Dogu Ekspresi on Platform 1 – Ankara Gar

Dogu Ekpresi from Ankara to Kars

or 24 Hours and 1,200 kilometres through a beautiful part of eastern Turkey

There were two reasons to go through Turkey on the way from Albania to Georgia. The first was to visit the Ayasofya in Istanbul, the second to take the overnight train from Ankara to Kars (in the far eats of Turkey). The first was aborted. The crowds were horrendous, even early in the morning, and the experience inside the building wouldn’t have been too good if I had had the patience to wait in the queue. The second was achieved and was well worth it.

Although the information below has already been posted on this blog in relation to the ‘High Speed’ train from Istanbul to Ankara it won’t do any harm to repeat it here.

Booking

There are different routes to booking websites whatever you want to buy. However, I have found that many of those routes lead to a dead end, especially if you want to go to a page in a language other than the native one.

I found the TCDD site here the one that worked for me.

Book as long in advance as possible. I’m not talking about months as the tickets aren’t released until a few weeks but if you leave it to a matter of days then you will be pushed for choice.

So the process

Once on the site click on ‘English’ in the top tight corner. If it doesn’t go to English try until it does. Then choose your starting point and destination, the date of departure then whether you want single or return and, if so, the date. Click Continue.

This brings up the available trains on your date. Decide a time, click on the arrow for the drop down menu for class of travel, i.e., Pullman or Örtülü Kuşetli (4 berth Couchette). Click select. The price for your class of travel will be shown. Click Continue at the bottom of the page.

Then will come up a diagrammatic representation of the carriage with the class you selected. Click on your choice of seat WITHOUT a cartoon face of a man or woman. You will be asked to select your gender and if the system likes you the seat will be selected for you. The system will not allow you to choose a compartment if it already has a booking from a person of a different gender and an error message will come up. Presumably that’s not the case if you are booking as a couple or group. Scroll down and fill in your personal details. Once completed click continue.

This will take you to the payment page. Remember – at least those from EU countries (and even the UK as it is about to leave) if you attempt to make a payment with a debit/credit card from now on you will get a code sent to your registered mobile number so have your phone handy. The code is only valid for about 10 minutes. Complete all transactions requested and you will receive confirmation of a ticket. This will also be sent to your email address.

Cost

Pullman (reclining seat, 3 abreast) TL 58

Örtülü Kuşetli 1.Mevkii (Business) (4 berth couchette) TL 77.50

Ust is the upper bunk, Alt the lower.

If the finances allow it I would suggest going in the couchette, it makes for a much more relaxing journey – unless you are interested in experiencing the real Turkey when on a train.

As far as I can see these prices don’t change depending upon when you book – as is the case in the UK.

(There’s also the option of taking the Tourist Dogu Ekpresi. Here you travel in a 2 berth couchette and the cost is TL 480. It takes 1 day, 7 hours and 3 minutes, departing at 16.55 and arriving at 23.58 the following day. It only departs on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The extra time is to allow for side trips along the way. I also assume that all meals are included.)

Journey Time

24 hours and 13 minutes.

Depart Day 1 at 18.00, arrive Day 2 at 18.13.

Departure from Ankara

Unless you are already in Ankara you might well have done what I did and that was to arrive in Ankara on the ‘High Speed’ Train from Istanbul earlier in the day. If you did then the train from Istanbul arrives in the enormous, new station. To get to the old station you take the bridge between the old and the new, just where people are having to go through a security check to get into the High Speed system, on the north-east of the new building.

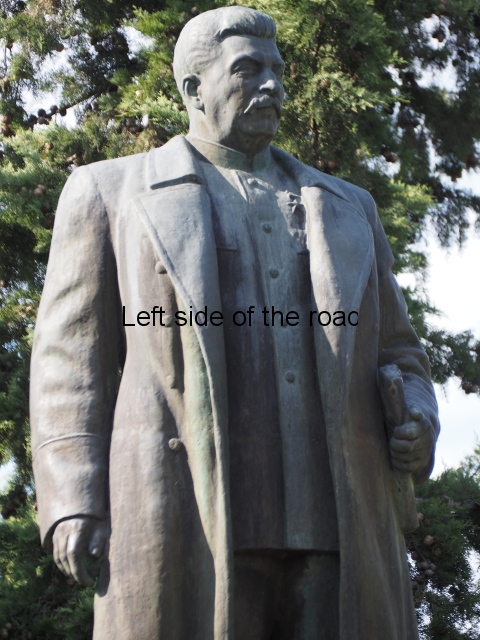

If you have plenty of time and are interested in Turkish Railway history you might want to visit the Railway Museum which is on Platform 1 of the old station. It’s open from 09.00-12.00 and then 13.00 to 17.00. I don’t know anything about it as I didn’t discover the place until after 17.00.

