Tenam Puente – Chiapas

Location

From the point of view of its physical geography, the Comitan Plateau situated in the eastern Chiapas Highlands presents groups of moderately high elevations ranging between 1,600 and 2,000 m above sea level; the climate is mild, with an average annual temperature of 24° C and a rainy period between June and October. The vegetation, nowadays greatly transformed, comprises some of the original pine forests and different varieties of oaks or holm oaks. There are also large quantities of bromelias and orchids, which are used as offerings in the various traditional religious processions held in the region. Due to the local karst characteristics, defined by permeable limestone soils, large masses of water are very infrequent; the Rio Grande is the only river that crosses the Comitan Valley and flows into the Montebello Lakes. For the ancient Maya groups who populated the highlands, the physical geography played a key role in the location and construction of their ceremonial centres. Elements such as caves, springs, cenotes and mountains were regarded as holy places, manifestations not only of the sacred but also of earthly power. Proof of this is the diversity of constructions to be found at the numerous pre-Hispanic settlements on the hilltops surrounding the Comitan Plateau, including the site known as Tenam Puente. The word Tenam is derived from the Nahuatl tenamitl, meaning ‘fortified place’. The second name is a reference to the old ‘El Puente’ (‘Bridge’) estate that once existed on what is now the heart of the cooperative in the village of Francisco Sarabia. According to the Danish explorer Frans Blom, the name Tenam was habitually used in the region to refer to the groups of hilltop mounds. The turn-off for the site is situated 10 km south of Comitan, on the Pan-American Highway.

Pre-Hispanic history

This site was one of the most important polities in the eastern Chiapas Highlands, occupying a prominent place in the ritual landscape not only during pre-Hispanic times but nowadays as well. The Acropolis was conceived as a sacred space with clearly defined circulation areas. We now know that this was the result of successive construction phases consisting in the modification and levelling of the hill through terraces excavated at different heights. The presence of three ball courts denotes the importance of the site within the region; to date, no other site with so many ball courts has been found either in the Comitan Valley or in the neighbouring areas. Situated in a mountain range separating the warm land from the cold land, Tenam Puente must have participated in the trade networks between the two regions.

