Sniper – Aliya Moldagulova

Aliya Moldagulova – in Aktobe, Kazakhstan

Hero of the Soviet Union

I’d be very surprised if many of the people who fly into Aliya Moldagulova International Airport, in Aktobe, Kazakhstan are aware that the airport is named in honour of a young, female Soviet sniper, who was credited with killing dozens (I’ve seen various figures) Nazis in her short ‘career’ as a sniper before being killed herself. The airport was renamed in her honour on 28th April 2021 (which probably bears relationship to the time of the celebrations of May 9th, the final and ultimate victory over Nazi Germany).

Born in 1925 it appears her childhood was neither comfortable or stable. The suggestion that her father was some sort of ‘nobleman’ wouldn’t have helped as such a short time after the revolution many people would have still held resentments about the past society – whether those resentments and the targets were deserving or not. However, she was a true patriot and defender of the new social system and – like many hundreds of thousands of other young men and women – readily joined (aged less than 16) the Red Army following the German Nazi invasion in June 1941.

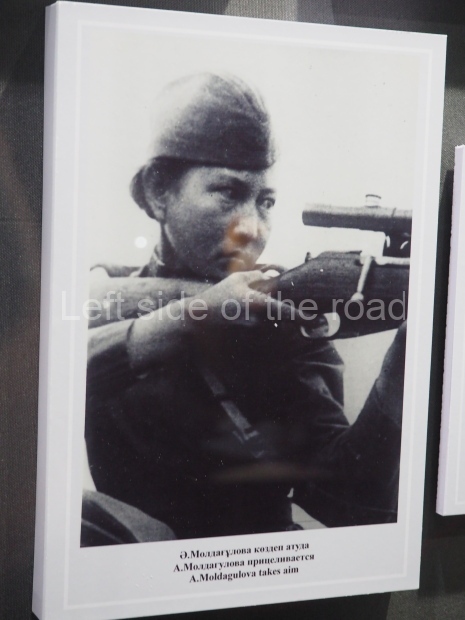

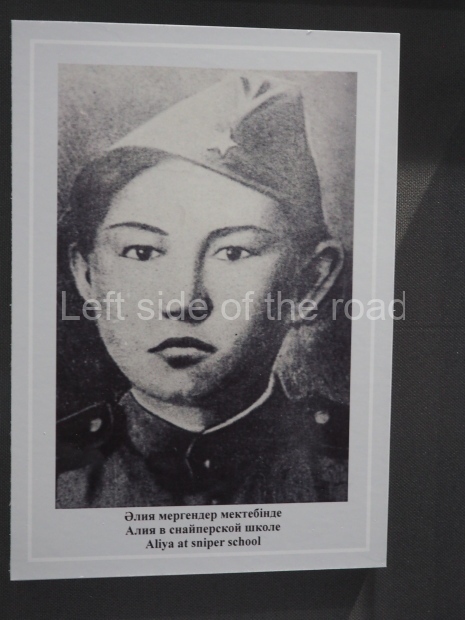

She eventually ended up in a sniper training school outside of Leningrad but her training, as far as I can see, only lasted about 8 months (from starting in the military until being assigned to the front) which seems a very short time for such a young person – even taking into account the seriousness of the situation.

She was sent to the front in August 1943 and she was dead In January 1944 – she never reached her 19th birthday. There are countess ways to condemn the futility of war – even one as existential as the Great Patriotic War – but the fact that a young woman’s life ‘achievement’ was the killing, and presumably wounding, of dozens of invading Nazis, many not much older than herself, and then to be killed after barely 5 months in battle, must be one of them.

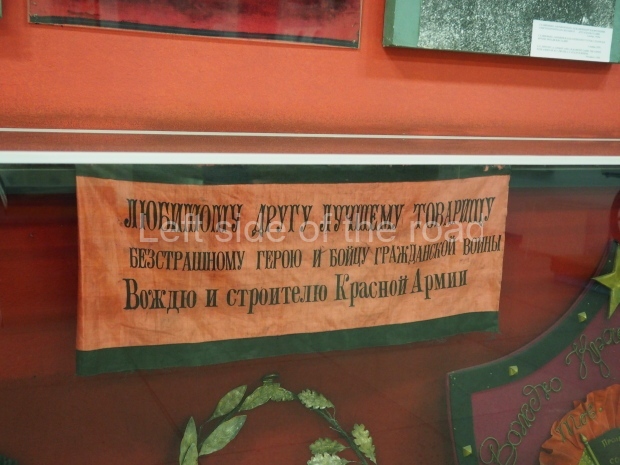

However, all armies – not just the Soviet Red Army – paid homage to those who had gone that bit further in the fight against the enemy (whether they survived the conflict or not). These men and woman in the Red Army were designated ‘Heroes of the Soviet Union’ and even though the Soviet Union no longer exists you will see busts of those so awarded throughout the territory of the former Socialist country.

