Tirana Martyrs’ Cemetery Approach

More on Albania ……

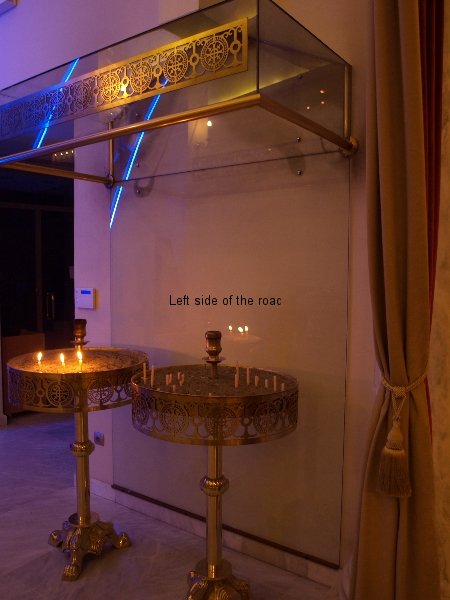

National Martyrs’ Cemetery – Tirana

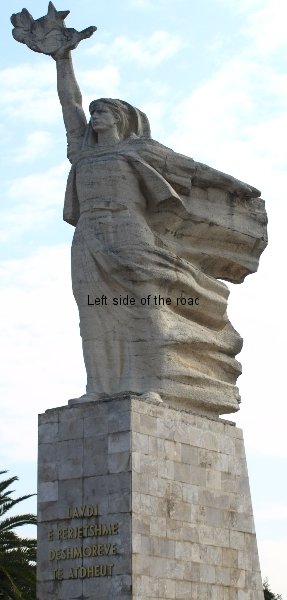

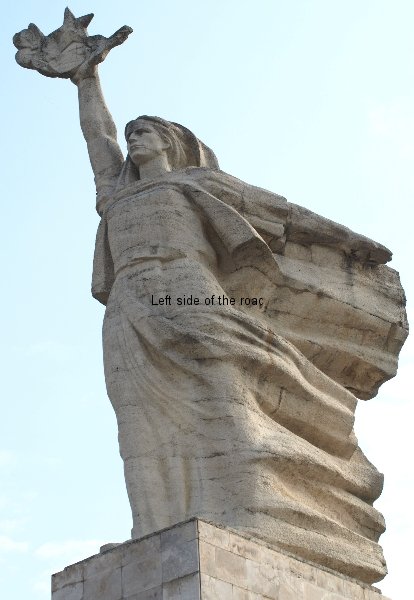

The National Martyrs’ Cemetery, Tirana, is the most important monument to those who fell in the struggle against Italian and German Fascism between 1939 and 1944. It’s also the location of one of the largest examples of Socialist Realist sculpture in the country – Mother Albania.

