Monument to the 22nd Brigade – Peze

The Conference of Peze, which took place in September 1942, was only possible as the Peze Çeta (Partisan Guerrilla Group) was so feared by the fascist invaders that they could provide a safe environment to enable the discussions on the formation of a National Liberation Front to take place. This was in a location only 20 kilometres from the capital of Albania, Tirana. As the war developed the organisational structure of the People’s Army changed and became more organised. After final liberation the efforts of these men and women started to be recognised throughout the country and hence the Monument to the 22nd ‘Shock’ Brigade.

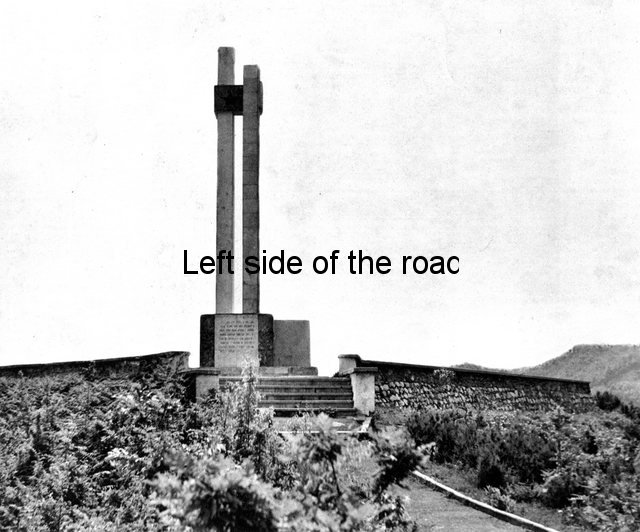

The park that was established in the area where the Peze Conference took place is only small but has one of the biggest concentrations of monuments to the past than virtually anywhere else in the country. Just a matter of a few metres up the hill from the Peze Conference Memorial can be found the memorial to the 22nd ‘Shock’ Brigade and across the bridge the Peze War Memorial.

I’m sure that in the Socialist past the park would have been pristine and a pleasant place for Tiranans to have visited on holidays and at weekends – still now there are restaurants that must depend upon day visitors. However, you be lucky to arrive and not find the place strewn with rubbish. On my visit the only thing keeping the grass down was the flock of sheep.

Whilst saying that the monument itself was in a reasonable condition, just the surroundings looked tacky and the lights that at one time would have made it possible to walk around in the evening looked as if they had not seen electricity for years.

The actual 22nd Brigade was formed relatively late in the war, on 18th September 1944, so was really created to better structure the final push to liberate the country from the German Nazis.

These ‘Shock’ Brigades, we would probably now call them Guerrilla Units, were highly mobile, hit and run organisations that were self-sufficient but when needed would unite with other Brigades to concentrate the necessary force to destroy large columns of the enemy, as happened in Mushqete only a few days before the liberation of Tirana.

Monument to the 22nd Brigade

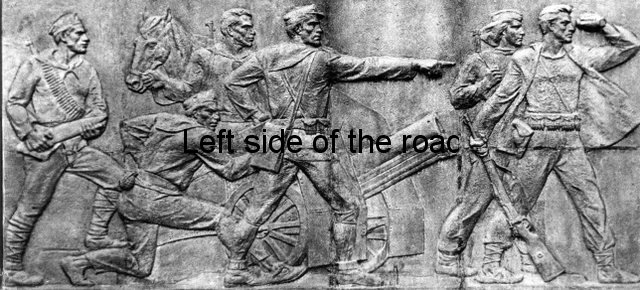

The Monument was created by Mumtaz Dhrami and Kristo Krisiko and its official name is ‘Monumenti i Pezes’. It was completed in 1977, the same time as the War Memorial and the Monument to Heroic Peze. It consists of a concrete wall that curves inwards on the right hand side. At the left hand side the wall is at, more or less, knee height of the figures (just slightly bigger than life-size), where there’s a group of nine marching Partisans. The wall gently slopes up and at the far right becomes a series of pillars, each higher than the one before.

At the head of the marching group is a woman who holds the pole of the Communist flag in both her hands, slightly in front of her body. The flag flutters above and behind her head and as is common on such monuments the flag bears the symbol of the double-headed eagle with a star above the heads. As I have mentioned before the women in these statues are always armed and her rifle hangs behind her and she has a bandolier of bullets around her waist. She wears a cap with the Communist star at the front and her long hair has been gathered together.

