‘Mother’ – Mumtas Dhrami – 1971

More on Albania ……

1971 National Exhibition of Figurative Arts – Tirana

The article below was first published in New Albania, No 6, 1971. It discusses the general idea of art in a socialist society, how the Albanians saw ‘Socialist Realism’ with mention of a handful of works (out of 180) that were displayed at the National Exhibition of Figurative Arts in Tirana in the autumn of 1971.

Emphasis, so far, in the pages on this blog related to Albanian art, has been placed on the Albanian lapidars – public monuments. There have been a few reasons for this: they are often large and out in the open, and therefore accessible to all at all times; some of them all under threat of decay from either neglect and/or vandalism – a number of important ones have already been destroyed by reactionary forces within Albanian society; they embody a uniquely Albanian approach to such monuments: and, even if in the public domain are often ignored – strangely people walk past works of art everyday (and not just in Albania) without taking notice of what they are passing or the significance they might have in the country’s history.

But ‘Socialist Realism’ in Albania was not restricted to the public sculptures and a great deal of material in all forms was produced from after Liberation in November 1944 until the capitalist supported reaction was able to re-take the land of the people for the benefit of exploiters and oppressors in 1990. However, these numerous works of art, that used to be part of the people’s heritage, are now under the control of the enemies of such political statements in oil paint and water-colours (as well as stone, bronze and wood). Many museums and art galleries have been closed and (no doubt) many works of art destroyed by the ignorant reactionaries or stolen by the opportunistic and avaricious. An obvious example is the looted museum in the town of Bajam Curri, in the north of the country.

However, there are still a few museums that still display examples of Socialist realist Art. Apart from the National Art Gallery in the centre of Tirana (which always has a permanent exhibition of art from the revolutionary, socialist period) a visitor to the country could investigate the modern art gallery close to the Bashkia (Town Hall) in Durres; the museum and art gallery in the centre of Fier; and the small gallery in the town of Peshkopia.

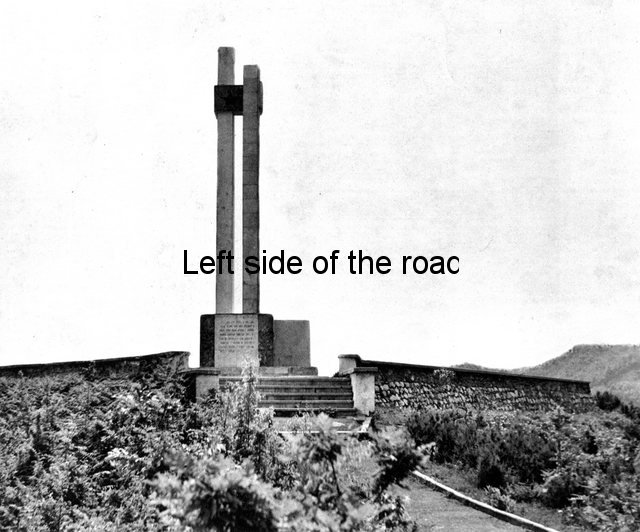

(Unfortunately I’ve never seen the statue of ‘Mother’ by Mumtaz Dhrami, that heads this post. He was, and still is, one of the most renown Albanian sculptors and such a piece of work demonstrates a very Albanian approach to sculpture, chunky and solid. I hope it still survives intact (but fear not). At the same time I have no knowledge either way. Other creations of Dhrami are: the magnificent Arch of Drashovice; Education Monument in Gjirokastra; Mother Albania at the National Martyrs’ Cemetery; the (now virtually destroyed) Monument to the Artillery in Sauk; the large monument to Heroic Peza, at the junction to the town on the Tirana-Durres road; and the War Memorial in Peza town itself.)

(My notes/comments are enclosed in italised square brackets [note/comment])

Living colours

by Andon Kuqali

The feelings, emotions and thoughts of the working man, the master of the country, the new man of socialist Albania is the content of this year’s National Exhibition of Figurative Arts. The paintings, sculptures, drawings, and designs exhibited, aim at expressing this content through an art characterized by the truth, the reality of life.

Since the 1971 National Exhibition of Figurative Arts was to be opened before the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the founding of our Party and on the eve of its 6th Congress, the artists chose themes for their works from the history of the Party and the Albanian people during these 30 years, as well as from our revolutionary traditions, themes from the struggle and work to build our new socialist society. As a matter of fact, today even the most modest landscape or still life embodies this new content, because it exists in the very life of present-day Albania.

What strikes the eye in this Exhibition is that the paintings, sculptures and drawings have more light, more vigorous colours, more varied expressions of artistic individuality than those of the previous national exhibitions. This is important because national exhibitions in Albania are a sort of summing up of the best creative activity of our artists during two or three years, thus they show the course of development of our art at a given stage.

But those colours and variegation of form remain within a realist imagery. Turning away from superficial, manifestative compositions, our artists have tried to enter deep into the life of the people to portray it more truthfully, with greater conviction and artistry. The figures of workers and peasants, of partisans or of outstanding people are true to life, simple and this in no way hinders them from being full of virtue, human and heroic at the same time. Even the industrial landscape is presented in its intimate aspect as an integral part of the life of the working man with the richness of original forms and characteristic realistic colours.

The dawn of November 1941 – Sali Shijaku – 1971

[The house where the Albanian Communist Party (later to become the Party of Labour of Albania) was founded in 1941 is the one with a tree to the right of the stair to the first floor. It became a Museum of the Party after Liberation – it might be in private hands now (it definitely isn’t readily accessible.) The letters VFLP written in black on the white wall on the side of the building in the foreground (as well as along a wall at the very top of the painting) stands for ‘Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!’ (‘Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!’), the revolutionary slogan of the Communist Partisans. I don’t know where this painting might be at the moment. I hope it’s in the storeroom of the National Art Gallery. What goes against its public display are the four letters VPLP – modern-day fascists don’t like that!]

