VI Lenin in Moscow

Here is a selection of the statues, busts and bas reliefs of VI Lenin to be found in Moscow. All of the below are accessible to the public (although on one or two occasions a little bit of imagination might be required to get close). There are more. Of those some are in locations which are difficult to enter, e.g. military or other government buildings or property.

To the best of out knowledge all the location details are correct. Apologies for any errors. If there are errors please let us know so they can be corrected.

You will see there is scarce information about all of those listed. If anyone can fill in the gaps or direct us to a source which will allow that to happen it would be appreciated.

It is hoped that, at some time in the future, this list will be augmented. There are supposed to be close to 100 examples in the Moscow area but many are under threat if the locations where they are found undergo demolition or development.

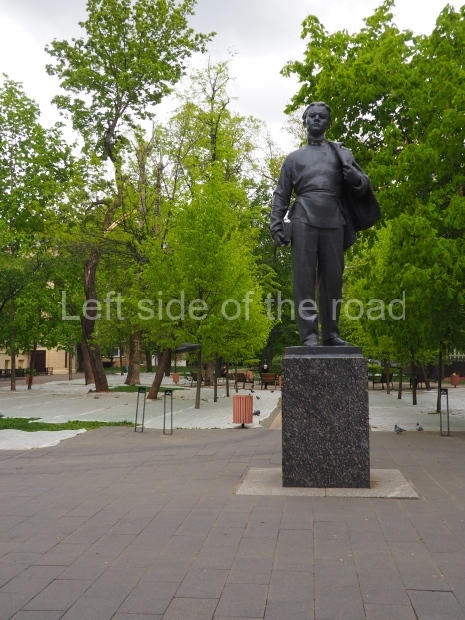

VI Ulyanov (Lenin) – as a student

Location; Ogarodnaya Sloboda Lane

GPS; 55.76535 N 37.64162 E

Sculptors; V.E. Tsigal, P.I. Skokan

Year; 1970

Notes; In July 2008, the monument was overturned by a strong gust of wind and broke into several pieces. In 2009 the monument was restored and installed in its original place.

