Bas Relief – Bajram Curri

More on Albania …..

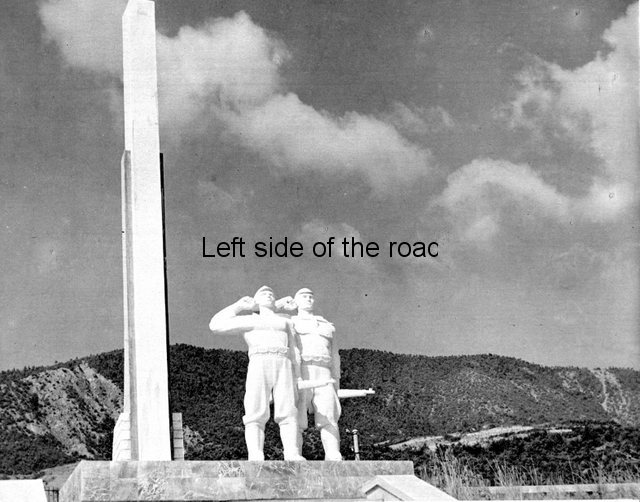

Bas Relief and Statue at Bajram Curri Museum

The early Albanian lapidars were relatively simple affairs, uncomplicated memorials to those who had died in the National Liberation War against Fascism and for Socialism. Come the Albanian ‘Cultural Revolution’ – starting in the late 1960s – the intention was to use such monuments in a much more educational manner as well as establishing a distinctive Albanian identity. This meant that artists who had been educated and trained under the Socialist regime were encouraged to depict events and memorials in a much more figurative manner. Examples of this approach are seen in the Musqheta monument in Berzhite and in the Peze War Memorial. As the Cultural Revolution moved into the 1980s a new approach developed. This was one where the monument told a story which had developed over time, showing a continuum of the struggle. This is seen, in a truly monumental manner on the Drashovice Arch (close to Vlora) and in the Albanians Mosaic on the façade of the National History Museum in Tirana but also on the more modest, at least in size, bas-relief and statue in the north-eastern town of Bajam Curri – although it also presents some new questions of the meaning of Socialist art.

It appears that the Museum, bas-relief and statue were considered as a whole, all being constructed in the mid-1980s. The Museum was looted in 1997 and there has been no efforts to re-open it in the intervening years. Whether the looting was prompted by greed or political revenge I can’t say. Neither the bas-relief nor the statue – which carry a significant political message themselves – do not seem to have been damaged in any way. The area also doesn’t display the same sort of neglect that plagues so many public spaces throughout Albania. Since my first visit in 2011 a small cafe has been opened in the area behind the bas-relief but the area hasn’t degraded in any significant manner.

Bajram Curri – Looted Museum

The Bas Relief

This sculpture is a visual representation of the history of the struggle for independence over the centuries and ends with the situation in the country at the time it was completed – moving forward with the construction of Socialism. Such a depiction obviously draws parallels to how the Church (in Western, Christian societies) decorated the interiors of their buildings in an effort to ‘educate’ the illiterate ‘faithful’.

This was not the case in Albania, the battle to combat illiteracy being one of the first success of the Socialist state, a goal which was achieved by the early 1950s, such an achievement being even more impressive taking into account the recent history of the country and the threat to its very existence that it faced from antagonistic neighbours (first Greece, after the re-establishment of the Fascist collaborationist monarchy) and then, from 1948, the renegade Yugoslav Federation) as well as the two imperialist powers of Britain and the United States.

At the same time the visual representation reinforced the message the Party of Labour was attempting to inculcate amongst the people, that their independence had been hard-won and if they wanted to go forward then it would take more and even greater effort, against vicious opposition and enemies, in the future.

The story reads from left to right.

The fight for independence

In the top left hand corner are two standing men. The one at the rear is holding a spear, his hand quite high up the shaft, and in his left hand an escutcheon, a triangular-shaped shield, although only part of it is seen as the other warrior hides most of his comrade. This other fighter has his right hand on the hilt of a short sword, seemingly in the process of drawing it. The sheath is hidden behind a small, round shield. Both the shields have studs around the perimeter, providing greater strength. The round shield also has an image in the centre, although it’s difficult to say exactly what it represents. The different shaped shields indicate the different roles these two fighters would play in a battle, a difference from defence and offense.