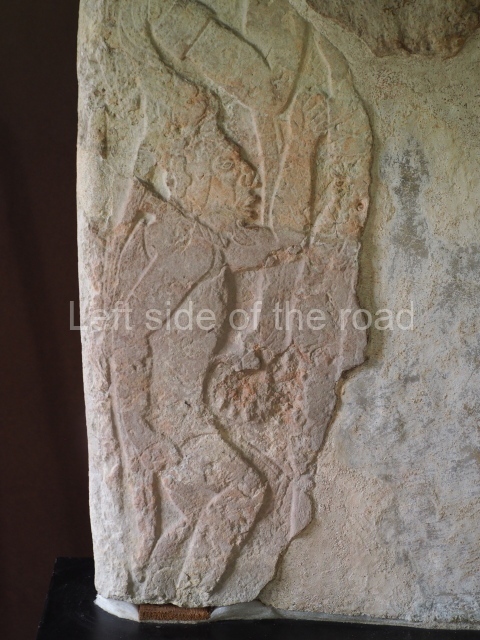

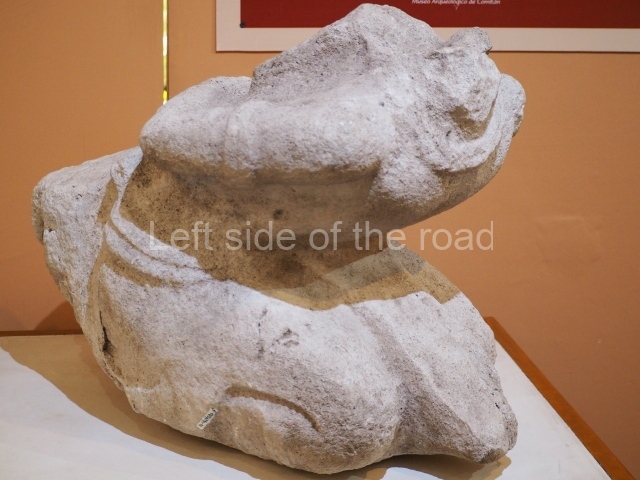

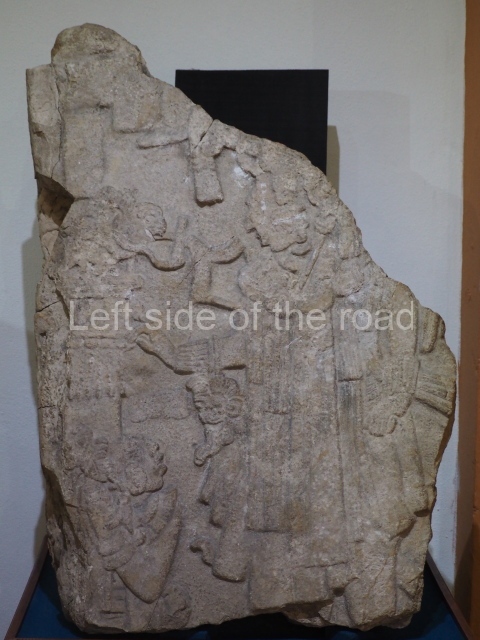

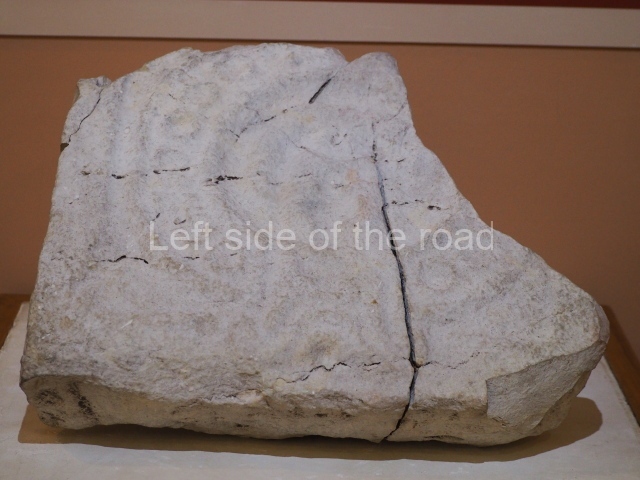

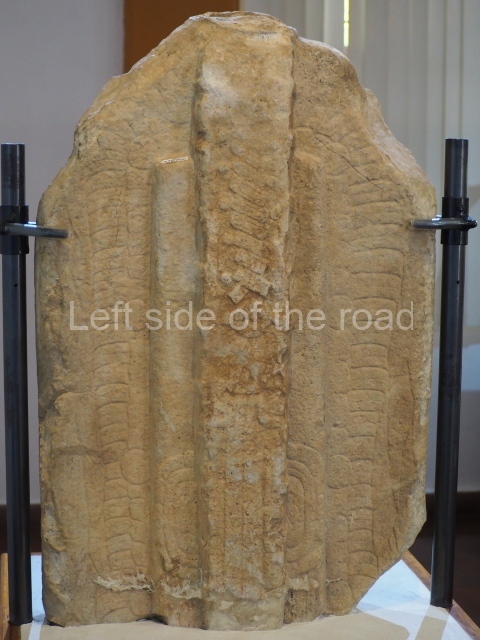

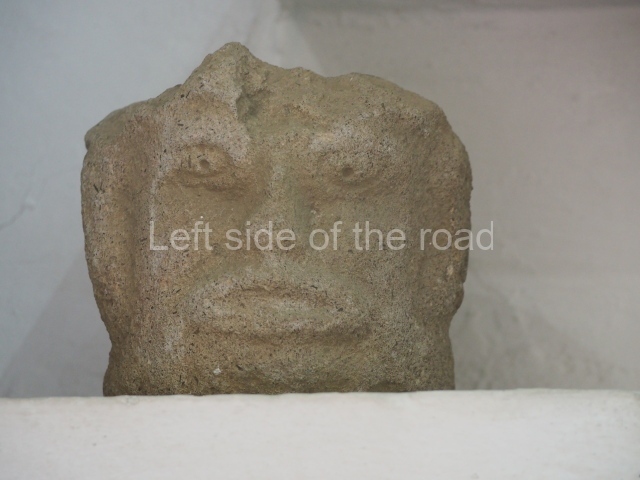

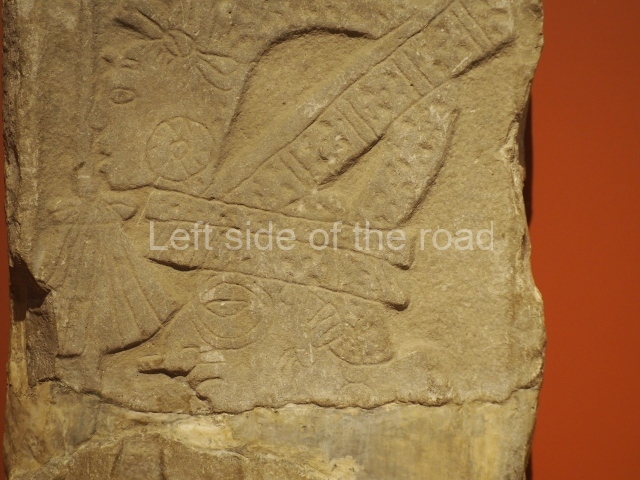

Despite the ceramic remains from the Late Preclassic found in the eastern and uppermost section of the Acropolis, the architectural expansion of the site commenced in the Early Classic, when the western section of the Acropolis was defined. When the majority of the sites in the lowlands had been abandoned at the end of the Late Classic, Tenam Puente and other nearby sites such as Hunchavin, Chinkultic, Tenam Rosario and Santa Elena Poco Uinic continued to be occupied. The tradition of erecting stelae was a relatively late arrival in the Comitan Valley. The only complete monument that has survived to this day is currently on display at the Regional Museum of Tuxtla Gutierrez. Due to its stylistic similarities with the stelae in the Usumacinta region, Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge attributed the date of this monument to 9.18.0.0.0 in the Maya Long Count (AD 790). The presence of cultural traits from the Maya lowlands suggests a vast migration to the plateau at the end of the Late Classic. Other fragments of stelae depict a warrior with a spear grasping a prisoner by the hair.