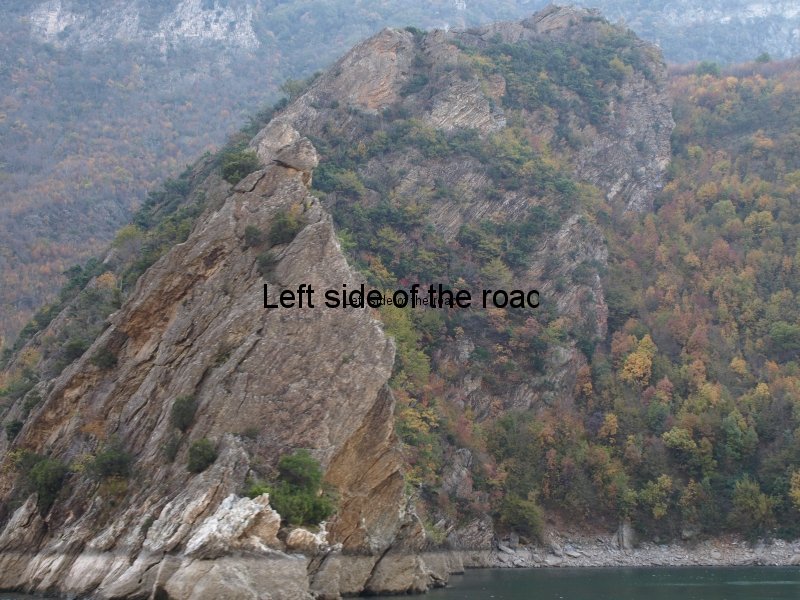

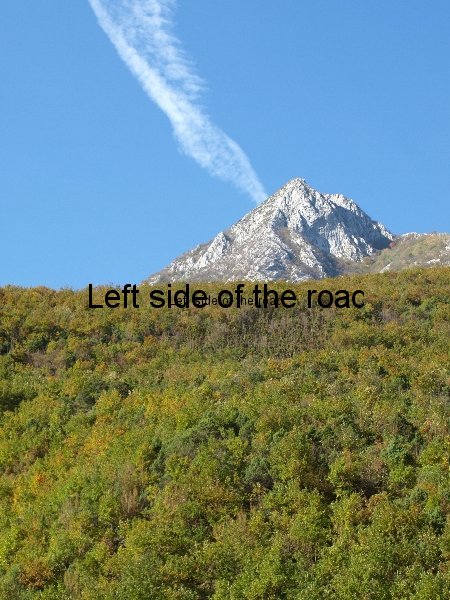

The cemetery is on a high point looking down on Tirana and offers a fine view of the mountains that surround the city, including the Mount Dajti National Park over on the right (as you look down on Tirana).

National Martyrs Cemetery – 1972

From the entrance gates you go along a wide road and then turn to the left to go up the steps, from the bottom of which you get the first view of Mother Albania. At the top of the steps there’s a plateau where celebrations on Liberation Day (29th November) took place.