Aliya is among that group of celebrated individuals in an avenue of such busts alongside the avenue, in the newer part of Aktobe, which used to bear the name of VI Lenin.

Aliya Moldagulova – In Heroes Aisle

Aliya Moldagulova Memorial Park

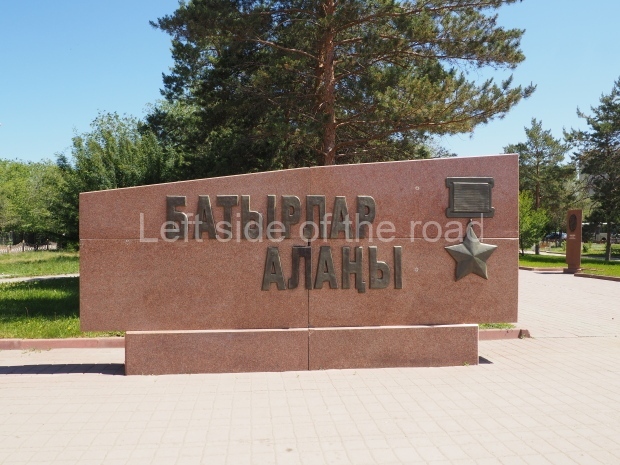

The avenue of busts leads to what is now called Aliya Moldagulova Memorial Park. (I’m not sure if in this location previously stood a statue of VI Lenin. There are no statues of Lenin on public display in 2025.)

This complex was unveiled in 2005 on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of her birth, ‘intended to appeal to be proud for our country and it’s heroes (sic)’ – according to the official visitors site.

