Monument to Heroic Peze

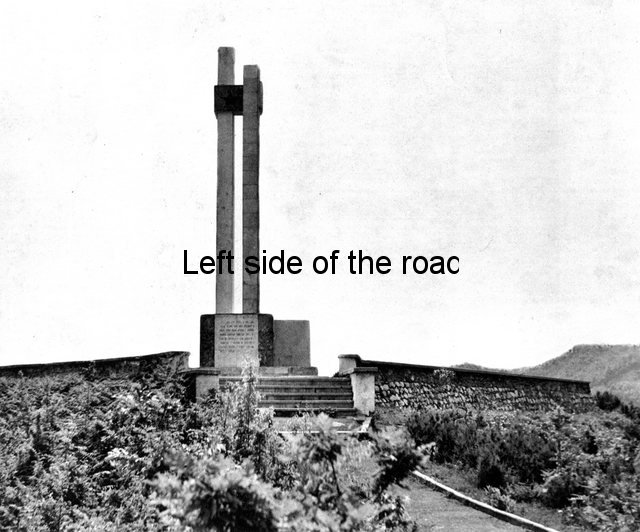

Looking like a cross between a pistol and a huge road sign, the Monument to Heroic Peze sits at the junction to the village of Peze, along the old road between Tirana and Durres. This huge block of concrete, in its imagery and words, tells the story of the important role that this small village played in the war against fascist occupation (both Italian and German), the formation of the National Liberation Front and the concept of People’s Power.

The monument (Monumenti kushtuar Pezës heroikë – Monument dedicated to Heroic Peze) was inaugurated in September 1977, on the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the Albanian National Liberation Conference in Peze (the village being only 6 km from the junction where there are other monuments to the fallen, the local guerrilla unit and the conference) and is the work of sculptors Mumtaz Dhrami (who was also involved in the creation, among others of Mother Albania in the National Martyrs Cemetery in Tirana and the Monument to Independence in Vlora) and Kristo Krisilo. It symbolises the struggle and glorious history of the people of this region led by the Communist Party of Albania (which became the Party of Labour of Albania during the period of socialism) in the war for liberation of the country against Italian and German Fascism.

The engraving above, by Fatmir Biba, records the inauguration in 1977

When I first saw this monument in 2012 it was just plain, undecorated concrete but between then and November 2014 it had been whitewashed and then certain images, principally the stars, the double-headed eagle and some of the text, have been picked out in red and black paint. When I first saw this change in the fate of the Monument of Dema, near to Saranda in the south of Albania, I thought this was just a local change in attitude, care and maintenance rather than disregard and vandalism, but this is obviously a much more extensive approach towards the patrimony of the country.

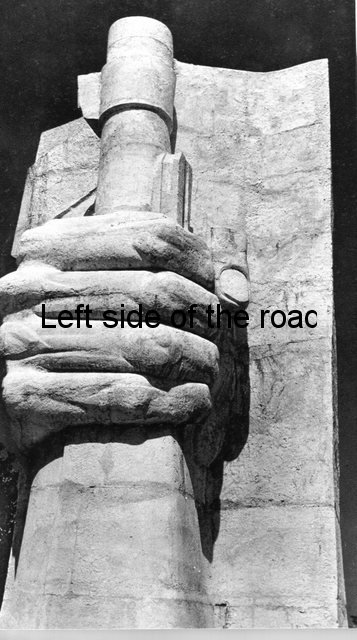

On the edge facing Tirana

On this part of the monument there is less of a story rather more a symbolic representation of what the struggle meant to the Albanian people. From the right hand side, that closest to the main road, there’s an image of a woman facing in the direction of Tirana, seeming to look into the distance towards the capital. She’s an older woman from those normally found on such monuments, as you can make out the creases in her forehead and also her dress is not of a combatant, more of a woman of the countryside, with a scarf covering her head and on both sides of her face. Is she, possibly, a representation of Mother Albania?

It’s not quite clear but she seems to holding the top end of the barrel of a rifle in her hand. That fits in with the many other images of armed women in Albanian Socialist Realist Art and it would be somewhat strange if this is the rifle of the man to her right.

Next we have the heads of three men, all of whom are looking in the direction of the village of Peze. Are we getting here a link between the capital and Peze? Without the conference and the anti-Fascist organisation that resulted in it the chances of victory and the liberation of the capital would have been reduced.

These heads represent the unity within the country, from the Communist (who is closest to the woman and whose star on his cap is now painted red and who has a bandolier across his shoulders) to the facial characteristics of Albanians from different parts of the country, symbolising that victory was a nation wide achievement. For such a small country and tiny population there are a huge number of distinctive facial differences between those in the north and those in the south. The third male from the woman also seems to be wearing a sheepskin collar to his jacket (similar to the separate, standing individual on the other side).

