Karl Marx Tomb – Highgate Cemetery, London

Karl Marx Tomb and Memorial

The British working class have shown themselves somewhat reluctant to take on board the revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx in the past. This is a shame on a number of levels but especially as he formulated his ideas based upon the what he learnt of how the first real ‘working class’ – in the sense of a class that was totally divorced and separated from the means of production – developed as the industrial towns of England sprung up from the mid-18th century onwards. But as they were so central to the development of his political and economic theories he lived and died in England and the Karl Marx Tomb and Memorial is in Highgate Cemetery, northern London.

Original Location

Karl Marx original tomb – Highgate Cemetery, London

When Marx died on 14th March 1883 he was buried in the family plot which already contained his wife, Jenny, who had died a couple of years before. They weren’t alone for long as within a week of his death Marx was joined by his five year old grandson. The family’s life long friend and companion (who had started out as a servant) Helene Demuth joined them in 1890 – after helping Frederick Engels put together Marx’s notes that became the second volume of Capital – and then the last of the group to use the plot was Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, who died young in 1898.

This unremarkable and nondescript grave, tucked away in the central part of the cemetery, was Marx’s almost final resting place until the 1950s.

The plan for a Memorial

Coincidently or not (I’m not sure) very soon after the death of the great Soviet leader and Marxist-Leninist, JV Stalin, in March 1953, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) made plans for a much more substantial memorial to the founding father of Marxism. An application was made, and permission given, for all the remains in the original location to be disinterred and reburied (in 1954) in a much larger plot close to one of the main pathways through the cemetery.

A commission was then given to a member of the CPGB, Laurence Bradshaw, a sculptor and he designed the plinth (made of marble), the very large bust of Marx (bronze) and also choose the quotes and completed the calligraphy. One thing he did which I very much liked and that was in no place will you see mention the sculptor’s name. This is in line with arguments I have made in relation to art commissioned and carried out under a system where Socialist Realism is in operation, in particular Albanian lapidars, that the artist should step back from the art work and not make it all about themselves. The memorial was unveiled on 15th March 1956 in a ceremony led by Harry Pollitt, at that time the General Secretary of the CPGB.

The Memorial

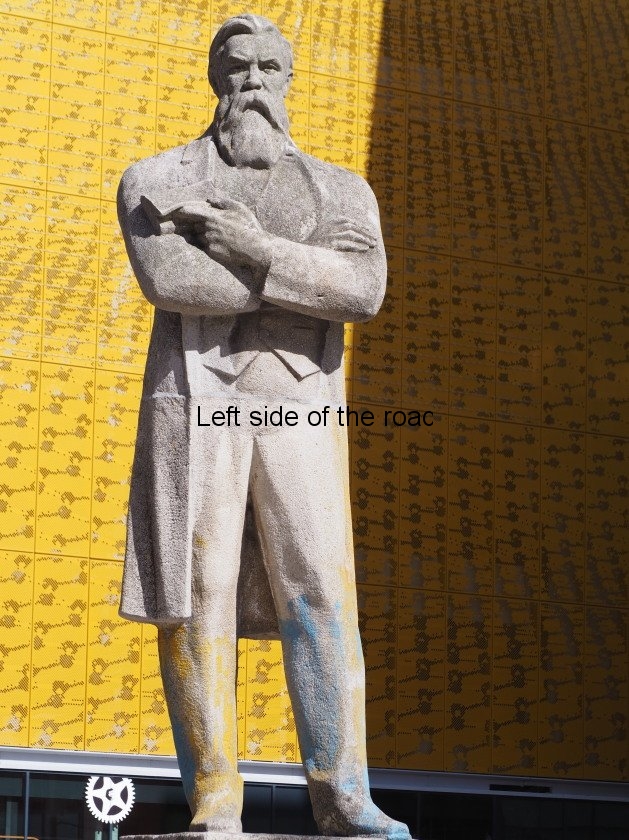

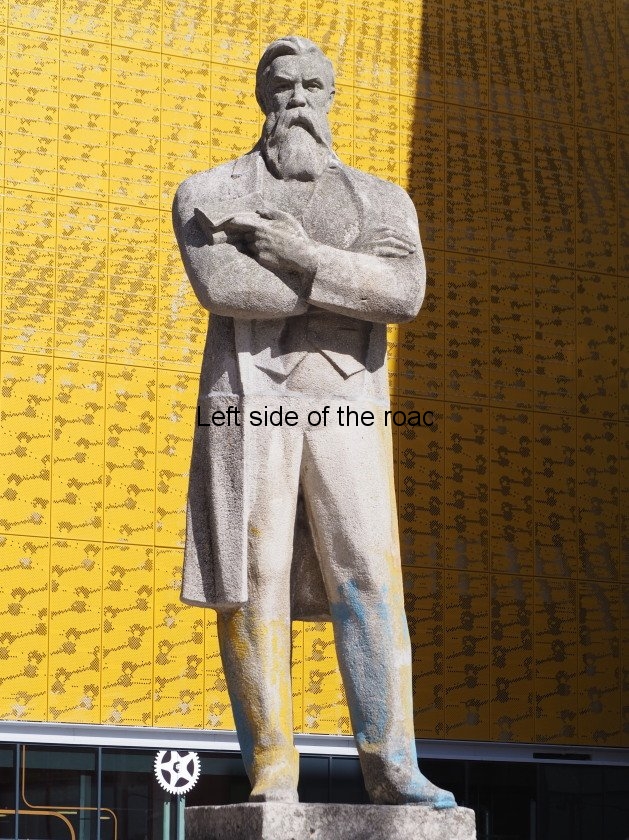

It’s quite a simple, and striking, monument. Whether I like it is another matter.

