Tikal

Tikal – Guatemala

Location

The site is situated 68 km by road from Flores and the airport in the Department of Peten in Guatemala; it is 98 km from Melchor de Mencos, a Guatemalan town on the Belizean border. To protect the ruins in this fascinating city, in 1955 the Tikal National Park was created, the first and largest (576 sq km) in the whole of Central America. Nowadays, the site forms part of the core area of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. The Guatemalan government granted National Monument status to the site, which was ratified by UNESCO when it became a World Heritage Site in 1979 and a Universal Monument in 1986. Inside the park there are three hotels and restaurants serving national and international food. It is also possible to purchase handicrafts. Tikal has a visitor centre offering information on special birdwatching tours as well as guides for accompanying visitors who wish to explore the rainforest trails at the site. Access to Tikal is via an asphalt road from Flores. If you are coming from the Belizean border, you will automatically join this road and then just follow the road signs. The road that will connect Tenosique, in Tabasco, and Tikal is nearly finished.

History of the explorations

Tikal is an outstanding site not only because of its monumental architecture but also its long dynastic history. Archaeological research commenced with the recording of the sculpted monuments and the description of the buildings by Modesto Mendez in 1848, who published his findings in the Gaceta de Guatemala, but it was not until 1881 that the first topographical map of the site was drawn up, by Alfred Mudslay, showing the five main temples and the core area. In 1895 Teobert Maler produced a more accurate map of the central area and altered the nomenclature of the buildings, and in 1911 Alfred Tozzer drew up another map. All of these people also took extensive photographs of the site.

The first scientific interventions commenced in 1956 with the research conducted by the University of Pennsylvania, and continued until 1970. The first field director, Edwin Shook, led the excavations in the Great Plaza, part of the North Acropolis, the Central Acropolis, the main temples and many of the palaces situated in plazas in the core area of the site. Strict photographic records were taken and drawings were made of the trenches and tunnels to register everything that was uncovered, given that in certain cases the excavations were conducted at a depth of 20 m.

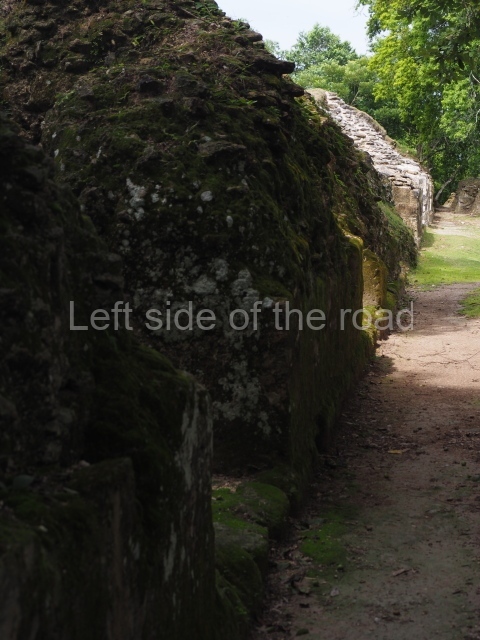

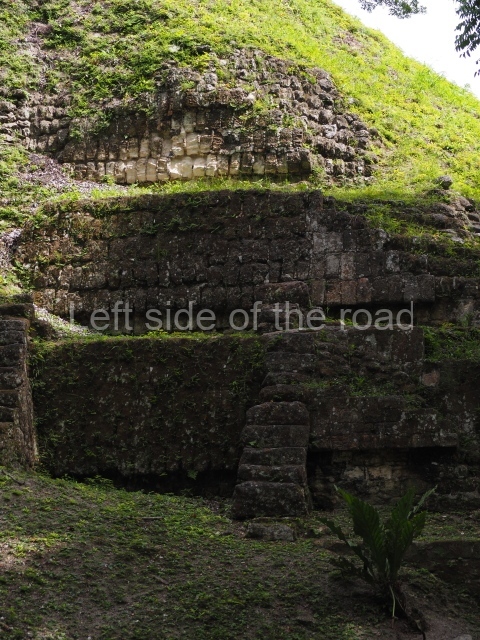

In 1958 the excavation of Temple I commenced, ending six years later; temples II, III, IV, V and VI followed. Between 1964 and 1969 the North Acropolis was excavated under the supervision of William Coe, the second project director, and priority was given to the restoration of temples I and II, the buildings in the North and Central Acropolis and other groups on the site. By 1964 Complex Q had been investigated and excavated, and was one of the first groups to be restored by George Guillemin. Subsequently, the Guatemalan Institute of Anthropology and History and the Tikal Park funded a specific project at Group G, also known as the Group of the Vertical Grooves, led by Miguel Orrego and Rudy Larios.

