Soviet Army Monument – Иван Иванов

Soviet Army Monument – Sofia

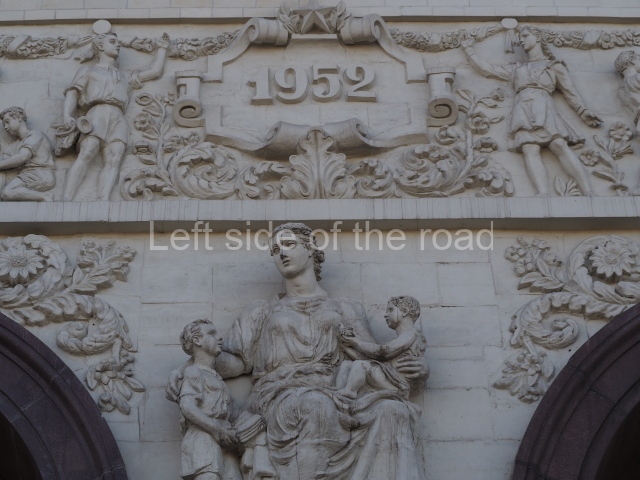

Possibly the largest extant sculptural work of Socialist Realism in Sofia, and quite possibly the whole country, is the Monument to the Soviet Army which was commissioned and erected in 1954 on the occasion of the 10 anniversary of the Liberation of Sofia by the Red Army.

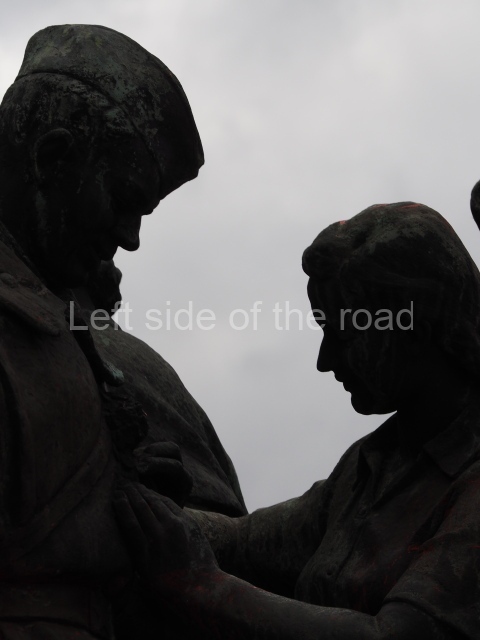

The principal monument was a group sculpture of; a Red Army soldier in the centre, with his rifle held high above his head in his right hand; to his right there’s a young Bulgarian woman holding her baby; and on his left there’s a Bulgarian man. This trio was standing on a 37 metre high pedestal which is reached by a series of stepped platforms from the edge of the complex which starts near the main road.

It is ‘was’ rather than ‘is’ because this particular element of the monument was removed in December 2023. In theory this will eventually be given a place in the garden of the Museum of Socialist Art. It had not appeared there in April 2024 and the reason for the delay is unknown, possibly because it would be in need of some cleaning and restoration. It is hoped that is the only reason for the delay and that reactionaries in the Bulgarian political community are not using it as an excuse in the hope the delay will erase the sculpture from the public consciousness.

Although this trio might have been the focal point of the monument it is by no means the only element of complex.

