Partisan Memorial – Gjirokastra

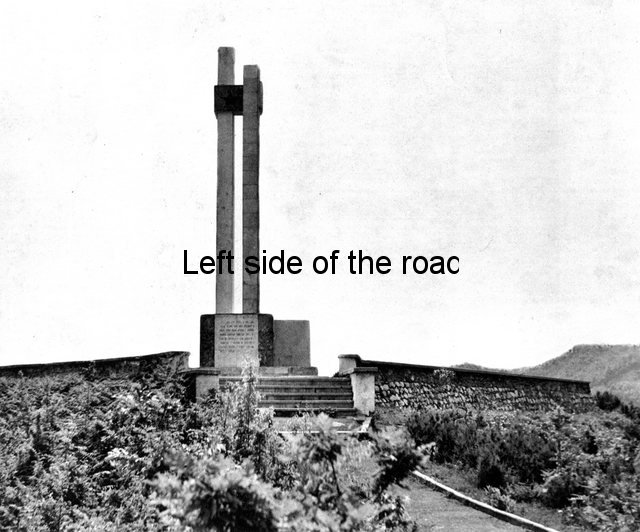

Most of the monuments in Albania are not complex works of sculpture. Many are simple columns, with inscriptions, some of those being quite small. These are known as ‘Lapidars’ in Albania. (‘Lapidar’ doesn’t have a direct translation into English although ‘monolith’ is a possibility – and might even have a German root.) In between the monumental and the columns are stand alone statues and structures and the Partisan Memorial – Gjirokastra, is one of those.

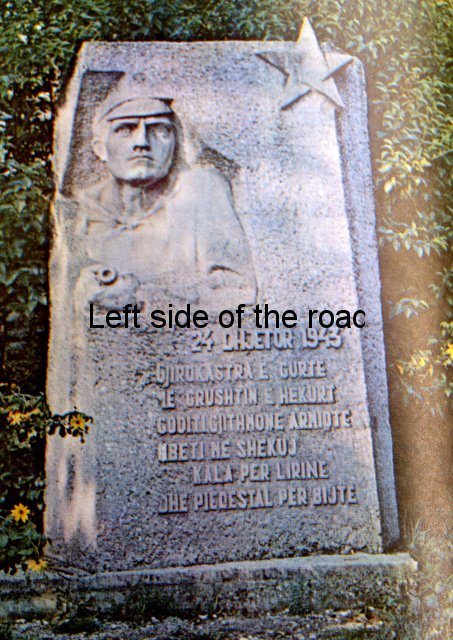

Many of the monuments are either of concrete or bronze but this one is of stone. On close examination, and especially after being cleaned up, the stone is almost certainly limestone. The statue is composed of large blocks to create a shape that looks like the forearm of a human with a clenched fist. Carved into the facade facing the road there is the torso and head of a partisan soldier (male). Because of how it’s constructed I would have assumed it was carved in situ. The sculptor was Stefan Papamihali and it was inaugurated in 1983. Papamihali was also a collaborator, together with Ksenofon Krostaqi and Mumtaz Dhrami, on the education obelisk higher up in the Old Town.

There’s just one individual depicted on this monument. He’s a Communist Partisan, in winter gear, dressed in a heavy overcoat with a thick sweater underneath. On his head is a cap with a star at the front. He’s looking straight out at the viewer. He has both his hands on a light machine gun which is held against his chest.

To his left, and virtually on his shoulder, is the symbol of the double-headed eagle with a star between the two heads. On most monuments that image is usually part of the national flag but here they seem to stand alone.

Above him, at his right shoulder, is the date, in numbers of ’24 12 1943′

This was the date when the town was finally liberated from the German Fascists. The majority of the surrounding countryside in the south of Albania was liberated in the early months of 1944. Commemorating, as it does, such an important event I’m not sure why it’s not in a more prominent location, in the main square for example.

Below the image, carved into the stone, are the words:

‘Qyteti i gurtë mbeti në shekuj kala për liri’.

My translation for this is:

‘The Stone City Castle has been a symbol of freedom for centuries’

‘Stone City’ is one of the nicknames for Gjirokastra from the traditional buildings of the old town which used stones for the roofs as well as the structure of the houses. The ancient Castle dominates the city and this end of the valley and recognisable from miles away.

