El Puente

El Puente – Honduras

Location

This site is situated north of the Florida Valley in the town of La Jigua, in the Copan department of Honduras, near the village of La Laguna, on the road to Copan Ruinas. Its name is derived from a stone bridge that once stood over the River Chamelecon, situated on the estate of the same name. It is one of the southernmost Maya cities in the geographical and cultural area known as Mesoamerica. This distinctly Maya settlement was one of Copan‘s satellite cities and probably functioned as a nexus between the Copan Valley and the remainder of Honduras. The archaeological park is situated in an area of nearly 56,000 sq m and the core area of the site encompassed 2 sq km and 210 structures. It occupies a strategic part of the valley, just 2 km from the confluence of the rivers Chinamito and Chamelecon.

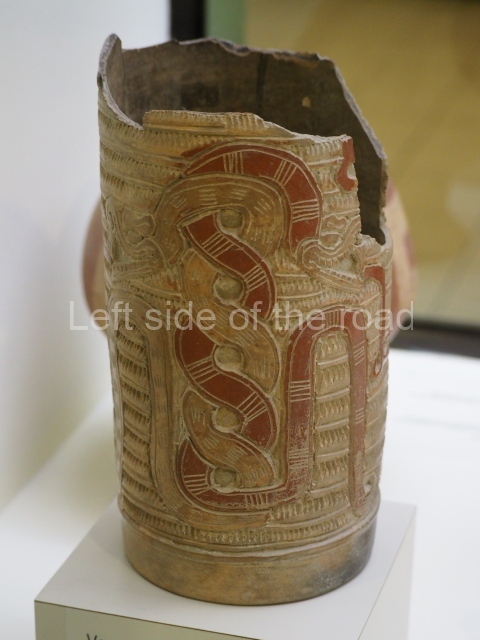

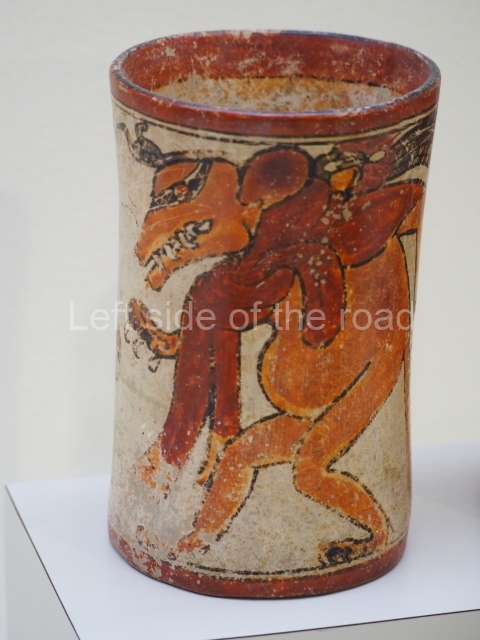

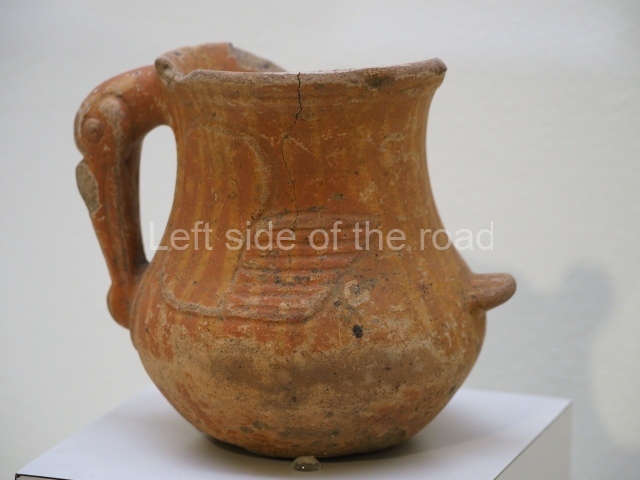

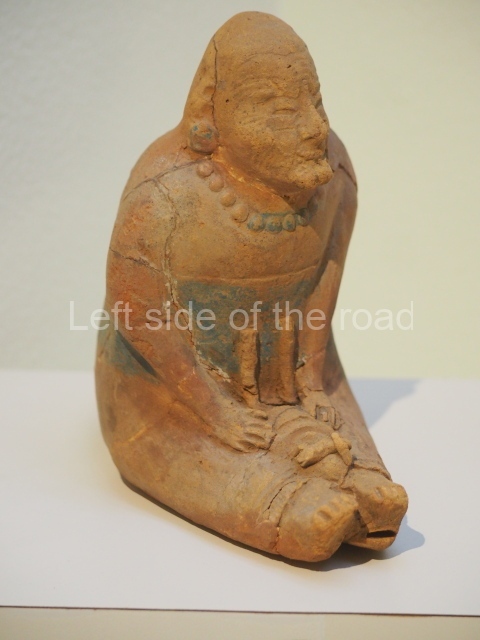

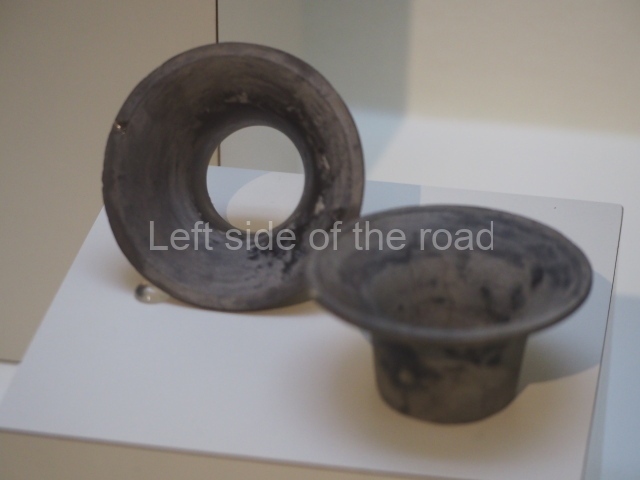

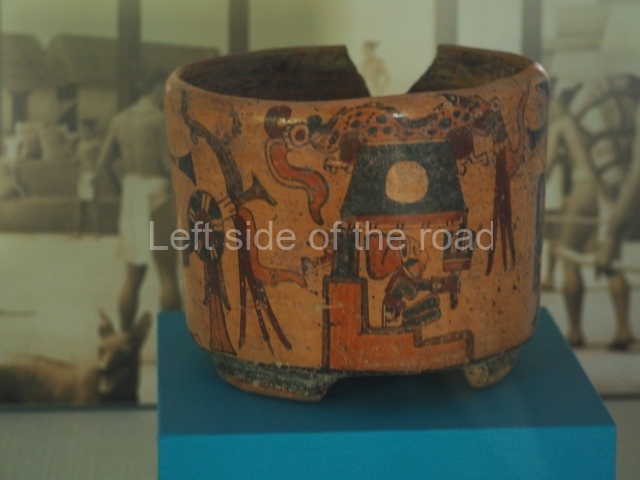

Visitors can follow nature trails and admire the different species of butterflies and birds. However, much of the surrounding vegetation has been chopped down to make way for livestock breeding. Accessibility is good; visitors can take the branch road leading from San Pedro Sula to Copan Ruinas. There are sign posts along the way and the turn-off to the site is indicated in the village of La Entrada. In 1989 the site of El Puente was declared a National Monument. It is the second largest archaeological park in the country and is open every day of the year from 8 am to 4 pm. There is a visitor centre, site museum, bookshop, basic tourist facilities and a scale model of the site. There is also a rest area at the west end of