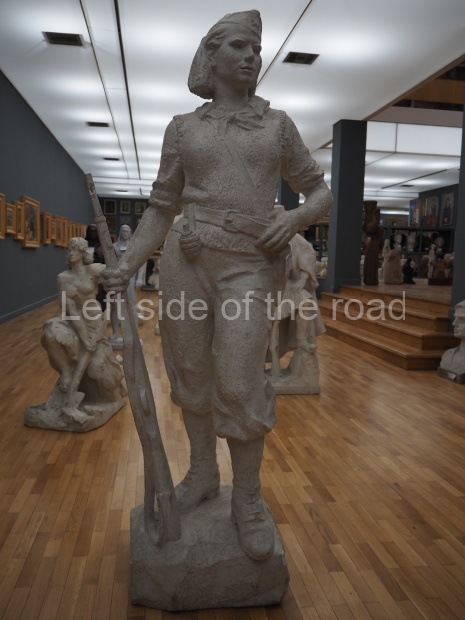

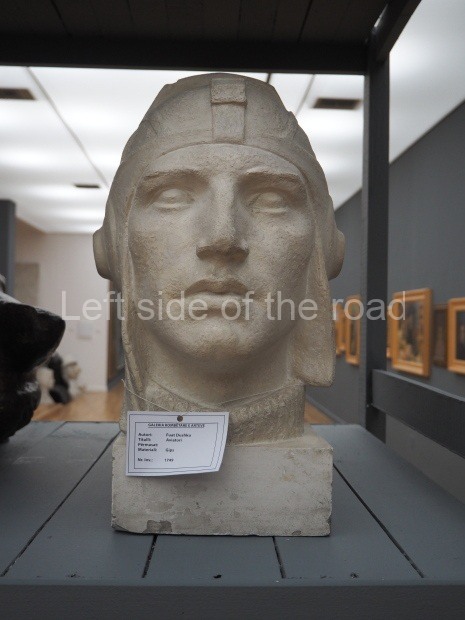

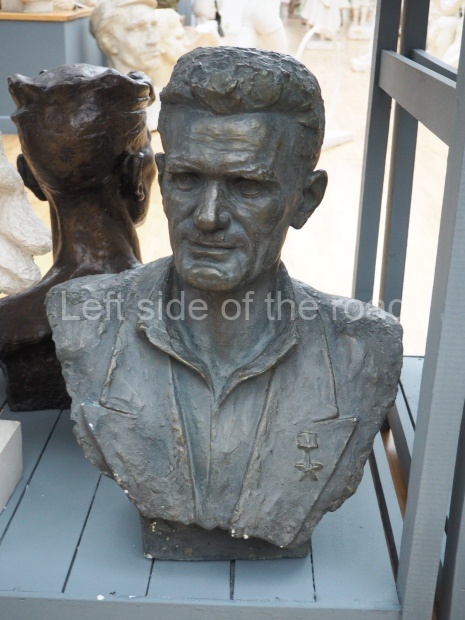

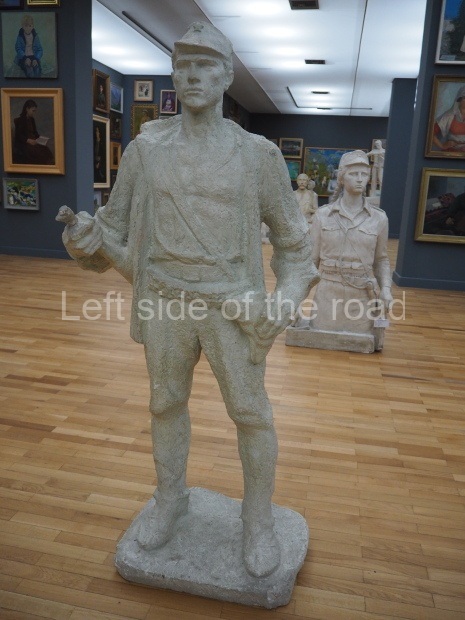

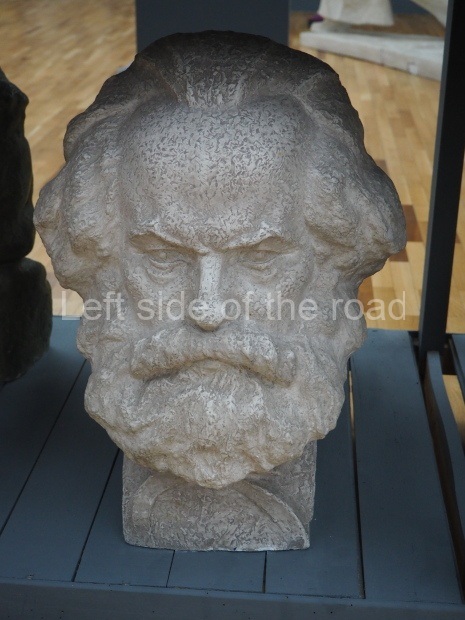

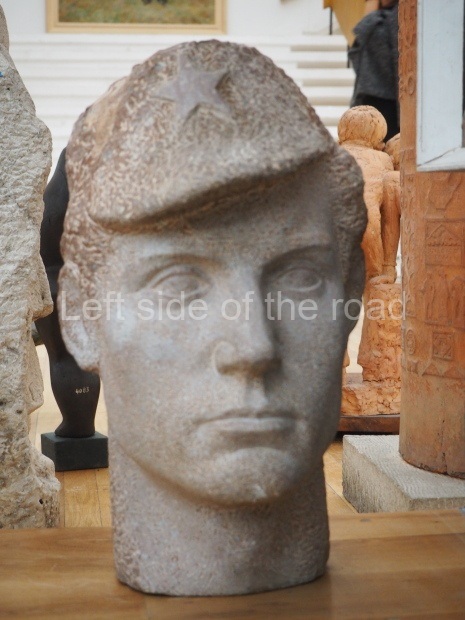

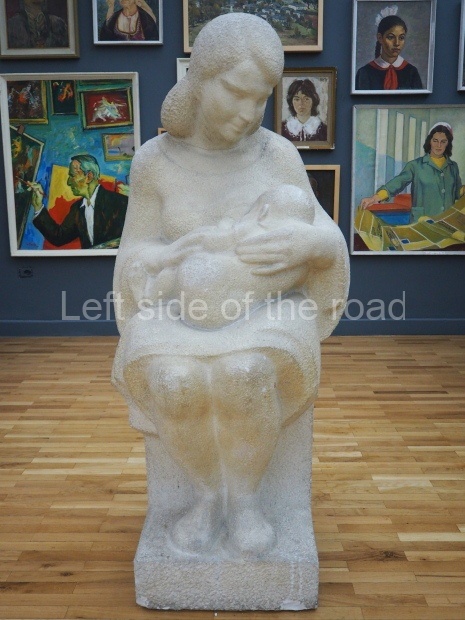

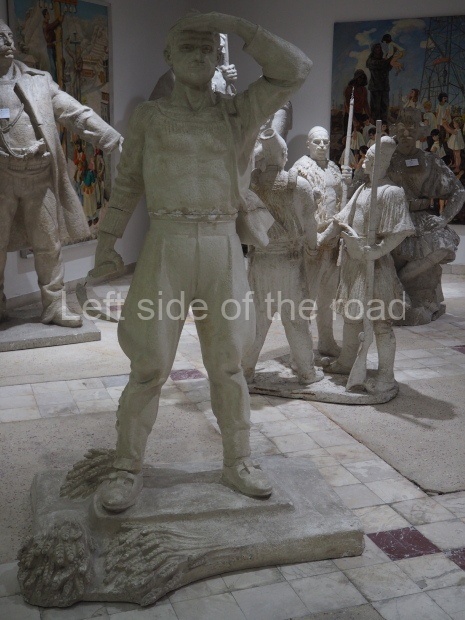

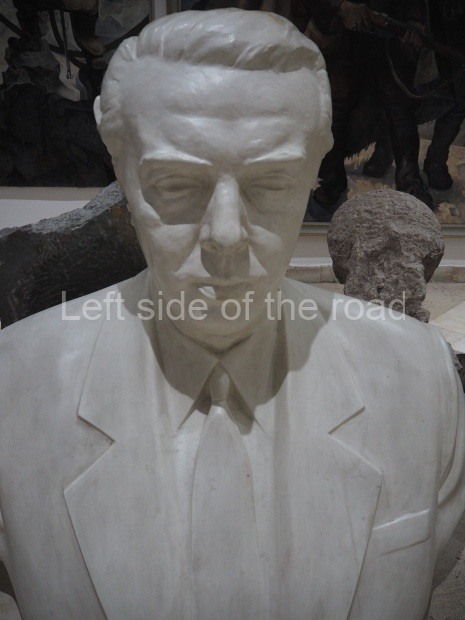

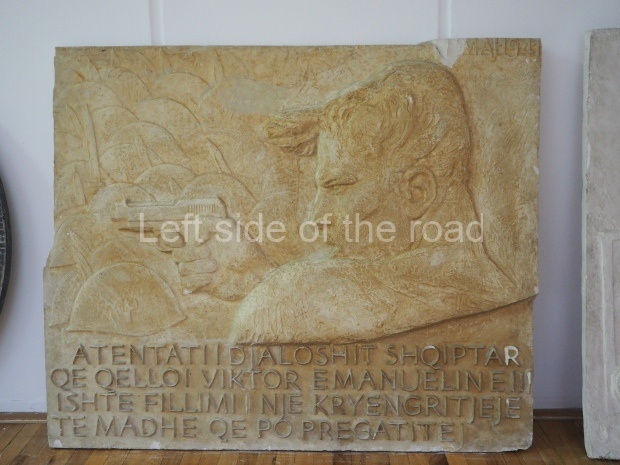

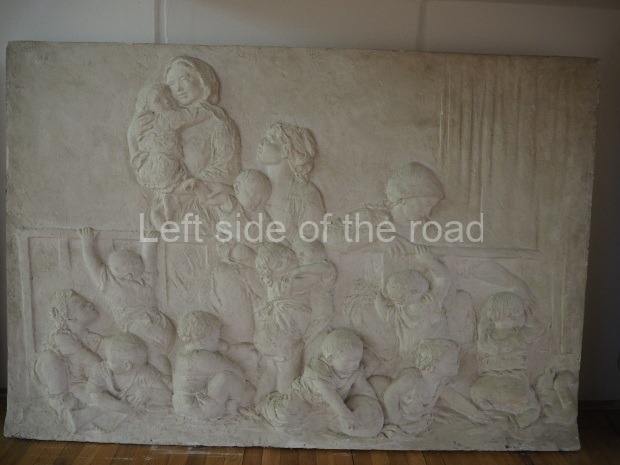

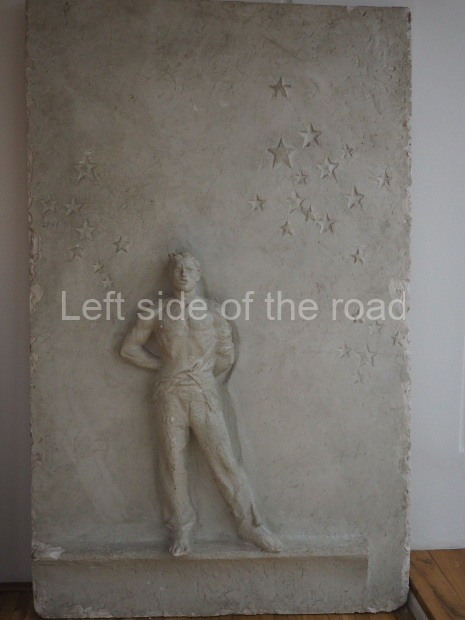

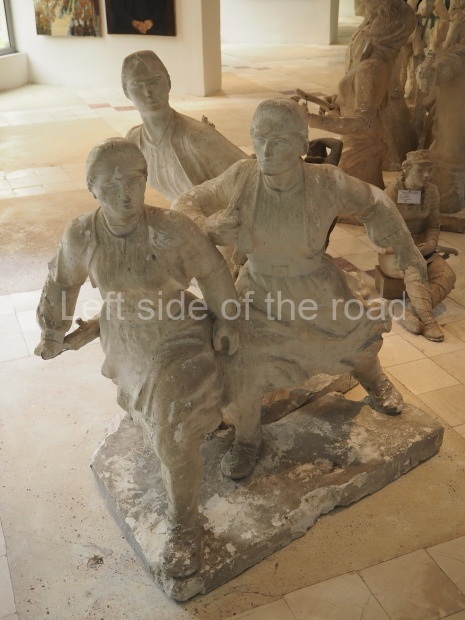

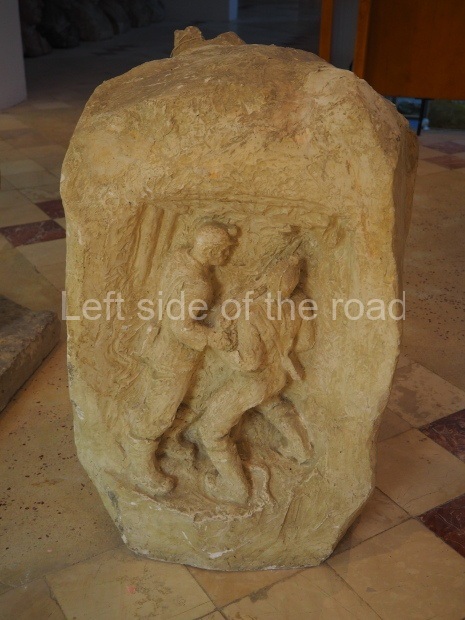

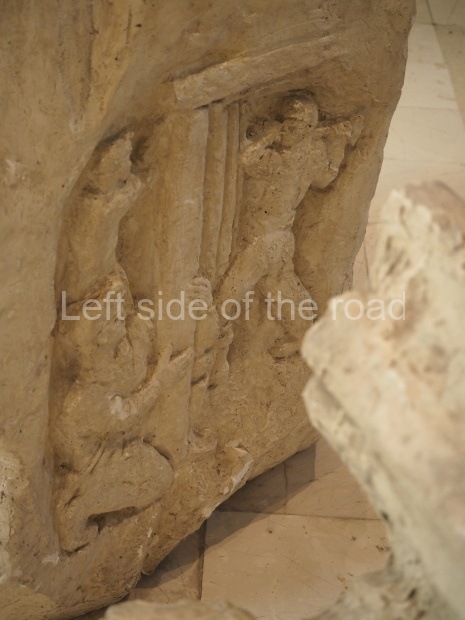

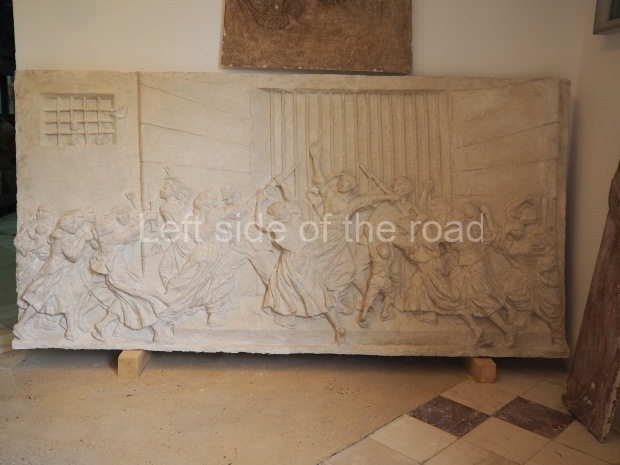

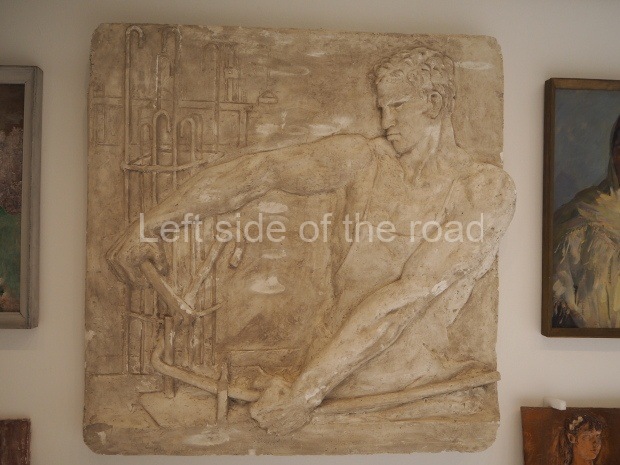

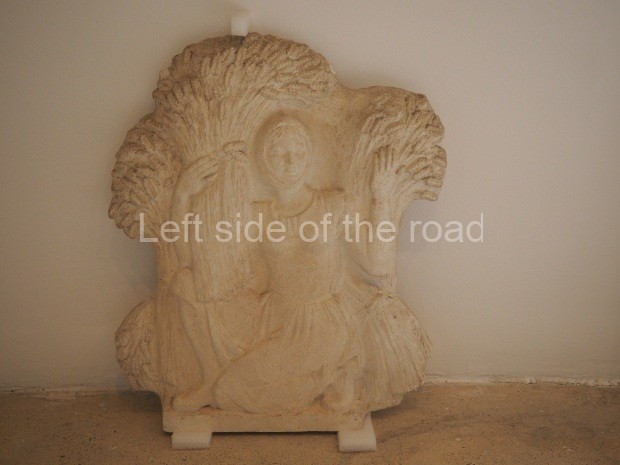

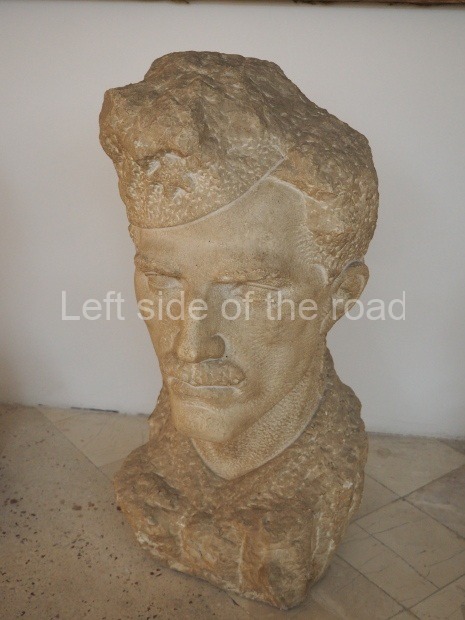

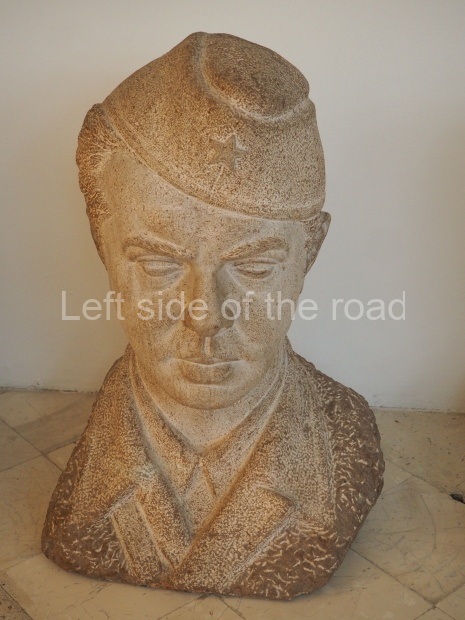

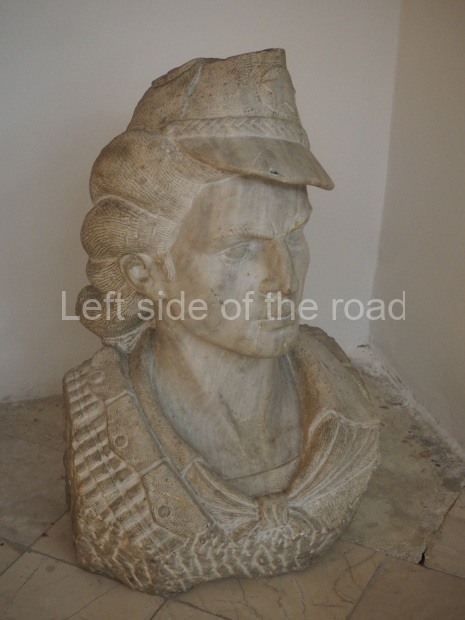

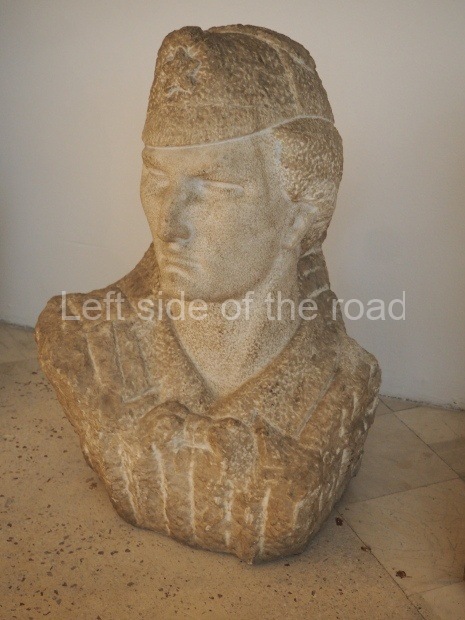

