More on the ‘Revolutionary Year’

November 11th – Armistice Day

The first commemoration of Armistice Day in Britain took place on November 11th 1919. In order to get men to fight in the new style of warfare brought about by the start of hostilities in 1914 what was euphemistically called ‘the Great War’ by the British was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. With that as a background it made some sense to remember those who had died fighting for the interests of their respective imperialist countries. However, since the 20 million estimated to have been killed between 1914 and 1918 paled into insignificance in the century following that conflict the whole ethos of the day has changed.

Once the ink was dry on the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 29th June 1919, cities, towns and villages in Britain, France and Belgium (but not in Germany who had other matters – like starvation, an attempt at revolution and the rise of fascism – to concentrate the minds of the people following the draconian conditions of the ‘treaty’) made efforts to raise money so that those who died could be remembered in those places they lived before being shipped off to the trenches of the Western Front or other theatres of war. (The discrepancy about the dates you’ll see on such memorials stems from whether 1918 – which was the year of the end of the shooting – or 1919 – the year of the final treaty – had been chosen as the time when the war ended.)

Even the latter date might not have been totally accurate as the so-called ‘allied intervention’ in the Russian Civil War following the October Revolution – where 14 nations that had been trying to destroy each others’ armies and navies got together in an attempt to destroy the first workers state – continued until 1920. British fatalities in that conflict were, no doubt, listed on the local memorials to appear throughout the twenties although they were fighting in a completely different theatre of war and for completely different reasons.

So even before discussions on the treaty to end the war ‘to end all wars’ had even begun British forces were following the old imperialist road of killing all those who might challenge the right of capitalism to rule the world for the benefit of a few.

Added to that far off conflict the echoes of the guns on the Western Front had barely faded before those psychopaths from the British Army, who hadn’t had their fill of blood, volunteered to join the Black and Tans (the British equivalent of the proto-fascist Freikorps of Germany) who murdered with impunity in Ireland, when the Republican movement was a bit more principled than it is today.

When Nazi forces murdered without discretion, in various countries, during the Second World War the perpetrators were branded as war criminals. When the Black and Tans did the very same in Ireland between 1920 and 1922 they were commended as heroes fighting for the British State. Presumably those that were killed by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in the Irish War of Independence are also commemorated on the World War One memorials, if not by having their names recorded at least by association with the recently concluded war.

As time went on, and not too many years at that, the emphasis of ending wars as they were too destructive, in terms of personal suffering as well as the destruction of what a society had already created, was being pushed into the background.

My point here is that the idea behind Armistice Day, November 11th had become a lie, even before it could be first commemorated.

People in Britain seem to have an unhealthy appetite for celebrating war anniversaries. It was in just such a climate that the decision was made to make a big issue out of the centenary of the First World War – I could accept (just) commemorating the centenary of the end of the war in 2018 but the beginning in 2014? That’s just bizarre. But here the politicians are being clever. They know that there’s a deep-seated jingoism in a sizeable proportion of the British electorate that they can tap into. They also know that those very same people aren’t prepared to be critical of what has happened in the past – especially if the British ‘won’.

