Peze War Memorial

The third major monument in the Peze Conference Memorial Park is the cemetery to those from Peze who fell during the anti-Fascist war of Independence. The Peze War Memorial is a short distance from the main area of the park and you could be excused for not knowing it’s there.

At one time this area must have been a pleasant place to spend some time away from Tirana. In the past the capital itself was not a busy, noisy and polluted city (as it has become now) and the contrast wouldn’t have been so great. Now that Tirana has all the negative aspects of capitalism such oases of quiet should be at a premium but that doesn’t mean that they are looked after.

On my recent visit the waste bins hadn’t been empties and if the litter hadn’t just been left on the grass the wind would blow the plastic bags from the overflowing bins and were everywhere. This includes the small river that runs through the park – you really wouldn’t want to be a river in capitalist Albania, see, for example, the fate of the River Kir in Skhoder.

The Peze War Memorial and cemetery is across a bridge over the river and it’s more than likely there will be some kind of makeshift fence that gives the impression that you are going into someone ‘s field. The cemetery is slightly around the corner, up on the right and with the trees in full leaf it’s not possible to see exactly what’s there.

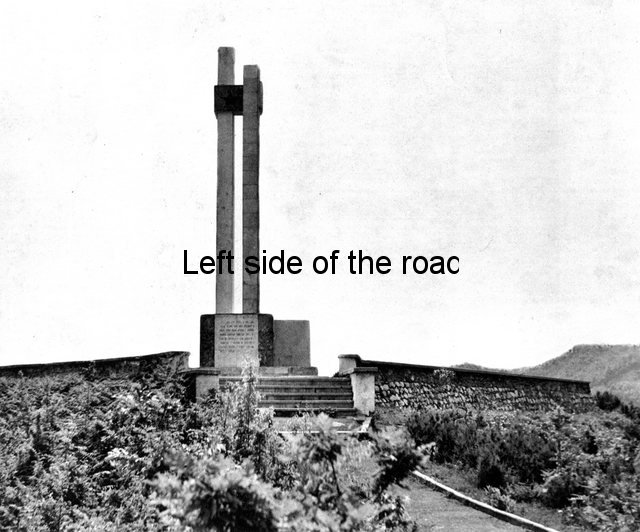

However, just go through the fence (only bits of scrappy string hold the ‘gate’ closed and once on the other side of the bridge you’ll see the monument sitting against a backdrop of pine trees, which you reach after going up a flight of low steps.

This is the work of the sculptors Mumtaz Dhrami and Kristo Krisiko with Nina Mitrojorgji as the architect. The official name is ‘Monumenti i vendosur në varrezat e dëshmorëve në Pezë’. It was unveiled in 1977, the same time as the Monument to Heroic Peze at the junction of the Peze-Tirana-Durres road. They must have been part of a joint project (together with the Monument to the 22nd Brigade) and it’s possible to see similarities in the style and imagery.

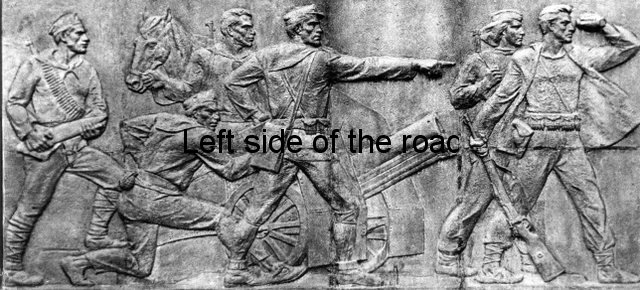

The bronze part of the monument is embedded into a concave mass of white concrete. (There’s been a lot of painting of the Socialist period monuments recently and I’m not always sure if they were originally designed to be whitewashed or if the bare concrete was considered to be more aesthetically appropriate.) The bronze section is in two parts. The large concave section is decorated in bas-relief and in front of that (but also attached) is the statue of a group of four partisans on top of a plinth.

These statues are not complete figures, the male partisan at the front is only shown from a point midway between his knees and thighs and of those behind him there is more as they are raked so that we can see all of their faces.

The prominent, young male is dressed in what would have been the partisan’s uniform, wears a cap with a star and has what would have been a red bandanna around his neck. In his right hand he holds the top of the barrel of a rifle, the butt of which would be resting on the ground (unseen). Across his right shoulder there’s a bandolier (broad ammunition belt) and he wears another around his waist. On his right hip there hangs a British made Mills bomb (a fragmentation grenade). Over his left shoulder is a narrow strap that is attached to a small satchel that hangs just behind the grenade. His left hand is clenched into a tight, angry fist. He is looking straight in front of him, his head held high and proud.

