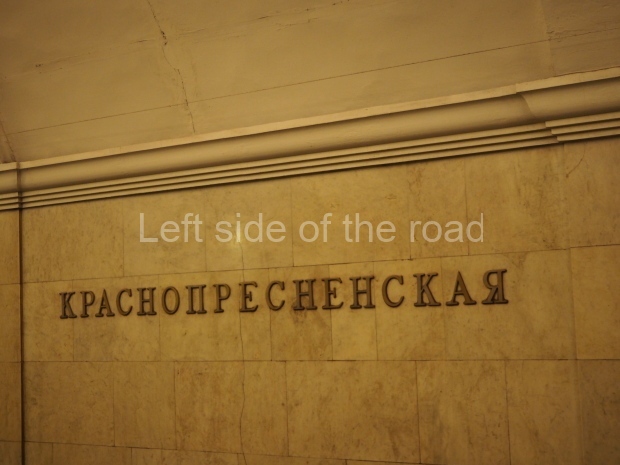

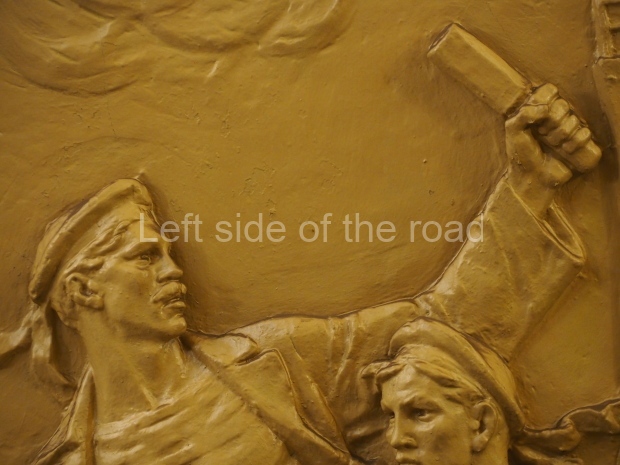

Hillsborough Memorial – LFC Anfield

More on Britain …

Symphony No 11: Hillsborough Memorial – Michael Nyman

Symphony No 11: Hillsborough Memorial – Michael Nyman, was composed in homage to those 96 Liverpool football fans who were killed as a result of ‘the corruption of the Thatcher government and her duplicitous police force’ during the FA Cup semi-final match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at Hillsborough, the home ground of Sheffield Wednesday, on 15th April 1989. It was chosen as the cultural performance to officially launch the 8th Liverpool Biennial 2014 – the city-wide celebration of contemporary art that will run this year between 5th July to 26th October.

This public performance on the Saturday evening in Liverpool Anglican Cathedral was preceded earlier in the afternoon by a performance to invited guests, including representatives of the families of the 96.

The Symphony, which lasts for about 50 minutes, is divided into four movements.

The First Movement consists of the reading of all the names of the 96 killed that day, now more than 25 years ago. This reading of the names has become a tradition at any commemoration of the event, especially that which takes place every year on the anniversary at Anfield, the home of Liverpool Football Club.

This must be highly emotional in any circumstance but when the names were sung by Kathryn Rudge, a mezzo-soprano, standing in the pulpit of one of the top 5 biggest cathedrals in the world (depending upon how the statistics are measured), her voice reverberating around the huge space, this rendering of the traditional practice took on a greater poignancy – each person listening being able to relate to any death that might have effected them in the past. For close family members it must have been very difficult.

As the names were being sung the orchestra, mainly the strings, were intoning a slow, repetitive rhythm, typical of many of Nyman’s works, which got louder as more instruments joined in and reaching a crescendo as the last name, in alphabetical order, was read out.

The Second Movement is more lyrical and is based on an aria that Nyman had previously rejected for one of his earlier operas. This breaks, slightly, the sombre mood created by the reading of the names and turns more into a celebration of those lives that were prematurely cut short. The violins are lighter in tone and their pace quickens. The older children of the Liverpool Philharmonic Youth and Training Choirs vocalise and their young voices have the effect of adding to the lightening of the tone. When the other instruments, especially the brass, are added to the mix the sound of the orchestra seems to fill the cavernous space and the movement ends in an affirmation of life – of those who had died and of life in general that goes on, even after a major disaster.

For Nyman, the composer and mathematician (as all composers are in many senses), the Third Movement is all about numeric symbolism, a play on the number 96 – different combinations of bar phrases and chords. That means nothing to me (my technical musical knowledge amounts to zero) but I feel it takes the different elements and emotions from the first two movements and plays them together, sometimes a battle between the sombre and the more cheerful.

