Arch of Drashovice 1920

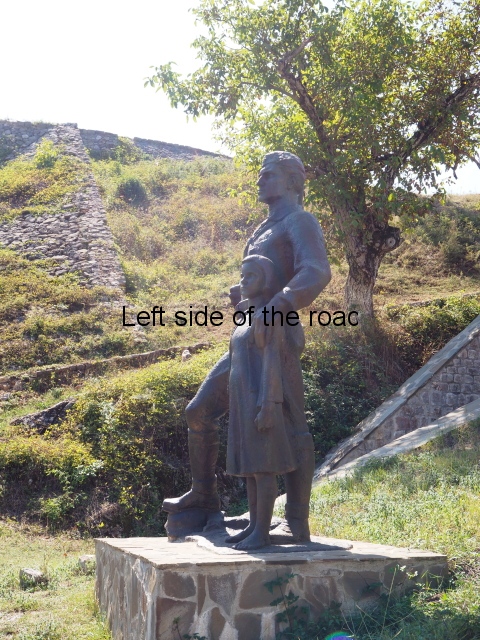

The magnificent Arch of Drashovice is such an amazing structure with so much to tell us that I’m breaking the description up into three parts. This is the second and addresses the images relating to the battle in 1920 against the Italian invaders, a battle (and war) fought by an irregular army of peasants, workers and intellectuals against a heavily armed imperialist force.

I plan to describe the sculpture by starting from the panel underneath the arch and working clockwise to pick up the huge amount of activity and symbolism that’s before us. The two parts of the arch represent two distinctive events but there are some motifs that occur on both sides, another device (the bronze statue being the first) by Dhrami to show the similarities of the battles. There are also images that I have described before on other lapidars, signature images, if you like, of many of the sculptures in this intense period of memorial construction.

First we see just the head of an Albanian male, wearing a qeleshe (hat). He is looking towards the back of the arch, the direction away from all the action. But he’s still part of that action as he has his hand up to prevent the wind taking away his voice as his wide open mouth indicates he is calling for others to come and join the fight. This is a common image, seen before, for example, on the Peze War Memorial.

Almost hidden by his face and hand is an unidentified person and then we have a group of four weapons. First there’s a two-pronged pitch fork, then a scythe, next a hatchet and finally a forearm holding a rifle aloft. This is the arm of the male calling back to others. He wants others to join but he is also in the act of going forward. Partisan, guerrilla wars don’t have the force of a state behind them. There’s no quartermaster able to call upon limited resources. It’s no use them complaining to the government if they think they have been ill-equipped to deal with the enemy – as have soldiers from Britain and the USA in their illegal invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan (and will do in whatever country is next on the list).

No, a partisan fights with whatever is at hand. If they ‘want’ a gun, or some other sophisticated weapon, then they have to take it off the enemy. The choice of agricultural implements also shows that this was a battle fought mainly by peasants and the people from the countryside. Their depiction also indicates that this could have been a battle fought in close proximity, where no quarter was asked or given and was likely to have been a desperate and bloody affair.

Below the weapons is the full body depiction of a woman, wearing the kapica head covering and a long peasant dress of the period. On her feet are sturdy sandals. Her left hand is supporting the crumpled body of a male fighter, who has obviously just been shot and on the point of death, with his eyes closed. He is unshod, footwear giving an idea of the social position of the actors in these dramas, and is wearing the clothing of a peasant, with no military aspects whatsoever, as if he had just come from the village to the battle. His right hand is holding on to the rifle strap and his left just touching the wooden butt of the rifle. The reason he hasn’t dropped his weapon is that the woman has a tight hold of the barrel in her right hand. What is interesting about her stance is that she is not looking at the dying man but looking to where the fighting is taking place, a look of determination on her face. She will take care of the wounded if she can (although he looks like it’s the end for him) but she is also a fighter ready to take up the weapons of the fallen. This looks like the same type of rifle, a Carcano M1891, that the figure in the bronze statue is holding. Just below her left foot is the name ‘M Dhrami’ and the date ‘1980’. (Not all the lapidars have the name of the sculptor/s but it’s worth looking nonetheless.)

In front of her are a group of people either already fighting or joining the battle. Close to her, and with the dying man almost falling on him, is a male fighter, kneeling. He is bare-headed and has his rifle up to his shoulder, already firing. His dress is more military in style than the dying man, with more elements of a uniform. He has an ammunition belt around his waist and a pouch hanging across his back. On his feet are sandals and he wears gaiters over his shins.