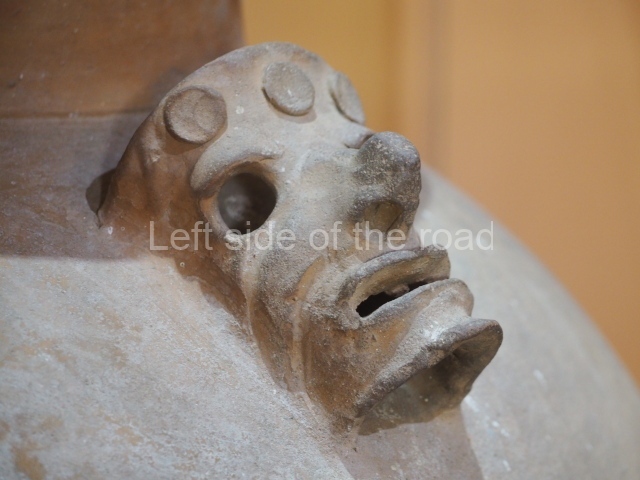

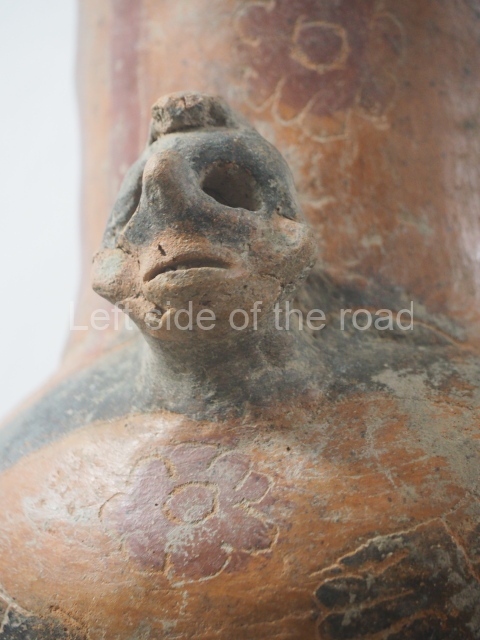

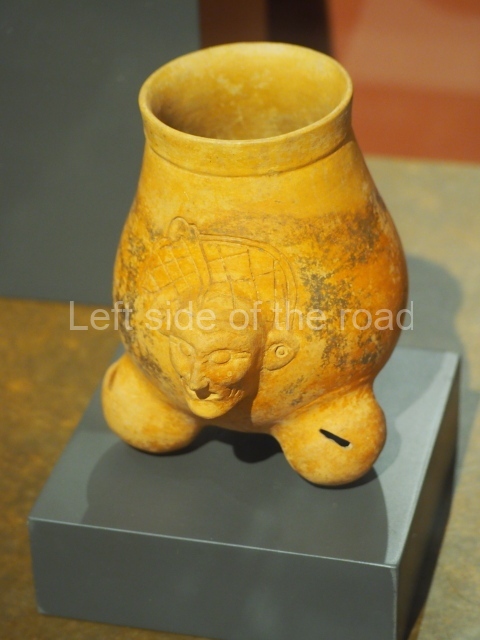

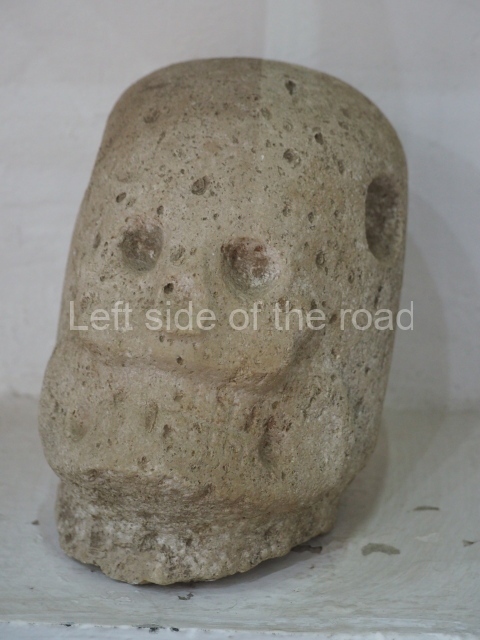

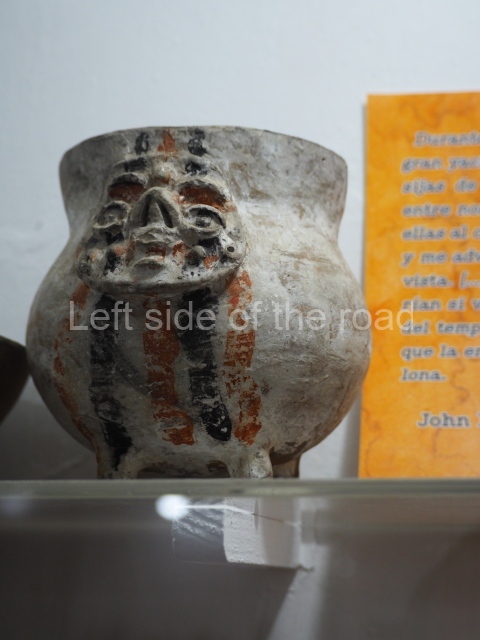

At the end of the Late Classic, several events occurred and appear to have given rise to new funerary customs. The rectangular cists used for burials were looted and, occasionally, reused. During this phase, square tombs with seated dignitaries were used as burials, and the ceramics are of the Fine Orange and Plumbate varieties. Some of the sculpted monuments were destroyed and scattered around the Acropolis and inside a few of the temples. Funerary urns containing cremated human bones were introduced for burials, placed either at the foot of temple stairways or as offerings in the buildings at the top of the Acropolis.