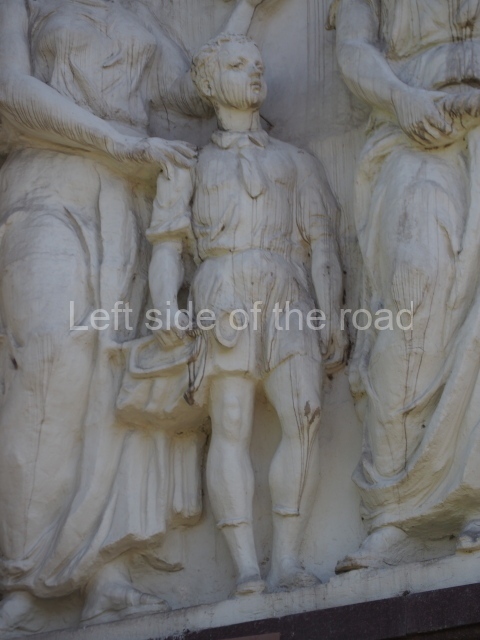

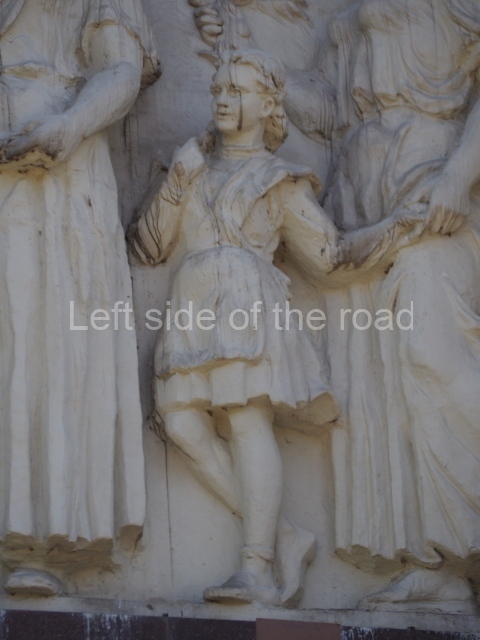

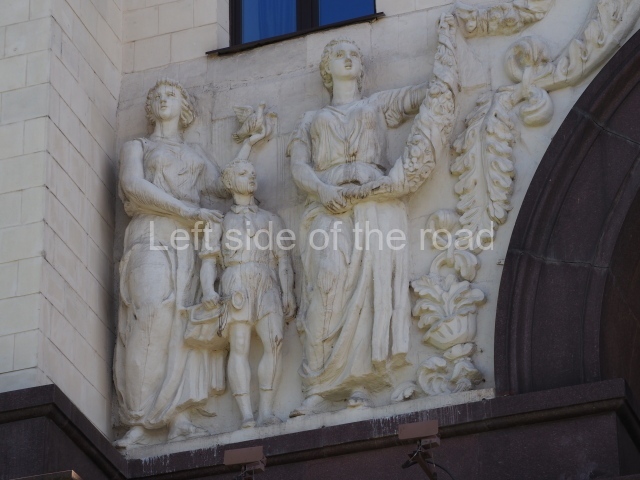

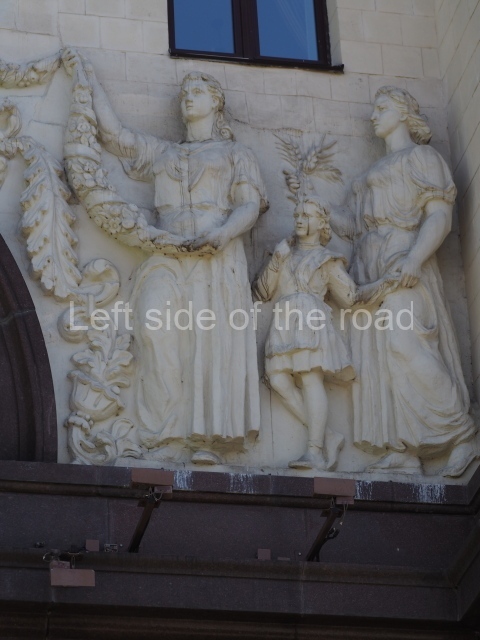

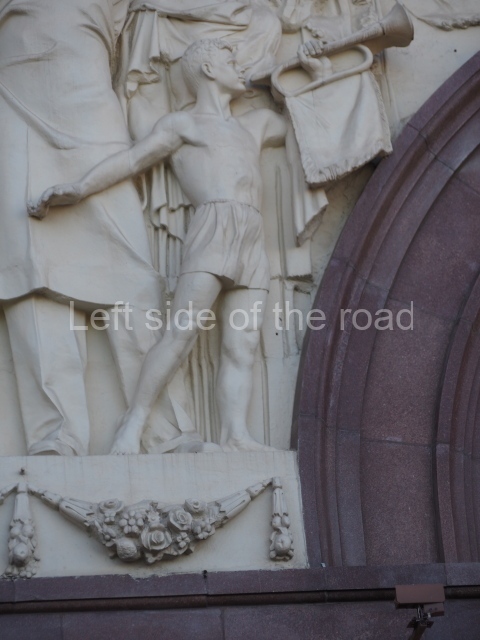

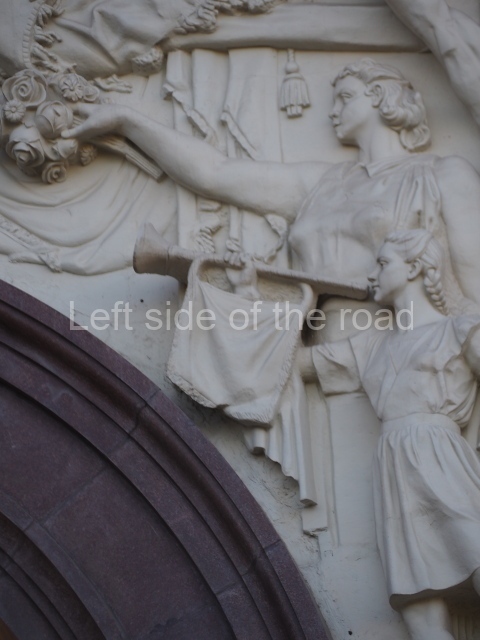

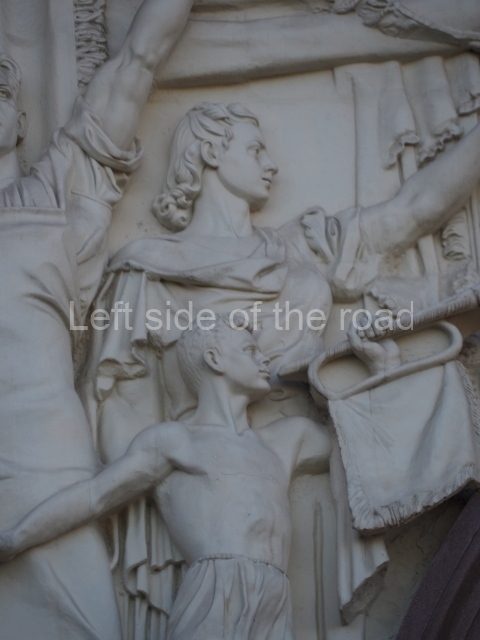

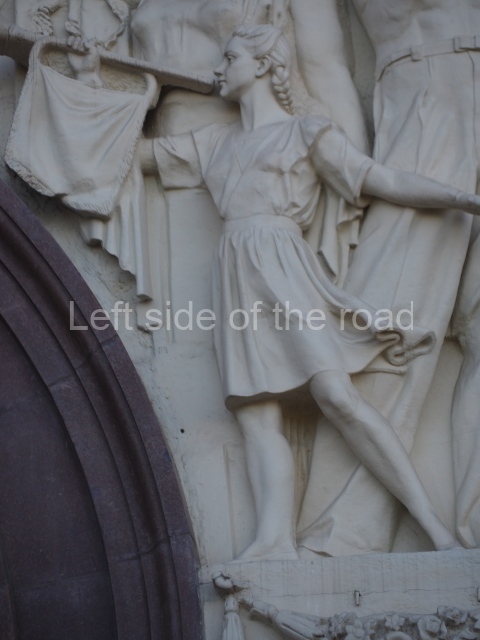