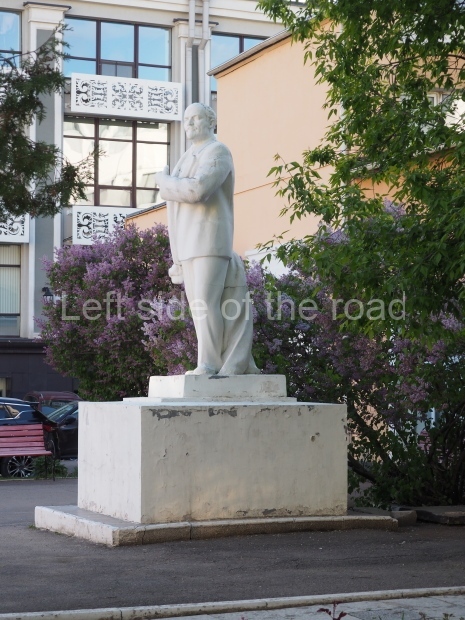

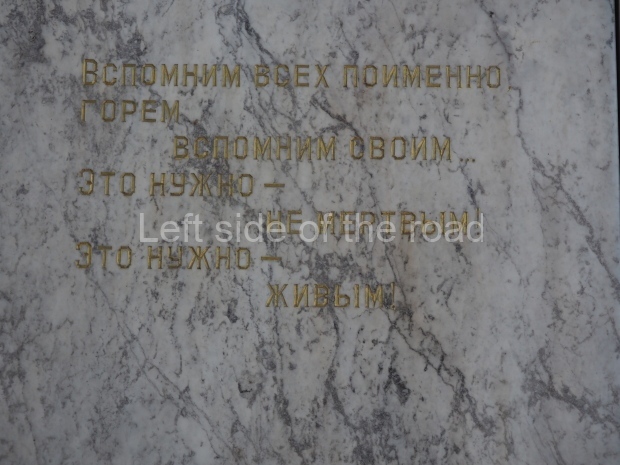

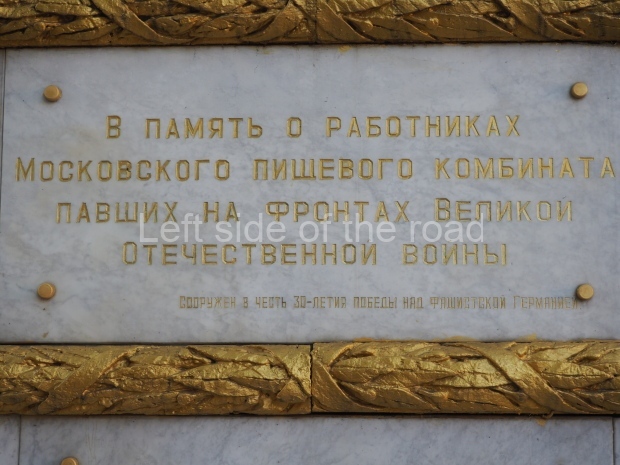

VI Lenin next to war memorial

Location; Perevedenovskaya Lane 13c6

GPS; 55.78009 N 37.64162 E

Sculptor/s; Sergey Dmitriyevich Merkurov

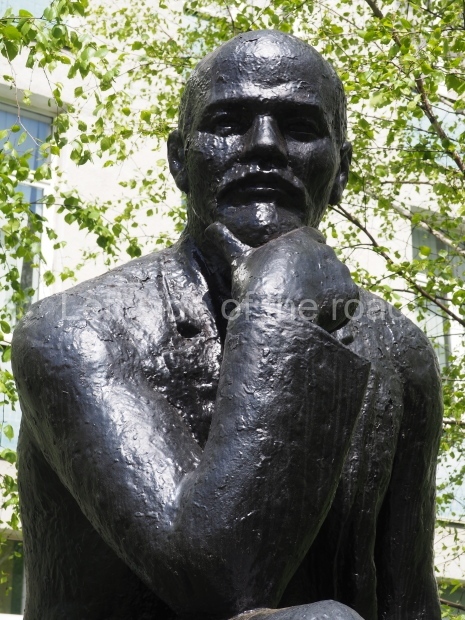

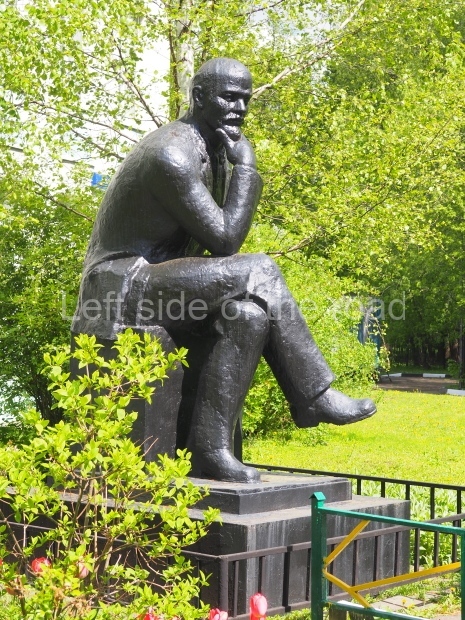

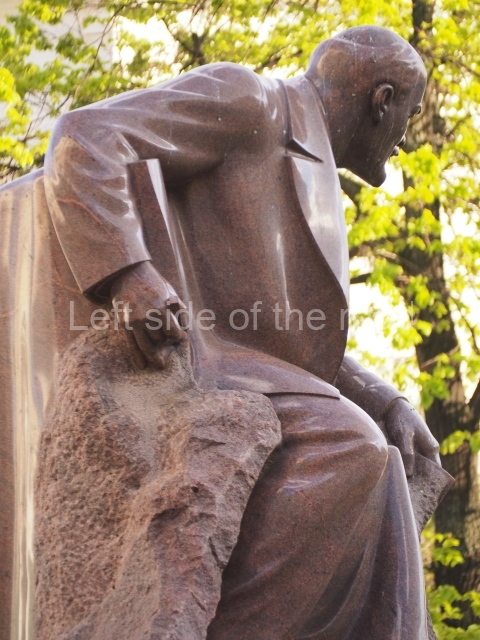

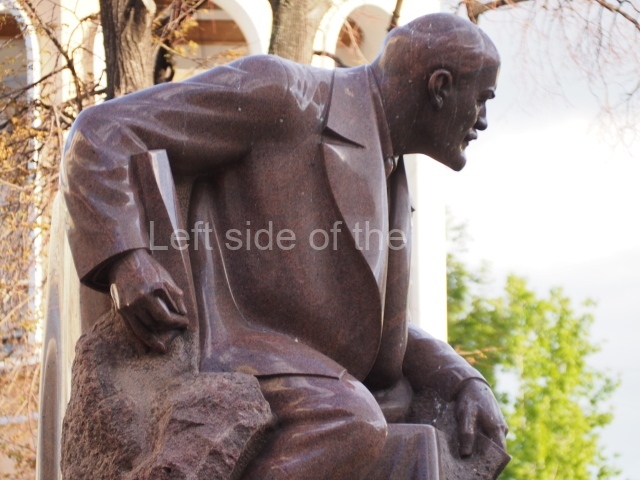

VI Lenin near Rimskaya and Ploschad Ilyich Metro stations

Location; Rogozhskaya Zastava Square

GPS; 55.74731 N 37.68190 E

Sculptor; G.A.Iokubonis

Architects; V.A.Chekanauskas, B. Belozersky

Year; 1967

VI Lenin being carried shoulder high by workers

Location; 1st Karacharovskaya Street 8c3

GPS; 55.73610 N 37,75598 E

VI Lenin in the garden at workers’ apartments

Location; Aviamotornaya Street 28/4

GPS; 55.74570 N 37.71874 E

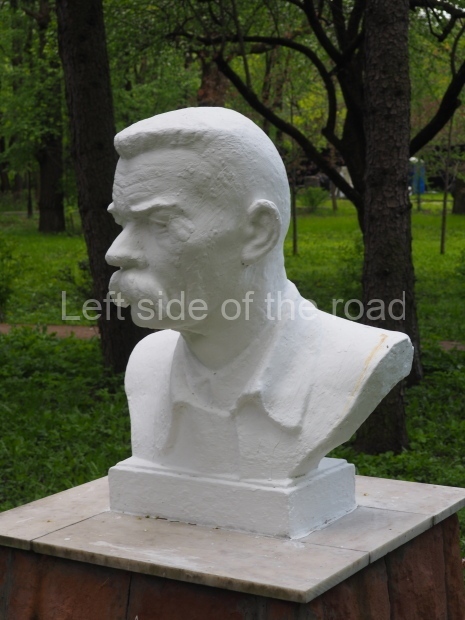