Between 1979 and 1986 the Guatemalan government conducted a vast research and restoration programme at the site, creating the Tikal National Project. Led by the archaeologists Juan Pedro Laporte and Marco Antonio Bailey, the works initially focused on the Lost World Group, with an emphasis on the excavation and restoration of nearly 15 buildings. The programme was subsequently extended to other areas of the site, such as Group 6C-16, the large buildings and palaces in the North Zone, and the consolidation of buildings with problems in Group F, the North Acropolis, the Central Acropolis and the Palace of the Windows. One of the final projects was jointly conducted by the governments of Guatemala and Spain and focused on the partial restoration of Temple I. The support continued with the excavation and restoration of Temple V and the investigation of the Seven Temples group is currently nearing completion.

Pre-Hispanic history

Thanks to the advances in epigraphic interpretation, we now know that the original name of Tikal was Yax Mutal and that the founder of the ruling lineage was called Yax Moch Xoc, who was followed by another 33 rulers who made references to their ancestors to demonstrate their right to the throne. The origins of this city date back to 800 BC, and the first settlers lived on two small hills, now known as the North Acropolis and the Lost World. The city continued to grow uninterruptedly for nearly 2,000 years, experiencing its golden age during the Classic period, when it was ruled by magnificent statesmen who catapulted it to the very peak of civilisation. By around 500-400 BC, the functions of the North Acropolis and the Lost World had been clearly defined, the former being used for ritual activities and the latter for observing the passage of the sun and controlling the time cycles associated with the 365-day calendar.

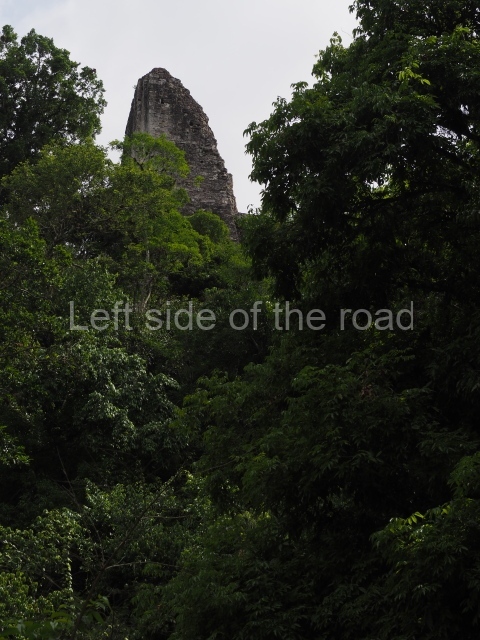

By the Late Preclassic, the two sections had been connected by a wide sacbe or causeway, forming a larger urban settlement that eventually grew into a very large city. By the 1st century AD, Tikal had become one of the most important centres in the region and its’ leaders decided to employ the arts – architecture, sculpture and painting – to create large public stages which, decorated in the fashion of a theatre, impressed the people who attended the public and religious ceremonies. The Early Classic rulers, followed by those of the Late Classic, who had much longer periods of government, expanded the city in all four directions. Each successive ruler would set in train new projects, with buildings that boasted architectural and decorative innovations, masks on the fagades, friezes on the palaces and enormous roof combs on top of the temples. Above all, however, these new constructions were painted in bright colours, seeming to come alive. Even so, not everything was glory: Tikal suffered various setbacks during the Middle Classic and then again at the end of the Late Classic when the political crisis that led to the collapse of the Maya civilisation occurred. The city was abandoned between AD 950 and 1000, although a small number of settlers continued to live in the core area and conduct ceremonies in the temples. Nevertheless, by then there was no administrative control and certainly no means with which to combat the thick rainforest vegetation that encroached further over the city every day, finally devouring it completely.

Urban planning at Tikal: site description

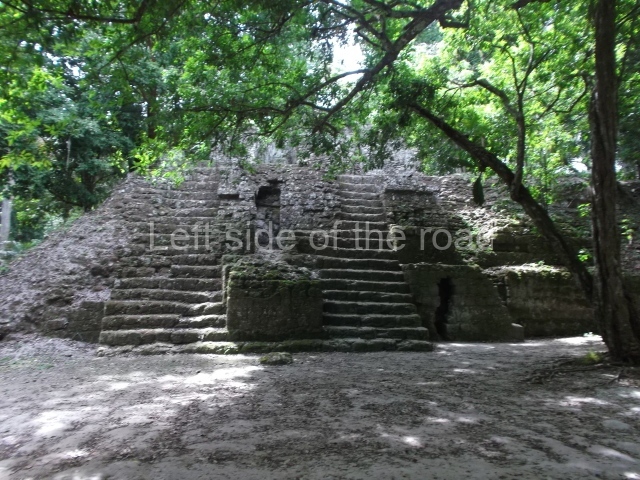

The great Maya cities like Tikal were centres of intense political and economic activity where thousands of people pursued all kinds of trades. The central section is composed of monumental groups where the elite and the ruling family lived. Here, temples, palaces and pyramid platforms were built, forming plazas with constructions on all four sides. The main groups were connected by long, wide avenues, called causeways or sacbeob, often 2 km long and 70 m wide, which were used by the people going about their daily business and also for the processions in which the king was carried on his throne, accompanied by musicians who announced his presence. Another type of architecture was the ball court, which at Tikal was in constant use. The excavations of 1980 uncovered a model sculpted in limestone showing 14 different types of buildings, including the ball court, elongated platforms and pyramidal structures, which indicates that building projects were presented to the ruler for his approval before any stones were laid.

