Spring No 6 – Entrance

More on the Republic of Georgia

Spring No. 6 – Tskaltubo

There’s no shadow of a doubt that Spring No. 6 is the most impressive of the Soviet era bath houses in the Central Park of Tskaltubo – the spa town less than 10km from the second largest (now) city of Kutaisi. This was the particular spa Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, used to visit on regular occasions both before and after the Great Patriotic War. Up to the demise of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s there were more than 20 spa locations and/or hotels with spa facilities in and around the central park. Fortunately, to this day – after a recent restoration (by a private company called Balneoresort) – it still stands out as a special building.

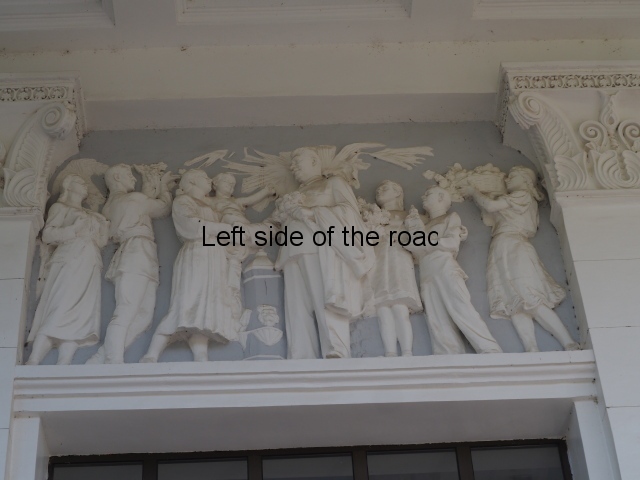

Its neoclassical frontage and the entrance hall is what makes it so special. Corinthian columns support a classic Greek inspired portico but what makes it really special is the frieze high above the entrance on the interior of the portico. By the age of Uncle Joe and the other images included in this bas relief it would indicate it was created after the Great Patriotic War when the buildings in Tskaltubo reverted from being hospitals to their original use as health spas for Soviet workers and peasants.

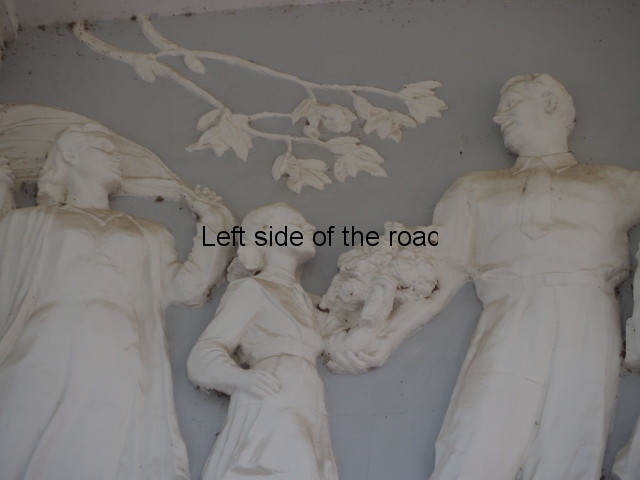

The ‘Welcoming Uncle Joe’ frieze

This frieze is in three parts and depicts the arrival of Joseph Stalin in the town and the welcome he is being given by either local people or other visitors, like himself, from the rest of the Soviet Union.

Spring No 6 – Welcoming Comrade Stalin

The central panel

In the central panel an avuncular Joe (in the last ten years of his life) is shown in a left profile. He is dressed in what was becoming his normal garb of a dress suit of a Marshal of the Soviet Union following his role in the defeat of the Nazi invaders, murderers and aggressors. (I accept there’s a problem with the development of ranks and medals/honours within the Red Army and would like to address this issue at some time in the future – but time is limited here.)

