The stone mason from Borova

More on Albania …..

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Introduction

This short story was first published in New Albania No 5, 1976. It is reproduced as part of the effort to inform people of the cultural output of Albania during its Socialist period, following the concepts of Socialist Realism.

This particular short story also has a direct relevance to the sculptural lapidars of Albania. It’s a story about the events of July 6th 1943 when the Nazi invaders murdered all the inhabitants of the small village of Borova (in the south-east of the country) who weren’t able to escape and then burnt everything of use within the village.

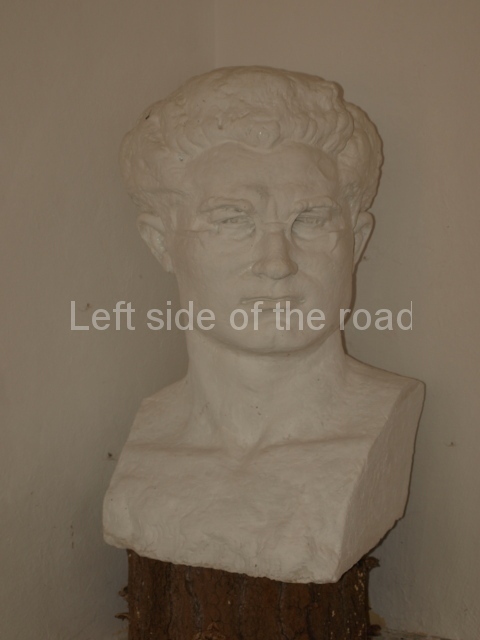

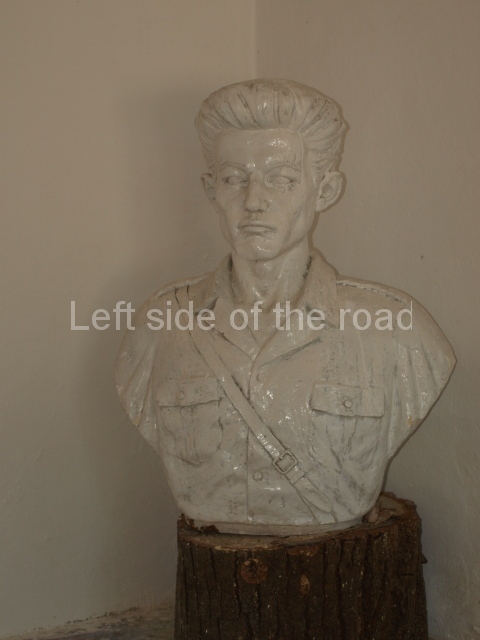

The statue of The Partisan and Child is part of the monument which commemorates that event.

This was part of the normal policy of the fascists as it followed an attack on a German convoy the day before in the mountains close to the village. This form of collective punishment is well known in examples such as Lidice in the (now) Czech Republic but they also occurred in those countries that were occupied by the Nazis, very often in similar retaliation to attacks upon the German Army by irregular Partisan forces.

By allowing the installation of the German Fascist Memorial in Tirana Park, after the collapse of Albanian society in the 1990s, the reactionary government of Sali Berisha displayed its contempt for the murder of its own citizens.

The stone mason from Borova

In memory of 107 Martyrs

by Naum Prifti

Many people wonder and cannot explain what urged Ligor to go to Borova that day. He took no heed either of the warnings of others or of the categoric order of the German command prohibiting the entry of civilians in to the still smouldering village.

Some say that Ligor went there because he was anxious to see what was left of his goods and chattels, whereas others say that he did so because he had had such a shock that he was unable to control his actions and, like a sleep-walker, he plodded through the streets filled with German soldiers between still smoking houses, without realizing what lay ahead. It happened that uncle Ligor was not in Borova on the day of the massacre. He had left the village early that morning taking with him, as usual, his bag with his hammer, trowel, and plumb line, and had gone to Novosel to build a wall. There is no trade in the world that requires fewer tools than that of the stone mason. Ligor was well aware of this because with that bag on his shoulder he had wandered for many years to different points of the northern hemisphere. His hammer had cracked the stones of three continents. He had worked at Khalkis, on both the beautiful shores of the Bosphorus, in the cities round the Black sea and, finally, he had crossed the Atlantic to try his luck in America. For this stone mason life had been hardship and toil everywhere. But finally Ligor had found some consolation in saying that this was due to the bad trade he had chosen. ‘That’s how it is with our trade,’ he would say, rubbing his hands on his coarse woollen trousers. ‘Wherever you go, you are dealing with stones and from them you have to earn your daily bread. But is it easy to bread from stones?’

