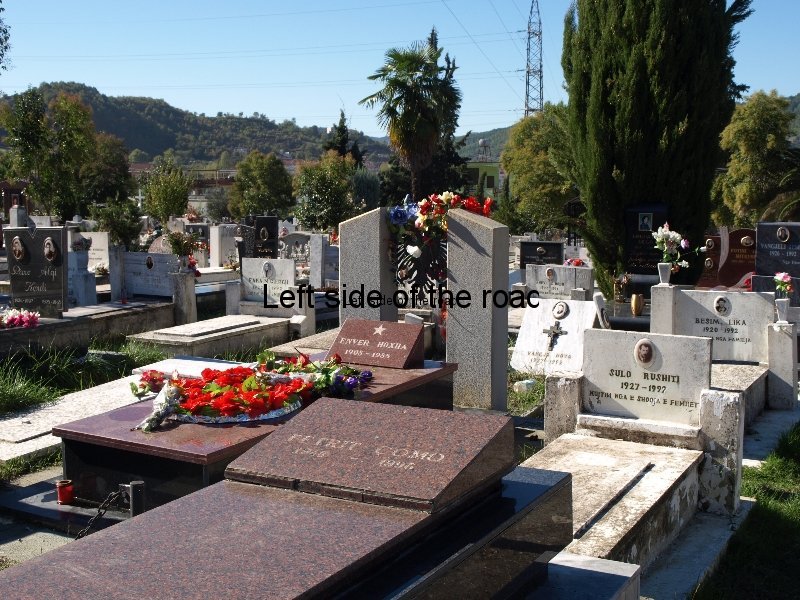

Panagia Monastery Church – Mother of Christ – Dhermi, Albania

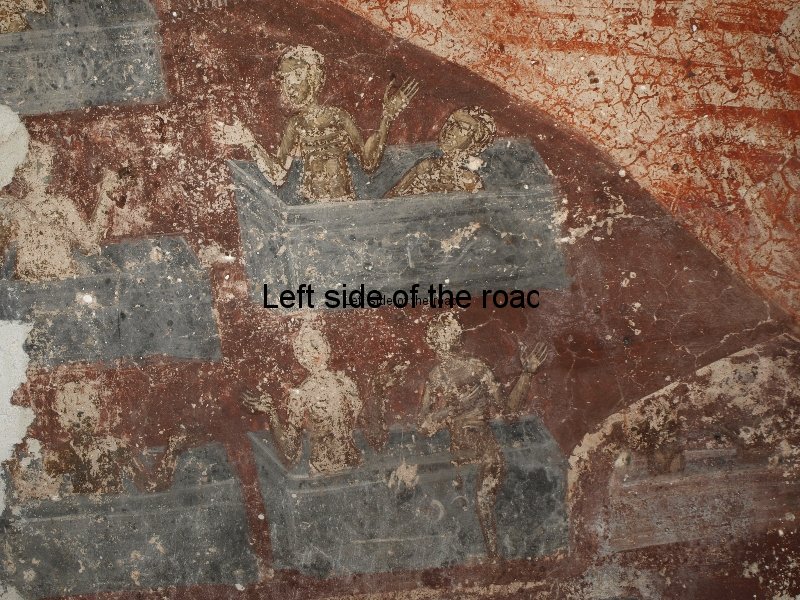

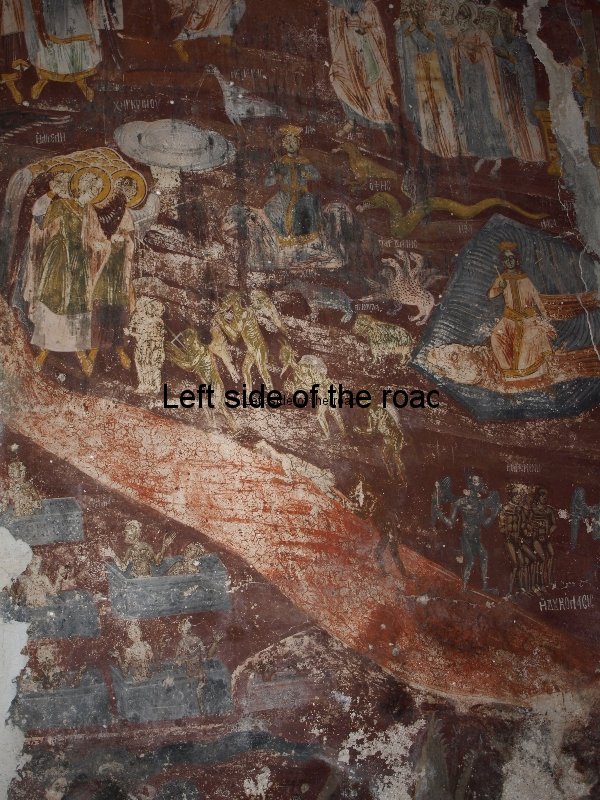

The rear wall of the Panagia Monastery Church – Mother of Christ – in Dhërmi, Himara province, southern Albania, warns sinners of what’s in store for them if they don’t repent.

Over the years I’ve been inside hundreds of churches and Cathedrals, mainly Catholic or Protestant, and each time it’s been on the look-out for something unusual, different from the norm. For example, the huge (unreal) guinea pig on the table of the Last Supper in Cuzco, Peru, or the black Christ and two Marys in a church in Lorca, in Spain.

But Greek Orthodox churches are new to me and its only in Albania that I’ve had the chance to go inside a significant number of them. And for me they are generally not very interesting. The layout is virtually the same: the rood screen at the front, behind which there is the altar; on the screen there will be the same collection of icons, of Christ and the Apostles; and around the walls there will be icons of other saints, depictions of their miracles and/or martyrdom. The only variant seems to be in the wealth or otherwise of any particular church, some having (from where I know not) acquired huge amounts of money to pay for the silver images on the rood screen, the fine painted icons that decorate the walls or the chandeliers.

When I went inside a new Orthodox church in the small village of Dhërmi, which is along the coastal road from Saranda to Vlore, in the southern part of the country, a woman who was something like a caretaker encouraged me to go to the centre of the church and look at all this silverware with the words ‘Buker, jo?’ (‘Isn’t it beautiful?’) Impressive perhaps, but not the sort of artwork that does much for me.

