Edzna – Campeche

Location

This site is situated barely 60 km south-east of the city of Campeche, on the road to China, Pocyaxum, Nohacal and Nohyaxche. The archaeological area extends across the northern part of a broad valley in the shape of a horseshoe, with the open section in the south. Several floodable areas were modified before the Common Era, when dams, embankments and wide canals several kilometres in length were built as part of a system of hydraulic works. The present-day name was probably coined in the Postclassic as a reference to a ruling lineage: the Itzas. The actual place name may have been Ytzna, Ytz, to refer to the Itzas, Na, house, ‘house of the Itzas’. During the Classic period (AD 250-900) the city had its own emblem glyph and also used another hieroglyph to identify the territory under its control.

Pre-Hispanic history

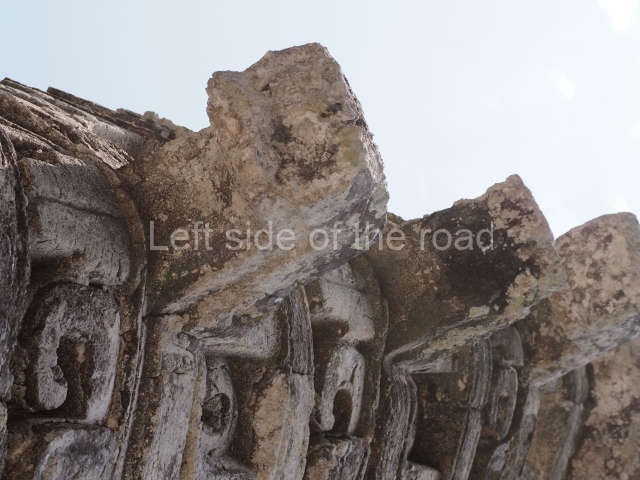

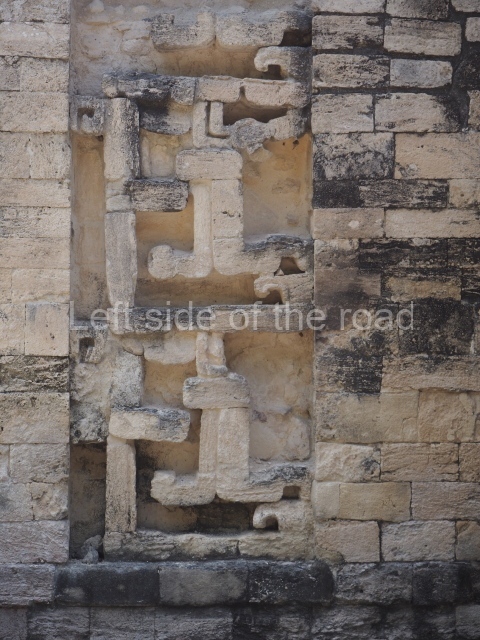

The earliest findings date from 600 BC and the preHispanic occupation ended around 1450. This timeline is documented by the ceramics, architecture and sculpture. Towards 600 BC, a small farming community laid down the foundations for a settlement that would gain masonry buildings a few centuries later. The political and social organisation permitted the development of a society governed by a small group of families who professed to have ties with the ancestors and gods. The orderly division of labour led to the construction of efficient hydraulic works that drained large sections of the valley, subsequently used for residential purposes, and generated farming surpluses. The earliest monumental architecture recorded at Edzna is of the Peten variety, which flourished simultaneously throughout the Yucatan Peninsula and the north of Guatemala and Belize. The images of the rulers were represented on stelae, tablets and altars, often incorporating dates, names and important events. Around AD 550 the method of construction began to change, giving rise to buildings with larger interior spaces and more carefully cut veneer stones, which we now identify with the Puuc style. Almost at the same time, buildings with features now known to be typical of Chenes architecture also emerged. These works were replaced around AD 950 by constructions that denoted a new era in which the Chontals appear to have played an important role. The final centuries of occupation witnessed expansions to the principal constructions, with the new wings borrowing materials from abandoned buildings. This architecture is known as Late or Postclassic.