Both of them are sporting large, bushy moustaches and the one in the front has long hair, tied at the back. It seems that for a long time in Albania’s history of resistance to foreign invaders abundant facial hair was considered a sign of virility and is so depicted in older paintings and then up to the age of early photography. The spear bearer has his head covered with a qeleshe (the, normally white, brimless, felt cap). The sword bearer is bare-headed and has his jacket open and loose.

They are marching forward, as if advancing towards the enemy, with both their right legs shown in front of them. On their feet they wear the opinga shoes, the ones that have the toe slightly bent upwards, a type of footwear that was common in Albania for centuries.

These two men represent the fight for Independence from the 15th century when the national hero, Skenderberg, was leading the battle against the Ottoman Turks. Skenderberg as such is not depicted here but as in many Albanian lapidars neither is he totally absent – as we shall see later.

The next figure, to the right of the first two soldiers, I find slightly problematic. Here we have a man on a horse in the act of firing a primitive rifle. I assume this is now bringing us closer to the present day, to the battles that took place in the 19th century, going by the look of the weapon. He is upon a large horse, the head of which obscures the earlier mention fighters, and gives the impression of movement as if it were in the middle of a charge.

What is problematic about this image is that Albania is a mountainous country and virtually all the successes of the Albanian fighters for independence on the battlefield have been where they use the terrain against their enemy. This was the case in the 15th as well as the 20th century. Horses would have been in very short supply as fighting animals. If used at all they would have been used in the role as draft animals, as would have mules and donkeys. Animals are not very common on the lapidars in general but can be seen in this role on the Pishkash Star.

Yes, Skenderberg is often shown riding a horse, but then he was a ‘lord’ and not one of the hoi poloi. In the battles depicted in the murals of the Historical Museum in Kruja, for example, he is shown leading a cavalry charge against the Turks but even in those images we see that the Albanian foot soldier would use such nominal superiority of the Ottomans against their enemy, raining stones down on them as they went through narrow defiles in the mountains. Basically, if Skenderberg had used such open field tactics against the occupier then he wouldn’t be remembered today, having died in his first battle. It makes for a dramatic mural, especially such large ones, but I have my doubts of how close to reality they might have been.

But getting back to the bas-relief in Bajram Curri. All the images (I can’t think of a lapidar where this is not the case) where someone is shown actually in the act of firing a weapon that weapon is pointed downwards. That makes sense. Without having to give any further explanation we are told that these are fighters in the mountains, ambushing their unsuspecting enemies. The soldier on the bas-relief is shown firing downwards, from a horse. He is, therefore, either shooting someone laying on the ground or from a high vantage point. If the latter why on a horse – it really doesn’t make any military sense.

Like the first two fighter he also has a busy moustache and is dressed in traditional countryside clothing, including a qeleshe on his head. He doesn’t appear to be sitting on a saddle but there is evidence of embroidery on the blanket he’s sitting on.

The horse might have been included to create a feeling of dynamism but it goes against historical reality and sense. This is mirrored in one of the murals in the looted museum (see the picture above) where a horse is included when it wouldn’t necessarily have been there in reality. Perhaps a situation where an artist, an intellectual, sees the world from their own perception and not from a study of what actually existed at the time.

The last fighter on this side of the relief brings matters even closer to the present day. This is a Partisan from the National Liberation War, fighting in the hills and firing downhill at the enemy. He is in a pose seen on other lapidars: kneeling on what is obviously uneven ground, thereby stressing that he is in the mountains; the image of rocks in the bronze, again making the point that the success of the Partisans was dependent upon their dominance of the terrain; the machine gun (this one on a tripod and with a belt of ammunition that can be seen hanging down below the firing mechanism) firing downwards, another reference to mountain warfare but also suggesting an ambush, the tactic of guerrilla fighters; he’s wearing a cap on which (in profile) can be seen the star, indicating that he is a Communist; the bandana around his neck – yet again a sign of his political allegiance; around his waist, attached to his belt are ammunition pouches, three of which can be seen here; and, finally, on his feet he is wearing the 20th century version of the opinga shoes, indicating that he is from the countryside and showing that the Partisan army was one that included both workers and peasants.

