More on the Maya

Xcaret – Quintana Roo

Location

This is situated on the coast, on a steep cliff composed of a fossil reef overlooking a tiny cove which in ancient times may well have been a port and shelter for sailing vessels. Nowadays, the archaeological site has been absorbed into a theme park. From Cancun, take federal 307 to Tulum in the south and the turn-off to Xcaret is 7 km after the town of Playa del Carmen. The archaeological area is inside the Xcaret Park.

History of the explorations

Herbert Spinden and Gregory Mason first reported the site in 1926. In the 1940s, the explorer and photographer Loring M. Hewen visited Xcaret accompanied by the archaeologist E. W. Andrews IV. The latter returned in 1956 to undertake research at the site. In the 1970s, Anthony P. Andrews continued and supplemented the work begun by his father. In the 1980s and 1990s, Maria Jose Con Uribe of the INAH led a new research project at Xcaret aimed at delimiting and mapping the site, as well as excavating and consolidating the buildings. Nowadays, Xcaret has been transformed into a theme park incorporating the archaeological area.

Pre-Hispanic history

We do not know the origin or meaning of the name Xcaret, but we do know that in pre-Hispanic and colonial times it was called P’ole, derived from the root p’oi, meaning merchandise, dealings and contract with traders. The Chilam Balam de Chumayel refers to Pole as the first point where the Izta stopped en route to Chichen Itza. It is also referred to as the point of departure for pilgrimages to worship the goddess Ixchel on the island of Cozumel. The present-day name would appear to be a corruption of the Spanish word caleta, meaning cove.

The earliest human settlement dates back to the Late Preclassic, denoted by a few ceramic fragments and several low platforms. At that time, there were various fishing villages and farming communities along the coast. A population increase appears to have occurred in the Late Classic, although the site experienced its heyday in the Postclassic. The architecture of the large platforms with rounded corners, combined with the presence of ceramic traditions from the north of the peninsula, suggest a cultural development highly typical of coastal sites. Meanwhile, the presence of various types of polychromy and objects of jade, obsidian and quartz indicate close ties with sites in the central Maya area, such as the Guatemalan uplands. Although the site was relatively insignificant during the Classic period, it nevertheless shows a well developed political, economic and social organisation.

The population increase occurred in the Postclassic, when like other sites along the coast the city gained in importance, principally by trading marine resources and taking advantage of the circumpeninsular trade network stretching as far as Honduras. Due its situation opposite the Island of Cozumel, Pole became the principal port of departure for the numerous pilgrims who sailed across the sea in canoes to the famous shrine dedicated to the goddess Ixchel. During the early years of the colonial period, it remained an important port of entry and departure between the mainland and Cozumel. The runs of a small 16thcentury church date from this time.