Over his left arm is his (again) traditional overcoat and in his left hand he holds a bouquet of flowers which have just been presented to him. He is smiling and looking towards a woman with whom he is shaking hands. She is probably part of an official welcoming committee. Whilst she shakes Joe’s right hand with hers’ she cradles a young child (can’t determine the gender) in the crook of her left arm. The child is facing us and s/he extends his/her right arm around the neck of the woman – presumably the mother. The child’s left arm is extended towards the General Secretary, thereby acting as a conduit, establishing a unity between the woman and Joe. The child is relaxed and smiling, as are the two central characters.

Between Joe and the woman, and underneath their clasped hands, is a drinking fountain – suggesting the healing quality of the local waters of Tskaltubo. On each of the two sides visible of the pillar are a face and a cup of a fountain.

Behind Comrade Stalin are two young people, a girl and a boy. She is closest to Joe and holds another, larger bouquet of flowers in her right hand. The boy, slightly further back, is carefully cradling in both his hands something that looks like a ceramic tower (perhaps to be presented to the visitor) This is, perhaps, a symbol of the town (but it’s difficult to say as it’s indistinct from ground level). The girl has her left arm behind the boy and seems to be encouraging him to come forward and meet the great leader of the working class.

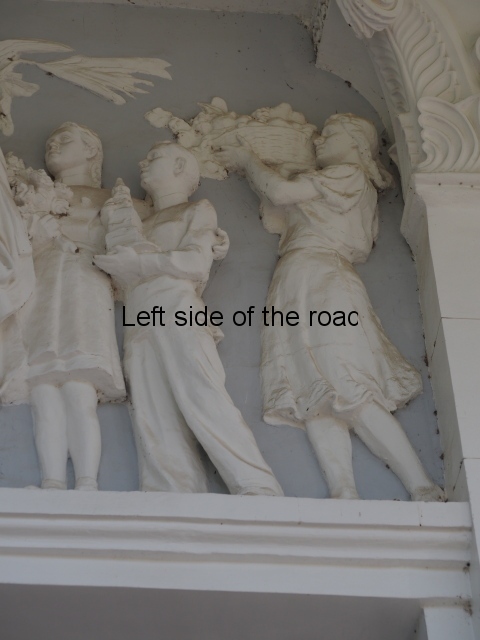

Behind these two younger children is an older girl holding a large basket of fruit, at shoulder height, which she is bringing to present to the honoured visitor. The three children are in contemporary dress. i.e., late 1940s early 1950s and are in left profile.

Behind the woman and child greeting the General Secretary is a man and a woman. He seems to be dressed in more traditional clothing from Georgia and holds high another gift to the visitor from Moscow. This looks like a cornucopia of grapes, representing the grape and wine culture of the region/state. I can’ make out what the woman at the rear is bringing. She seems to be clutching a couple of items to her chest. They are in right profile and they seem to be wearing traditional peasant dress of the region.

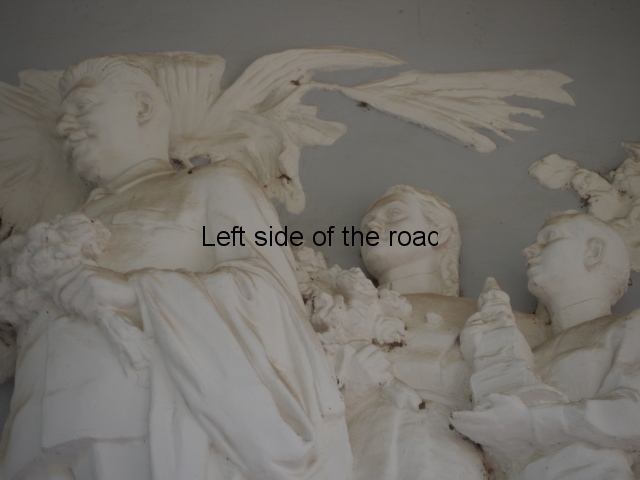

On the wall behind Joe, and appearing in a couple of other places behind the other characters, are white/cream markings. These perhaps represent a fluttering flag but the overall impression is somewhat confusing. The more I look at it the more I get the impression it’s a disintegrating halo – which is a little disturbing if that was the intention.