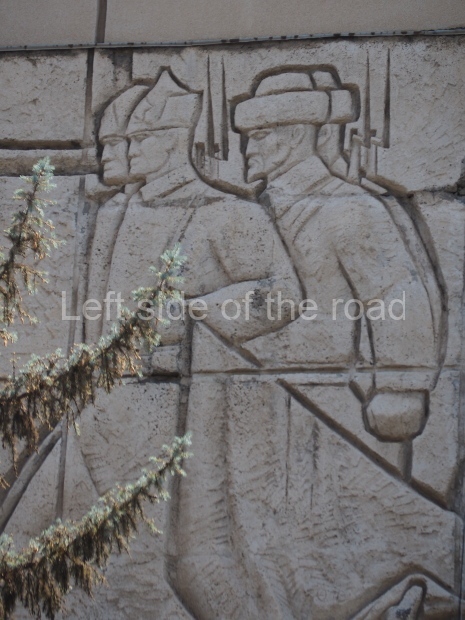

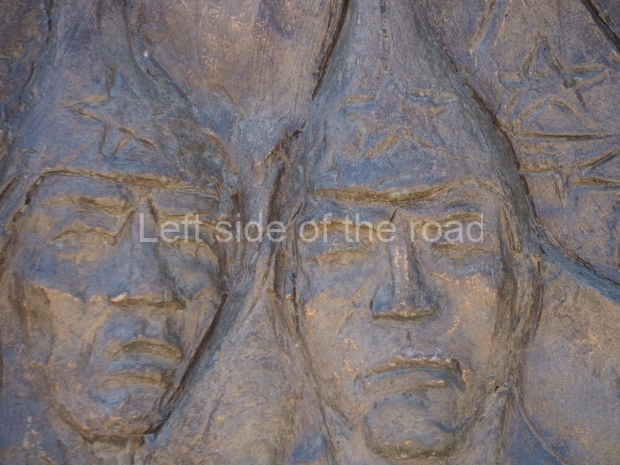

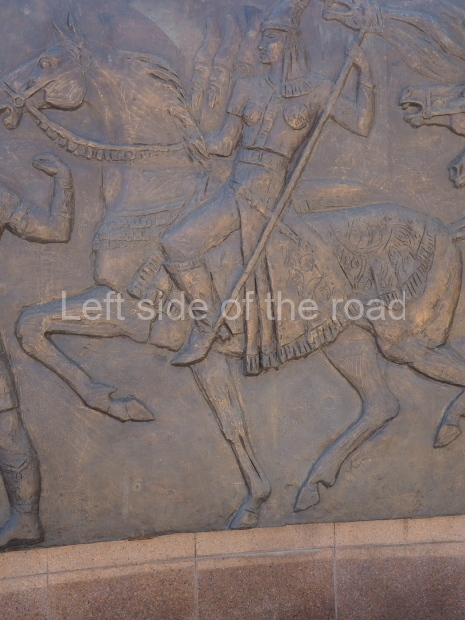

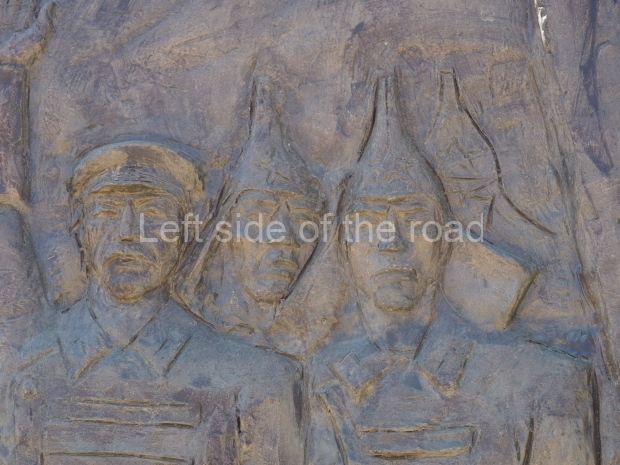

The backdrop to this complex follows very much a Soviet, Socialist Realist pattern. On the left hand side as you look at the statue, the panel represents Aktobe (and also Kazakhstan’s) past. It shows the fights for independence (against whom is not specified) including a female warrior – which sets up the scene for Aliya to be represented in the right hand panel. On this left hand side we also have the introduction of Kazakh culture in the form of a group of musicians playing traditional instruments.

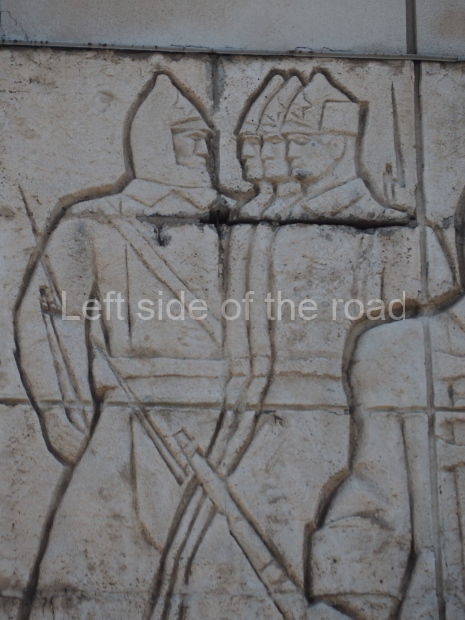

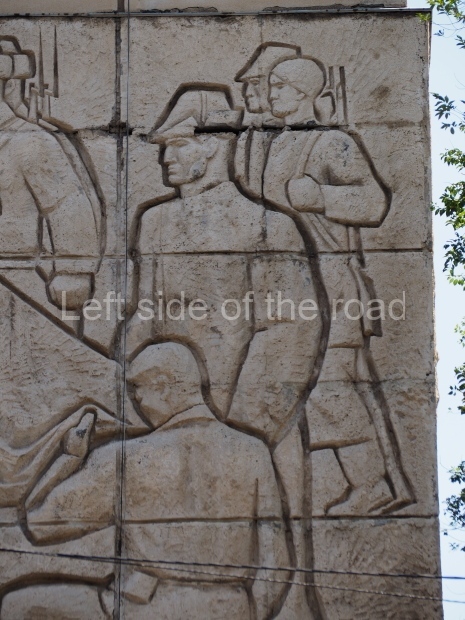

The right hand panel, however, deals with a number of specifics. On the left edge is a group of soldiers from the Civil War period when the Bolsheviks defeated the White reactionary forces, assisted by the capitalist/imperialist powers. Only when the Bolsheviks had rid their country of these elements were they able to start on the construction of Socialism. Then we have industrialisation (with the construction of dams and providing electricity to the whole country) and the collectivisation of agriculture – both of which, somewhat surprisingly, are represented in a positive manner here.