National Martyrs’ Cemetery – 1976

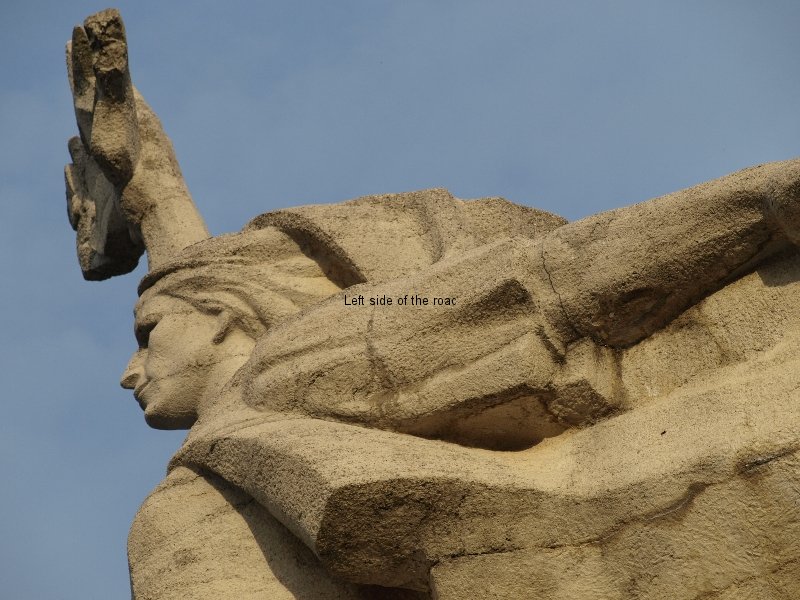

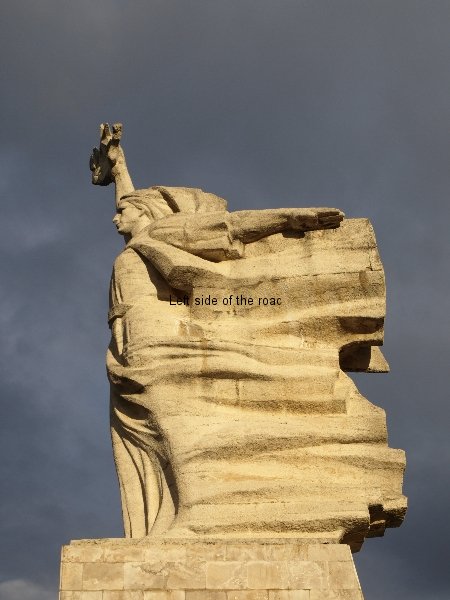

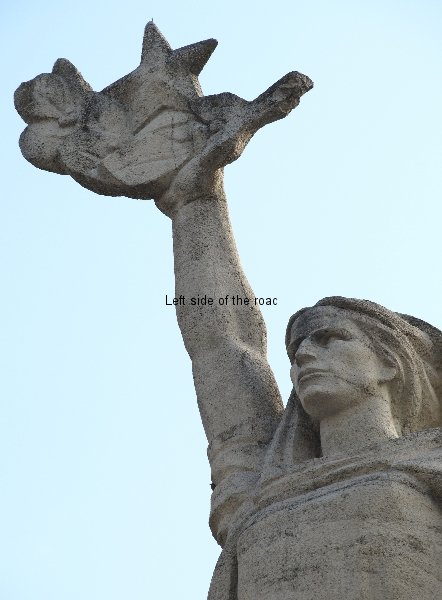

Dominating this area is the statue of Mother Albania. She has a cloak that seems to be blowing in the wind and her right arm is raised high above her head. In her hand she holds a wreath of laurels, celebrating the Partisans who died in liberating their country from Fascism, and a star, the symbol of Communism.

Tirana Martyrs’ Cemetery – Mother Albania (detail)

Three sculptors are credited with its creation (Kristaq Rama, Muntaz Dhrami and Shaban Hadëri) and was dedicated in 1971. It’s 12 metres high and made of concrete. (Many of the monuments in Albania are made from concrete, more so than normal from my experience, and it will be interesting to see how they weather.)

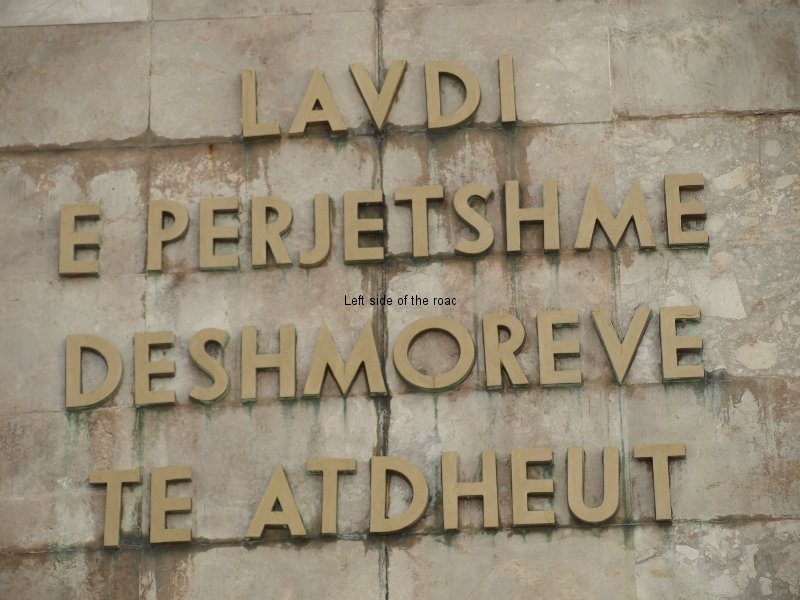

Engraved on the pedestal are the words “Lavdi e perjetshme deshmoreve te Atdheut” (“Eternal Glory to the Martyrs of the Fatherland”).

‘Mother Albania’ in the studio

Some of the other monumental sculptures by Kristaq Rama are the Independence Monument in Vlorë and the statue of Mujo Ulqinaku on the Durres waterfront.

On the hill surrounding this plateau are the graves/monuments to 900 partisans. There’s a laurel leaf on all of them and the Communists have the addition of a star above that to show their political allegiance.

Tirana Martyrs’ Cemetery – Partisan Memorials

At one time there was only one grave separated from the others, the one to Qemal Stafa after whom the National Stadium in the university area is named. He was one of the founding members of the Albanian Communist Party and leader of its youth section. He died in the war against the Italian Fascists at the age of 22 and May 5th, the anniversary of his death, is Martyrs’ Day, when, in Socialist times young children would go to the memorials throughout the country and place flowers on each grave as a sign of respect and also to remember that freedom doesn’t come without sacrifice.