Site description

Situated in the core area of the settlement is a large plaza measuring approximately 16,000 sq m and aligned with the cardinal points. On the north side stands the Platform of the Knives; the west is bounded by the Nohoch Na (‘Great House’); the Ball Court and South Temple occupy the south side; and the east side is taken up by the Great Acropolis, an architectural mass measuring 160 x 160 m and standing 6 m high. Other monumental structures stand on top of it. Nearby lie 20 or so large architectural groups, mainly covered by vegetation. The most important of them are the Fortress, just south of the Great Acropolis, groups 2, 3 and 4, north of it, and the Old Sorceress Group, which has been partly excavated and restored. Explorations of the constructions have revealed that the builders aligned the axes of symmetry with astronomical phenomena and used modules or average measurements, especially multiples of 20, such as 80 m and 160 m. This practice, common in the Maya region, was previously used by the Olmecs and in other societies in ancient Mexico.

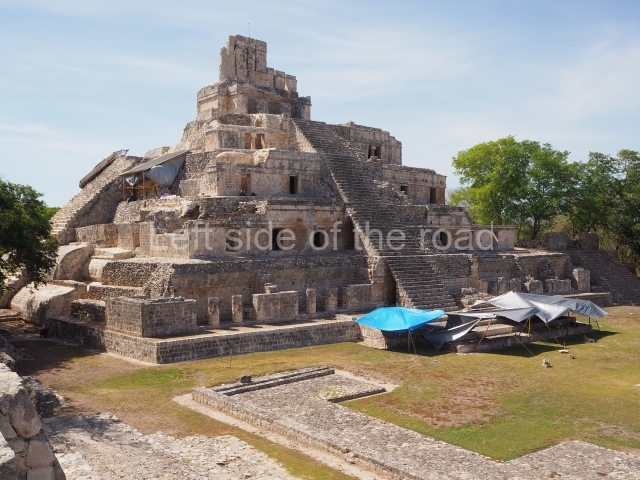

Great acropolis.