the park, on a meander of the River Chinamito. The archaeological park was developed by the Honduran government in association with the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) as part of a conservation programme encompassing the archaeological sites in the Venta and Florida valleys. The site museum holds examples of ceramics, sculptures and other objects of interest related to the site and environs. To strengthen the ties between the two nations, it also has a special section devoted to Japanese culture and how it compares to the Maya culture.

History of the explorations

The first reports were provided in 1935 by the Danish explorer Jens Yde, although this may well be the site reported by Samuel Lothrop in 1917 under the name of El Chinamite. Yde left a detailed description of the buildings and the first map of the archaeological site. Various mounds, and Structure 1 in particular, were looted on several occasions during the 20th century, and no one visited the site again until the 1970s, coinciding with the inspections conducted by the La Entrada Archaeological Project (PALE). In 1984 a group of Japanese archaeologists and experts from the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History conducted surface reconnaissance in the valleys and dug prospecting wells. A new map of the ruins was also drawn up. Under the auspices of the governments of Honduras and Japan, the explorations yielded over 680 archaeological sites in the region. Meanwhile, the first systematic excavations and the consolidation of the main buildings were being carried out. Nowadays, visitors can admire the restored core area and the various construction phases of some of the buildings. In recent years the natural surroundings have been protected and a large part of the Honduran rainforest has been recovered.