In front of them a disembodied hand holds high what looks like a bayonet, again pointing in the direction of the village. In front of this are the words, in Albanian, “Populli në këmbë, partia në ballë” that mean: “The People standing up, the Party in the vanguard.” And next to these words a large star, now picked out in red.

Underneath the faces are the words: “Lavdi Pezës heroike ku u vunë themelet e Frontit Nacional Çlirimtare dhe të pushtetit popullor”, which translate to: “Glory to Heroic Peze – where were laid the foundations for the National Liberation Front and People’s Power.” The larger, first words now also painted red.

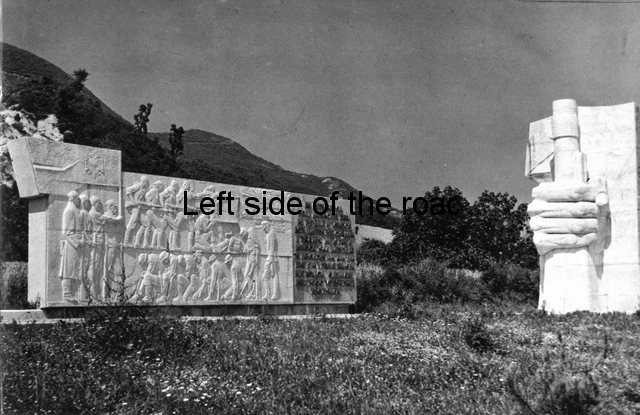

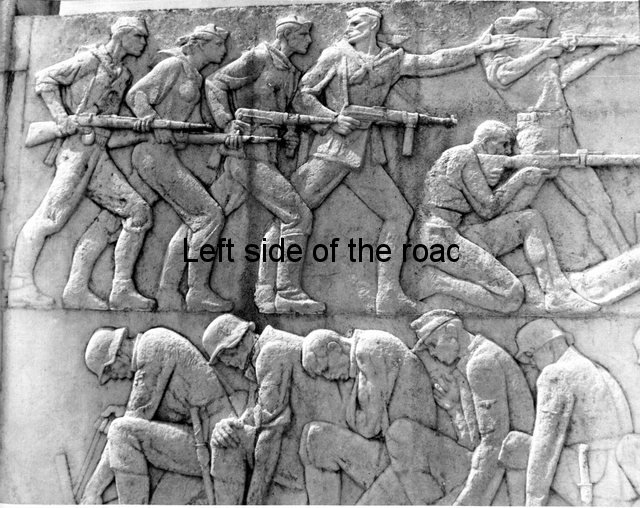

The facade towards Durres.

From the left the letters VFLP, now picked out in alternate red and black, an initialism for “Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!” (“Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!”) a slogan and an oath which Partisans used to express their unity of purpose.

Then there’s the slogan in Albanian: “Historia e Pezës dhe e popullit të të gjithë kesaj krahine është një histori e lavdishme që do të na frymëzojë në shekuj” which means: “The story of Peze, and of all the people of this province, is a glorious history that will inspire us through the centuries.”

Then there’s a male Partisan fighter, standing with one leg higher than the other as if he were climbing a mountain. His right hand is raised above his head in the revolutionary salute, with the clenched fist. He is wearing a cap with a red star (but this hasn’t been picked out in red with the recent painting). The butt of his rifle, the barrel of which he holds in his left hand, is resting on the ground. His shirt is open at the neck and hanging from his shoulder, on a strap across his chest, is a water bottle. Around his waist he wears a bandolier holding spare cartridges and on his right hip rests a British made Mills bomb (fragmentation grenade). His jacket seems to lined with sheepskin as it looks like a fleece showing where it is open.

To his left is a çeta (guerrilla unit) of 12 marching towards Peze, both in the sense that they head to the village which is 6 kilometres from this junction and also to the buildings depicted on the monument itself. The face of the topmost of the group, towards the back, has suffered damage and only half the face exists. There’s only one woman Partisan and she is in the middle with a light sub-machine gun in her right hand, relaxed downwards as they are not in a combat situation. Not all the weapons of the group are shown but one of the male Partisans, in the middle, has his rifle raised above his head, extending over the heads of those in front and behind him.

There are faint red stars (again not picked out in red since the recent painting) on most of the caps worn by the group, including the cap of the female. The fourth male from the front carries a pole and the flag flutters over his head. On this flag there’s the double-headed eagle and star – but again these are faint and haven’t been highlighted in the recent cleaning/renovation.

In the arms of one of the leading males is a woman, in the traditional dress of the time, with her face very close to his. This is, presumably, his wife as just behind and below her is a young boy in the process of running to his father.