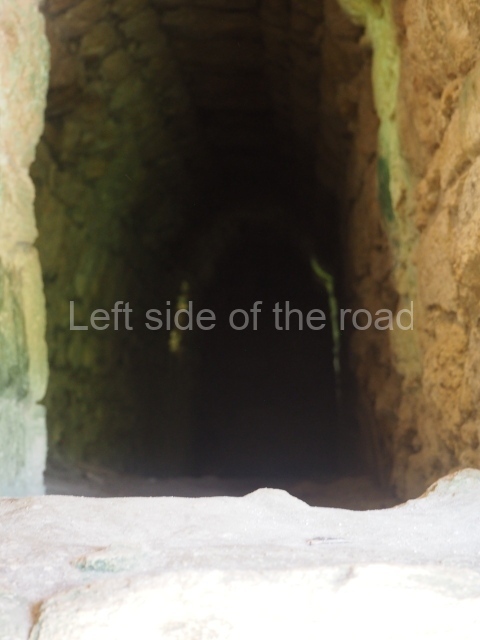

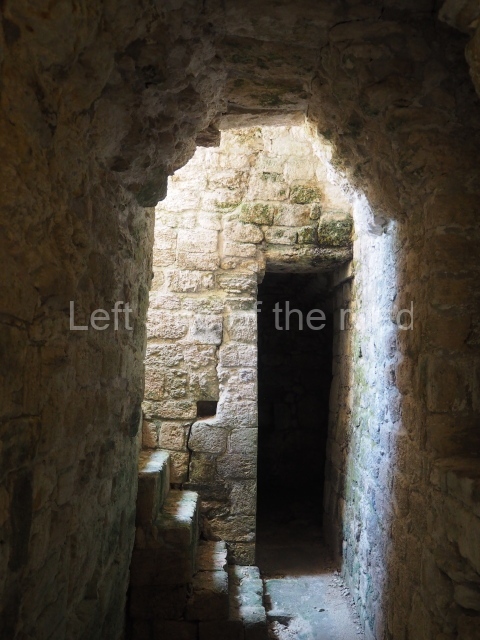

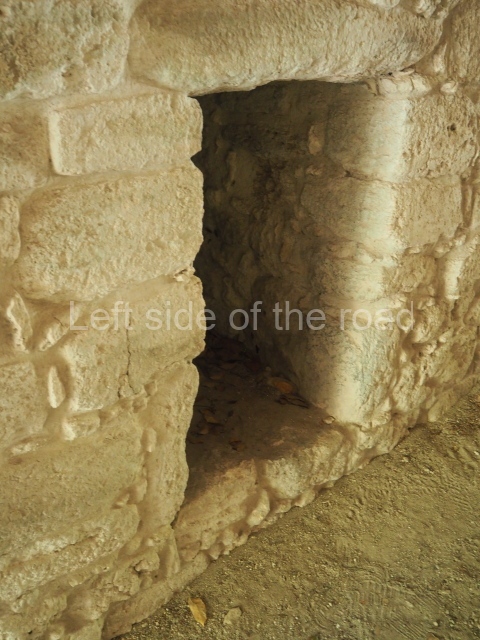

This is the result of the efforts of many generations of Maya labourers. The earliest buildings, now buried beneath later constructions, were erected just before the Common Era. The main buildings on the Great Acropolis today are the Temple of Five Storeys, the North Temple, the House of the Moon, and the South-West and North-West Temples. All these buildings had religious and ceremonial functions, although during the end of the Classic period and in the Postclassic there were probably elite residences on the west side of Five Storeys. Other spaces that were important in the daily life of the people associated with the government can be seen in the Puuc Courtyard, in the north-west section of the complex. The main entrance to the Great Acropolis is on the west side, where a stairway composed of large stone steps requires a certain effort to reach the top. Just below the upper courtyard, on the left or north side, is a small square-shaped entrance that led to a steam bath or pibna (temazcal in Central Mexico). This probably corresponds to the Postclassic, although one of the jambstones bears a fragment of an inscription from the Classic period.

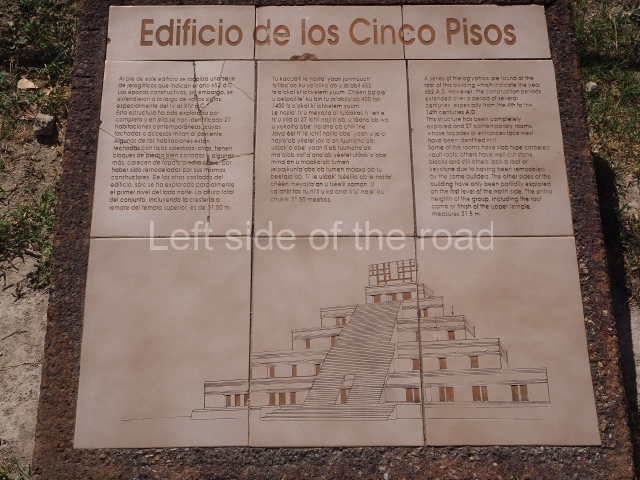

Temple of the five storeys.

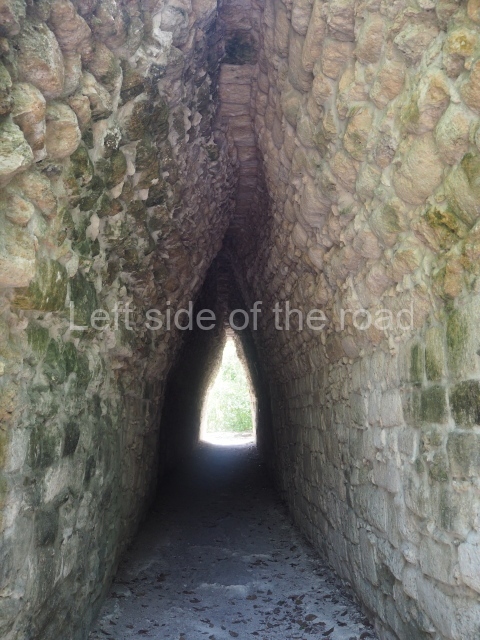

The clearest example of gradual expansion is the Peten pyramid platform nowadays partly covered by this building. On its east side it had nine sections crowned by a temple. In the middle, flanking the central stairway, are convex taludes or slopes, which can also be seen on the north side. These are the mouldings corresponding to the platform sections. In Peten times (the early centuries before the Common Era) ‘apron’ mouldings were ypically used, like the ones that can be seen in the lower sections of the east side and on certain recessed parts of the upper sections on the north side. Around the 9th century these mouldings were covered by better-cut and better-assembled blocks, with less use of wedges but creating a wide curve to achieve the type of enormous balustrades which to date have only been found at Edzna. The five-storey construction with corbel vaulted rooms on the west side of the building also corresponds to the Terminal Classic (AD 900-1000). Viewed in all their detail, the differences reveal a combination of Puuc and Chenes features. The lower part of the stairway is also an addition, made from recycled blocks with hieroglyphics that once formed part of two Peten stairways. The fifth level is occupied by a temple which had a tall roof comb, part of which can still be seen today; it once had painted stucco pieces but these have all but disappeared. Not counting the temple, the west side of the building comprises 20 rooms that may have been dwellings for officials. This elite residential complex is similar to the ones that have been reported at other Maya cities in the peninsula, such as the Acropolis at Ek’ Balam and the ‘palaces’ at Santa Rosa Xtampak, Xkipche, Labna and Sayil.