Partisan firing from the hills

Now all these fighters are facing to the left – the opposite direction to the vast majority of the other individuals on the panel. This indicates that this is the fighting that has gone on in the past, the past being shown as something that is in the opposite direction to the future, the direction in which the young people on the right hand side are marching. Even the flared muzzle of the machine gun of the Partisan is actually outside the edge of the rectangular panel, as if to emphasise the connectiveness, yet separation, of the other events depicted.

The next scene, as we move towards the right, is a common one and has appeared on other lapidars, for example, the Mosaic at the Durres War Memorial. This is the entry of the Partisans into town after the defeat of the occupying Fascists. In this particular scene we have four actors, two Partisans – a male and a female – an older civilian woman and a young child.

However, in this image in Bajram Curri there are a few discrepancies which will need a bit of thought and analysis to see how it fits into the story of lapidars in Albania.

To the best of my knowledge Bajram Curri wasn’t even ‘liberated’ in the way that it was in other towns and cities in the country. Bajram Curri as such didn’t even exist until after liberation, when the town was chosen as the administrative centre of the Tropoja region and given the name of the Kosovan hero and fighter for independence of the early 20th century. The town is not easy to get to in the 21st century let alone before any thought of a transport infrastructure was created during the Socialist period. Even today the minibus from Bajram Curri to Tirana goes via Kosovo before returning to Albania just north of Kukes.

So the scene which shows a meeting of the Partisans with the civilian population, as well as a parade with the young, bare-footed girl being carried by the female partisan, seems to be an invention. It did happen in many places in the country but not necessarily in this remote region. The many dead commemorated in the town’s Martyrs’ Cemetery, down the hill at the entrance to the town proper, would more likely to have fought and died in other parts of the country or, possibly, fighting with the Yugoslav partisans across the border.

There also seems to be a discrepancy with the uniforms. The great coat of the male officer seems too modern for what would have been used by a Partisan from 1939-44. He’s dressed more like an officer of the Army of the People’s Republic of Albania than a Partisan who had just come down from the hills. He’s just too smart. His great coat fits too well, with a dispatch case hanging from a strap over his left shoulder whilst he has a rifle hanging from a strap across his chest over his right shoulder – the end of the rifle barrel seen just behind him.

One possible reason for this is the late date of the bas-relief (1986),which makes it one of the latest. In fact, I can only think of one later lapidar and that’s in the centre of Lushnje, dated 1987. There are a number of reasons why the creation of lapidars came to an end around this time, not least of which was the death of Enver Hoxha in April 1985.

The inability of those who followed him in the leadership of the Party of Labour of Albania to maintain Socialist construction meant that the ‘Cultural Revolution’, which had been losing its momentum for some time, really came to a halt soon after Enver’s death.

Isa Balla, the sculptor, would not have been born at the time of liberation. Unlike many of the sculptors that created works in the late 1960s and 70s he would have had no personal connection to the Partisans. However young they might have been in 1944 many of those artists had had some experience of war and those who fought in it.

Assuming that Balla came from the Tropoja region (most one-off works of art catalogued by the Albanian Lapidar Survey were created by sculptors from the region in which the work was located – even if it was only as an assistant to a more experienced sculptor) he would have been very much more aware of the modern, Socialist Army. The threat posed by Yugoslavia from 1948 onwards meant that this region would have had a significant military presence right up to the end of the 1980s. That knowledge is what gets fed into his work.

This displays a possible growing separation of artists from their own history. Creating his masterpiece – I still like it despite its flaws – in 1986 Balla then seems to have disappeared. At least I haven’t come across any other works by him elsewhere. But with these caveats, back to the scene.

It depicts the meeting of two generations apart from anything else, two generations who had fought for and desired independence if nothing else (nationalism without socialism rapidly heading towards fascism). The young Communist Partisan Officer – he has a red star on his cap – is shaking hands with a much older women, one old enough to be his grandmother. She is dressed in traditional peasant clothing of the mid-20th century, with a loose sleeved dress and a head scarf (though not the hijab or any other head covering indicating an Islamic influence). Their rights hands are already clasped and she appears to be moving her left hand towards his so that she cane have his hand in both of hers, a sign of warmth, friendship and affection. This is accompanied with eye contact between the two of them.