Standing at his left shoulder is an older woman. She is very reminiscent of the depiction of the female on the Peze junction memorial, on that part that looks in the general direction of Tirana. She is not in uniform but wears traditional peasant dress with a hood pulled over her head. As I’ve said a number of times now the women are always armed (including in the description of the Albanian Mosaic on the National Museum) and she has a rifle slung over her left shoulder. She is looking slightly to her left, the only one of the group not looking straight ahead.

Behind her, and head and shoulders higher, is another young man. He is also not in any formal uniform. He has his sleeves rolled up, holds the top of the barrel of a quite significant machine gun in his left hand and his right hand is clenched in a bent arm salute, his hand directly over the head of the partisan soldier at the front of the group. He doesn’t wear a hat. He is looking in the same direction as the partisan.

The last of the statues is of an older man. His face looks over the right shoulder of the forward male. He has a bushy moustache and wears a fez. His right arm, sleeves rolled up, is also bent and his fist clenched in a revolutionary salute. He is also looking forward but there’s no evidence that he’s armed.

The plinth upon which they are standing carries the slogan: ‘Honour to the Martyrs of Heroic Peze’

As a backdrop to this group there’s a large five-pointed star (only three points are visible) on the concave bronze background.

Here we have the representation that the war against the Fascist invaders was a war that was fought, and won by ALL the people. A National Liberation War is not like those wars fought by the mercenary armies of capitalist/imperialist nations. As Mao Tse-Tung said: “The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea” and that was how the Albanians were able to defeat the invader. And it meant the involvement of all the population, regardless of age or gender.

There are a lot of stars on this monument. Two of them have letters on them. One on the left hand side of the group has the letters VFLP – which we have already seen on the Peze junction monument, “Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!” (“Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!”). Another, on the right hand side of the group has the letters PKSH – Partia Komuniste Shqiptare (Albanian Communist Party) which was later to become the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA).

Immediately to the right of the group on the bas-relief is the depiction of a young family, a mother, father and child. Both the man and the women are armed (with rifles slung over their shoulders) but it’s only the woman who is in the uniform of the Partisans, wearing a cap with a star and the red neckerchief. Her fingers of her left hand are tucked behind the strap of her rifle and she holds something hanging down from her right hand but I’m not able to work out what it is, it looks like a bottle/container of some kind. (See comments below for another interpretation of the groupings in this part of the monument.)

What’s a little bit different (and unique, so far, in my travels) is that it’s the man who’s left holding the baby. He is static, looking out at us, but she is marching towards the left hand edge of the tableau, as if marching to war. However, this doesn’t mean that she is doing the fighting and he is the stay at home dad as he is also armed and is obviously a fighter as well as she.

Next to them, and taking up the space for the rest of this side of the monument, there is a lot going on. In the front, at the bottom, is another family group. Although looking in the direction of the battle, of the front, of the attack, the man has his right arm around his wife and she is pressed tightly against his chest, her right hand on his shoulder and a bag hanging from her left. She is dressed as a peasant woman of the time, her hair covered with a scarf.

The man is not in uniform and his sleeves are rolled up and he is clutching a rifle by the bottom end of the barrel. Grabbing hold of the wooden butt of the gun is a young boy. Whilst he is standing with his back to the action that is drawing the attention of his father he has his hands on the gun as he looks back over his shoulder as if to say ‘give me the gun and I’ll go and fight the invader’. The woman is wearing what would now be called flip-flop sandals and the boy appears to be barefooted. Is this the farewell before he goes off to the mountains?

Behind this family group is a single male. He’s looking in the same direction as the others on this side of the monument but he is not pointing his gun (which looks like what I think is an Italian FNAB-43 submachine gun – the same as one partisan is carrying in the 22nd Brigade Monument) but brandishing it high above his head, as a challenge to the enemy – ‘we are going to get you’ he seems to be saying.

The next group, slightly higher and at a diagonal to the family, is a group of three males, of different ages and, by their dress, from different parts of the country. Two of them have their guns at the ready as if they are about to, or have just fired at the enemy. The third, the moustachioed and wearing a fez, for some reason isn’t armed and merely has his right hand clenched.

This is not the first time that groups of three have appeared in Dharmi and Krisiko’s work. I don’t know if that this is just a fad that they have or whether it holds a greater significance. (See the Heroic Peze Monument.)

Next up is a single male. He is a Communist as we can see the star on his fez. He’s full on. His right arm is high up above his head, in which he holds some sort of grenade he’s about to throw – I don’t recognise the type. (This looks similar to what the young mother mentioned before has in her hand.) This Communist has an FNAB-43 submachine gun in his left hand, ready to put it to work once the grenade has caused its havoc.

Next, and higher up, is a group of four (three men and a woman) partisans, all in the act of firing at the enemy, the three with rifles have them up to their faces in the act of aiming and one with a heavy machine gun on a tripod. Three of this group wear a star on their caps.