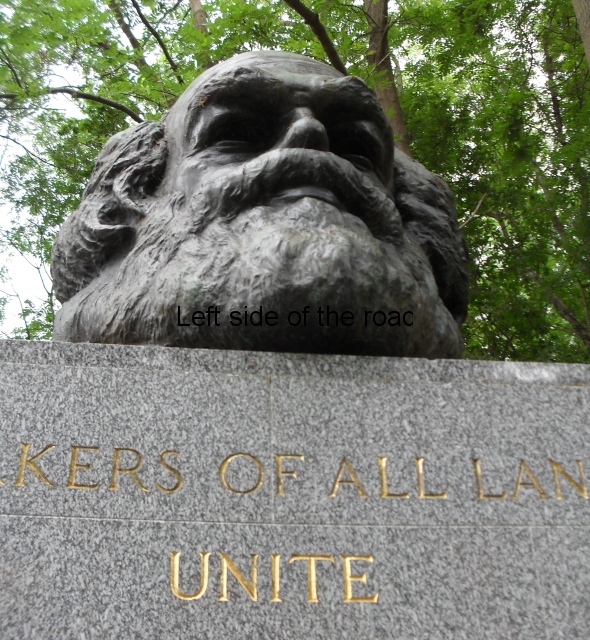

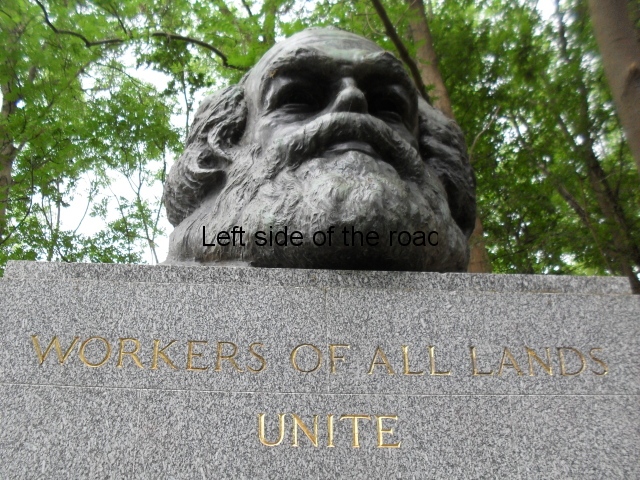

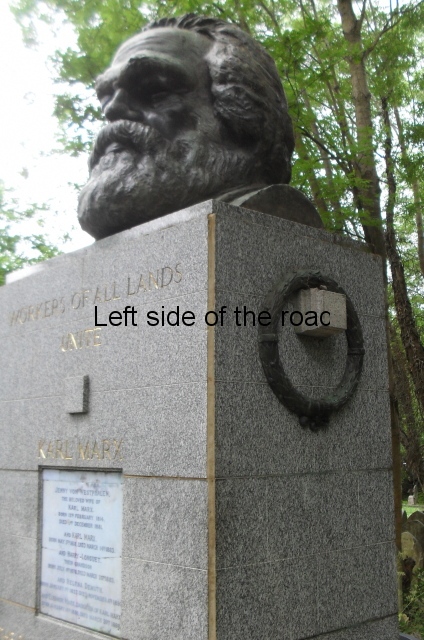

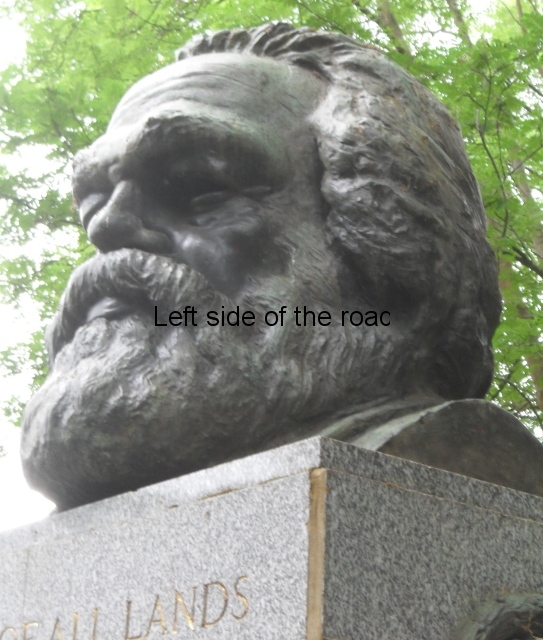

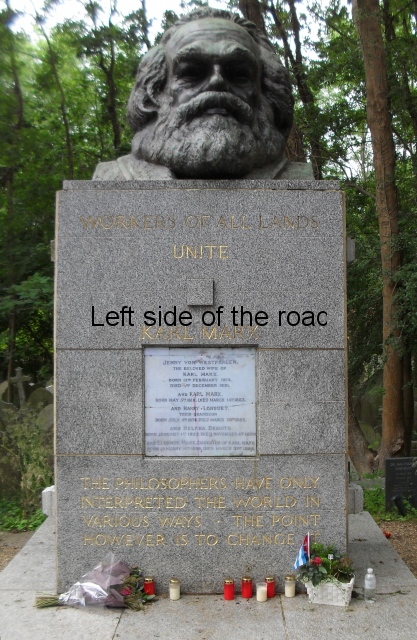

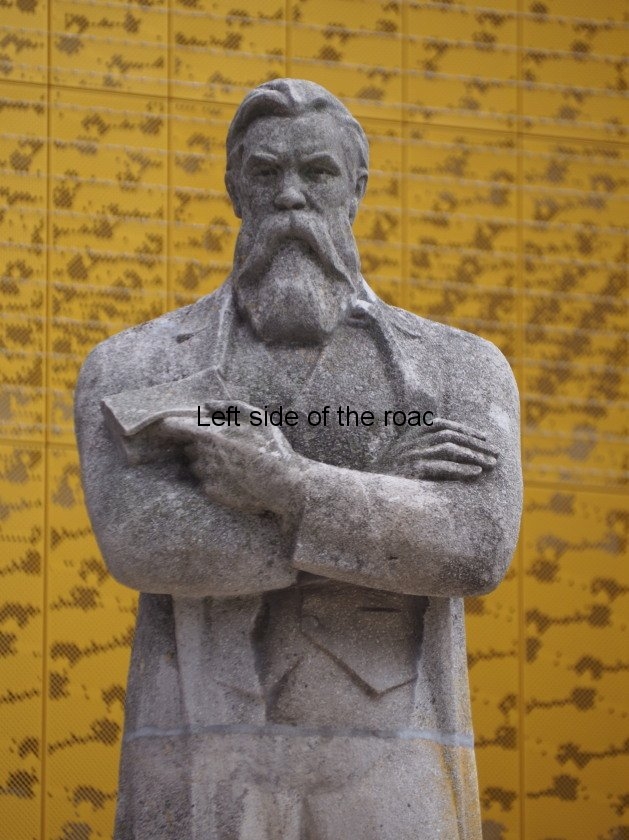

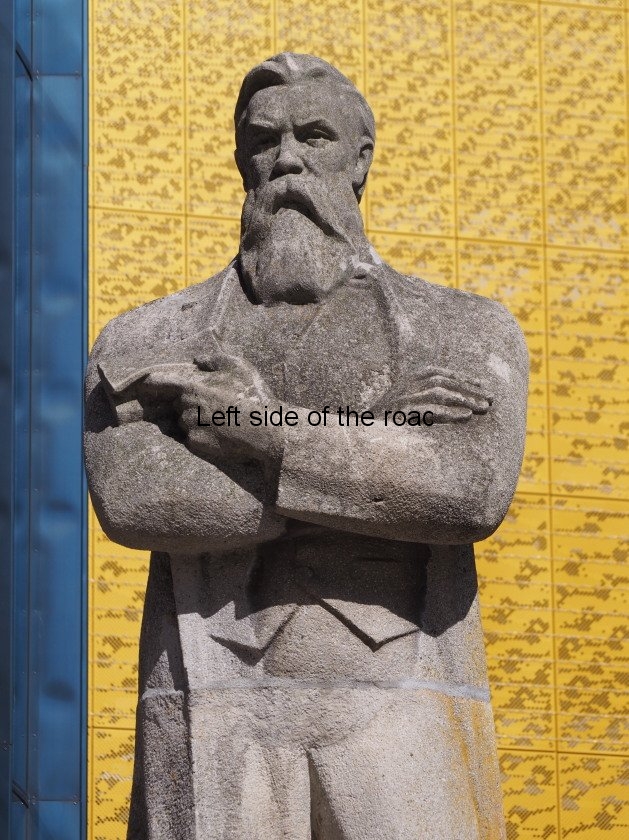

It’s a basic marble clad monolith upon which sits a huge bronze bust of Marx. The plinth is about 3 metres high and the bust must be at least a metre high itself. I think what makes the bust seem slightly strange is that Marx’s beard is virtually touching the edge of the plinth. He looks as if he is crouching down. Perhaps if Bradshaw had given Marx more of his shoulders then it wouldn’t look so pressed down. Apart from that I think it’s a good likeness of the proletarian ideologist.