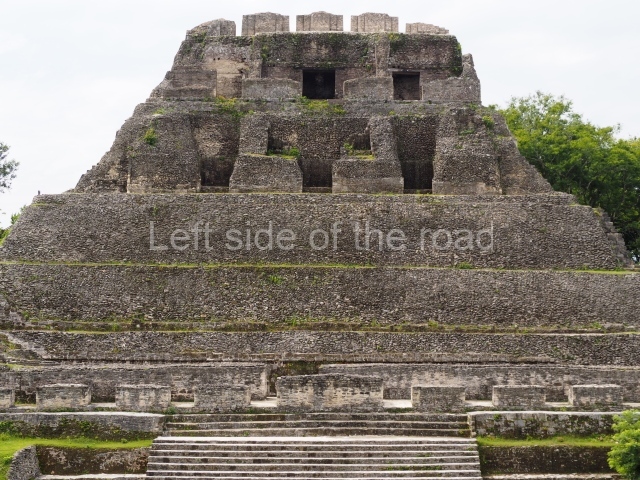

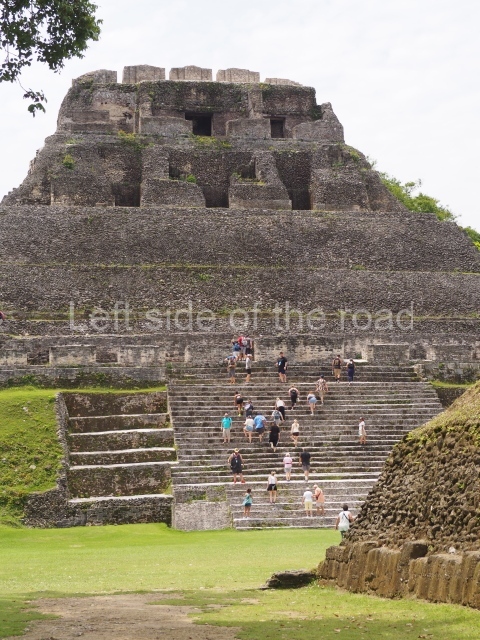

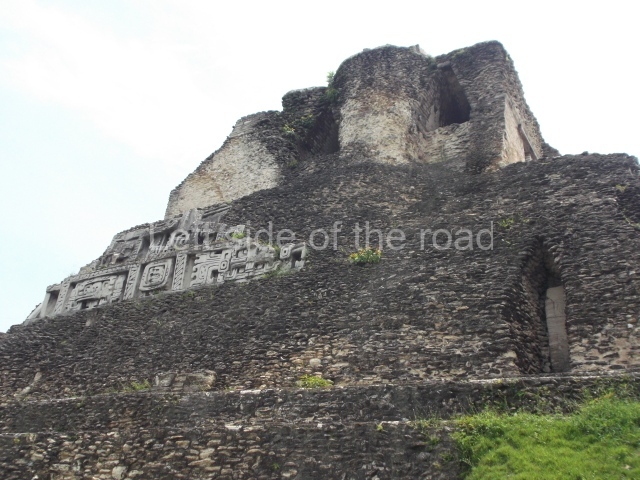

Tikal – Temple II

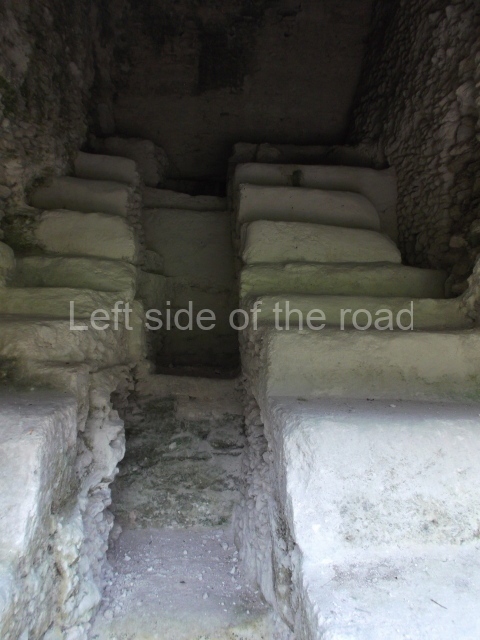

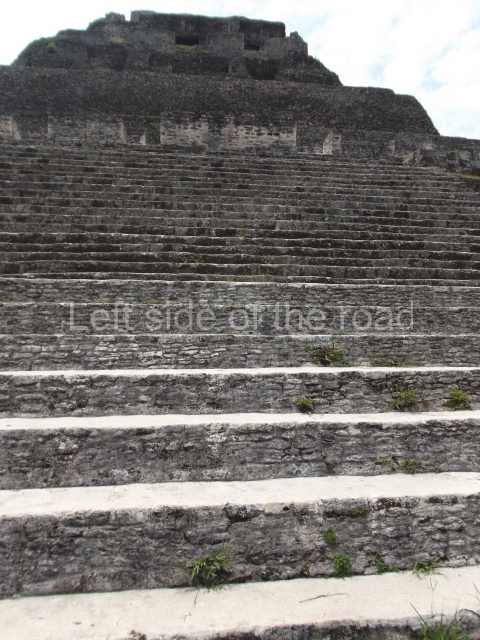

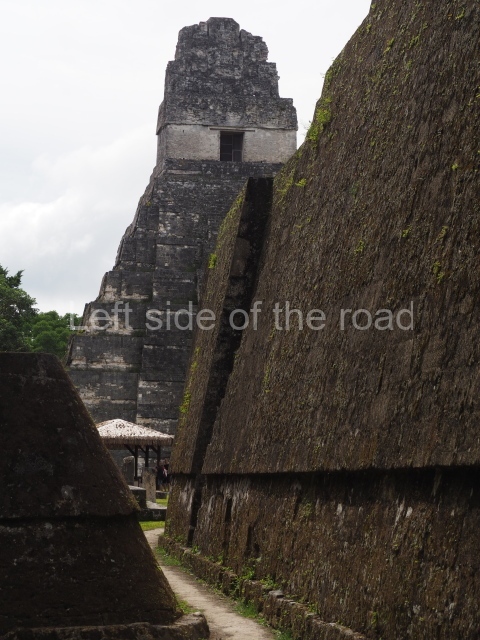

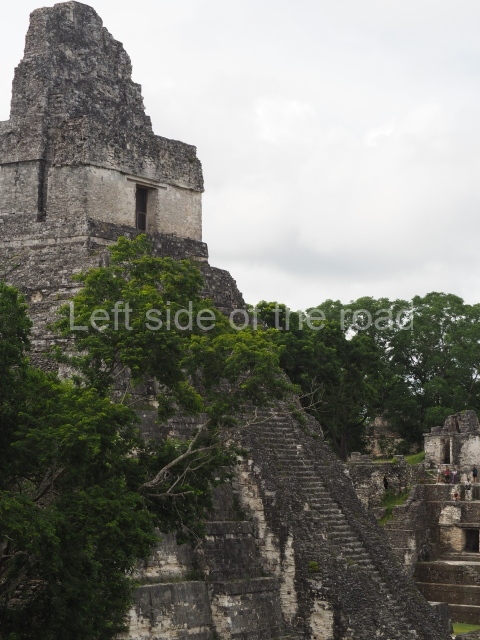

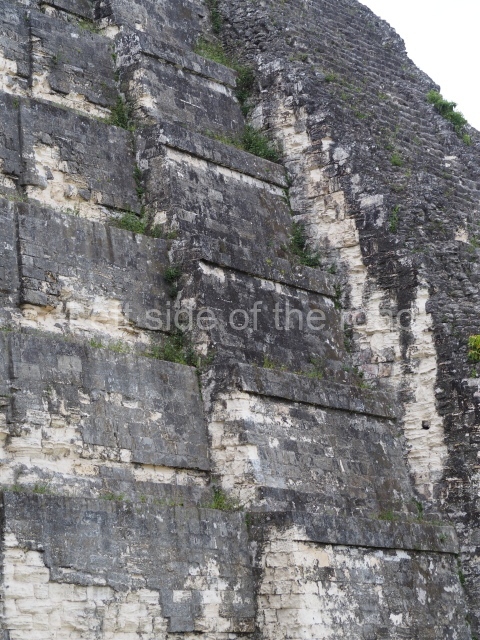

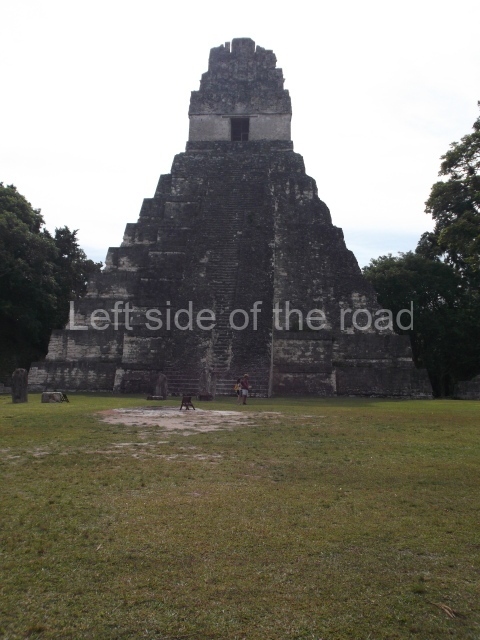

The most important groups at Tikal are the Great Plaza, the North Acropolis, the Central Acropolis, the Lost World, the Seven Temples complex, the Palace of the Windows, the North Group, the Palace of the Vertical Grooves, Group F, the various twin pyramid complexes and the six tall temples. The various buildings display architectural details such as cornices, mouldings, stairways, friezes, recessed and protruding corners, roof combs, giant masks and palaces with several storeys, all of which have helped us define the Peten style of architecture.