In the end after his long wanderings abroad he returned to his village and made up his mind not to go away again no matter how things might turn out. Life had not smiled on him anywhere. Then where else would he be better off? In the dirty doss houses in Istanbul, in the damp of Odessa or the soot of Detroit where you cough up black mucus as though your lungs are filled with dye. Here at last he was in his own home, where in summer afternoons he could sit in the garden under the trees and watch the people pass by. His house was on a hill and from there he could get a very good view of both sections of the village.

He had built this house with his own hands after he had returned from abroad.

‘All my life I have built for others; now, on the eve of my old age. I’ll build a house for myself in which to rest my weary bones.’ And so he set to work and built a small house, thinking to himself that this would be the best and the only property that he would leave his children. They would remember him for a long time and then, if they were able, let them build a better and more beautiful house themselves.

For some years now he had been hard of hearing and instead of using his name others had nicknamed him ‘deafy.’ Ligor was not put out about it and admitted himself that ‘my ears fail, me, so shout because I can’t hear!’

Ligor said that this was due to sticking nails in his ears. Anyone, who has worked with momento stone masons knows this secret. When the nail won’t drive in the wood and there is no oil or lard at hand, they smear it with ear wax? The wax serves as a lubricant and the nail goes in with ease.

…That afternoon, while he was working, from the top of the scaffolding he saw a dense plume of smoke rising in the sky over his village.

‘What can this fire be?’ he said to himself, standing hammer in hand. He shaded his eyes with his free hand and tried to make out which section of the village it was coming from.

‘It must surely be the children burning the straw left in the sheds. Or is it St. Peter’s Day? How silly of me, St. Peter’s Day was a week ago whereas, today it is July 6! But may be the children have found some rubbish in a corner and have set fire to it.’ It had been the custom since ancient times to clean out the sheds at the end of June each year and burn the straw and chaff that had been left over from the past year, before putting in the new fodder. These bonfires were the joy the village children. They gathered at the village square or threshing floor, lit the fire and jumped through the mounting flames. According to an old belief, those who jumped over these fires burned the fleas left from the winter.

When he was a child, Ligor had done this, too. The memory of those days came back to him through the mists of the past, and he smiled. Was it sixty or seventy years ago?

‘However, this doesn’t look like a straw fire. The smoke from straw is white, while this is columns of grey and black. This looks as if a house or shed has caught fire. And how will they put it out in this hot weather!’

‘Some poor family,’ Ligor thought to himself, ‘It is they who meet with such misfortunes; it is their houses which burn so easily. It’s hell of a life!’

The fire seemed to come from near the stream and he tried to remember the houses there.

‘Well, what’s done is done!’ he said, ‘I’ll find out when I get back to the village. Now I must get to work to earn my wages.’

He took a trowel-full of mortar from the bucket and spread it on the wall, with quick, deft movements then stepped down from the scaffolding to select a cornerstone.

Like any mason who was master of his trade, he knew that the better the corner is built the longer the wall will stand. That’s the whole secret.

Back on the scaffolding with the cornerstone on his shoulder, he gaped in surprise. The smoke over Borova had become a dense cloud as if the whole stream were in flames.

‘What’s all this? What is happening.’

Instinctively his eyes turned to the hilltop, to his house half hidden by the trees in his orchard and his courtyard;

‘Izet, Izet! Leave that mortar and come up here a minute!’

A thin boy in a collarless shirt and red breeches made of the signal flags of the Italian army appeared on the ladder to the scaffold. Ever since his son had joined the partisans, Ligor had been compelled to hire another assistant.

‘What do you think is going on, son? Look over there towards Borova. It seems like a lot of smoke, or are my eyes deceiving me?’

Borova was not an hour’s walk away from Novosel and although it was daytime, the boy could make out the tongues of flame lapping the sky.

‘You’re right, boss, several houses are burning.’

The mason pursed his lips and stood thinking. His mind turned to his partisan son, and the war which was becoming fiercer.