Above him and at the same level as the woman are three males. They are not yet involved in the battle but there is a sense of movement in their stance as they rush to the front. Again they look like a mix of soldiers and volunteers. The male we see most of has straps across his chest and is holding his rifle with his left hand with the top part of the barrel pressed against his shoulder. On his head is a qeleshe. Of the other two one is also wearing a qeleshe but the other is bare-headed, and again looking more like a civilian. The one with the hat also has a bushy moustache, something which is quite prominent in images of males of the 19th and early 20th centuries. We don’t know if they are armed or not but they are going anyway. This presentation of individuals in groups of three is quite common in Dhrami’s work (something I will look at in more detail in the future).

Finally, on this inside panel, and further up, are two other fighters, a male and female. She is dressed in exactly the same way as the first woman, although we only see her head and shoulders. Her rifle is up to her shoulder and she is aiming along the barrel. We can only see the head and shoulders of the male above her but he is wearing a qeleshe and what looks like a sheepskin coat – it can get cold in the mountains. He’s holding a rifle but it is not yet in action.

I haven’t come across actual statistics but already, on this first part of the telling of the 1920 battle, we get the indication that women were involved in the actual fighting against the invaders. About 16% of the partisans in the 1940s were women but their active involvement probably goes back to the early days of the 20th century, the most famous and often referred to being Shota Galica. She wasn’t at Drashovice as she was fighting further north at the time.

Stylistically we can see that the story starts low and moves further up the stone as it unfolds clockwise. This means that the main panel, the one facing the road and the village itself, is a hive of activity, images covering more than 50% of that part of the arch.

Dhrami uses a few clever devices to move the action through a 90 degree plane; the flowing cape of the partisan destroying the cannon; the broken cannon itself; and the shoulder of one of the fighters which appears just above the cape. This has the effect of making the scene appear to be as one, with the first group seeming to be slightly behind, but still part of, the main action.

Perhaps the most striking figure on this main panel is the fighter with the cape. In that figure we have a number of symbolic references. Albania is normally depicted as female, as in Mother Albania, the statue that guards over the (now desecrated) Martyrs’ Cemetery in Tirana. Here the country is depicted as male.

The cape is attached to his body via four straps which are held together with a clasp in the middle of his chest. On this clasp is the double-headed eagle and by adding this symbol the cape then becomes a flag, which all those who are not yet in the battle are running towards. It spreads out behind him, a clarion call to all patriots. He’s a big and strong man, though not necessarily young, sporting both a beard and a moustache. He’s wearing a qeleshe on his head, he is a peasant, the rock on which 1920s Albania was built.

And he’s doing the impossible, pulling apart a mountain cannon with his bare hands. His right hand is gripping the opening of the muzzle and his left on the outside of the barrel to break the cannon itself from its fixing. His success in achieving the impossible is the broken fixing and wheel in front of the kneeling fighter already described. Also broken away is the flash guard. He’s doing all this bare-foot and although we cannot see the left foot we can assume he is using that to press down on the gun and get more purchase. His bare right foot is crushing the crown of the coat of arms of the Italian monarchy, breaking it away from the shield of Savoy (which was a white (Greek) cross on a red background).

So here we have ‘Father Albania’ destroying, with his bare hands, the military might of the Italian Army and in the process seriously damaging the power of the Italian Monarchy and breaking any hold it might have over Albania. (The fact that the self-proclaimed ‘king’ and despot, Zogu, was to sell out his country to the Italian Fascists before the decade was out is neither here nor there. Such cowards and opportunists are always with us and it was only in 1944 that Albania was able to achieve the real independence that so many had been struggling to achieve for centuries. The fact that the present day rulers of the country have thrown away that success should also not come as surprise. Sycophants, country-sellers and forelock-tuggers are always queueing up to fight over the crumbs from imperialism’s table.)

A further possible reference here is to the guerrilla fighter of the time of the wars against the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, Mic Sokoli. He went down in legend as dying by pressing his own body against the Turkish cannon at the battle of Silvova in April 1881 (a deed for which he was later awarded the title ‘hero of the People’).

Now things really start to get busy with a lot of activity as the battle heats up with more Albanian patriots arriving to crush the Italian invaders. Behind the gun destroying hero are three faces, two over his left and one over his right shoulder. One is armed with a scythe whilst we can see the ends of two gun barrels. They are not yet fighting but are on their way, determination etched on their faces.

Going further up we see the upper torso and arms of a single peasant fighter. He has a large hatchet in both hands but whilst his stance is one of attack he is looking back over his shoulder, both leading by example and calling for others to join the fight – we can see his mouth is open. Once you have the tactical advantage in any battle lack of commitment can lead to victory morphing into defeat.