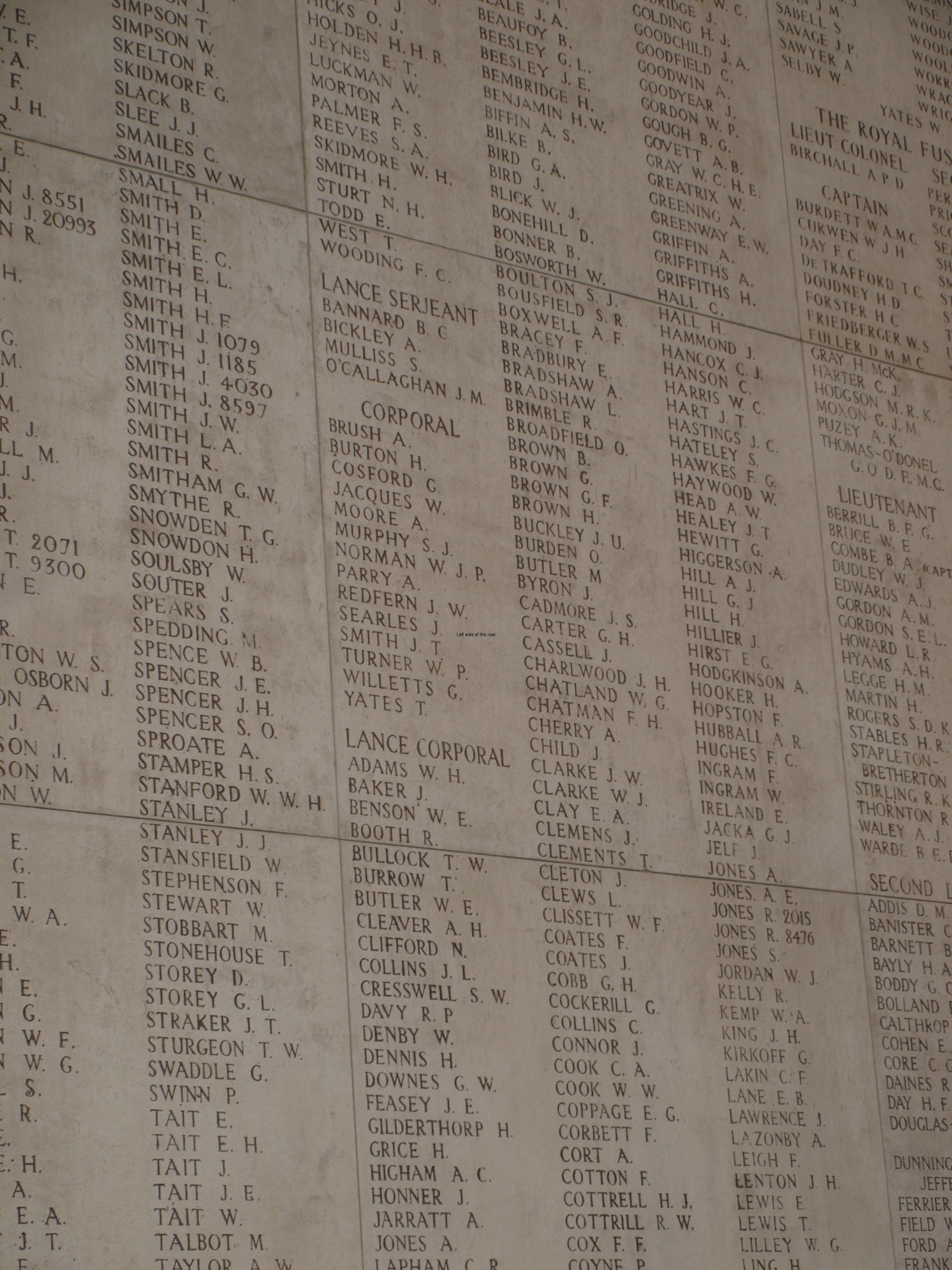

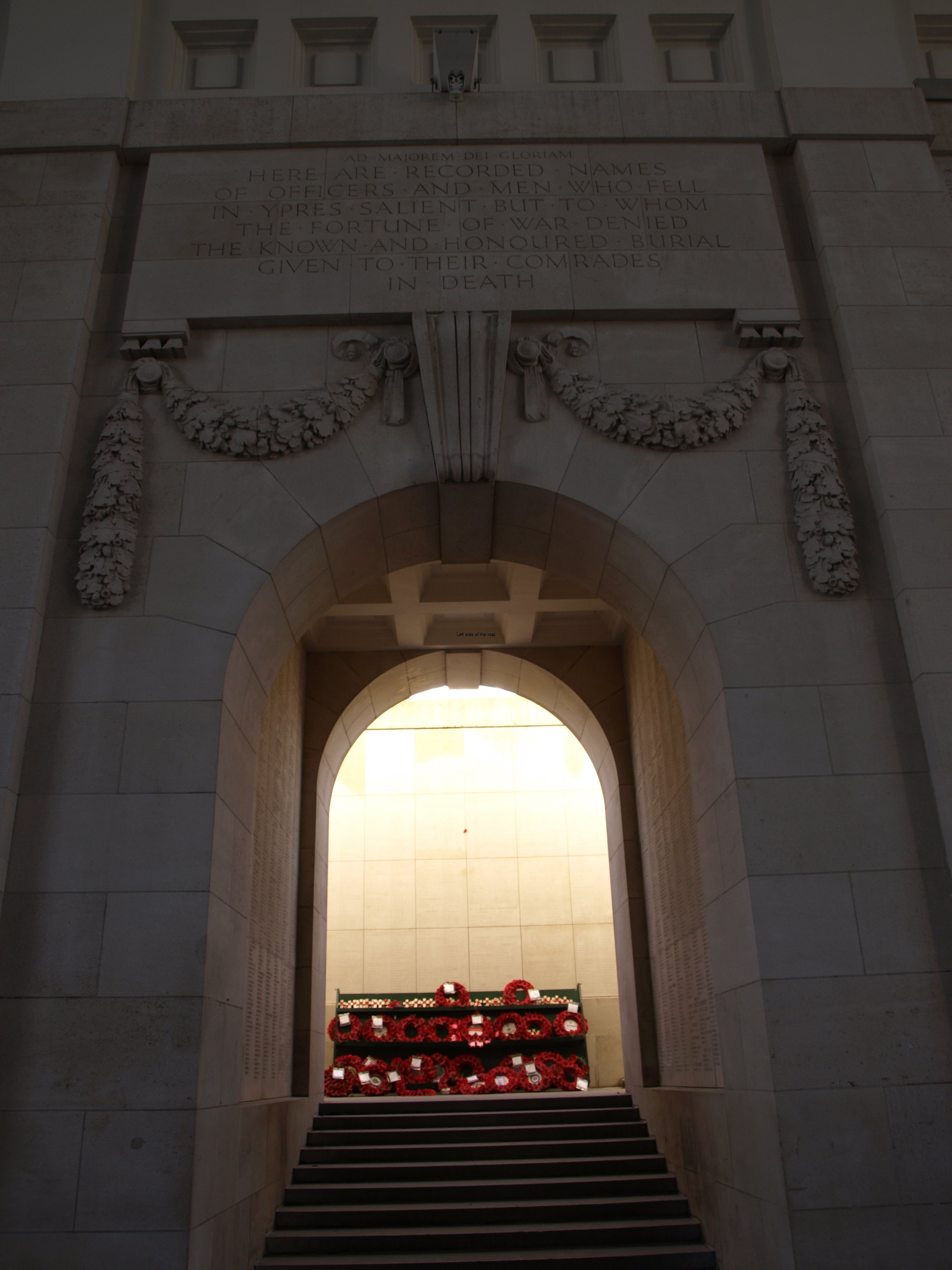

We have already seen a lot being made of the 1914 ‘Christmas Truce’ and no doubt tours to the battlefields of the Western Front and the likes of the Menin Gate in Ypres have been selling like hotcakes but are we really dealing with the real issues at hand?

Although this particular ‘celebration’ was initiated by the Tories and the ersatz Tories of the liberal Party such pandering to the lowest political level is also a forte of the Labour Party. Through the centuries when the British armed forces had been killing, raping and looting throughout the world (of the 196 countries in the world today the British have NOT invaded only 22 of them) there had been no proposal of a day where those forces were celebrated – this was probably because even those in power at the time realised that making these killers out to be heroes would be tantamount to making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

So, if after so many years without a special day devoted to those who had fought and/or died in past conflicts, why did the Labour Party introduce Veteran’s Day in 2006 (3 years later to be called Armed Forces Day)? Because British forces were becoming even more deeply involved in a continuous series of futile, un-winnable, unpopular and more than probably illegal (on their own terms of reference) conflicts which are likely to go on for ‘a generation’. What better to throw in a parade every year and people can forget reality. It also makes it difficult for those who oppose such imperialistic shows of military might as they will be branded as being un-supportive of ‘our boys – and now girls – who are fighting for ‘us’.