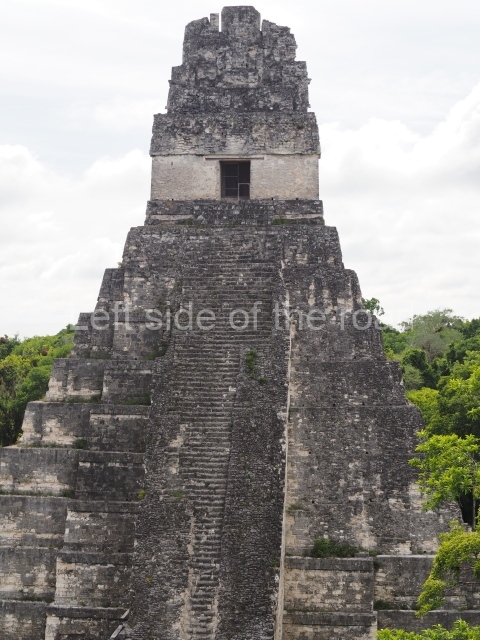

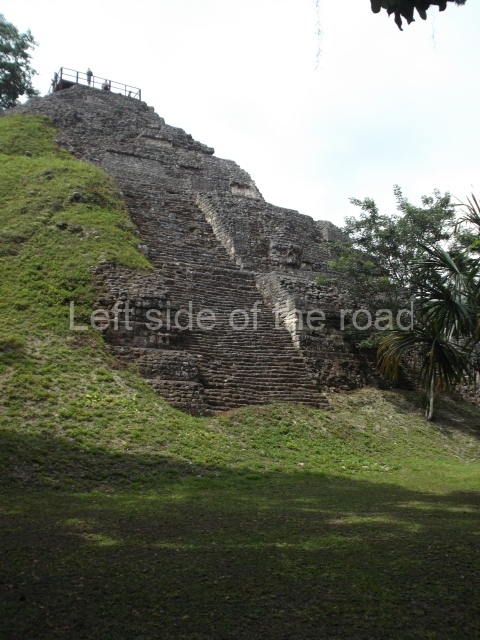

Six giant temples, standing nearly 70 m high, were built in the core area of the city between AD 600 and 830. Situated in the great plaza are Temples I and II, built around AD 700 by the ruler Hasaw Chan K’awil I, the most powerful of the Tikal sovereigns. On his death he was buried with great honours inside, accompanied by rich grave goods to assist him on his journey to the other world and for his reincarnation. Temple II was built inside Temple I and together with Temple 33 forms Tikal’s cosmic triad. However, Temple IV, built a few decades later by his son, boasts all its grandeur in its immense proportions, with the view from the top taking in everything with a radius of many kilometres.

Tikal – Temple IV

The great palaces where the king’s relatives lived were situated in the central a c r o po lis, which includes threestorey buildings, plazas, residences, schools and spaces for diplomatic receptions. Situated between this group and Temple V was a reservoir or artificial lake, which also served as a recreational area. The ball court was highly symbolic in that it recreated the struggle between the supernatural forces, and five such courts were built at Tikal; the most important one is the Triple Ball Court near the entrance to the Seven Temples group. Smaller but no less handsome architectural groups were built around the core area for occupation by middle-ranking people such as artists, craftsmen, administrators and traders. The farmers and people of more modest means occupied the outlying areas, leaving large expanses of land for crops, vegetable gardens and recreational gardens. Architecture was a means for expressing the importance of families, determined by their proximity to the ruler.