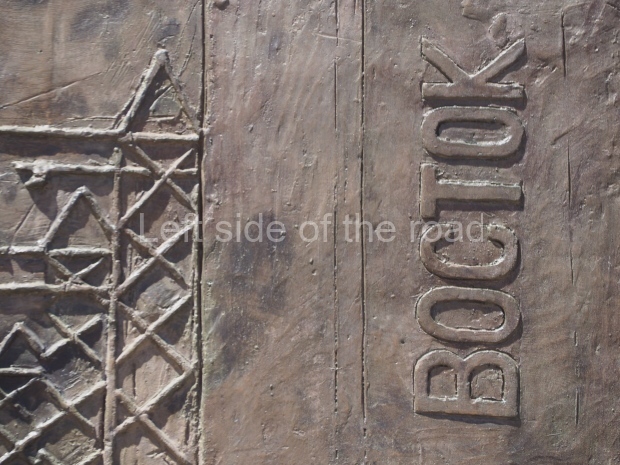

This is followed by images from the Great Patriotic War and the incident that led to the death of Aliya in 1944. It then takes a step 20 years in to the future with the launch of the Vostok rocket which sent the first human’s into space – all the Soviet space programme was based in Baikonur, in western Kazakhstan. Finally, we are faced with images that are supposed to represent modern capitalist Kazakhstan – a veritable heaven on earth.

Although I have issues with the panels behind the statue it is the representation of Aliya I found the most offensive and insulting (to her and her memory). This follows the same pattern that happened in Albania with another young, female victim in the fight against German Nazism, Leri Gero. In both cases the capitalist elements in power have sought to appropriate the heroism of these young women from the past to substitute for their paucity of heroism in their present. In the process they distort the reality of these two (although from different countries) very similar young people according to the little we know of them. They were simple, honest and dedicated fighters for their people and their country – and for that they paid the ultimate price.

This representations of them during Socialism followed a well worn and ‘traditional’ path. A simple three dimensional image in their memory. However, the modern ‘representations’ turn both of them into silly airheads who only think of their own pleasure and vanity. Leri looks more like a young woman going clubbing at the weekend and Aliya like a fashion model who has just flung off the jacket of a haute couture ‘army’ suit at the end of a catwalk.

By stripping Aliya of any real reference to her medal they take away the reason she is in that location in the first place.

But then this is the tactic. If you cannot obliterate their achievements just try and trivialise them.

Aliya Moldagulova – memorial park in Nedw Town

In Aktobe new town;

Memorial Complex;

Aliya Moldagulova Avenue, close to the Museum

GPS;

50.287698 N

57.152472 E

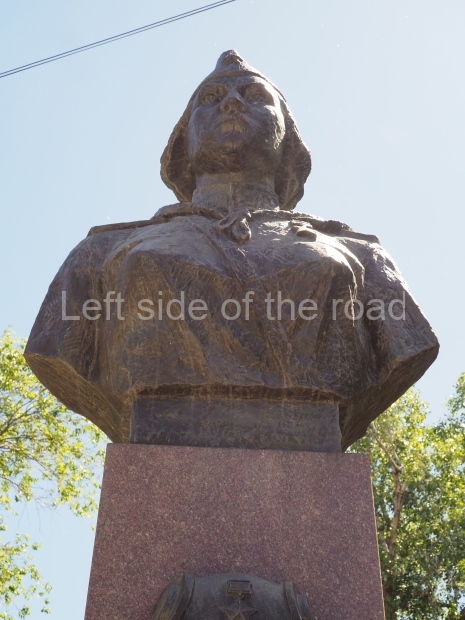

Monument in the Old Town

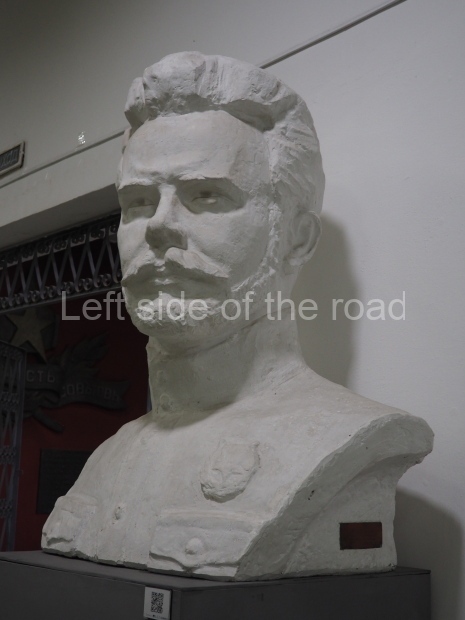

This is a much more staid and formal representation of the young woman. It is a bust, about 1.3 metres mounted on a high stone stele – giving a combined height of 3 metres. It stands at the entrance to a small green and garden space that leads off Shimize Street – opposite No 39 – in the older part of Aktobe.