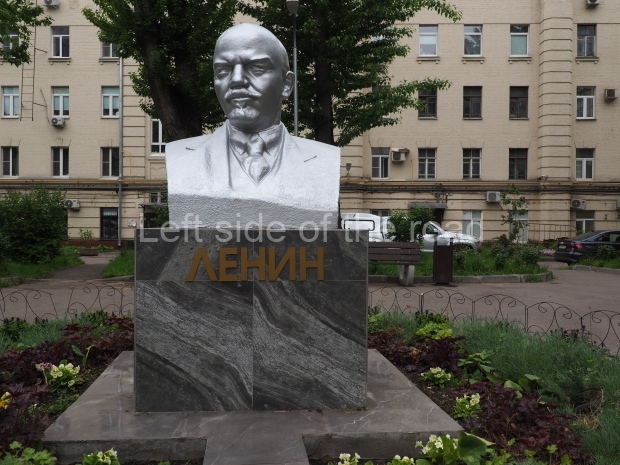

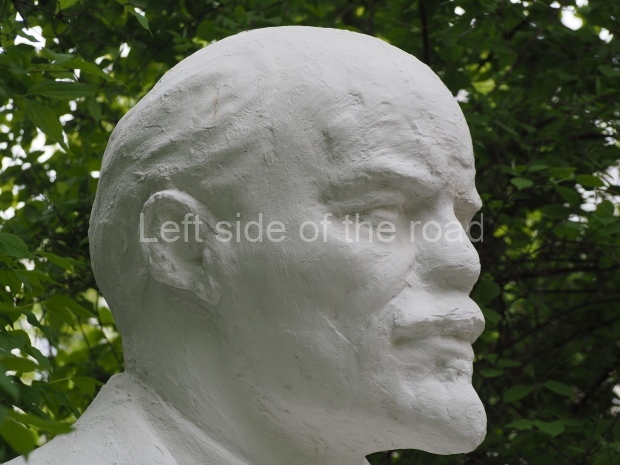

A bust of VI Lenin in a small pedestrian square

Location; Alexandra Lukyanova Street 7

GPS; 55.76828 N 37.66438

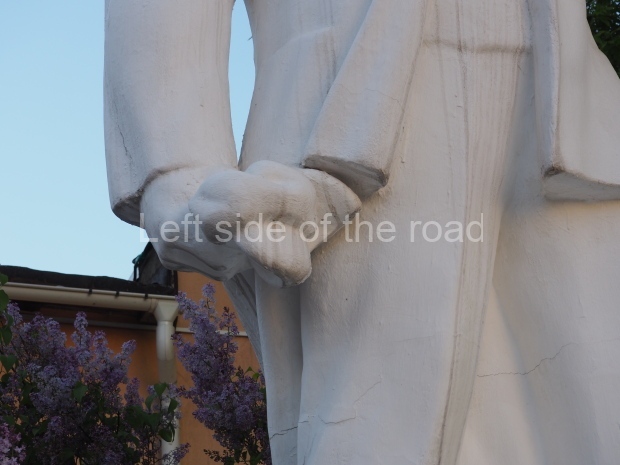

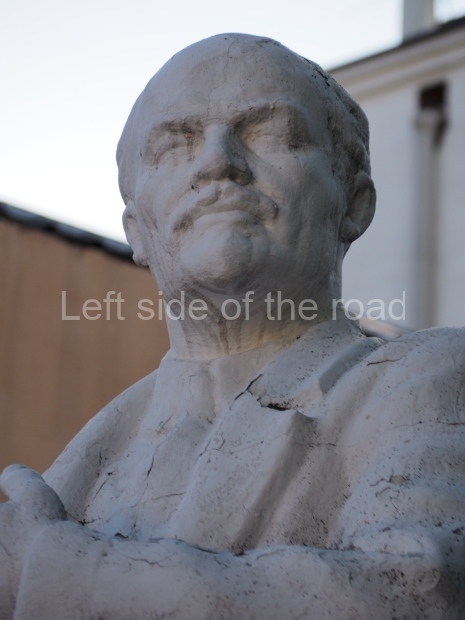

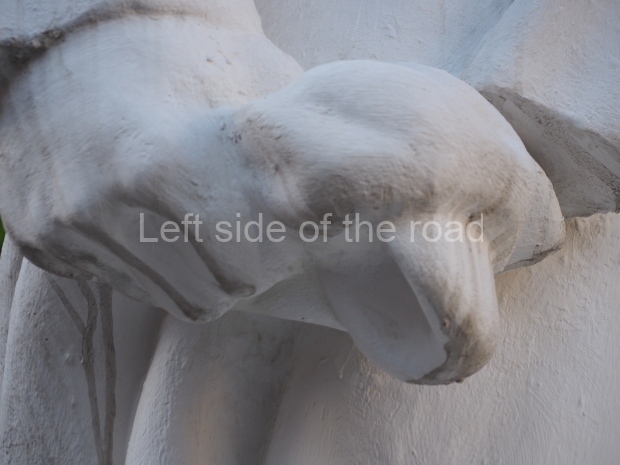

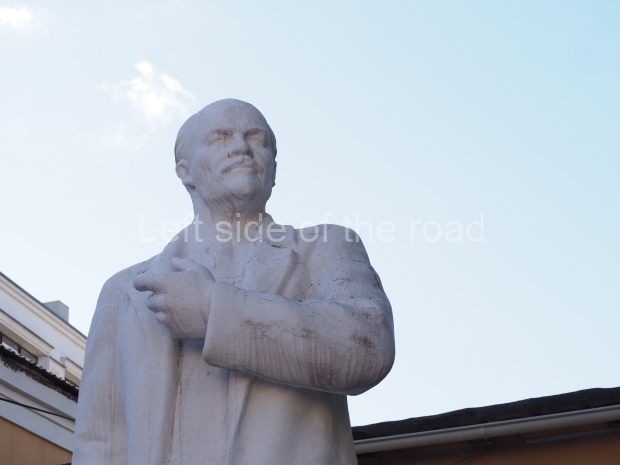

VI Lenin in a residential street

Location; Burakova Street 8c10

GPS; 55.76178 N 37.73039 E

VI Lenin at school

Location; Perovskaya St 44a, School Building No 796

GPS; 55.75311 N 37.78205 E

Sculptors; I.I. Kozlovsky, A.R.Markin

Year; 1983

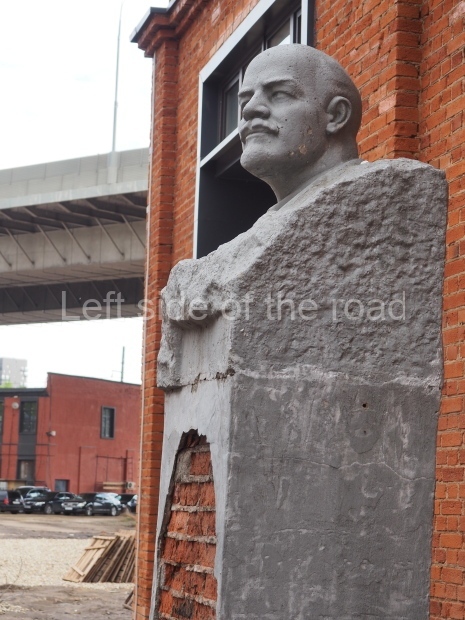

VI Lenin in a building site (at the time of the visit)

Location; Rabochaya Street 84c7

GPS; 55.73919 N 37.69611 E

Notes; The factory is in the process of being turned in offices/apartments. VI Lenin has survived (just) so far but whether his luck will continue to run is uncertain.