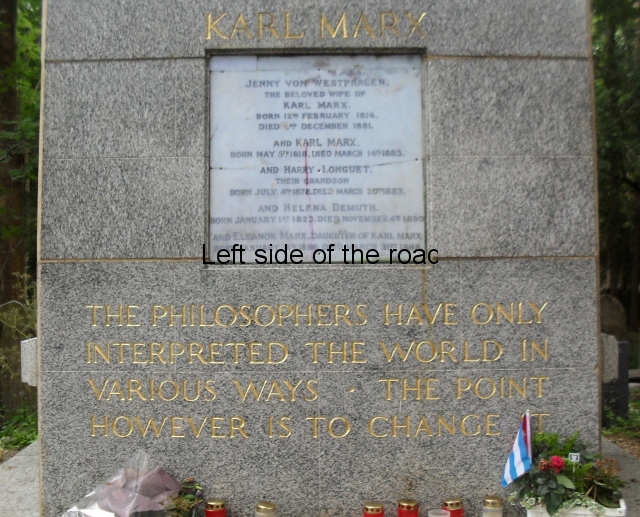

On the front of the plinth, just under the bust, are the words ‘ Workers of all lands unite’, the final word, the most important word in the phrase, being on a separate line underneath, placed exactly in the centre. These words come from the very end of The Manifesto of the Communist Party although in authentic texts they are written as ‘Working men of all countries, Unite!’ The meaning is the same but with a different construction taking into account the way of thinking in the middle of the 19th century. Then just about halfway down, and centred, is the name ‘Karl Marx’.