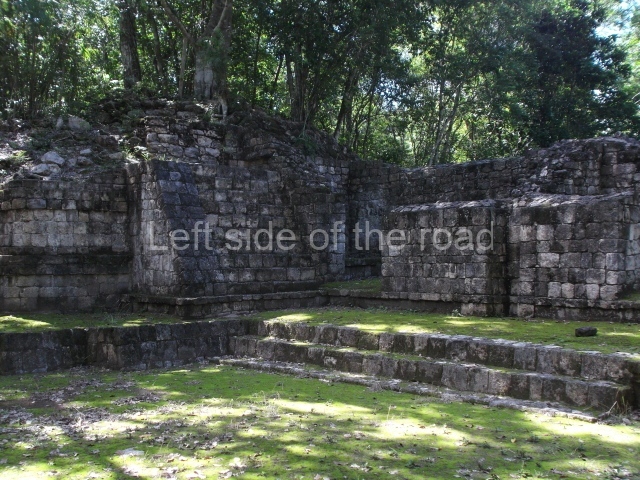

Site description

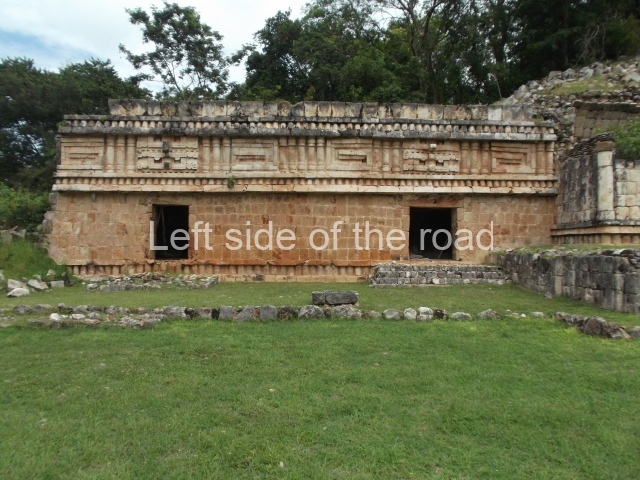

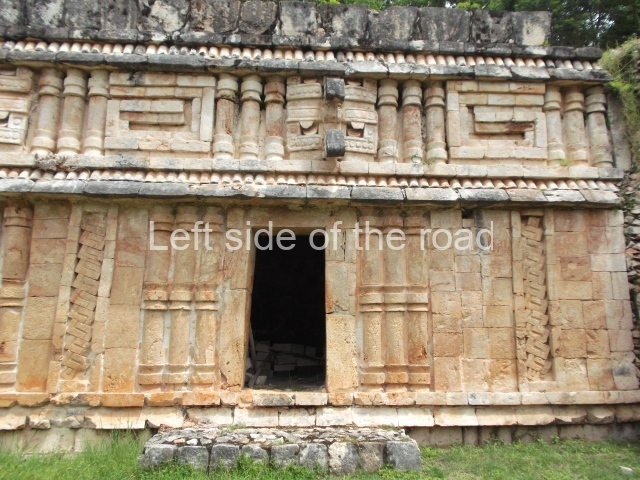

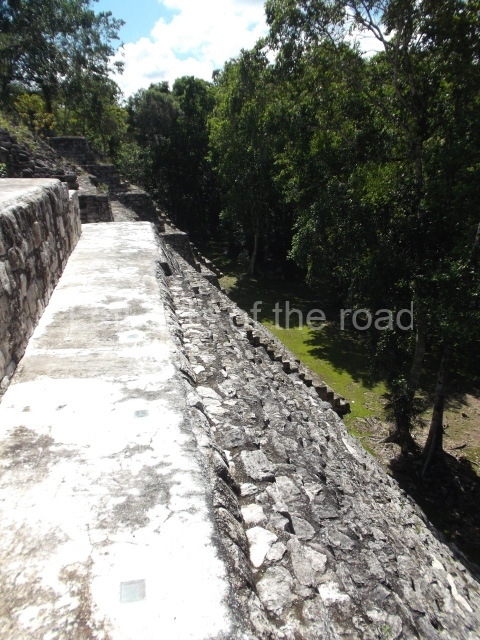

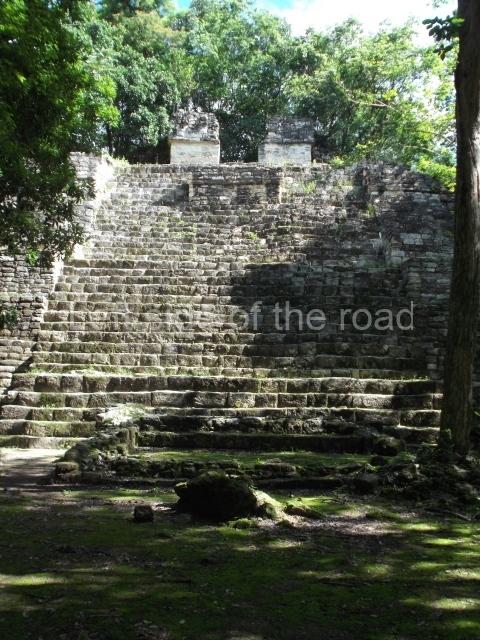

The settlement adopts a linear layout along the coast, forming groups of buildings and isolated temples on the sea shore. A wall runs parallel to the coast, separating or protecting most of these groups. The residences are situated around the site.