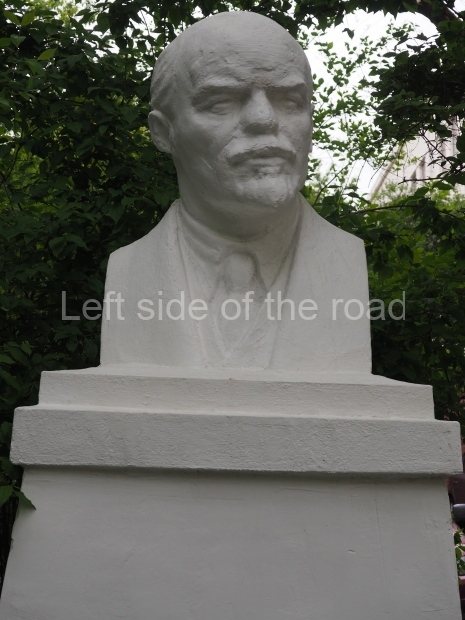

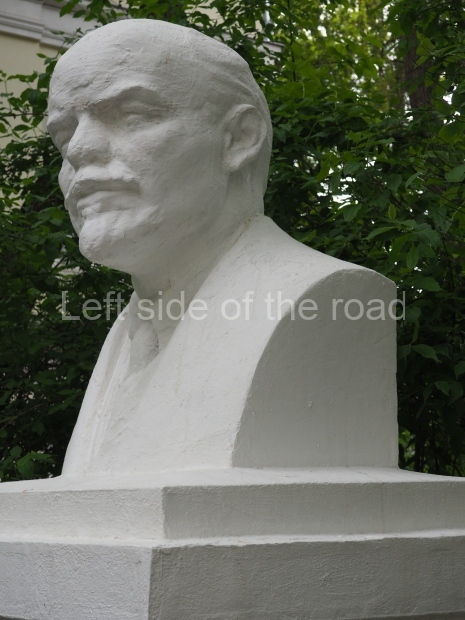

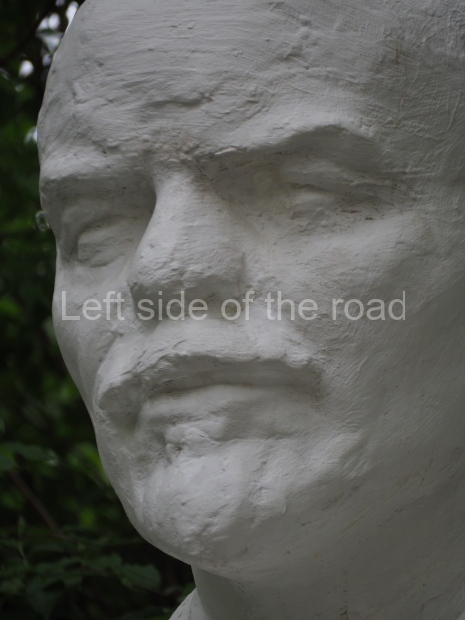

A bust of VI Lenin in the garden of a residential home for veterans

Location; Entuziastov Highway 88, Yablochkina House of Veterans

GPS; 55.76544 N 37.79635

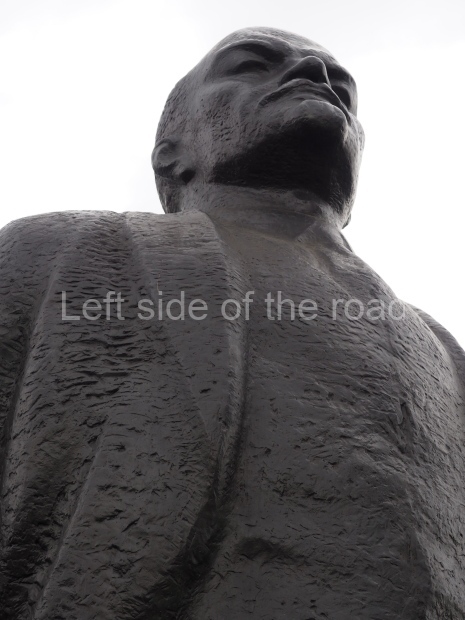

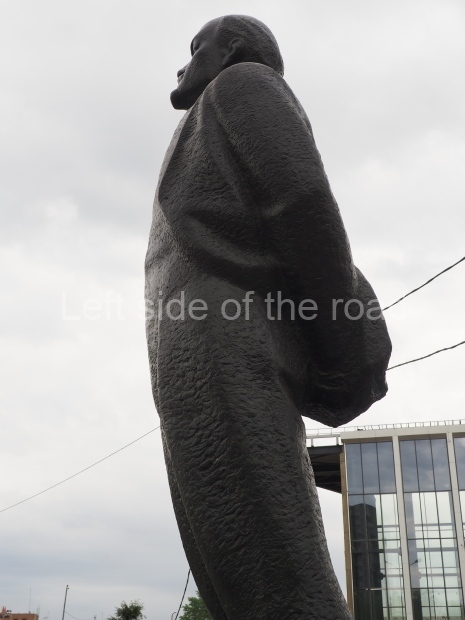

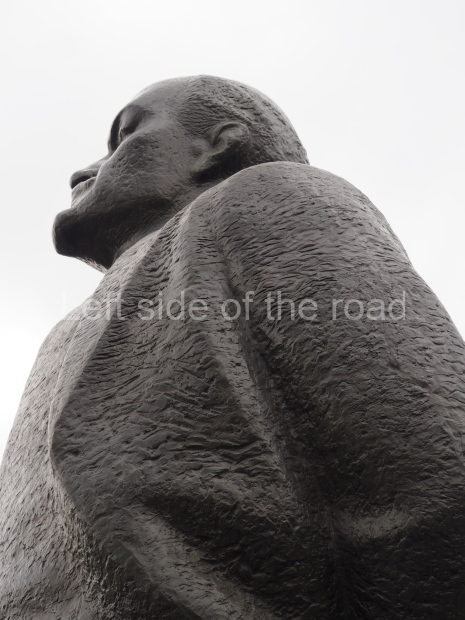

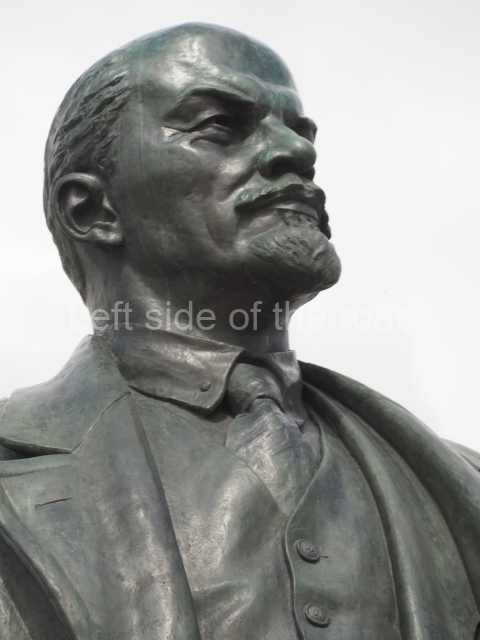

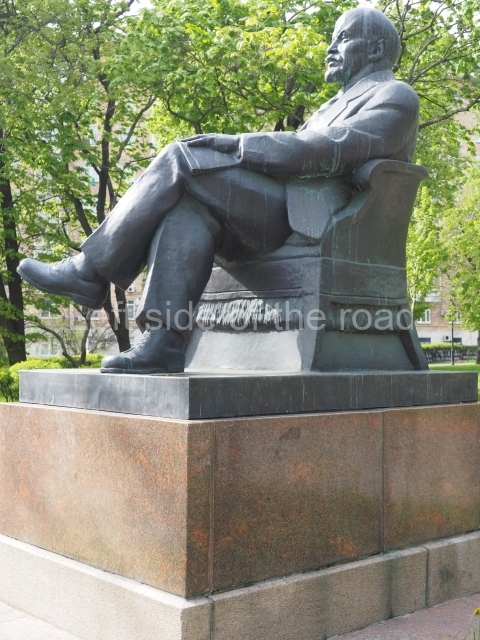