The double-headed eagle

The reason for this closeness between them is demonstrated by the image above and behind the couple. Here there is a stone arch with a double-headed eagle carved into the keystone. The woman in front of her home is declaring her long-held wish for independence, which was only really achieved with the final victory over the Nazi invaders on 29th November 1944. Hence the warmth of their meeting.

The next image, that of a female Partisan carrying a young child on her shoulder, is also a familiar trope in liberation tableau. This is very well represented in the Bestrove Mosaic, where a poor boy is holding hands with a male Partisan, admiration obvious on his face as he looks up to one of his heroes and the statue in Berove, where the male partisan has his hand resting protectively on the shoulder of an early teenage girl. This all makes sense. Zogu, the self-proclaimed ‘king’ who ran away to Britain once his erstwhile Italian masters decided he was of no further use, would never have consorted with the poor if he had been arriving back in the country. Capitalism has had centuries to overcome poverty yet it is becoming more acute, whether it be relative or absolute, and only a new approach to the problem will provide a permanent solution.

So here we are presented with a heart-warming image. The little girl is happy even in her poverty (she is bare-footed). She has her left hand high in the air above her and is waving at an unseen crowd. She’s smiling, perhaps the time of her suffering is at an end? At least there are now people who offer her young life some hope.

Partisan and child

Yes, it’s idealistic. But the aim of Socialist Realist Art is to present a different future. In a predominantly agricultural society as Albania was before 1939, ruled by tribal/feudal landlords the Albanian Communist Party offered: land to the peasants; education for all; control of the country’s resources by the working people; true independence, although this brought with it a whole shed full of problems; and, most importantly, hope for the future. But all that had to be fought for and the greatest battles might well have been in the future. A revolution is not the solution to problems, just the start of the solution.

(And, in a society where capitalism is presently ruling the roost, we have to remember that ALL victors in a war use images of a happy population during periods of success to promote their own particular political and economic system – and hope everyone will forget times when things go against that same system – such as Dienbienphu (where the French imperialists were defeated in 1954) and the crashing of the tanks of the National Liberation Front into the US embassy in Saigon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City) in 1975.)

The female Partisan is very well dressed, wearing a cap with the Communist star and a bandana (which would have been red) around her neck. (There seems to be another anachronism here in the style of her shoes.) She is confident, marching forward and carrying the young girl into an uncertain future but one that would be beneficial to the poor if they took the opportunity into their own hands. (There also seems to be a lot of hair, not as bad as the awful representation of young Liri Gero in Fier, but seeming to presage later ‘developments’ in Albanian sculpture.)

The central group, an old man and two young children (a boy and a girl) is replete with symbolism. The backdrop to the group is a huge double-headed eagle with a large star just above the heads. This is a development on from the small symbol of the eagle carved into the stone of the arch previously mentioned. The star means that the struggle for independence of the past had eventually been achieved under Communist leadership and (although not considered at the time of this lapidar’s construction but which today has become a reality) could only be maintained under such a social system.

The figures represent a unity of the past with the present (a grandfather figure and very young children) but also the idea that what had been fought for in the past was important in order to make a bright future. The old man is dressed in traditional costume, elements of embroidery being evident on his jacket and trousers. He wears a qeleshe on his head and the headband becomes a wide scarf which is thrown back over his left shoulder. On his feet are the opinga shoes. He has the obligatory bushy moustache of his generation but what really connects him to an even more distant past is the musical instrument he is playing. This is the gusle, a Balkan version of the lute, which was played not by plucking the strings, as in western Europe, but with a bow.

Playing the gusle

(This picture is supposed to be from Herzegovina and is dated 1823. Why it has a symbol which is very much Albanian in origin is a mystery to me.)

What is especially interesting about this instrument is the neck, or more specifically the carving at the top of the instrument. This is where Skenderberg appears in the tableau. Most of the depictions of Skenderberg, whether it’s on the statues of him, riding his horse in Tirana; standing in Peshkopia (where it is held in his left hand, against his body); in the murals in the Historical Museum in Kruje; or the numerous paintings of him throughout the country he is always shown with a helmet that has the very distinctive design of a ram’s head with very long, swept back horns.

(Travelling around Albania visitors don’t have to be interested in history to notice this symbol of Skenderberg as it is used by the Kastrati Oil Company as its logo and appears on all their petrol stations. Kastrati is a version of Skenderberg’s family name (Kastrioti). This present company would have been the basis of the nationalised oil company under the period of Socialism but which the people of Albania allowed thieves to steal from them in the early 1990s.)

