Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, Moscow

The Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute (Russian: Институт Маркса — Энгельса — Ленина), established in Moscow in 1919 as the Marx–Engels Institute (Russian: Институт К. Маркса и Ф. Энгельса), was a Soviet library and archive attached to the Communist Academy. The institute was later attached to the governing Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and served as a research centre and publishing house for officially published works of Marxist thought. From 1956 to 1991, the institute was named the Institute of Marxism–Leninism (Russian: Институт марксизма-ленинизма).

The Marx–Engels Institute gathered unpublished manuscripts by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and other leading Marxist theoreticians as well as collecting books, pamphlets and periodicals related to the socialist and organized labour movements. By 1930, the facility’s holdings included more than 400,000 books and journals and more than 55,000 original and photocopy documents by Marx and Engels alone, making it one of the largest holdings of socialist-related material in the world.

In November 1931 the Marx–Engels Institute was merged with the larger Lenin Institute (established in 1923) to form the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute.

The institute was the coordinating authority for the systematic organization of documents released in the multi-volume editions of the Collected Works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and numerous other official publications.

The institute included an academic staff which engaged in research on historical and topical themes. The institute included sections devoted to the history of the First and Second Internationals, the history of Germany, the history of France, the history of Great Britain, the history of the United States, the history of the countries of Southern Europe and the history of international relations. Also included were sections working in philosophy, economics, political science and the history of socialism in Slavic countries.

The main research orientation of the facility was towards history rather than other social sciences. By 1930, of the 109 employed by the Marx–Engels Institute, fully 87 were historians.

During its first decade, the institute published an array of books by the likes of Georgi Plekhanov, Karl Kautsky, Franz Mehring, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, David Ricardo and Adam Smith. The publication of the anticipated multi-volume works of Marx and Engels was started at this time (1927/28) in the form of two editions: An untranslated, complete edition (the first Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe), which was to comprise 42 volumes (12 of which were published until 1935 – then this project was discontinued), and a first Russian edition in 28 volumes (Sochineniya1), the 33 bound books of which were completely published by 1947.

The institute also published two regular academic journals, Arkhiv Karla Marksa i Friderikha Engel’sa (Archive of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels) and Letopis’ marksizma (Marxist Chronicle).

The Lenin Institute began as an independent archival project, established by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1923 to gather manuscripts with a view to publication of a scholarly edition of Vladimir Lenin’s collected works. This work was accomplished through the publication of a thick periodical called Leninskii sbornik (Lenin Miscellany), some 25 numbers of which were published between 1924 and 1933. The institute eventually became under the jurisdiction of the Central Committee as a department.

The mission of the Lenin Institute was expanded in 1924 by the 13th Congress of the Russian Communist Party to include the ‘study and dissemination of Leninism among the broad masses within and outside the party’, namely an enlarged purview which rendered obsolete the previously existing Commission on the History of the October Revolution and the History of the Communist Party. In 1928, Istpart was dissolved and its functions fully absorbed by the Lenin Institute.

The Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute was subsequently renamed multiple times. In 1952, the facility’s formal attachment to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was formally noted with the expanded moniker Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute of the CC CPSU (Russian: Институт Маркса—Энгельса—Ленина при ЦК КПСС). The name of deceased Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was added in 1953, with the institute formally becoming the Marx–Engels–Lenin–Stalin Institute of the CC CPSU.

This remained in place until the onset of de-Stalinization following the Secret Speech of Nikita Khrushchev in 1956. At this point, the name changed to Institute of Marxism–Leninism of the CC CPSU (Russian: Институт марксизма-ленинизма при ЦК КПСС). During this period, beginning in the 1950s, the institute was involved in the realization of major projects such as the publication of a second Russian edition of the collected works of Marx and Engels (Sochineniya2 with 39 basic and 11 supplementary volumes) and the comprehensive fifth edition of Lenin’s Collected Works (55 volumes). From the 1970s onwards, it also participated with foreign partners in the publication of the English-language Marx/Engels Collected Works (50 volumes) and the second Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe.

The name Institute of Marxism–Leninism remained unaltered for nearly 35 years, when turmoil in the Soviet Union brought about a name change to Institute of the Theory and History of Socialism of the CC CPSU (Russian: Институт теории и истории социализма ЦК КПСС). The institute formally ceased to exist in November 1991 following the fall of the Soviet Union, with the institute’s library and archive transferred to a new entity called the Russian Independent Institute for Social and National Problems.