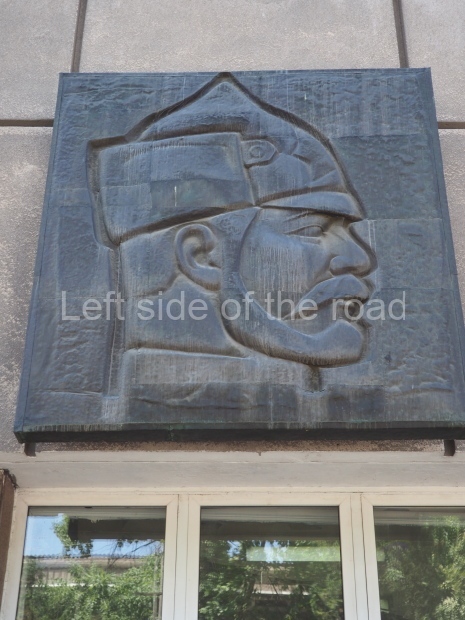

We have here a uncomplicated head and shoulders bust of a young woman in a basic and unadorned military shirt and with a military cap on her head. The only decoration is the Red Star on her cap and the medal of the Hero of the Soviet Union on her right chest.

The area around the monument is always kept neat and tidy and ceremonies in her remembrance, and of the Great Patriotic War in general, often take place in this small corner of the city.

This small monument has survived the somewhat turbulent times over the last 35 years or so which demonstrates the respect the people of the town (and the country) have for her – so many years after the end of the war. I would venture to guess that most people passing would know who she is, not something that could be said in many western countries to street sculptures commemorating individuals from the Second World War.

Aliya Moldagulova – in Aktobe Old Town

In Aktobe old town;

Location;

Shimize Street – opposite No 39

GPS;

50.1657 N

57.1336 E

Museum established in her honour;

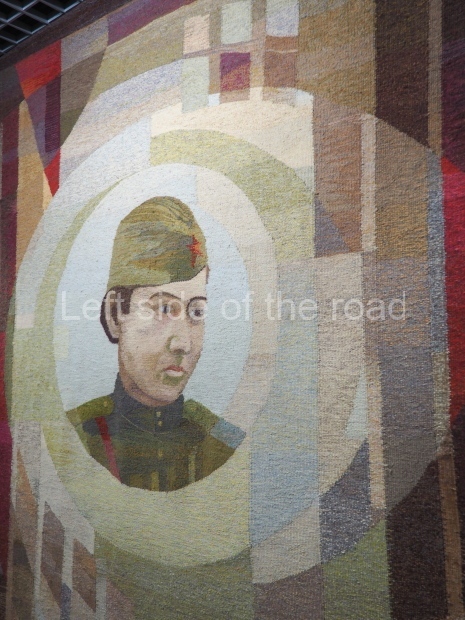

Finally, in Aktobe, a small museum was established in the newer part of town and opened on 22nd April 1985. This also operates as a research centre.