The urban planning process also involved the provision of water for the population, farming and construction purposes. The local topography was exploited in this respect: the buildings were erected on the highest terrains and the plazas had slightly inclined pavements to drain off the rain water. This was then channelled to proper drains, canals and other collection points. This system was used throughout the history of Tikal with gradual improvements to supply thousands of people. Numerous water reserves were prepared at different points around the city, although the largest were in the centre and eventually became small and highly scenic lakes where people would stroll, fish and take a boat out. During the Early Classic, the successive kings of Tikal had a defence system built to protect the city. The excavations have uncovered several sections of a moat that surrounded the city; these alone are 28 km long, but the total length is not yet known. The moat clearly had a defence function, although there were several bridges, some of them 6 m wide, to allow people to enter and leave the city. In addition to moats, the defence system also comprised several swamps, which are extremely difficult to cross during the rainy season because of the mud and thorny lianas. The defence system was built when Tikal became engaged in a series of power struggles with Uaxactun, El Peru and Caracol. Although it often worked well, it sometimes failed to prevent the invading army from entering the city. However, by the Late Classic the situation changed, giving way to a new era of peace, and the moat was filled, enabling the city to expand its boundaries to unprecedented limits and become the most important metropolis in the Maya region.

History of the rulers at Tikal

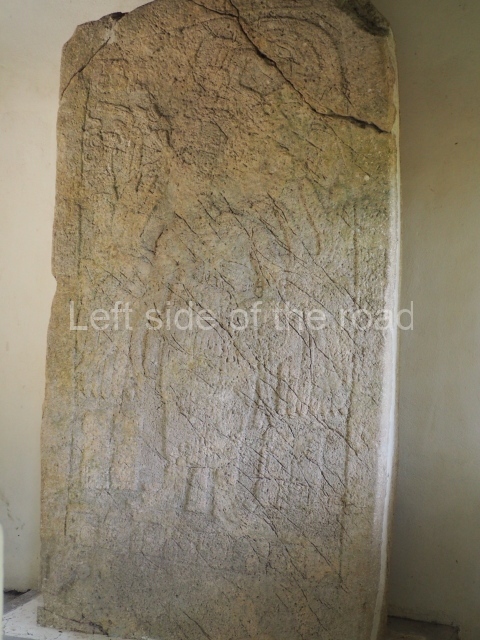

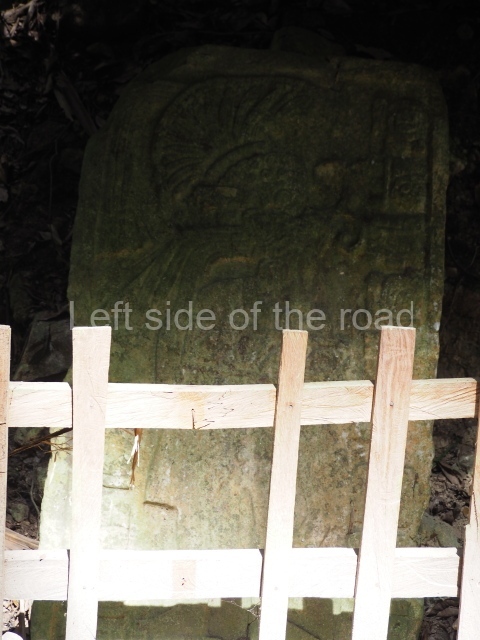

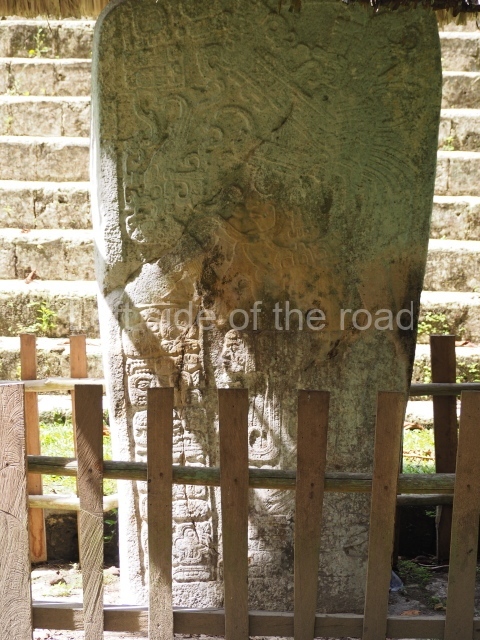

The sovereigns made reference to their origin in the sculpted monuments, lintels, carved bones and painted ceramics. They inscribed stelae with their number in the dynastic sequence, beginning with the founding ancestor. This has enabled researchers to identify 33 kings in a period of nearly 600 years. The first known sovereign was Foliated Jaguar, sculpted on Stela 29, who was the ruler in AD 292. Other better known rulers are Ch’ak Tok Ich’aak I, mentioned as the ninth sovereign (AD 360-378), who was followed by Yax Nuun Ayiin (AD 379-404), born of the union between a Tikal princess and a nobleman from the Mexican plateau, which enabled the two regions to forge stronger links. Their son Siyaj Chan K’awil II (AD 411-456) was one of the great sovereigns; he had numerous works built, inscribed his identity on several stelae and is mentioned as the 11th ruler. Next came his eldest son K’an Chitam (AD 458-486), sculpted on Stela 40 discovered in 1996, who was followed in turn by his son Chak Tok Ich’aak II (AD 486-508), as the 12th and 13th sovereigns in the line of succession.