Whenever I hear this type of ‘argument’ I always wonder how it would be received if it came from the mouths of the parents of German Waffren SS soldiers whose idea of fighting for ‘us’ was murdering all the villagers and burning every building, as they did in Borove in Albania, or corralling every villager they could into a large building and then setting it on fire, burning all of them alive, as happened in hundreds of villages in the Soviet Union during the Second World War.

There was a sound moral reason why ordinary people (not the ruling class) of Britain adopted the idea of a day to remember those who had died in the First World War. Of course, many had died in previous wars but, in numerous senses, the war that began in 1914 was different. Although for the first year or so the war was conducted by ‘professionals’ they were soon joined by ‘volunteers’ and when that wasn’t enough to feed Death’s insatiable appetite mass conscription was introduced for the first time in 1916. These were children in many ways. Whether from the factories or the farms the vast majority of them hadn’t gone much more than a few miles from the place of their birth before being shipped off to some ‘exotic’ location. They took much of the propaganda fed to them uncritically and therefore were like lambs to the slaughter.

Any leadership was denied them when the traitorous Labour Party (yes, it’s been betraying the workers from the earliest days of its existence) decided to go back on the decisions made at gatherings, in the years leading up to the war, in such declarations as the Stuttgart Resolution (1907) and the Basel Manifesto (1912) – which called upon workers not to fight in a bosses war – of the Second International.

