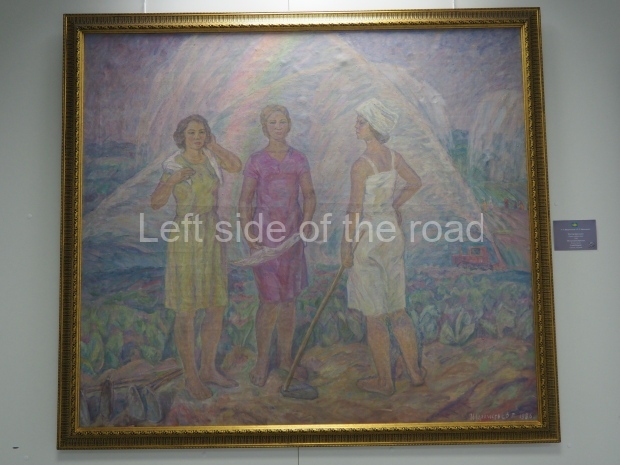

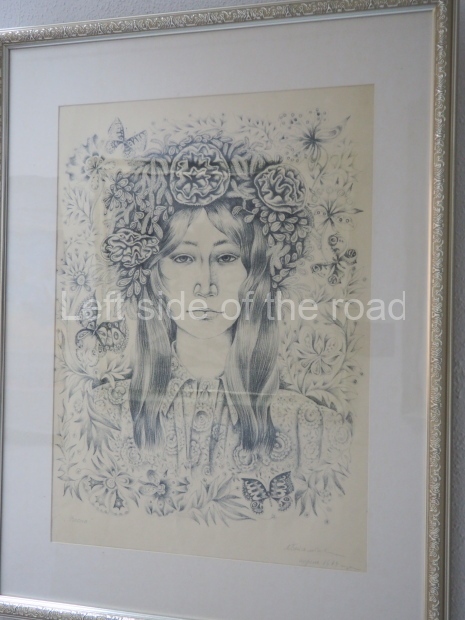

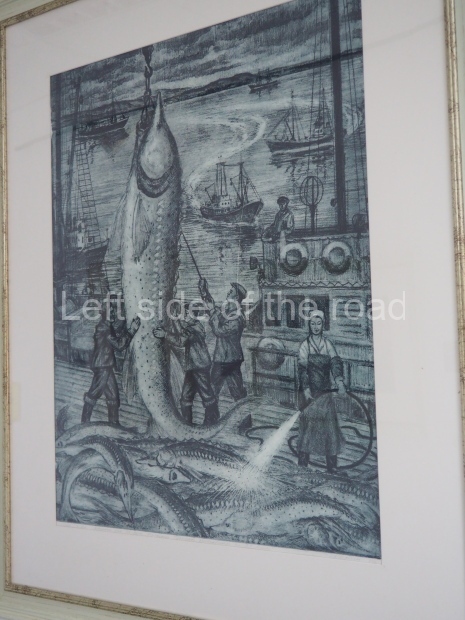

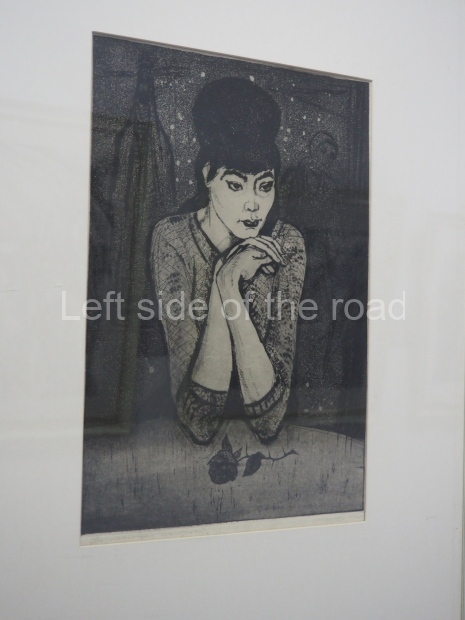

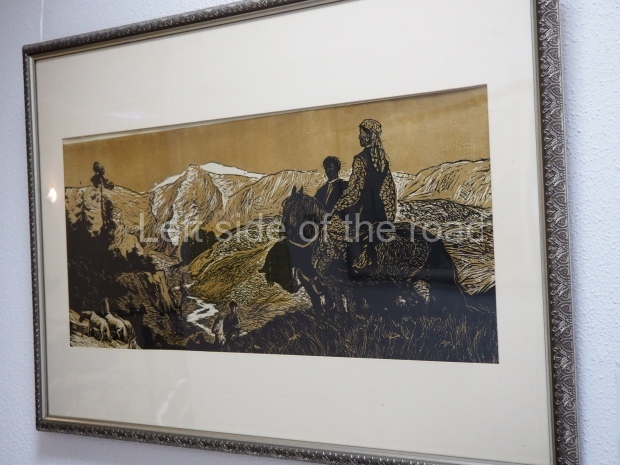

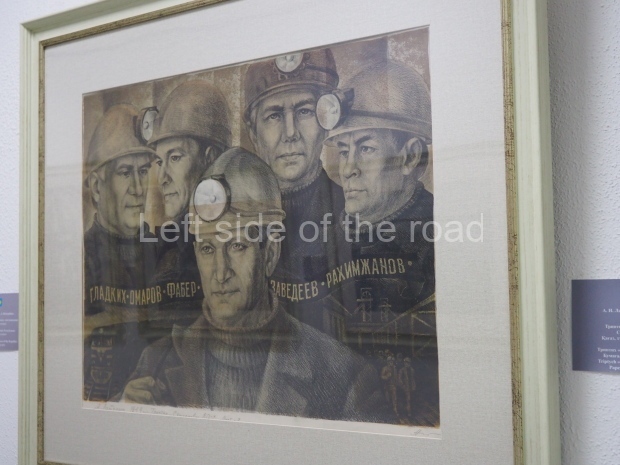

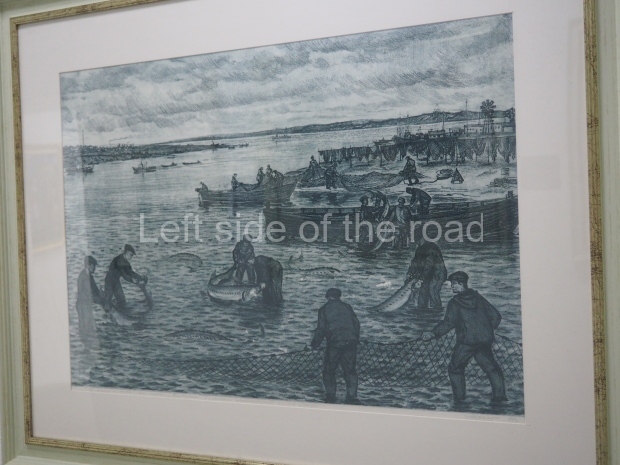

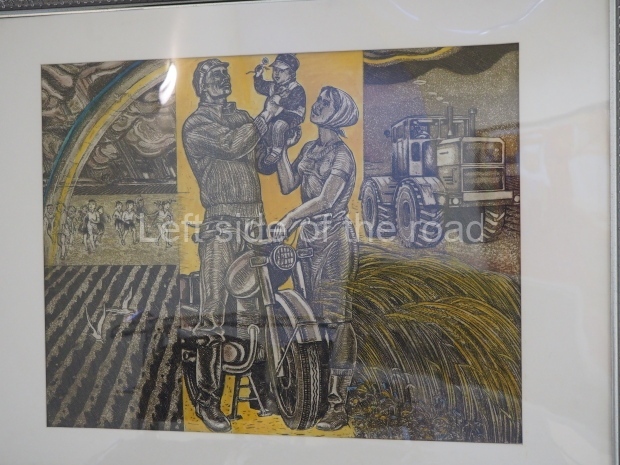

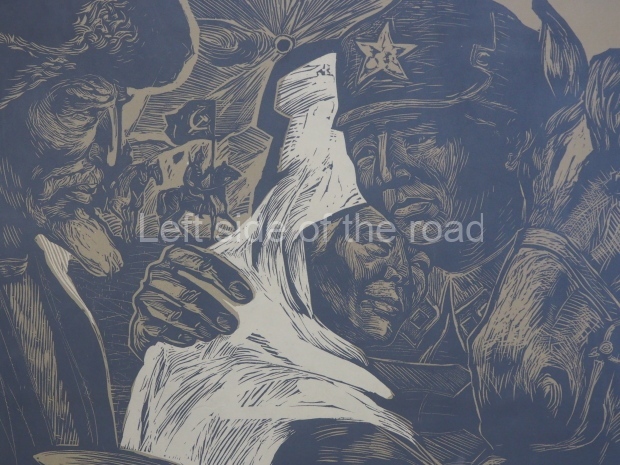

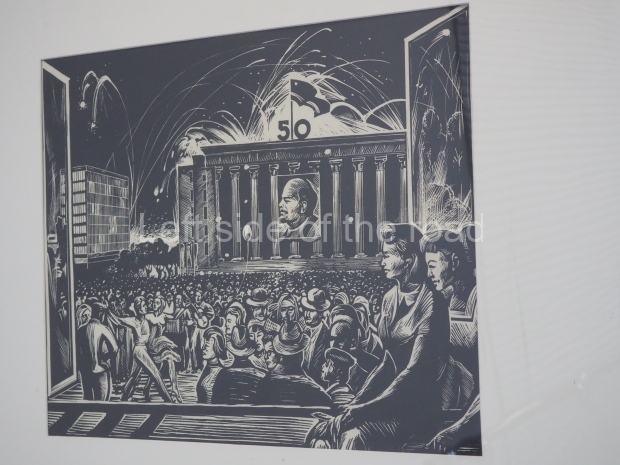

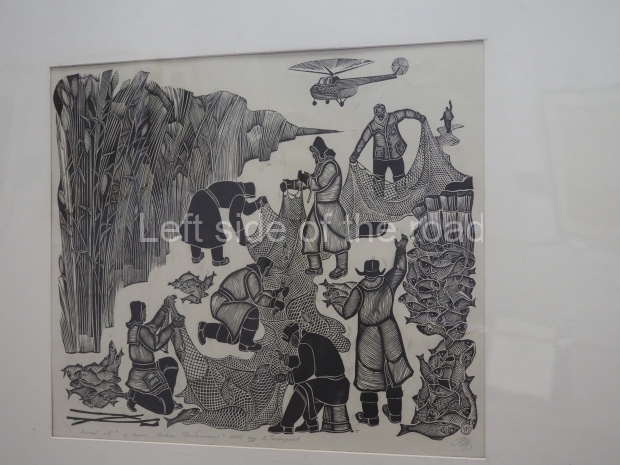

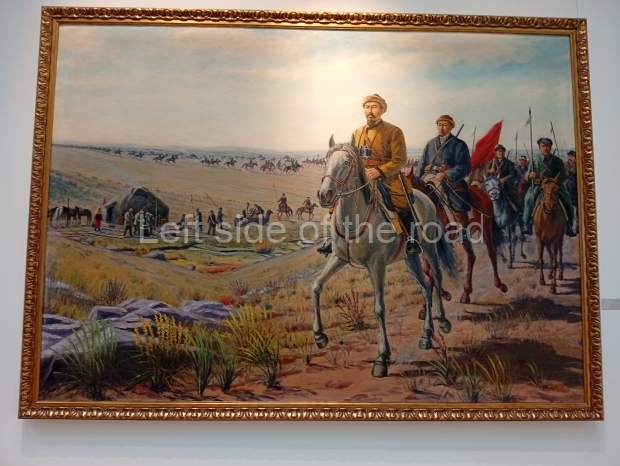

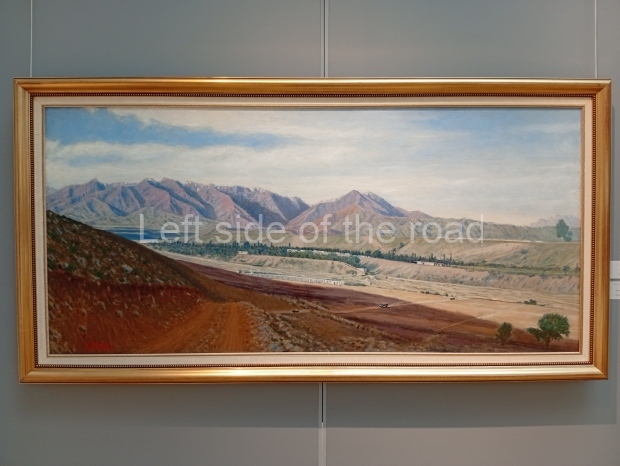

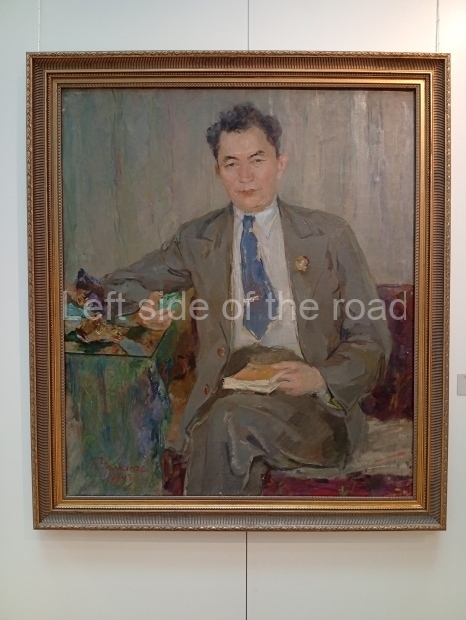

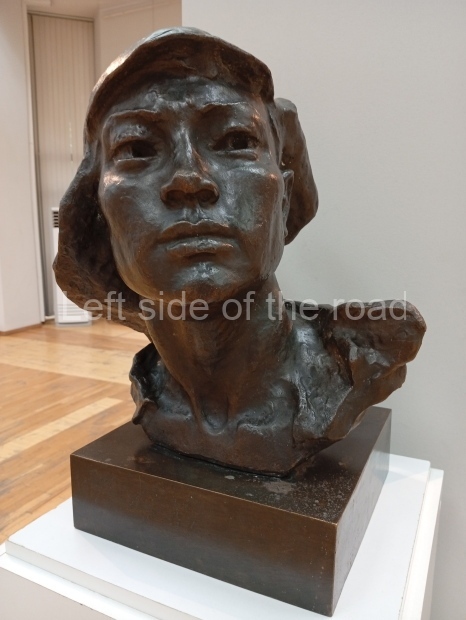

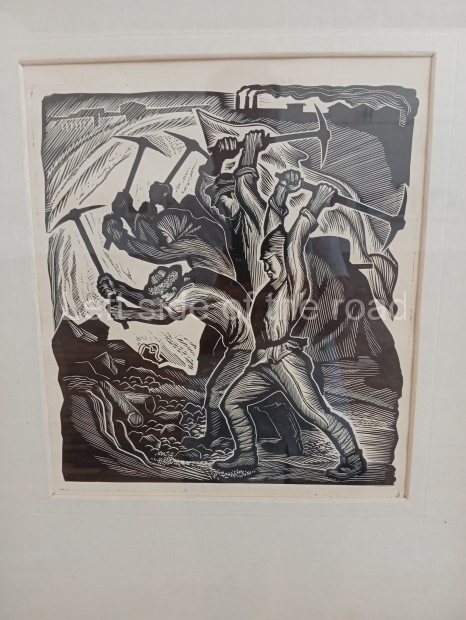