It has been suggested that during the governments of Yax Nuun Ayiin and Siyaj Chan K’awil II, Tikal extended its relations to other regions, such as Copan, Rio Azul and Waka (El Peru). It also had ties with Teotihuacan, as demonstrated by the appearance of cylindrical tripod vases, stucco vessels with foreign iconography, artefacts made of green obsidian and buildings in the talud-tablero or slope-and-panel style. The government of Siyaj Chan K’awil II reinstated the local traditions, as can be observed in the architecture, ceramics and sculpted monuments. This king enjoyed a long reign, which consolidated the city politically and brought peace and prosperity. The two-storey palace in the eastern sector of the Central Acropolis dates from his government. As a sign of enormous respect for his memory, the palace was never altered or covered by later constructions, indicating the degree of admiration he inspired and the desire to perpetuate his memory.

As the most affluent city, Tikal created its own emblem glyph to distinguish the name of the city of Yax Mutal in writing. This hieroglyph appears on sculptures at other sites within a radius of 60 km from Tikal, such as Uaxactun, Xultun, Yaxha, Waka, Polol and Balakbal, suggesting a political dependence. It was during this same period that the two monuments with the longest glyphic texts at Tikal were built: Stela 31, which commemorates Siyaj Chan K’awil II, and Stela 40, dedicated to his successor K’an Chitam. The two stelae bear great similarities, suggesting that they were sculpted by the same person.

Another group of lesser known rulers commenced with the 14th governor, Wak Chan K’awil (AD 537-562), who is mentioned as having waged two wars with Caracol, winning the first but losing the second, thus diminishing Tikal’s power. A new era of prosperity emerged under Nuun Ujol Chaak (c. 657-679), who embarked on an ambitious revitalisation programme to return Tikal to its former prominence. Despite a turbulent government between wars, he promoted the construction of monumental works such as Temple V and two ball courts, which served to reaffirm the mythological ideas associated with the creation of the universe and the future reincarnation of the men of Tikal. His wishes were fulfilled when his son Hasaw Chan K’awiil I (682-734) succeeded him on the throne, followed by Yik’in Chan K’awiil (734-746), Yax Nuun Ayiin II (768-794), and several others.

The young Hasaw Chan K’awil I and his descendants conducted a major expansion programme between AD 679 and 830, proclaiming their status as magnificent statesmen and the promoters of ambitious public works, including temples I, II, III, IV and VI, the twin pyramid complexes, the large two- and three-storey palaces with their corbel-vault ceilings, and the extension of several causeways to link the core area with new elite groups, such as the North Zone complex. The noble families flaunted their increasing wealth by importing exotic goods from distant lands, such as jade, quetzal feathers, cotton fabrics, cacao, tobacco and salt. The 8th century is regarded as Tikal’s ‘golden age’ due to the stability achieved by its rulers, its colossal buildings and its exquisite polychrome vessels portraying palace scenes. Depicting the nobility and inscribed with hieroglyphic texts, these ceramics have shed light on the social stratification at Tikal.

Meanwhile, the discovery of several royal tombs demonstrates that the city was situated at the centre of a commercial route, as the rich grave goods include jaguar skins and exquisite pieces of bone, ceramics, jade, wood, mosaics, shells and other such items. When Yax Nuun Ayiin II acceded to the throne, he embarked on another programme of public works, including the construction of buildings and courtyards in the Central Acropolis, and his own palace – nowadays known as the Maler Palace – where an inscription of the date 4 July AD 800 was found. However, the continual wars in the region at the end of the 8th century were also recorded by means of graffiti on the walls of buildings such as the Maler Palace and others in Group G, reflecting the occupants’ concern about the increased conflicts. The pictures depict prisoners and the covered litters of enemy sovereigns being captured.

The only dated inscription for this period is AD 810, found on Stela 24, although the name of the ruler is illegible. However, the glyphic text on Lintel 2 at Temple III states that the action was conducted by the High Priest, who is accompanied by the titles K’inich Nab Nal and Chakte. At the beginning of the 9th century, Tikal still enjoyed the glory of the previous centuries, but a few decades later, around AD 850, the situation changed when the pressure was so great that every Maya city was collapsing. The last stela sculpted at Tikal dates from AD 869, although 20 years later Stela 12 at Uaxactun makes a final mention of the king of Tikal, Hasaw Chan K’awil II.

Nothing further is known about the royal family after that date. By that time, many cities had collapsed and were being abandoned, although Tikal was one of the last to be vacated. Cities did not disappear suddenly but little by little, as the thick vegetation formed a blanket over the handsome buildings of bygone days. Eventually, Tikal was lost forever.