Solar platform.

This stands opposite the west facade of the Temple of Five Storeys, almost at the very centre of the plaza. Used for observing astronomical phenomena in the east and west, it shares the same east-west orientation as the Temple of Five Storeys, the Nochoch Na and Structure 501.

North temple.

This defines the north side of the courtyard. Construction commenced at the beginning of the Common Era but it was subsequently modified on several occasions. Nowadays, we can see a mixture of Peten features at the base, stairways with balustrades leading to small shrines, emulating Rio Bee architecture, recessed panels with Puuc-style veneer stones, and capstones and the foundations of temples at the top, from the Postclassic period.

North-west temple.

Situated west of the North Temple stands a pyramid platform with several tiers, crowned by three rooms. The top of the platform leads down to the Puuc Courtyard, a space defined by the west side of the North Temple and by other low constructions with rooms, in the manner of a palace. Between the North Platform and the Solar Platform lie the ruins of a low, C-shaped platform that bears no relation or symmetry to the surrounding architecture. It was built in the Postclassic for residential purposes and is made out of recycled materials from constructions that had either collapsed or been abandoned.

House of the moon.

The structure popularly known as the House of the Moon stands on the south side of the courtyard. Excavated in the 1960s by Roman Pina Chan and restored by Raul Pavon Abreu, it evokes the style of a Cubist work. Large lateral taludes or slopes were erroneously incorporated as part of the architectural restoration works, erasing the traces of several tiers. Unfortunately, it was restored at a time when little heed was paid to the evidence furnished by excavations. Nearby, to the west, is a three-tier pyramid platform surmounted by five rooms. This structure is known as the South-West Temple.

Platform of the knives.

This seals the north side of the site’s Great Plaza and has stairways on all four sides. At the east and west ends it once comprised masonry rooms in the classic Puuc style, while the middle section was subsequently used to build several smaller and poorer-quality rooms. It owes its name to the discovery of flint knives during the excavation and restoration of the east section by Pina Chan in the 1970s. The central and west sections of the platform were explored in the 1980s by Luis Millet and Heber Ojeda from the INAH.

Courtyard of the ambassadors.

Situated west of the Platform of the Knives is a small plaza, approximately 900 sq m, surrounded by low constructions, mainly from the Early and Late Postclassic (AD 1000-1250- 1450). Two buildings in the south-west section have several entrances formed by columns. South of these constructions is a partly restored ramp. South of the courtyard, behind the balustraded stairway, is what appears to be an arch but is in fact a sub-structure minus its lateral walls. The name of the courtyard was coined in the 1990s as a show of goodwill to the ambassadors of the European countries that provided funding for several excavation campaigns at Edzna with refugees from Guatemala.

Nohoch na.

The west side of the Great Plaza is dominated by this large building 135 m long, 30 m wide and 9 m high. Four long galleries on the top of the building were accessed by 12 entrances formed by masonry pilasters. It once had a vaulted ceiling but none of this has survived. It also had wide stairways (120 m long) on both sides and was possibly used for storing, exhibiting and redistributing the rulers’ wealth: farming products, textiles, animal skins, ceramics and miscellaneous utensils. The east side was excavated by Luis Millet and Florentino Garcia in the mid-1980s.

South temple.

The south side of the Great Plaza at Edzna is defined by the Ball Court and this building, a large four-tier pyramid platform in the Peten style with recesses and stone tenons at the corners. Viewed from the plaza, it is possible to see the rear section, a large talud running the entire length of the central axis of symmetry. The stairway facade constitutes the south side. The temple at the top was built between AD 600 and 800 with the carefully cut blocks typical of Puuc architecture.