The remaining two partisans on this side show that victory does not come without casualties, without sacrifice. At the highest point of the bronze we have a female Communist (star on cap) with her left hand under the arm of a wounded male comrade. He is unable to stand on his own and she keeps him up. His left hand is on his rifle and she grips the same rifle by the barrel, whilst looking in the direction of battle. He might have fallen but there will always be someone ready, and willing, to pick up the rifles of the fallen to continue the struggle.

There’s a different dynamic on the other side of the group of four. The only one who is looking in the direction of the battle in which his comrades are involved is the standard-bearer. He holds the flag pole, the banner itself fluttering in the direction of battle, with the star over the heads of the two-headed eagle. Whilst his left hand is holding the flag pole in his right he holds a rifle and has a bandolier from his left shoulder.

The rest of the bronze on this side is taken up with a group of ten partisans.

The front group is made up of four males, all armed. Three of them are holding their rifles by the barrel whilst the butts are on the ground, but all these rifles are held so that they are very close together. One of the group looks like a teenager, he is smaller than the others and one of the men has his left hand on the young lad’s shoulder in a comforting, supportive manner. However young he might be the lad is armed as well as the others. Three of this group are wearing caps with the red star (including the youngster).

I’m trying to work out what they are doing, looking at. On the other side virtually all the attention is paid in one direction, where the conflict is taking place. On this side the group has no common point of interest. Although the four individuals are obviously together, the uniting of their weapons tells us that, where they are looking does not indicate unity, at least to me. Possibly it’s a meeting with a commander, who would be the one who is looking out at us, and that’s the reason the others are looking inwards.

Behind the four principals we only see the heads of the other six fighters. As with the front group there’s no common direction of attention.

On the far right we have a hatless fighter, the top of the barrel of his rifle peeking out behind his shoulder. Next along is a Communist partisan woman, with a star on her cap and her rifle raised above the heads of the males in the forefront. Both these are looking out at the viewer.

Behind the woman there’s a group of three males, of different ages (again stressing the fact that war is not just a matter for 19-20 year olds) looking generally over to their left. Things get squeezed a bit here and above their heads can be seen the tops of the barrels of various weapons and what appears to me to look like a pitchfork. This suggests two things. The first is that any weapon can be used against an invader. Secondly, even though the PKSH was a workers party Albania at that time was also a country with a predominantly peasant, agricultural population. Collectivisation and the establishment of State Farms after liberation would alter that class structure but the monument represents the situation in the country pre-1944.

The remaining male on this side looks out at the viewer, hatless but with his right fist clenched in the revolutionary salute. It might be useful to stress here that this group is collected together under the star with the letters of the anti-fascist slogan, VFLP.

This monument is in a very good condition, the only signs of wear being on the white concrete base which shows the stains from the pine trees behind. The condition of monuments throughout the country varies. This varying situation depending, I would have thought, on either the ruling political force in the locality as well as devoted individuals who take it up themselves to respect the memory of the past and the contribution made by the men and women who gave their lives for the liberation of their country. A case where, institutionally, this looks like the case is the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Berat.

This monument exists as a celebration of those from Peze who lost their lives in the war against first the Italian and then the German invaders. I don’t know if all the tombs are actually the final resting place of those who died but I’m sure there would have been a great deal of effort after the war to collect the remains of as many of the fallen as possible and place then close to their home town.

Before 1990 all of the cemeteries throughout the country would have been in a pristine condition. On significant dates relating to the war there would have been memorial services where, traditionally, children would place flowers on ALL of the graves. This served a double purpose. It ensured that those who might not have had any living relatives were not left out in the commemoration and also served as a lesson to the young to remember, recognise and respect what others had done to ensure their freedom.

On my visit in November 2014 it was not pristine but there had obviously had been some attempt to tidy the garden and at least the marble slabs on the steps hadn’t been looted as they had been at Korce, for example.

The cemetery is also in a very pleasant location. The village of Peze itself is at the head of a valley which is wide close to the Tirana-Durres road but which narrows significantly at the village. The cemetery is on one side of this narrow valley looking out to the fields that, during the Socialist period would have been full of activity but which are now is only worked sporadically.

GPS:

N 41.21647504

E 19.70247201

DMS:

41° 12′ 59.3101” N

19° 42′ 8.8992” E

Altitude: 109.7m

Getting to Peze by public transport:

Getting to Peze is not difficult but it does require a little bit of pre-planning and a bit of organisation as the starting point in Tirana is slightly out of the centre and it’s not a particularly frequent service. The bus stop is on Rruga Karvajes, opposite the German Hospital and just a few metres east of Rruga Naim Fresheri. The journey takes between 45 minutes and an hour, depending upon traffic and the driver, and costs 50 lek each way.

Departures from Tirana: 09.00, 12.00, 13.30,

Departures from Peze: 10.00, 12.45, 15.15

These times can be flexible in the sense of leaving later than stated. I suggest you allow at least an hour to explore the park. There are a number of bars and restaurants close to where the bus turns around so you can move quickly if necessary.