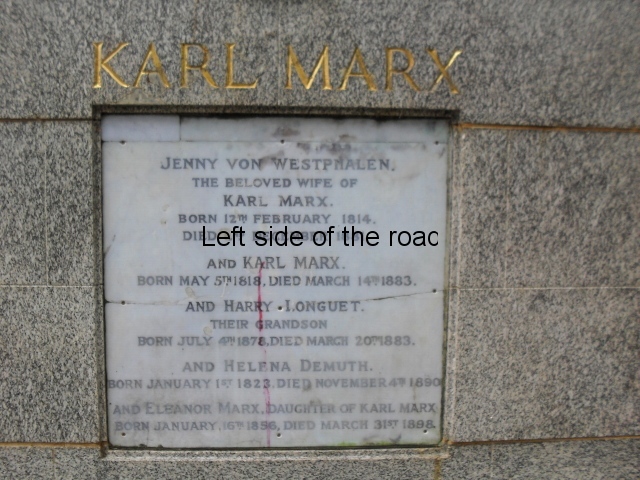

Karl Marx Tomb – central plaque

Beneath his name (also centred and slightly indented) is the white marble plaque placed at the original site of the tomb. Or should I say ‘was’. It was damaged in February 2019 and now there’s a plastic facsimile in its place. Whether the original is underneath or has been taken away – either for conservation or for repair – I wouldn’t know. This is inscribed with the names of the five individuals in the tomb, with there birth and death dates.

On the bottom third, or so, of the plinth are the words ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it’. These are the very final words from the Theses on Feuerbach, (point XI), which was written by Marx in the spring of 1845 – preceding the publication of The Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848). One slight quibble here. In the written text the words ‘interpreted’ and ‘change’ are emphasised. As Marx thought it important to do so in his text it’s a shame that Bradshaw didn’t also include, in some manner, the importance of that stress. All the text is highlighted in gold.

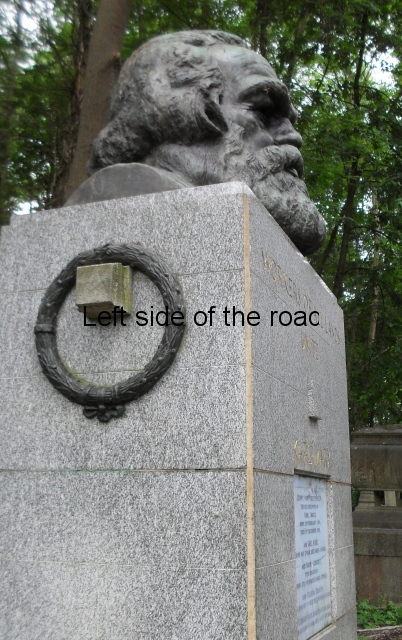

On each side of the plinth is a single olive wreath, close to the top and centred, in bronze. This can be interpreted in a number of ways, as in the past such wreaths have come to have various meanings. One would be a celebration of the successes and the achievements of Karl Marx. He was the first to formulate a coherent ideology which, if implemented in the manner expressed in the quotes on his tomb, is exclusively of use to and benefit for the working class and all other oppressed and exploited peoples of the world.

It would be difficult to suggest that the olive branches represent peace. Like all great ideologists many of Marx’s words can be taken out of context and thereby remove the revolutionary nature of Marxism. In his early writings Marx was clear on the need to complete replace the old system and replace it with one that was designed purely for the working class. If he had any doubts about that (which I don’t think he did) before 1871 he was clear in his own mind, and in his writings, that such a change would invariably have to be violent after the experience of the Paris workers in 1871. The ferocity of the reaction and the slaughter that accompanied the defeat of the Commune showed the world that once capitalism’s power was truly challenged they would stop at naught to crush any such attempt. Events worldwide in the almost 150 years since the Commune has proven that thesis time and time again.

There is nothing on the back of the plinth.

As an aside here it’s worth mentioning that at the time that the CPGB was making moves to commemorate Marx with the structure in Highgate Cemetery the Party itself was making moves to go against the very revolutionary essence of Marxism. The Party had already adopted the revisionist British Road to Socialism as its programme. By the end of the same year as the unveiling of the monument the Party leadership would accept the attacks made on JV Stalin by Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Subsequently the CPGB took the revisionist, capitulationist, side in the upcoming Polemic in the International Communist Movement.

Target of Vandalism

From the early days the monument has been the target for anti-Communist and Fascist elements within British society. In 1960 it was painted with yellow swastikas and suffered a couple of inept bombing attempts in the 1970s. There was also a paint attack in 2011. However, things have heated up recently as there have been two attacks this year (2019).

The first was on the night of 5th February 2019 when Marx’s name was chipped away at by a hammer. This might have done irreparable damage to the original marble plaque but it wouldn’t take too much to get a replica made. Whether the money or the will is there is another matter. Then, less than two weeks later, on 15th February 2019 it was daubed on three sides with anti-Communist slogans. These were easily cleaned off but I think the strip of red that runs down the facsimile of the plaque when I visited (in June 2019) was a remaining sign of that paint attack.