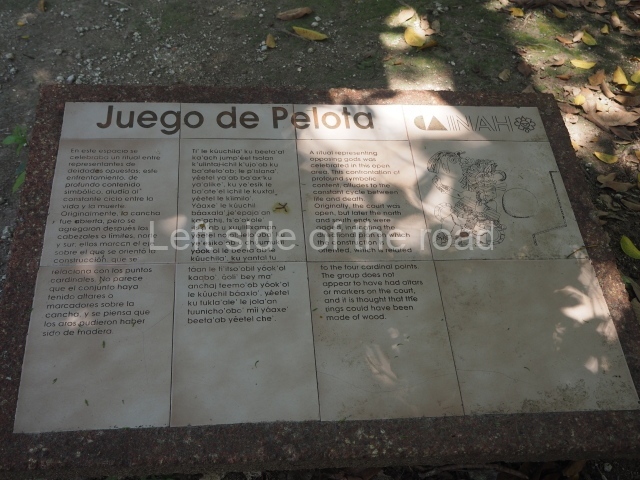

Ball court.

Like all the great regional capitals of the day, Edzna had a specific building for the practice of the life and death ritual that we now know as the ball game. The court provided a stage for the enactment of the mythical confrontation between opposing deities and essences (light and dark, east and west, etc.) and was the focal point around which daily life revolved. It was not so much a sport as the celebration of a constant cycle of renewal. The axis of the Ball Court runs north-south and displays the veneer stones typical of Puuc architecture. Embedded into the vertical walls, on both slopes, are small fragments of the stone rings. In terms of its size, the court is comparable to the one at Coba (Coba Group) and two of the courts at Chichen Itza, all of which also have a north-south axis.

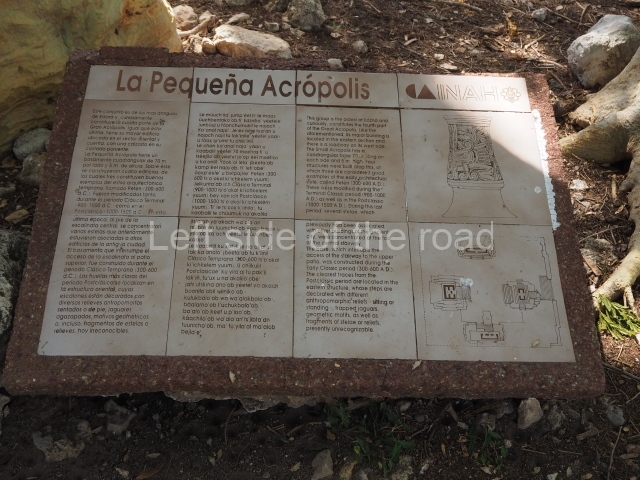

Small acropolis.

This is situated just south of the Great Acropolis but has only a quarter of the latter’s volume (70 x 70 m and 5 m high). The main entrance is situated at the middle of the west side, where the ancient Maya concentrated most of the stelae found at the site (now removed for their greater preservation and future display; some of them can be seen at the entrance to the archaeological site). Four buildings arranged around a courtyard have been excavated at the top of the acropolis. Most of the buildings have Peten sub-structures, but the builders of Postclassic times added reliefs and blocks with varying motifs to the structure on the east side to create a stairway. This explains why many of the cants display reliefs of standing or seated figures, crouched jaguars, heads and geometric and curvilinear geometric shapes.

Temple of the masks.

A large guano palm roof protects the polychrome stucco features that represent the sun god at two important moments for the preHispanic world view: dawn and dusk. The sun god is depicted with a human form and with the ornaments and accessories (ear spools, nose rings, headdresses, etc.) used by pre-Columbian dignitaries. Although framed by light blue bands, the sun god is mainly painted red, which was a sacred colour. The east side of the building displays the god of the sunrise and the west side displays the god of the sunset. These masks have been dated to the early centuries of the Common Era (Early Classic). Masks in general had been common features at numerous Maya sites since the Preclassic, nearly always flanking the stairways of temples and shrines dedicated to K’inich Ahau, the sun god.