Behind her there’s a row of three males. The outside one wears a heavy greatcoat and carries what looks like a light mortar over his left shoulder. This is likely to be a 2” mortar as this could be easily carried by one man, weighing as it did in the region of 5 kilos. He has a water bottle attached to his belt but carries no other weaponry.

Both the British and the German armies produced such a weapon so this could either be one liberated from the Nazis or part of the weapons drops that the Partisans gratefully received (but which the British grudgingly sent) when the Allies realised the Communists were by far the most effective fighting force of the different groups in opposition to the fascist invasion.

The other two in his row carry heavy calibre rifles on their backs, the end of the barrels appearing behind their heads, the inside one becoming part of the folds of the flag. The three of them are wearing caps with the red star attached at the front.

Behind them is another row of three males. The one on the outside has what looks like an Italian FNAB-43 submachine gun in his downwards extended right hand. The Albanian Partisans acquired many of their weapons from the enemy,a tradition followed by most Communist guerrillas ever since (although few in the Vietnamese forces against American intervention even bothered to pick up the US made M16 rifle when they had the AK47). His left hand is against his chest gripping what could be some kind of sack hanging behind him.

The Partisan next to him is different from the rest in that he is not facing in the direction of the march but is either looking behind him or at the viewer. He, and the third one in this row both have heavy calibre rifles on their backs. They are all wearing head gear with the star but whereas the first two have a different version of the caps the man on the inside wears a fez.

Behind them there’s a man and a woman, the last of the group. He has his right hand gripping the barrel of a heavy machine gun which rests on his shoulder. He has an ammunition belt around his waist and on his right hip there’s a British Mills bomb, a fragmentation grenade. He also wears a cap with the star – this symbol of being a member of the Communist Party being more evident here than on some other such monuments.

The woman at the back is a bit of a mystery. She doesn’t seem to be in uniform, her hair looks like it would be if she were working in the fields and she doesn’t seem to be carrying any weapons. She is the only one of the group who is not wearing a hat.

In front of the last two rows of Partisans is a small field gun. This was probably a very popular weapon for the Partisans as it was of a size that could reasonably be manoeuvred along the narrow mountain paths and over the high passes. This is exactly the same sort of cannon that was used at Sauk to bombard the traitors of the Quisling Assembly at the Victor Emmanuel III Palace.

On the ground, close to the wheel of the mountain gun, is a discarded Nazi helmet which is resting on what could be a heavy machine gun magazine. This represents the defeated fascist invaders.

This group is marching towards a plaque, the words translating to: ‘Honour the Martyrs of the XXII Shock Brigade’

Further to the right is where the monument breaks up into columns, I assume representing the mountains of Albania. On these four columns are the names of over a hundred Partisans from the Peze area who lost their lives in the National Liberation War.

This monument has recently been whitewashed but unlike the Monument to Heroic Peze different elements, such as the stars on the flag and caps or the eagle on the flag have not been highlighted. It’s difficult to work out what the idea is behind this policy of whitewashing. To the best of my knowledge the intention of the sculptor/s, in virtually all the monuments I’ve visited and seen, was for the unadorned concrete.

The whitewashing, as here, is not as careful and conscientious as it could be and always has the potential of filling in some of the detail of the figures, especially as they have been neglected for much of the last 25 years.

At the same time the rest of the structure looks dirty. The concrete might look brighter but any marble plaques with slogans or the list of the names of the fallen, were not cleaned up at the same time (this can also be clearly seen at the Mushqeta Monument at Berzhite). The rationale for this ‘clean-up’ is difficult to understand not the least as it seems to be totally random and not part of any organised and planned programme.

GPS:

N41.21561799

E19.70189701

DMS:

41° 12′ 56.2248” N

19° 42′ 6.8292” E

Altitude: 100.7m

Practicalities.

Getting to Peze is not difficult but it does require a little bit of pre-planning and a bit of organisation as the starting point in Tirana is slightly out of the centre and it’s not a particularly frequent service. The bus stop is on Rruga Karvajes, opposite the German Hospital and just a few metres east of Rruga Naim Fresheri. The journey takes between 45 minutes and an hour, depending upon traffic and the driver, and costs 50 lek each way.

Departures from Tirana: 09.00, 12.00, 13.30,

Departures from Peze: 10.00, 12.45, 15.15

These times can be flexible in the sense of leaving later than stated. I suggest you allow at least an hour to explore the park. There are a number of bars and restaurants close to where the bus turns around so you can move quickly if necessary.