Further upwards still and moving into the centre of the facade there is a group of three males. Due to their scale, stance and position these would seem to be a command group. The very nature of the countryside means that this group would likely to have been in the hills, looking down on the fighting and getting an overall picture of the situation. Whilst most of the individuals in the 1920 story are dressed in the clothing of the countryside the male on the right is dressed in town clothes, perhaps representing the small working class or the pro-independence, intellectual element within the country. He is clean-shaven and bare-headed whilst his two companions are moustachioed and wear qylafës (woollen hats). His left arm is bent and his hand clasps the lapel of his jacket. In his right hand he holds the top of the barrel of a rifle, the butt resting on the ground. He is not looking at the action but to some location in the distance, down the valley. Around his waist he wears ammunition pouches so is ready to fight but not doing so at the moment.

The man behind him is wearing the traditional countryside type of clothing and his right hand is on a shoulder strap of something we cannot see. The third of the group is not armed, as far as we can see, as he is the standard-bearer, the flag with the double-headed eagle fluttering above the three of them. These last two are also not looking at the battle below, more they are looking at the viewer.

Now almost at the top of the action on this part of the monument is a group of four males, all dressed in traditional clothing of the countryside. The male on the extreme right is in full figure and is clean-shaven. We can see he is wearing a fustanella, together with the tsarouhi style shoes, hobnailed and with the ball of sheepskin at the toe (which is also depicted on the Education Monument in Gjirokaster) and a qylafë on his head. There’s an ammunition belt across his chest and his cloak flutters out to his left. He seems to be climbing up hill but is looking up into the sky. He holds a rifle by the trigger mechanism in his right hand and his left hand is clenched, in anger, determination or victory, the 1920 version of the high five? We’ll see why that might be the case in a short while.

Behind him is another male wearing a sheepskin xhakete. He’s bare-headed and sports a moustache. His right hand is gripping the straps across his chest and in his left hand he holds out his rifle in triumph.

The other two males in this group are close together and are situated just above the fluttering national flag of the standard-bearer. Both have their rifles up to their shoulders and are firing downwards. This is almost always the case on Albanian lapidars. The country is mountainous and throughout history the partisans and guerrillas have used that to their advantage and this firing downwards is symbolic of that way of fighting. It also represents the moral and political high ground.

As we come back down along the left hand edge of the panel we see why the two fighters on the right hand side were so triumphant. Here we see a fighter biplane but it’s not attacking it’s falling from the sky, a plume of smoke following it as it crashes. The cross of Savoy is on the tail fin. This has just been shot out of the sky by the marksmen in the mountains. It’s difficult to identify exactly what make of aircraft but it was probably something left over from the First World War as there didn’t seem to be much development of military aircraft in the country until Mussolini came to power in 1922.

As the biplane falls to destruction in the background the next group on this left hand side is a group of five males, all with rifles to their shoulders and firing in the same direction. They are on the same level as the command group but as we come back down the panel the fighting gets more intense, more fierce and more hand to hand. If this is an accurate description of what actually happened during those days in 1920 then it was something that repeated the close quarters fighting of the trenches during the 1914-18 war. As has now become a pattern these five men represent the various areas of the country and class background already seen, with traditional clothing to something more akin to an early 20th century military uniform.

Moving again to the centre there’s the image of a peasant woman. She’s wearing the kapica headdress (seen earlier) and over her dress a sheepskin jacket. Her left hand is resting on her chest and her right hand grips the barrel of a rifle. She’s looking down the valley and has a concerned look on her face. I’m not really sure what she is doing or represents. She’s the only woman on this panel which shows the battle in full swing but she’s not actually doing anything. She’s looking towards the images of the 1943 battle but I don’t know if that’s significant.

Below her we are right in the front line. Here we have four males involved in hand to hand combat but they are all doing so in a different way. On the far left hand side the partisan is pulling apart the Italian barricade with his bare hands. Whilst he holds his rifle by the barrel in his left hand he places his sheepskin jacket over the barbed wire and wooden crosses so as to be able to get over and take the battle to the enemy. Along this protective barrier we can make out the barbed wire that was used to make the barrier that more difficult to breach – but it doesn’t seem to be that effective. He’s wearing the typical peasant shirt, with wide sleeves and the woollen hat.

Next to him, on his left, is a somewhat unusual image of a male fighter. In his right hand he holds a meat cleaver but even though he’s right in the middle of the action and so meagrely armed he’s looking to his back as if looking for more support. He’s dressed as if from the town and perhaps wondering what brought him to such a situation.

