Traditional Wedding – Peshkopia

Traditional Wedding Mural in Peshkopia

There’s a perception by some (normally the ignorant and anti-socialist) that any work of art created during the construction of Socialism is necessarily ‘Socialist Realist’ art. They don’t understand, or refuse to accept, that the construction of Socialism is a long task. When it comes to art this involves asking the people to challenge their view of what is going around them and to look at artistic works in a critical and thoughtful manner and that this involves the unmasking of the hidden messages in a painting, sculpture, film or any other creative endeavour. One such work that needs to be seen in this light is the Wedding Mural which covers one of the walls of the Korabi restaurant in the hotel of that name in the town of Peshkopia.

A bowl of flowers don’t become ‘socialist’ just because they appear in a painting made by an artist who lives in a society attempting to construct socialism. However, as in all periods, those flowers could have another meaning if placed in the context of a particular occasion. It’s also true that works of art created under socialism can contain reactionary ideas which might have been placed their consciously by the artist, as an attack upon the socialist ethic, or subconsciously as the artists has not considered thoroughly the images created. This is why in all ‘Cultural Revolutions’, whether they were in the erstwhile Soviet Union, the People’s Republic of China or the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, what was created was constantly under review and subject to criticism concerning the message such works were giving out.

But the bourgeoisie don’t like the idea that such criticism should come from the mass of the people. They understand very well that certain works of art contain a political message but they want that analysis to be the domain of ‘specialists’, academically trained professionals who ‘criticise’ to more show off their ‘expertise’ than to seek to change the direction in which such works are heading. They want to perpetuate the myth of ‘art for art’s sake’ as this suits very well the capitalist system – it can even tolerate deviations as proof of their magnanimity, but only as long as it doesn’t get taken up as a political force. They want to maintain the myth that artists should be allowed to do whatever they wish as this perpetuates the idea of the individual as opposed to the collective and that the artist has no responsibility to the rest of society.

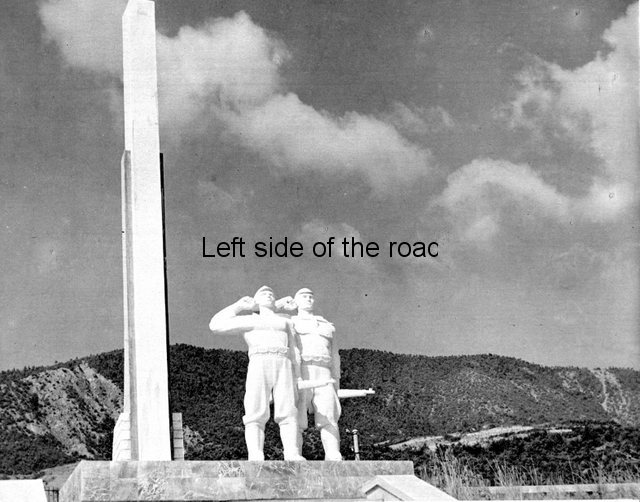

Albania’s Cultural Revolution was running out of steam by the mid 1980s. It had seen a burst of creativity in the various arts, seen most obviously to this day in the lapidars (the public monuments) that exist in all parts of the country, and in a film industry that was producing more films per head of population than probably any other country in the world. Enver Hoxha died in 1985 and the country lost the leadership that had a clear idea of what the building of socialism was all about and which had the ideological clarity to push this forward. (One issue that Communists have to understand, and for which they need to find an answer, is the problem that the movement in a country can be thrown into crisis with the death of a particular leader, sometimes having world-changing effects.) Art during the last five years of the socialist ‘experiment’ in Albania was returning to something that was more individual and which was less and less a tool of the working class for the construction of socialism.

The Wedding Mural, painted by J Droboniku was painted in 1986 in the restaurant of what was, at the time, the town of Peshkopia’s state-run tourist hotel. It’s a strange choice of topic for such a large work in a location where it would have been seen by many people on a daily basis. State run hotels weren’t luxurious places but were cheap and accessible for people who might have wanted to get into the fresh, cool air of the mountains and this would have included members of the Party of Labour of Albania. That being the case I don’t know why this painting wasn’t the subject of criticism at the time.

The painting depicts the arrival of the bride’s wedding party at the home of her husband-to-be in the 20s or 30s of the twentieth century. There’s nothing wrong with a work of art which takes as its subject events from the past, when the society was very different from what it had become in 1986, but as a commission for a state-run enterprise why this particular scene? And if an artist decides to depict the past it is incumbent upon her/him to make a comment about that past which is relevant to the present. There is a continuity from the past to the future but that’s all dependent upon how that past is seen in the present. I can see nothing that approaches that idea in this mural.