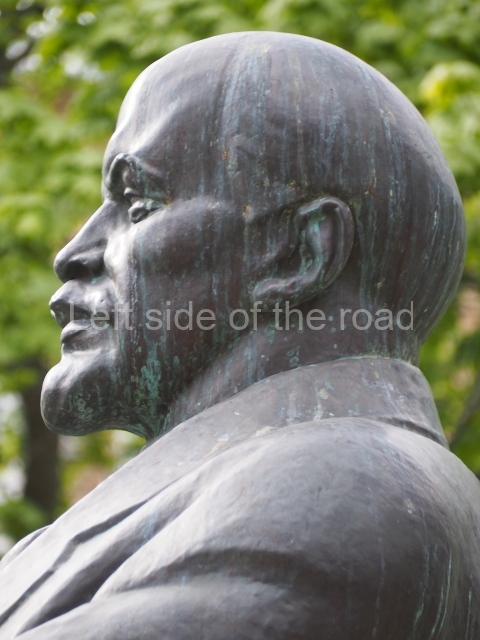

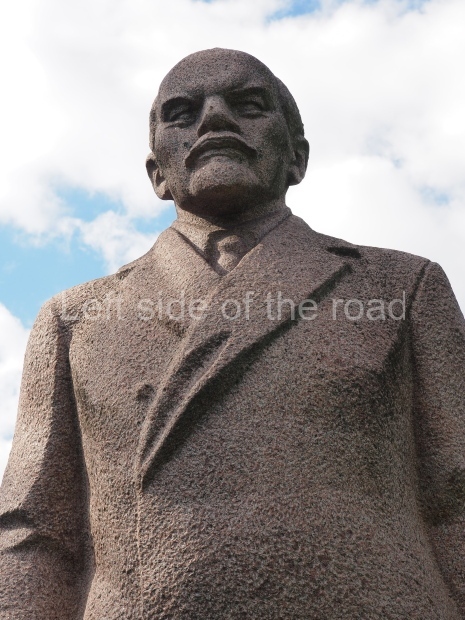

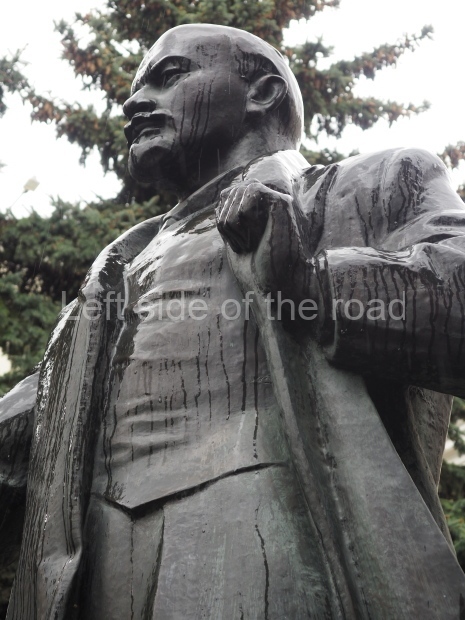

Statue of VI Lenin at the VDNKh

Location; In front of the main pavilion at the VDNKh park

GPS; 55.83109 N 37.62981 E

Sculptor; P.P.Yatsyno

Year; 1954

Blog post; Statue of VI Lenin at the VDNKh

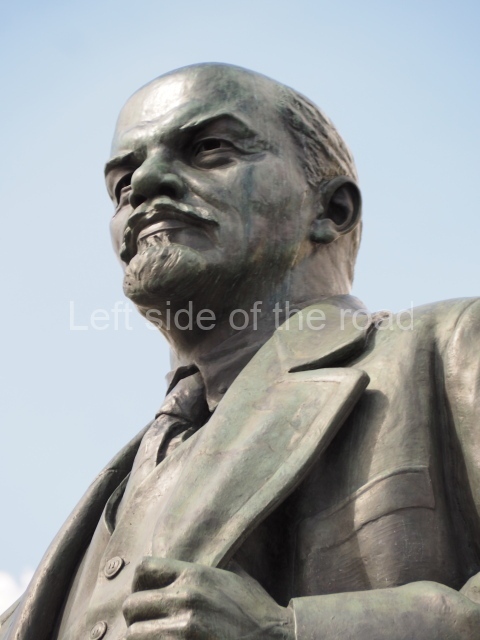

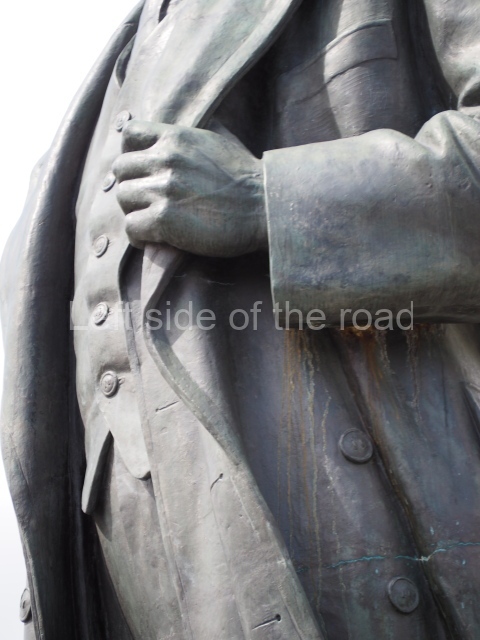

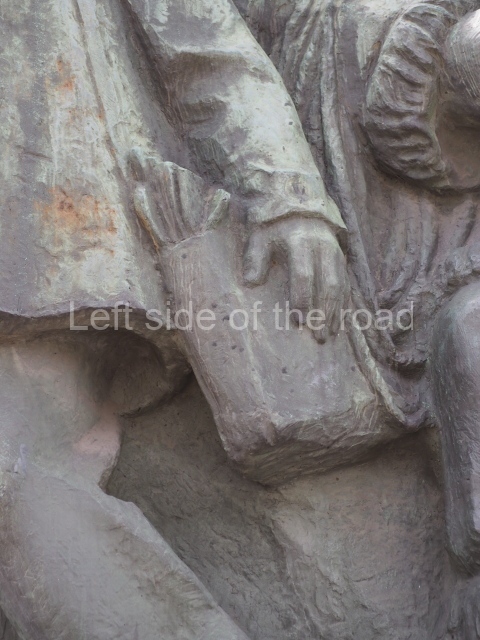

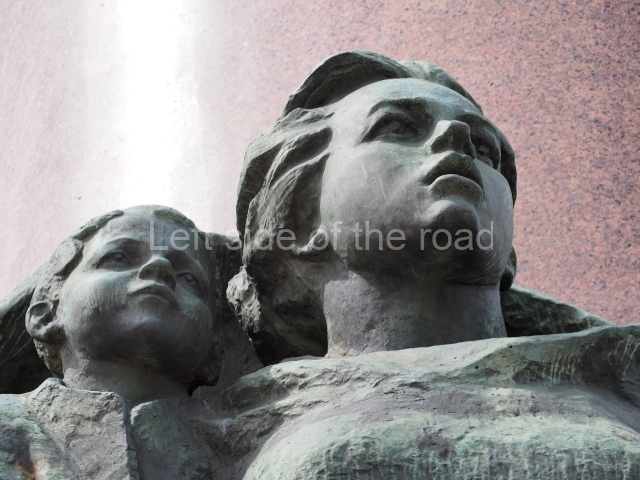

