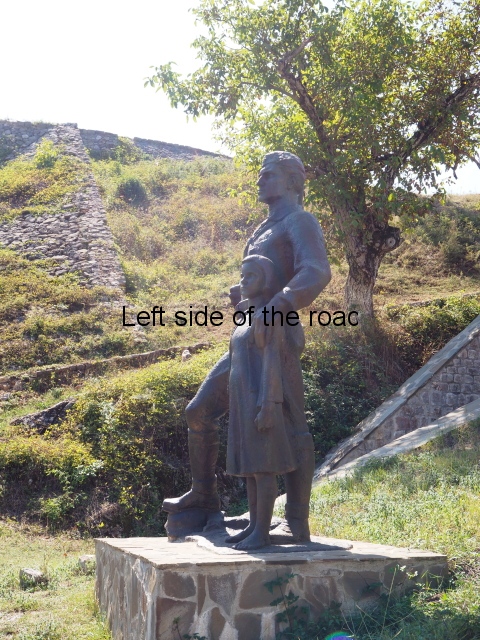

Partisan and Child, Borove

The statue of a Partisan and Child, just beside the main road passing through the small village of Borove in the south-east of the country, is one of the most charming of Albanian monuments but its charm obscures a much darker story. That story is less obvious now than it was in 1968 when it was created, in a different location and part of a bigger tableau.

It is the work of two sculptors, Ilia Xhano and Piro Dollaku, and the original design incorporated a panel depicting people from the village as well as a tall lapidar with a star at its summit. This was erected on the rocky outcrop upon which the Martyrs’ Cemetery was built, across the main road from the bulk of the present village.

I won’t go into a great detail here (I’ll leave that for when I write about the description of the present arrangement at the cemetery) but it will make sense of what follows if you know that the original monument was constructed to commemorate those who died at the hands of the Nazis on July 9th 1943. (Such events making the construction of the German War Memorial in Tirana and insult to their memory.)

At that time Albania was under the nominal control of the Italian Fascists but the German variety were in Greece. A few days before the massacre a German army convoy used Albania as a shortcut to join other forces in Greece. As it passed close to the village of Borove it was attacked by a unit of the Albanian National Liberation Army. A battle ensued for a few hours but eventually the convoy was able to continue along its way.

The German High Command decided to pay the Albanian people for their impertinence in defending their national integrity and three days after the attack on the convoy returned to the village and killed all they could find, as was usually the case in such massacres in wartime, mainly women, children and old men. Those who weren’t shot were herded into the village church and then burnt alive. A total of 107 people were killed that day. Before they left the Fascists burnt down or otherwise destroyed every building in the village.

This herding of the people is what is depicted on the panel of the original monument. (It still exists having been placed on the wall at the entrance to the cemetery.)

If we now return to the statue we find that we have a different story and I’m not sure why the decision was made to change the narrative. I have no exact date when the changes were made but from other indicators probably sometime in the mid-1980s. It was also probably at that time that the plaster sculpture was replaced by the more substantial bronze version that we see now.

Before the story was clear. On the left the panel depicting the last moments of some of the villagers. In the middle the column with the star at the top symbolising the victory of the Communists in liberating their country. On the right the Partisan and Child symbolised the fact that it was the Partisan Army that threw the Fascists out of the country, the rifle on his shoulder emphasising that what had been gained by the gun could only be defended by the gun (as I suggested in my description of some of the images on the Gjirokaster Education monument) and his protective hand on the young girl’s shoulder making references to the future.

But in its present location that narrative is not there. Socialist Realist Art is not just about the image but the message that the image is attempting to communicate. It’s still a fine statue. It still has meaning – but that meaning has been lessened.