Site description

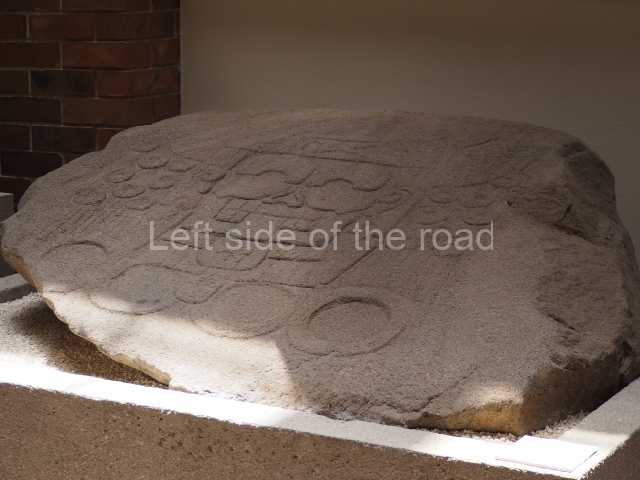

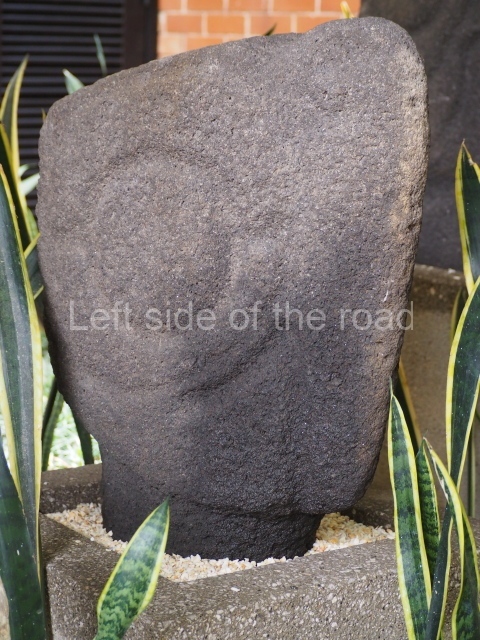

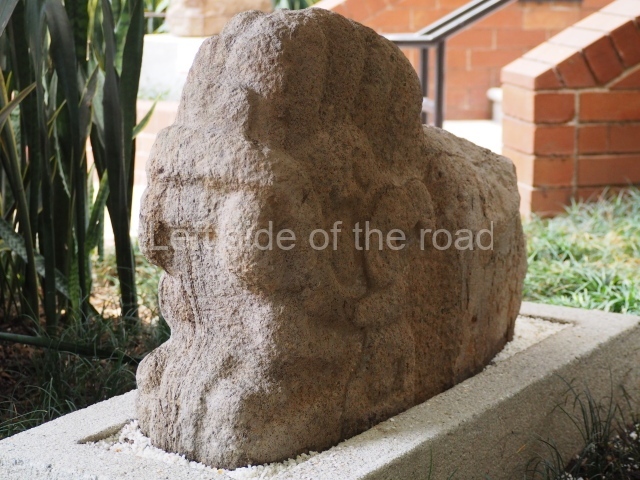

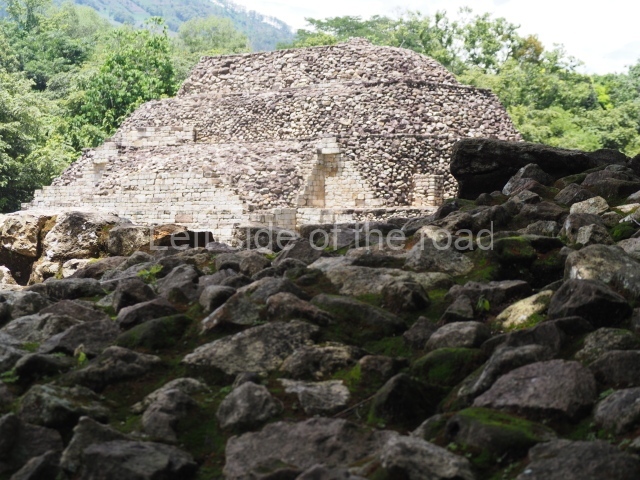

The main group consists of six plazas arranged along an east-west axis and on the banks of the River Chinamito. The civic-ceremonial precinct is composed of a large rectangle delimited by elongated, interconnecting structures comprising public and private areas with various construction phases. The settlement pattern immediately recalls Quirigua in Guatemala, with which it shared, along with Copan, certain architectural characteristics. Situated around the core area are various residential groups, including Group P which has two plazas and approximately 20 mounds. The same valley in which El Puente is situated also contains the sites of Las Tapias, El Abra, Los Higos, Las Pilas, Nueva Suyapa and Techln, which share similar cultural characteristics and may prove to be of great archaeological significance. Access to the main group is via a 500-m path which commences at the scale model in the museum and crosses a few fields with several mounds visible on the horizon. The tour of the site begins at the east end and structure 3 i, which has six construction phases and stands 5 m high. Situated in front of the building are an altar and stela, among the most distinctive features of the site. Continuing through the plaza is Structure 26, an elongated building with steps and at least two construction phases. This structure is oriented north-south, delimiting plazas B and C. It may have been a variant of the Group-E structure, the astronomical marker of the equinoxes and solstices to be found at other sites in the Maya area. Associated with structure 26 are an altar and a monolith, completing the group. Continuing through Plaza B visitors reach Structure 1, which stands 11m high and is the largest construction at El Puente. The explorations confirmed six construction phases. All four sides were restored but looting has prevented conservation of the top of the structure.