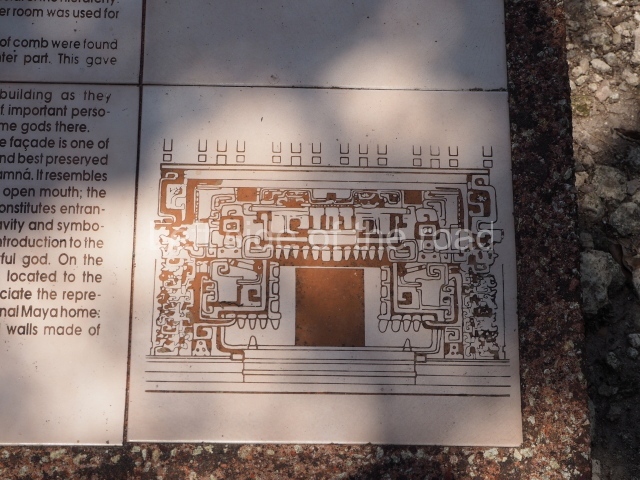

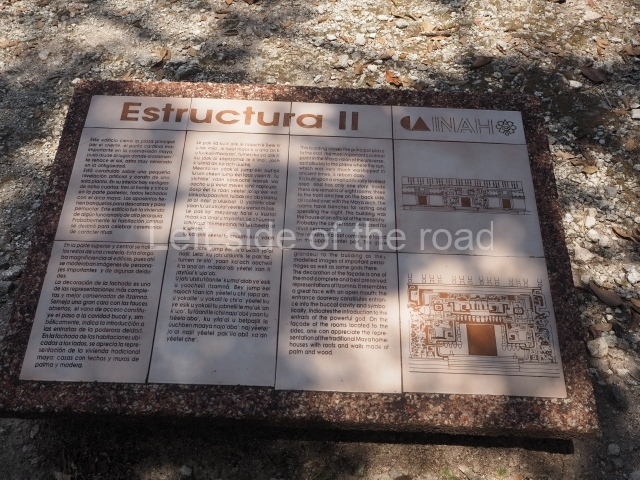

Structure 512.

This is situated north-west of the Great Plaza, on the path leading to the Old Sorceress Group. Its architecture is reminiscent of Chichén Itzá, with a lower sloping wall, simple moulding and a low wall around the perimeter. This construction is unusual in that the main facade displays two drum columns and there are two monolithic columns inside. It therefore represents a combination of Puuc architecture and the Terminal Classic architecture that succeeded it. The similarity with Chichén Itzá must not be taken as proof of proliferation or conquest. The distance between the two sites as the bird flies is 210 km, a journey of 12 to 14 days by land. We believe that the similarities are due to the fact that both sites embraced the same new construction ideas that emerged in the Terminal Classic and were manifested in architecture and sculpture. As more sites in the north of the peninsula are excavated, we will surely find more similar ruins from that period, well-known already in eastern Yucatan but poorly represented in the archaeological findings in other regions.

Old sorceress group.

This is situated 800 m west of the Great Plaza. It was built in 300 or 400 BC on a large level piece of land with a surface area of nearly one hectare. Six buildings arranged around a courtyard of approximately 1,500 sq m have been recorded. The two buildings on the east side contained small spaces for rituals. A square altar stands at the centre of the courtyard. On the north and south sides are elongated mounds of rubble as yet unexplored. On the east side we can see a large pyramid platform, standing just over 20 m high; only the lower eastern section has been excavated and restored. Most of the visible buildings in this group were erected in the Peten style. The principal platform has rounded, recessed corners and a central stairway with enormous blocks of limestone. Similar elements can be seen on the stairways of the buildings on the east side.

Resting at the foot of the pyramid platform are large blocks of stone corresponding to the ‘apron’ moulding on the first tier of the construction. One of them was used at the beginning of the 20th century as a table for depositing offerings to a legendary figure. The peasants who passed by on the way to the fields would leave coins and water. On their way home, they would find food in exchange for what they had left. One day an inquisitive young boy decided to hide to see who the mysterious person was. The peasants tried to persuade him not to, but he would not listen. After a long wait, he saw an old woman, but a black dog accompanying her saw him and followed him. The boy ran home, fell seriously ill and confessed his mischief. A few days later he died and the old sorceress stopped trading with the peasants. The legend recalls an ancient Maya legend in which a woman helps people. With certain differences, the tale evokes that of the old woman of Uxmal whose dwarf son, hatched from an egg, came to rule the land. The Popol Vuh also makes reference to an old woman who looked after two twins. In short, the old sorceress and the grandmother personify the ancient moon goddess, who according to the ancient Maya helped human beings in a number of ways, being linked to weaving, predictions, medicine and childbirth. However, wrongful behaviour could cause the moon goddess to bring about floods, drowning and death.