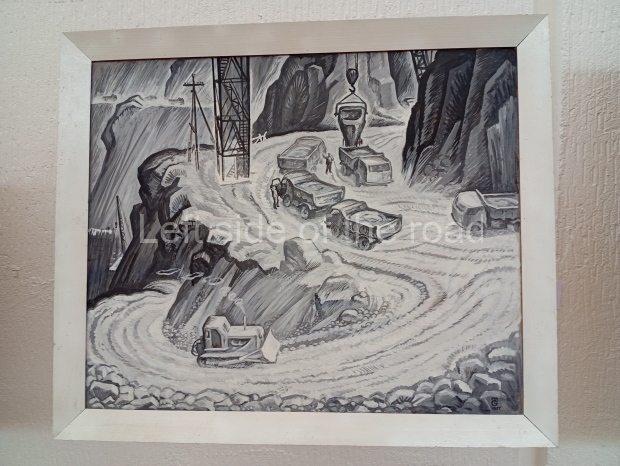

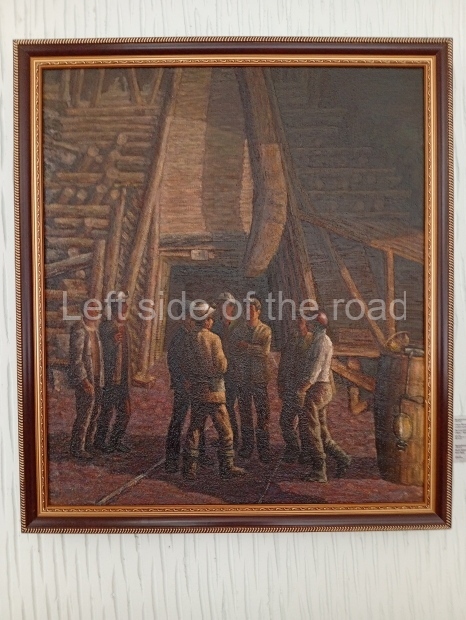

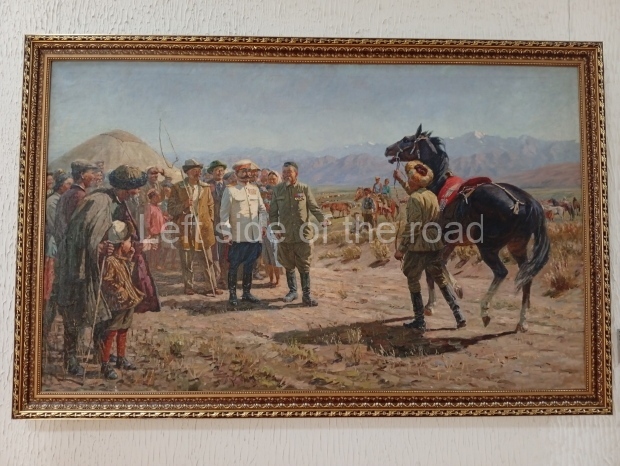

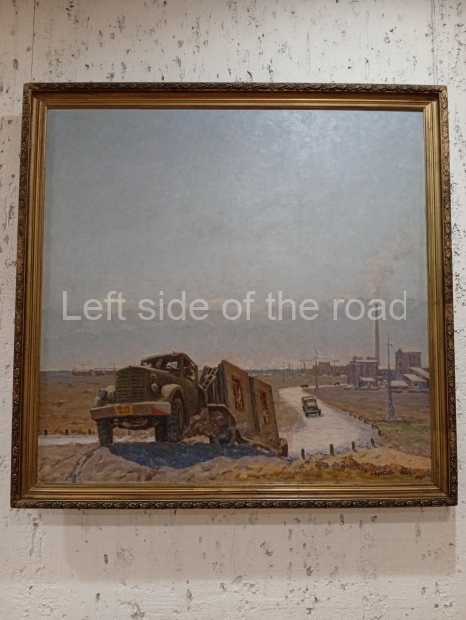

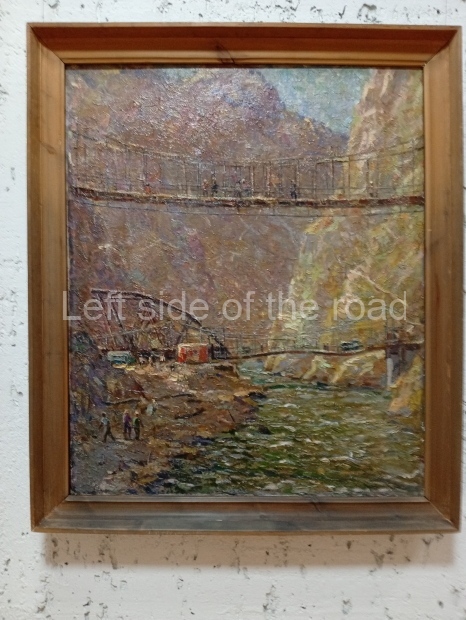

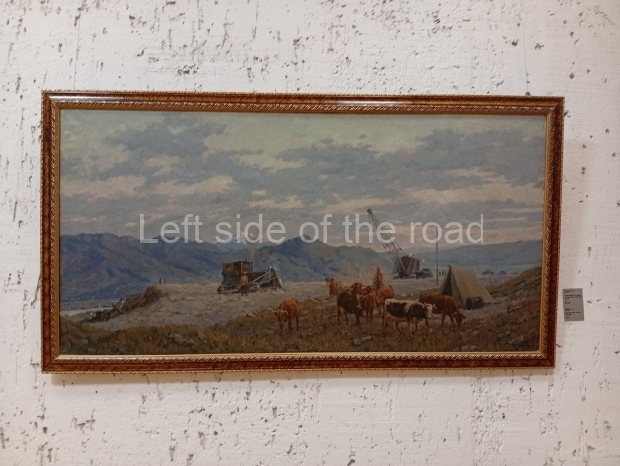

Socialist Realist Art in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan

Introduction

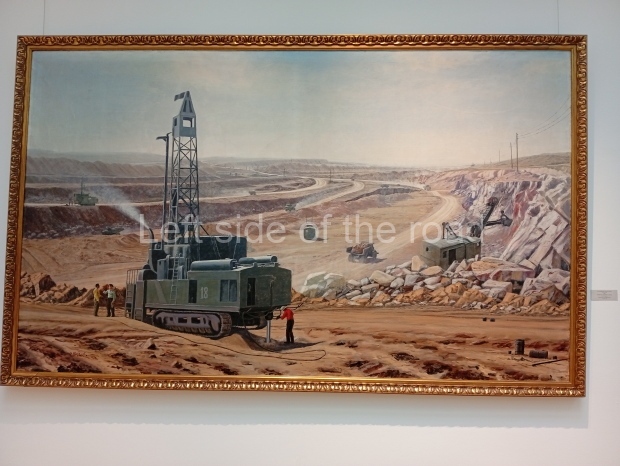

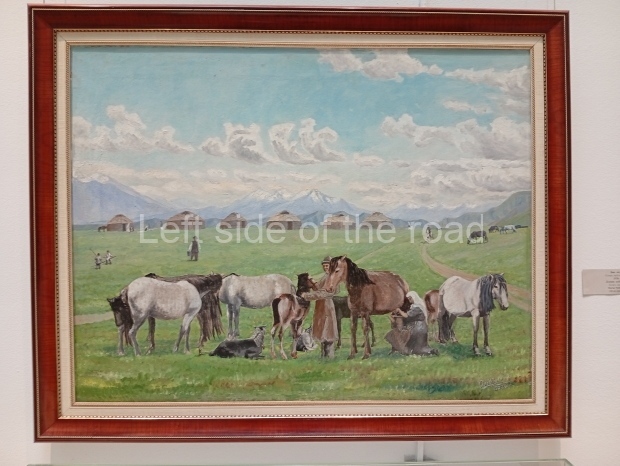

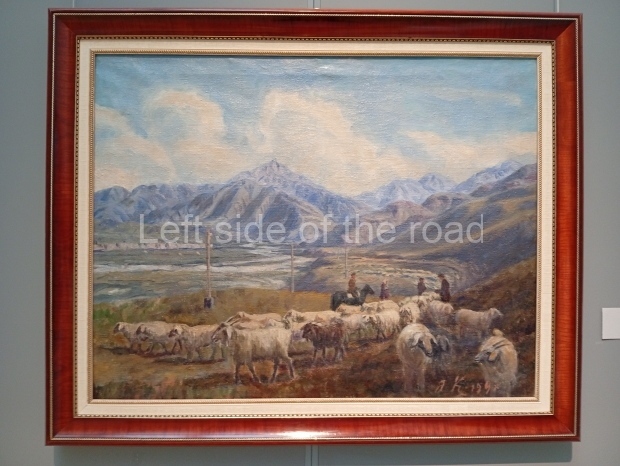

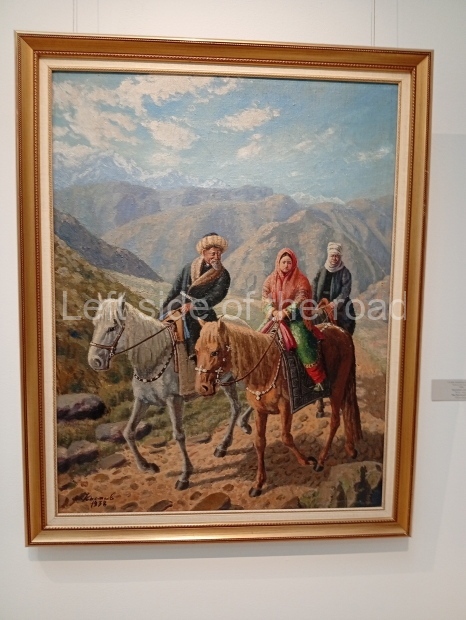

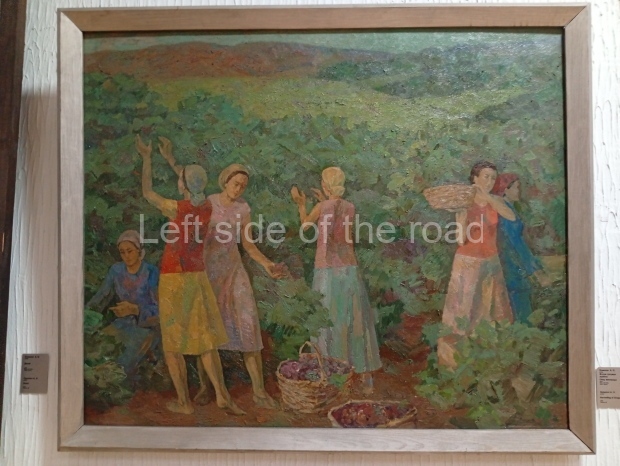

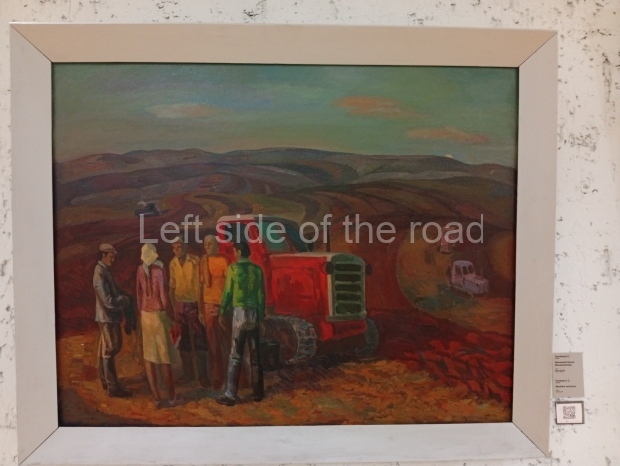

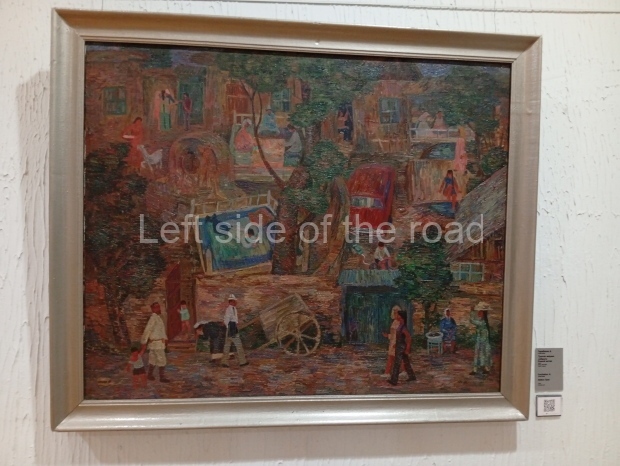

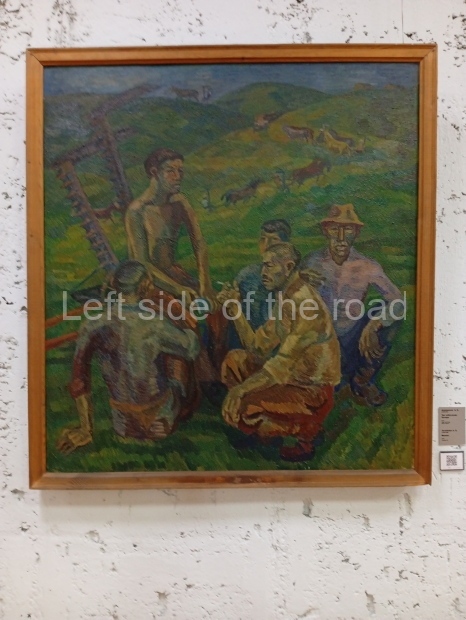