The movement starts with the bassoons and deep-toned brass instruments introducing the theme called Memorial (the name of the Fourth Movement). When the theme is introduced it is played very slowly and deliberately but this is soon left behind as the rest of the orchestra, and the choir, join in. The first part of the movement is the domain of the bass and the larger stringed instruments, with the violins being virtually silent. However, slowly the rest of the orchestra joins in and the mood lightens and the pace quickens.

The violins pick up a repetitive phrase that they continue to play, with slight variations being introduced at times, as their pace quickens and gives the impression of flight. This part of the movement has more elements of life than death and the players have to be more animated to keep pace with the notes on the page.

The brass and the woodwind sections join in and the sound again starts to fill the Cathedral space, reaching a crescendo but not a movement ending crescendo, more the sound comes as if in waves, building up and then quietening to gather pace and volume once more.

Just before the end of the movement the players slow down and the full children’s choir takes over as they again vocalise until the full orchestra again takes control and speeds up yet again to end the movement on a high note.

If the first three movements are new, or at least re-workings of previous material, the Fourth Movement would be recognised by anyone who is, or was, a fan of 1980s British art house cinema as Memorial (as this movement is known) was part of the soundtrack for the 1989 Peter Greenaway film The Cook, the Thief, his Wife and her Lover.

However, the piece goes back even further than that and, coincidentally, involves another footballing disaster and Liverpool FC. Memorial was Nyman’s response to the Heysel stadium disaster where, due to the poor crowd control arrangements, a surge of Liverpool fans led to the death of 41 Juventus supporters – it’s unfortunate that two of the most serious football catastrophes of the 1980s concerned Liverpool, although as time goes by it emerges that the fans themselves were not those principally to blame for how events developed.

It was never publicly performed but Greenaway considered it perfect for his 1989 film about a brutal and uncouth gangster. The story was generally considered to be a modern-day fable, paralleling the accumulation of wealth by culturally ignorant barrow-boys in the City of London during the hideous Thatcher era to the pretensions of a violent criminal who thought that wealth bought sophistication. Here Greenaway does the same with Thatcher as Bertolt Brecht did with Hitler in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, comparing the individuals, their policies and the consequences of such policies upon the majority of the population to that of vicious, self-seeking criminals

In this film the gangster, Spica, gets his comeuppance and it’s during this particular scene that we hear a large section of Memorial. Somewhat surprisingly, to me, in a very recent interview Nyman states that he thought the use of this piece of music and its juxtaposition with the images of cannibalism ‘totally loathsome’.

I knew they had fallen out but Nyman is being disingenuous to be so angry about the use of his music by a director he had been working with since 1982 (on The Draughtsman’s Contract). If he was so disgusted why did they work together in the 1993 on The Baby of Mâcon, another allegory, this time about the exploitation of women and children?

The Fourth Movement is loud and strident from the beginning. It does get louder but there’s no gradual rise to a crescendo as in the previous movements. And that’s as it should be. We have had the statement of the crime, the sadness it had caused and the waste of life involved. Now it has to be brought to some sort of conclusion, the demand for justice against all the years of lies and, yes, some sort of retribution.

From the beginning the violins are played in a choppy, staccato manner (there’s probably a term for it but unknown to me) and this rhythm is in the background for virtually the whole of the 12 minutes or so of the piece. It’s almost like a sound of the tramping of feet, of people marching which is more than appropriate when we consider that at the time of the premier the re-called inquest into the deaths of the 96 was taking place only a few miles down the road in Warrington.

This is a valid interpretation even for a piece that was written almost 30 years before. Nyman has chosen to take it from the past and placed his music into a ‘story’ that cries out for resolution. The brass section blows out a call to arms, to action, for justice. This is strident, angry music reflecting the feelings not only of the families of the 96 victims of Hillsborough but of many in Liverpool, as well as many thousands of football fans throughout the country, who consider they are often being made scapegoats for the inefficiencies and inequities of the society in which we live.

Pain and anger can’t be expressed by sweet pastoral music that lulls the listener to sleep. The meek only inherit the earth in that they are forced to eat dirt, martyrs who refuse to resist their oppressors will only end up crucified on the cross, the symbol at the far end of the building and which all in the audience were facing at Liverpool Cathedral.

If the families of the 96 had submitted meekly history would have recorded that they were responsible for their own deaths and the cause of the disaster, the real guilty going free. Now, with the new inquest and whatever comes of it, there’s no guarantee that those responsible will ever pay for their crimes (of lying if not for incompetence) and that will mean many people will remain angry but that’s better than regretting not having struggled in the first place.