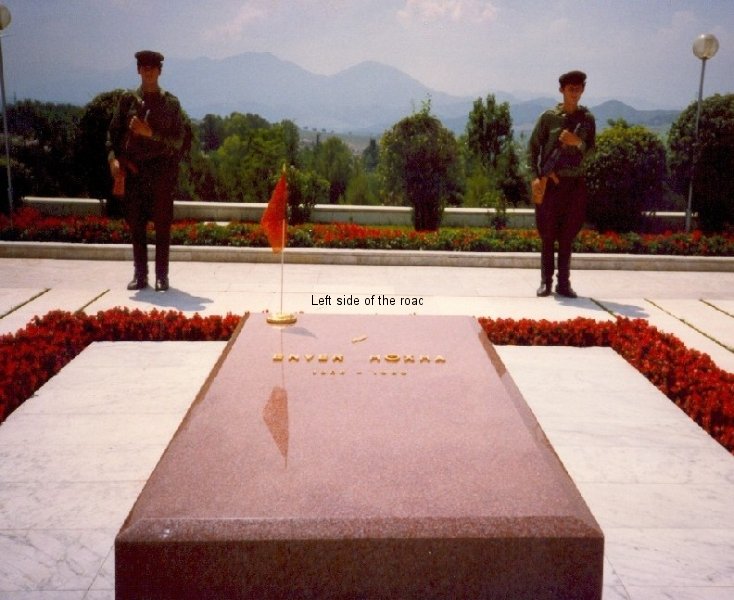

Tirana Martyrs’ Cemetery – Qemal Stafa’s Tomb

For a short time, the tomb of Enver Hoxha, the leader of the Party of Labour of Albania (as the Communist Party was called after 1948) was between the statue of Mother Albania and Qemal Stafa’s tomb. In April 1992 he was disinterred and reburied in Tirana’s municipal cemetery at Kombinat and the red grave stone re-used in the cemetery for the English dead in Tirana Park.

Tirana Martyrs’ Cemetery – the site of Enver Hoxha’s tomb

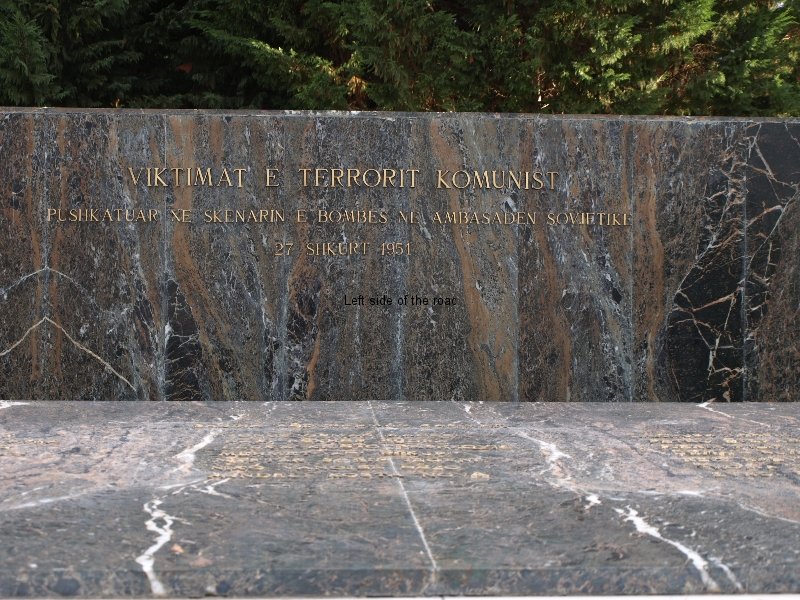

To the left of Mother Albania is a monument to 22 Monarcho-Fascists who were executed on 26th February 1951 for their implication in the bombing of the Embassy of the Soviet Union in the centre of Tirana. The installation of this large, black marble monument in the cemetery constructed to commemorate those who died fighting Fascism is an indication of the political stance of the present ruling politicians in Albania. They also established a monument to the German Fascist invaders who died in the country, close to the English cemetery in Tirana Park.