Monuments

Thirty-two stelae or fragments have been recorded at Edzna. The earliest date is AD 652, which has been deciphered on Stela 22 and on the hieroglyphic stairway at the bottom of the west side of the Temple of Five Storeys. The latest date inscription found is AD 869 (Stela 9). Older stelae (from batkun 8) have also been found; these were probably carved in the early centuries of the Common Era but they have yet to be dated. The principal motif represented on the stelae at Edzna is the powerful ruler of the city, with rich garb and a variety of necklaces, bracelets and religious and political symbols. He is nearly always standing and usually has his eyes fixed on a space to observer’s left. His hands are only empty when he is seated on a throne. He usually carries a sceptre, a warrior’s mace (a trefoil element) or a shield. Several stelae graphically depict the victory of the ruler of Edzna standing over one or more captives either with their hands tied or in an uncomfortable position. The epigraphic and iconographic analysis conducted by Carlos Pallan Gayol (INAH) indicates that to date we have the images of at least ten rulers of the ancient Maya city, stretching from AD 633 to 869 (not including the Early Classic rulers). Future research will undoubtedly shed more light on these and other rulers of Edzna, because the ceramic and architectural timelines suggest that there were more high-ranking officials. Other stone monuments found during the excavations include lintels, serpent heads, tablets and altars. The best sculptures and some of the stelae from Edzna are exhibited at the entrance to the archaeological area.

Importance and relations

Edzna was one of the principal capitals in the western peninsula for several centuries, during the beginning of the Common Era and up to just after the 10th century. It was a contemporary of other great settlements in this part of the Maya region, such as Oxkintok, Uxmal, Jaina, Acanmul, Itzimte, Santa Rosa Xtampak, Dzibilnocac and Champoton. As time passed, the trading of products and man-made objects increased. Items made of shell and conch from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean reached Edzna. Obsidian from El Chayal, Guatemala, has also been reported, arriving throughout most of the Classic period. Other obsidian objects and various basalt and andesite objects travelled to Edzna from the Chiapas Highlands, Veracruz, Hidalgo and Michoacan. The jadeite pieces came from the River Motagua valley. Throughout the centuries, the pottery traditions also changed, giving way to vessels produced in the region and the importation of polychrome vessels and plates from Peten, the Campeche coast, Northern Yucatan and Belize.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp293-299.

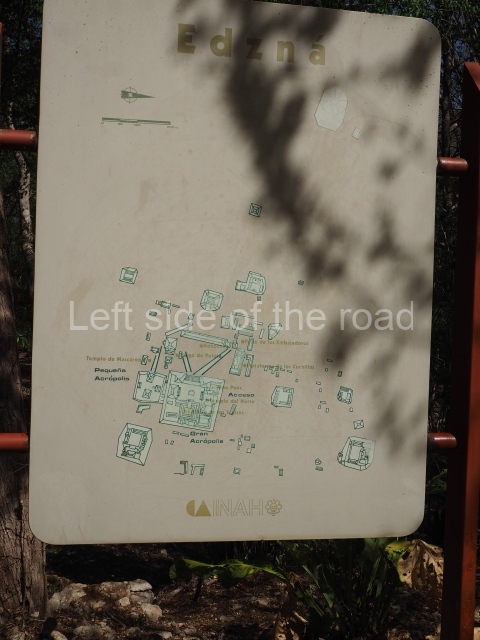

- Great Plaza; 2. Great Acropolis; 3. Temple of the Five Storeys; 4. Solar Platform; 5. North temple; 6. North-west Temple; 7. Puuc Courtyard; 8. House of the Moon; 9. Platform of the Knives; 10. Courtyard of the Ambassadors; 11. Nonoch Na; 12. South temple; 13. Ball Court; 14. Small Acropolis.

Getting there;

From Campeche. Combis leave from Calle Chihuahua, east of the main market. Actually enters the parking of the site. On the return wait for the next combi. It will take you, first, to the end of the line at Bonfil but then returns directly to Campeche, this time missing out the archaeological site. M$45 each way.

GPS:

19d 36′ 10″ N

90d 13′ 53″ W

Entrance;

M$90