Xpujil – Campeche

Location

The archaeological area is situated due west of the village of Xpujil, on Federal Road 186 between Chetumal (120 km east) and Escarcega (150 km west). The central part of the base of the Yucatan Peninsula witnessed the emergence of Rio Bee architecture at several settlements between the 6th and 8th centuries AD. One of the sites that exemplifies this style is Xpuhil, situated at the west end of the almost homonymous town of Xpujil, the administrative centre of the municipality of Calakmul. The name Xpuhil is derived from the Yucatec Maya language and there are two hypotheses about its origin. Certain authors point out the name of a plant whose flowers resemble the tail of a feline: xpuhil, ‘cat’s tail’ (Cladium jamaicense); others believe the toponym refers to a ‘hunting place’: puh, ‘tracking, hunting’, //, ‘place of’.

Timeline, site description and monuments.

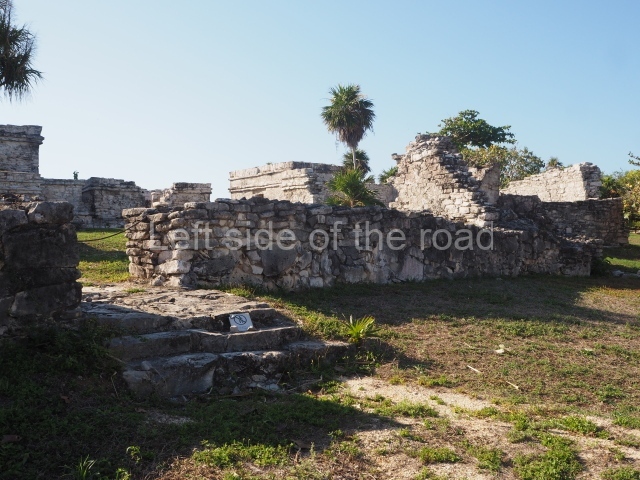

Most of the constructions visible today at the preHispanic site were built between AD 600 and 800. At the entrance to the archaeological area are several monumental mounds as yet unexcavated and covered by vegetation. The path leads to Structure IV, which is composed of a platform over 30 m long, at the centre of which rises a 5-m-high pyramid. Flanking the pyramid are two rooms with entrances on their east or main side. The exterior walls display a pair of crosses, forming a chessboard pattern; the gaps must have also been used to ventilate and cool the interior. Inside the rooms are low, wide benches, the fronts of which are decorated with symbolic motifs.

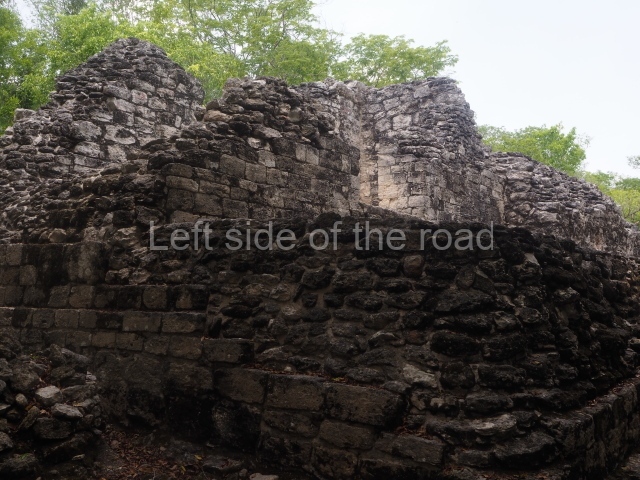

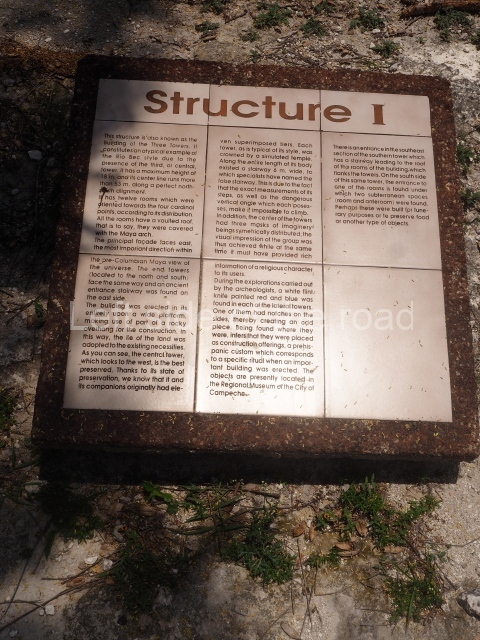

Structure III is similar to the previous one but has no pyramid. Situated on a solid masonry platform are four rooms comprising spacious benches; the centre of one of these is decorated with various small drums that are reminiscent of Puuc elements. The rooms were originally covered by corbel vaults and have been identified as the dwelling spaces of high-ranking figures in the ancient city. A little further west lies another mound, unexcavated, and on its north side another platform supports Structure II, a palatial complex with six rooms around a central courtyard. The access stairway is situated on the east side and has broad balustrades. The far west end of the archaeological area is occupied by the monumental Structure I, which stands atop a 60×30 m platform. The most outstanding elements of this construction are the three towers, two at the sides and one in the middle of the rear facade. There are 12 rooms distributed according to the cardinal points, most of them containing benches. Six rooms arranged in pairs can be accessed from the east side. The three facades have been lost and only parts of the stacks of stylised masks flanking the entrances can still be seen today. At the north and south ends of the building, behind each of the lateral towers, are two rooms. The other two rooms face west and are accessed from the west, being situated on both sides of the central tower. With their rounded corners and non-functional stairways, the towers are typical of Rio Bec architecture. The steps used to be adorned by three giant stone mosaic masks of Itzamnaaj, and each of the towers culminated in a false temple with a roof comb. The facade of these shrines repeated the ubiquitous image of the principal deity, with an open mouth surrounded by curved teeth, ear ornaments, a nose ring, volutes and associated symbols. The north and south towers must have once stood approximately 18 m high, and the central one, much better preserved, is 23 m high. The south tower has an interior staircase rising to a somewhat higher point than the roofs of the rooms.

No sculptures or stelae have been recorded at Xpuhil. During the restoration works of the north and south towers of Structure I in the 1970s, two flint knives left by the Maya builders were found at a height of approximately 15 m. The pieces were finely carved and were uncovered in the sections corresponding to the upper masks, which had been lost years earlier. One of the knives is shaped like a laurel leaf, while the other has notches along the edges and still has traces of red and blue pigments. Both pieces are on display at the Archaeology Museum of Campeche.

Importance and relations

The archaeological area open to visitors is only part of what was the ancient settlement. In certain blocks in the modern town of Xpujil, as well as in the surrounding area, it is still possible to see traces of the monumental architecture built by the ancient Maya. Even so, the urban development has practically erased them. In preHispanic times Xpuhil must have had strong links with nearby sites such as Becan and Chicanna to the west, and Payan and Okolhuitz to the east. These coexisted on the Caribbean route with the towns of Nicolas Bravo, Kohunlich, Dzibanche, Butron and Xulha

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp336-337.

1-6. Structures I to VI

Getting there:

The site entrance is only a short walk from the area that the buses and combis stop, in Xpujil town, on the main highway between Chetumal and Puerto Escarsega. Follow the road west, on the right hand side and the entrance is to the right of the pavement, just as the road starts to climb slightly.

GPS:

18d 30’ 38’ N

89d 24’ 22” W

Entrance:

M$70