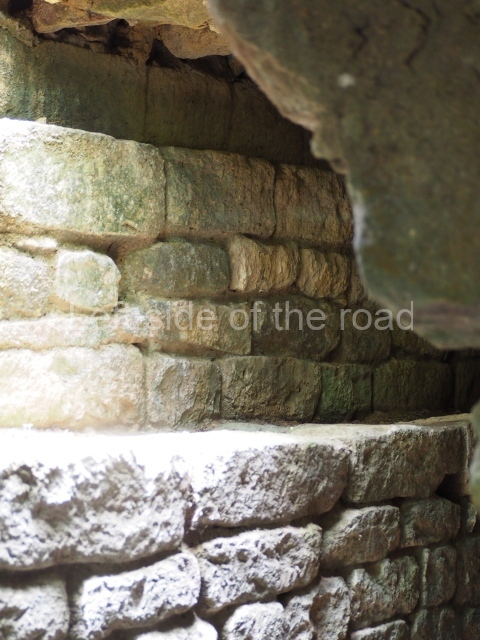

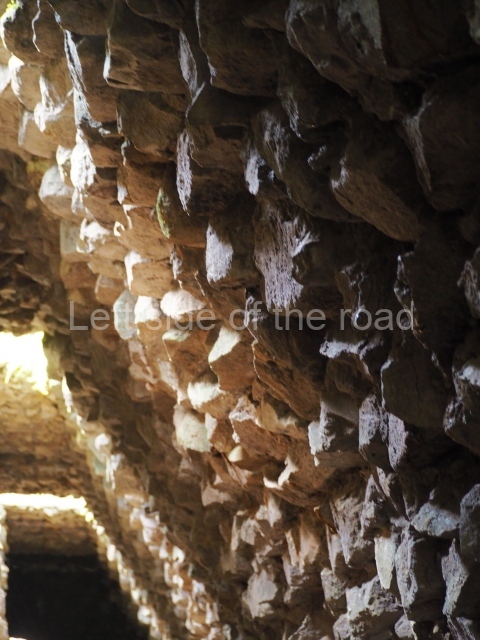

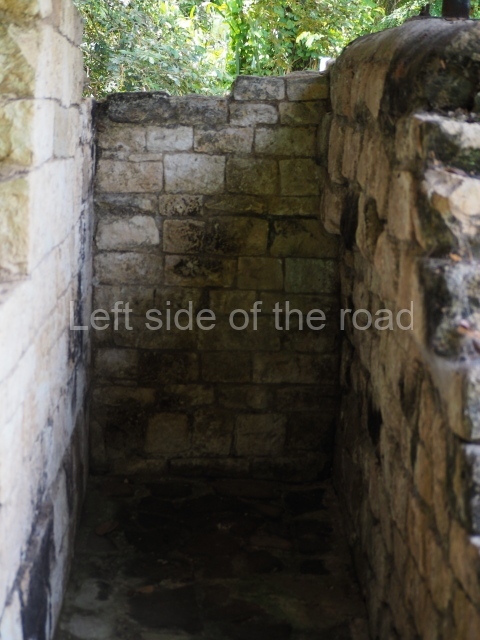

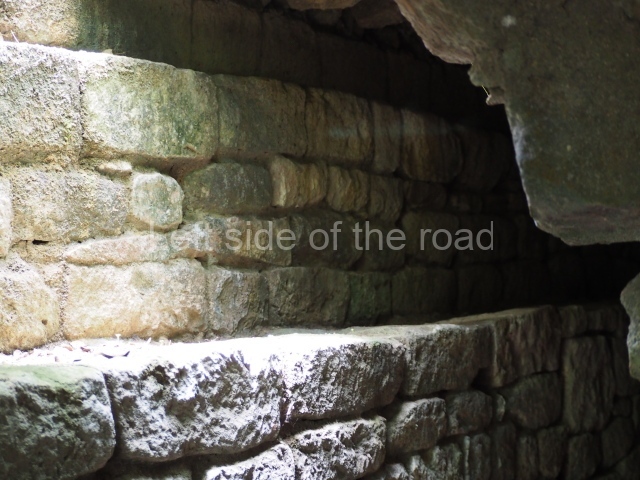

Situated in plaza a is structure 10, which seals the south side of this section and forms part of the ceremonial precinct. The excavations conducted to uncover this structure revealed four construction phases and abundant archaeological material. Visitors can enter the structure and see these earlier phases. The tunnels, which are accessed from the top of the structure, provide a fascinating insight into the construction systems used by the ancient Maya. In Mesoamerica, burying earlier buildings is a common practice and the renovation of constructions was certainly linked to the stars or to the end of cosmogonic cycles. Situated north of the plaza is Structure 3, which also displays several construction phases and an exquisitely carved facade. At the top of the structure, a narrow door leads to the earlier constructions, offering visitors a genuine journey in time.

At the north-east corner of Plaza A are structures 4 and 5. These form an interesting group and must have been residences for the elite who had exclusive access to the ceremonial precinct and who possibly controlled the place. This unit was equipped with every facility: aqueducts, drainage channels and benches for resting on. In the central part of the group are various elegant rooms which are connected by a common platform at the front. The stucco finish of the benches and floors inside the rooms are in excellent condition. The same building method and materials, principally tuff, were used in every building. The walls and floors were clad with stucco. Some of these claddings, principally those on the exterior facades, were painted red. Stone channels were embedded into the roofs to evacuate rainwater. These architectural features, accompanied by explanatory diagrams, are on display in the site museum.