Site description

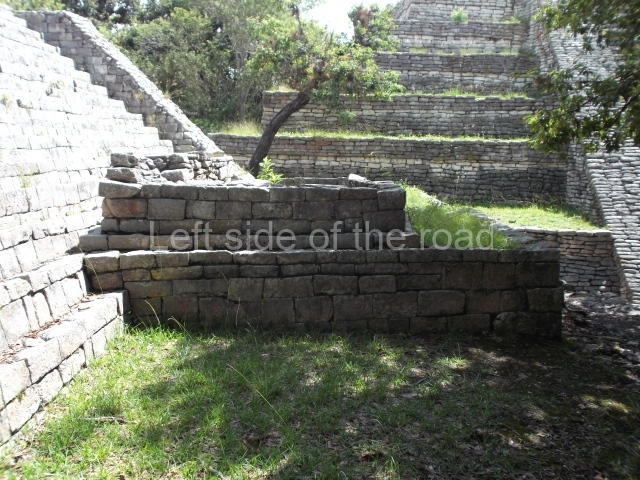

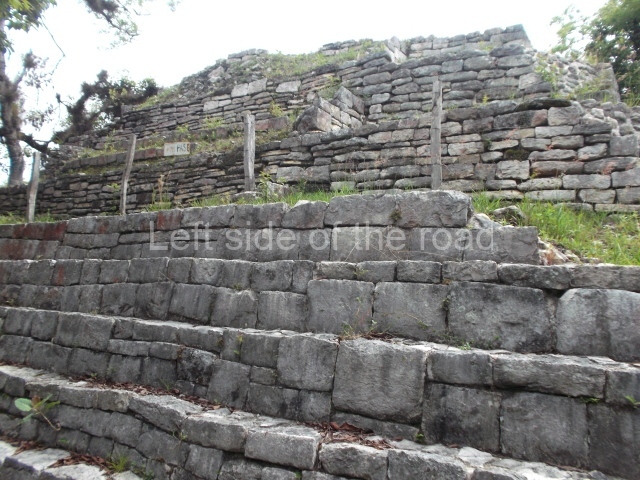

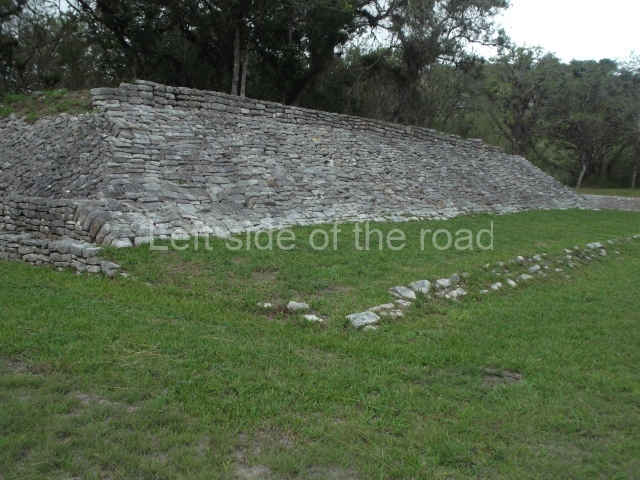

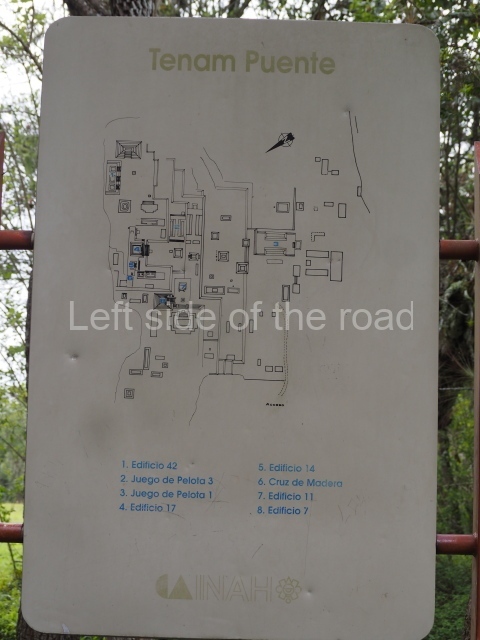

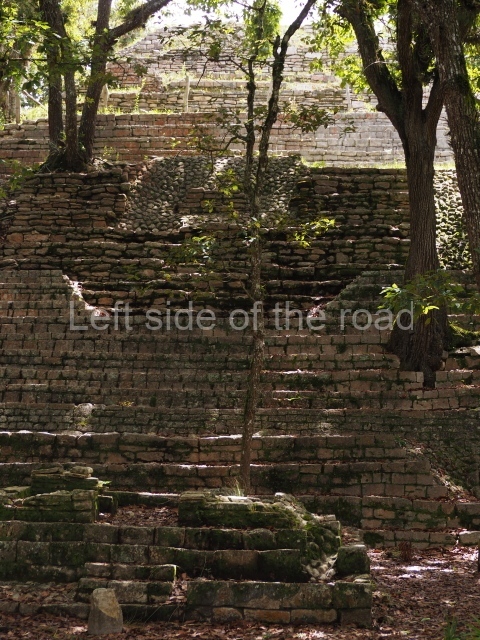

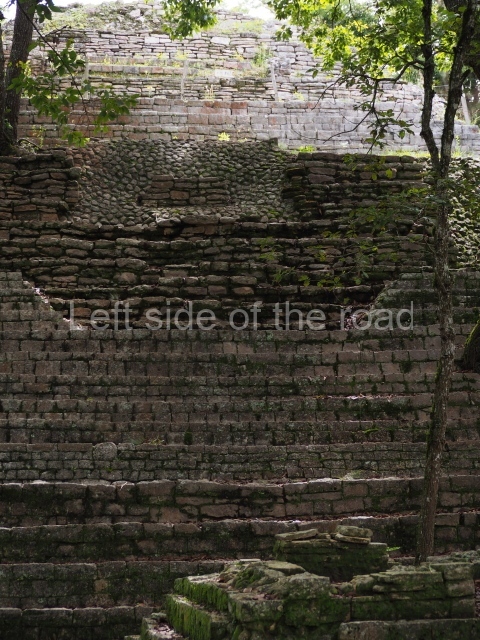

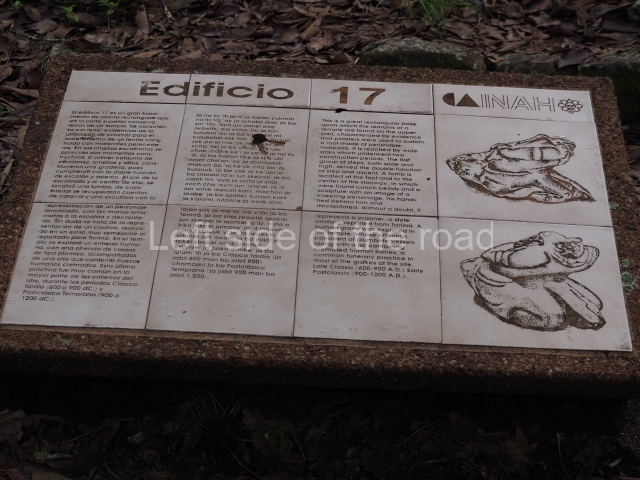

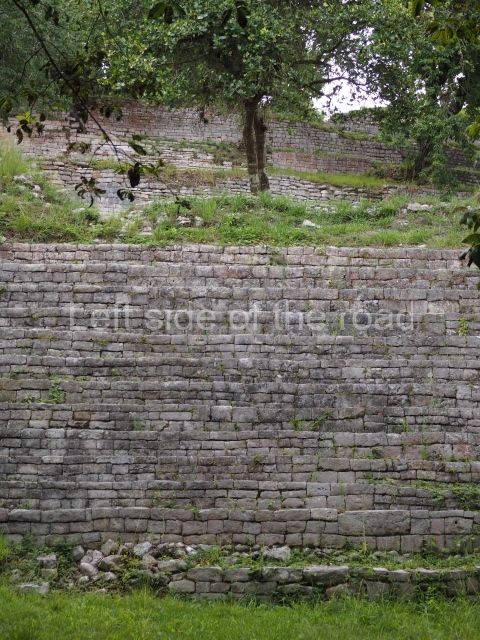

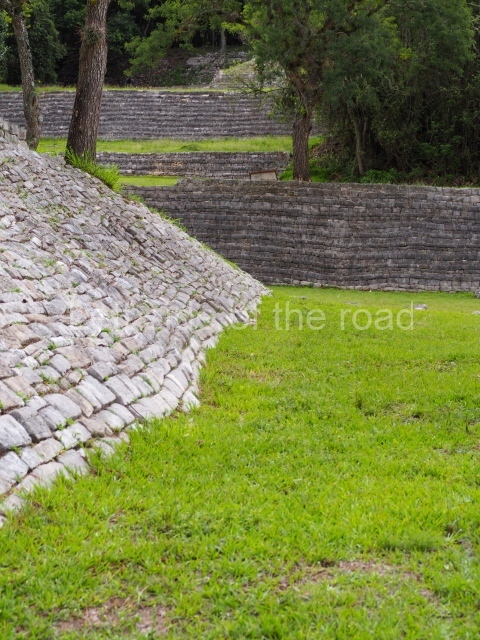

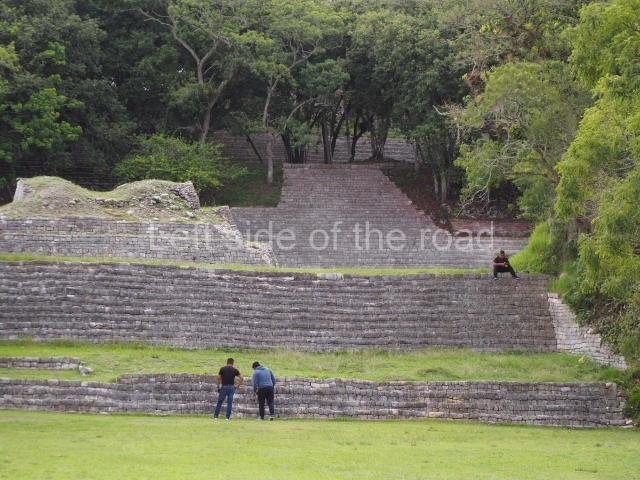

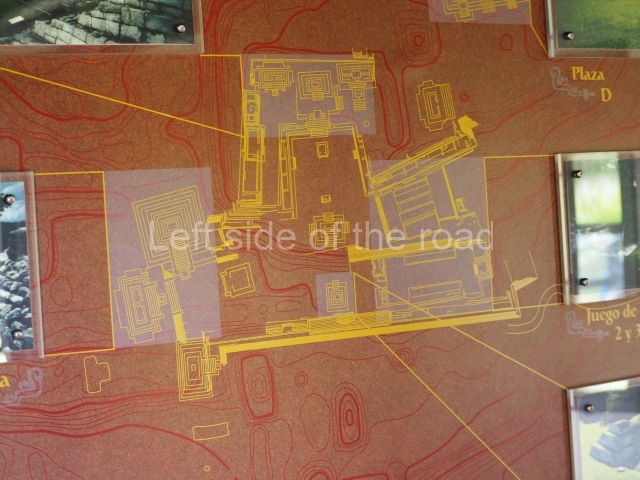

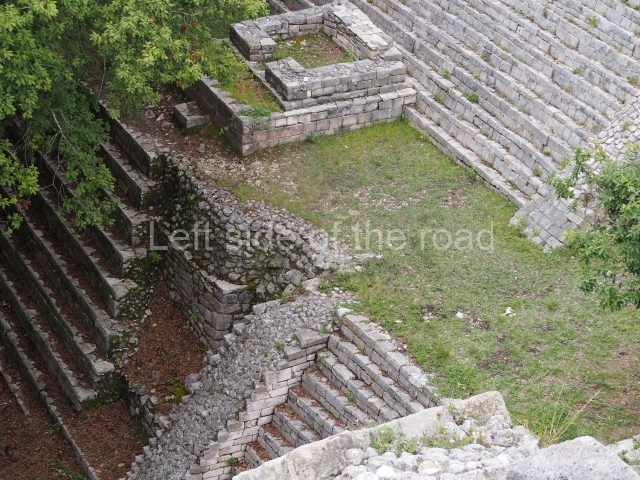

Tenam Puente is an example of architecture integrated with the landscape; the buildings exploited the natural topography of a hill, modified to meet the needs of the ancient settlers. The core area comprises an acropolis situated at varying heights with plazas delimited by temples and platforms for different uses. The residential units are located around the edges, alongside crop fields and probably workshops for making lithic tools; additional temples were built on the adjacent hills. The sacred precinct contained the seat of a