Spring 6 – Welcoming Comrade Stalin – right hand panel

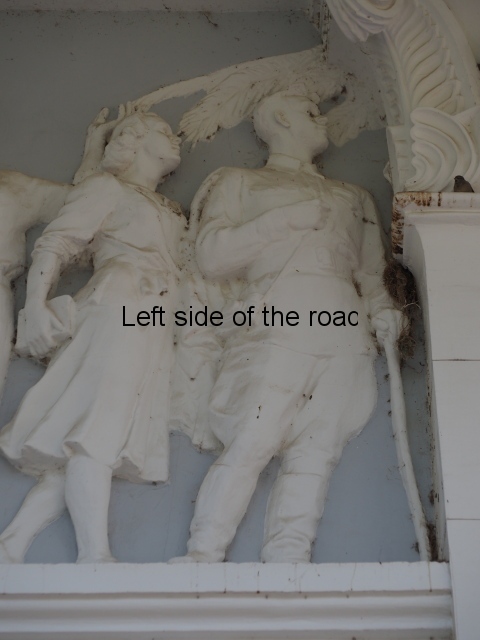

The right hand panel

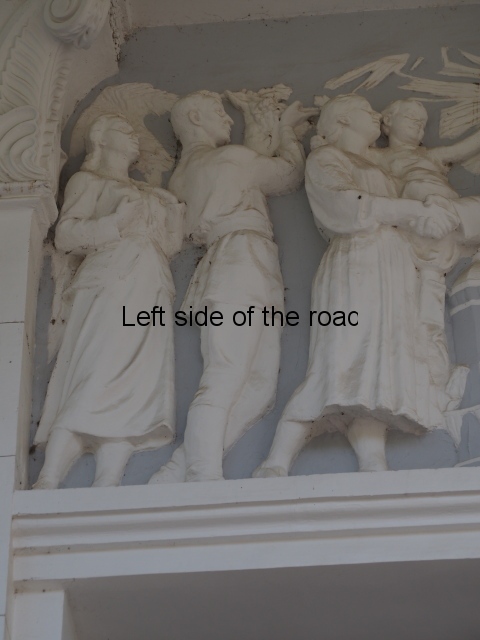

On the right hand panel we have a continuation of the procession wanting to meet the leader. At the front is an older couple. She seems to be holding another bunch of flowers and he, much more frail and needing support, has his left on her left shoulder and in his right hand (which we can’t see) he is holding a walking stick – part of which we can see. This would seem to reference the healing claims of the spa resort.

Next is a young sailor – and I don’t really understand this reference. We are talking about only a few years after the most devastating war the country had ever had to encounter. Yet he looks young and healthy. Therefore, why is he depicted? Beside him is a very young girl, five or six, who has another bouquet of flowers but seems to be pleading with the sailor, presumably her father, for something. She is really close to him, pressing against his leg, and he has his left arm protectively resting on the top of her back.