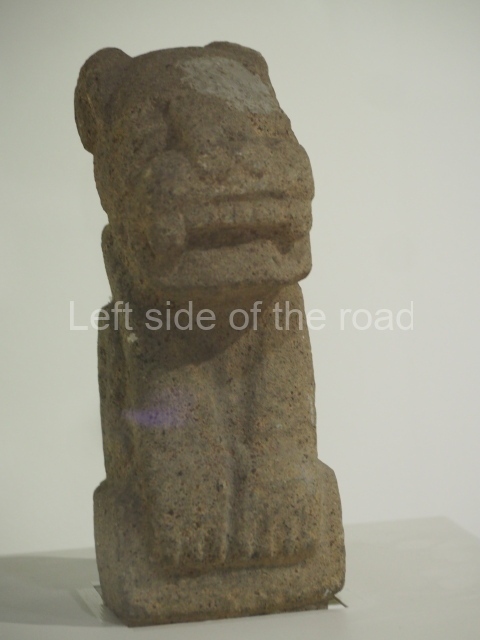

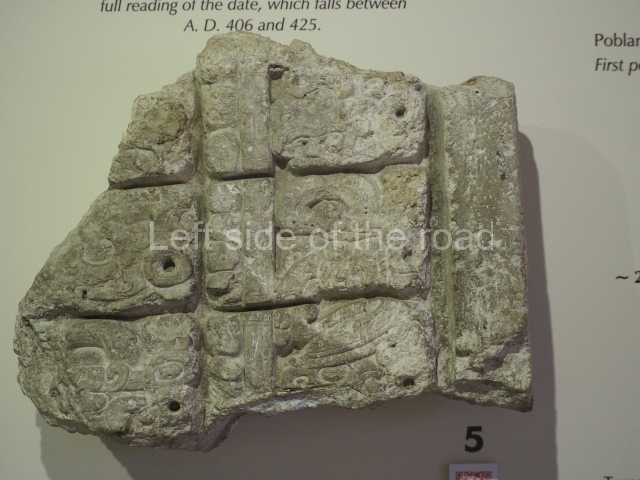

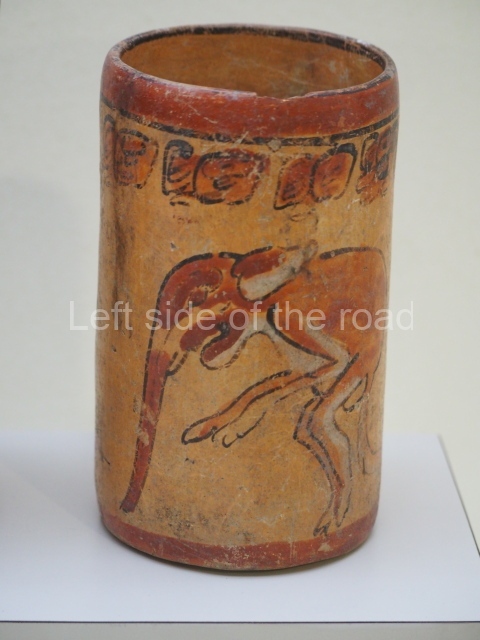

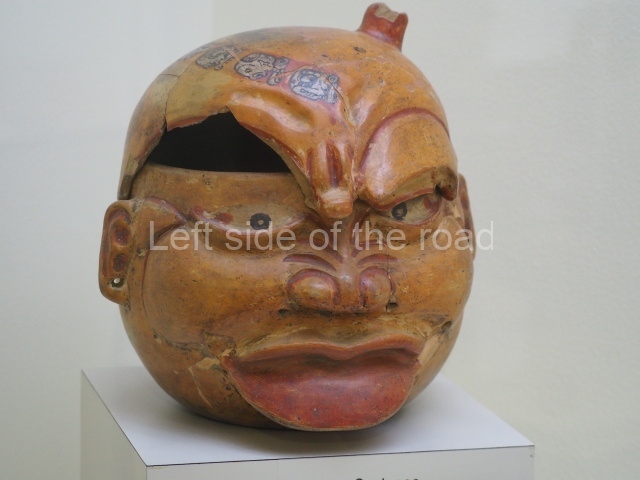

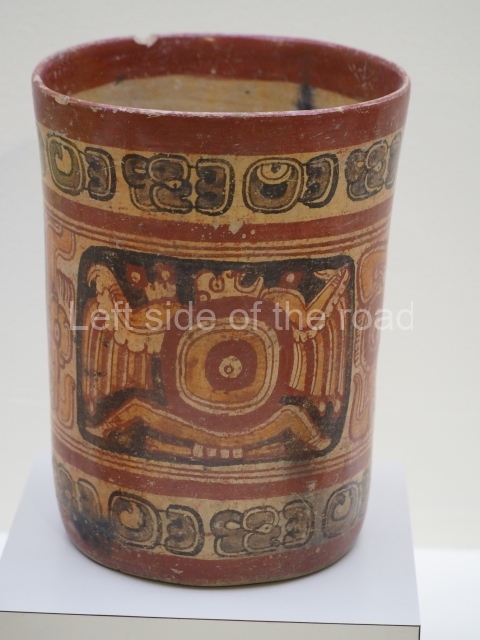

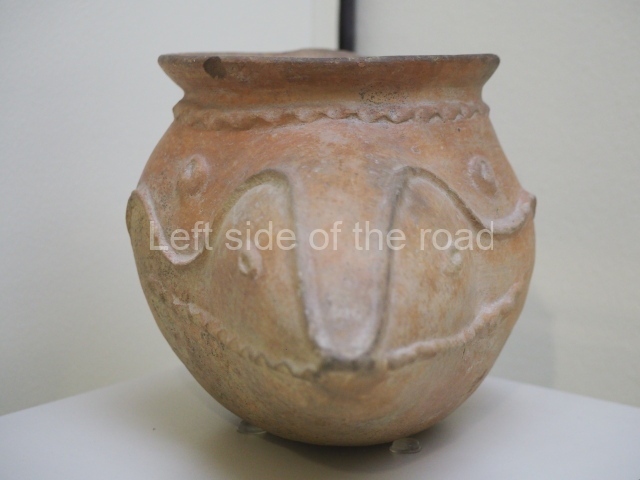

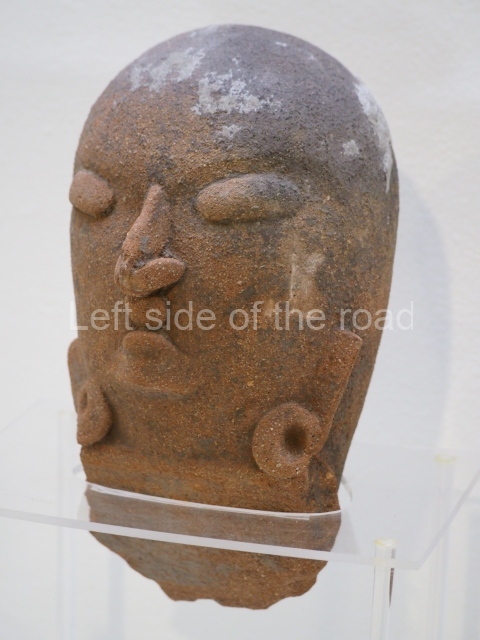

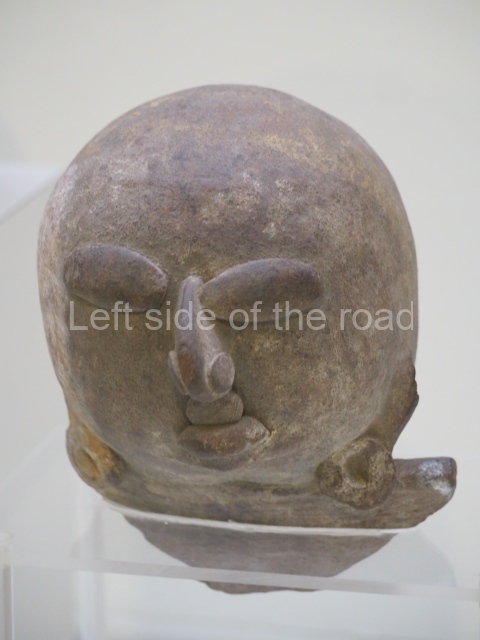

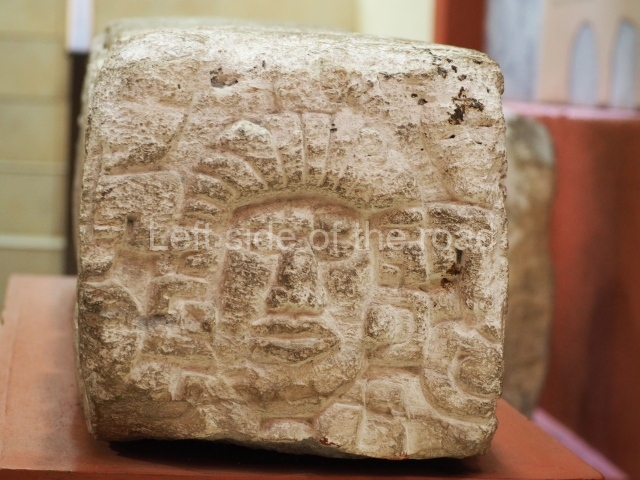

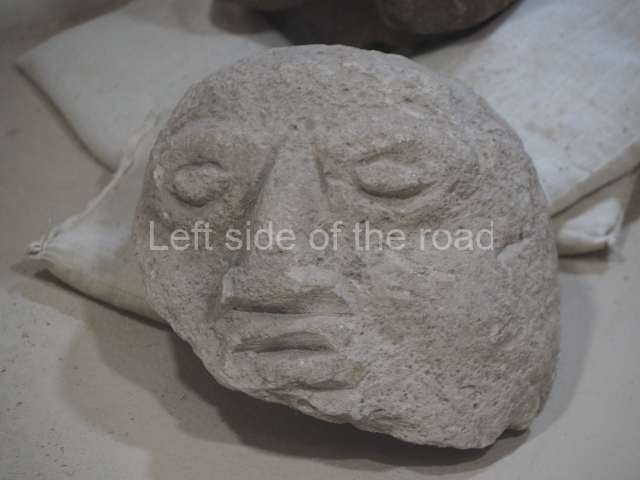

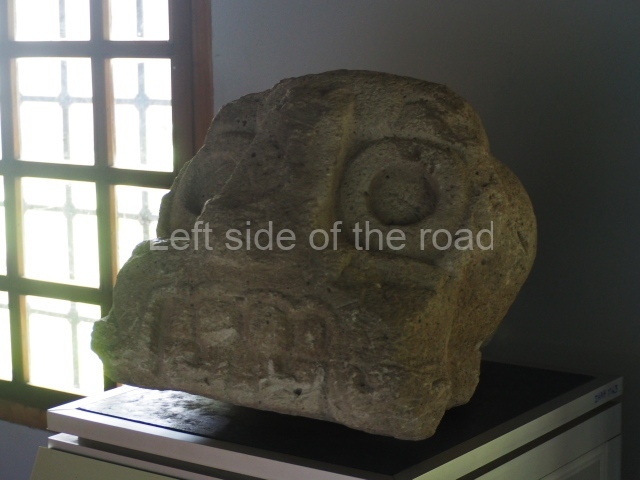

The excavations yielded abundant archaeological material, especially burial ceramics and offerings. Other recurring elements are conches, lithic material such as jade, grinding stones, flint, obsidian and other instruments, as well as bone and other items for domestic use. Twenty-one burials have