Although there had been many casualties in previous wars the overwhelming majority of those from the ‘Great War’ were young men in their late teens and early twenties. This had a not before experienced effect on women who never got closer to the war than those living on the south coast hearing gun fire from across the Channel. For, more or less, each soldier who didn’t return there was a young woman who had little or no prospect of marriage (at a time when this was the norm in society) or experienced widowhood . And this doesn’t take into account the many more who did return but with severe physical disabilities and even more who fought the war every day for the rest of their lives due to the trauma suffered in the trenches.

In Britain the civilian population didn’t suffer in the same way as they did in France and Belgium during the actual fighting. The real suffering followed 1918 and that made Armistice Day commemorations much more meaningful for many more people in the 1920s. This was unprecedented and hasn’t really been repeated in any way close in Britain since (although other countries had to face a similar situation subsequently, most notably the Soviet Union in the Great Patriotic War).

This should have been a wake up call to British workers. It wasn’t, even with all the suffering caused, both economically and socially, in the 20s and 30s. Even though the conditions showed that the capitalist system offered nothing to the majority of the population the British working class weren’t prepared to go that step further and confine it to the dustbin of history. The working class were responsible for this but then they weren’t able to create in their midst a revolutionary party that would be able to lead such a struggle – not then, nor since.

Although the Treaty of Versailles officially ended the 1914-19 war that was only really a declaration that called for a time out. The war might have ‘ended’ but the same issues that caused the war in the first place remained. Those issues could have been resolved if the workers of Europe had stood firm with the young socialist state in the Soviet Union and changed their own countries but, for various reasons, they didn’t. The rise of fascism generally, the victorious coup carried out by Mussolini in Italy, the defeat of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and, especially, the rise of Hitlerite Nazism in Germany made the World War, Part 2, inevitable.

The war in which British forces fought between 1939 and 1945 can safely be said to have been the only ‘just war’ in the history of the country. It was an ideological war for many of the soldiers involved (despite the overarching agenda of the politicians and those capitalists they really represented) with the defeat of fascism being the prime aim. For those who fought the gaining of land, resources and materials for the capitalist class was never an issue, unlike the majority of previous incursions abroad. (This is excepting, as it was fought solely on British soil, the English Civil War of the 17th century where the people rose up in a national liberation war against the God-crazed despot and dictator Charles Stuart.)

When that war officially ended in August 1945 that should have been the point when the world could have said that it had gone through the war to end all wars. But again it wasn’t. The enemy of the war that had been won, in great part, by the unimaginable sacrifice of the Soviet people, changed. Expansionist German had finally been defeated but that didn’t mean that the new kid on the block, the United States of America – together with its already tethered and dependent poodles, the United Kingdom and the other western European nations – hadn’t picked up the baton for world domination. The country which had fought fascism, as one of the ‘allies’, was now the enemy and communists seeking to make a world without war had to be defeated at all costs.

The British Armed Forces were to played, and play to this day, an important and crucial role is this battle against national liberation, progress and freedom.

Lest we forget:

Vietnam

From August to November 1945 Japanese soldiers in Vietnam were re-armed, by the British, to be used as a force against the Vietnamese Viet Minh, the national independence force led by Ho Chin Minh, in order to allow the French time to organise their forces to regain their colonialist control of the region. The Viet Minh had consistently fought against the Japanese invaders, the French had surrendered to the Nazis quite quickly and half the country was under a collaborationist government.

Indonesia

The British were involved in one battle during October and November 1945 against pro-independence Indonesian fighters in the battle for the city of Surabaya. British troops came with tanks, naval support – in the form of 2 cruisers and 3 destroyers – and air support from the RAF. The British ‘won’ but the battle became a clarion call for independence fighters in the future. Thousands of local people lost their lives.

Palestine

British forces had been in Palestine since the end of the First World War and became increasingly in conflict with the Palestinian population as more and more Jewish immigrants arrived in the country following the Balfour Declaration of 1917 – which promised ‘a national home for the Jewish people’. This decision didn’t take into account that there were already people living on the land and to make the declaration a reality some of these people would have to move. This led to increasingly violent conflicts between the British and the Palestinian Arabs before 1939 and once the war in Europe had been won and the Holocaust became widely known it was only a matter of time before the State of Israel would come into existence. A UN decision at the end of November 1947 came up with a ‘solution’ of the partition of Palestine. This wasn’t accepted by the Palestinians – it was their country and who were European powers to say otherwise – nor the Israeli settlers – who wanted it all.

Although the British were attacked by various Jewish terrorist groups (the leaders of which were later to hold high political office in the state of Israel) they stood aside as the date for the Declaration of the State of Israel (May 15th 1948) approached and the Jewish settlers carried out massacres such as the one of the village of Deir Yassin. This is a sore in that part of the world which has been festering ever since, with the suffering of the Palestinian people become greater day by day.