The Central Party Archive of the institute was placed under the control of the Russian Ministry of Culture and eventually emerged as the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI).

Text above from Wikipedia.

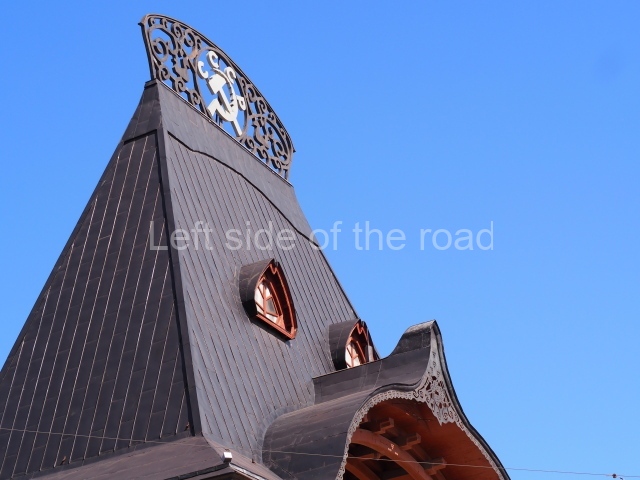

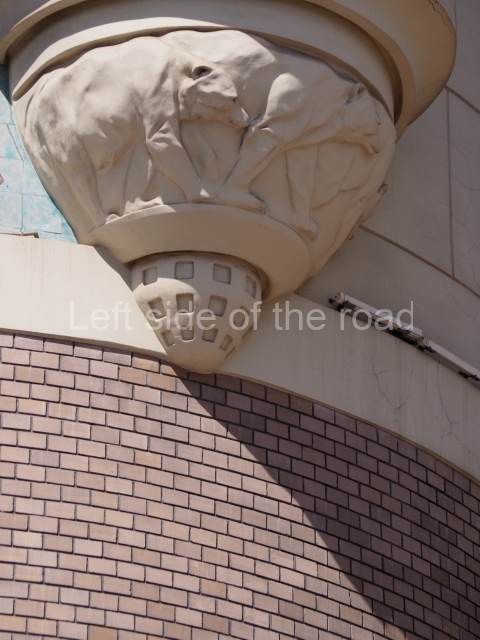

When the building was first opened the main entrance was facing Tverskaya Square, where there is now a statue of VI Lenin. At some time later, I assume when the building was expanded, the main entrance was moved to the new part of the building facing Ulitsa Bol’shaya Dmitrovka. At that time the bas relief images of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin were commissioned to decorate the new façade of the building.