The mural is almost divided into two halves, but not quite, the home of the bridegroom being represented by a greater amount of people and activity, as well as symbols of wealth.

Bride-to-be on white stallion

On the left hand side we have the bride’s party arriving prior to the wedding. This is obviously a young woman from a wealthy family. She is very well attired in intricately embroidered traditional dress, hers and the clothing of many of her party giving the impression that this family is not short of a few bob. She is also riding a fine-looking white horse, not a working horse but some prize-winning stallion. As well as that three others of her party, all men, are also riding horses.

Albania wasn’t a rich country before the defeat of the fascist invaders in 1944 but there would have been, as is still the case today in countries where the majority of people live in abject poverty, some who lived very well, basically from the stolen labour of others. So what we are being presented with here is a celebration of a rich woman’s wedding.

I know that weddings are those strange affairs where families can get into serious debt as they want to impress both the family they are marrying into as well as the general population amongst whom they live, fellow landowners and village members. But there’s no indication of that ‘renting’ here. What we are shown we have to take at face value.

The rich are only rich because the poor are poor. In modern society there is a group of people, those who are dubbed ‘celebrities’ who can make a lot of money from sport, from writing, from acting in the cinema but they are only a small proportion of the world’s wealthy. The people who control the 99% of the world’s wealth do so because they have stolen the labour from 99% of the world’s population.

So what we have here is a picture depicting the rich in a society that is seeking to eliminate such differences between people based upon the wealth they hold, not being critical about those differences when they are shown a number of times in the painting itself – and this is all justified by the fact that this is a painting showing events of the past and under the guise of celebrating ‘tradition’ a reactionary story is being propagated. Those things of the past don’t need to be ditched per se but if they are to be kept in a new society they have to be analysed to see what benefit, if any, such ideas have for the future.

Such an approach to the past is not the invention of socialism. All previous social systems have done the same with what they have inherited. It is only by taking what is useful, transforming it for the new social conditions that society moves forward at all. Not doing so would lead to torpor, stagnation and a moribund society that would eventually collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. This is the fate of capitalism – though it has seen itself particularly resilient despite all its shortcomings and failure to live up to its promises in crisis after crisis and war after war.

As well as the class divide shown in this mural (which I’ll come back to) it is in his depiction of women that Droboniku really shows his reactionary credentials.

The young bride-to-be is dressed in fine clothes, sits upon a fine horse and is being fêted, in this scene literally being placed on a pedestal, but only for this moment. She is also being passed from the ownership of one male to that of another. Her father holds the reign of her horse (she can’t even arrive at her own wedding without the involvement of her father), he is shaking hands with the bridegroom and in that single act is passing ownership across from one generation to another. All he has to do is to pass the reigns to the young man, unclasp his hand and then the transfer has taken place without any break in continuity.

The Hand Over of the Bride

And she is playing her expected to role. Her future is being decided at this moment and she isn’t even looking at what is happening in front of her eyes. She merely plays a silent, non-participatory role. She is the object that is being exchanged and she isn’t expected to play an active part in something that was decided some time before and to which she only has to accede, either willingly or unwillingly. She is demure with her eyes downcast, what will happen will happen. This is what a ‘traditional’ Albanian wedding would have entailed.

The bride plays her role and so do many other women in the painting. From the bridegroom’s household we have three women rushing with trays of treats for the arriving guests. Two of them are carrying trays of small glasses of raki whilst the other has a pile of what in Britain is called ‘Turkish Delight’ in Albania is called ‘lokum’. The first is offered whenever a (male) guest arrives at a house, the second at times of an engagement or wedding to everyone. Both these traditions remaining to this day.

Now whether these are family members or servants it’s not possible to say exactly, although at that time a house of this size would almost certainly have had servants. Only one of them, the older of the three, is what you would say ‘dressed up’ for a wedding. Not only is she wearing intricately embroidered clothing she also sports a fair amount of jewellery. This could possibly be the groom’s mother as it would make sense that she would be part of the formal welcoming ceremony.

The groom’s mother with raki

However my point here is that it is the women who are running around serving the guests. It’s not even a significant point that this is what very much happens in present day Albania. On arrival at a house guests will be given something but it is almost invariably the task of the women to do this, the most the men do is to pour the raki (often). Why this matter becomes significant when discussing a painting created under the system of socialism is that, specifically during Albania’s cultural revolution, the stress was on depicting women in such a way as to get away from what was the traditional. By showing the women thus Droboniku perpetuates the stereotypes.