It’s on this platform (No. 1) that the Dogu Ekspresi leaves. On the day I made the journey the train pulled into the platform at 17.00 on the dot, a full hour before scheduled departure. There will always be a lot of people ready to get on the train at that time as most of the passengers will be travelling with a lot of luggage and there’s a ‘fight’ to find a space. This is bad enough in the couchettes, what it’s like in the seated accommodation I hate to think. Although there’s a separate baggage car very few people use it for their personal luggage – whether it’s even possible I’m not sure. But unless trains provide for what is happening everyday (that is, with more luggage space in the carriages) then the authorities should find some way to mitigate the chaos that proceeds every departure.

When the attendant comes to check just after departure you do not necessarily need a printed ticket. The two young lads in my compartment just gave their names and as they appeared on the system in that compartment that was sufficient. I offered my passport and that was enough.

An old carriage and a very new station in Ankara

The journey itself

The train left at 18.00 exact. My compartment was had its full complement on leaving Ankara, a old Turkish man (a couple of years older than myself, I later discovered) and two young students going to the University town of Erzurum (20 hours away) for the start of the academic year. Only one of the students had any real English and I had absolutely no Turkish – having been in the country for less than a week I hadn’t even mastered the basics of ‘please’ and ‘thank you’

This turned out to be one of those long train journeys where I had the privilege of being on the receiving end of local hospitality. Amongst all the luggage the older man had brought with him was a largish cardboard box. This was to provide sustenance to the four of us for the best part of a day.

Soon after departure, using an old piece of newspaper as a table cloth, he brought out some apples and oranges and after peeling them both with his pocket knife proceeded to pass the fruit around. I hadn’t pre-prepared anything and was just going to see what happened food and drink wise. As it worked out I didn’t need to do anything – although if I had brought something I could have least have added something to the party. (Perhaps by not doing so I was being somewhat selfish and not really getting into the spirit of things.) And he brought out more fruit as the evening wore on. After the beds had been prepared he asked, by sign language, if I wanted to eat but I refused. There was obviously more there than he would need himself.

His box came out just after midday on the second day for lunch – which also had more than enough to feed the four of us.

Food preparation for the journey

The two other young Turks didn’t seem to have prepared for the journey any better than me. Perhaps they were going to depend upon opportunities along the route, as I was. There was a basic restaurant section in one of the other carriages but it didn’t seem to have a wide selection, other than providing tea and coffee. As I didn’t need to I didn’t do much more than have a brief look at one time. I though they might have prepared some sort of breakfast but that wasn’t the case either.

Travelling in a country with a Muslim culture

A few minutes to 19.00 there was a short episode of confusion. I was asked to move from where I was sitting near to the door. I was initially reluctant to do so as I didn’t understand why. With a little bit of ‘explanation’ I eventually realised that the older man wanted to kneel on the seat I had been sitting on as this was the closest he could get in the carriage to facing east in order to pray. He turned his ordinary street hat back to front (simulating a skull cap) and proceeded to pray. The three of us left him to it. Me to look out the window the two young men to get their nicotine fix. (In theory there should be no smoking anywhere on the train but every end of carriage would have smokers there at regular intervals for the next 24 hours.)

He repeated this exercise at 20.00 and then I think it was some time in the early afternoon of the next day that he did so again – but that time I was watching the world go by through the windows in the corridor of the carriage.

Early to bed

Not long after leaving Ankara the attendant had distributed packs of bedding to every compartment. Unlike on some train networks it is the attendant who actually makes up the beds this is not the case on the Turkish Railways – the distribution (and later collection) of the bedding is as far as it goes. That’s not a problem apart from the fact that the design of the lower bunk was that it was supposed to be locked – by a large key which the attendant would hold – but as he played no part in the preparation for sleep that lock was permanently open. Not a real problem until the person next to you decided to use the arm rests to raise themselves – in the process throwing anyone else on that side forward. And however much this happened you would always forget the consequences of an unthought about movement.