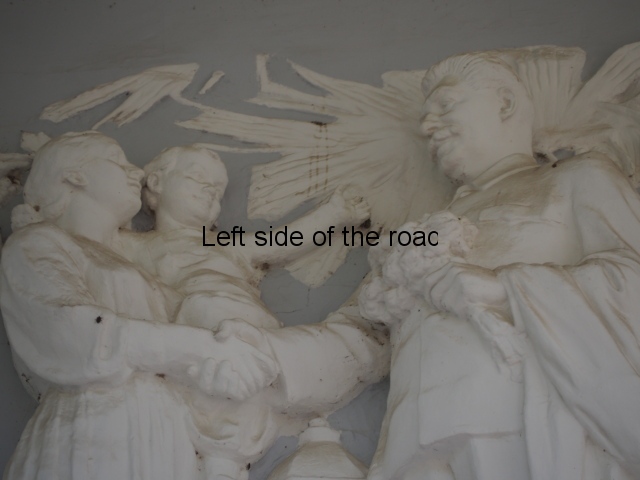

The final individuals in this panel are a couple of newly weds. They are hand in hand and rushing to meet Stalin. He is dressed in a formal suit and she seems to be dressed in the traditional attire of a Georgian bride of the time. (Now you can’t move in present day Georgia for ‘desirable’ western style wedding dress shops – almost certainly with a price tag which inversely matches the lack of sophistication of the design.) He holds high, in his right hand the certificate of their marriage and he seems to be asking for some sort of blessing from the leader of the Communist Party. It takes a long time to eliminate these practices of getting some sort of secondary justification from a ‘superior’ entity. I don’t like the depiction of this in a Socialist Realist piece of art work but it probably represented the feeling of the time and its depiction confirms a reality without providing a way forward. In her left hand the bride is carrying what looks like a book, what and why I have no idea

Above the couple are vine stems/leaves as a sign of fertility. Yet again, another throw back to feudal superstition. As I’ve suggested in other posts on Socialist Realist Art we are still a long way from throwing off the old traditions and thinking and that comes across in the art produced – even during those few years of Socialist construction.

Spring No 6 – Welcoming Comrade Stalin – left hand panel

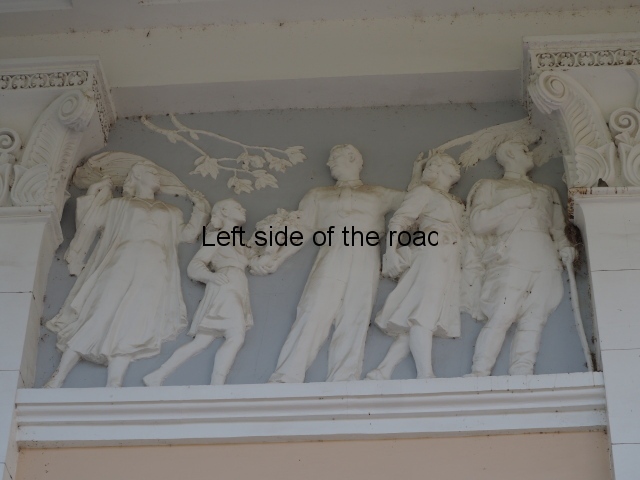

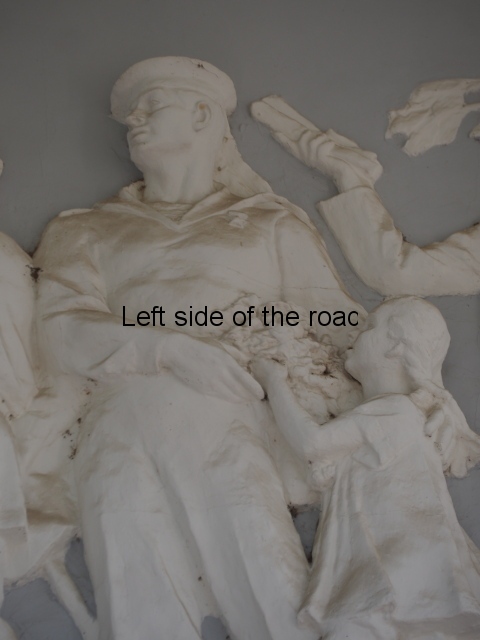

The left hand panel

The left hand panel contains five characters. Closest to the centre is a young, wounded Red Army man, in uniform. He has no obvious disability but he does have a walking stick in his left had to provide him with some sort of support. An interesting little bit of detail is that he has a camera on a strap over his left shoulder, his right hand under the strap at his chest with the camera resting on his right hip. This is possibly a Zenit or a Zorki, 35mm SLR, a huge number of which were produced after the Great Patriotic War.

Behind him is a young woman with her left hand on his right shoulder. She seems to be looking beyond him as if she were in a crowd of people wanting to get a glimpse of the visiting hero. Perhaps she is using his shoulder to allow her to get a slightly higher view of the proceedings. She is dressed in late 1940s clothing and her hair style is also from that period. She is also carrying a book in her right hand so a pattern seems to be developing here. Both of them are in right profile.