The Proposal?

Other women play similar ‘traditional’ roles. Under the stairs there is a young couple, she with a small bunch of flowers in her hand and her head coyly inclined slightly to her right, towards her partner, there’s even an indication of a blush. Has she just been proposed to, he taking the opportunity of the nuptials to pop the question? Neither of them is richly dressed so they wouldn’t be under the same restrictions about who to marry as would the daughters of the house.

Young women dreaming of their day in the limelight

In and around the house other younger, single girls look wistfully on the scene unfolding below them as if they are wondering when they might be the centre of attention on their wedding day. Here we have the suggestion that young women only wait for the day when Prince Charming will come and whisk them away to a happier life. Again Droboniku perpetuating stereotypes.

The argument that the painter might make that this is a picture of what ‘was’ the situation wouldn’t hold water as here is no indication that this attitude of the past is being criticised or challenged in any way.

In other images it is the boys and the men who are the ones play-acting, dancing, making noise and music. The girls and the women either look on quietly and demurely, hold bunches of flowers to give to the arriving guests or serve.

Male dancers and musicians

Three of the men are shown armed, two of them firing into the air. Although in many ways women with guns firing at a traditional wedding would have been unlikely there is still a point to be made about women being armed in Albanian Socialist Realist art and how things seemed to change towards the latter works and that was the pictorial disarming of the women. Take their guns away that they had used so effectively during the National Liberation War and force them back into the roles they played before the war – roles of subservience and domesticity.

(This idea of women not being suitable for the carrying arms is one that exists throughout the world. The debate about the right to bear arms has been going on in the US for decades – and probably for decades to come if there’s no radical change in that society. Even there an armed woman is seen as threat. In the most recent version of the western ‘The Magnificent Seven’ (2016) there’s an incident almost at the end where the only women depicted as taking up arms and fighting against the bandits has her rifle taken out of her hands, by the person whose life she has just saved. This wordless gesture says a lot about society at the end of the 19th century as well as today. The crisis is over, now just go back and be a housewife, dirt farmer, or whatever she was before. Such tasks don’t need the woman to be armed.)

Whatever gains women made in the years between 1944 and 1990 in achieving ‘equality’ in society have been attacked and undermined. Notwithstanding that there might be women in positions of power within the political establishment this is not reflected in the majority of homes or even in public. Young women in Tirana might have the seeming freedom to do what they like (with many caveats) but this disappears in the rest of the country. As an example, in August this year I walked through the new part of Gjirokaster late at night. There were many males in the numerous bars I passed but I didn’t see one woman, as a customer or working.

Young woman with good luck charm?

There’s only one saving grace in this matter in the picture and that’s the young woman, dressed in more contemporary clothing who is a member of the bride’s visiting party. She’s running forward, her left arm raised in the air and what appears to be a yellow butterfly resting on the palm of her hand. I didn’t notice this when I was taking my photos and so don’t have a really good close up of the hand to determine exactly what’s there. I’ve also been unable to find any explanation for such a possible tradition at a wedding. Is it a sign of good luck? I don’t know.

It would be going to far to say she plays a revolutionary or progressive role but at least she’s doing something which doesn’t involve swooning or subservience.

Making noise at the wedding

Does the painting have any merits whatsoever? It’s good at depicting the traditional dress of the time as well as the antics of the musicians add dynamism at the right hand edge of the picture. Here there’s a man firing his pistol in the air so it’s noisy in this area whilst everything is very subdued in the centre and left hand side. (However, there’s another down side in this part of the painting with the very prominent name of the painter on one of the beams of the building.)

Even though not the everyday clothing for the overwhelming majority of the population during the period of socialism everyone would have been familiar with traditional dress, music and dance from all parts of Albania. There would have been countless opportunities to have experienced this during the year, culminating in the National Folklore Festival held in Gjirokaster. This used to take place every five years and involved people from the surrounding countries as well as all parts of Albania. The desire for all things foreign puts this public memory under threat although there are attempts to make Gjirokaster, once again, the centre for the celebration of traditional music and dance.

The mural also includes clues to exactly where the event is taking place, such indicators being seen elsewhere, including the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Durres and the bas-relief in Bajram Curri. The backdrop to the scene is the mountain range above the town of Peshkopia, which includes the Mount Korabi and a vista that would have been very familiar to local people.

Location:

The mural is on the left hand side wall as you enter the restaurant from the main street. The hotel is just across the road from what used to be the headquarters of the Party in Peskopia.

Lat/Long

N 41.68585

E 20.42689

DMS:

41° 41′ 9.06” N

20° 25′ 36.804” E