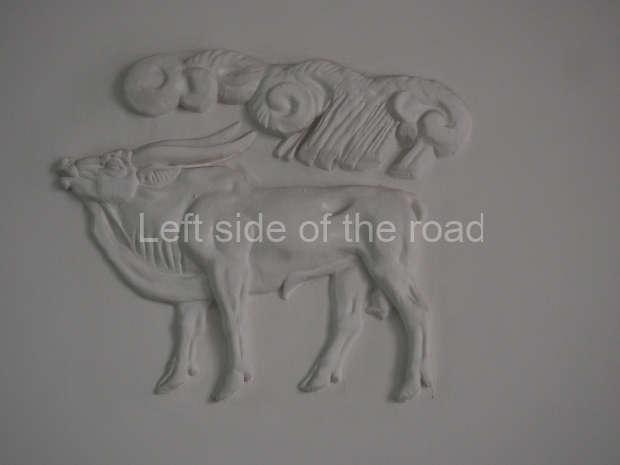

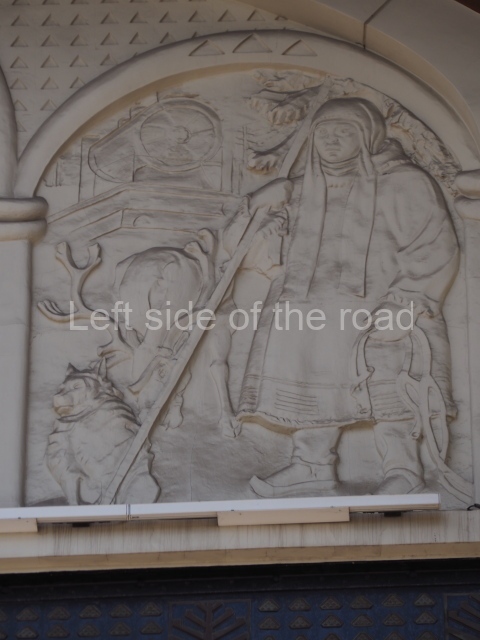

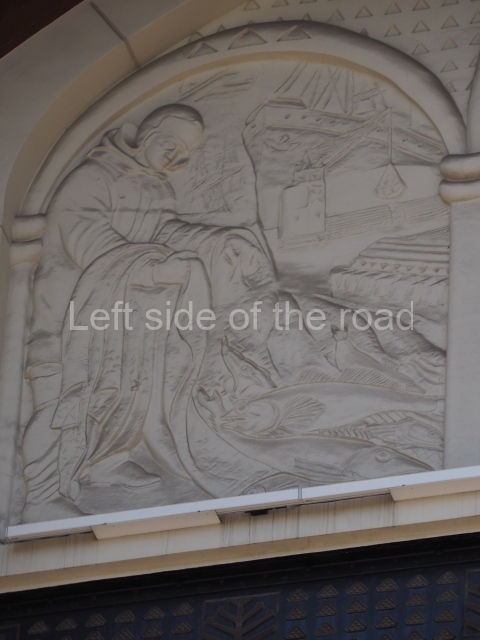

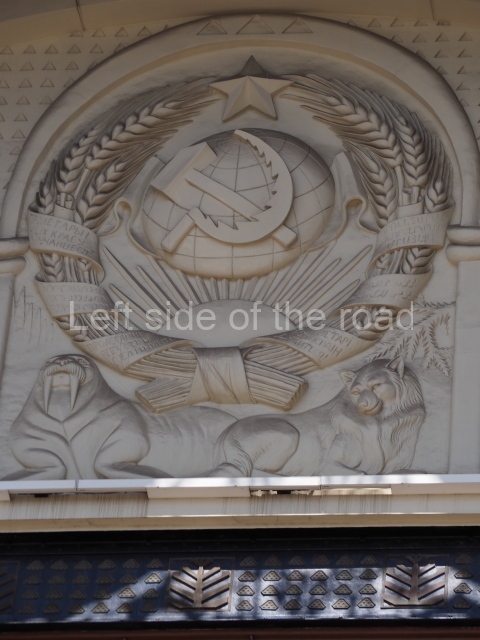

But they are not just simple bas reliefs of the great Marxist theoreticians. As part of the image aspects of their work was also included.

The three images are made of a bronze bas-relief and are on the first floor (UK designation) – above the main door and the glass frontages on either side of the entrance. There’s symmetry here as the space taken by the sculpture is exactly the same size as the space below. Each sector is bounded by a white border which contrasts with the beige of the building itself and which gives the three individuals their own space. From left to right they are;

Karl Marx

The image of Marx is based on various photographs that were taken in his later years, with long hair and a bushy beard. This is in the centre of the rectangle. In the bottom left hand corner is a small Greek Doric column. On top of the column there are a number of books but only one has a title, and that is Marx’s seminal work ‘Capital’. There appears to be a mask being crushed under the weight of Marx’s image and this seems to be making a reference to one of Marx’s ideas that the work of philosophers is not just to interpret the world (which it had been in the past) – but to change it.

In the bottom right hand corner there’s the image of a blacksmith. He’s wearing the blacksmith’s leather apron, stands behind a large anvil and is holding the the shaft of his hammer – the head of which is resting on the anvil – in his left hand and his right arm is raised in the air from which flutters the workers’ Red Flag.

Above the blacksmith (on the upper right hand side) a chimney rises to the sky, belching out smoke. This represents the industrialisation which Marx said created the proletariat, the wage slaves of capitalism.

Towards the top of the left hand side there is a group of four armed men, marching forward in unison. They look as if they are in a line going up a hill, their weapons pointing towards their adversary. By their hats they look as if they are from different epochs and different countries. This represents that the unified workers, over time and space, can only achieve their liberation through armed struggle – something which Marx started to stress following the defeat of the workers during the Paris Commune of 1871.

Across the top, cutting through the smoke coming from the factory chimney, is a banner with the words (in Cyrillic) ‘Workers of the World, Unite!’ – the very last words of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848).

Frederick Engels

The image of Engels is as can be seen, in Moscow, in the statue outside the main entrance to Kropotkinskaya Metro station.