Behind the heads of this couple are what look like palm branches coming from above. They are similar to what we find in the central panel but there the leaves are totally chaotic, here more recognisable.

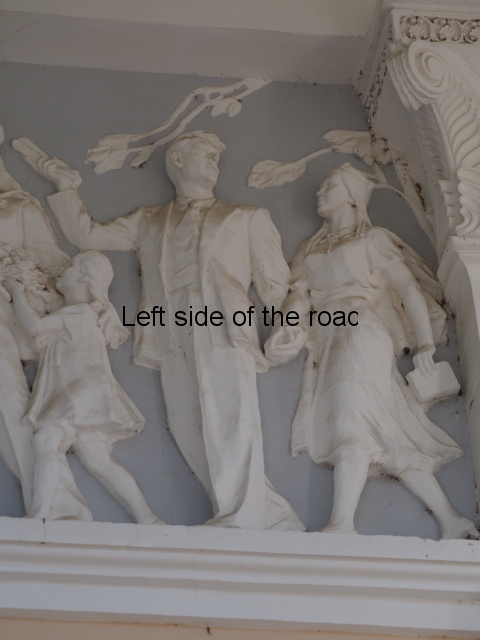

Next is an older man, dressed in contemporary 1940s semi-casual dress – he wears a tie but not a jacket. Unlike all the other characters in this story he is not looking in the direction of Uncle Joe. He is in left profile as he is looking back to others of his family who have come to greet the visitor from Moscow. His left arm is high above his head as if pointing in the direction of all the activity. He seems to be encouraging those behind him to hurry up and is pointing to where everything is happening.

His right hand is supporting the left elbow of a young girl who holds yet another large bouquet of flowers. She has her long hair tied back over the nape of her neck, her right hand on her hip and around her neck is a scarf which indicates that she is a Young Pioneer and is dressed in the uniform of the organisation. Her stance is as if she were running. In fact there is a feeling of movement in the depiction of this small family group which is completed by the presence of an older woman who is holding a banner, which is billowing out behind her, in both her hands. This presumably is the banner of the Georgian People’s Republic but any such detail is impossible to make out.

Above the heads of this last group a couple of branches of a vine come down from above, indicating the production of wine in the area.

I’m sure that many of those who enter the building are not really aware of the decoration that sits above their heads. With perhaps a few exceptions (those part of the building that have not yet had a major make-over) the only other part of the building that is interesting for its Soviet past is the main entrance hall.

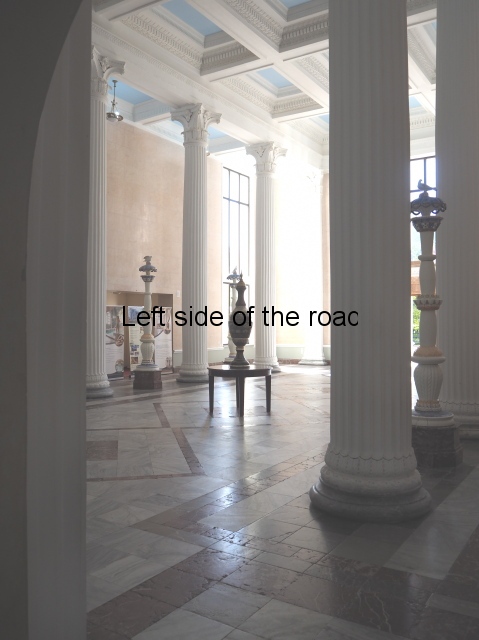

The entrance hall of Spring No 6

In the renovation of the building it was fortunately decided to try to maintain the impression those thousands that had entered the building over the years would have experienced.