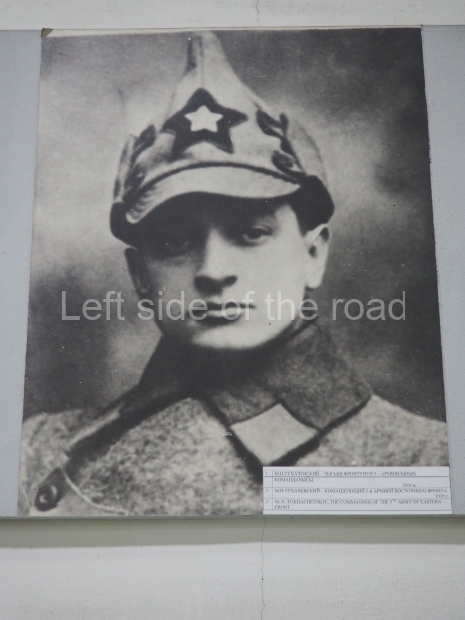

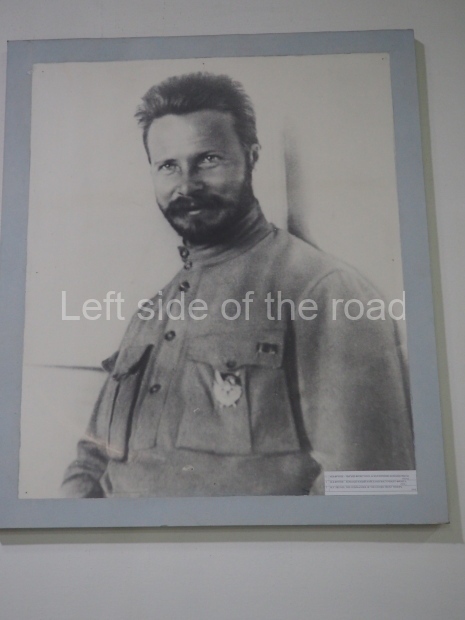

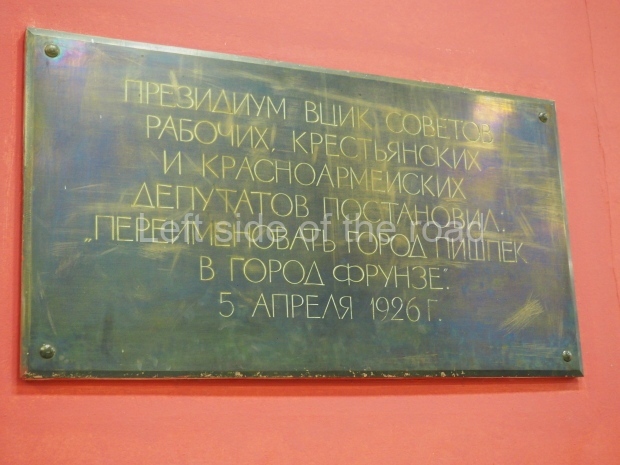

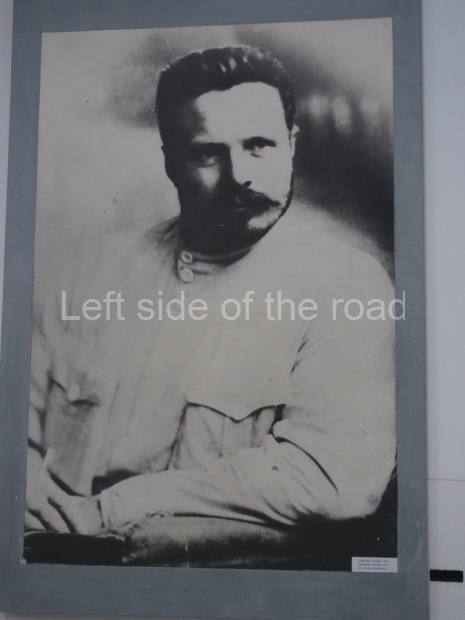

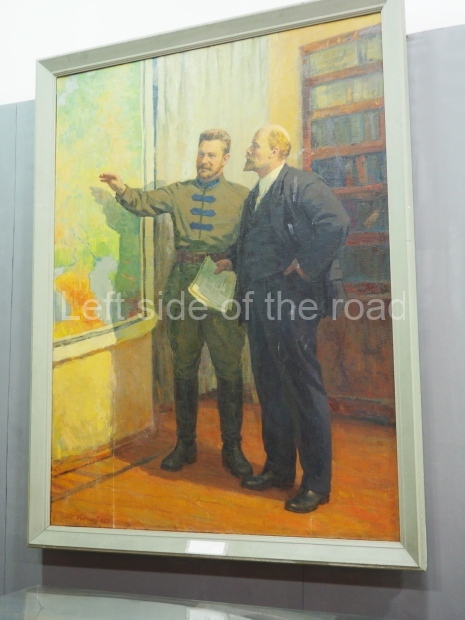

Aliya Moldagulova – image in museum

Free entry.

Opening;

09.00-18.00, closed for lunch 13.00-14.00

Location:

Aliya Moldagulova Avenue 47

GPS;

50.28877 N

57.15818 E