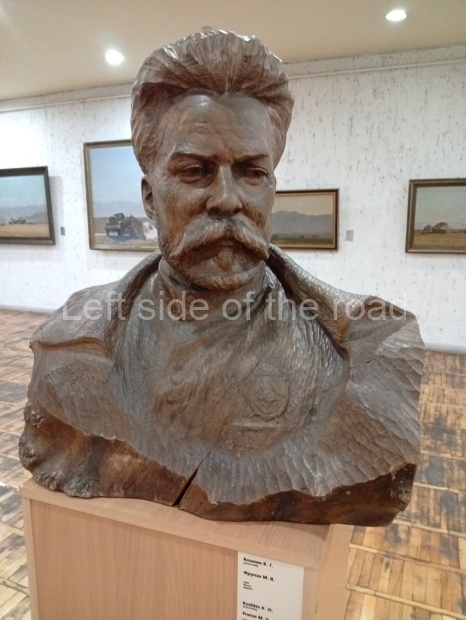

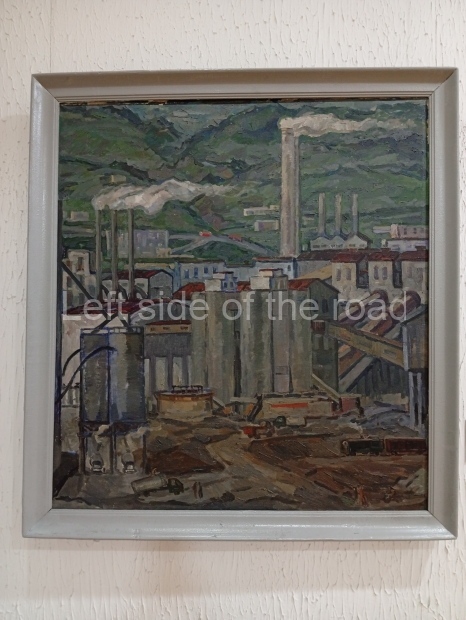

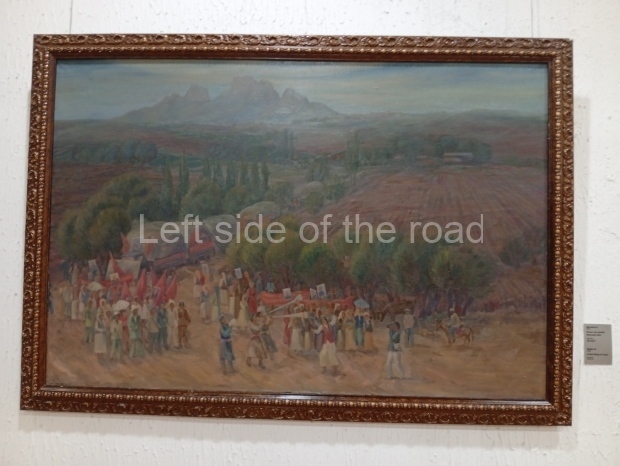

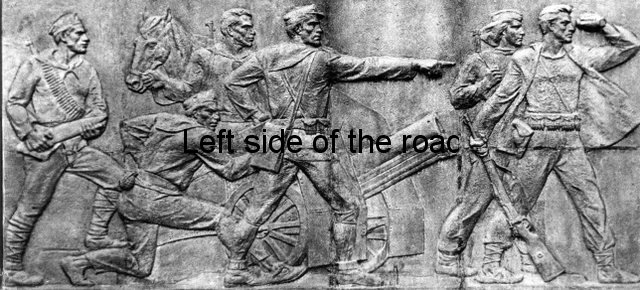

It’s not just the manner in which public statues and monuments are treated that tells you a lot about a particular post-Soviet, post-Socialist society but how they choose to tell the story of the past in their art galleries. Art galleries were constructed in all towns and cities in Socialist societies, showcasing the work of local and national artists. Although all art from the past tells a political story (although then and now such a connection to politics is denied – ‘art for art’s sake’) in Socialist societies the importance of art (in all its forms) in the construction of Socialism was stated explicitly.

In all the countries that started along the road of the construction of Socialism in the 20th century the vast majority of the people would never have had the opportunity to view any of the art works that had been accumulated by the aristocracy and the wealthy – even in those ‘public’ art galleries that did exist. Even though the Hermitage Museum was open to the ‘public’ in 1852 few workers from the steel mills, sailors from the Imperial Fleet or any peasant who had reason to be in Saint Petersburg pre-1917 would have walked along such ‘hallowed’ corridors.