As in most partisan statues he has the star on his cap and what would have been the red bandana around his neck declaring that he is a Communist. He’s armed and prepared and willing to fight, he did so in the past he will do so in the future. His right foot is pressed down on a German Nazi soldier’s helmet symbolising the crushing and destruction of Fascism (although we should always remember Bertolt Brecht’s words ‘Do not rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.’). His right hand holds the strap of his rifle, which is slung over his shoulder, and his left hand rests on the girl’s shoulder. This is indicating a willingness to protect her (and by inference all other children and the construction of Socialism) as well as a passing on of the task of fighting for, and defending once gained, that which was offered to the Albania people in 1943 with the winning of independence. Now, I accept, that some of that younger generation didn’t come up to the task but that’s by the by.

In its original context this protective and caring gesture had another meaning. Of the images on the panel there are two women, one cradling and using her own body to protect a babe in arms and another clutching a young boy close to her body. They were unarmed, they died. Mirroring this gesture the Partisan is saying I, and the future, will not die so easily.

I first saw this statue on my first visit to Albania in 2011, fleetingly, only for a matter of a second or so out of the corner of my eye as the bus passed through the village. Having had the chance to study it on a quite, sunny and warm, late May afternoon it lived up to its promise.

Borove probably doesn’t have many more people living there now than it did at the time of the massacre in 1943 but it boasts incredibly fine examples of art from the Socialist period. There’s a dignity emanating from this couple. They are confident, they know what they need to do, they know that it won’t be easy but they are determined. Both stand straight and firm, heads held high, looking to the future.

It’s also unique (at least so far from my experience) in that this is the first sculpture which places such a young child (and a female one at that, as I wrote in my post about the project in general, one of the aims of Albania’s Cultural revolution was to emphasis the role of women in society, past, present and future) in such a prominent role. There are children in other monuments but not as the main player. Here she is smaller but still an equal with the soldier.

I may not be sure why the original sculpture was broken up but I can see logic in placing the Partisan and Child where it is. Most Martyrs’ Cemeteries had a small museum eventually connected to them. I’ve not encountered one that is still intact and many of them were looted in the 1990s – whether by enemies or friends of Socialism is unsure. Directly across the road from the sculpture is a space, right next to the hill, that shows signs of a recent renovation of the windows and doors – certainly later than 1990. Whatever work was started it was put on hold some time ago. If it was a ‘working’ museum the statue opposite the entrance would make sense.

New position of the statue

Partisan and Child – Borove – New position

On a visit to Borove in the early autumn of 2019 I was shocked to see, when I came into the village from the direction of Erseke, an empty plinth where I expected to see one of my favourite Albanian lapidars.

However, it was relief that on looking to the other side of the road I saw that the Partisan and Child had be re-positioned and now stands on a lower plinth in front of the small structure under the martyrs’ Cemetery mound. As it now stands on a lower plinth it’s now possible to have a good walk around the statue and fell the texture of the bronze.

I assume the building, that has never been anything but a dirty and empty room, was originally designed as a museum but if it ever operated as such I don’t know. The road from Erseke to Permet is a particularly quiet road, even by Albanian standards. Few vehicles pass during the day and even fewer would even know, or notice, the statue and realise there’s a large memorial cemetery atop the mound around which the road winds as it leaves the village and heads south. And on the handful of occasions I’ve been to Borove I’ve never actually seen anyone walking in the village. Nonetheless it would be paying respect of the murdered villagers if there was some sort of memorial in the form of a museum inside the building.

The lack of a museum, which tells the story of the event during the national Liberation War, means the slaughter of the villages by the Nazis in retaliation for a Partisan ambush in the hills above the village is being forgotten. The only time the people are remembered is when the German Embassy makes a meaningless gesture of atonement on the anniversary of the murders on July 9th – although I’m not sure if that still takes place every year.

Location:

If you are heading south, coming from the direction of Erseke, the sculpture is (now) on the right hand side as you come into the village of Borove, in front of the abandoned museum below the cemetery mound. Blink and you’ll miss it as the road twists and turns as it goes around the rocky outcrop of the cemetery and then leaves Borove behind.

GPS:

40.310928

20.65264103

DMS:

40° 18′ 39.3408” N

20° 39′ 9.5077” E

Altitude:

967.3m