‘Do those damned Germans intend to burn our village, too, as they burned Vodica? It’s possible. Then the houses of those whose sons have joined the partisans will not go unscathed.

How much toil it had cost him to build and complete that house! A whole lifetime! And the enemy might burn it and in a few hours everything he owned would be dust and ashes.

‘And they might do it,’ he said to himself. ‘You can’t expect any good from the enemy. My son was right.’ He recalled the conversation he had had with his son before he joined the partisans.

… It was on a Sunday. Father and son had been working in the garden planting out onions and, when they had finished and were washing their hands, his son had asked: ‘Father, have you a rifle hidden anywhere?’

Ligor shook the water from his hands and. from under his grey eyebrows, looked at his son in surprise.

‘I have wielded the hammer and have had no time to strut around with a rifle on my shoulder.’

‘Oh, I just asked in case you had one?’ ‘I have no rifle. If you need a hammer I can give you one’

His son hesitated to reply. Then he said slowly:

‘I thought of joining the partisans.’

His father looked him up and down and then, surprisingly, asked only:

‘When?’

‘Any day, now.’

‘Hm!’

Ligor had stood up face to face with his son.

‘Have you made up your mind to sneak away like many others or are you asking my permission?’

‘I have decided to go, but I don’t want to leave home without your permission Father, you understand, our country calls us …’ Ligor did not allow him to finish the sentence. He wiped his hands with his handkerchief, folded it, put it back in his pocket, and then said slowly:

‘Have you thought it over well?’

‘Yes, I have.’

‘Well, son, you have thought it over and had your say. Let me think it over as you have done and then I shall give you my reply.’

And after thinking about it all afternoon pacing around the house and darting quick glances on his son, in the evening he had called him aside and asked him:

‘Even if I don’t give my permission, you will go anyway, will you not?’

‘Yes!’ his son replied.

‘Good. But if I were in your place, I would have asked my father whether he had any right to stop me if a greater father had called me?’

‘You gave me no time. You said you would think it over and walked away,’ replied his son, red with embarrassment.

‘Had you said this to me, I would have been red with shame as you are now. Poverty is hard, it is bad, but bondage is worse. The hammer doesn’t seen to change this world, let’s hope the rifle will do it!’

And thus they had parted. Nearly four months had gone by since his son had taken up his rifle. Now and then he managed to come home by night, and Ligor’s heart leaped with joy to see his son happy, cheerful and optimistic as never, before. This was not just the joy that springs from youth alone, but from something deeper …

Ligor placed the cornerstone and lining it up with his eye from above and from the side, and tapped it lightly with the hammer to shift it a few millimetres inwards, as if to say, ‘that’s the right place for you, stay here and see how well-placed you are!’

‘Boss!’ called Izet catching him by the sleeve.

Like all those who are hard of hearing, Ligor Pandoja craned his head foreward and met Izet’s eyes.

‘I hear rifle shots. Listen!’

The stone mason puckered the muscles of his face as he strained to listen.

‘I hear nothing!’

‘I hear rifle and machine-gun shots!’

‘Rifle shots? Perhaps the partisans have attacked them.’

The fires were increasing quickly and now the black smoke formed a dense cloud over Borova. This cloud was growing bigger and blacker.

Ligor picked up another stone, but stood with it in his hand. His eyes were turned towards the village.

‘I can’t work. It’s no use.

He left the stone on the scaffolding, picked up the hammer, the trowel and the plumb bob and line, put them in his kit and stepped down the ladder.

‘I’m going to Borova.’

Thus he set out from Novosel to Borova when the cloud of smoke had cast a shadow over the valley and turned the whole sky black. He always walked at the same steady pace. The tools on his back rattled together. He was aware of the noise they made without hearing it, for he was used to it.

The smoke over Borova had become an enormous dense cloud as if the crater of a volcano had suddenly erupted and the setting sun cast the shadow of the smoke for several kilometres over the gravel stretching to the foot of Mount Gramos.

On the way he met the first refugees, his fellow villagers, who had managed to get away amidst the bullets and the fires.

A woman leading a child by the hand, her face deathly pale and wide staring eyes, still filled with terror, began to cross her hands and beat her head as if cursing both heaven and earth.

‘The German fascists burned our homes and killed the people! Ohlahlah! Words cannot describe what our eyes have seen!’