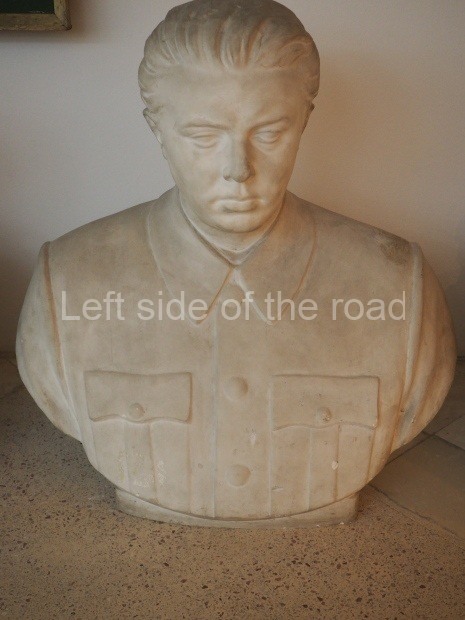

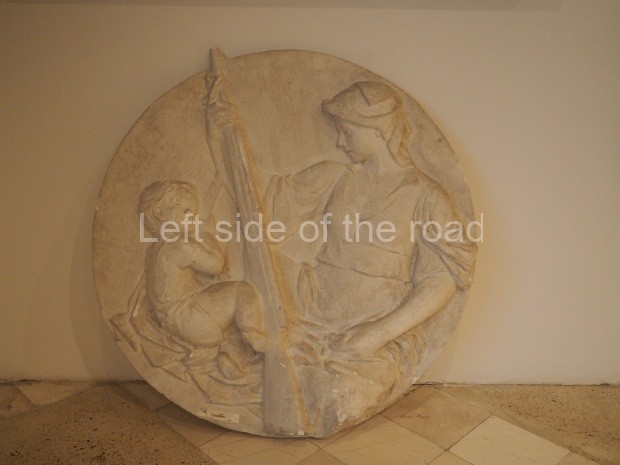

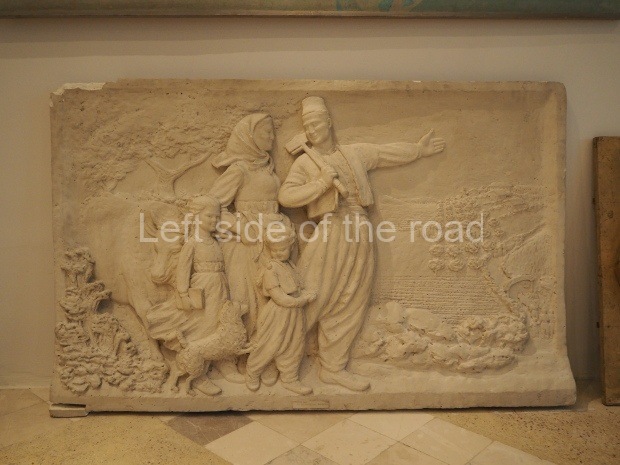

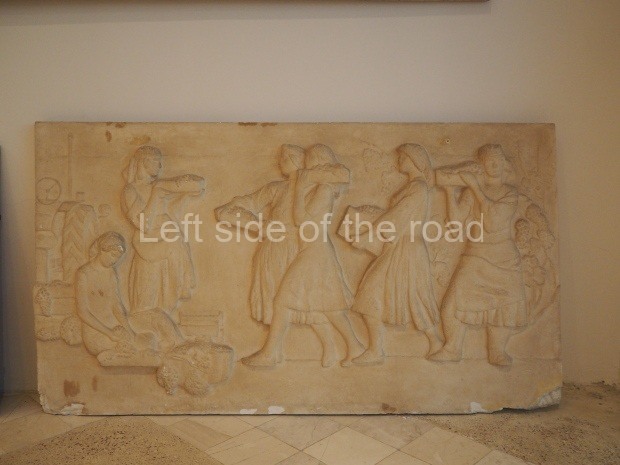

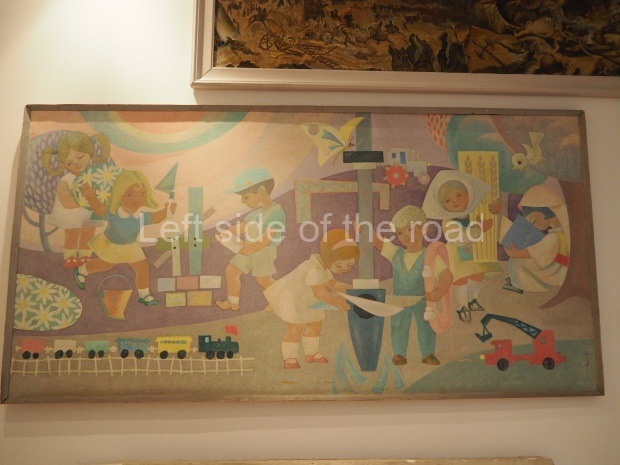

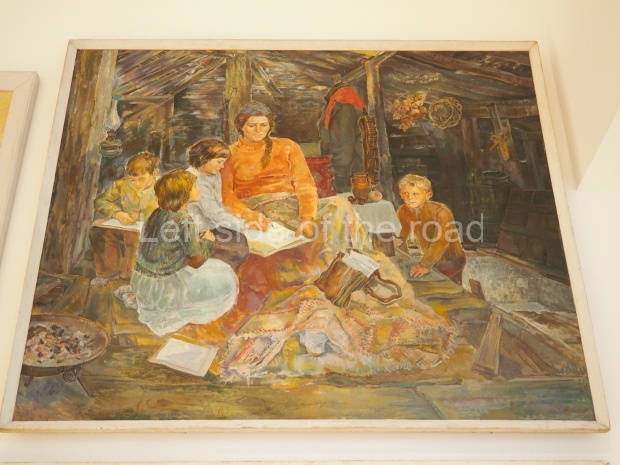

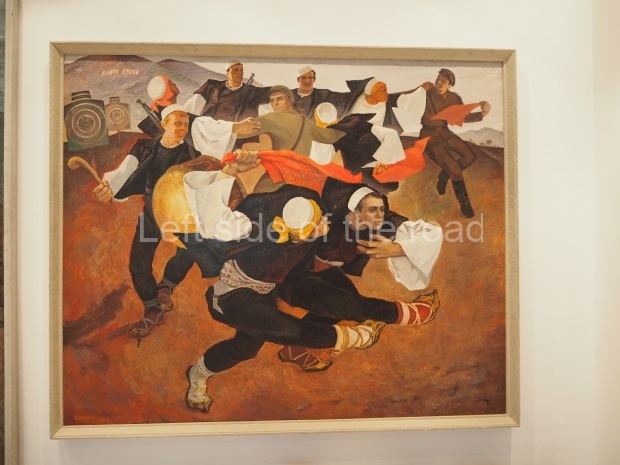

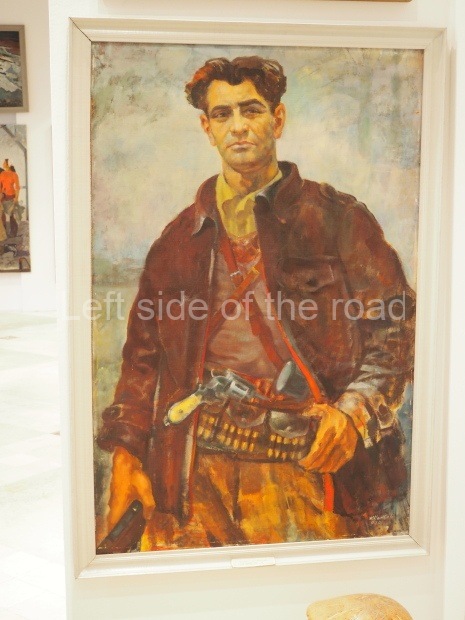

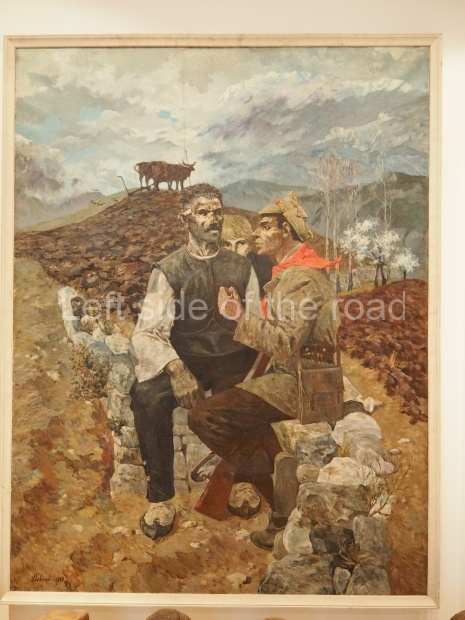

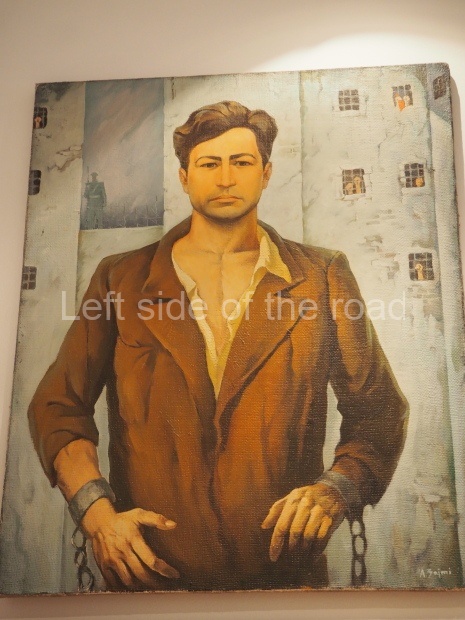

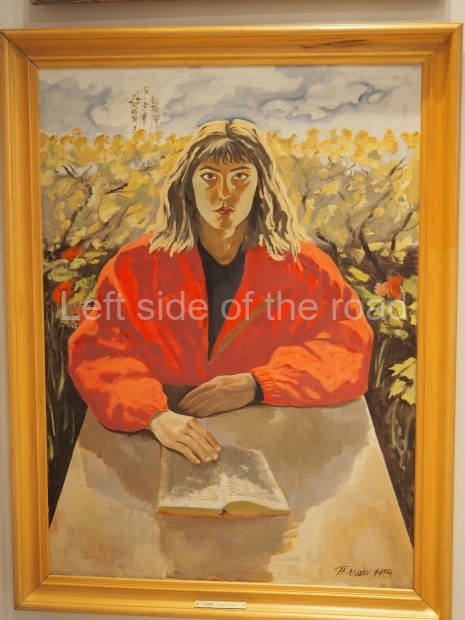

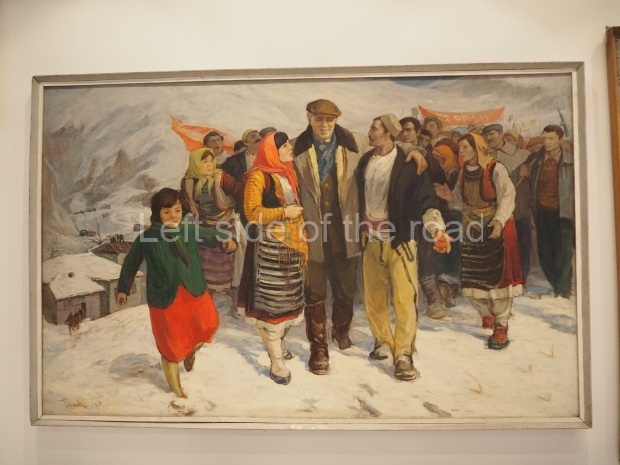

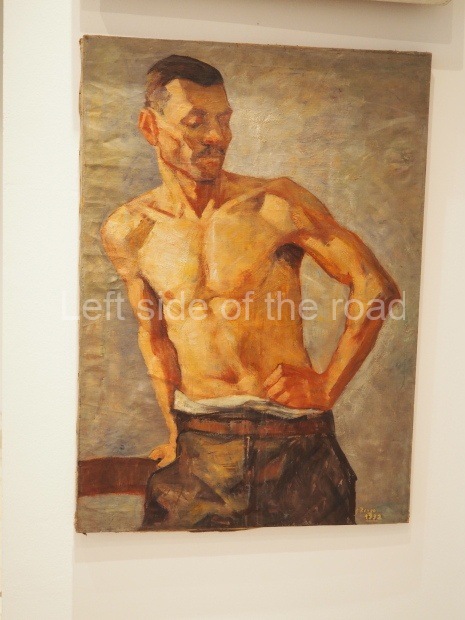

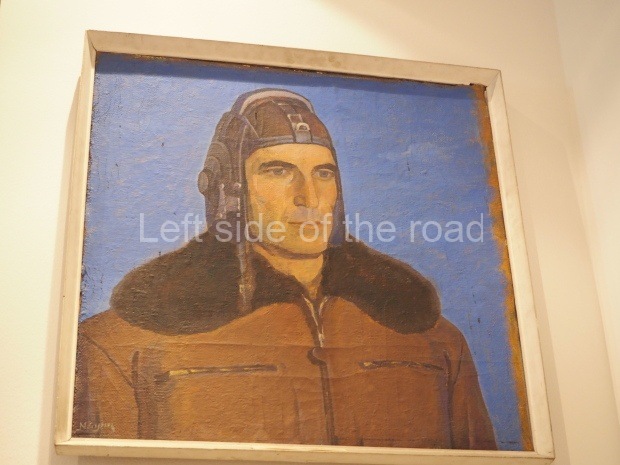

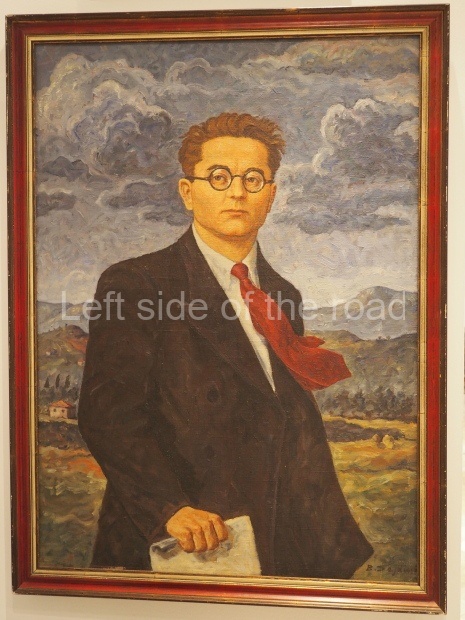

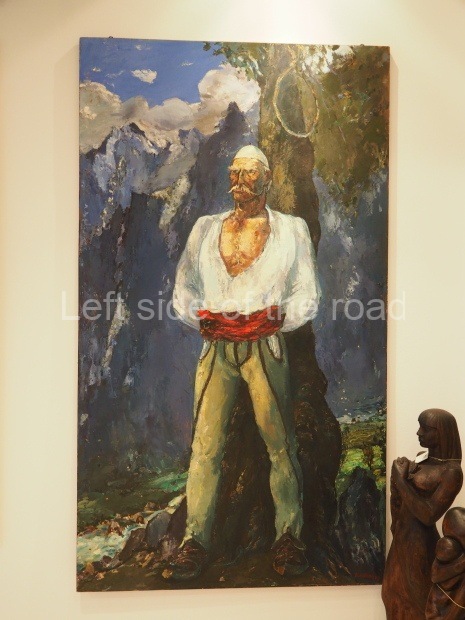

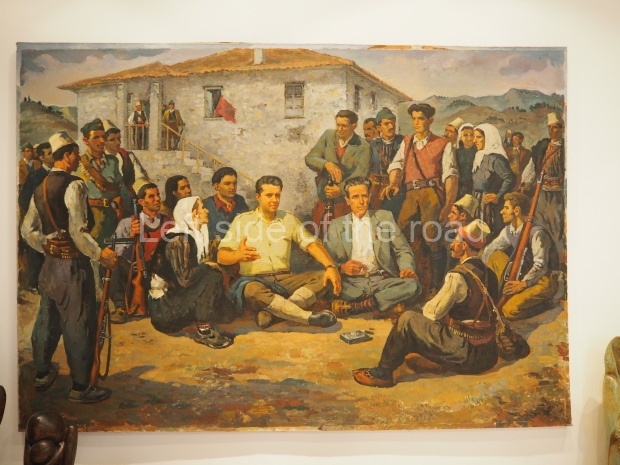

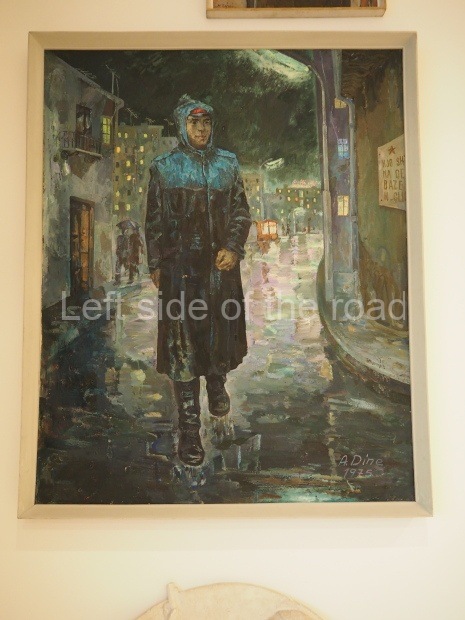

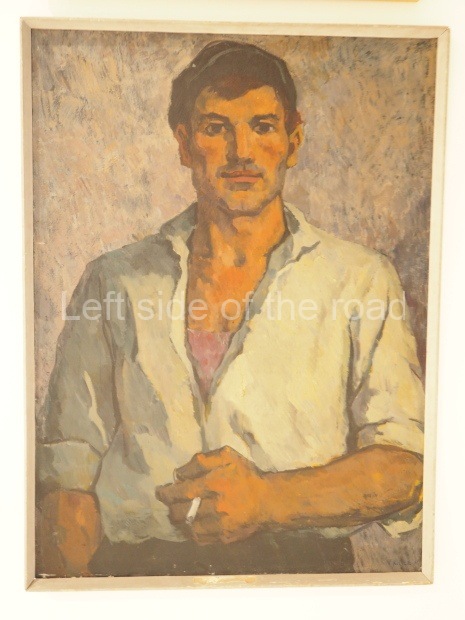

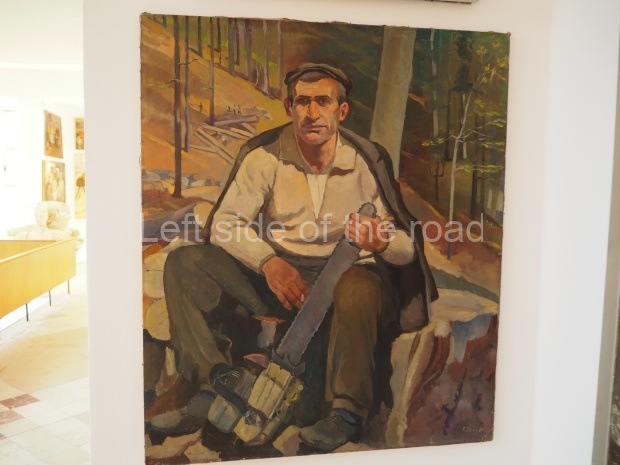

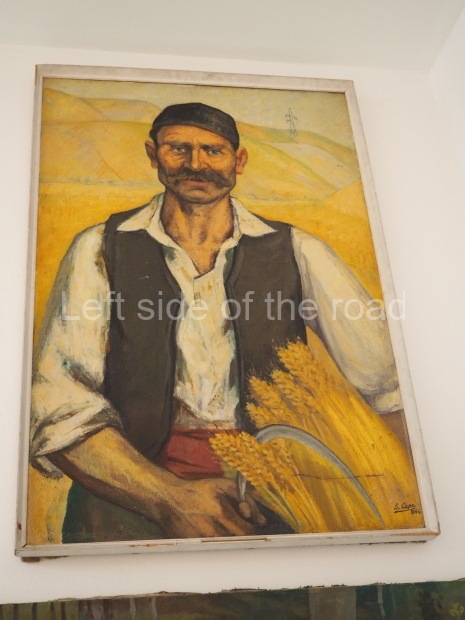

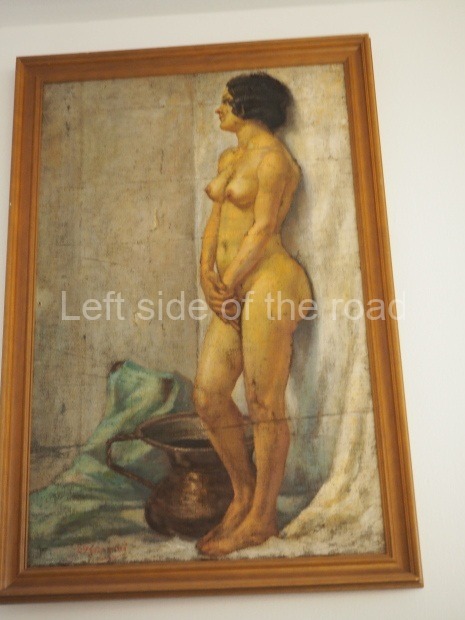