Come 21.30, more or less, there was a move to prepare the beds and soon people were in their assigned areas. But by 22.00 I was only one who was not away in dreamland. From my experience an early night always seems to accompany overnight train travel.

Control of the light

I’m happy with that ‘early to bed’ culture. What it provides me with is the vital ‘control of the light’. And this is why travelling in the Pullman carriages would have been so unsatisfactory for me. In an overnight carriage with the internal lights on all you see is yourself and your neighbours. The outside world remains a mystery as the light pollution is so intense.

On the other hand if you can turn off all lights, with the compartment door closed, it’s as dark inside the carriage as it is outside, if not darker. So what you are passing becomes like a film where all that happens can be witnessed. Even the stars become visible – but not so much on the night I was travelling. This was one of the great joys of my time on the Trans-Siberian on the DPRK train.

These are the ideal circumstances in which to let your mind wander, watch whatever might be happening as you pass and let the effects of the raki (the last of which I had bought in Albania and which had been saved for this very moment) decide when you actually go to sleep.

Speed of the train

The train was pulled by a couple of twinned diesel locomotives – although the exact two changed a number of times during the course of the journey, probably every four to six hours, perhaps depending upon the terrain and the schedule they followed.

The power for the first part of the journey

But there were times, especially after everyone else crashed out, that the train was able to gather quite a speed on the plains. It was also able to do so on later parts of the journey the following day. But at times when going through the mountains the speed was little more than walking pace as it climbed whilst at the same time following a twisting route through the mountains.

However, by the end of the journey the average speed was, more or less, 50km/h.

Waking up

I might have been the last to go to sleep the night before but I was also the first to stir the next morning, just a little before 06.30. The last I remembered we were racing along, passing towns and small villages, but when I looked out the window in the morning we were in the mountains and the train was crawling along a twisting track that was also gradually climbing. At that time I measured our height at about 1,200m and continuing to climb

Breakfast

But I wasn’t the only one awake for long as the older Turk soon woke up and almost immediately pulled the cardboard box from under the seat and brought out bread, cheese, tomatoes and peppers – shook a carton of drinkable yogurt – and that was the meal we shared between us at about 07.00. It was a couple of hours before the young Turks stirred so as there was no real communication between us after finishing breakfast. We just sat there and watched the world go by.

A word about tomatoes

I’ve probably had more tomatoes during this most recent trip than at any equivalent period in the past. They appeared in the regular breakfasts on offer in both Albania and Turkey. That repetition could become boring if they were not such good tomatoes. Anyone who has had to suffer the excuses for tomatoes that are offered for sale in whatever outlet in Britain has forgotten what a good tomato looks and tastes like. They are rarely red and are devoid of any taste whatsoever. I might be taking Tesco to court over the Trades Description Act on my return.

A word about the sanitary conditions

Whereas on the train from Istanbul to Ankara there were the western toilets on this overnight train you have to deal with the squat version. Not a problem but it doesn’t get any easier when the train is moving.

The terrain

I think someone in Turkish Railways had put a bit of thought into the timetable for the departure of the Dogu Ekspresi, whether from Ankara or Kars. Departing Ankara at 18.00 means it is when people are waking that the train makes its way through the mountains and the more interesting scenery. For the next twelve hours that scenery changes but is still like a nature film with a never ending story. The scheduled arrival in Kars just after 18.00 means that the most advantage has been made of the light. Likewise the departure from Kars is at 08.00 (arriving in Ankara at 08.22 the next day) and so the most interesting landscapes are passed through in daylight. This will take a bit of a blow, in both directions, when the days get shorter in the winter but the timetable gives the best in all circumstances.

Fortunately it was a beautiful and bright sunny autumn morning on the second day of the journey. As the day wore on and as the train reached heights of more than 2,300 metres it was clear that autumn was setting in. At lower levels the trees were just on the turn whilst at the highest levels the leaves on some of the trees had already turned to a bright yellow.

But as is always the case in 21st century societies what you perceive as nature is the result of intervention on a massive scale. Turkey has experienced a rapid expansion in dam building in the last 10-15 years or so, both to ensure potable water supplies as well as for the generation of electricity through the construction of hydro power plants. These create lakes in the mountains where before there were just valleys and, no doubt, there have been more than a few villages lost in the process.