Greece

In March 1946 British forces continued its support of the Monarchist government in Greece. This had been ‘a government-in-exile’, i.e., the King ran away when the Fascists invaded. The Communist guerrillas who didn’t have that luxury stayed and fought against the invaders. Once the Nazis were thrown out at the end of 1944 the British were there to help reinstate the monarchy and gave support to a ‘White Terror’ against left-wing movements within the country. This ultimately led to the ‘Generals Coup’ of 1967 and then seven years of military, fascist rule.

Albania

In May 1946 a small convoy of the British Navy sailed through the narrow Corfu straights between the Greek island and Albania. This intimidation of a country with a tiny population who had liberated itself from the Nazi invaders in November 1944 was all part of the British plan, with the aid of its far superior armed forces, to undermine the Albanian Communist Government. As in Greece, Britain favoured the cowardly monarchy that had run away when the Italians had invaded in 1939, this time the self-proclaimed King Zog, and subsequently tried to infiltrate spies and saboteurs faithful to British interests, this all failed miserably.

China

In April 1949 the British Royal Navy ship, The Amethyst, was sent up the Yangtze River in China. This seems to have been more of an example of latter-day colonial arrogance on behalf of the British government and a similar attitude in the Admiralty. They seemed to be totally oblivious of the fact that tens of millions of Chinese men , women and children had died at the hands of the Japanese invaders; that the Communist Red Army under the leadership of Mao Tse-tung had played the major role in the defeat of that invading force of fascists; and that for four years they had been fighting, and were close to defeating, the capitalist favoured nationalist forces of the Kuomintang – who Britain subsequently recognised as ‘China’ (although limited to the island of Taiwan) in the United Nations until 1971. As in all these situations there’s a huge dose of hypocrisy. What would be the reaction of the British state if a Chinese warship were to start going up the Thames to ‘protect’ the Chinese Embassy, the excuse used in 1949?

Malaya

The British anti-guerrilla campaign in Malaya, starting in 1948, was euphemistically called ‘The Malayan Emergency’ – it’s interesting that after 6 years of war the use of the term was avoided so as to con the British populace that they hadn’t come out of one war to go into another. This was a dirty war fought in a manner that was to become the norm in Africa, Asia and Latin America for the next 50 years. Here the people were fighting for control of their own country opposed by a colonial power. As many of the guerrillas were of an ethnic Chinese background one of the tactics of the British was to use a ‘divide and conquer’ approach, pitting ethnic groups against each other.

The British troops in Malaya were also the first to use the tactics that the Americans were to perfect in Vietnam in the 1960s. Torture of captives was common, the tactic known as ‘search and destroy’ was widespread and the burning of villages was a matter of course, a shoot to kill policy was in place – meaning that if you were in the wrong place at the wrong time (even if where you lived) you could die, whole villages were ‘resettled’ (read imprisoned in controlled areas) so they could not aid the guerrillas, the use of defoliating chemicals was used to clear the jungle of shelter for the insurgents, and massacres of entire villages were part of the British tactics. One of those villages was a place called Batang Kali, the story of which is very similar to the case of My Lai in Vietnam in 1967, and like the later example of murder by imperialist troops not one British soldier was held to account.

Korea

The Korean War took place between June 1950 and July 1953, when an armistice was agreed but not a long-lasting solution. The division of the country was as a consequence of conferences between the Allies in the final months of the war and shows that matters were not always thought through by the Soviet Union – it seems they didn’t fully recognise the antagonism they would have to face from the capitalist nations, who were planning the ‘Cold War’ before the gunfire of WWII had ended. Using the Soviet Union’s boycott of the United Nations Security Council (in support of the People’s Republic of China’s rightful representation in the international body and hence unable to exercise the right of veto) with the US and the UK in the forefront of rhetoric and actual ‘boots on the ground’, an international force was sent in an anti-Communist crusade – a situation similar to which we can all recognise to date. A total of 87,000 British troops (including conscripts) were sent to Korea, resulting in a 1,000 fatalities. The country is divided to this day with occasional flare-ups, either militarily or in a war of words.

Kenya

As the British armed forces became involved in an increasing number of anti-colonial struggles on moving into the 1950s it’s possible to see how ‘tactics’ used in one place were repeated, and often refined, in others. The Mau Mau Uprising (again a loaded word that indicates the actions of the local populace was somehow illegitimate) was the name given to a liberation movement that fought the British from 1952 until 1956, when the struggle was all but lost by the Kikuyu fighters. In all these actions what are described as ‘war crimes’ can be attributed to the British forces, whether they be actual British soldiers or militias, auxiliaries recruited locally.