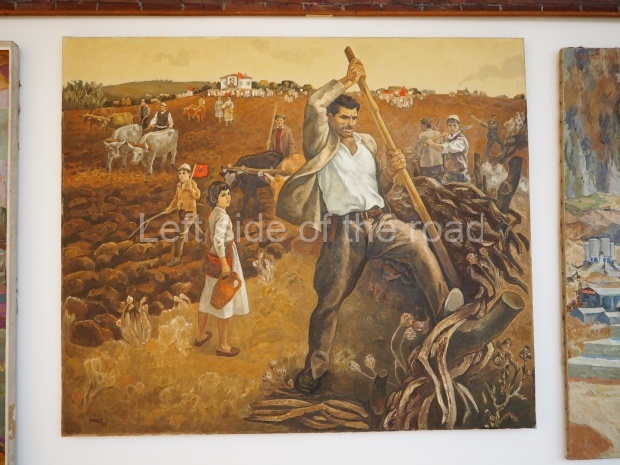

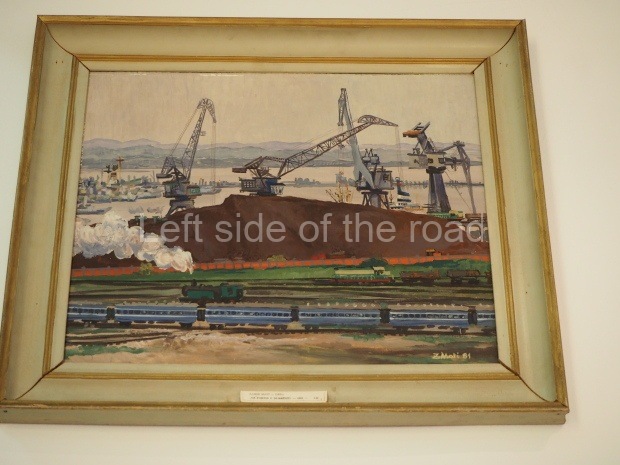

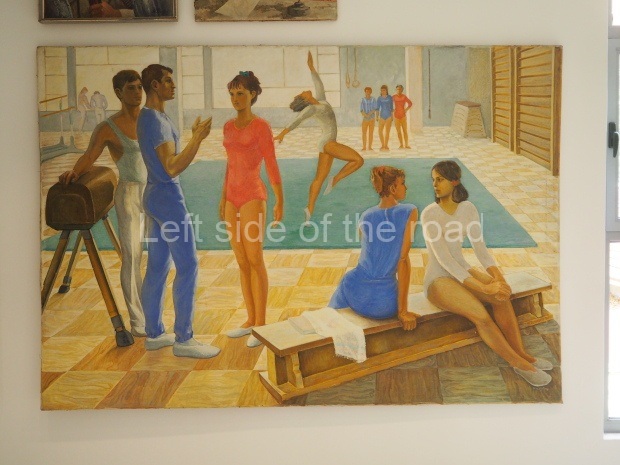

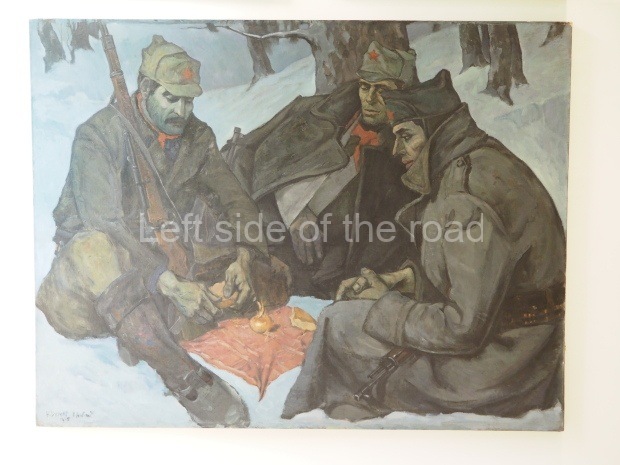

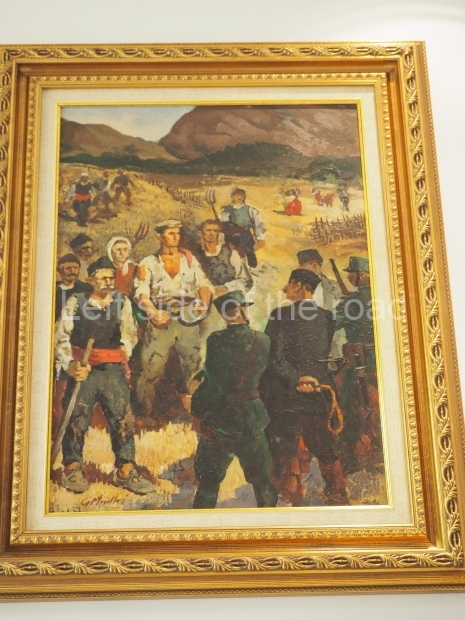

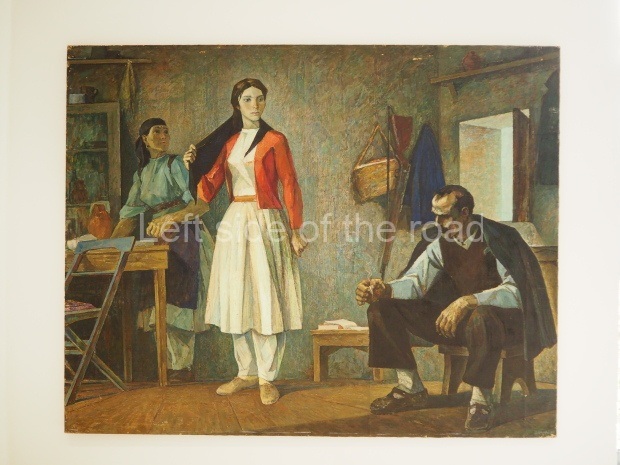

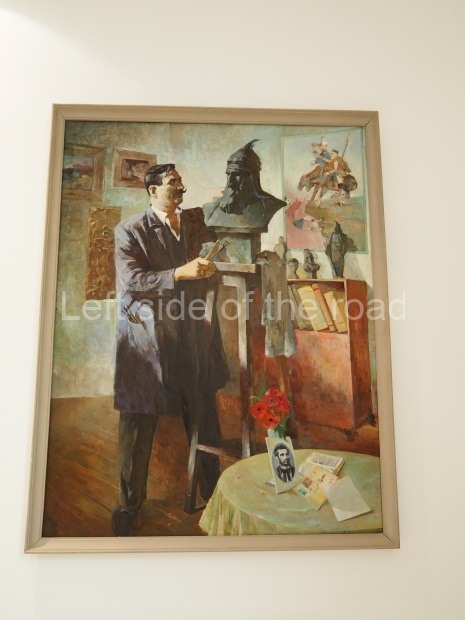

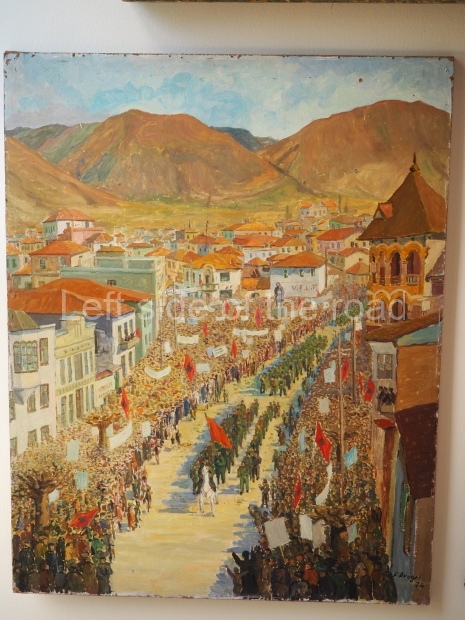

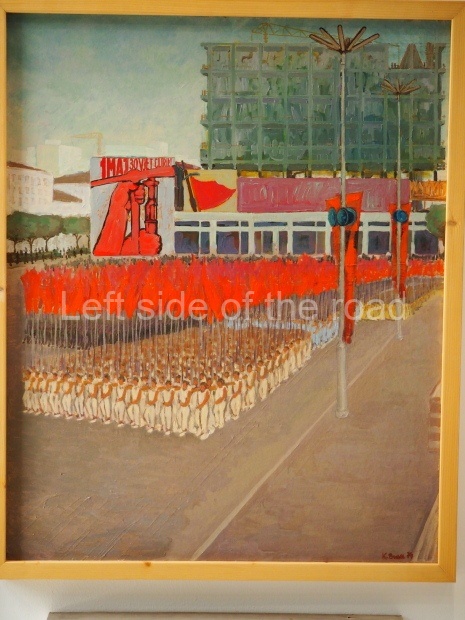

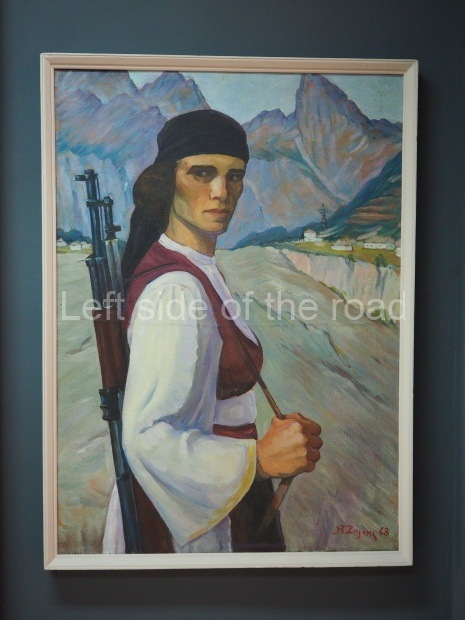

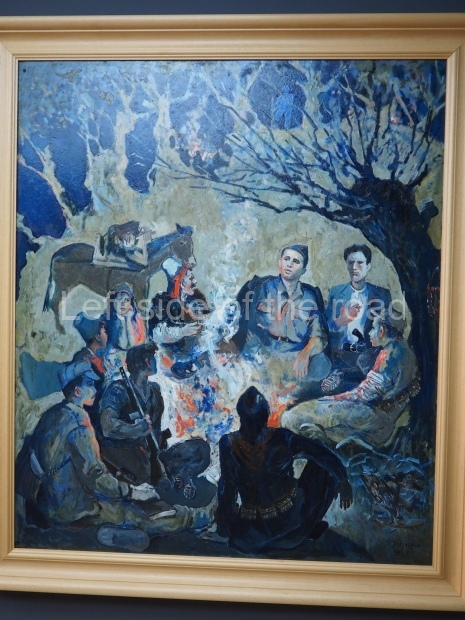

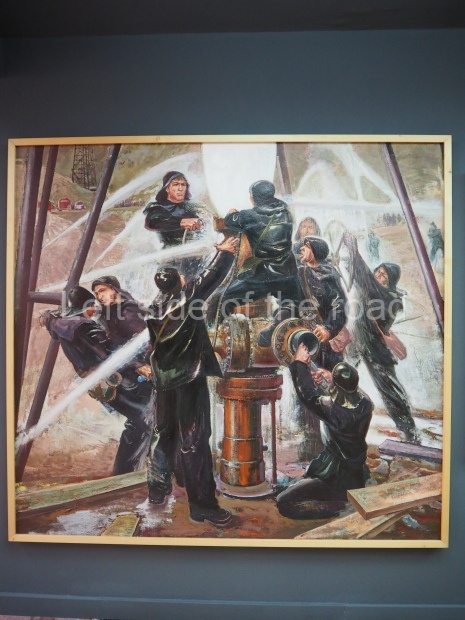

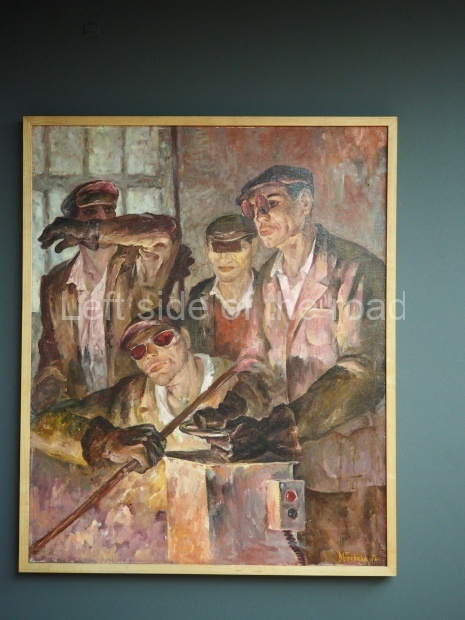

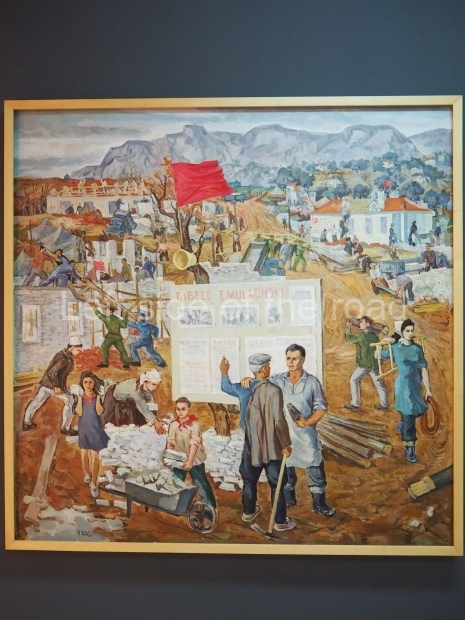

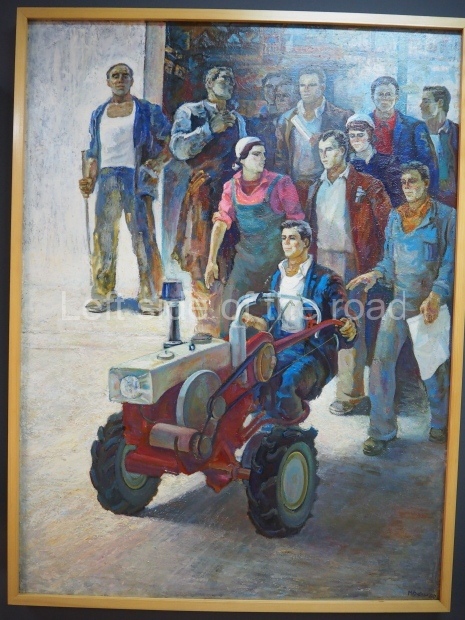

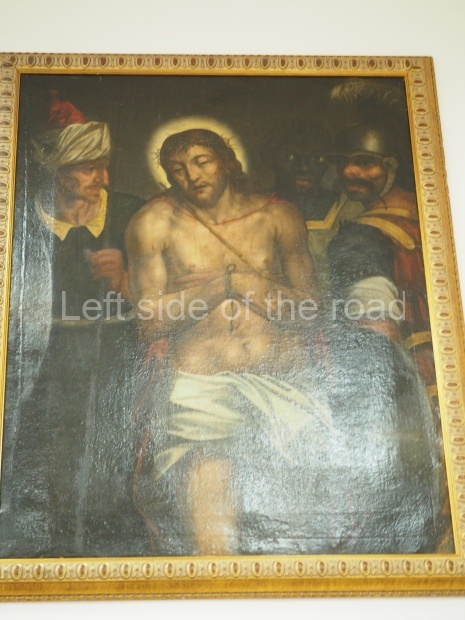

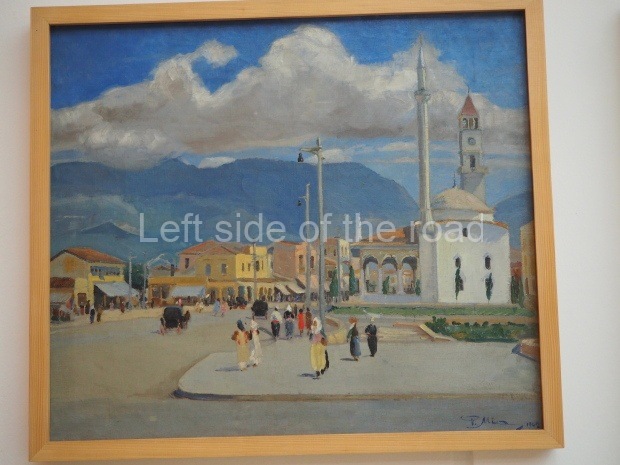

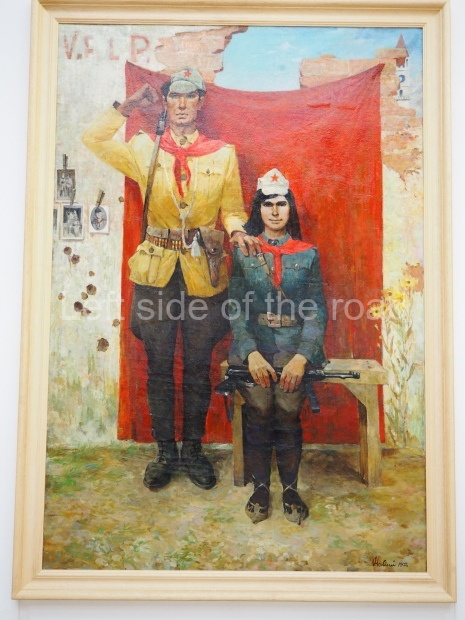

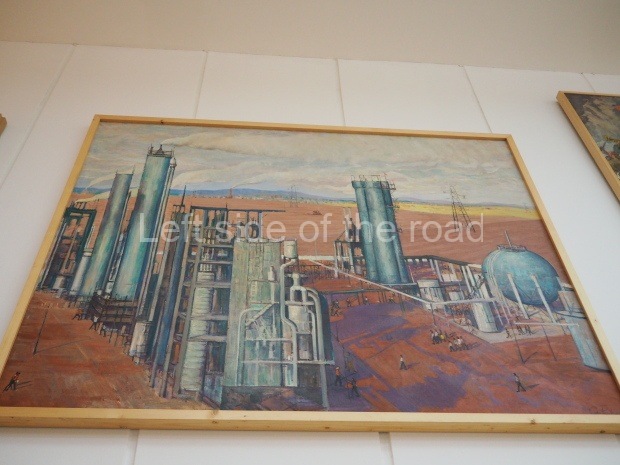

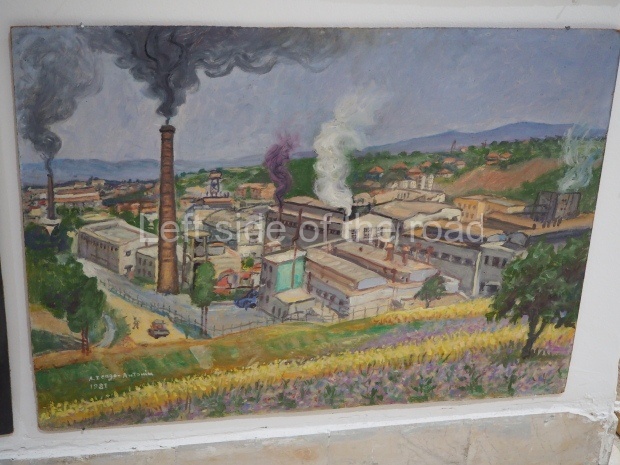

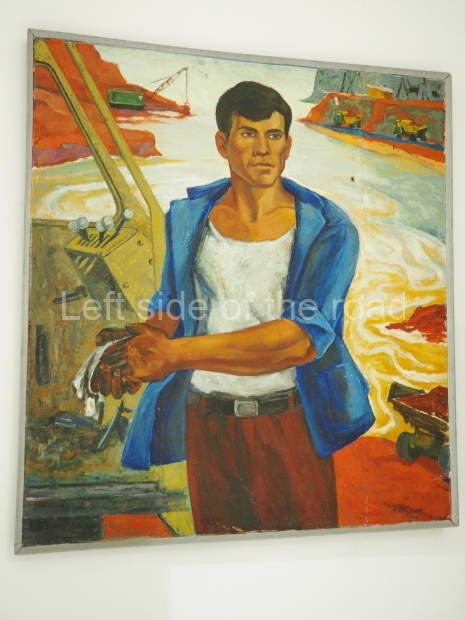

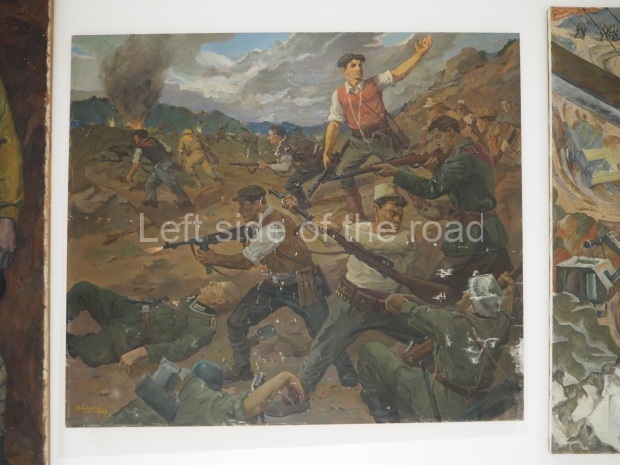