This has been taken to the ultimate in the Greek Orthodox Cathedral in the centre of Tirana, opened on 24th June 2012.

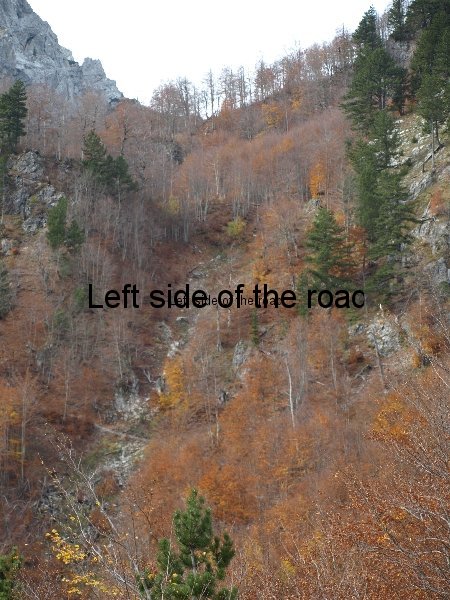

At the opposite extreme to these clean, almost pristine, new buildings are the ancient churches and monasteries that exist throughout the country. Some of these go back centuries and they are interesting as they are very much in the style of the Romanesque churches that exist in western Europe, a style I’ve grown to like over the years, mainly for its primitiveness, honesty and naiveté.

A couple of those I’ve been able to see were in a really sad state. These were two small churches in the Old Town of Himara. This area had been abandoned I don’t know how many years ago as I’ve drawn a blank when looking for information about when the people decided to live lower down the hill.

These two churches had suffered from damage which I imagine was a mixture of vandalism (the area was always being fought over by different armies) and just simple neglect. In a country which declared itself the first atheist state in the world in 1967 it is sometimes forgotten that churches have been left to go to ruin throughout history, throughout the western world, even in countries that considered themselves deeply and profoundly religious. Therefore not every ruined and abandoned church is as a result of a political act, although political opponents will suggest it is.

In fact, it was the Government of the People’s Republic of Albania that declared these two churches part of country’s heritage in 1963, providing the buildings with a certain amount of protection, indicating that neither the church authorities nor the local populace were taking care of the structures themselves.