To his left is the only Albanian with a modern weapon in this dangerous part of the action. Here a peasant has his rifle in a position to fire, the enemy being literally only a few feet away. Around his waist he has spare ammunition, if he survives such close combat. The last of this group of four is also a peasant in traditional country dress but he only has a wooden, three-pronged pitchfork as a weapon – although he appears to be using it in a very effective manner, it is raised high and he’s about to bring it down on the enemy with all his strength. One of these last two is wearing sandals, the other the opinga shoes.

This part of the tableau shows the very moment of the Albanians breaking through the Italian defences as beneath their feet we can make out the broken wood, with the pieces of barbed wire attached.

We have already seen that everything that could be used as a weapon had been brought into play and this only goes to demonstrate the nature of the war – a people’s war against the invader, whatever might be the cost to individuals.

These are the last of the Albanians on this part of the sculpture.

The remaining characters are seven of the Italians. Their stance, body language is the complete reverse to that of the Albanians. The Albanians are on the attack, they are confident, they are sure of themselves, however badly armed they might be. They know they are going to win as they are defending their own land whilst the invader is merely a paid soldier doing the bidding of a misguided monarch.

So all the Italian soldiers are falling back, they look weak, they look on the brink of defeat. They have nothing further to bring to the battle. Their superiority in military technology has shown itself to be ineffective, the artillery is shown as being broken up and the air power is crashing to the ground.

These soldiers are from the Bersaglieri corps, recognisable by the capercaillie feathers on their helmets. (This is the corps of the Italian army whose ‘fanfara’ (band) play on the run, an image you might have seen at some time in the past.) This is not their finest hour.

Of two of them we can only see the helmets, both bowed either in submission or to protect themselves from the meat cleaver that’s only a matter of inches away. Two are still firing but looking desparate as the Albanians break through their lines. A bearded officer has fallen back and is sitting on his haunches. He still has a rifle in his right hand but he’s not attempting to use it to try to prevent the onslaught of the enemy. Immediately to his left a soldier has both hands in the air, in the act of surrender, and to the officer’s back there’s slumped and lifeless body of a dead or wounded Italian.

An interesting novelty can be seen between the heads of the two bowed helmets and the two still fighting. Here there’s an entrenching shovel pointing upwards. These were used as auxiliary weapons when it came to close combat and would seem to demonstrate how desperate the battle was for all concerned, grab anything for protection or assault. Just behind that tool it’s possible to make out the muzzle and barrel tripod of a light machine gun, now no longer effective or in use.

This whole battle scene encompasses the war, the many battles and the final victory of the Albanians over the Italian invaders, who were soon to leave from the near-by port of Vlora for the trip back home.

Although I can’t say for sure research has led me to believe that (based on their areas of activity) the Albanian Commander was Sali Vranisht, in command of forces from Lumi i Vlores, and the commander of the Italian forces a Major Guadalupi.

Background to the war.

Here it’s perhaps worth while mentioning that the defeat of the Italians in their effort to divide and dismember Albania in 1920 wasn’t just the defeat of that nation but of the overall plans of western imperialism and it designs on the Balkans. It’s no accident that the Italian invasion took place almost exactly a year after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, which officially ended hostilities between Germany and the Western European powers, and was where the so-called ‘western powers’ sought to divide the spoils of the defeated enemy, especially the Ottoman Empire.

Conflicts between the western imperialist powers and Russia had meant that the Balkans were an area of concern, conflict and intervention for most of the second half of the 19th century and those interests were revived after the carnage of the First World War. The 1917 October Revolution in Russia added another dimension to this long-held policy of limiting and squeezing, now a proletarian led, Russia. Although through the battle of Drashovice (amongst others during the short war) western imperialist interests were set back that didn’t mean that those aims were forgotten. Within a year of the ending of the Second World War the British used military might in an attempt to intimidate the new People’s republic of Albania.

Yet more vandalism?

When I had the opportunity to visit this magnificent example of socialist realist art for the first time in May 2015 I left pleased that I had visited a lapidar that had survived without any significant damage due to vandalism, whether officially sanctioned or not. Yes, there was a little bit of paint graffiti but that seemed the work of bored children with a pot of paint. It wasn’t till I started to really look at the pictures closely I realised something was amiss.

This is a remarkably symmetrical piece of work. Dhrami is constantly drawing parallels between the two events that were separated by those 23 years. This will become clearer when I describe the images of the battle against the Nazis in 1943. Symmetry is everywhere: the location of the images that tell the two stories; the location of the slogans; the location of the symbols; the positioning of the players or incidents that Dhrami is depicting; down to the height of the carvings in the stone. One side is a mirror image of the other, only the weapons and the clothing are different.