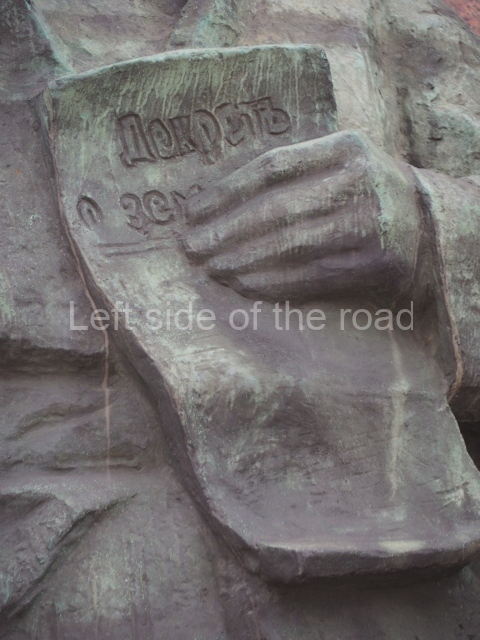

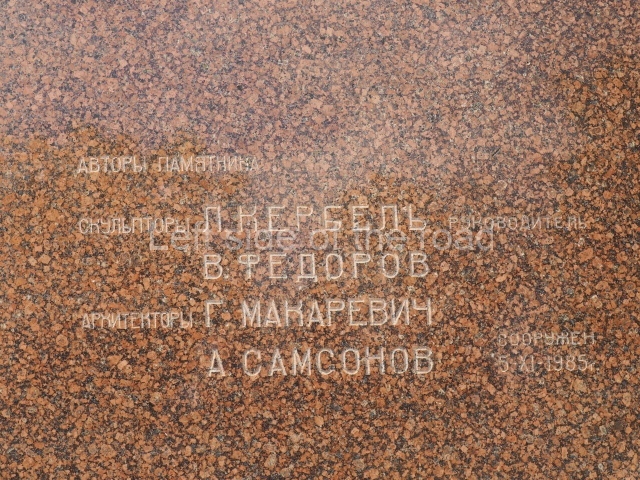

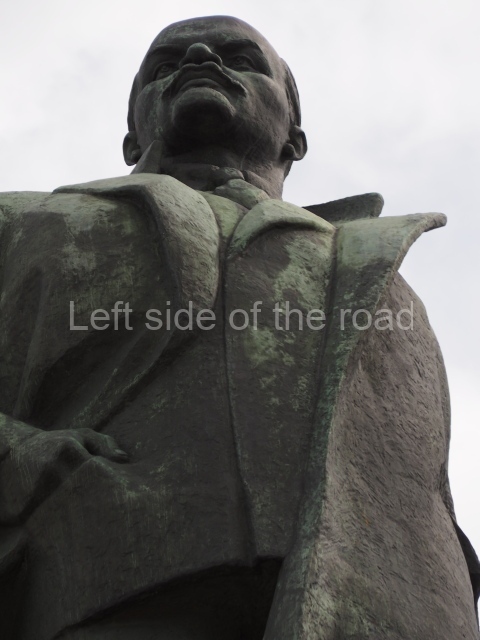

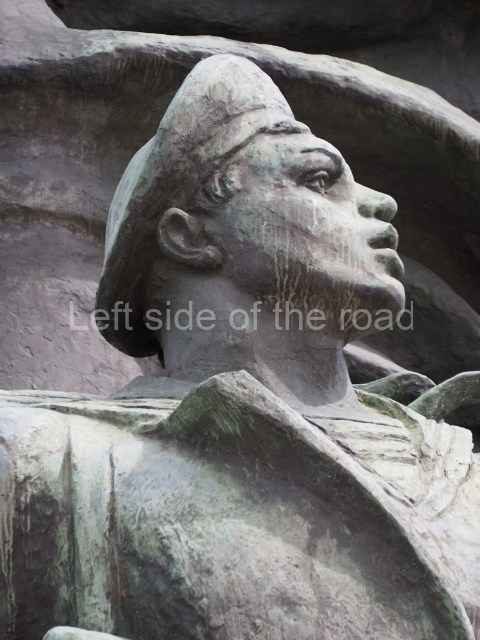

Lenin and October Revolution Monument in the Kaluga Square

Location; In Kaluga Square (formerly October Square), at the junction of Lenin Prospekt and Krymsky Val, opposite the main entrance to Oktyabrskaya Metro station

GPS; 55.729466°N 37.613176°E

Sculptors; . E. Kerbel, V. A. Fedorov

Architects; G. V. Makarevich, B. A. Samsonov.