Listening to the music

On the right hand side of the gusle player stands a very young girl. She’s wearing a dress and her long hair is tied in a pony tail by a large ribbon. He stance is interesting. Her right forearm is resting on the old man’s thigh, with her hand on his knee. Her left elbow rests on her own right wrist and her left hand is under her chin, supporting her head as she listens to what is being played. She’s looking up to his face and her mouth is slightly open, possibly singing along in her own manner.

The young boy is sitting on the ground to the left of the old man, his left arm stretched out behind him and supporting his body as he leans back. His right hand holds the top of a book which is resting on his right thigh. He too is looking upwards but more to the little girl than the old man. He’s wearing a short-sleeved shirt, shorts and sandals. We know he’s a young pioneer as around his neck is a scarf, the triangle rucked up over his shoulders.

All three are on different levels and it looks like they are out in the countryside. This is, again, a reference to the mountains and a trope that appears often to stress the importance of the mountains to Albanian culture.

The right hand section refers to the period after the war and the construction of Socialism.

The backdrop for these images is, again, a common aspect of such monuments. This is where there’s an image that defines the exact location of the lapidar. This was seen, for example, in Durres on the bas-relief that commemorated the tobacco workers strike. There an image of the Venetian tower pinned the event to the town. In Bajram Curri the image that plays that role is the outline of the mountain range that dominates the town. In fact, if you walk into the middle of the road below the museum and look north along Rruga Sylejman Vokshi you will see exactly the outline that is carved into the bronze of the lapidar in the distance.

Superimposed over this mountain scene is a single electricity pylon. One of the achievements of Socialist Albania was the electrification of the country, providing power to even the most isolated parts of the country. This was an achievement on the same scale as the electrification of the Soviet Union although the geographical scale of the two countries was so different. The Soviet Union was the biggest state in the world at the time and after its revolution Albania was one of the smallest but taking into account the base point from which they started the achievements were as important and what achieved as impressive. This pylon appears here as a recognition of the construction of the dams and the hydroelectric plants which created Lake Koman, only a few kilometres down the road.

In the top left of this right-hand section are two soldiers, both of them having the thumbs of their right hands behind the strap of their rifle which can be seen behind them. One is in normal uniform and looks out at the viewer. The other is in winter camouflage and is in profile, looking towards the outline of the mountains. This implies that the Socialist army is one which is not the same as an army in a capitalist state. It aims to protect the people and is not an aggressive force which is sent to different parts of the world to defend the interests of the ruling class.

In fact, the Albanian Army was one that abolished the hierarchical system of ranks and placed more reliance upon an army that was more of a militia where the population were responsible for defending their country – the oft ridiculed (by those with an anti-Socialist agenda and/or ignorance) bunker system was an integral part of this strategy. But Albania did have a hostile neighbour – Yugoslavia – and a huge area in the north-east of the country, which was very sparsely populated, bordered that potential enemy. For this reason the army had to have professionals who were trained to work in the potentially hostile climate of snow-capped mountains for a significant portion of the year.

Below the soldiers there’s the image of a miner pushing a mineral tub. This alludes to the mining of high value minerals that used to take place in the Tropoja region. I would like to think that even when these mines were working concerns during Socialism that machines would have been moving these heavy tubs from place to place but it’s difficult to represent industry in such a limited space. The miner is in profile and he leans forward as he strains to move the heavy, fully laden tub. He wears heavy protective clothing for the nature of his job, a pair of heavy boots and a helmet on his head.

It was only under Socialism that the mineral resources of Albania were exploited for the benefit of the population. The town of Elbasan, for example, was the location of one of the biggest chrome processing plants in Europe – now almost totally abandoned. And there doesn’t appear to be a great deal of activity in the Bajram Curri area at the moment. This is despite the fact that the area is supposed to be extremely rich in some of the most expensive and rarest of the minerals used in the expanding worldwide electronics industry. However, there are few attempts to extract these minerals for the benefit of the Albanian people – the exploration, exploitation and profits being offered to foreign-owned multi-national companies. This includes large reserves of platinum and associated elements. This is an issue throughout the country with lack of investment leading to an increasing number of accidents and deaths which have led some miners to get their courage back with a recent spate of strikes in Bulqize area (in the early part of 2016).