Tirana Martyr’s Cemetery – Fascist Memorial

This is a quite place, away from the chaos and noise of the traffic that is gradually suffocating the city centre and often you will encounter groups of old men taking the sun and playing chess on the steps up to the plateau.

I was surprised, no shocked, on my visit in October 2014 to find that a new tomb had been installed in a place of honour in the proximity to the Mother Albania statue. This was of Azem Hajdari one of the counter-revolutionary leaders of the student movement of 1990-91. He was courted by the North Americans and rose to positions of power within the post-Communist right-wing governments.

He was killed in an ambush in 1998. He wasn’t there the last time I visited the Martyrs’ Cemetery in 2012 and haven’t been able to find out exactly when he appeared. I would assume on the anniversary of either his birth or death and looks like it was one of the last actions of the right-wing government when it knew it was on the way out – however sycophantic it had been to the European Union and the United States.

This appears to be an extension of the idea of the ‘extirpation of idolatry’ that I suggested was the reason for the re-cycling of Enver Hoxha’s tomb stone as the principal monument at the English Cemetery in Tirana Park.

Azem Hajdari

This modern-day tomb must be, more or less, in the same position as the original resting place of Enver Hoxha. By placing Hajdari’s tomb here the reactionary country-sellers are making a statement of who is now in control.

Originally the Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout the country were intended to remember and commemorate those who had given the ultimate sacrifice to free their country from the Fascist invader – exceptions were only made in a few special circumstances, e.g., Enver Hoxha who was the leader of that struggle which led to the liberation and real independence of the country.

As with the destruction, deterioration or alteration of monuments of the Socialist period (for example, the ‘renovation’ of the Albanian Mosaic on the National History Museum) the past is being re-written. I have no problem with the destruction of monuments when the revolutions or counter-revolutions occur. I made this point when VI Lenin and JV Stalin were put ‘under wraps’ in November 2012.

But capitalism is parasitic. Sometimes it destroys the past that is antithetical to its ideology, at other times it attempts to appropriate and use it for its own political aims. The battle is unending and their ‘reversals’ will themselves be reversed.

The Evolution of a Lapidar

The original lapidars in Albania had a very humble beginning. The first ones to be constructed were at cemeteries of those Communists and Partisans who died in the National Liberation War and were monuments to their memory.

Also, in the early days of the Albanian Socialist Revolution there weren’t the resources, and possibly the artistic and technological skills, needed to produce the really fine monuments such as the Drashovice Arch or the Pishkash Star. As the country recovered from the devastation of war and those educated under the new system reached their maturity the obstacles of the past receded and the monuments could become more adventurous.

Original Martyrs’ Cemetery lapidar

The original National Martyrs’ Cemetery was located in Tirana Park, the area behind where Tirana University is to be found today. It was established in 1945 and was a very simple affair. The monument was an actual lapidar, that is, a monolith – an obelisk that was very wide at the base but tapering towards the top. There was a large red star fixed to the top and on the side facing the cemetery there was fixed a large marble plaque. There was another red star at the top of the plaque but, so far, I’ve been unable to discover the text.

The graves had simple wooden markers with the name of the martyr and their dates. There didn’t seem to be a great deal of shrubbery in the vicinity.

At that time there wouldn’t have been the same number of trees in the park as there are now and the lapidar would have stood out on the skyline.

Memorial stone to original Martyrs’ Cemetery

This location is commemorated by a large rock, one side of which has been worked and on a marble plaque are the words:

Ne kete vend prej vitit 1945 deri ne vitin 1972 kane qene varrezat e deshmoreve t’atdheut

This translates as:

The National Martyrs’ Cemetery was located here from 1945 to 1972

The decision to construct a cemetery that was a suitable memorial to those who had died, allowing those that remained to attempt the construction of Socialism, and the commissioning of the Mother Albania statue, of necessity, meant that the site in Tirana Park was not adequate.

The sheer scale of the statue meant that it had to be located in an area where it could breath and now she surveys the city and the surrounding countryside in all her glory.