Her gestures were more eloquent than her words, while the child sat in a daze by her side. The woman turned towards Borova and began to shout and curse at the Nazis as if they were there before her: ‘May you and all you have be wiped out and turned to ashes! May you never reach your homes alive!

The woman seized the child by the hand and pressed on, not knowing where she was going. The child stumbled along as if half asleep.

Ligor stopped in the middle of the road. Other refugees were emerging from the creek and among them he caught sight of his wife and children.

‘They are safe!’ he said to himself relieved of the nightmare worry that he might have lost them. From their sketchy accounts, Ligor learned what had happened during those two hours in Borova.

The partisans had ambushed a motor convoy of the German Nazis, attacking them in the pass of Barmash. The Germans had turned back, taking their dead and wounded with them. The nearest village to the scene of the attack was Borova and the Nazis had decided to wreak retribution in the cruellest and most barbarous way. They had posted up some white sheets of paper near the bridge, they had attacked like mad dogs. What did those posters say? No one knew. They pronounced sentence of death on Borova. Squads of Nazi soldiers were deployed throughout the village. Shoot the people, burn the houses!

‘We would have been killed, too,’ said his wife, ‘but we escaped because we saw the Germans coming and got away through the back gate to the garden and down into the bed of the stream.

‘Did they set fire to the house?’

‘Yes!’ said his wife, ‘but who cares about the house. We are lucky to be alive.’

‘Where shall we go, where Will we find shelter when winter comes, what shall we do for food, for clothing ?’ All these questions crowded into Uncle Ligor’s mind and he shook his head in despair. Life had brought them to a very critical pass and there was no ray of hope to be seen anywhere.

That night he went to one of their friends in Novosel.

The host, as if he understood what was worrying Ligor, said:

‘Stay here with us until we win. What we have we shall share together.’

‘Thank you!’ said Ligor, ‘but these are not the times to be a burden on others. Everyone has his own problems nowadays.’

‘It’s in bad times you need a friend. And our boys are not fighting in vain. I tell you, the Germans are hard pressed; that’s why they are doing such things.’

Amidst the grief, uncertainty, and general distress the short July night seemed to drag on and on.

Next morning Ligor was up early as usual. Could that dozing, interrupted by moans, sobs, and sighs, be called sleep? The heartache, grief and anxiety abated through the night and in the morning it all seemed to belong to another time.

Ligor began to pace the room. Only the children were still asleep. He poked his head out of the window that looked towards the village. He could not sit still, and the idea that he should go to Borova, and see with his own eyes what had happened there, kept tormenting him.

In the end he made up his mind.

‘Turn back, Ligor,’ said his wife, ‘there is nothing to see. Borova has been destroyed. There’s nothing left but ruins and ashes!’

‘I’ll not turn back!’ said Ligor, and his wife, who knew him well, realized from his tone that he had decided and nothing would turn him from his course.

He had his bag with his hammer, trowel and plumb line on his back. His hearing was not good, but he was aware of their rattling because their melody was like a leitmotiv that had accompanied him all his life. Why had he taken his tools along? He himself did not know. Mostly from force of habit since he was used to walking with that small burden on his back.

Near the village, he met a group of people. They had set out to bury their dead relatives left lying in the roads and gardens, but the Nazis had not allowed this. They had threatened them with machine guns and had not allowed any one to enter the village. They told Uncle Ligor it was useless to try – ‘Better turn back before too late’ – but they could not convince him.

‘I set out for the village and that’s where I shall go.’

‘But they will kill you, Uncle Ligor!’

‘And why?’

His question was truly astonishing, but quite sincere and logical. Why should they kill an old man who was coming back to see his people, his village and his home?

The Nazis had condemned the village to extermination and they meant to carry the order out. However they did not stop Ligor. Why not? Because he entered Borova with an air of mastery, proud, head erect, disdaining them and entirely unperturbed.

Deafy walked between their vehicles without hesitation or fear, without even deigning to glance at them. He had seen any number of vehicles and armies in those far away countries and their appearance aroused not the slightest interest. Chest out and head erect, he walked firmly down the cobbled road with extraordinary calm and self-assurance. His steps were long and heavy, and echoed on the road. He made no attempt to hurry, to go away or to hide himself. He marched ahead steadily, proudly, like a man who has an important mission to perform, who assumes majesty from the importance of his task.