Tikal – reconstruction

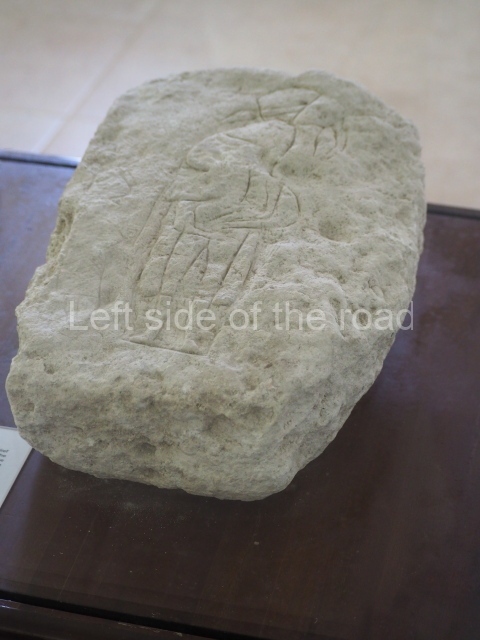

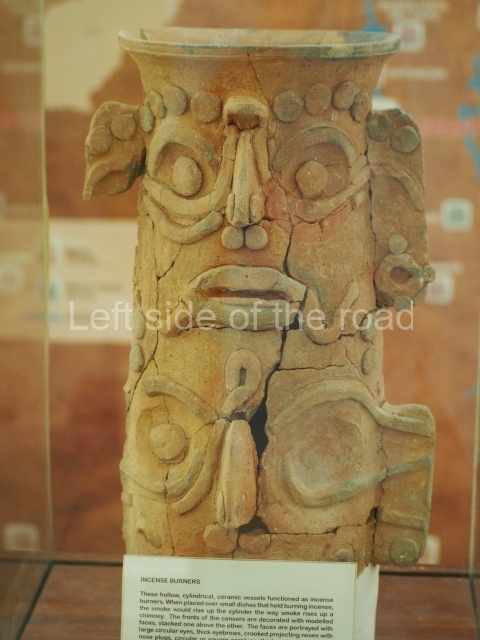

Museums

There are two museums in Tikal. The Sylvanus Morley Museum houses the ceramic vessels discovered during the excavations and provides visitors with a greater insight into the artistic evolution of the potters. The Lithic Museum, housed in the Visitor Centre, exhibits the principal stelae corresponding to the rulers of Tikal, especially those who shaped the city’s fate during the Early Classic.

Juan Antonio Valdes

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp203-211

Tikal

- Great Plaza; 2. Central Acropolis; 3. North Acropolis; 4. East Plaza; 5. West Plaza; 6. Temple III; 7. Temple IV; 8. South Acropolis; 9. Ball Court; 10. The Lost World; 11. Seven Temples; 12. Temple V; 13. Group G; 14. Temple of the Inscriptions; 15. Group F; 16. Group H.

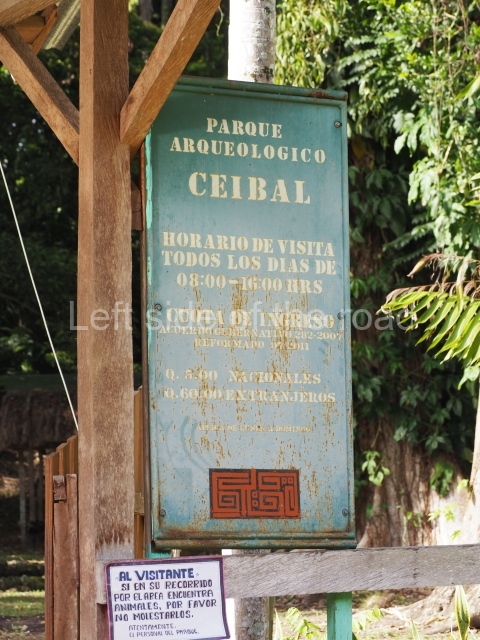

Getting there and entrance fees;

From Flores/Santa Elena. There are any amount of travel agencies that will organise tours to the site ranging from sunrise/sunset guided tours to general visits of a few hours. If you wish to do so independently then colectivos leave the top, left hand area of the new Santa Elena bus station during the course of the day. The first departure is around 06.00. The journey will take just over an hour and costs Q50 each way. 18Km before arriving at the site you enter the Tikal National Park where it is necessary for foreigners to get off and pay park entry – which is also entry to the site. Summer 2023 Q150. If you wish to stay overnight in the camping site (Q50) this also has to be paid for in advance either at the entrance to the park or online (see below). You cannot pay for such things at the site.

The site restaurant is ludicrously expensive. However, there are a couple of comedors on the right hand side of the road just before you reach the main parking area and entrance to the archaeological site itself. These might be cheaper options – didn’t see them until I was leaving.

It is also possible to book over the internet. Visit www.boletos.culturaguate.com.

GPS:

17d 12’ N

89d 38’ W