GPS:

Of Mother Albania

41.30862703

19.84004502

DMS:

41° 18′ 31.0573” N

19° 50′ 24.1621” E

Altitude:

210.4m

Practicalities

Getting there:

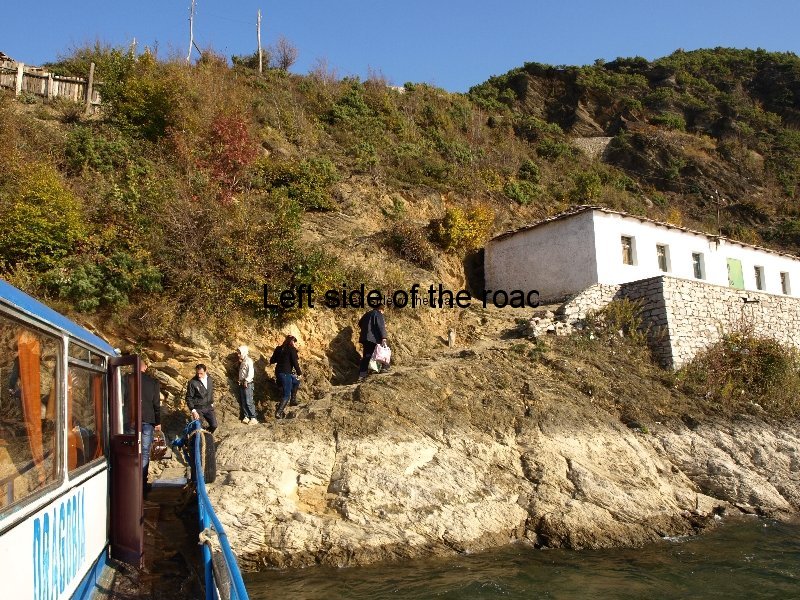

The Qender-Sauk bus leaving from the bus station between the clock tower and the National Library, off Skënderbeu Square, passes the cemetery gates and then it’s just a short walk up the steps to the statue of Mother Albania. All local buses in Tirana have a set fare of 30 leke (which hasn’t changed in at least three years).

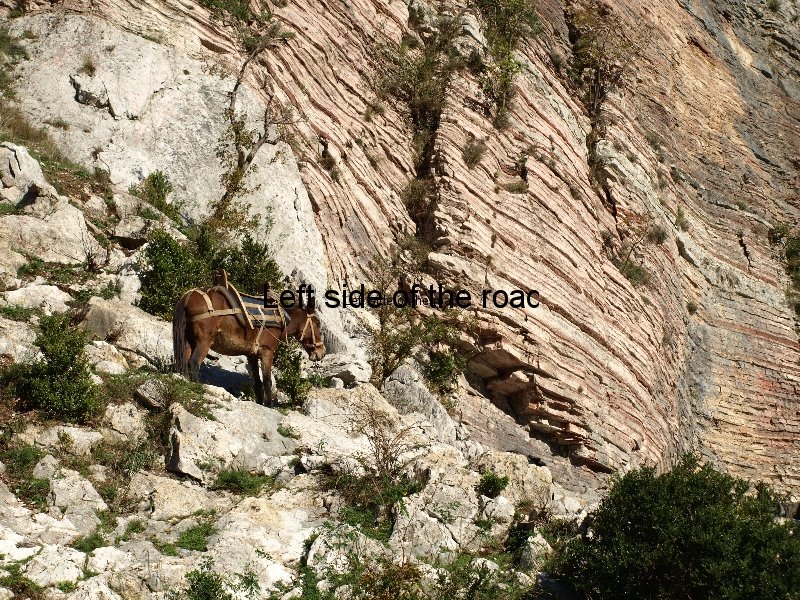

The cemetery is at the top end of Rruga e Elbasanit which starts just after crossing the Lana River. You then pass the US Embassy on your left, but being the US it’s not just a building but half a district. You then pass by University buildings before starting the climb up the hill. Look out the left hand side of the bus for the statue of Mother Albania and get off at the stop opposite the entrance to the memorial. The large gates might be closed but it’s always accessible to pedestrians. During the day the bus runs every 10 minutes or so and the journey only takes a few minutes after passing the University buildings.

GPS:

Of original site

41.31461003

19.821303

DMS:

41° 18′ 52.5961” N

19° 49′ 16.6908” E

Altitude:

135.2

More on Albania ….