In the bottom left hand corner we only see the two hands of a worker pulling asunder a chain. This is reference to ‘The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains’, the second to last sentence in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, which Engels co-wrote with his comrade Karl Marx. The backdrop to this image appears to be part of a machine and above this image there appears to be a collection of factory chimneys belching out smoke, reinforcing the idea it is industrial workers who will liberate humanity from oppression and exploitation.

The right hand side of the panel is dominated by a collection of images of workers making a revolution, specifically the Paris Commune – as was referenced in the panel of Marx. A lot is happening here in a small space.

First we have the full length image of a young woman, standing tall and upright, the hem of her long dress like a banner as she marches forward, her long hair also flowing behind her. In her right hand she holds a long sword which appears to be attached to a triangular banner with the words (in Latin letters) ‘Vive la Commune’ – ‘Long Live the Commune’. She holds the other end of the banner taut in her left hand. This female image originates much more from the (bourgeois) French Revolution of the 18th century rather than the Workers’ Commune of 1871, but it is the Spirit of Revolution that is being invoked here.

Above the banner we see little more than the heads of two male figures. The first is a member of the Parisian National Guard (we know that by his hat) and he is carrying a long rifle, with bayonet fixed, as he marches forward. Behind him is another man who is looking backwards as he encourages others to join the fight with his outstretched hand motioning them to follow the attacking forces. This is a common trope of Socialist Realist imagery. This is seen in many of the lapidars in Albania, for example, and also in Moscow itself on the monument to Lenin and the October Revolution opposite the Okysbrskaya Metro station.

The final part of this small tableau is a cannon. Only a part of the wheel and the barrel is seen, and the cannon has just been fired as it’s smoke merges with the smoke from the factory chimneys on the other side of the panel.

Why this emphasis on the 1871 Paris Commune in the imagery of the first two panels, those of Marx and Engels? The answer to that question is in what we see in the third panel, that of VI Lenin.

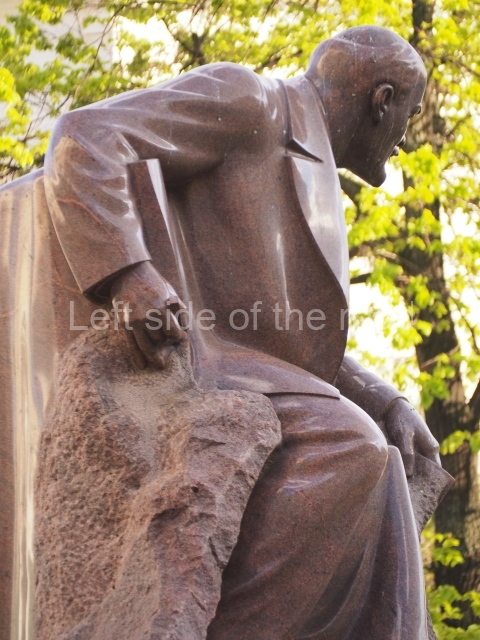

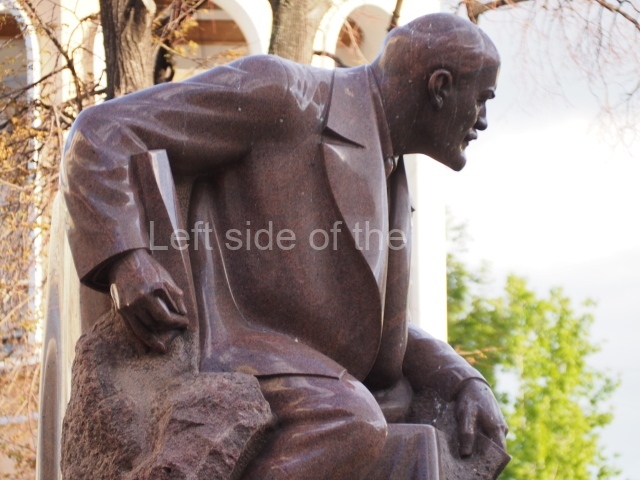

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

The images surrounding Lenin’s in this panel revolve around the events of the October Revolution of 1917 – and here is where we get the connection to the Paris Commune. If there was a ‘textbook’ for the Russian Revolution then it was Lenin’s pamphlet ‘The State and Revolution’, first published in August 1917. In preparation for this seminal work on a proletarian revolution Lenin studied all he could about the Paris Commune, its successes and its failures. Whilst in no way detracting from the huge cost the Parisian workers paid in their defeat (an estimated 40,000 were killed in the final week of the revolution) for daring to challenge capitalism’s right to rule it’s true to say that without the Paris Commune there wouldn’t have been the October Revolution – or at least one in Russia that was successful.