They have just come from Peze which is represented by the a few buildings up a hill side, towards the front of the monument. Superimposed over the houses is a large (now) red star, providing the accolade that was given to Peze during the time of socialism – Red Peze for having played a pivotal role in the formation of the National Liberation Front. Underneath are the words “Pezë,16 shtator 1942” which translate as: “Peze, September 16, 1942”, the date of the Conference. The name of the village is now painted red and the date in black.

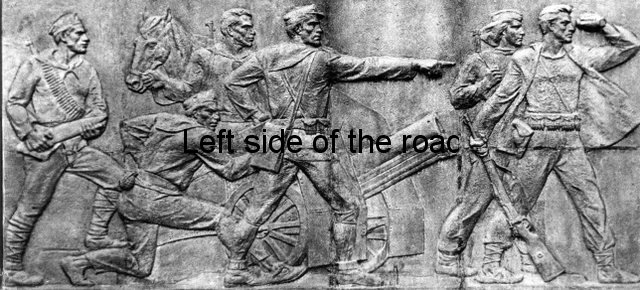

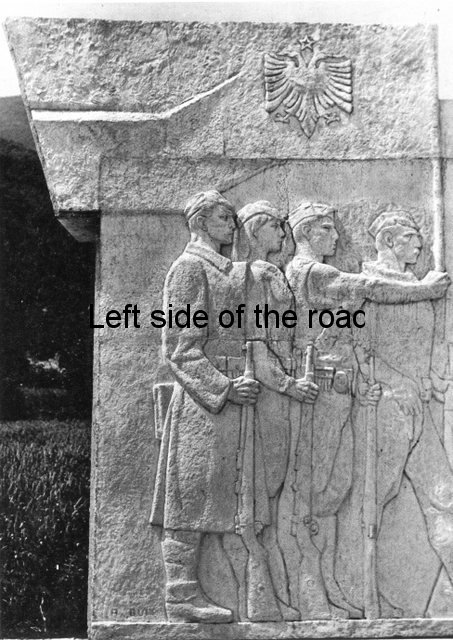

The narrow facade facing the main road.

This is a battle scene. On the immediate left is a depiction of the double-headed eagle, with a large red star above the heads. The eagle has been painted black and the star a bright, crimson, revolutionary red.

To the right of that is the battle scene itself. This is not really that easy to make out, this edge facing more or less north and never really getting the sun on it to bring out the shadows of the relief. Also, because of its northerly aspect it has been subject to more weathering, not serious damage as far as I could see, but there’s staining that would come from the dampness staying on that part more than the two larger faces.

First there’s a male Partisan, down on one knee and in his right hand he holds a stick grenade (almost certainly ‘liberated’ from the Nazi invader and now being returned to the rightful owner) which he’s just about to throw. In his left hand he holds a rifle which is pointed in the direction of the enemy. He’s bare-chested, his shirt flying out behind him as he puts all his effort in throwing the bomb.

On his left, close together and all pointing and firing their rifles in the same direction, are 4 Partisans, three male and one female. The second male wears a fez cap, typical of the people from the area at the time, and the woman of this group wears a cap, which would normally have a red star on the front but it’s difficult to make that out due to the weathering. They are on a slight diagonal going up from left to right.

Behind this group stands a male partisan with a rifle, but not one that is firing at the enemy. He is looking back and I can’t make out at what, if anything. It also looks to me that there may be a flag attached to his rifle which is flying back over his head. This might represent the call for others to come and join the battle.

To his left there is a woman fighter firing a machine gun supported on a tripod. Behind her and barely visible is another fighter wearing a conical, felt hat typical of the north. His rifle is over her left shoulder pointing in the direction of the enemy.

I’m not sure if it’s just the weathering but above her head it appears to be the image of a building, if so this would be a representation of a building that would have been normal in Peze at the time of the beginning of the war – virtually all of Peze was razed to the ground during the National Liberation War.

GPS:

N 41.25917103

E 19.69045102

DMS:

41° 15′ 33.0157” N

19° 41′ 25.6237” E

Altitude: 63.4m

Getting there by public transport.

There are regular buses (every ten minutes or so during the day) leaving from the centre of Tirana which have the destination of Ngoc. The Tirana terminus is a short distance from Skanderbeg Square on Rruga Karvajes, opposite the German Hospital and just a few metres east of Rruga Naim Fresheri. Cost is 40 lek. Just wait by the side of the road, just a short distance up the hill, to go back to Tirana. This route also passes the road that leads to the cemetery where the grave of Enver Hoxha is located, in Kombinant. The bus that goes off the main road to Peze is less frequent and details can be found on the post for the Peze Conference Memorial Park.