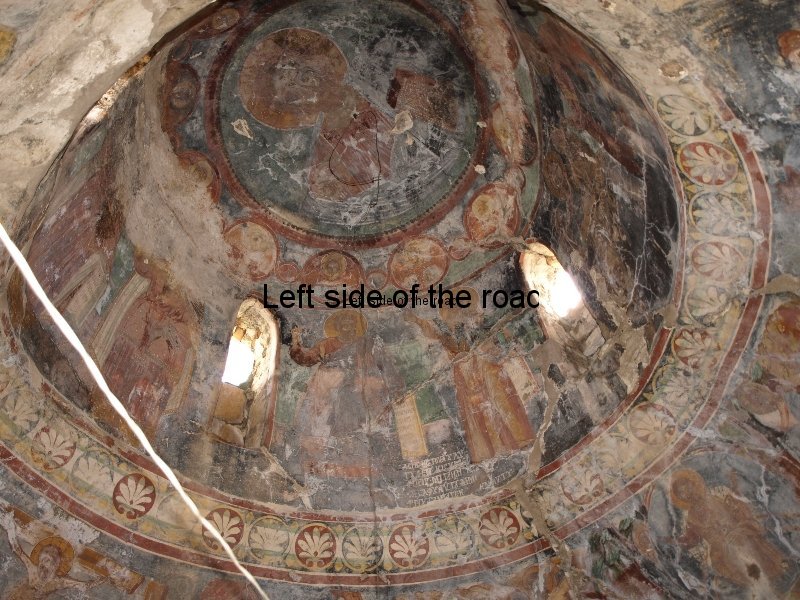

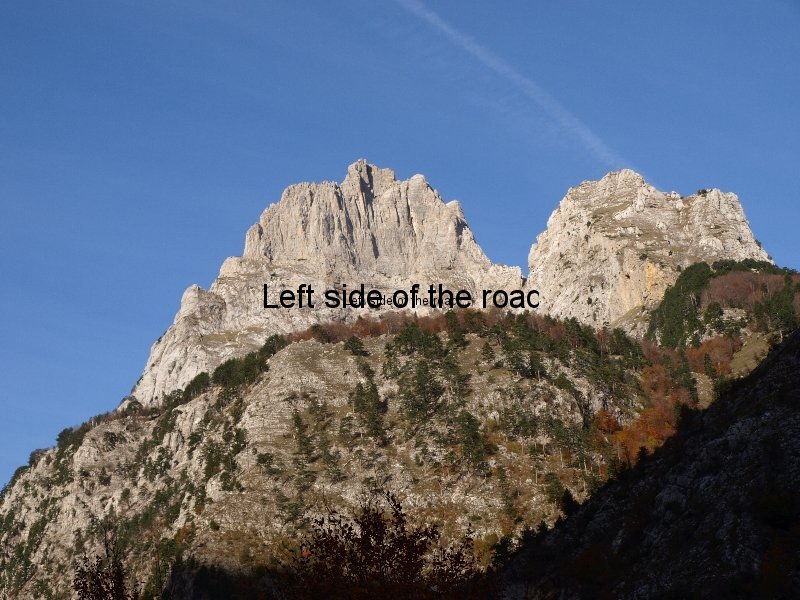

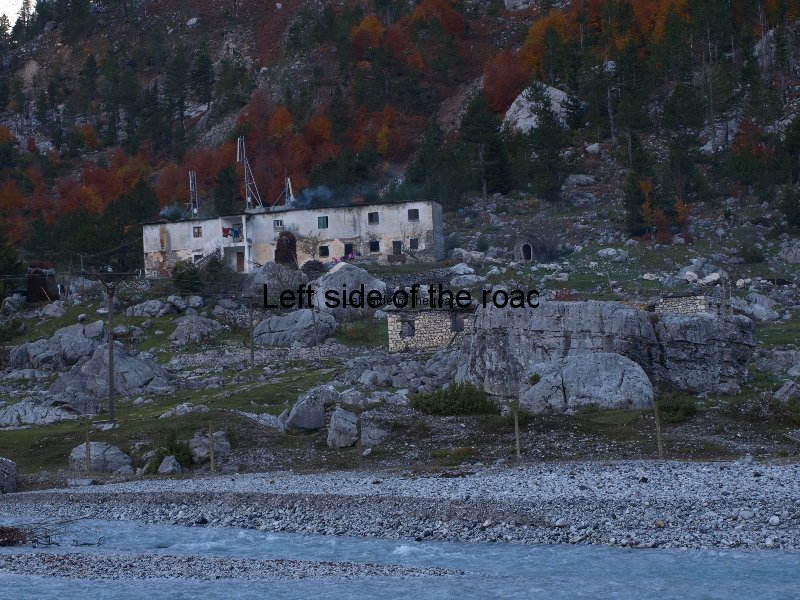

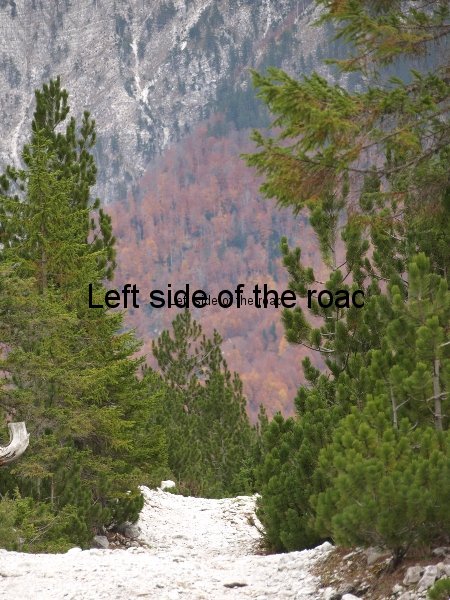

One church that I visited that did seem to have had some element of care lavished upon it over the years was in the same village of Dhërmi which I’ve mentioned above. This was Panagia Monastery Church – Mother of Christ – perched high up above the old town.

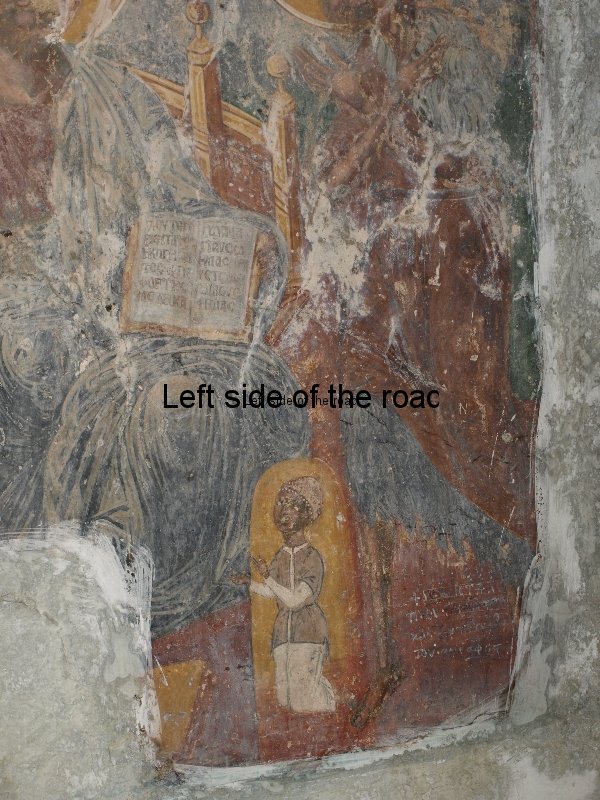

When I say ‘care’ that is all relative. Even though in a better state than some of the older churches the space at the back of the church resembled something closer to a garden shed than a church, and the ancient mural that covered the whole of the back wall had a home-made ladder (the sort you see in an orchard) leaning against these fragile images. I’m not one for arguing that these images should be destroyed but at the same time I do believe there’s a certain responsibility incumbent upon the local people not to damage them by carelessness and neglect. If they don’t take care why should the rest of society come in a pick up the bill for restoration?