The impression of space;

Spring No. 6 – Entrance Hall

the high ceiling;

Spring No. 6 – Entrance Hall ceiling

the magnificent commemorative urn (more details of which will be published shortly) in the middle of the floor – with an interesting clock on the wall behind;

Spring No 6 – Commemorative Urn and clock

The tall ceramic lamp standards;

Spring No 6 – Ceramic light

and the two, small stained glass windows;

Spring No. 6 – stained glass 01

Spring No. 6 – stained glass 02

The rest of the building

Spring No 6 is a huge building and won’t be getting anything like the number of visitors that it used to receive in the heydays of the 1980s and before. On my visits there were only a handful of people and that would indicate that the renovation that has taken place would not have covered the whole of the building – there would have been no chance to make any significant return on the investment – unless it was all part of a money laundering exercise.

The ‘renovation’ I saw was basically a total destruction of the original interior and the replacement by what would be found in a new build for the same purpose. That’s a shame as I’m sure the baths and rooms used for all the other services would have been tiled and decorated in an even more ornate manner that what can be seen in the abandoned and derelict spas that lie in ruins in the Central Park and surrounds.

So far I have been able to visit one very small part of the building that has undergone minimal ‘restoration/renovation’. That was the room I was told was ‘Stalin’s private bath house’.

But it is a working spa and there are a number of treatments that can be tried. One of the reasons there are few visitors now is that, for Georgians, any visit to the spas are very much a luxury and the foreign tourists who visit the country (and could afford it) might not be prepared to spend a couple of hours getting cleansed, pummelled and covered in mud.

An introduction to some of the treatments available will appear soon.

The driveway into Spring No 6

The main entrance to Spring No 6 is part of the public Central Park in Tskaltubo and there’s no strict dividing line between where the private and public meet. However, as part of the original project of Spring no 6 a large fountain – with a statue from Georgian mythology – was included. This is also worthy of a look.

Spring No. 6 – Fountain

Location

Spring No. 6 is in the northern part of Tskaltubo’s Central Park, about a ten minute walk from the present day market in the centre of town.

GPS

42.3223

42.5989

How to get to Tskaltubo

Marshrutka number 30 leaves from its terminus on the western side of the Red Bridge, which crosses the Rioni River beside the main Kutaisi market. Closer to the market is the stop for a number of buses but you walk through that area (passing a cheap out door bar on the right) to cross the red painted iron bridge. The marshrutka will be on the left once on the other side. They leave roughly every 20 minutes. Cost GEL 1.20 (not the GEL 2 as in some guide books – although some of the drivers will take the GEL 2 and say nothing although others are honest). The price will be on a piece of paper somewhere, normally at the front of the vehicle.

Journey takes about 30 minutes to get to the centre of Tskaltubo. Once you cross the railway track (after 20 or so minutes) you are at the bottom end of Central Park. The marshrutka then follows Rustaveli Street on the eastern edge of the park passing the railway station and information office, the Municipality, Court and Police buildings, and then the entrance to the huge (now luxury 5 star) Tskaltubo Spa Resort all on the right. (The marshrutka takes the same route when going back to Kutaisi and can just be flagged down anywhere along this road.)

When you get to the northern edge of the park the road widens out and after passing the Sports Palace on the left and the now being renovated (although seemed stalled to me) huge Shakhtar Sanatorium on the right the marshrutka heads up to the main market. Get off when the bus turns right at the corner by the ugly, modern Sataplia Hotel. This is where you would look for another marshrutka if you wanted to go to the Prometheus Cave.

To get to Central Park go back along Tseretseli Street (not the road you came up), pass the mural of the telecommunication workers on your left and head down to a very wide road junction. Cross this wide expanse of tarmac towards an arch and at the open space at the top end of the park head south and pass by the right hand side of Spring No. 3. Continue south until you reach the white, side wall of Spring No. 6. The entrance is on the west side of the building.

Alternatively (if arriving by marshrutka) you could get off at the main entrance to the Tskaltubo Spa Resort and walk towards the back of Spring No. 6 through the park.

More on the Republic of Georgia