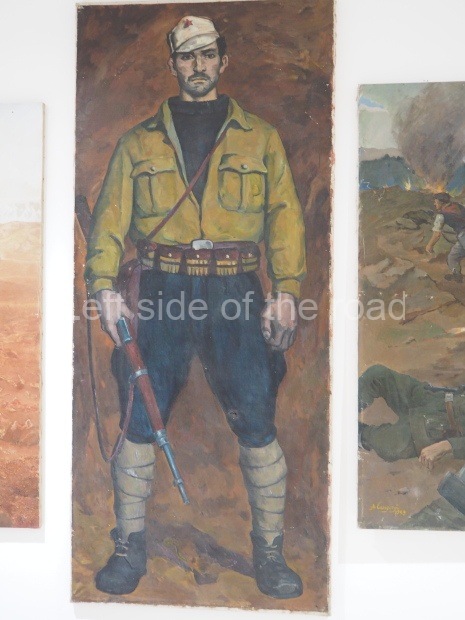

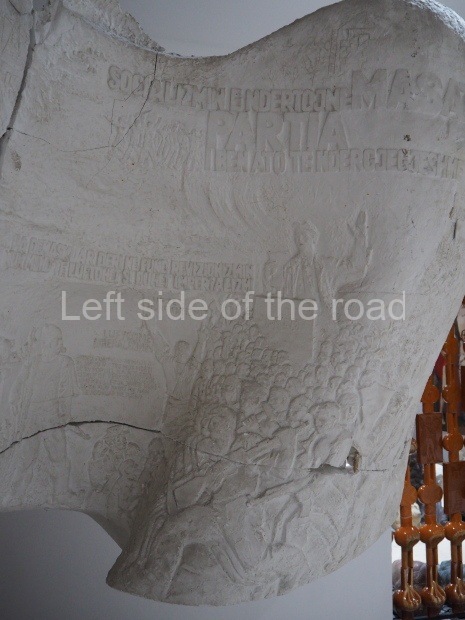

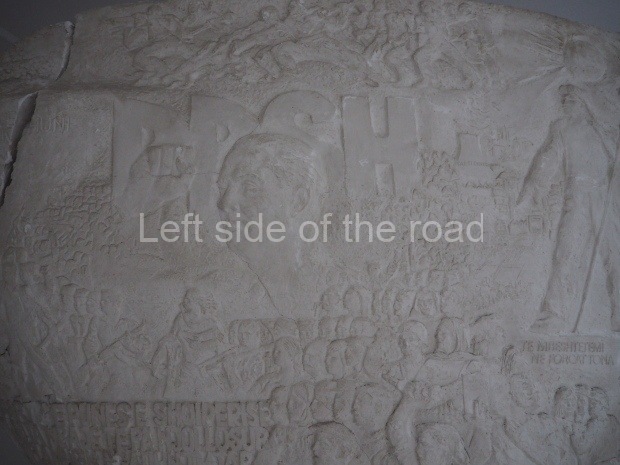

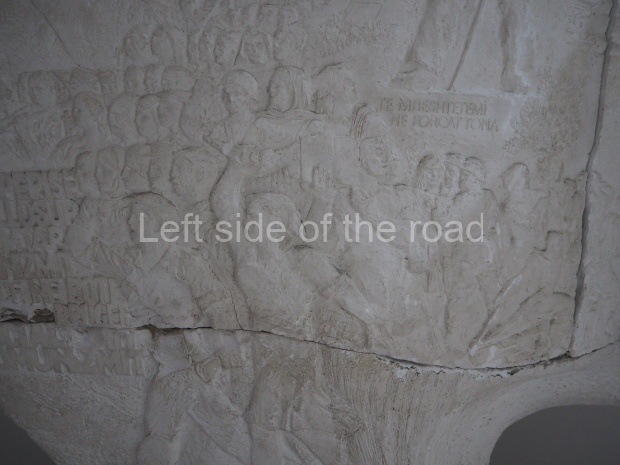

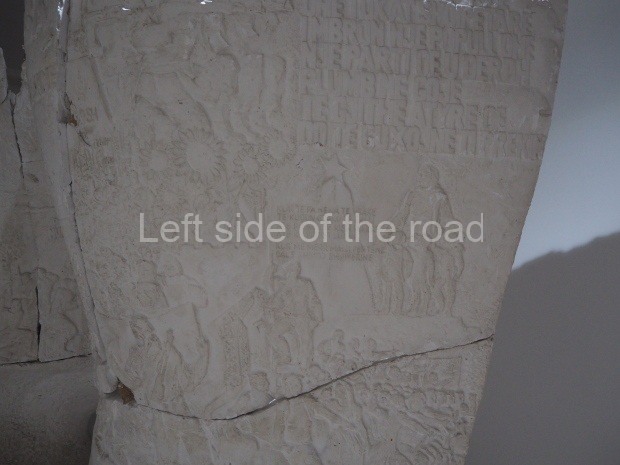

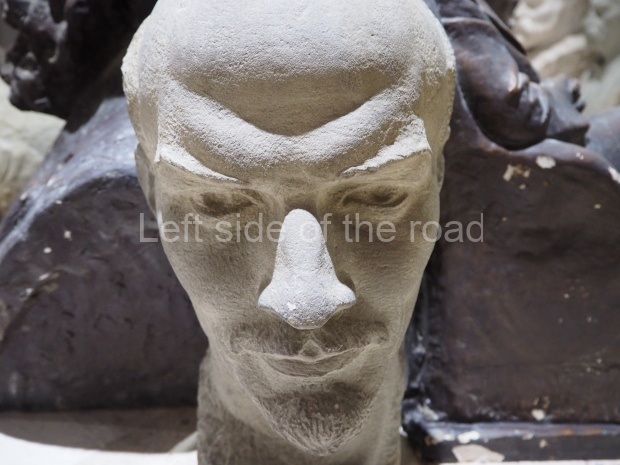

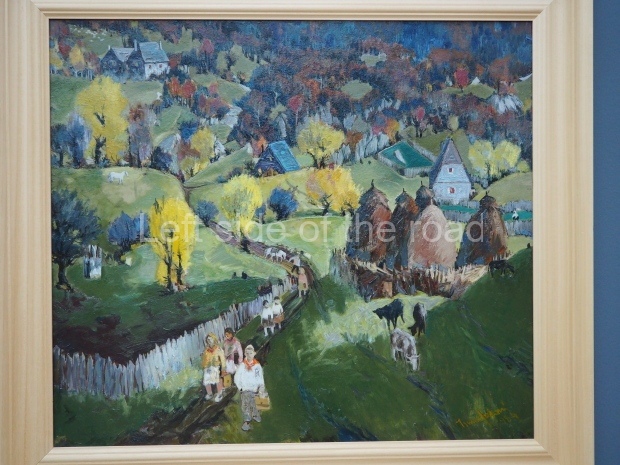

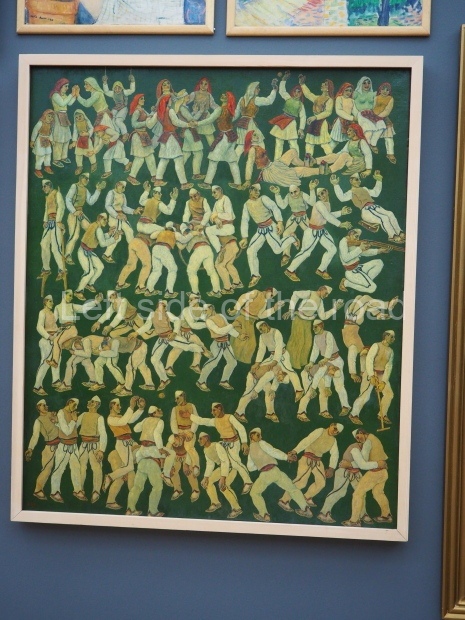

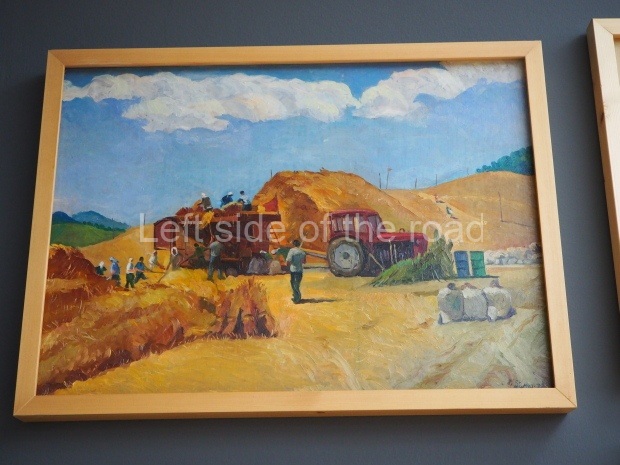

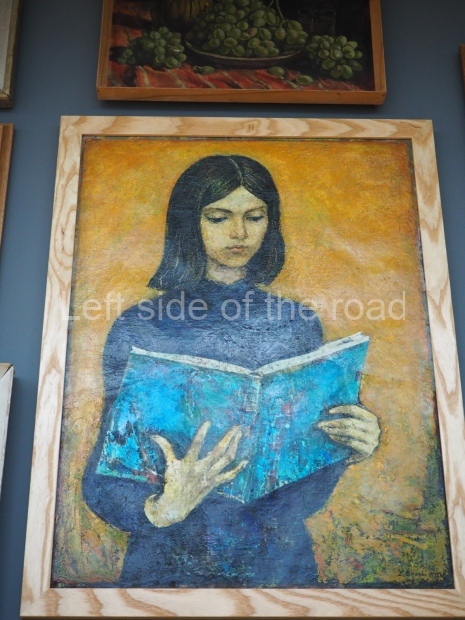

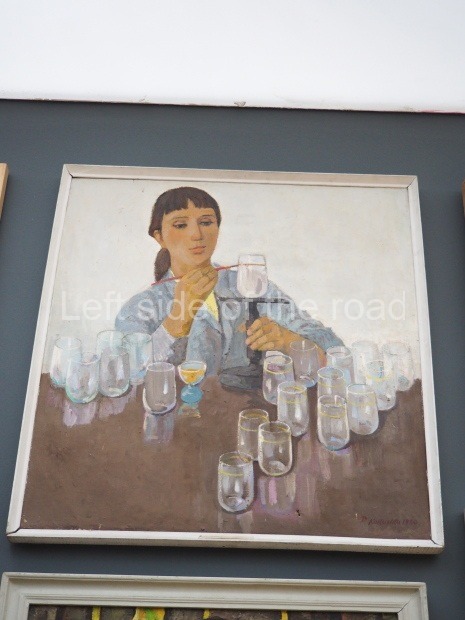

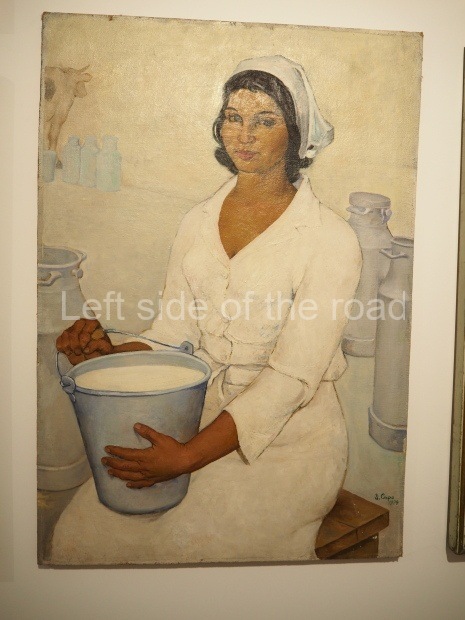

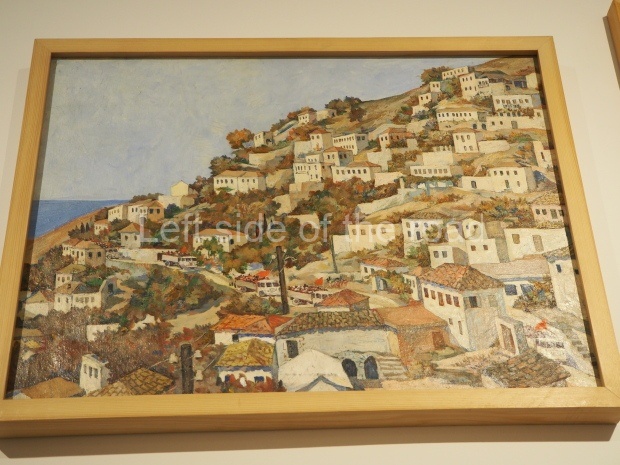

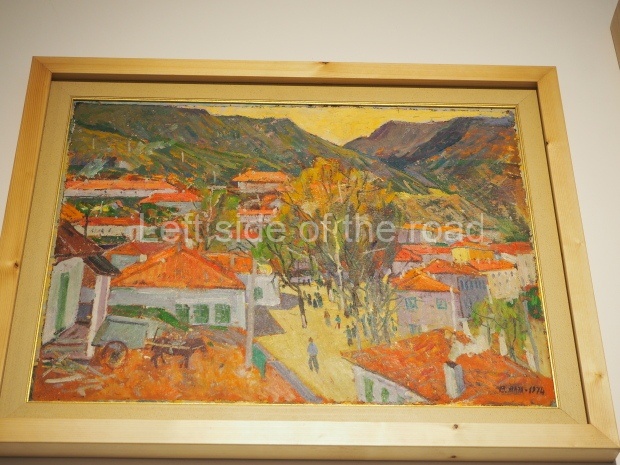

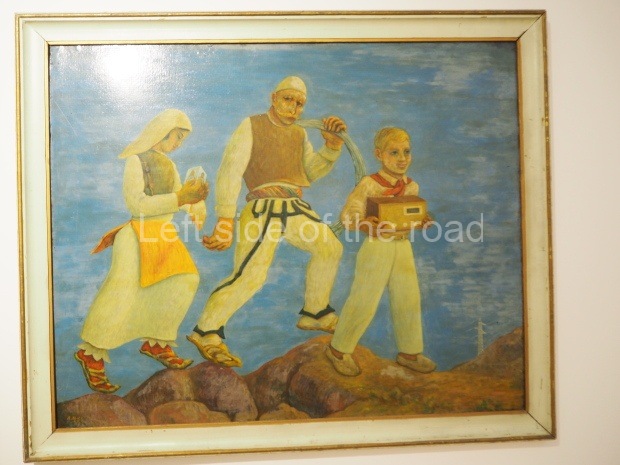

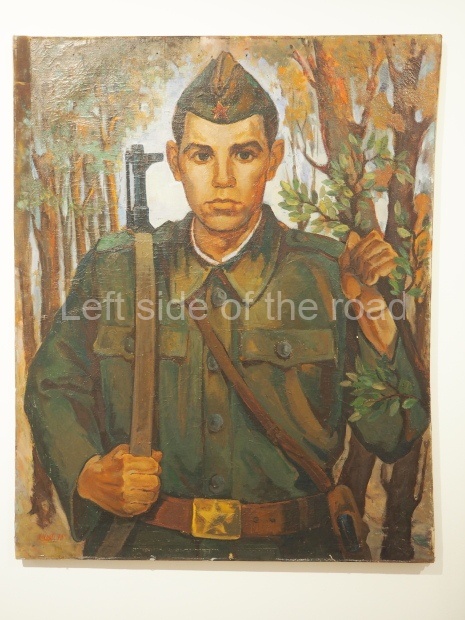

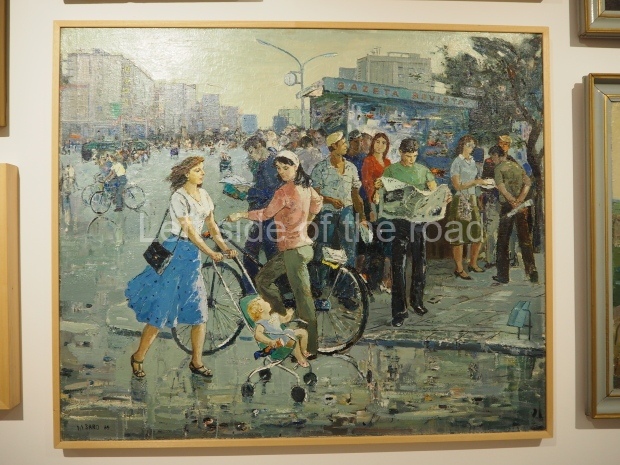

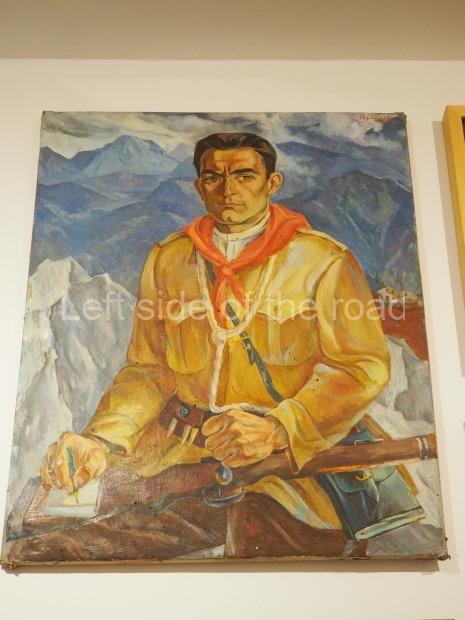

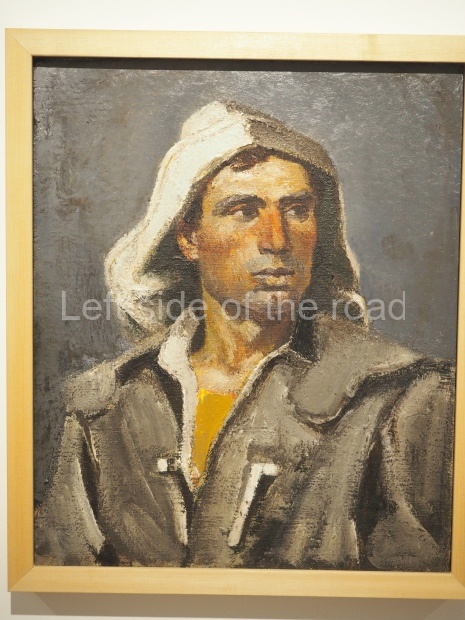

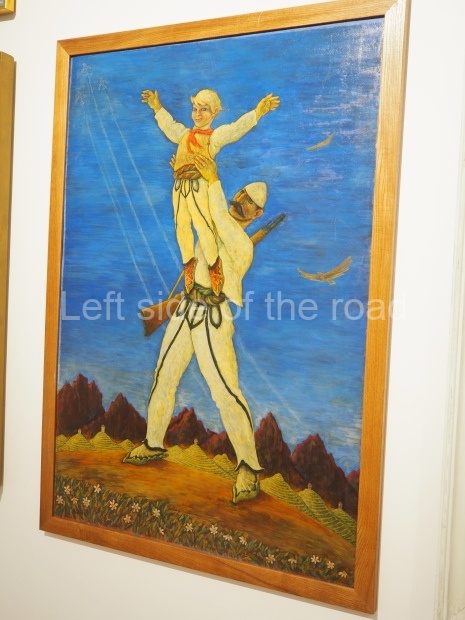

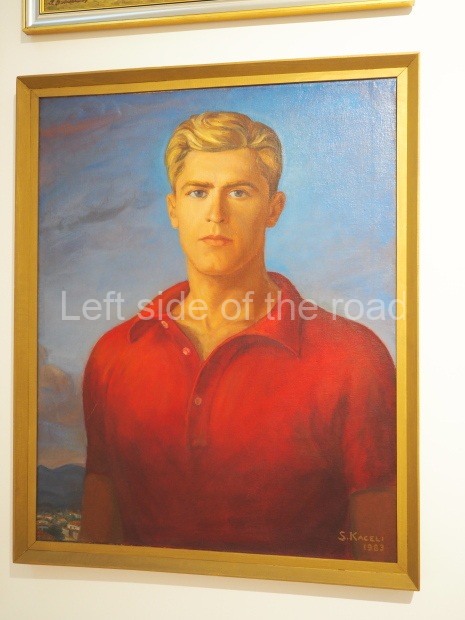

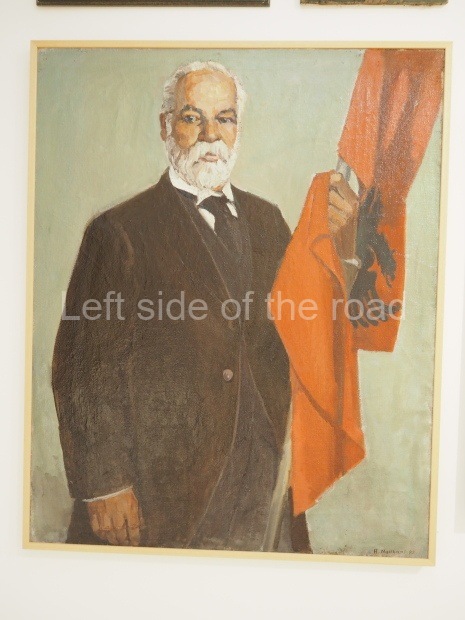