So what do we have here? We know we are seeing events from 1917 as that number cuts diagonally across the corner on the top left hand side. At the bottom, below the date, we have three, armed workers, marching forward in step. The first is a sailor (making reference to the role that the navy and especially those sailors from the cruiser Aurora – whose forward gun fired the signal for the start of the assault on the Winter Palace). Beside him is a woman revolutionary, with a rifle slung across her shoulder, expressing the idea that women – as in the Paris Commune – were prepared to take up arms for the cause of the workers. Finally, the third figure is that of a peasant in the uniform of a soldier in the Tsarist Army. His inclusion emphasises that the revolution was one of unified workers and peasants.

Above then, and below the year 1917, are two pamphlets with their subject written in Cyrillic. The top one is the Decree on Peace and the lower the Decree on Land. These were the very first decrees of the new Soviet power – and they were both part of the commitment the Bolsheviks made to the Russian population in the build up to the Revolution. The war (what later became known as the First Word War) had taken a heavy toll on the Russian people and they were sick of fighting for the moribund and corrupt Tsarist autocracy. The war ended as quickly as it took to transmit the decree to the frontlines.

In a predominantly peasant country the issue of land ownership was paramount and this was another promise that the Bolsheviks had made to the people. Taking all land under State control meant that the Party could later develop the system of State and Collective Farms and improve the lot of the peasants but it also created the conditions for the country to industrialise.

Both these decrees came into force the day after the Revolution, that is the 8th November (26th October Old Style), and can be read in ‘First decrees of Soviet Power’.

Above the decrees is an image of the sculpture – of a horse drawn chariot of the angel of Victory, with references to the Roman Empire – on top of the triumphal arch of the General Staff building of the Winter Palace complex. (This sculpture commemorates the defeat of the Napoleonic imperialist invaders of 1812 and is the work of Stepan Pimenov and Vasily Demuth-Malinovsky.) In 1917 the Winter Palace was the location of the Provisional Government and it was this building – amongst others in Petrograd – that was stormed when the signal was sent out from the nearby Cruiser Aurora.

Running across virtually the whole of the top of the panel are the words (in Cyrillic) ‘All power to the Soviets!’ This was another of the principal slogans of the Bolsheviks at the time of the Revolution, taking power from the bourgeoisie and placing it in the hands of organised workers and peasants.

The images on the right hand side move matters into the future. There’s a peasant working the land and a worker wielding a pick – and above them is a number of smoke belching factory chimneys, representing the later collectivisation and industrialisation of the country.

In the bottom right hand corner are three books on the spine of which is the name of Lenin, in Russian, English and French, here demonstrating the universality of Lenin’s ideas and theories.

To date I have no information on the artist or the date these images were created. I would estimate the 1970s (but that’s only a guess) and represent late Socialist Realist as although nominally a Socialist society reversals in the construction of Socialism begun in the mid 1950s continued apace.

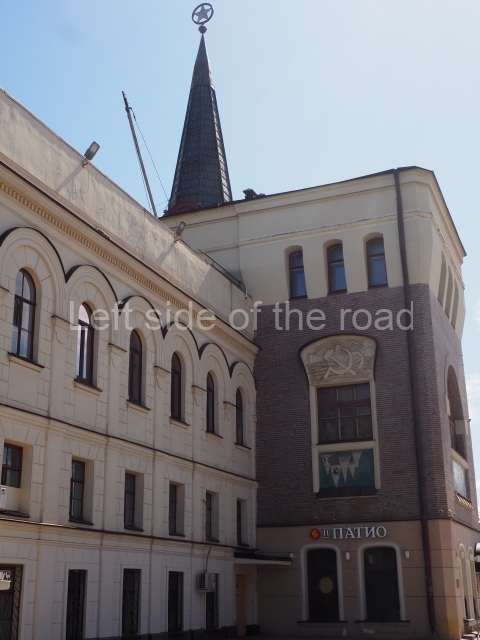

Location;

Ulitsa Bol’shaya Dmitrovka, 15, Moscow

GPS;

55.762851º N

37.613168º E