Alongside the tableaux in grand proportions which portray notable events from the history of the Party and Albania, or outstanding figures of communists and revolutionaries, the landscape ‘The Dawn of November 1941’ by the gifted painter Sali Shijaku is no less significant and profound. In reality, this is a composition in small proportions in which the great idea that the Party emerged from the bosom of the common people is expressed. It depicts a poor quarter of Tirana as it was, in the midst of which stands the house where the Communist Party of Albania was founded: an ordinary house like the others, except that from the two windows of the ground floor flows a cheerful light which spreads far and wide driving away the gloomy night of the occupation and reaction.

Albanian Dancers – Abdurrahim Buza – 1971

[I don’t know where the original of this painting by Abdurrahim Buza might be at the moment.]

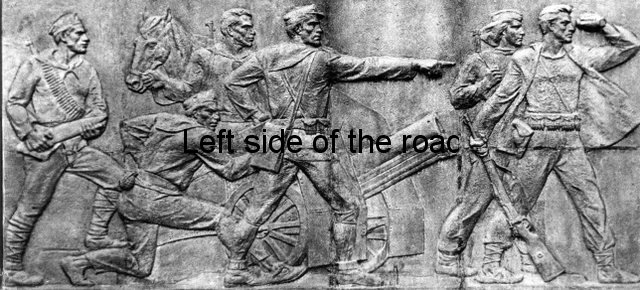

Dancing is the motif of a number of works of this exhibition. ‘The celebration of liberation’ by N. Lukaci, is a composition in sculpture developed with rounded figures, powerful like the beats of a drum and representing a typical folk dance. ‘Albanian Dances’, by the veteran and very original painter, Abdurrahim Buza, is the tableau of a circular dance in which the lively silhouettes of men and women from all the districts of the countryside with all their warmth and colour move freely, expressing the happy unity of all our people.

Planting Trees – Edi Hila – 1971

[This used to be on display in the National Art Gallery in Tirana but not when I last visited in 2019.]

A soft breeze stirs the fragrance of the fresh-dug soil, where girls and boys are planting trees under a blue sky. This is the tableau ‘Planting Trees’ by the young painter Edi Hila, inspired by the actions of the youth, a song of spring for the younger generation of Albania who are growing up happy with a fine feeling for work, a fresh tableau with a dream-like quality, from the vitality of our reality.

The dynamism of the daily life of the workers, their enthusiasm at work in the factory, before the smelting furnace, their chance encounters in the streets, the clash of opinions in which the new man is tempered, are expressed in the strong lines in the series of drawings under the title ‘Comrades’ by Pandi Mele.

Comrades – Pandi Mele – 1971

Like saplings in the bush, the children frolic and romp in Spiro Kristo’s delicately portrayed tableau ‘Springtime’.

The Children – Spiro Kristo – 1966

[Unfortunately I haven’t been able to come across an image of the painting ‘Springtime’ to add here. Until I come across an image I’ll include an earlier painting by Kristo, the charming ‘The Children’. This is still on permanent display in the National Art Gallery in Tirana (as of 2019). In 2016 I took some friends to the gallery and one of them was (literally) shocked to see such a depiction of children on the walls of a national gallery. I didn’t understand his reaction then (or even to this day). he is of an age to have played with guns (and probably destroying the indigenous population of north America on many occasions and children are killing children in school killings in the USA on an almost weekly basis. This painting encourages an idea of national defence, of preparedness against external threat and invasion, and not of aggression which dominates the armed forces of imperialist countries – just consider the wars of aggression in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria and the consequences for the population of those countries.]

In his monumental decorative tableau ‘Our land’, painter Zef Shoshi elevates the figure of the peasant woman, the untiring, hard-working cooperative member, who has won her own rights as a person with tender feelings and priceless virtues, the woman brought up amidst the collective work, in the years of the Party, as the people say. The drafting is connected and dynamic and is permeated by the colour tones of the wheat the soil, and the timber.

[‘Our land’ is another painting I have yet to see, either in actuality or in a photograph. However, this picture of a female skilled worker seems to capture the idea that Shoshi would have represented (confident, aware of her part in the construction of Socialism and a more than equal participant in the new society – a crucial and important aspect of Socialist Realist Art) in his entry for the 1971 National Exhibition of Figurative Art in Tirana.]

These are a few remarks about the 180 works exhibited.

Each painter and sculptor is represented here with works which reflect the world as he imagines it, that aspect of life, past or present closest to his heart, the essence of which he tries to communicate his emotions and thoughts to the viewers as directly and clearly as possible, through the emotions and thoughts of the artist who belongs to the people, an active participant in our socialist society in its revolutionary development. This is the source of the variety of methods of expression of each artist, the special individual features of each and, at the same time, of their common stand towards life. These are the features of socialist realism in Albania, an art, which serves the people and socialism, which aims at being an integral part of the spiritual life of the working class and of all the working people.

[Another painting which was part of the exhibition was one by the painter Lec Shkreli entitled ‘The Communists’. It depicts those Communists who were arrested by the regime of the self-proclaimed ‘King’ Zog just before the invasion of the country by the Italians in April 1939. The person in the foreground wearing glasses is Qemal Stafa – one of the founding members of the Albanian Communist Party.]

The Communists – Lec Shkreli

The article that referred to the 1969 exhibtion was entitled The Revolutionary Spirit in Albanian Painting and Sculpture.

Socialist Realist Paintings and Sculptures in the National Art Gallery, Tirana provides a comprehenive idea of the examples of Socialist Art that have been on display in the National Gallery in recent years.

More on Albania …..