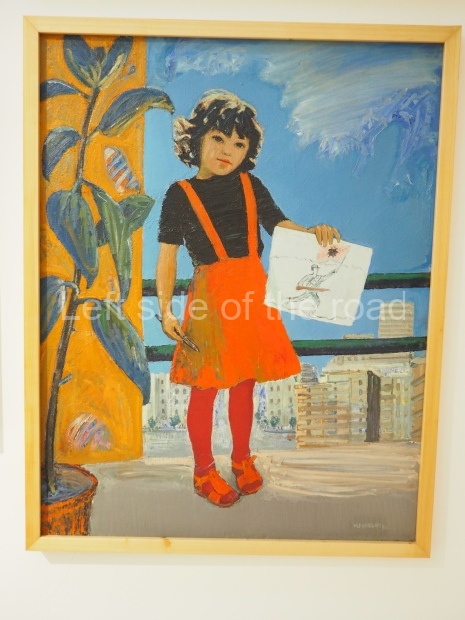

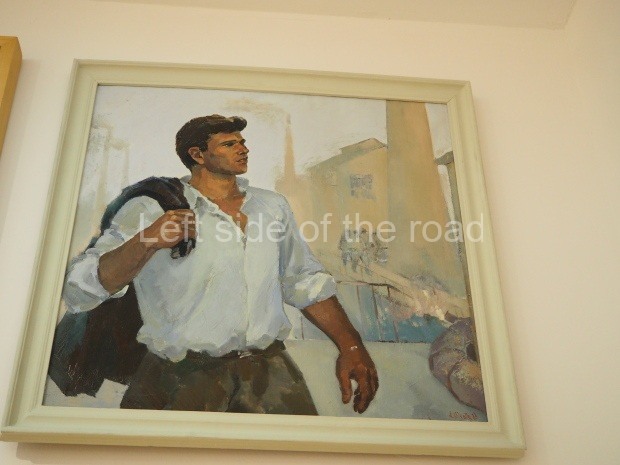

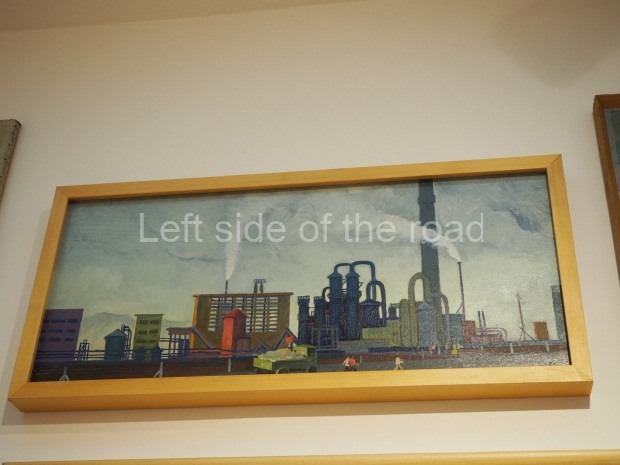

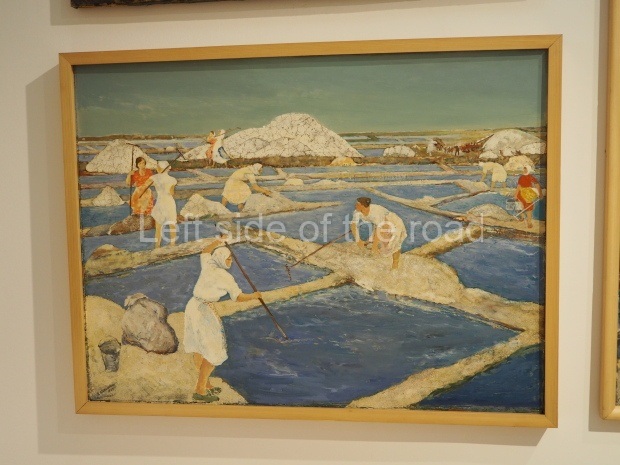

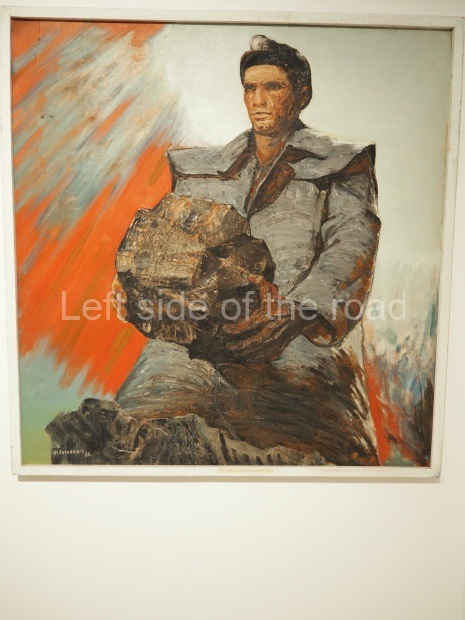

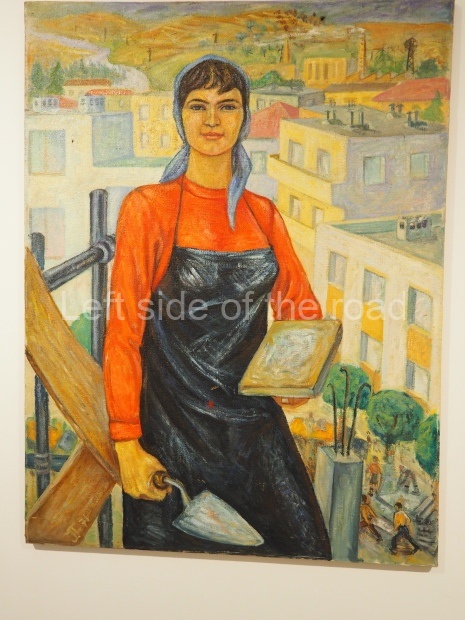

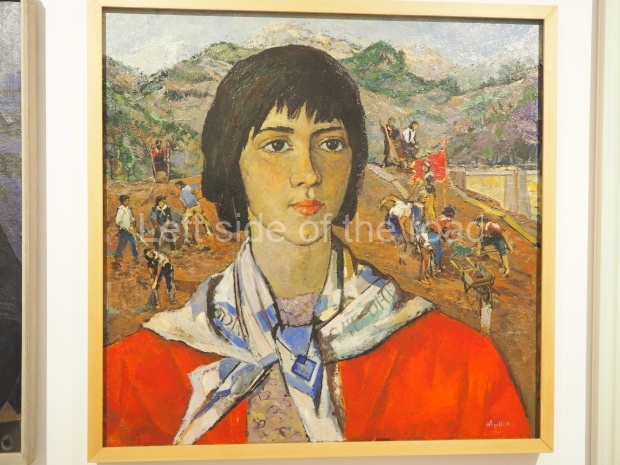

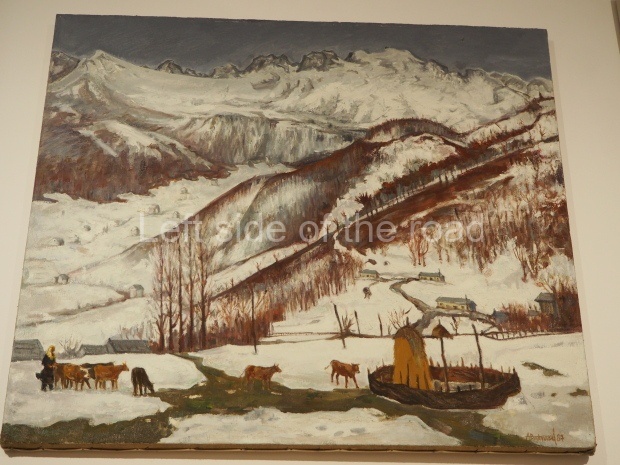

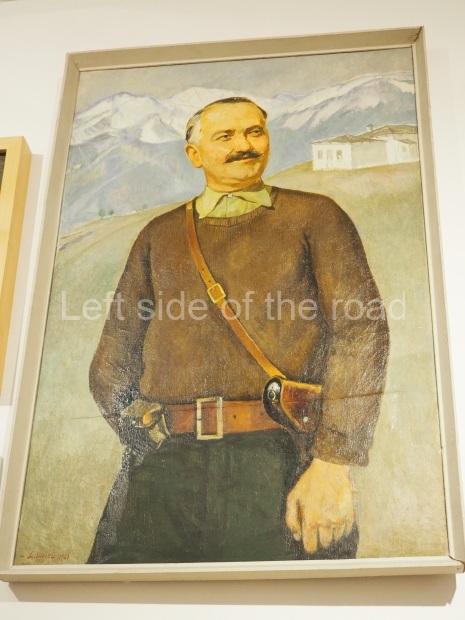

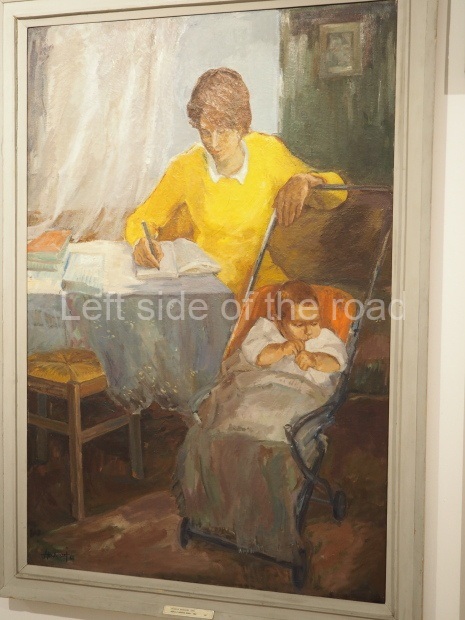

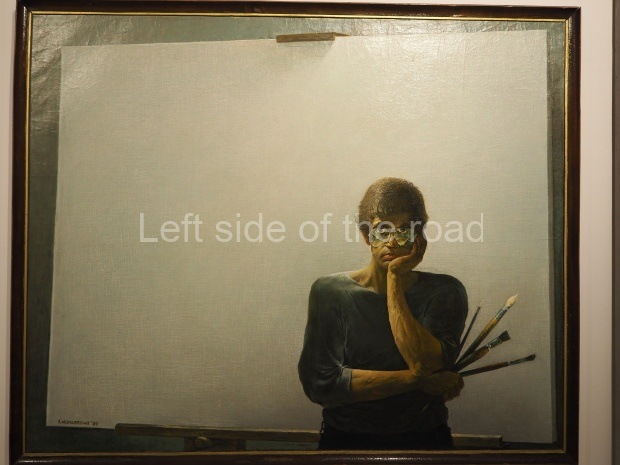

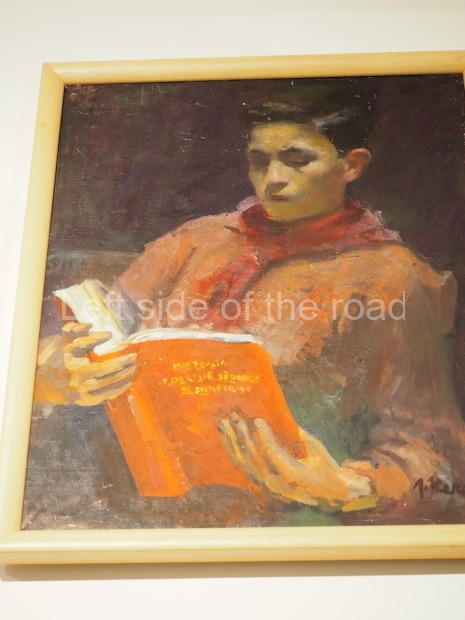

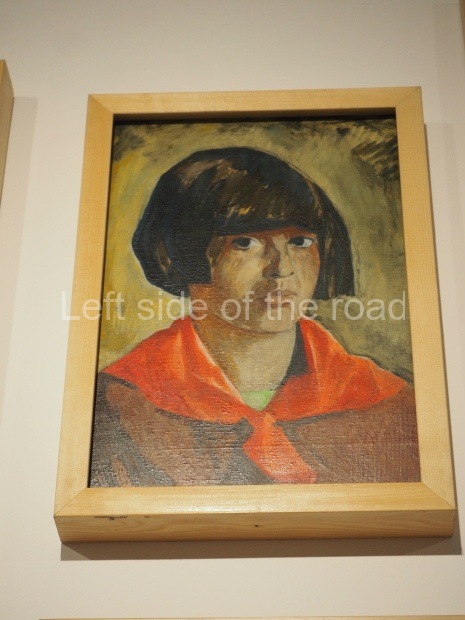

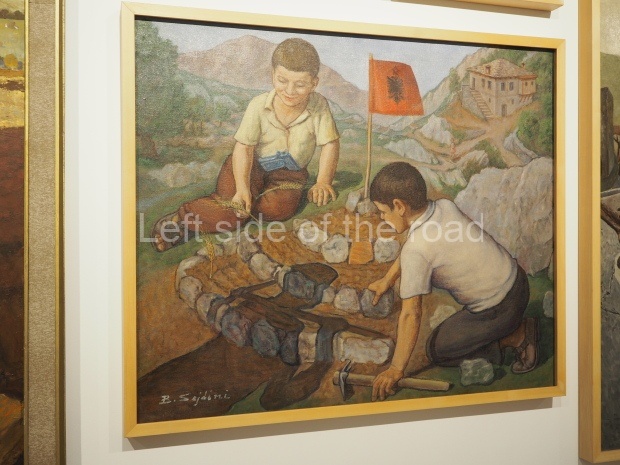

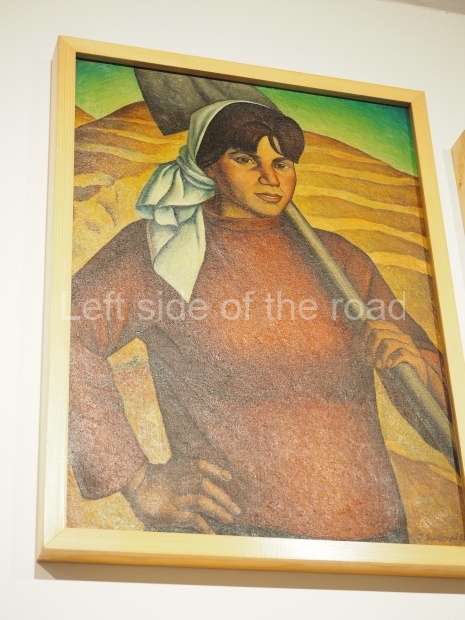

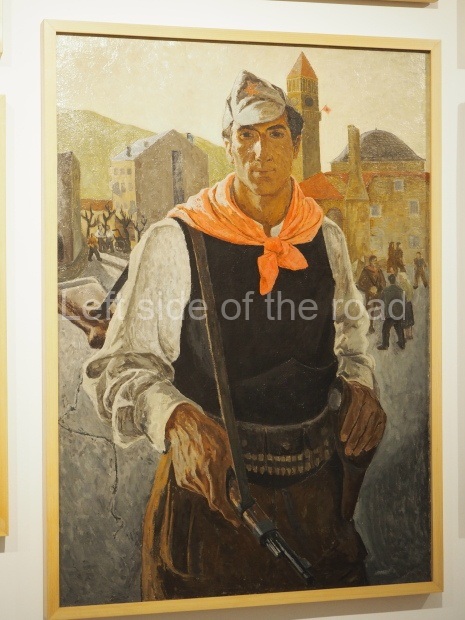

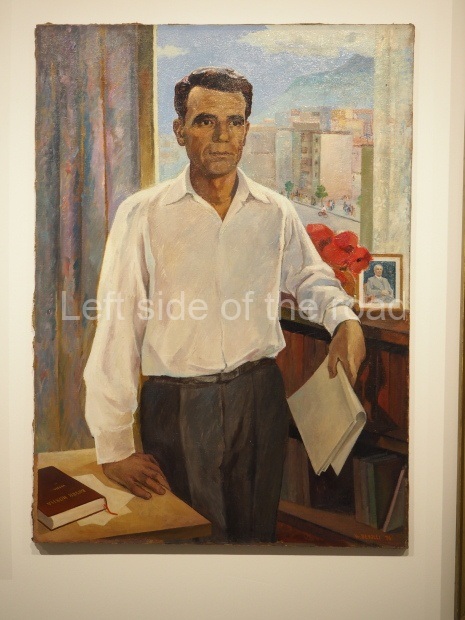

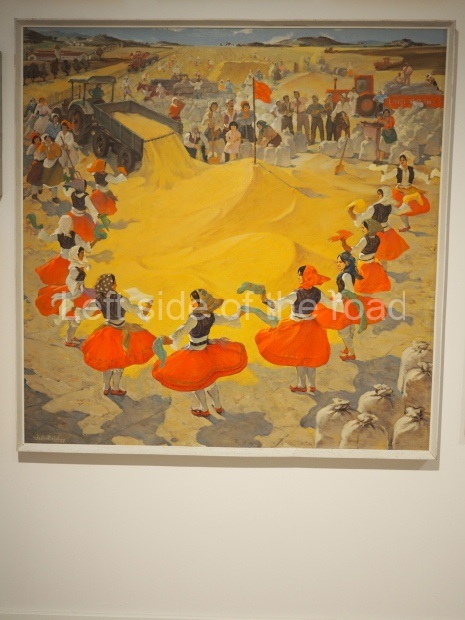

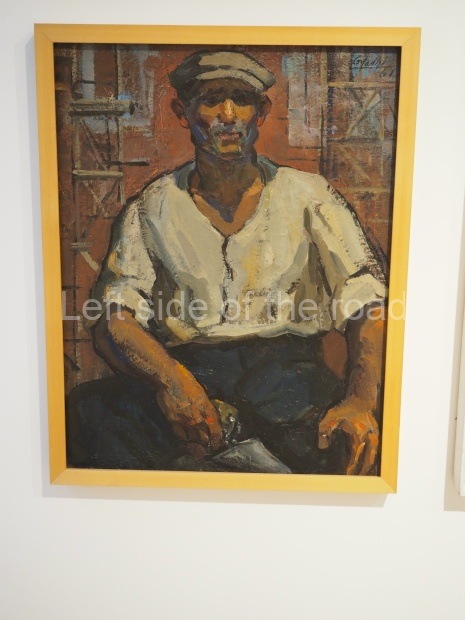

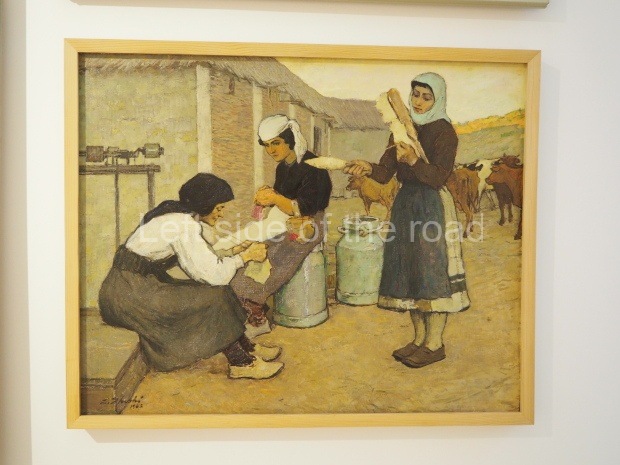

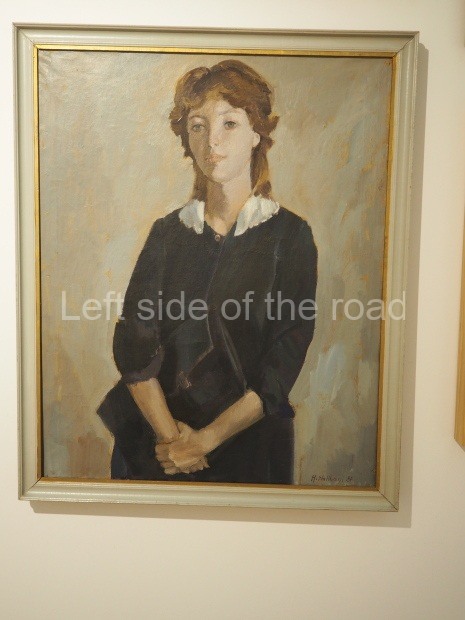

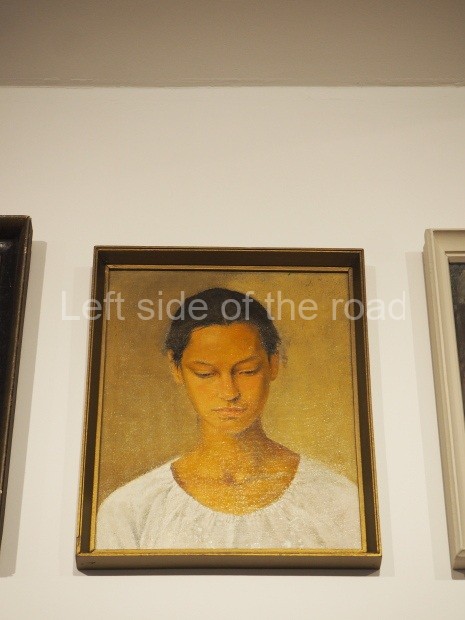