But as statues and monuments from the early 1990s started to disappear from the streets of those once Socialist countries so did paintings and sculptures (gradually in some places more rapidly in others) from the art galleries. Sometimes cloaked as a normal reorganisation of the collection what happened was that paintings which made an overt reference to leaders from the Socialist past or sculptures of those leaders were removed to be replaced with … what? The problem was that if the curators didn’t want to have bare walls they had to have some of those images from the Socialist period – or the galleries would just have to shut down.

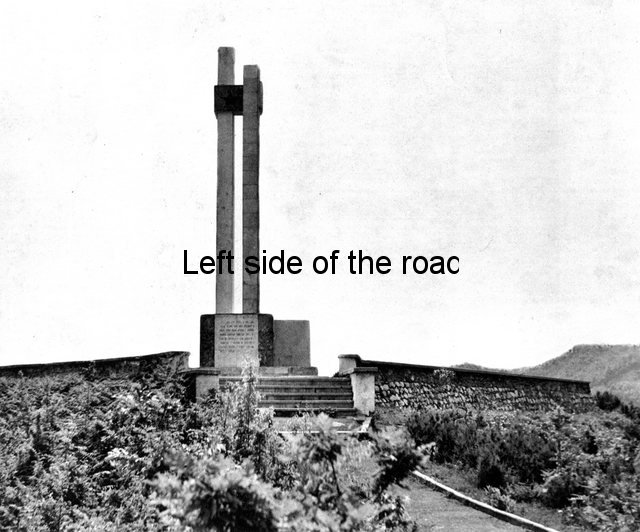

It was ‘easier’ to replace public statues with something new but it also became problematic. Lenin and Stalin were deposed in Tirana to be replaced by the fascist, collaborator and self-proclaimed monarch, Zog – as well as some other ‘monuments’ . In Moscow the statues of Soviet leaders were placed in a museum park across the river from what must be one of the greatest monstrosities to be placed in the open air, that is the huge mess which is the monument to Peter the ‘Great’. In Tbilisi VI Lenin was replaced by a character from mythology, Saint George slaying a dragon. In Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan gaudy statues of feudal lords now ‘adorn’ squares and public spaces once occupied by Soviet leaders.

What all these replacements have in common is a separation from the working class. They bear no relationship to their daily struggles and these images only reaffirm their subservience to the capitalist ruling order.

When it comes to art galleries it’s not too easy to fill the empty places and many locations in post-Socialist societies still display (often the less ‘controversial’) examples from the period on their walls.

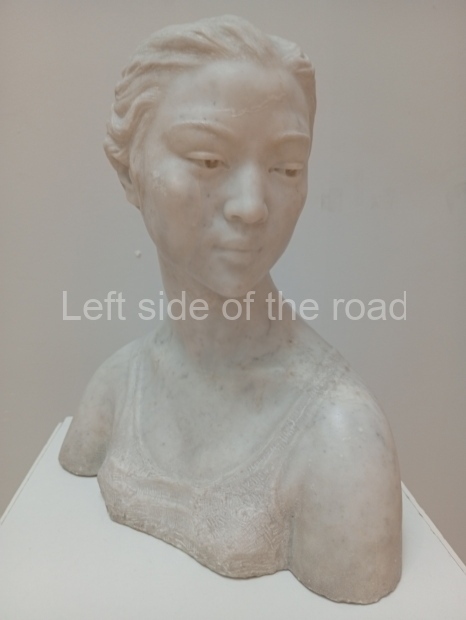

Below are details about the galleries and examples of the art on show at three art galleries in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

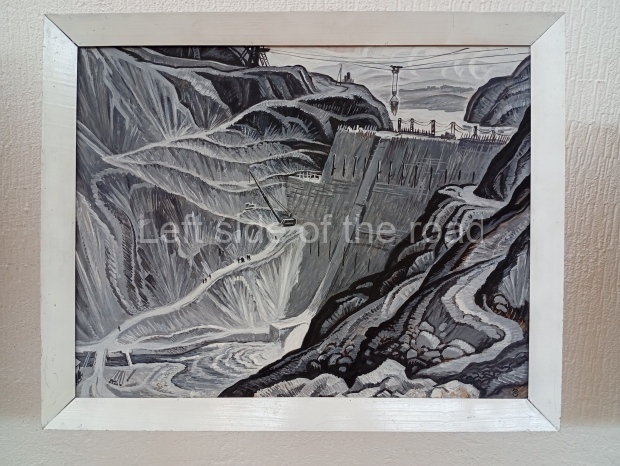

Regional Art Museum – Atyrau – Kazakhstan

This is a small art gallery, of just two storeys, with the collection of Soviet era paintings and sculptures on the first floor. It doesn’t seem to get many visitors and was very quiet on my visit. For those interested in other aspects of Kazakh culture the Regional Museum is just across the road.

Amongst the collection are still some overtly political paintings and prints. However, I am unable to include these in the slide show as I was prevented from taking pictures half way through my visit. I had only been in the country a short time and wasn’t aware that trying to take pictures with anything other than a mobile phone will get you jumped on.

Location;

11 Azattyk Avenue, which is a side street off the main road close to the Central Bridge over the ural River, on the ‘Asian’ side.

GPS;

47.10632 N

51.92281 E

Opening Hours;

Monday – Friday; 09.00 – 19.00

Saturday and Sunday; 10.00 – 19.00

Closed between 13.00 and 14.00

Entrance;