Collective Farmers

But Albania is also a fertile region for agriculture and the State Farms and Co-operatives are represented on this lapidar by a male and female agricultural worker, both of them carrying huge sheaves of wheat – the male with it cradled in his arms and the woman holding hers above her head with her right hand, resting some of the weight on her shoulder. (This is a similar image to that on the First Party Cell monument in Proger and the ‘Toka Jonë – Our Land’ sculpture in the centre of Lushnje.) They are both wearing the standard working clothes of the 1980s (but there’s evidence of embroidery on the woman’s blouse and there’s an apron around her waist). The woman holds a small scythe in her left hand, that hand resting on her waist. He is looking out towards the viewer whilst she is looking towards her left, her face in half-profile.

The Army, industry and agriculture have now been represented in the new Socialist society and the three other individuals on the sculpture represent the youth of the country – the future in a figurative sense.

Here we have two young males, both in profile, marching towards the right hand edge of the panel. The one nearest the viewer has a pickaxe balanced on his right shoulder, holding the wooden handle close to its end in his right hand. The other, all but his face obscured, is carrying a shovel. These will be students who are off to do their ‘voluntary’ work.

Revolutionary Students

I’ve put the word voluntary in parenthesis as, especially as we came into the 1980s, a growing number of students, not having any experience of society before liberation and thinking themselves ‘special’ and manual work being beneath them, might have resented this obligation. However, it is a standard idea of the integration of the young people in a Socialist society into the world of work. In a country where illiteracy was a problem for the overwhelming majority of the population before the 1940s the elimination of this feudal heritage was one of the first achievements of the new society. But in a Socialist society there are both rights and obligations and young people who never would have had chances of a university education in a Zog run society had the obligation to make their contribution to the society which had given them certain privileges. A possible reason for the students playing such an active role in the counter-revolution of the 1990s was possibly due to this idea that ‘intellectuals’ are somehow different from the rest of the population – but this is something to be explored later and elsewhere.

However, in this tableau the students seem happy to do their bit. It’s worth mentioning that young people were very much involved in the building of the railway network that was created throughout the country. But all that effort has been just let to go to waste in the 25 years or so since the counter-revolution and now the rail infrastructure is in a sorry state – virtually in terminal decline.

The two young males are accompanied by a young woman. She’s facing out to the viewer and in place of tools she carries a book in her right hand. Here we have another allusion to the unity of education with the world of work.

Poppy – Albania’s National Flower

This covers the principal images but there are still a couple of other points of interest. In the bottom, right-hand corner, just to the right of the leg of the female collective farmer there’s a single poppy. The poppy is the national flower of Albania but the only other monument it appears (so far, to my knowledge) is as an element of the statue in the Lushnje Martyrs’ Cemetery – where it accompanies sheaves of wheat in the hand of the young boy standing on the female Partisan’s thigh. The Bajram Curri bas relief and the Lushnje statue are only a couple of years apart in their construction (1984 in Lushnje, 1986 in Bajram Curri) so I’m not sure if there was a change of direction, perhaps only subtle, from the emphasis on Communist iconography to a more nationalistic representation.

In the extreme right hand corner there’s the date of the inauguration (1986) under the name of the sculptor (Isa Balla). This is another development that seems to accompany those lapidars created in the 1980s. Up to that time the majority of the monuments gave no indication of the identity of the creators. This was in line with the Socialist approach to art. An engineer didn’t have his/her name in a prominent position on something they had made so why should an ‘artist’. Here we are introduced to the question: what exactly is an artist? Is not a railway engine, in many respects, as much a piece of art as a sculpture? Many hundreds of people would have had an input in such a machine. Even in the bas-relief here in Bajram Curri Balla would have designed the statue from which the mould for the foundry was made but there were many more people, whose skills were vital for the final product, who don’t get a mention but without whom the bas-relief would not have existed.

This is another indication that the ‘intellectuals’ were starting to draw apart from the rest of the population and were becoming ‘special’ in the society. A dangerous development when what happened only a short six years after this lapidar was unveiled is taken into account.