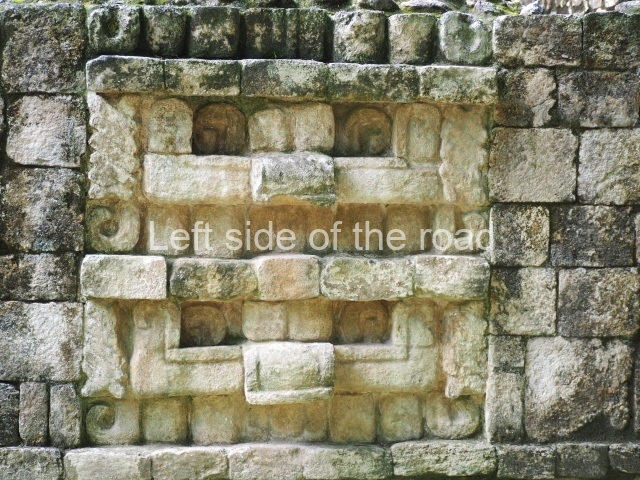

Group A.

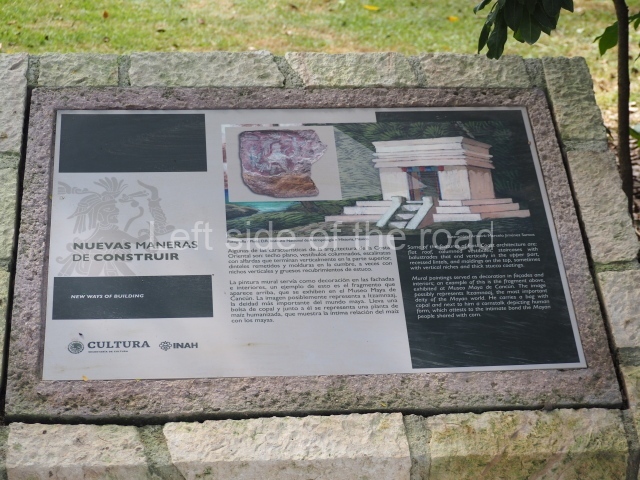

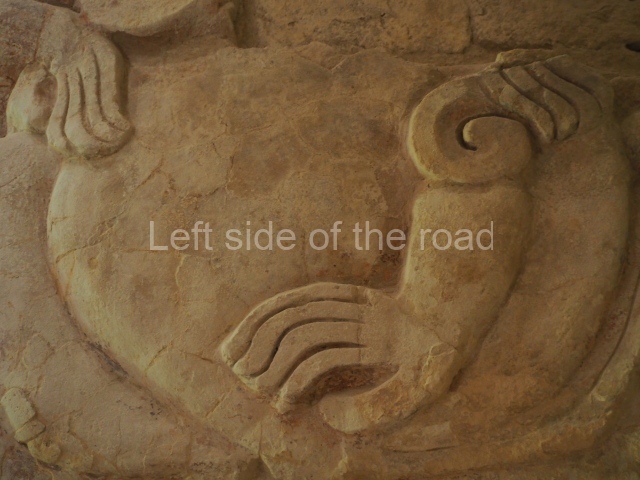

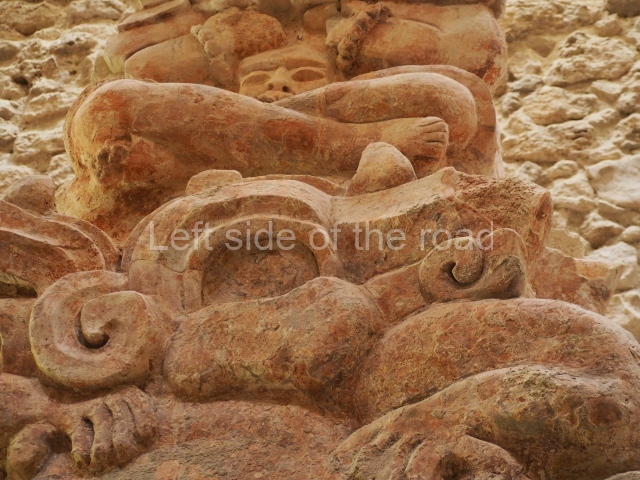

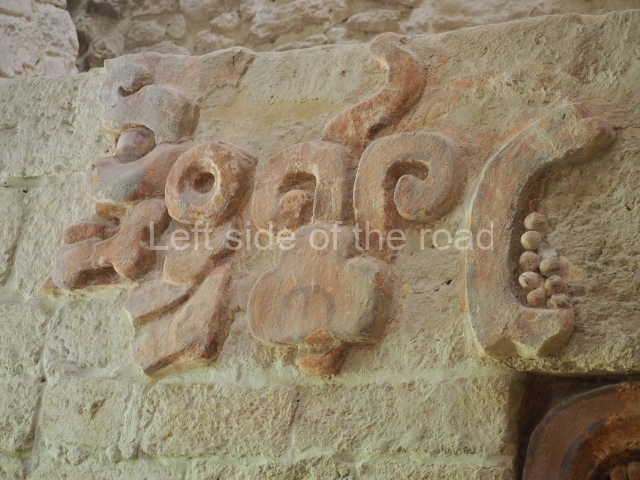

This is situated on a rocky promontory at one side of the cove, near a cenote and protected by the wall that separates it from the sea. The only entrance in the wall is situated at this point. The group consists of ten structures, nine on an artificial platform forming a