1000 Tenge (£1.40)

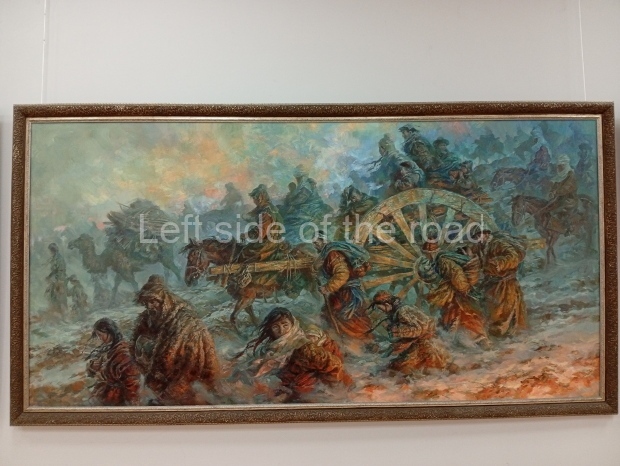

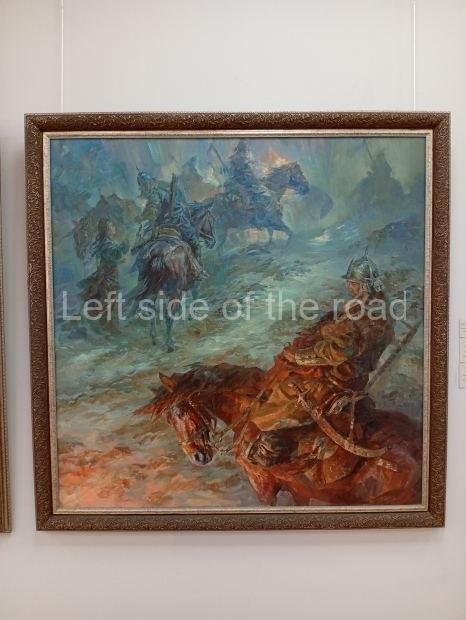

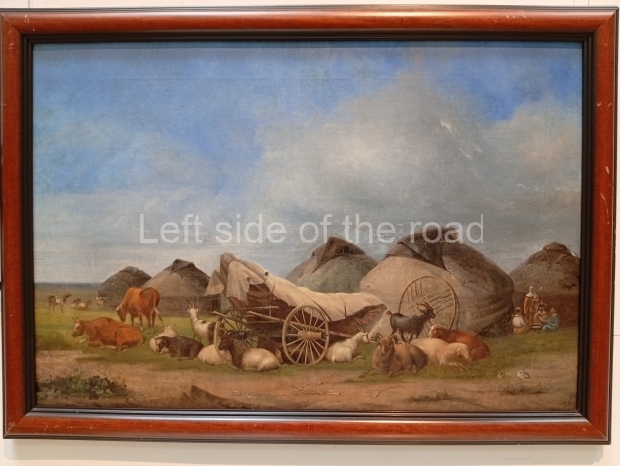

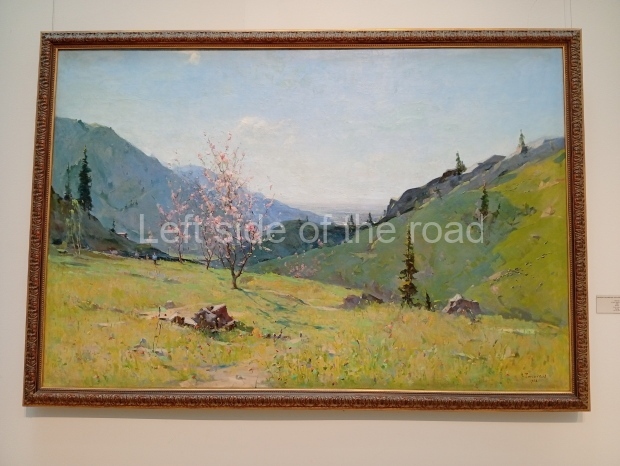

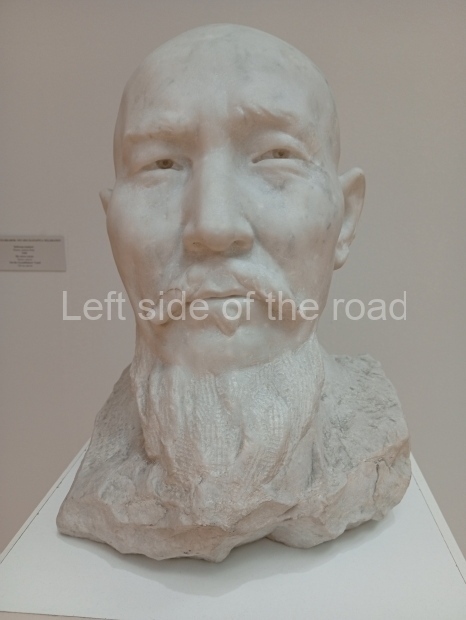

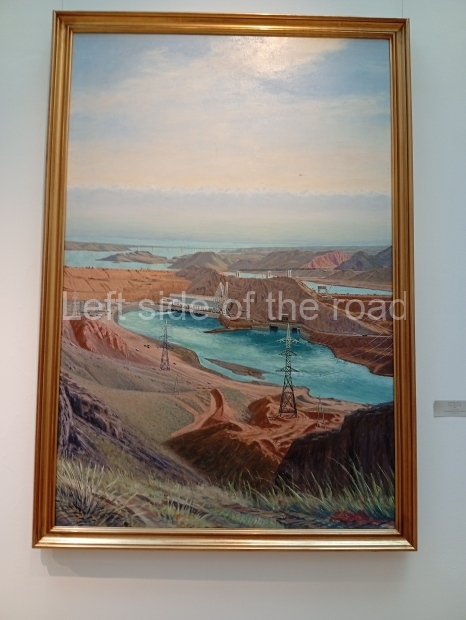

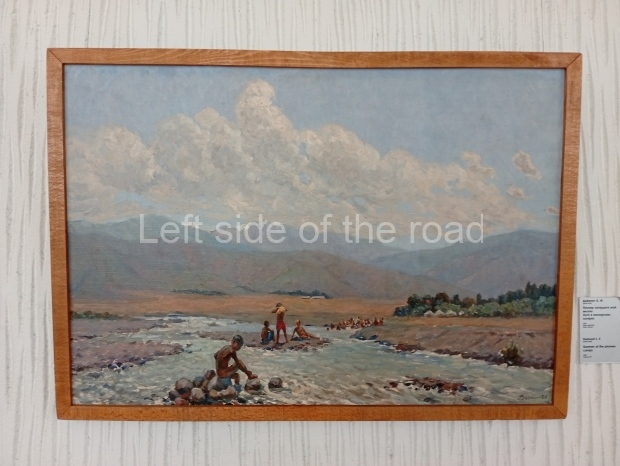

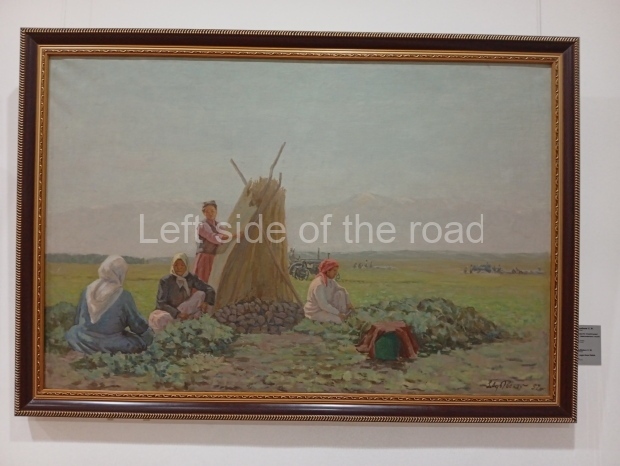

Kasteyev State Arts Museum – Almaty – Kazakhstan

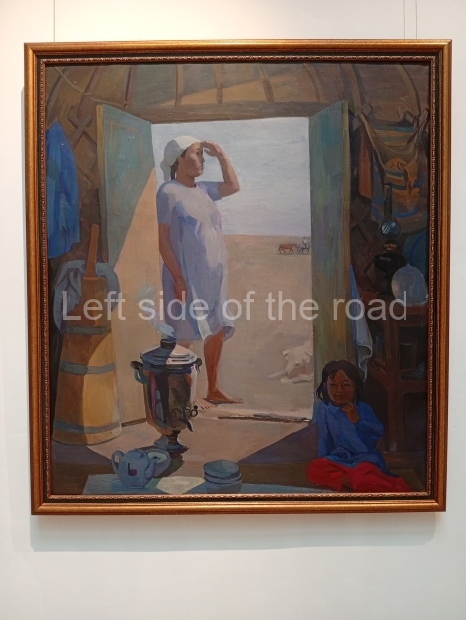

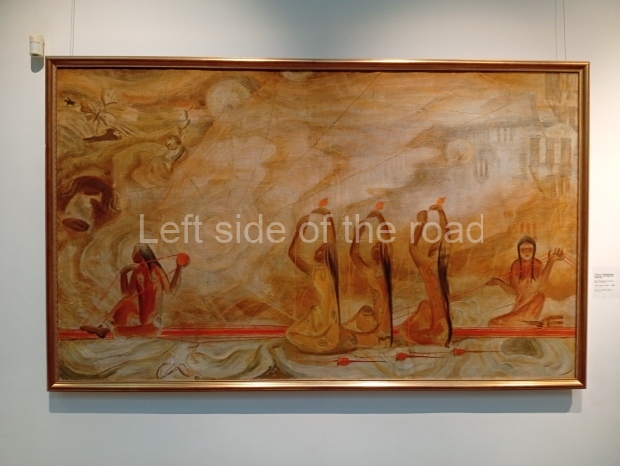

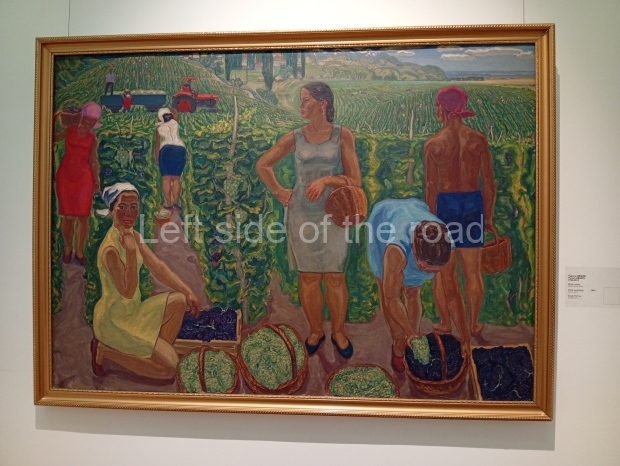

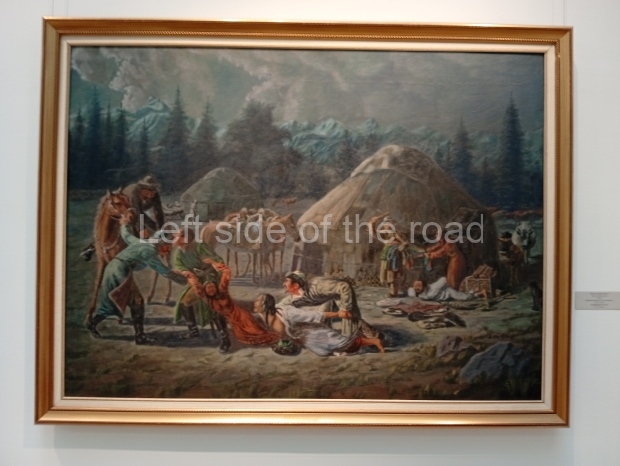

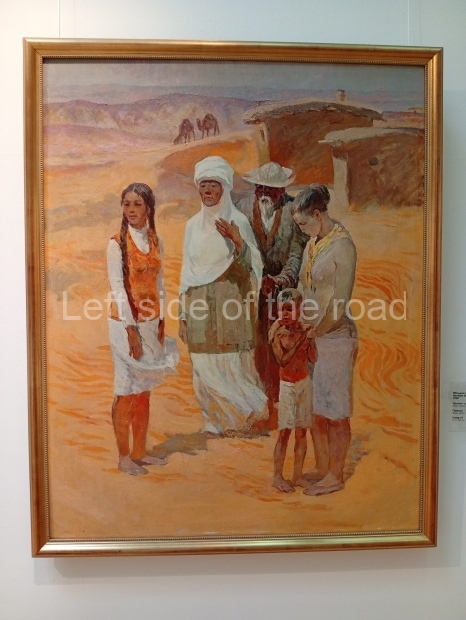

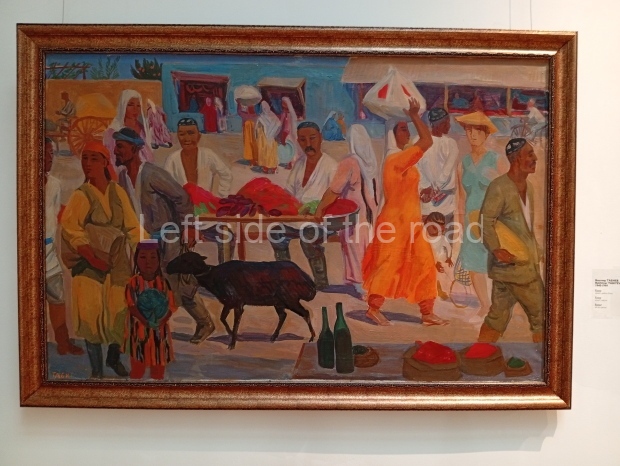

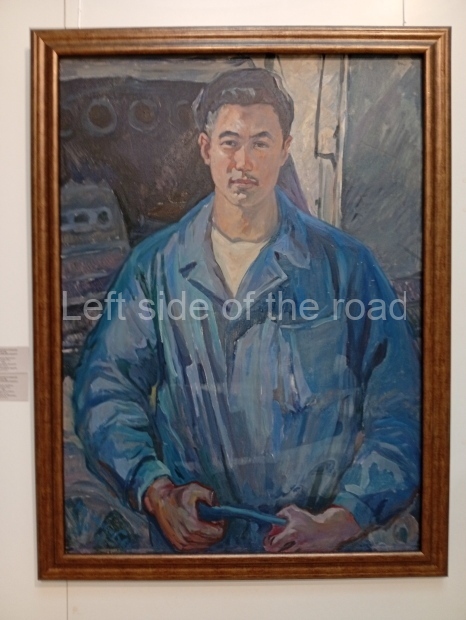

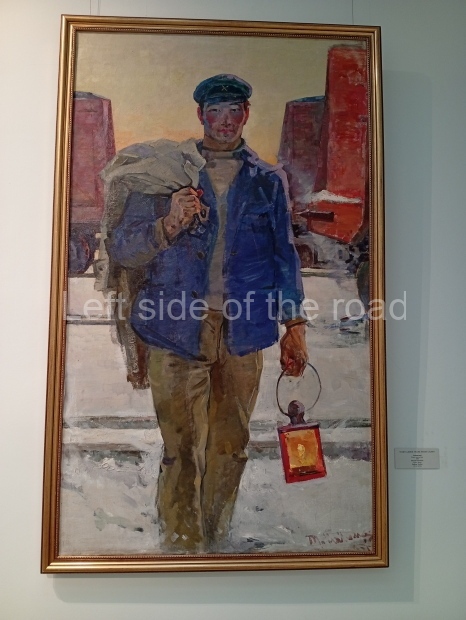

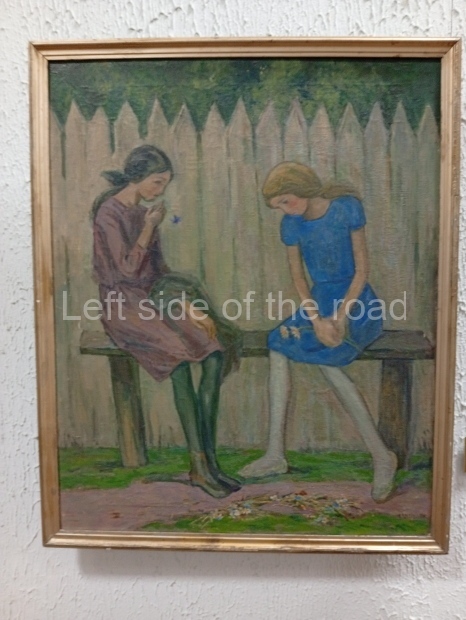

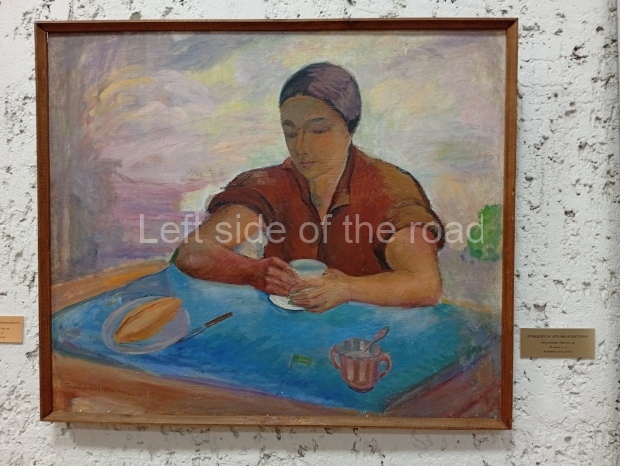

This is a large art gallery in the city that used to be the country’s capital before that ‘honour’ being claimed by the monstrosity which is Astana. The collection covers many aspects of Kazakh art other than paintings and sculptures from the Socialist era with displays of what are normally classified as folk art. However, the slide show only includes work produced pre-1990. Of particular note, and somewhat unusual in such collections of Socialist Realist art, is the two paintings that depict a) the ‘tradition’ of bride kidnapping, which was fought against under Socialism but which has seemingly managed to be revived in the last 35 years and is still a scourge of Kazakh society, especially in the rural areas and b) the sad image of a young woman who is the victim of an arranged marriage.

Location;

Koktem-3 microdistrict, 22/1

GPS;

43.23603 N

76.91931 E

Opening times;

Tuesday – Sunday; 10.00 – 18.00

Closed Monday

Entrance;