In Kenya concentration camps were established, often in very remote areas to keep the activities secret from the rest of the population. (Here it should be remembered that concentration camps were not the invention of the Hitlerite Nazis from the 1930s. No, the Nazis took their lead from the tactics used by the British at the end of the 19th century in their wars against the Boers in South Africa.) Torture was common and recent attempts by those who suffered at the hands of the British to get some sort of redress have been told, surprise, surprise, that the relevant documents have gone missing. There are a number of examples were captured insurgents were clubbed to death and a number of massacres of the local population are also documented.

Cyprus

A move by the British to move their Middle East Head Quarters from the Suez area of Egypt (presumably due to the hostility of the nationalist government of Nasser) to the island of Cyprus in 1955 was the spark to ignite both the Greek and Turkish populations desire to separate from the British and unite with their respective mainland countries. A total of 371 British soldiers died in the 4 year period but figures of Cypriot casualties are unclear – though they would have been much higher. Documents released in 2012 seem to show that, as in other places where the British fought to defend a dying colonialism, they were able to act with impunity in the way they dealt with the locals. To give an idea of the situation I’ll quote from an article in The Guardian newspaper just after the release of the documents: “A young British army officer recorded seeing 150 soldiers indiscriminately “kicking Cypriots as they lay on the ground and beating them in the head, face, and body with rifle butts”.”

Suez

In 1956, in response to the Egyptian President Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal the British, together with the Israelis and the French, concocted a scheme to invade the country. Although this was a short-lived occupation and really a debacle for the British and the French before they left there was a tally of 4 to 5 thousand dead Egyptians.

Oman

Oman in the 1950s was somewhere between slavery and feudalism. All power and resources where in the hands of the Sultan, who lived in a palace, which he rarely left, and was serviced by hundreds of slaves. There was no development, no schools, no health care and disease was endemic. As a result there was an inevitable rebellion. But, to paraphrase Franklin D Roosevelt when he was referring to the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza, ‘He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s Britain’s son of a bitch’. He was also anti-Arab nationalist, something the British liked after the disaster of the Suez Crisis, and he allowed the British to build a couple of air bases in a strategically important part of the world.

This was a ‘war’, which began in the middle of 1957, fought almost exclusively, at least initially, by the Royal Air Force. In supporting the Sultan they followed the tactic of making it so dangerous and unpleasant for anyone to support any opposition to the staus quo that they would think twice to do so. They also attacked water supplies, crucial for survival in such a desert country. These were war crimes in anyone’s definition but the pilots seem to, literally, get away with murder as they are so far from the actual killing zone – just like drone pilots today. If force needed to be used on the ground the British were happy to provide the weapons. Once the RAF had bombed the rebel strongholds to dust the SAS were sent in to finish the job, in the process gaining a reputation for being the hard men of the British Army but really just carrying out mopping up operations. By July 1959, the Sultan, with the military might of the British behind him, seemed to have won.

Brunei

An anti-colonial rebellion broke out in December 1962. Intelligence of the intention of an insurrection got to the British about a month before it was due to begin, thus allowing themselves time to organise a response. It seems that overwhelming force, with infantry regiments, including a couple of Gurkha regiments, on the ground as well as Royal Navy and RAF support was able to stop the rebellion before it gained any momentum.

Indonesia

Although British troops weren’t directly involved in the October 1965 military coup which put the pro-Western Suharto in control of the country and led to the murder, over the next couple of years, of millions of Communist and trade unionists, the Royal Navy did play the role of protectors of a boat load of Indonesian soldiers on one of their killing sprees. This shouldn’t be a surprise. The Labour Government of Harold Wilson knew what was going to happen before the event, virtually giving Suharto the green light. Communist led attempts at insurrection in Sarawak and the anti-colonial (British) failed insurrection in Brunei had both been supported by Sukarno and his removal suited Britain’s political and economic interests in the region. As was, and still is, the case the question of oil came high on the agenda.

Aden

Aden, which is now part of Yemen, had been under the control of the British since 1839 but at the end of 1963 (I know that’s a long time before getting fed up with foreign domination) the local people had had enough of colonial rule. The British response to this was to declare another ’emergency’ and send in the Army’s 24th Infantry Brigade and nine squadrons, helicopters as well as aircraft, of the RAF. This was a short but very intense conflict, with the balance of power changing after each battle. The commander of the 1st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders was nicknamed ‘Mad Mitch’ so that will give you an idea of how the battle was fought on the British side. The British left, earlier than originally planned, in November 1967. Around 60 British soldiers lost their lives but the number of local fighters who were killed is unknown.