By the end all the players are performing, as are the children in the choir and the mezzo-soprano, all adding their weight behind the call. Eight or nine minutes in the sound becomes more discordant depicting anger and pain. You can almost hear the cries of those trapped behind the reinforced steel fences introduced as a knee-jerk reaction to pitch invasions – without thinking of or taking into account the possible consequences. If the movement was already strident perhaps the one change I was able to notice was the crash of cymbals and the beating of the kettle drums at the very end. The music finishes with a further call to mobilisation.

I don’t know if it was just due to the fact that the Philharmonic Hall is currently undergoing major renovation that the Cathedral was chosen for this performance, or whether it would have been performed there whatever the situation of the orchestra’s normal home. It can only be said that attending this performance in the cavern that is the Liverpool Cathedral was the best choice. For those with a religious bent there’s the obvious symbolism that goes with the Christian penchant for pain and suffering, for those who are not so inclined being surrounded by sound in such a large space made it an unforgettable experience.

A recording of the Symphony has been made and will be played in the Liverpool Anglican Cathedral on Wednesday 6th August, Monday 26th August, Wednesday 3rd September and Wednesday 17th September. All performances will start at 15.06 – the time when the match was stopped on 15th April 1989.

Symphony No 11: Hillsborough Memorial – Michael Nyman is a fitting memorial to those who died so needlessly 25 years ago and also a fine way to open the 2014 Liverpool Biennial. I only hope that the next ten weeks provide experiences of such calibre.

More on Britain …

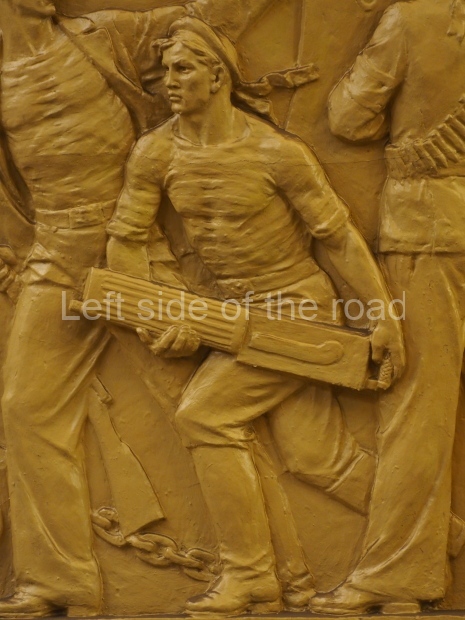

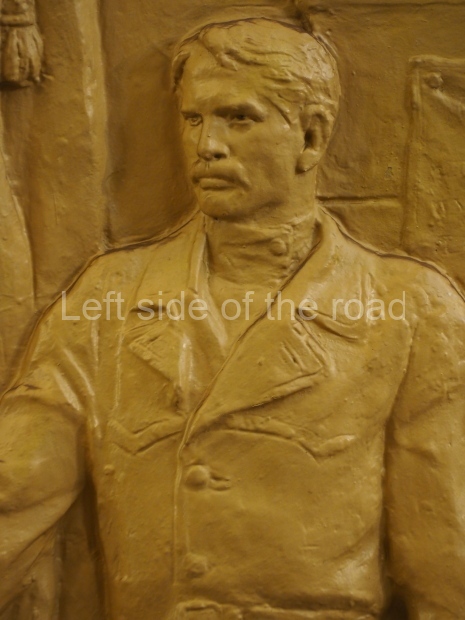

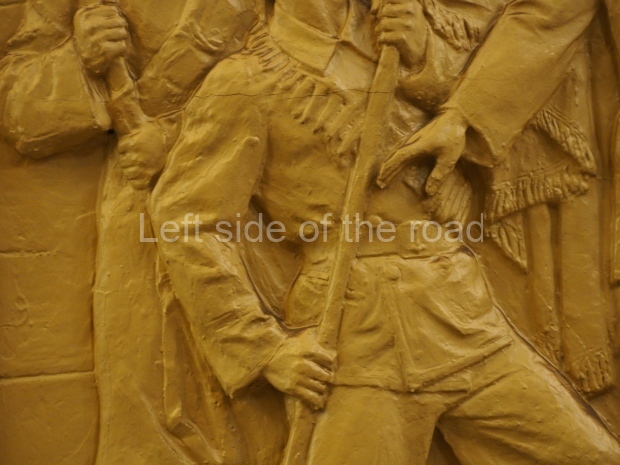

Hillsborough Memorial Sudley