Year; 1985

Blog post; Lenin and October Revolution Monument in the Kaluga Square

Monument to VI Lenin on Tverskaya Square

Location; Tverskaya square

GPS; 55.76233°N 37.61146°E

Sculptor; Sergey Dmitriyevich Merkurov

Architect; I.A. Frantsuz

Year; 1938

Blog post; Monument to VI Lenin on Tverskaya Square

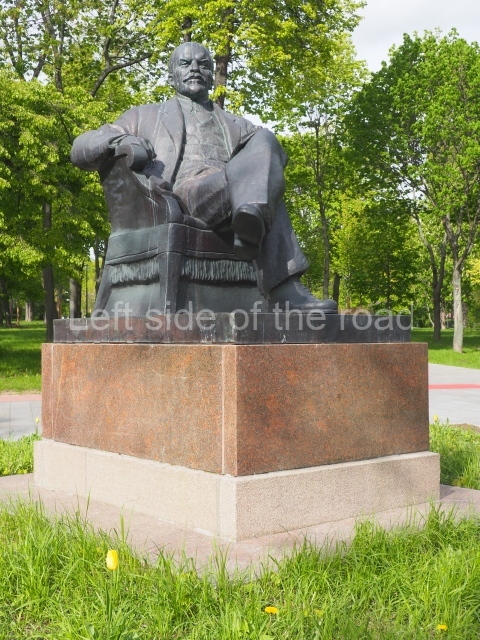

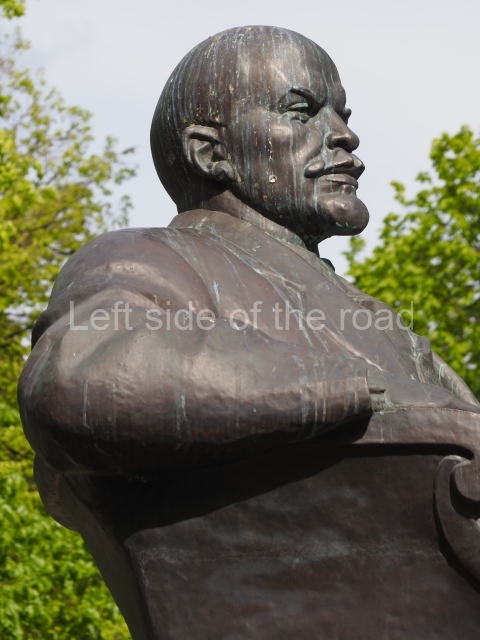

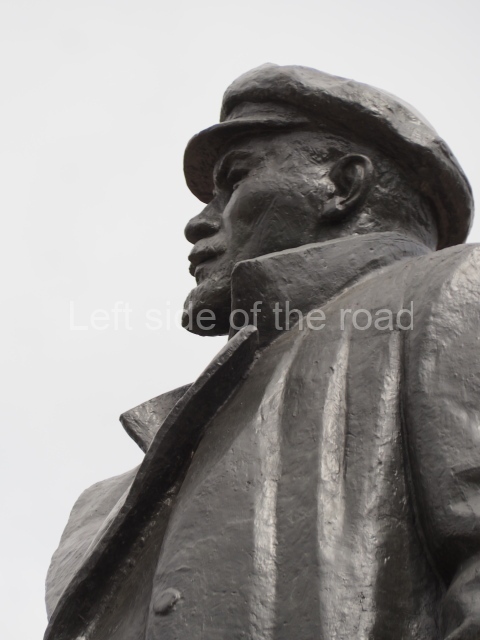

VI Lenin statue – Dekabrskaya Vosstanya Park

Location; At the far end of Dekabrskaya Vosstanya Park from the Ulitsa 1905 Goda Metro station.

GPS; 55.759523º N 37.558902º E

Sculptors; B.I. Dyuzhev, Yu.I. Goltsev

Year; 1963

Blog post; VI Lenin statue – Dekabrskaya Vosstanya Park

VI Lenin statue and assassination attempt memorial stone

Location; In a small park at the junction of Ulitsa Pavlovskaya and Ulitsa Pavla Andreyeva.