plaza, and the tenth at a lower level. The constructions have a religious function and must have originally been decorated inside with bright colours and symbolic scenes. Some temples contain altars for offerings or figurines. The platform supporting the twin temples corresponds to the Classic period, which is distinguished by finer stonework and rounded corners. The remainder of the constructions in this group date from the Postclassic.

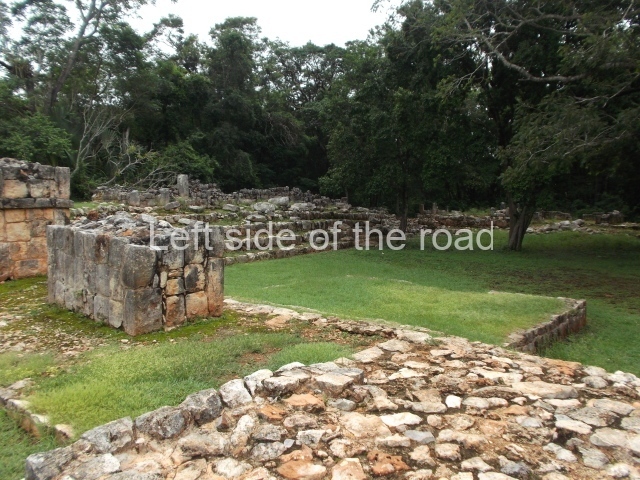

Group B.