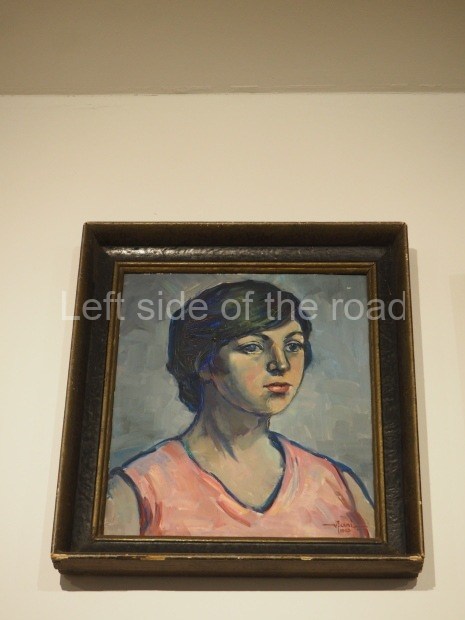

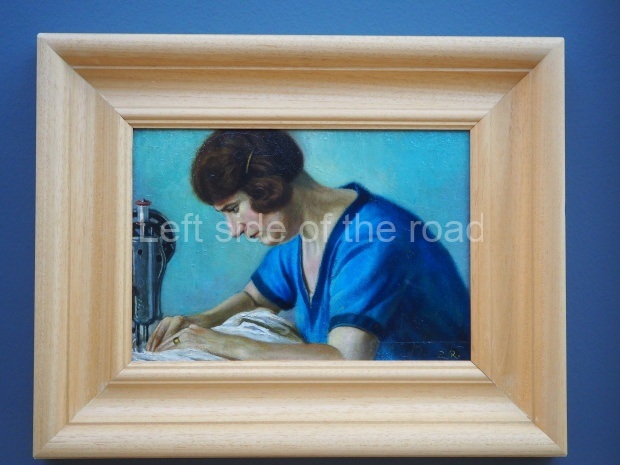

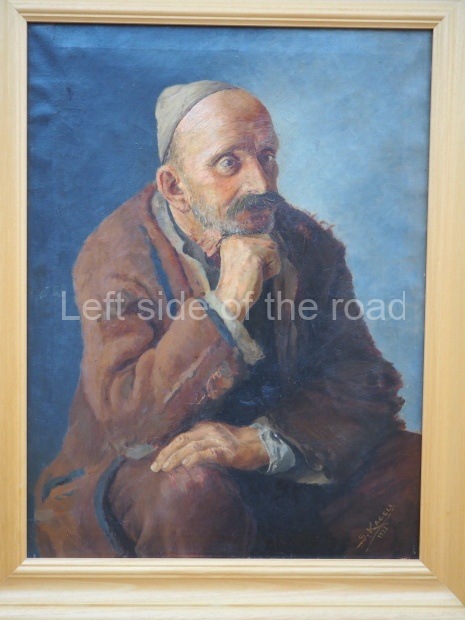

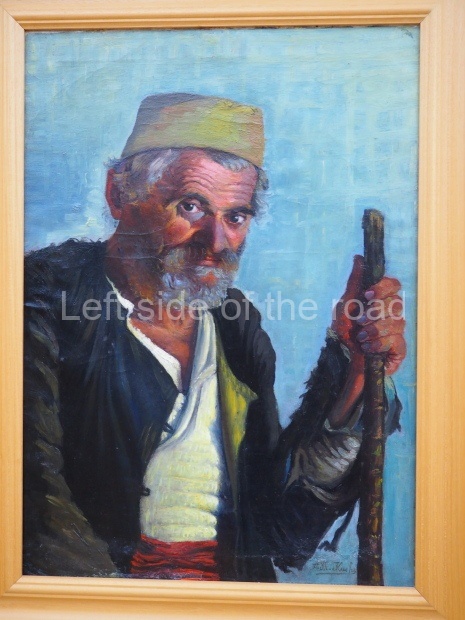

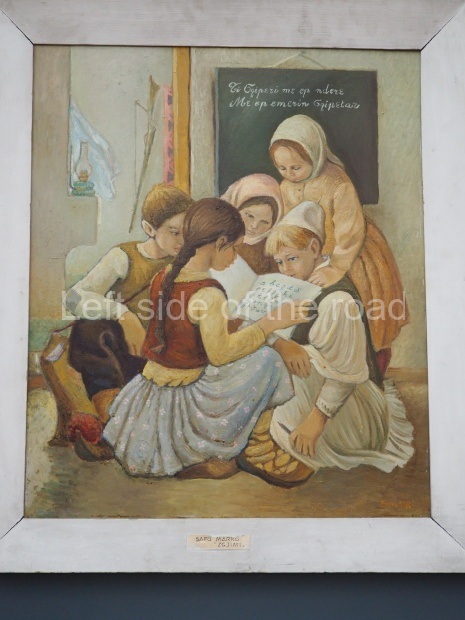

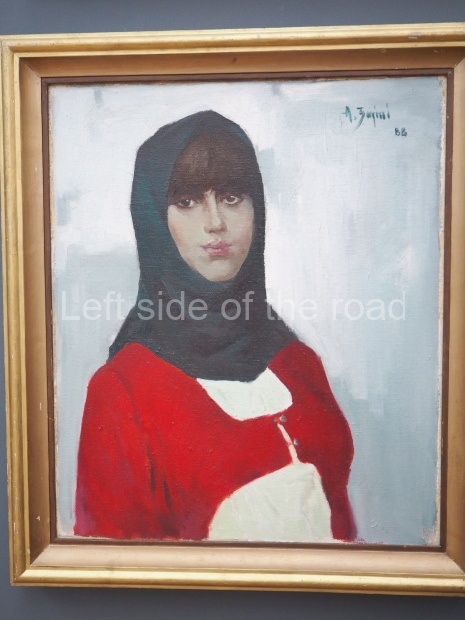

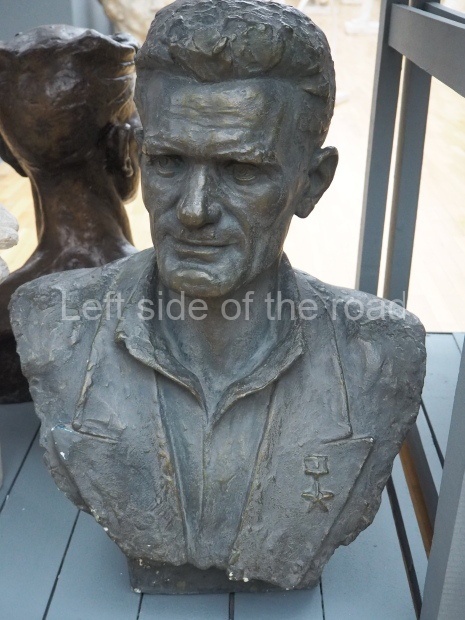

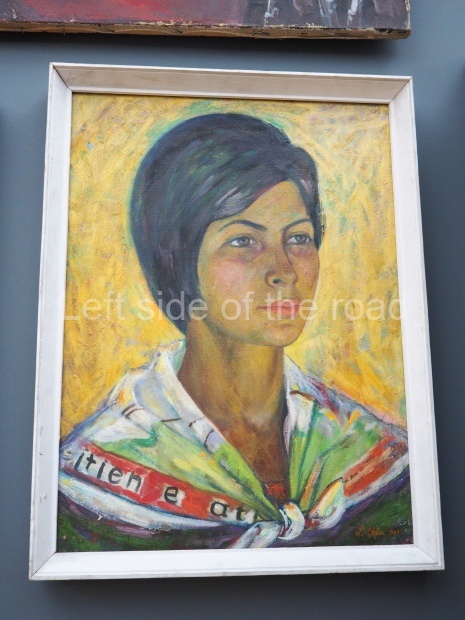

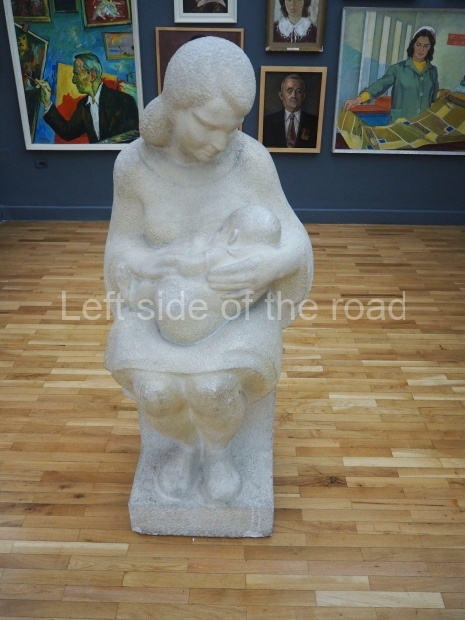

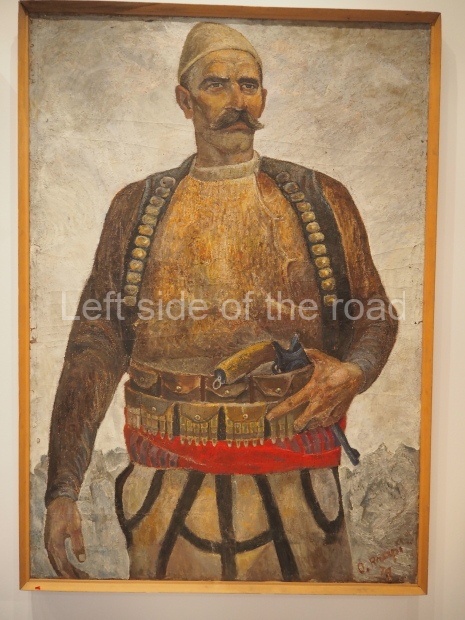

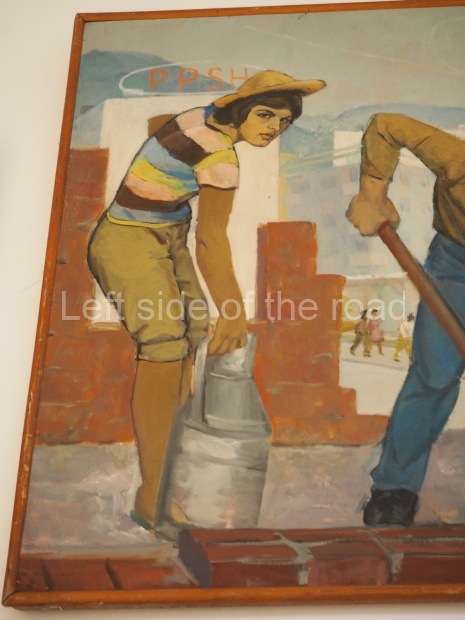

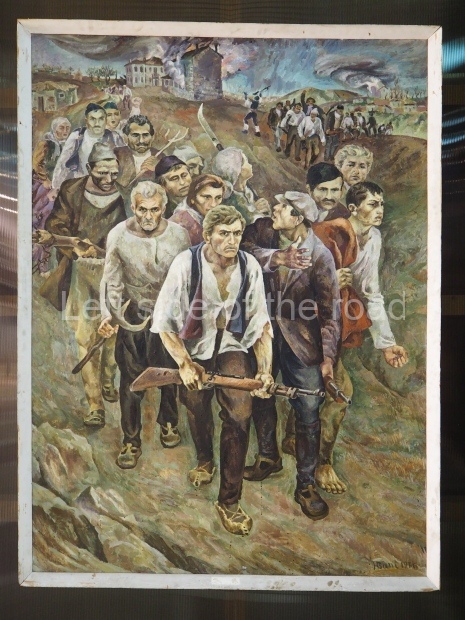

As part of this celebration there was a small exhibition of Socialist Realist Art in the entrance to the theatre – examples which are included in the slide show below. Some of these had been brought down from the Museum in the Castle for the occasion – and can be seen in the badly maintained and positively dirty museum at present. Others seems to have come from storage – as was the picture of Persefoni and Bule, the two