The German patrol opened the way to him and Ligor entered the village. He saw the burned houses, the blackened beams, the gables and foundations lying together and a knot seemed to gather in his chest. Near the bridge, on the walls around the springs and gardens he saw the posters. ‘These must be those white sheets of paper they told me about,’ he said to himself, paying them scant attention.

He left the highway and took the path towards the hilltop. The Germans were watching him from the road. According to them, this man could have nothing to do with the village. He must be some traveller who happened to pass this way.

Ligor stood in front of his house and looked it over carefully. The roof had fallen, the walls were blackened and the windows gaped empty. Some smoke was still trickling skywards from within the walls. A bitter, choking smoke. Everything had come to a sudden and unexpected end. The stones were blackened and split from the great heat. He knew every one of them, for he had laid them there with his own hands, and it seemed as if the stones knew him, too. Their gaping mouths spoke a language which the mason could understand.

He took the bag from his shoulder and walked around the house. Smoke, sorrow, silence.

Then he turned and looked over the village. The white walls, painted gates, windows with curtains and pot plants were no more Ruins, heaps of ashes and the bitter smell ol smoke that stung the eyes and throat.

From the bridge the Germans followed the movements of this man, who had walked up the hill and was surveying the village.

‘We’ve got to start from the beginning again,’ said Ligor, shaking his head. And, like a man, who knows what he is about, moved to one side, took off his jacket, folded it and laid it on the wall.

The July heat was scorching, the stones of the still smouldering houses and even the cobblestones were scorching, but more than all this he was burning with emotion.

His shirt gleamed white against the blackened walls and trees.

Ligor bent down and caressed the golden down on leaves of the tomato plants between his fingers, breathing the aroma. He loved this smell and it seemed as if he were eating fresh tomatoes. The tomatoes were still small, the size of hazelnuts and hidden among the leaves.

Then he lifted down his bag of tools, took out his hammer and trowel, rolled up his sleeves, and built an improvised scaffolding of some boxes and boards which were lying in the courtyard. He climbed on it and began to remove the ends of half-burned beams. In a little while, his hammer began to beat out the old song on the still hot stones.

The Nazis, who all this time had watched in stunned surprise, flared into anger. The challenge of this stone mason infuriated a German officer, and he ordered his soldiers to open fire.

Bullets began to fly towards the hilltop, whistling angrily through the trees, raising chips of stone and dust from the ground. They were tracer bullets which left behind a red, green or blue line. Ligor saw these missiles which flew by like so many brilliantly coloured butterflies and he was pleased. He did not hear the shots, seeing only the coloured lines the bullets left behind in the air, and he was astonished for it was something he had never seen before. ‘What are all these butterflies?’ he wondered, for he knew nothing of the new inventions in war equipment.

The bullets seemed afraid and avoided him. They flew past, through his clothes, beside him, in front of and behind him. He was like a target which could not be hit.

Then the mason thought he would make a little mortar and water his tomatoes and lettuces. So he went to the brook to fill a bucket with water. On the way back the Germans all fired one after the other, and a bullet punctured a hole in the bucket. The water began to spurt out from each side. ‘What’s happening to me today?’ he murmured to himself, ‘I don’t understand. This seemed a good bucket that didn’t leak. Or may be it was like this and I hadn’t noticed it.’

He bent down, gathered some leaves, rolled them in a wad and plugged the holes from which the water was flowing.

From the side of the bridge came a shout of relief for they thought that they had killed him, but Ligor Pandoja stood up again and walked towards the garden.

Orders, curses and shouts in German were heard, but not by the stone mason, and even if he had heard he would not have given them any importance, for he would not have believed they had anything to do with him. And Uncle Ligor walked on with the bucket in his hand up to the moment they knocked him down.

From his garden, wherever you turn your eyes, you see only mountains. Ligor saw the mountains for the last time that July afternoon. They seemed to waver, to rise higher than they were, to sink down, become misty, and be lost to sight. Then they emerged again clear and still. The vision of the mountains remained fixed fast on Ligor’s retina, and he did not close his eyes because he wanted to preserve their image forever.

The breeze rustled the grass, the leaves, the tender twigs, and sprinkled his white shirt with the pollen of flowers.

More on Albania …..

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told