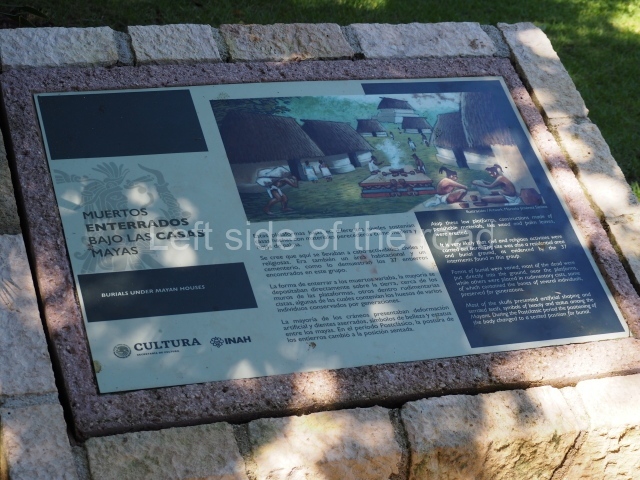

This comprises large, low platforms which form plazas and once supported wood and palm constructions. The most outstanding element of the group is Building B-3, which is composed of three inter-connecting rooms once covered by a vaulted roof. Adjoining this building is a small temple, B-2, from the Postclassic period. The remainder of the platforms, all with rounded corners, correspond to the Classic period and were used for civic and religious activities. Some of them were also used as burials for high-ranking dignitaries. The most common forms of burial were to place the individual directly in the ground or inside rudimentary cists. In most cases the individual were laid down with a plate over their faces and some form of offering. More often than not, the skulls had been subjected to cranial deformation and the teeth sawn to points. Most of the burials date from the Late Classic and a few from the Postclassic.

Group C.

This comprises low platforms, two of which were once surmounted by masonry temples. Two constructions share the same platform; one has two bays and a colonnaded entrance. Four structures connected by a low wall form a closed precinct around an altar. Some structures show at least two construction phases and functions, being used initially as a dwelling and then as a burial. The structure at the north end of the group contained the tomb of several individuals and an offering comprising ceramic vessels. The entire group seems to have been built and used during the Postclassic.

Group D.

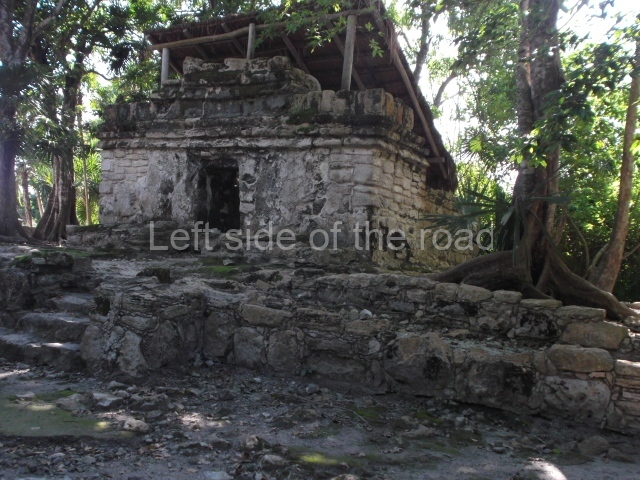

This is situated on the edge of a small cliff, adjacent to the outer wall. The main structure is a three-tier circular volume with a Postclassic temple at the top. Part of an earlier construction (Late Classic) has been exposed. Situated to one side, a small temple, now minus its flat roof and part of its walls, complements the group.

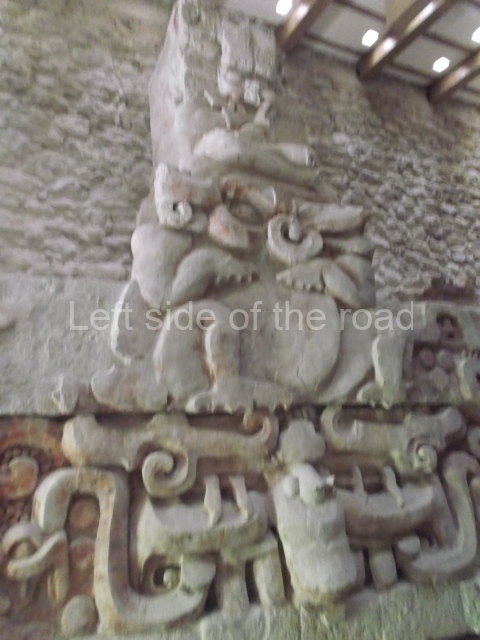

Group E.