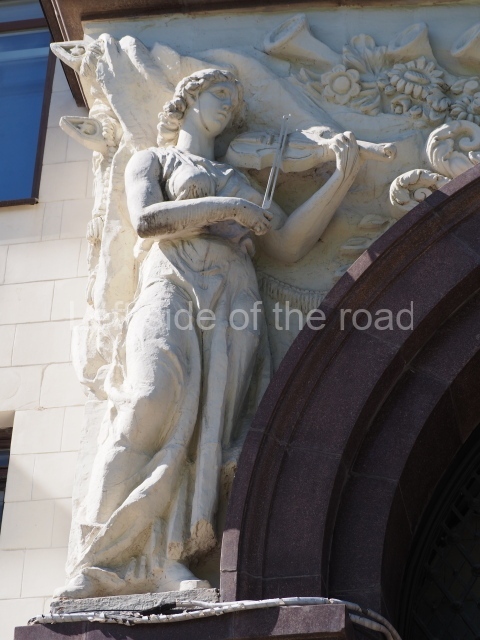

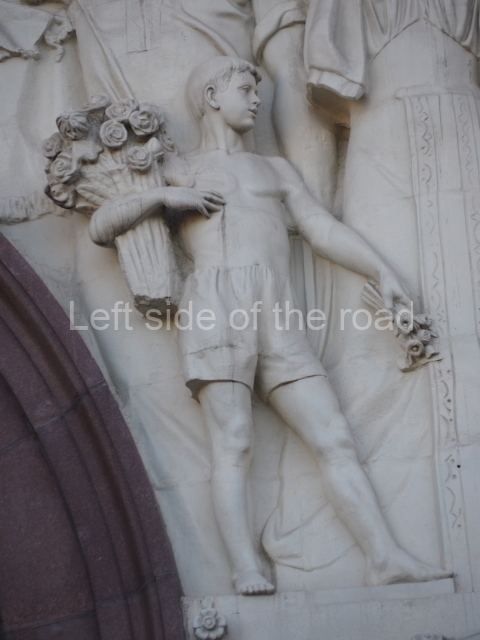

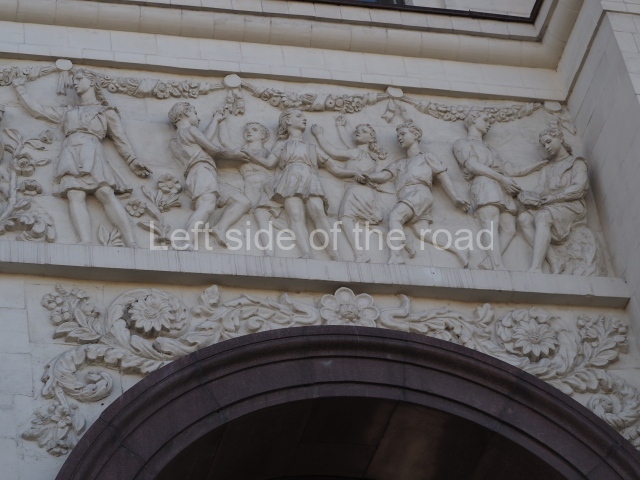

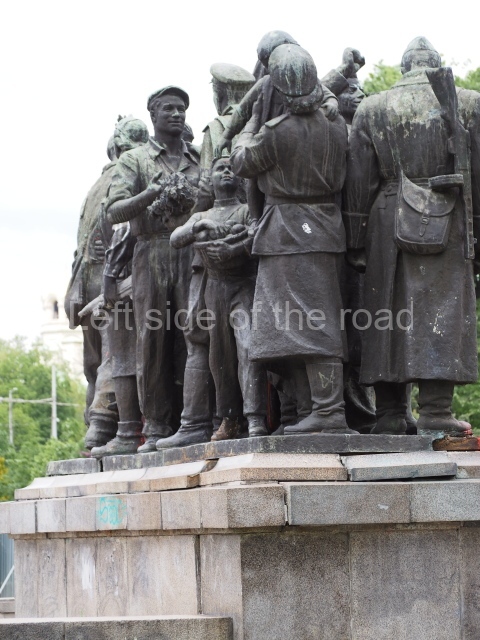

The principal entrance is the stepped route to the pedestal which is flanked by two, low level group sculptures. Both these groups represent Red Army men and women being welcomed by the local populace. They bring food and drink for the tired soldiers and the appreciation of their efforts are being demonstrated by Bulgarians of all ages. There’s a feeling of joy and celebration as the people are freed from the dominance of the invading Nazis and the possibility of being able to build a new future.