In general the monument is in a good condition apart from the fact that someone has had a go at his nose and the left nostril has been broken off. (Noses are vulnerable on stone statues, there’s one of Uncle Joe in Moscow that has a chunk missing from the nose.) A number of other monuments in Gjirokastra haven’t fared so well.

I’m not too sure is this is as a result of vandalism or more of an accident. On other monuments the first things to be attacked are the stars, but the two on this statue are undamaged. There’s an element of weathering but that would have been taken into consideration by the sculptor, taking into account the location. It’s facing in a northerly direction and there’s quite a lot of rain in this part of the country in the winter.

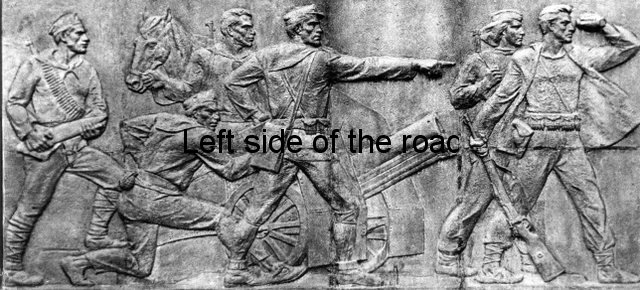

This is a fairly unique style and design for an Albanian commemoration of the Partisans and the victory over the Fascist invaders. In the work of Dhrami and Krisiko, on the different monuments at Peze, for example, you can notice the development of certain motifs.

The simplicity of this statue gives the impression of solidity and determination but, as is always the case in Albanian iconography, the freedom that was fought for can only be maintained by being prepared to use arms. As Mao Tse-tung said: ‘Political power comes from the barrel of a gun’.

One aspect of ALL the statues and monuments to the Partisans in Albania is that the individuals are always confident, heads raised, prepared to take on the enemy and face the difficulties of the struggle. That goes for both the male and female partisans. Compare that with the representation of the partisan in the capitalist countries, for example the Manzu monument to the partisan in Bergamo, Italy.

Since my first visit to Gjirokaster this memorial has been cleaned and looks a lot better as the black weathering has been cleaned off. All the monuments and lapidars in Gjirokaster are in a better shape than they were a few years ago, as can be seen with the bas-relief outside the high school. But this is not the first representation of a Partisan to have existed in Gjirokaster.

I have no details (as of now) about this memorial but assume it was located in the same position as the existing one.

The text reads, in Albanian:

24 Dhejtor 1943

Gjirokastra e gurte me grushtin e hekurt goditi gjithmone armiqte mbeti ne shekuj kala per lirine dhe piedestal per bijte.

This translate as:

24 December 1943

Gjirokaster, with the stony ‘iron fist’ to smash its enemies, has remained, over the centuries, a stronghold of freedom and an example to our children.

(Slightly more poetic than the statement on the present memorial.)

It’s not unusual, in the history of Albanian Socialist Realist sculptures, for there to be changes and modifications to the monuments as the society moved forward. This can be seen in the evolution of the statue in Skhoder of the ‘Five heroes of Vig’ and also in the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Borove. What is strange here is that the ‘new’ statue develops the original idea and seems to be larger in scale. However, the original was itself a fine piece of art and it seems a tragedy that it should have been destroyed (if, indeed, that was the case) just to make way for a newer and larger piece. If it had to make way for the new why not place it in the Castle Museum?

If the reason for its replacement is unsure the timing is understandable. 1983, the date on the present statue, was the 40th anniversary of the Liberation of the city. It seems that in the lead up to that date a number of new monuments appeared in the town, the stone bas-relief of the musicians and dancers and the obelisk to education being two examples of this.

Location:

The statue is at a bend of the road (Rruga Gjin Zenebisi) that heads up to the old town. If coming from the south, from Permet or Saranda, it’s the first road up on the left as you come into the Gjirokastra city limits and the monument is about 300m from the junction. There used to be a bust of Enver Hoxha (picture above) close to that junction but that would have been destroyed in the counter-revolution of 1990. This would have been opposite the most severely vandalised bus stop I think I’ve ever seen which is almost a work of art in its own right.

GPS:

N 40.076256

E 20.14575097

DMS:

40° 4′ 34.5216” N

20° 8′ 44.7035” E

Altitude: 261.4m