been uncovered. Interestingly, the lid of one of the incense burners found at El Puente (on display in the museum) bears a certain similarity to those found in the Hieroglyphic Stairway Temple at Copan, which confirms close ties between the two cities. The other important pieces in the museum include the Stela of Los Higos, reported by the famous Mayanist Sylvanus G. Morley, and the alabaster vase of El Abra, which bears the name of Ruler 16 at Copan, Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, around AD 775.

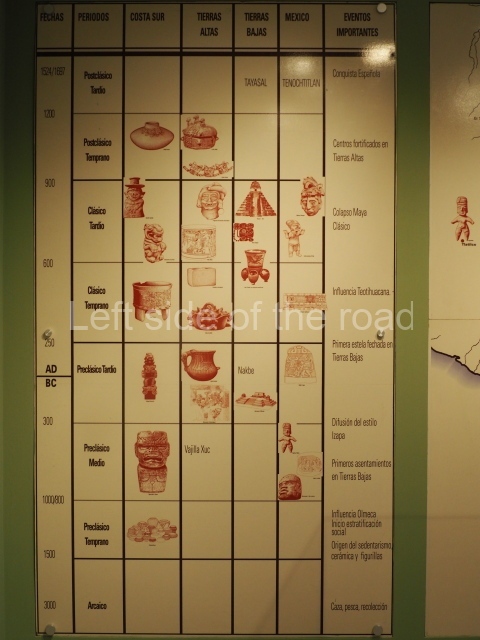

El Puente emerged around AD 600, although some of the ceramics date from an earlier period. In the Late Classic (AD 600-800) it was the most important site in the Florida Valley, and most of its importance and building activity date from this period. Like other Maya settlements, during the Terminal Classic (c. AD 850- 950) it was practically abandoned. The studies on its population genetics and the radiocarbon dates established confirm strong ties between Copan and El Puente. This site appears to have been a satellite city of Copan whose mission was to control the entire region. Some of the unknown quantities about the site are the subject of ongoing research.

Mauricio Ruiz Velasco

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp560-563

How to get there:

From Copan Ruinas. Aim for the buses that go to La Entrada. They leave from the other side of the bridge to the town of Copan Ruinas, on the way to the main Copan archaeological site. Try and leave on the bigger of the minibuses. They all cram as many people inside as possible but the bigger bus is a little more civilised. Journey takes around about 2 hours, depending on how long they might stop to get extra passengers. You want to get off at the road junction at La Laguna, just a few kilometres before arriving in La Entrada. Bus fare L80.

At the junction there are always mototaxis. Take one of these. The site is about 4 kilometres away, about an hour’s walk, with a few steep climbs. The mototaxi will cost L20. You could also try to flag down a ‘pick-up’. On your return flag down the first mototaxi or pick-up back to the junction. Then do the same for any Copan Ruinas bound minibus.

GPS:

15d 06’36” N

88d 47’30” W

Entrance:

L55