500 Tenge (£0.70)

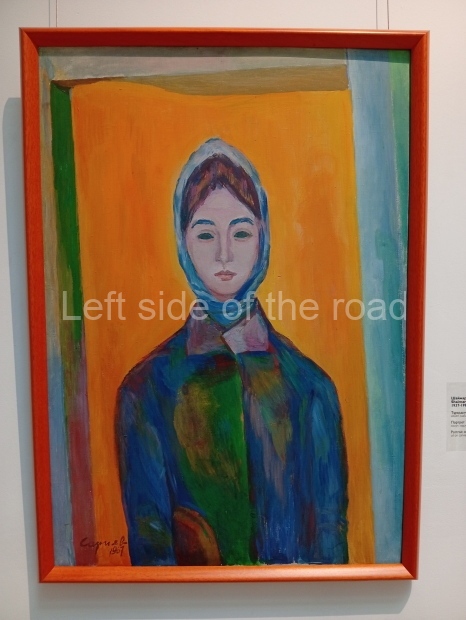

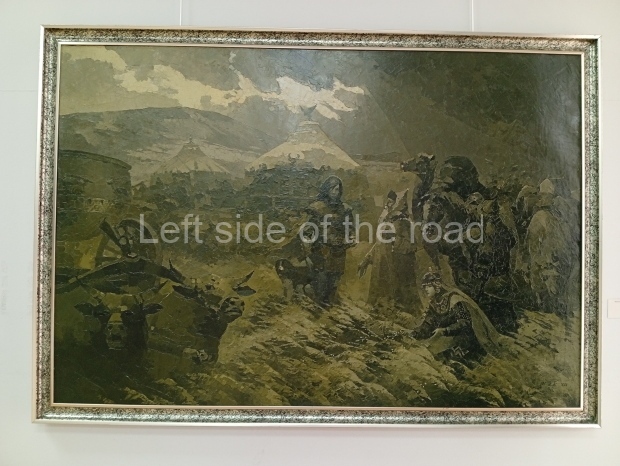

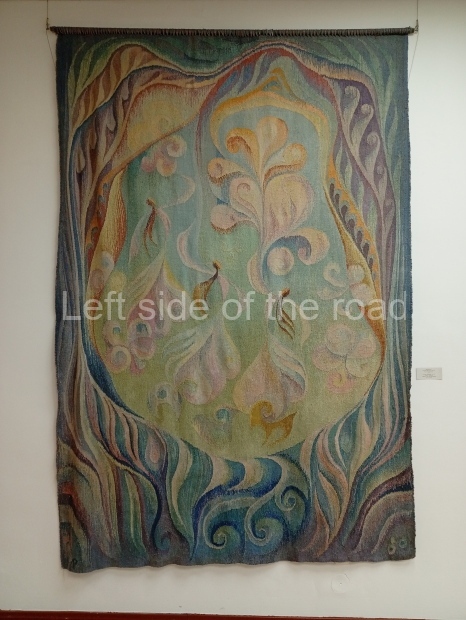

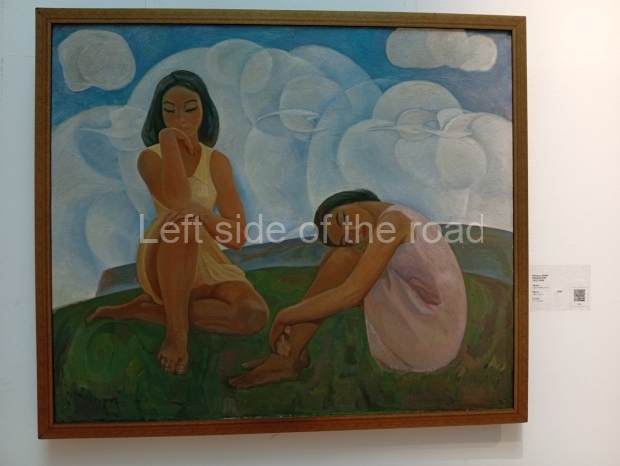

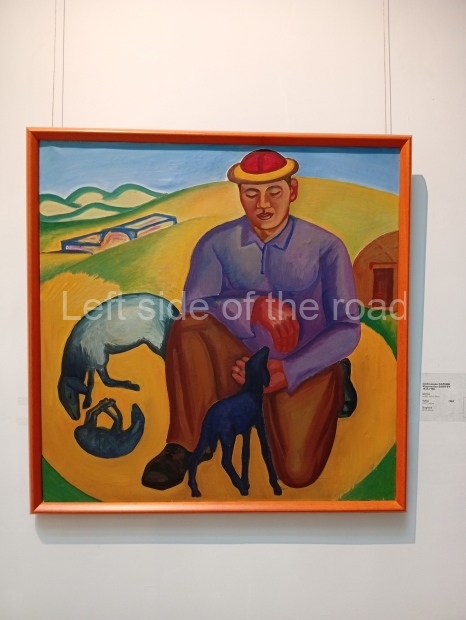

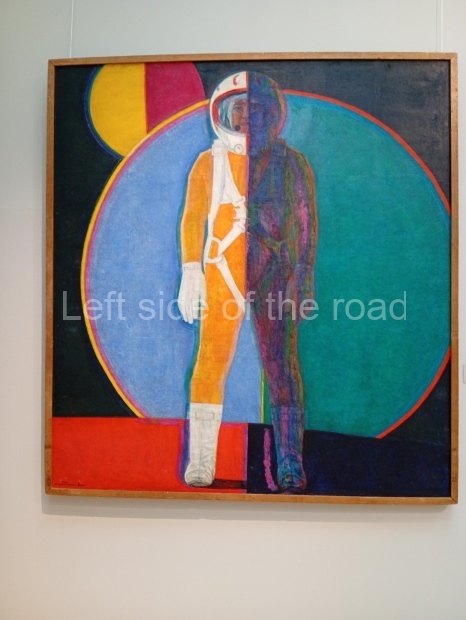

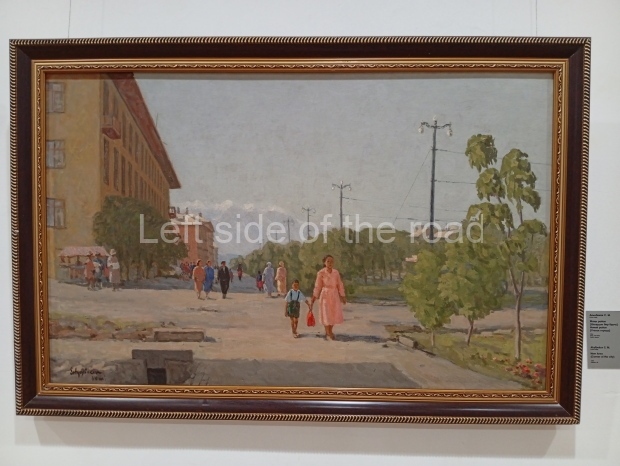

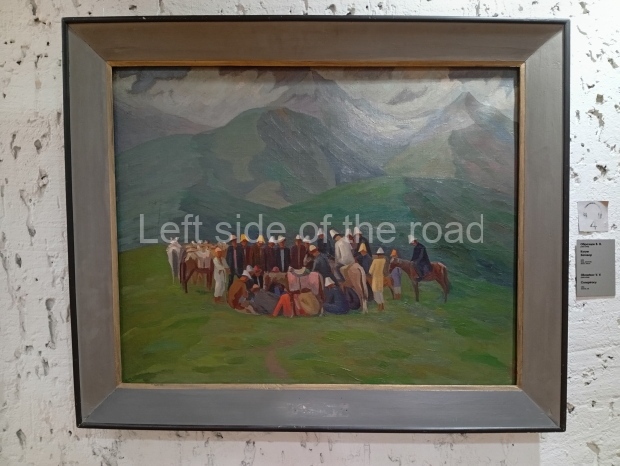

Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts – Bishkek – Kyrgyzstan

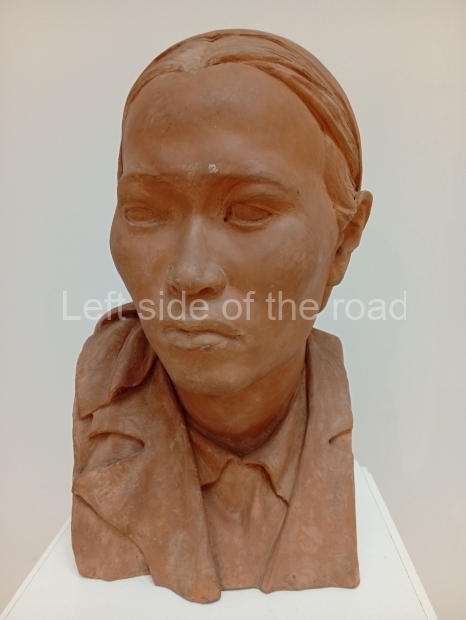

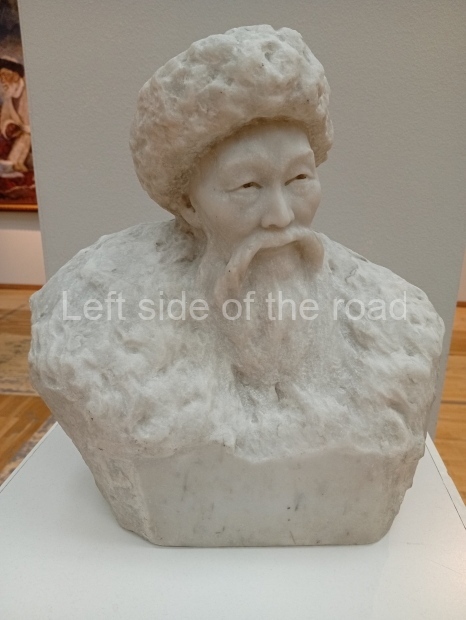

This is another art gallery that displays much more than the art from the Socialist period. One picture to look out for (and which will be recognised by any readers who have an interest in Soviet Socialist Realist Art) is ‘The daughter of Soviet Kirghizia’ by SA Chuykov. This is the artist’s reproduction of the original which is in the New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Location;

196 Yusup Abdrakhmanov Street

GPS;

42.87893 N

74.61082 E

Opening times;

Every day (apart from Monday when closed); 11.00 – 18.00

Entrance;

Free