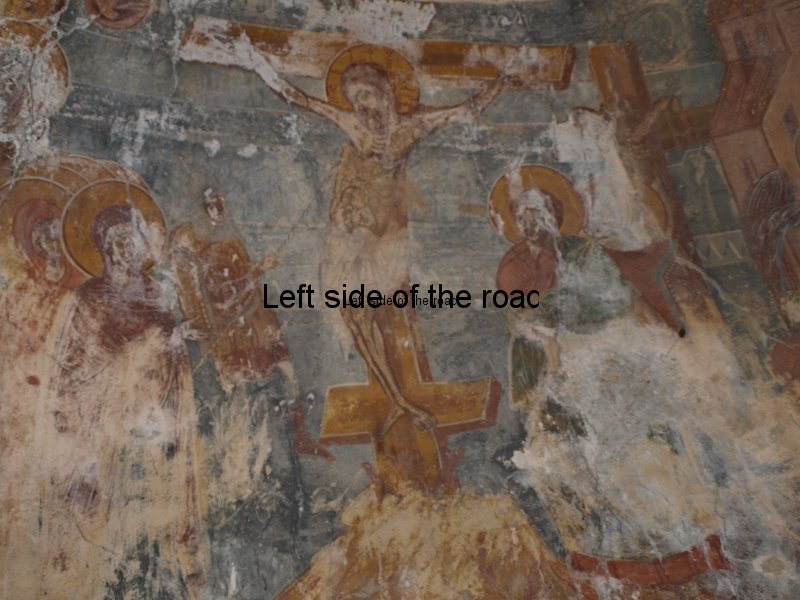

It was on this wall that I saw some of the most interesting images in a Greek Orthodox church so far.