political power associated with religious manifestations; its topographical location was clearly strategic, representing the concept of the sacred mountain. The numerous burials recorded suggest the presence of a place where ancestors were worshipped. Buildings 17, 21, 20 and 29 formed a symbolic axis that crosses the Acropolis and divides the sacred precinct into two separate sections. The orientation of the buildings holds great significance and bears an extraordinary similarity to Santa Elena Poco Uinic, a site with very poor access which has not yet been explored. As a result of this division, the ball courts were confined to just one section of the Acropolis. The most outstanding construction on the symbolic axis is building 29, whose main facade must have been covered with modelled stucco depicting representations of Venus and other symbols associated with death and the sun gods. In front of the stairway stood a stela, probably smooth, with traces of reddish paint, suggesting that the text or iconographic motifs were painted rather than carved like the other stelae; stucco modelled masks were habitually buried beneath this stela. Another important construction along this axis is building 21, where the tomb of one of the governors of the site was found. Now sealed, the tomb had masonry walls and a flat mud roof with stucco painted in red and blue. Inside it was a large funerary urn with a rich offering comprising sea shells, the claw of a feline, a large pyrite mirror, numerous green stones and several representations of the quincunce symbol which represents the four cardinal points and the centre of the universe. Fragments of modelled stucco representing reptiles and the bones of the macaw, a bird associated with the celestial sphere, were found on the floor of the south bay. Due to its situation within the Acropolis, this building represents the axis mundi. Both the offerings and the architectural elements suggest the representation of the three planes of the universe: the tomb symbolises the underworld, the building the terrestrial plane and the bay the celestial sphere.