So far I’ve been unable to come up with any more information about Balla and haven’t come across other works of his in other parts of the country. If the normal procedure was followed he would have very likely been a local artist, attempts being made in the past to have a local influence, connectivity, to a substantial work of art – even if, at times, they were teamed with a much more experienced sculptor.

Another point to be made about this work is that it is the first, where Partisans are depicted armed, that a woman does not carry a weapon. Here the only woman soldier is shown playing the role of a mother, caring for a vulnerable young child. This may be a small matter but when we consider the idea of the Albanian Cultural Revolution and the way that women would be depicted in works of art it’s interesting that the female Partisan is not as powerful here as she appears on other lapidars.

This bas-relief demonstrates a number of significant changes in the cultural direction in Albania in the second half of the 1980s, after the death of Enver Hoxha. It was also one of the last major lapidars to be created in the country before everything fell apart in the early 1990s so, perhaps should be seen more in the context of what followed its creation rather than what came before.

Bajram Curri Statue

The Statue

Just a few meters to the left of the bas-relief stands a large statue of the Kosovan/Albanian patriot and fighter, Bajram Curri, the one who gives his name to the town. Although not born in what are now the borders of Albania he was considered an Albanian hero as Kosovo has for long been considered a real part of the mother country, even to this day. This dispute of where the region of Kosovo belongs was one of the reasons for the antagonism between Yugoslavia and Albania from 1948 to the late 1980s.

During World War I Bajram Curri organised guerrilla units against the Ottoman Empire and after the war played a role in different levels of the Albanian government. What would have endeared him to the victorious Albanian Communist Party after the defeat of the Nazis in November 1944 was Curri’s opposition to, and even taking up arms against, Ahmet Zogu (who later became the self-proclaimed ‘King Zog’). Curri lost in the war against Zog and was killed in 1925 just around the corner from the present town, in the Valbona Valley.

Bajram Curri

The statue stands on a plinth on the edge of the museum complex and looks down on the main street into the town. He stands with his legs apart as if stepping forward with his left leg leading. His head is slightly raised and he looks straight ahead. His left arm is at about 45 degrees to his body with the fingers of his hand splayed to their fullest extent. His right arm is hanging straight down, slightly away from his body, and he holds a bolt-action rifle just in front of the firing mechanism. The rifle itself is slightly raised over the horizontal.

Like many of his contemporaries Bajram sports a bushy moustache. On his head is a fez and he wears a long, heavy great coat over a tight, leather shirt and a pair of trousers known as tirq. On his feet he wears the opinga shoes. Around his waist he has a brez (a wide, cloth belt) into which is tucked a pistol. A pouch hangs from the belt.

The pistol is interesting. It has a curved grip which is covered in nodules which were, presumably, to give a better grip in wet conditions. This appears in other statues of Bajram Curri’s contemporaries, such as Isa Bolletin in Shkoder and a very recent one (2012) of Adem Jashari by Mumtaz Dhrami in Tirana. I assume it’s a true representation of the weapons used at the time. I’ve forgotten to check this in the different museums where such arms are on display.

Fuat Dushku was the sculptor and it was inaugurated in November 1982 on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the National Independence from the Ottoman Empire – although true independence had to wait another 42 years with the liberation of the country from the Nazi invaders under the leadership of the Communist Party of Albania (which was to become the Party of Labour of Albania) with Comrade Enver Hoxha at its head. Dusku was also responsible for the statue of Resistance on the Durres seafront and also the Four Heroines of Mirdita in Rreshen – the latter being destroyed by the reactionaries in the 1990s.

The Museum

Bajram Curri – Mural in Looted Museum

The Museum building is quite large and I’m not sure if all of it was actually used for the display of artefacts from the National Liberation War and other, previous, struggles for independence. I only had the opportunity to stick my head in and take a few quick pictures of the damaged murals a few years ago. Whether there are any plans to re-open the museum I wouldn’t know. It is happening in a few towns around the country so it’s not impossible that something will arise from the ashes of destruction in the future.

Location:

The main road into Bajram Curri, from Fierza or Kosovo, heads up hill, the rest of the town off to the right. The (now looted and closed) Museum, where the monuments are located, is at the top of this hill, the statue of Bajram Curri himself being an obvious landmark.

GPS:

N 42.35690

E 20.07312

DMS:

42° 21′ 24.84” N

20° 4′ 23.232” E

Altitude:

384m

More on Albania ……