This is one of the most important groups at the site and contains the tallest structures. Three of its buildings are connected by a wall, which disappears a few metres further north. The excavations have confirmed that the group was built during the Early Classic because older constructions were found beneath the two tallest buildings, accompanied by objects made of shell, conch, jadeite, obsidian, etc. Both structures E-3 and E-4 adopt a circular plan, although in the former case the front was subsequently modified to make it look square. The small temple at the top of Structure E-4 was also circular, with an apse-shaped room inside and a flat roof. By contrast, the temple at the top of E-3 is square-plan. The remainder of the buildings (E-l, E-5 and E-6) are from the Late Postclassic. Structure E-6 is of particular note in that it consists of a double temple – a small adoratorium inside another – and its interior and exterior walls were painted in bright colours.

Group F.

This consists of three structures on a platform with a double balustraded stairway culminating in finial blocks. The main temple is among the largest found at Xcaret and contains a great altar or throne. Its roof was vaulted and the interior and exterior walls painted blue, red and orange. The small temples next to it are from a later period. This group is situated a few metres from the Spanish church, and materials from the colonial period were found nearby.

Group G.

This small church dates from the 16th century and consists of a nave, semicircular apse and three altars: one in the middle, one at the side and one at the rear. It is oriented east-west and is accessed by three flights of steps on the north, south and west sides. It is surrounded by an atrium wall. The roof was made of wood and palm leaves. The church nave was used as a place of burial and over 150 individuals have been found there. The church is one of the earliest Spanish constructions found on the east coast.

Group H.

This is one of the finest examples of the isolated coastal temples that can be found all along the east coast. It offers a clear view of the island of Cozumel and was a landmark for Maya seafarers. It stands on a platform that once had a stairway at the front.

Ceramics

Yum Kax Group (AD 250-600).

This group emerged at the beginning at the Early Classic, when the site is known to have maintained ties with other regions in the Maya area, such as northern Yucatan and the Peten-Belize region.

Ek Chuah Group (AD 600-1200).

In the Late Classic, the cultural links that Xcaret maintained with sites on the coast and further inland are reflected in the ceramic materials. During this period it traded with a number of nearby and distant settlements in the Chontalpa and Peten-Belize regions, as well as the inland of the peninsula. There are also marked ceramic influences from the Puuc region.

Ixchel Group (AD 1200-1650).

During the final stage of its cultural development, in the Postclassic, there appears to have been greater inter-regional homogeneity in terms of ceramics, complemented by colonial ceramic materials between 1528 and 1650. This confirms that during this last stage Xcaret was one of the principal coastal settlements in the region.

Maria Jose Con Uribe

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 438-440

Getting there – and getting in:

From Playa del Carmen. Take a colectivo from the centre of town which goes along the main road towards Tulum and get off at the Xcaret stop. This is a few kilometres from the park but there’s a free, shuttle bus that leaves from the underpass. Follow the directions to the shuttle. On arrival at the complicated car park of the theme park get off the shuttle head left through the car park to wards the high wall around the park and look for a very large and high gate. It is recognisable in having a huge (now ornamental) padlock. The INAH ticket office window is to the right of this gate.

I thought that the archaeological site was separate from the theme park but it is fully integrated into it and the re are four or five locations with original Mayan structures. Many of the tourists think that they are re-constructions – as is everything else in the park. You will have to be accompanied by someone from INAH. This means you get a guide but it is also restrictive in that you only have the time the guide is prepared to give you. When I visited she had to shut the ticket office and accompany me. I have no idea if anyone arrived only to find the ticket office deserted.

I assume this happens whenever anyone wants to visit only the archaeological site.

GPS:

20d 34’ 45” N

87d 07’ 10” W

Entrance:

M$90 – as I had a camera (rather than a phone) I was also charged the ‘video’ fee of M$50. And because I had a ‘guide cum chaperone’ I also gave her a tip.