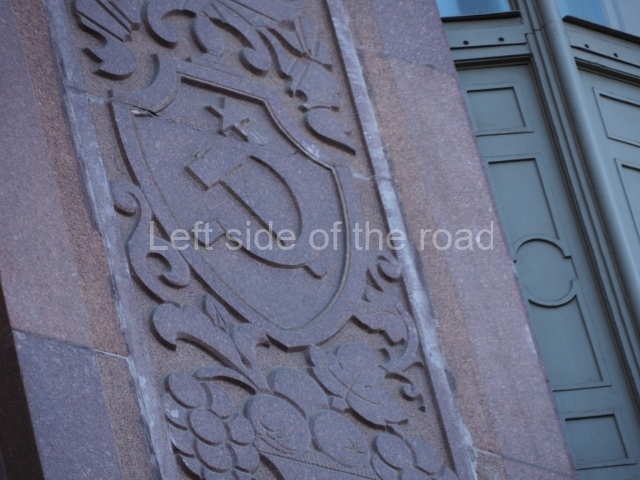

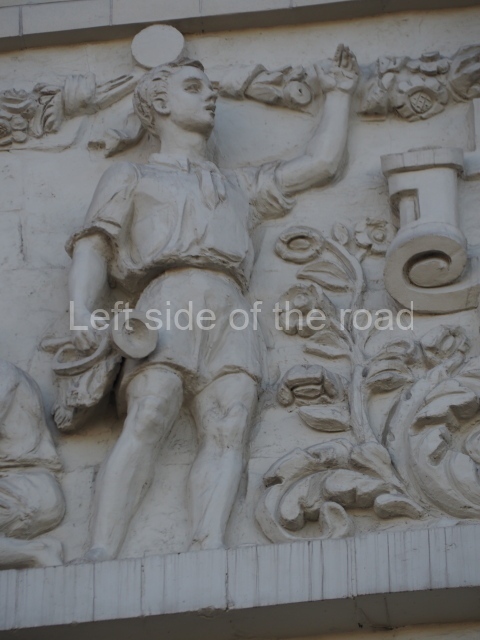

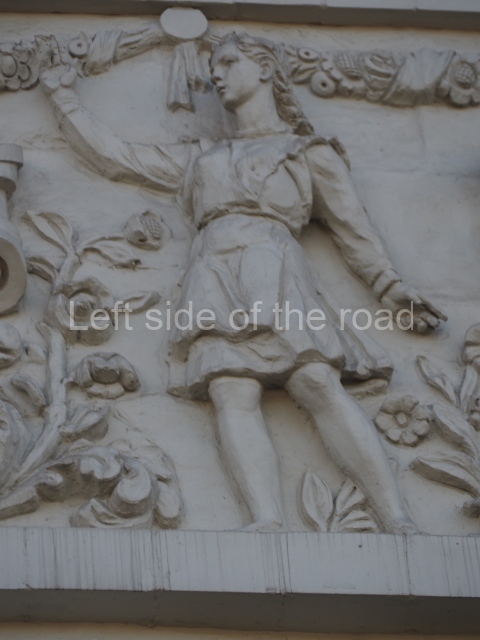

On the sides of the platform on which the pedestal stands are three, large bas relief panels. The ones on the right and left depict war scenes from battles that would have proceeded the liberation of Bulgaria as the Red Army swept west to eventually crush the Nazi beast in its lair in Berlin the following year. The third panel, on the south side, depicts the Soviet ‘home front’ where those not in the actual fighting were making the success of the Red Army possible by their work in the factories and the fields.

All these five sculptural elements have suffered quite severe vandalism, mainly by paint, but there doesn’t seem to be any serious physical damage. At least nothing that couldn’t be rectified with careful cleaning and restoration. Whether that will be their fate or not is unknown.

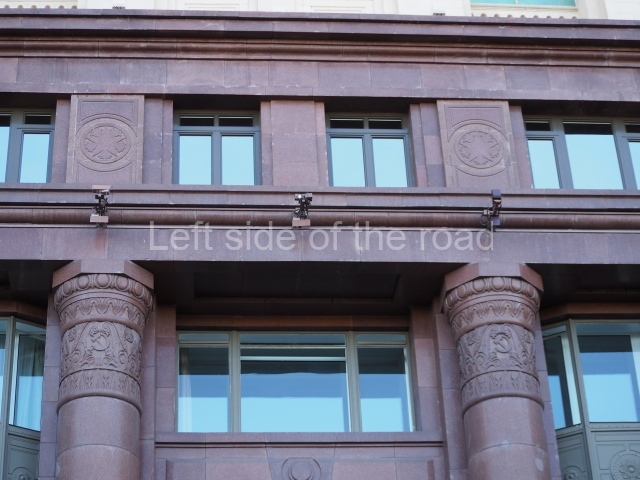

Although the sculpture on the pedestal might have been recently removed access to the complex is still restricted. A 2 metre high metal fence surrounds every single element of the monument, the sculptures as well as the approach steps and platforms.

Obviously there have been efforts, some at least successful, to breach this barrier in the past but equally serious efforts have been made to repair those breaches. I walked around the whole perimeter and was unable to find any way to get inside the fence. For that reason the photographic record is not dependent upon what I would have liked to have presented rather it what was possible through gaps in the fence or standing on benches at one the edge of the barrier.

The fact that the final fate of this monument has been under discussion for 30 years indicates the uncertainty that the reactionaries in power in Bulgaria feel about the public memory of the liberation from Fascism and the role the Red Army played in that. Removing the principal trio with the ‘promise’ they would be relocated to the Museum of Socialist Art is only part of the ‘solution’. Those sculptural elements that remain are larger and more difficult to place outside of their present, and original, context.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any information about those artists and architects who were involved in the creation and installation of the monument.

How to get there:

Leave the underpass of the Sofia University Metro station by the south east exit and walk along the south side of Tsar Osvoboditel Boulevard. After about 200 metres the area of the complex is unmistakeable on the right. In April 2024 the pedestal was still surrounded by scaffolding but the shiny metal fence stands out like a sore thumb.

Location:

In the park, on the south side of Tsar Osvoboditel Boulevard, close to the Sofia University Metro station.

GPS:

2°41′26″N

23°20′4″E