so-called ‘Hanged Women of Gjirokaster’, two young, Partisan women, in their early twenties, who were publicly hung in the main square in the old town on July 17th 1944. This particular picture has been added as an update to the post on these two brave young Communist fighters.

Also in exhibition was a brand new, and very fine, tapestry of the Liberation which, I assume, was made specifically for the 75th Anniversary. The artist has signed their name SC – but I have no further information to date.

Update on the cemetery

I took the opportunity of a quiet moment to have another visit to the cemetery to try to get an idea of what the Anti-Fascist National Liberation war was all about. I had missed them in the past but was slightly surprised to see that (although there are many young people remembered on the tombs) there were two children of 14 (Sulo Hysi (1929-1943) and Kristo Cavo (1929-1943)) and one 16 year-old (Celo Sinani (1928-1944)) who also fell in the struggle for liberation.

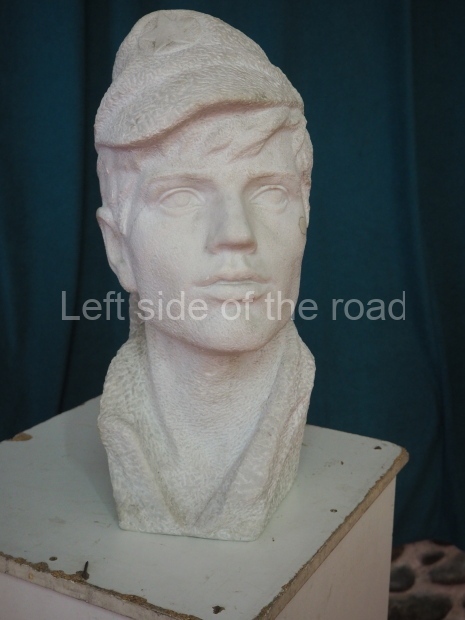

I have been having difficulty in tracking down someone in Gjirokaster who might know exactly who is represented amongst the eight heads which are depicted on the lapidar. In the cemetery there are a few tombstones which carry a red star as well as the name of the individual. These will be officially Heroes of the People. Two of those, Bule Naipi (1922-1944) and Persefoni Koadhima (1923-1944) are the so-called ‘Hanged Women of Gjirokaster’ and are the young female faces on the lapidar.

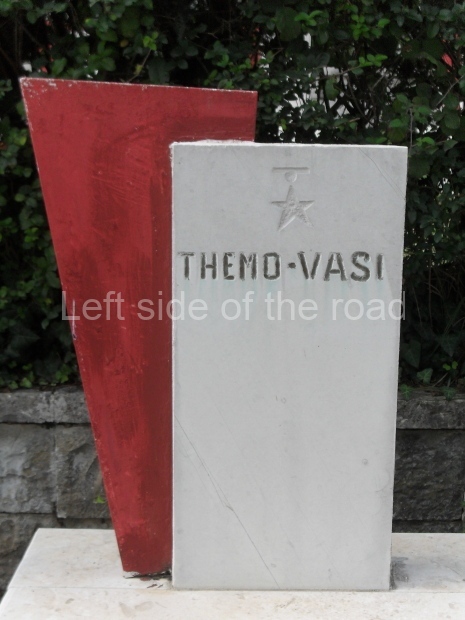

I am assuming that of the other Heroes of the People whose tombs are in the Martyrs’ Cemetery – Themo-Vasi (no dates), Celo Sinani (1928-1944) and Muzafer Asqueria (1918-1942) – might well be also depicted on the panel but if so I’m not sure which they are.

More on Albania …..