(As we were nominally supposed to be in ‘Peace Time’, it’s interesting to note that 1968 was the first year since the end of the Second World War when British troops were not in a combat role somewhere in the world. I think it’s true to say the only year from 1945 till now.)

Ireland

British troops were sent into Ireland, in the most recent version of ‘The Troubles’, on 14th August 1969. Although it could be true to say, initially, they were welcomed by the Catholic community that soon melted away. With Ireland it’s difficult to know where to start. It would depend where you stand on Ireland whether this was a national, civil conflict or the perpetuation of colonial rule. Whatever interpretation you choose it brings up difficult questions. If you think that Northern Ireland is part of the UK then British troops were mistreating, torturing and generally terrorising British citizens. If you believe in an All Ireland Republic this was a matter of the colonial conflict getting closer to home.

British troops in Ireland: kicked in people’s doors in the middle of the night; soon had their backs to the Unionist attackers and faced the Republicans trying to defend themselves; killed children by firing ‘battery enhanced’ rubber bullets into their faces; killed civilians in a virtual ‘shoot to kill’ policy; the ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacre in Derry – in recent days a soldier has been arrested for this, but, as always happens in these circumstances, a lowly soldier becomes the scapegoat for overall Army policy; the Springfield Massacre in Belfast where British snipers shot 5 people, including a 13-year-old girl and a priest; the Ballymurphy Massacre when eleven civilians were killed; introduced Internment; and generally made life miserable for the people of Northern Ireland and despite the Good Friday Agreement the underlying issues remain.

(When it comes to Army recruitment the worsening situation in Ireland changed the way the Armed Forces presented themselves. Into the early years of the 70s the call was for young people to ‘Join The Professionals’. When that was seen as joining a bunch of thugs who kicked in people’s doors in the middle of the night advertising for the army virtually disappeared from the scene.

Ireland has now been all but forgotten in the public consciousness – in the mainland if not on the island itself. Despite the disastrous wars that the UK has been involved in since 2002 there is a new level of confidence in the state. However many soldiers might die or return with psychological issues there seems to be no shortage of volunteers to join up. Whether the advertising campaigns are really necessary is another matter, it does shovel money into the pockets of companies who support the State but more importantly keeps the idea of an internationally capable armed force in the public thinking.)

Muscat and Oman

The issues that caused the people to rise up against the Sultan in the 1950s didn’t go away, although the revolutionary forces were severely weakened by British military action. By 1970 oil was a much bigger player in the country and the rebellions continued to break out. Instead of making efforts to ameliorate the condition of the people the British government (Labour) instituted a coup against the old Sultan (who was past his sell by date), brought the more compliant son to the throne, and then used the RAF to again bomb the poor peasants out of existence.

Malvinas

The war with Argentina over the Malvinas was a nasty, tacky war encompassing all those reactionary and archaic aspects of wars fought when Britain was dominant in the world and ‘the sun never set on the British Empire’ and the short campaign brought out the worst in the British population. Those aspects of racism and jingoism latent in the country were given free rein by the Thatcher government, who revelled in the opportunity to distract people’s attention away from their inability to deal with the economy. ‘Victory’ in the South Atlantic also allowed those war-mongers within society to attain a level of influence that was still palpable more than twenty years later when the never-ending ‘war on terror’ was declared. More than a thousand men were to die in that short war, a quarter of them British.

Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and ……

Perhaps it’s unjust to lump all these countries together but circumstances in the last 13 years make it difficult to separate what happens in one country from the effects on another. There is no perceivable end to this war, even politicians saying (in a perverse way to gain support for their policies) that this was is a generational war, one that will go on for years. ‘Victory’ in one place only means the fighting break outs in another. So far 465 military personnel have died in Afghanistan, 179 in Iraq. When it comes to wounded the situation is not so clear, in Iraq almost 6,000 but the figures for Afghanistan are obscured, presumably to keep as many people as possible in the dark about the true human cost.

But the figures become another matter when we consider casualties amongst those opposing the invasion of their country and civilians who get caught up in the fighting. Those figures are probably well over 200,000 but we’ll probably never know the exact figures as numbers are a political game. And from experience of the past the numbers of enemy combatants will always be exaggerated, and those of civilians played down, to demonstrate that the ‘good guys’, i.e., us, are winning.

Industrial Disputes in Britain

Another matter which is never considered is the role that the Armed Forces have played in industrial disputes in this country. Up to the mid-1980s, when trade union activity dropped considerably with the success of the Thatcher government’s anti-union policies, especially with the defeat of the miners in 1984/5, the British Armed Forces were called out almost 50 times to basically scab (strike break) on behalf of the employers. This was at a time when trade union membership was close to 12 million, so hardly a minority group within society – although lack of solidarity amongst trade unionists often meant that groups could be picked off one by one – the tactic learnt long ago by capitalism but still not by those who oppose the rotten system.