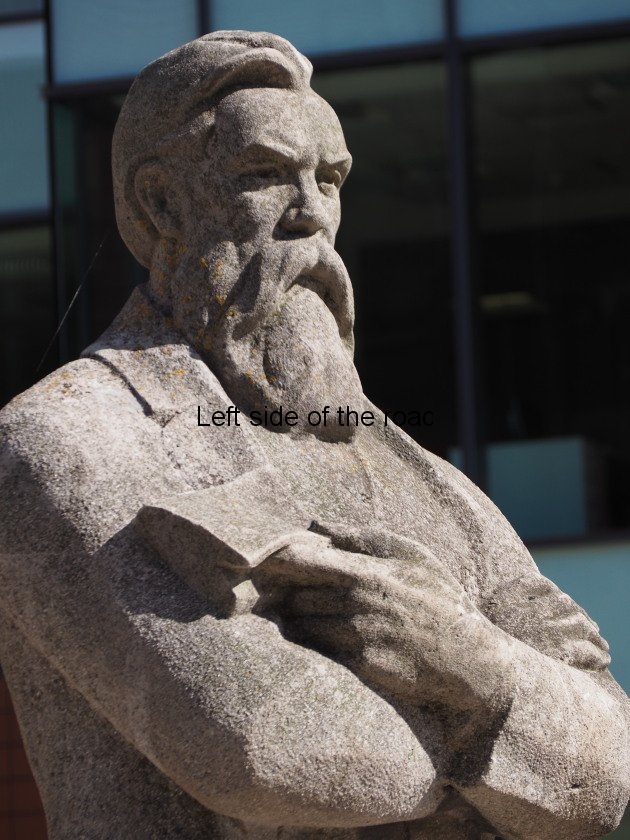

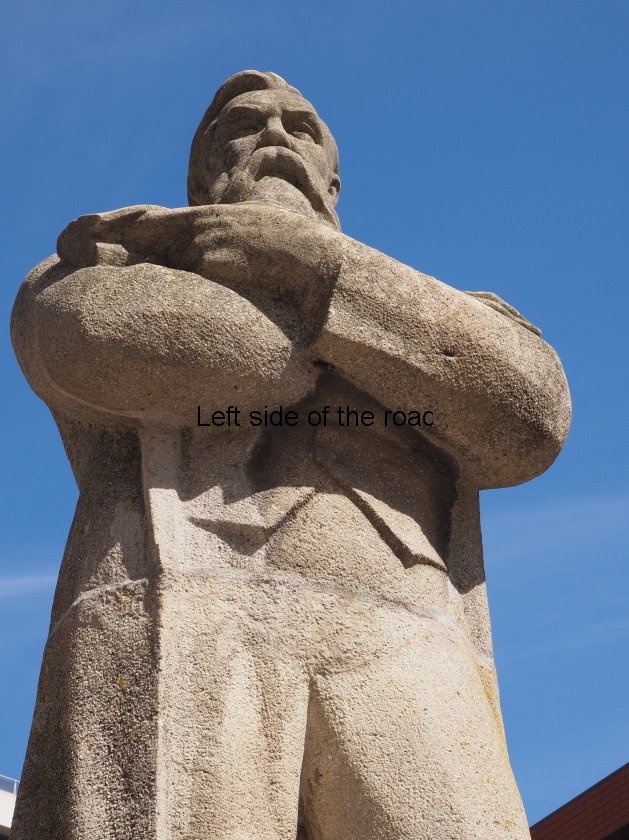

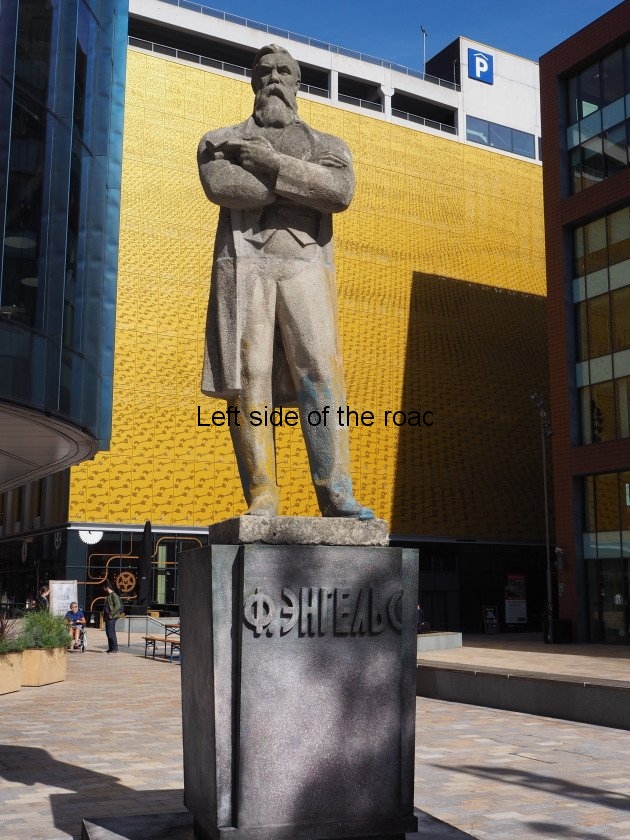

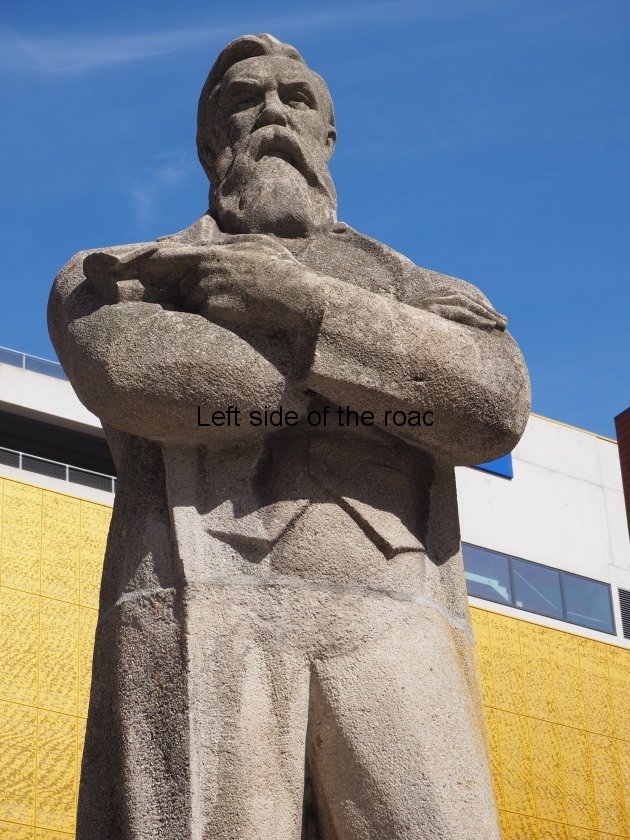

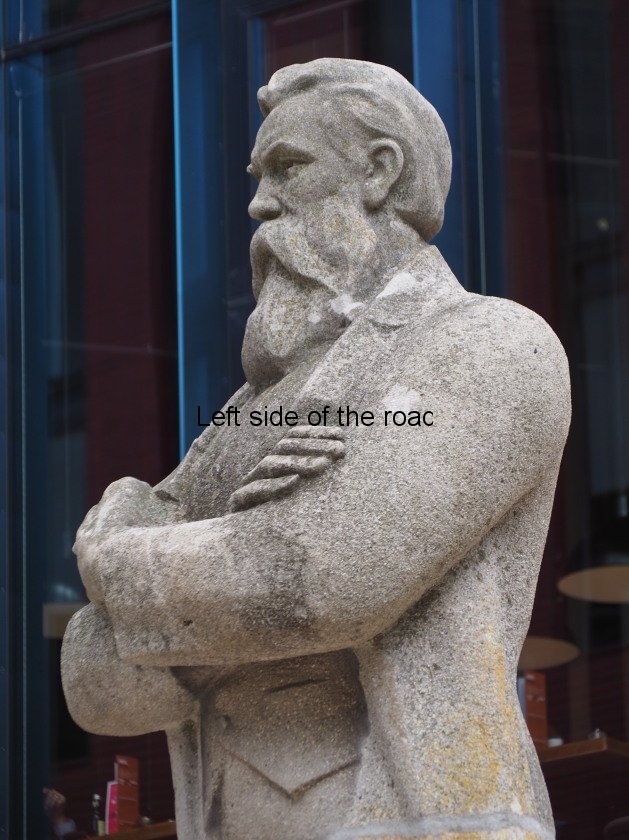

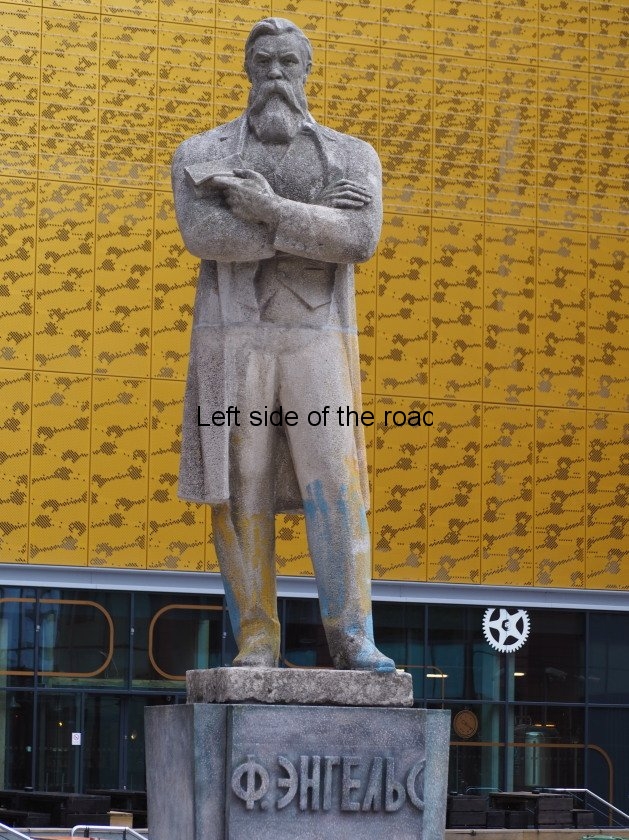

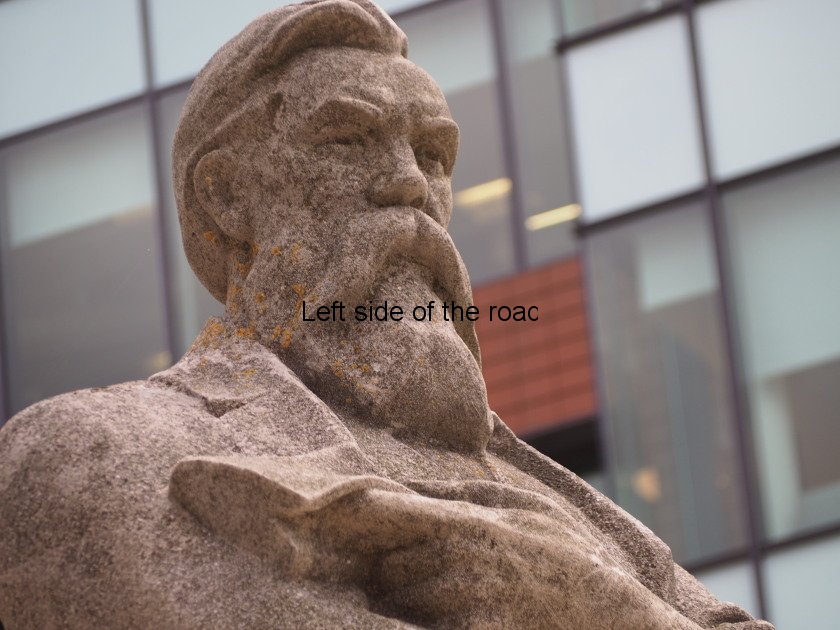

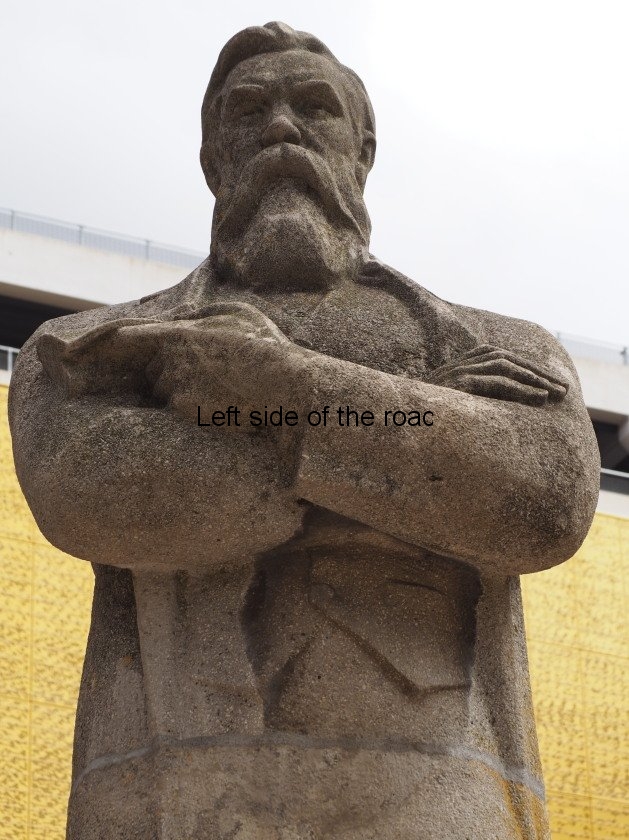

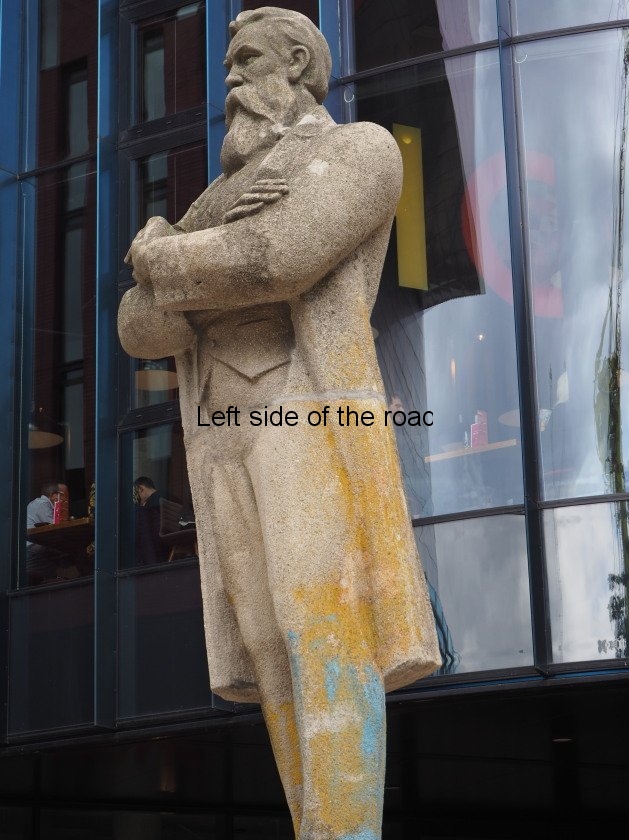

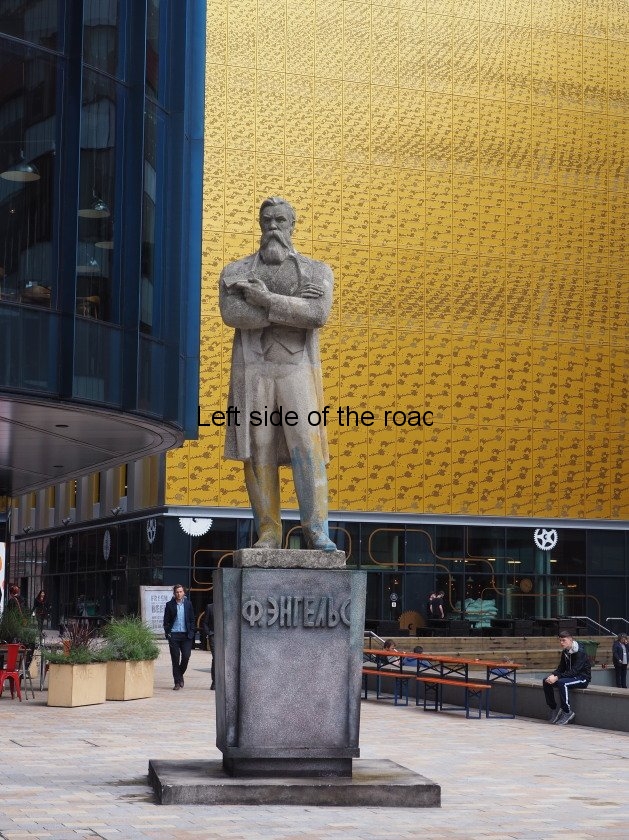