But autumn is before the rains of winter or the arrival of the snow melt from the high peaks in the spring so all the lakes were relatively low whilst not giving the impression that there was any water shortage as such. But it must have been a hot summer as all the land looked particularly parched and most of the agriculture seemed to rely on some form of artificial irrigation.

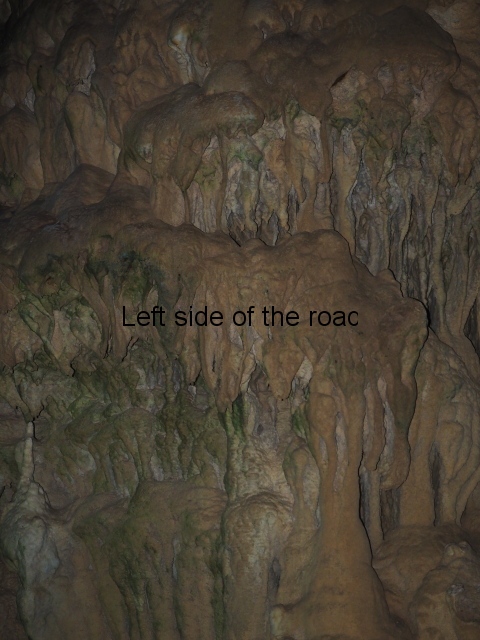

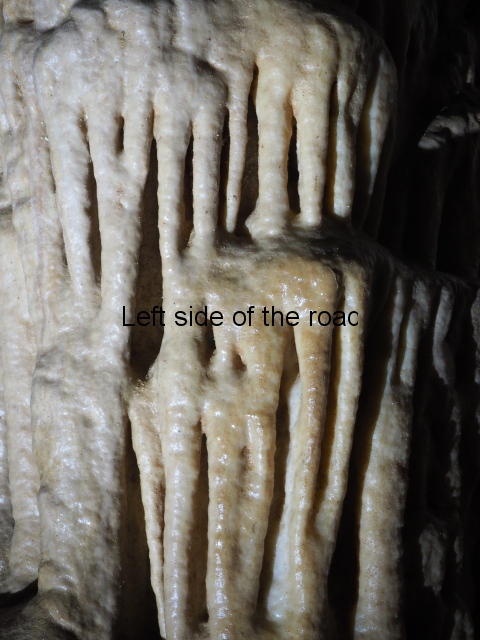

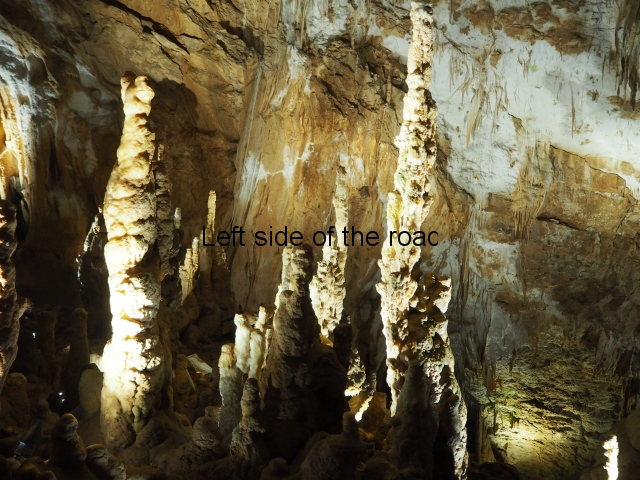

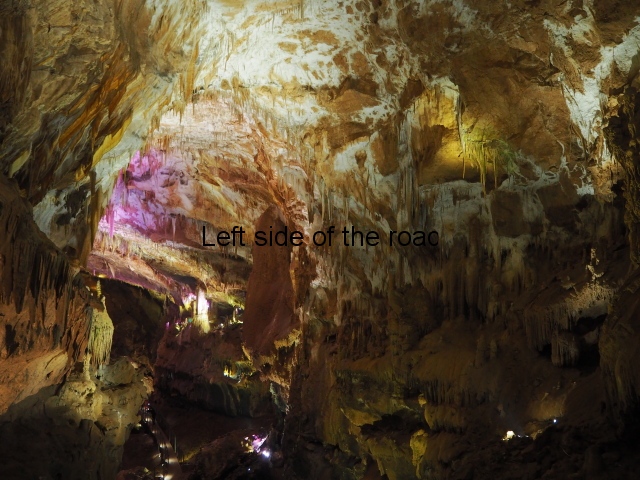

In the, roughly, 600kms of daylight on the second day the route was bound to take us past various rock formations and as the train moved steadily east we passed sandstone, limestone and then volcanic formations – even at one time, in the late afternoon, similar to those found at Cappadocia, but on a much lesser scale. We were also reminded that Turkey is still in an active and ever changing tectonic location and this could be seen by the way the layers of rock had been twisted and turned by the upward movement of the land.

When the train was crawling slowly through the narrow gorges you are reminded of the effort it takes to build these lines. Now machines can cut through mountains like a hot knife through butter but systems created in the late 19th and early 20th centuries depended upon sheer muscle power. This is evident out in the open but becomes even more so when passing through the innumerable tunnels that lie along the route – many of which took major turns in the dark.

In Turkey, at least at the moment, this huge amount of expended labour power is not going to waste, not like the criminal waste that can be seen in some other eastern European countries, notably Albania. However, even on this route there were signs that lack of investment in the rail infrastructure had led to the run down of certain services with abandoned rolling stock, bogies etc., beside the track in out of the way and isolated places and for no apparent reason – at least as far as I could see.

It’s really only on a train journey, especially when the train has to take it steady due to the difficult terrain, that you can appreciate what you are passing. Not only is it the lower speed of the train compared to road vehicles that helps in this but you are also much higher up and have panoramic windows from which to view the world as you pass through it. The journey from Istanbul-Ankara on the so-called ‘High Speed Train’ was exhilarating when it was topping 250km/h but the journey was more interesting when going slowly through the industrial areas or the mountain ranges between the two major Turkish cities.

For much of the journey the land in the countryside was dominated by arable cultivation – with the production of an incredible amount of maize being most evident. However the further east the train progressed the lower, presumably, the fertility of the land and then what was most evident were the huge herds of beef cattle – together with fields devoted to winter fodder for the animals.