It is the height difference that shows that something has been changed. When, why, by whom or why I presently have no idea. What makes this vandalism even more confusing is that it has been perpetrated on the 1920 side of the arch. It’s normally the Communist emblems and symbols that have been attacked by mindless fascists but here it has something to do with a pre-Communist period.

If you look at the whole arch you will notice that the images on the right hand side go up a metre or two higher than they do on the left. One of the aspects of this piece of work that is noticeable is the way Dhrami merges the images in the story he wants to tell. Figures overlap, we rarely see full figures as another story needs the space. However, a closer look at the top of the carvings of the 1920 story show something different.

The merging of the images seems to stop with the four males fighters, and the very top of the design is the celebratory raised gun after the shooting down of the biplane. But there’s something further up. Am I the only one to make out a head, almost at the centre, with possibly something like a gun barrel pointing downwards? To me it appears as if a small group has been erased. If you were to draw a horizontal line across the void under the arch the top of this group would be at exactly the same height as the top of the highest group on the right hand side. I’ve searched but the only picture I’ve been able to see that was taken before 1990 of this arch is of such poor quality that it’s impossible to see what (if, indeed, anything) was there.

The carvings are on these two sides of the four of the arch but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing on the other two.

Carrying on in a clockwise direction, the next panel, north facing, tells the story, that we have already seen in pictures, in words together with symbols that had meaning at the time, that is 1920.

Quite high up the Albanian two-headed eagle seems to emerge from the stone. This is cleverly done as we know exactly what it is without the whole creature being shown. Whereas the left side of is in relief text takes the place of the feathers on the right.

The text reads:

Evropa shkruajnë e thonë, ç’është kështi si dëgjojmë, bënet dyfek në Vlorë, shqipëtarët po lëftojnë, me një mbret dyzet milione. Po me se lëftojnë vallë, me sëpata me hanxharë, dyfeqet lidhur me gjalmë, fishekët në xhep i mbajnë, në tri ditë bukë hanë.

(This is written in Tosk Albanian, so slightly different from what you’ll find in most dictionaries.)

This translates to:

Europe will write and talk about, with rifle fire being heard in Vlora, the struggle of the Albanians against a king of a population of forty million. How they fought with axes, scythes and rifles, held together with string, keeping their bullets back and they eat bread once in three days.

The reference to ‘forty million’ is significant if you remember that even during the National Liberation War of 1939-1944 the population of Albania was still less than one million. Although the road to Vlora, even today, takes about 45 minutes the city is only a few kilometres as the crow flies – the problem is the mountain range in the way. It’s very likely that inhabitants of the coastal town would have heard the sounds of gunfire reverberating in the Shushicë valley.

Poking up, just behind the head of the eagle on the right side are the tops of the weapons used in 1920, that is, an axe, a scythe and an old rifle.

Finally, on the last face, a huge left hand is tightly gripping a rifle close to the muzzle. The forearm disappears and becomes the number 1920, in large numerals. To the left are the dates between which the battle was fought:

5 qershor 3 shtator – 5th June 3rd September

This is followed by the words:

Lufta e Vlorës në vitin 1920 është një epope e shkëlqyer e fshatarësisë patriotike të Vlorës e Kurveleshit, Tepelenës e Mallakastrës e të gjithë popullit shqiptar që hodhën në det pushtuesit italianë.

Which translates as:

The Vlora War of 1920 is a remarkable epic of the patriotic Albanian peasantry from Kurveleshi, Vlora, Mallakastra, and Tepelenë who drove the Italian invaders into the sea.

As this is such a complex and detailed lapidar I intend to describe its complexity over the course of three posts. This is the second of the three. The others can be found under the name of ‘Arch of Drashovice – Introduction and Statue‘ and ‘Arch of Drashovice 1943‘.

Getting there:

I’ve found the best place to pick up a furgon that goes along the Shushicë Valley is by waiting beside the road in the square opposite the Vlora Baskia on Rruga Perlat Rexhepi (the Historical Museum is at the Vlora end of this road). Other furgons leave from this point but you want a furgon that comes the centre of town. Just flag down any one that comes from that direction (possibly going to Mavrovë or Kotë) and ask for Drashovice.

GPS:

40.44681902

19.58655104

DMS:

40° 26′ 48.5485” N

19° 35′ 11.5837” E

Altitude:

64.2m