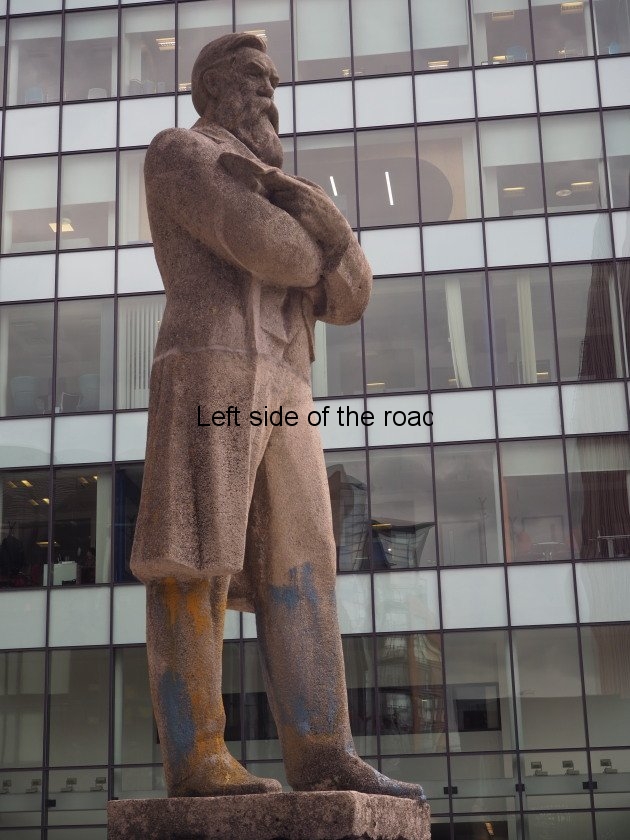

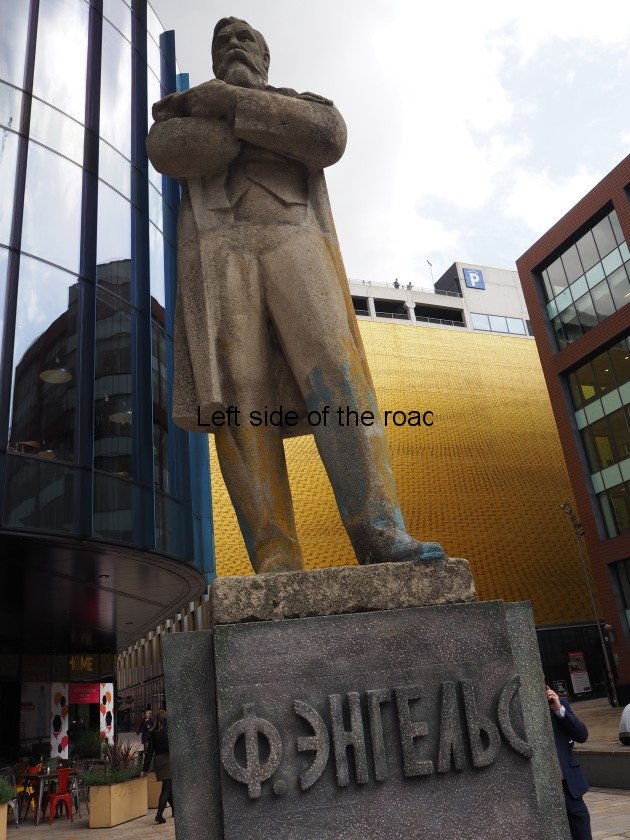

For those who believe and follow the ideas of Karl Marx a visit would be recommended if in the vicinity. The Marx monument was the result of a local, British initiative. The raising of a statue to Frederick Engels in Manchester was as a result of the failing of the revisionist system in the Ukraine. That’s also worth a visit.

How to get there:

Get to the centre of Archway (by the underground station) either by Tube or Bus. Then walk up Highgate Hill, away from the centre, passing the hospital and a statue of Dick Whittington’s cat, and at the top of the hill, by the church on the left, turn into Waterlow Park and exit by the bottom entrance which is right beside the entrance to Highgate Cemetery.

Location:

GPS:

51.5662

-0.1439

DMS:

51° 33′ 58.32″ N

0° 8′ 38.04″ W

A paper map is given after paying at the entrance but if you want an idea before you arrive click on the above for a pdf version.

Opening Times and Entrance Costs:

Daily: (except 25 and 26 December)

10am to 5pm (March to October)

10am to 4pm (November to February)

last admission 30 minutes before closing.

Adults: £4.00 (capitalism even makes money out of revolutionaries – and the dead)

Under 18’s: Free