These weren’t the size you would normally see further west but were on a scale, at times, which remind you of ‘Rawhide’ and Wagon Train’ – for those old enough to remember them on TV. And there seemed to be no restriction on where they could go, there being few fences or barriers to prevent them grazing either on wild vegetation or whatever was edible in a field where the crop had already been harvested. In fact, in the latter the passing through of the cattle had the effect of providing natural manure for the next year’s crop.

These large herds of cattle, whether communal or privately owned, also started to have a real visual effect on the small villages that the train was passing on an ever more regular basis. You could make out barns for winter shelter – this was now quite high ground and the winters would be severe – as well as huge piles of straw and hay covered with vast sheets of (mainly) blue plastic. This gave a very distinctive look to the villages at this time of year as preparations were being made to be able to confront and survive the long, cold and dark days of winter.

But that all seemed a long way away as I looked out at bright blue skies and the warmth of the sun coming through the window making for a very pleasant journey.

On my own

With the lack of a lingua franca inside the compartment, and after I had said I was going all the way to Kars, I was of the understanding that everyone else was as well. Also my poor knowledge of Turkish geography, and the fact that I didn’t have a good paper map (indispensable on any long train journey) I wasn’t aware that about 4 hours from the end of my journey was the large University town of Erzurum. As we were getting closer to the city my three travelling companions started to prepare for leaving – me standing there a little perplexed as I thought they were getting off the same station as me.

There weren’t that many station stops on this long journey. Two of them must have occurred overnight and the only other stop had been at about 10.30 that morning when the train stopped for about 15-20 minutes at Erzincan.

Destination Board – Dogu Ekspresi

Matters were clarified and we bid our farewells and I was left on my own – in fact there weren’t that many other people in my carriage after leaving Ersurum – and I assume the rest of the train. Although it was good to have the companionship of the three Turks all the way from Ankara it was now also good to have some time entirely to myself. The only ‘interruption’ being the attendant collecting the bedding from the night before.

Four or so hours later, about 15 minutes late, the trains pulled into the town of Kars, just as it was starting to get dark.

Carriage No 7 – and my home for 24 hours