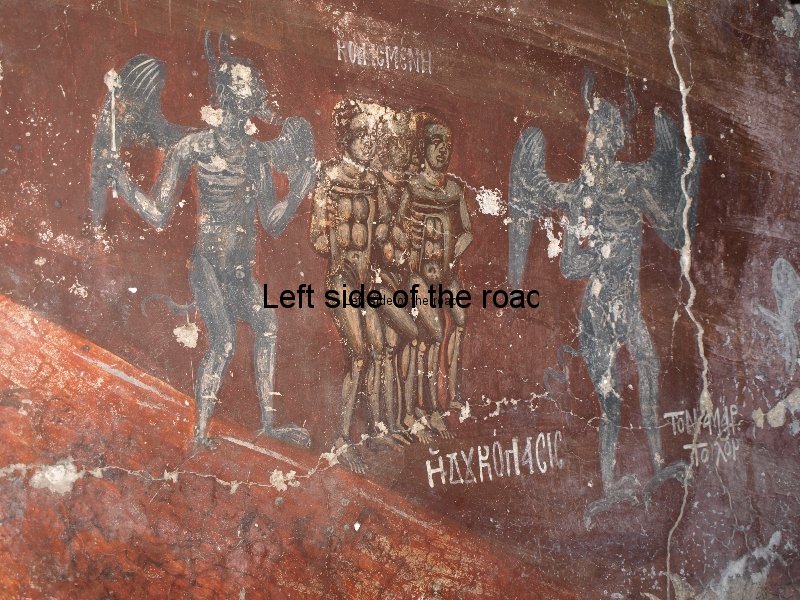

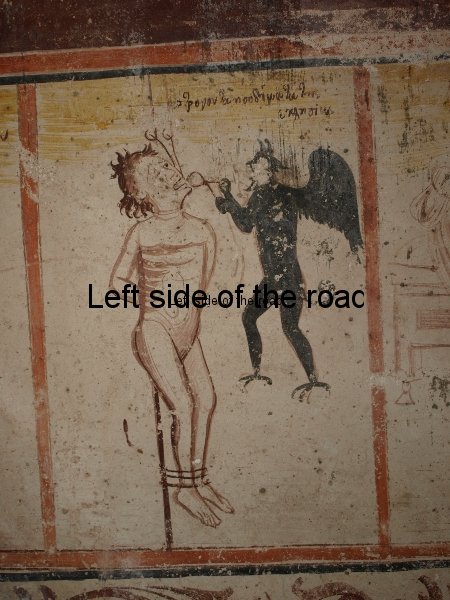

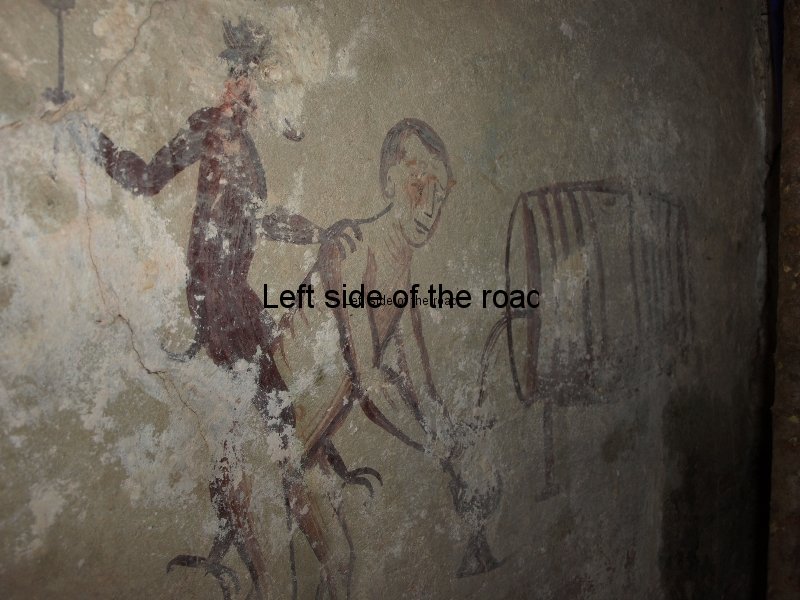

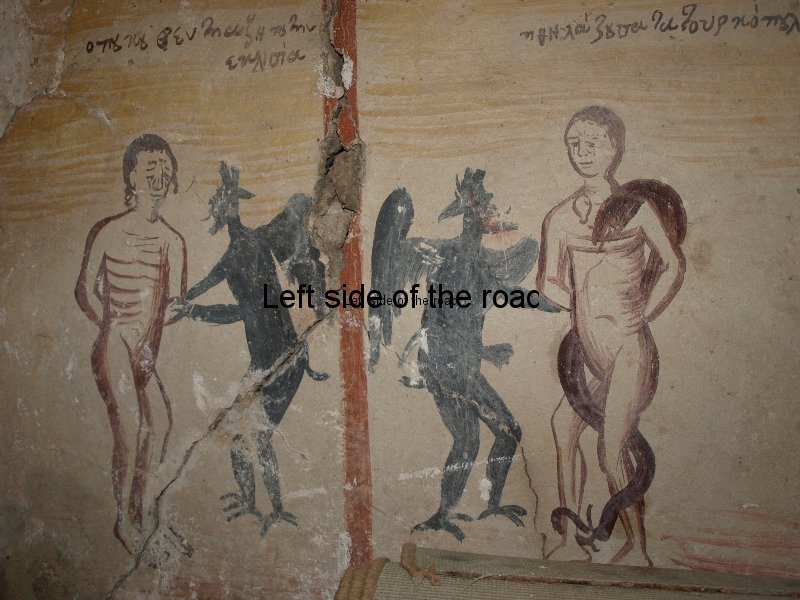

I’m always on the look out for the unusual, as I said above. What has particularly attracted me about many of the paintings in Romanesque churches is the way that ignorant, frightened, superstitious and gullible people thought of the afterlife. Placing these images in churches was obviously a process of social control. If you were faced with such horrific images of perpetual torture by horrendous, devilish creatures you were less likely to buck against the existing order. The images might be different but religion still plays that pivotal role in most societies – hence the atheist campaign in Albania.

So what is Hell like? I’m always on the search for any clues just in case I’ve got it all wrong and there is a God, there is an afterlife and there is a Heaven and a Hell. Because if I have got it wrong I’m going to Hell for sure – and wouldn’t even contemplate going to Heaven.

If there is a God then these images are not just from the imagination of man – I don’t think many women were painting church murals in the past. They must come from some inspiration from the Almighty and therefore must be an accurate record of the fate to befall all of us sinners.

And that being the case I’m always glad that God has a sense of humour as well as being prepared to cruelly place many of us through torments and agonies for eternity. I particularly like the image that, I assume, depicts what awaits a drunkard when he enters Hell, being forced to drink from a never emptying barrel. I know some people who would rather see that as a depiction of Heaven.