When it comes to party politics in Britain it should be pointed out that the colour of the government at any time in the last 70 years has played no part whatsoever in whether British Armed Forces were sent to other parts of the world or not. The Labour Party has been as willing to send troops to maintain British imperialism’s control of various countries, considered by capitalism to be of such importance that force was necessary, as the ‘traditional’ representative of the ruling class, the Conservative Party. Even in opposition these parties play a game and might make noises around the execution of the deployment but never, ever challenging the morality of the issue.

My reasons for this long list (longer than even I remembered) of occasions where British Armed Forces have been in action since 1945 is to argue that it is impossible – if you have any moral compass whatsoever – to consider those who have been killed or wounded as having done so in order to make the world a better place to live, the sort of statements that have been bandied around in the last week or so leading up to November 11th – a phrase which I can’t remember being used in such the same way in previous years.

It seems that the longer the ‘war against terror’ goes on the more the British population in general are prepared to accept the cost that will have to be paid in men, women and materials – those at the receiving end of this mayhem not really being considered at all. There are crocodile tears for the refugees but the bombs continue to drop, drones get used more and more (becoming more terrifying to the people of the ground with the use of the ‘double tap’ tactic – where the drone will stay for hours if need be just to ready to send another missile on anyone who tries to help the injured.

One of the stated aims of even an imperialist army is to defend the people from the country which they originate but do the people of Britain actually feel any safer as a consequence of all these wars against diverse people’s throughout the world?

If wars against poor peasants in the past didn’t affect the civilian population of Britain that is starting to change. In my travels throughout the world I was always amazed that it was very rare to come across hostility from local people who had suffered under the British Armed Forces over the decades. That has changed now. The combined efforts of Bush and Blair have created a genie which will be very difficult (if not impossible) to push back into the bottle.

So have British troops, in the last 100 years, made ‘the world a better place’? I would suggest not. A better pace for the rich and powerful but not for ordinary working people, in whatever country and at whatever level of economic development.

Why do young men and women still volunteer to join such an organisation when it has such a history? I don’t know. There will always be the psychopaths who, if they did what they do in the armed forces in civilian life they would be pariahs of society. Put them in a uniform and they become ‘heroes’. But they, I would like to think, are in the minority – although I find it disturbing when a parent of a dead serviceman/woman will say that their son/daughter died ‘doing something they loved’, when the job of a member of an infantry regiment is to kill people’.

Way back in the 70s and 80s it was suggested that those who join (especially the Army) do so because they come from poor working class backgrounds and there’s nothing else for them to do. Even if that argument is correct the poverty of their origin does not give them license to go to other parts of the world and terrorise the local population.

And where does anyone think the foot soldiers to defend capitalism are to come from anyway? The highest casualty rate in the First World War was among the lowest ranks of the officer corp. Either because they were in the first ranks of those going ‘over the top’ or because they were shot so that the rest of the soldiers didn’t have to go ‘over the top’ at least they were fighting for a society that had benefited them.

Even in the 21st century troops after coming back from the wars in the east are complaining about the lack of support in civilian life. Don’t they have any idea of history? In the 1914-19 war they were promised ‘homes fit for heroes’, they didn’t get them. Why should the State act any differently now, especially when we are in a time of austerity where we are ‘all in this together’ and everyone must play their part?

I don’t want this country to keep sending its young people to fight wars for whom the ruling class are the only beneficiaries. I don’t want that we have to keep adding different campaigns to the list on the First World War memorials. But unless the people of this country stand up against these wars that is what will continue to happen, and now in a climate where people are so full of hate (and why is that surprising?) that they are prepared to bring the war back to the country which had sent the bombs to kill families on the other side of the world. These are very dangerous chickens that are coming home to roost.

For a time leading up to and in the immediate aftermath of the war against Iraq many people wore badges with the slogan ‘Not in my name’. That should be the slogan all the time, a slogan which shouldn’t be forgotten once the fighting has started and the bodies of those young people start to arrive back home. If the country is not prepared to see the processions through ‘Royal’ Wootton Bassett (something which the General Staff of the Army hated and which will never be repeated however height the casualties) then it shouldn’t allow those young people to be sent out in the first place.

That would be in a world without war – but there are far too many vested interests to allow such a situation to arise without a fight. To attain that would be definitely worth fighting for – a war to end all wars.