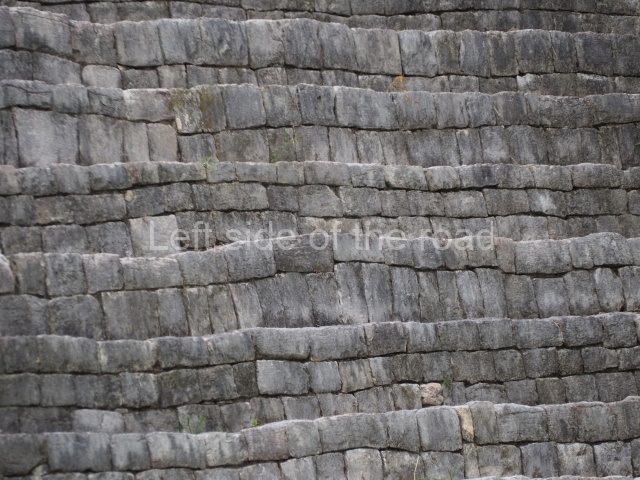

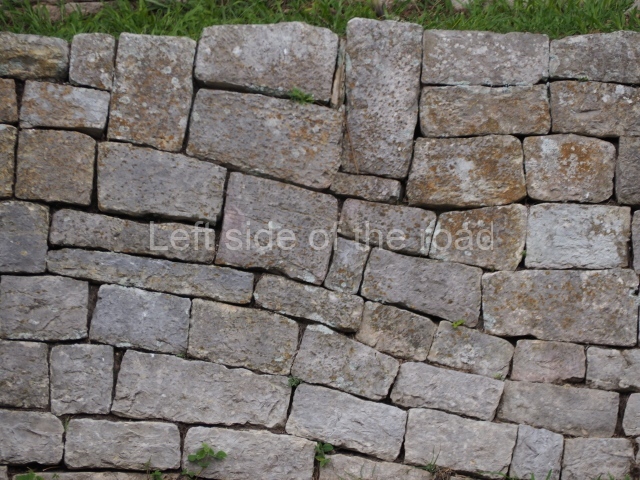

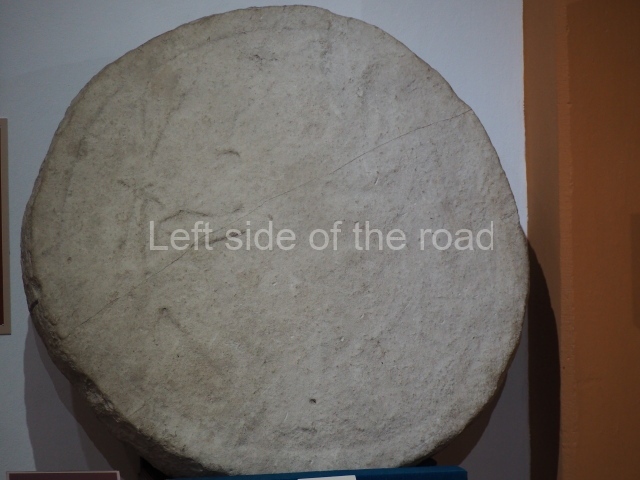

All three ball courts adopt the form of a double T, as well as being sunken and enclosed. The first one is situated in front of the first large terrace, in the lowest part of the Acropolis. Various alignments with slab stones were excavated on the south side, as well as a channel that may have been a steam bath. The ancient inhabitants probably used this court to watch or participate in the ceremonial game, an event that must have been associated with the underworld. The other two ball courts are situated on higher levels, are smaller than the first one and were probably restricted to use by the elite or ruling class. They have furnished several fragments of sculptures of prisoners, very similar to those reported at Tonina. The third court was probably used for settling disputes with neighbouring polities, while the adjacent plaza (Plaza B) must have hosted ceremonies to legitimise the site’s power. The architecture of the site is defined by the regional style that characterised the eastern Chiapas Highlands at the end of the Classic era. This is reflected in the use of masonry, which was initially composed of coarsely cut stones but gradually evolved, as techniques were perfected, to the use of finely cut veneer stones. By the end of the Late Classic, this system was used to clad the majority of the buildings. Stairways divided into two sections were used, recalling the late styles of the Guatemalan Highlands. Floors were made of stucco, sometimes painted red; stucco was also used to cover the treads on the stairways and for modelling different representations of gods and celestial elements to cover the main buildings. There is evidence of the use of drainage systems in some of the Acropolis buildings. Although the Acropolis was abandoned at the end of the Late Classic (c. AD 900), the settlers of the common ground, related to the Tojolabal, maintained the sacred precinct thanks to their devotion and pilgrimage to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in the northern section of the Acropolis (building 14).

Legend has it that the former owners of the ‘El Puente’ estate presented this statue of the Virgin Mary to the townspeople when the common land was created. The festivities are held in the middle of August to request rain and good harvests, which are vital for the community. Next to Building 14, the settlers erected a wooden cross where the statue is placed for the duration of the festivities. An old xhinil or holm oak on the north side of the building forms part of the sacred elements, and the pilgrims walk anti-clockwise around the tree three times after placing the statue next to the cross. However, the inhabitants of Francisco Sarabia are not the only ones who use this space; at different times in the past other communities have visited the site to conduct rituals associated with the so-called Indian theology; both groups coincide in their belief that mountains are important sacred places.

Gabriel Lalo Jacinto

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp461-464

How to get there:

From Comitan. Combis going Sarabia can be flagged down opposite the Centro de Abastos, on the main road through town, the Pan-American. They will take you to the site. Not sure if all combis will go there so you might have a wait coming back. M$15-20 each way.

GPS:

16d 08’ 29” N

92d 06’ 21” W

Entrance:

M$70