Five Fallen Stars Rise Again – Dema Monument

The monument at Dema (Manastir), just outside of Saranda in southern Albania, to those who died in the war of liberation against Fascism returns to something close to its original condition.

One of the goals in my travels around Albania is to identify as many of the Communist monuments as I can and to record them photographically, fearing that they might disappear in the not too distant future. On previous visits I came across a number that had definitely been very badly treated, some with such violence if you didn’t know what you were looking at then you wouldn’t know it was a monument at all. I will return to this issue later, when I will look at the fate of these statues and monuments in the context of the whole country.

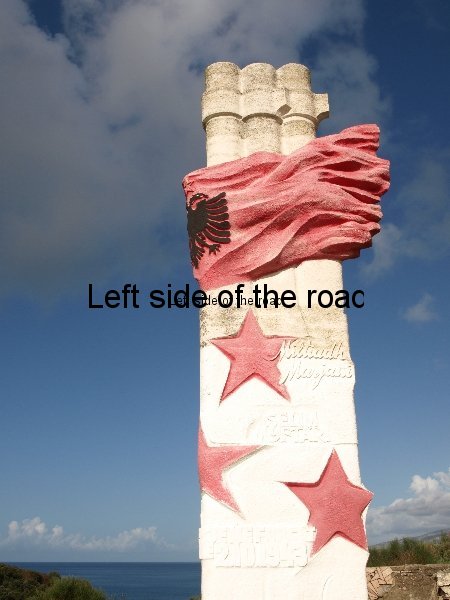

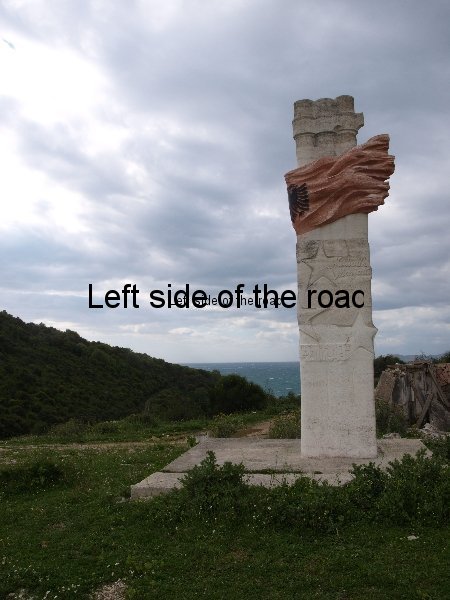

However, in the Saranda area I have noticed a dramatic change in the fate of one of these monuments, one that stands at a coll between Lake Butrint and the Ionian Sea. This can be seen along the road that leads from Saranda to the archaeological site of Butrint, just before passing through the town of Ksamil. I had seen, and photographed, this monument earlier in the year, in April. When I passed it a few days ago I noticed that it had been painted in the ensuing months and returned to photograph the newer version.

From the road it didn’t look like vandalism and that was indeed the case, what had happened was just the opposite and that someone had painted the five stars red. They were just white, like the rest of the pillar a few months ago. Now whether this was returning the monument to its original colour scheme I don’t know for certain, but that would make sense.

What has made the capitalists see red in Albania, is, in fact, the red. They have a problem with this. The flag of Albania, adopted in the country’s struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire (which celebrates its centenary on the 27th November coming) was the black double-headed eagle on a crimson background. Under Socialism the only change was to add a gold star, just above the heads of the bird.

This star has been the object of attack in a number of cases I have already seen, two of the most notable, and in many senses most public, being the erasure of the red star (which used to be behind the head of the central woman) from the huge mosaic on the façade of the National Historic Museum in Skanderbeg Square in Tirana, and the wall relief of a female Communist inside the Palace of Congress, also in Tirana.

Last April the flag was red, although not as deep a crimson as would have been the case in the past – I believe – but red nonetheless and it must had been touched up over the years. The subsequent painting of the five stars makes the monument much more distinctive, and also helps in telling the story of why the structure was constructed in the first place. Although I had studied the carvings before I had not made the connections which I now do.

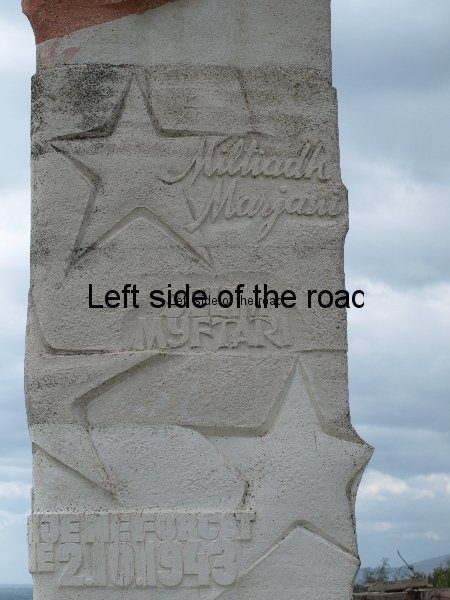

So why 5 stars? They represent 5 of the Communists who died in the war against Nazi Occupation. They are Miltiadh Marjani, Selim Myftar, Astrit Toto, Sadik Rusto and Niko Stefani and with my struggling with the Albanian language I believe they died at the hands of the fascist invaders on 2nd October 1943. As I took the pictures at the beginning of November it could well be that the stars were repainted in time for that anniversary (although there were no signs of any flowers, wreaths, etc., in the vicinity of the memorial.)

The text on the monument reads: Dëshmorëve që ranë këtu në përpjekje me forcat naziste më 2.10.1943. Astrit Toto, Sadik Rusto, Niko Stefani, Miltiadh Marjani, Selim Myftari. Which translates as: The martyrs who fell here against Nazi forces 10/02/1943. Astrit Toto, Sadik Ruston, Niko Stefani, Miltiadh Marjani, Selim Myftari.

So now their sacrifice is a little more obvious on their memorial and as once something is out on the internet it is there forever, this posting helps to keep the memory of the anti-fascists alive, especially at a time when the remains of the feudal warlord, despot, dictator, coward and thief, Ahmet Muhtar Bej Zogolli (the self-proclaimed King Zog I, Skanderbeg III) were brought back from France, where he died in exile in 1961, and deposited in a new tomb on 17th November 2012.

GPS:

N39.81197904

E20.01217

DMS:

39° 48′ 43.1245” N

20° 0′ 43.8120” E

Altitude: 35.7m