GPS; 55.72087º N 37.62862º E

Sculptors; V.B.Topuridze, K.T.Topuridze

Year; 1967

Blog post; VI Lenin statue and assassination attempt memorial stone

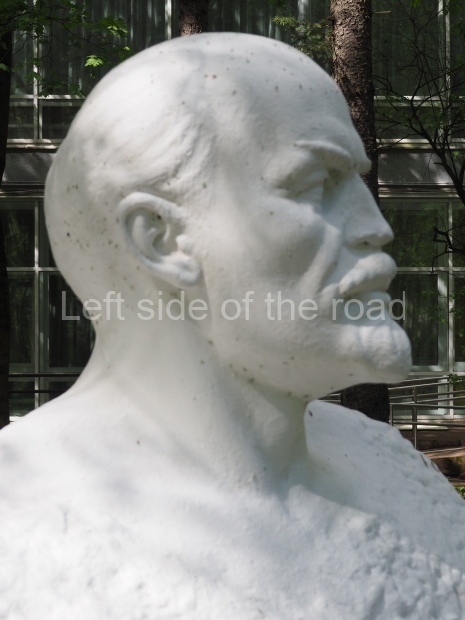

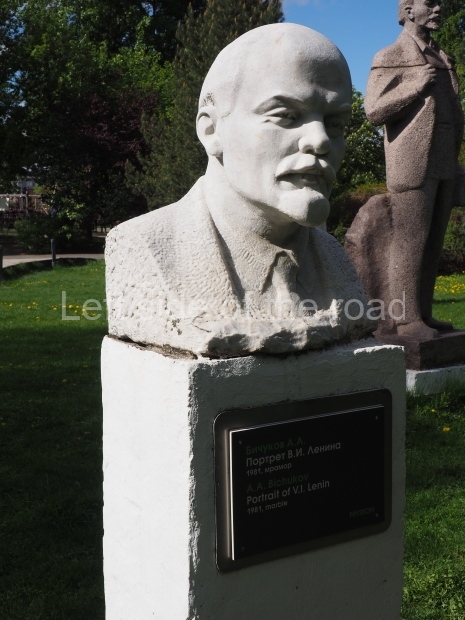

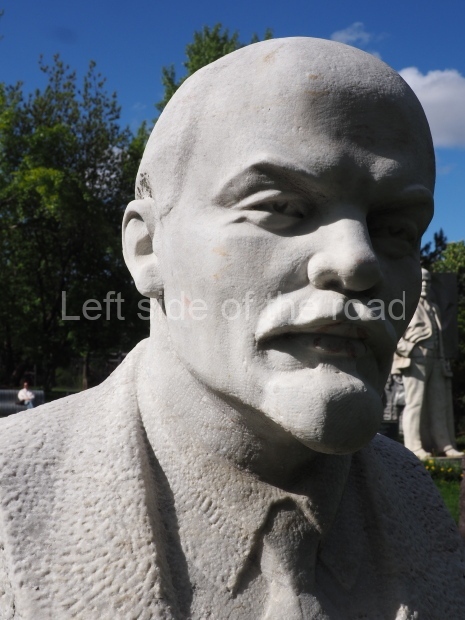

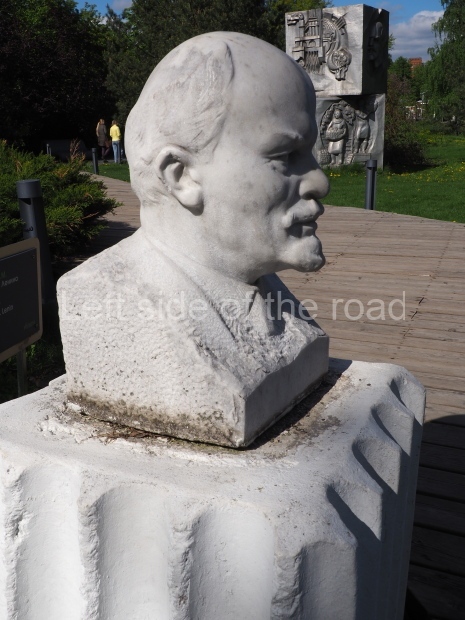

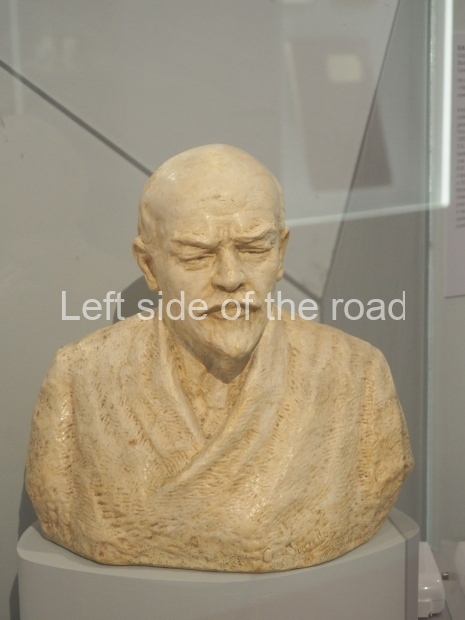

Marble bust of VI Lenin

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73416 N 37.60677 E

Sculptor; A.A. Bichukov

Year; 1951

Blog post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

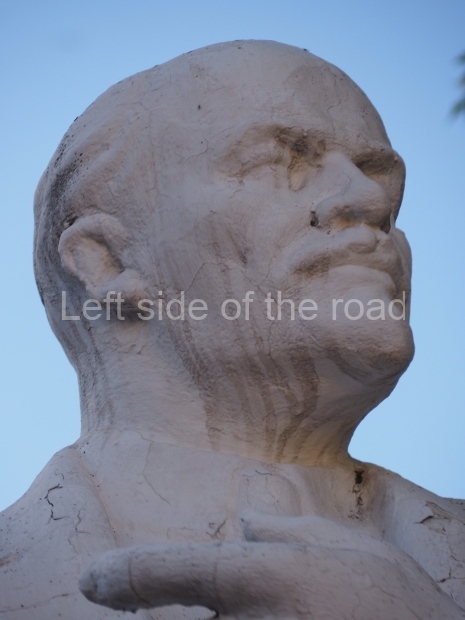

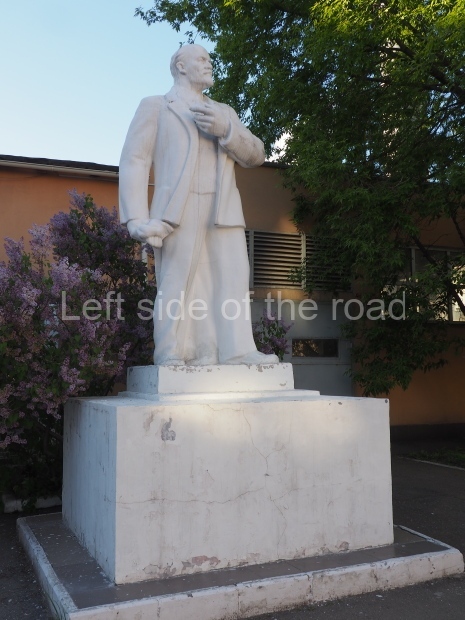

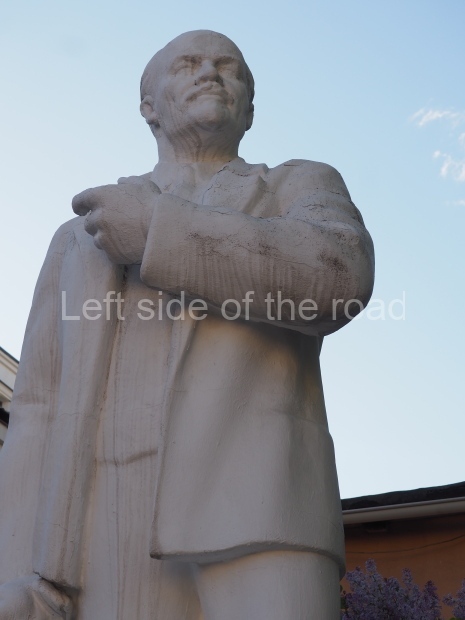

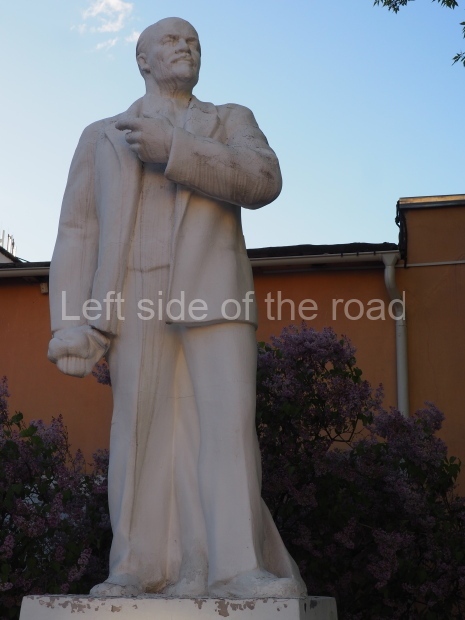

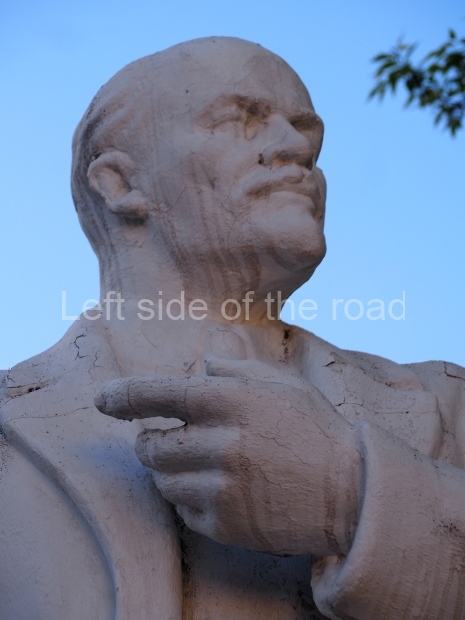

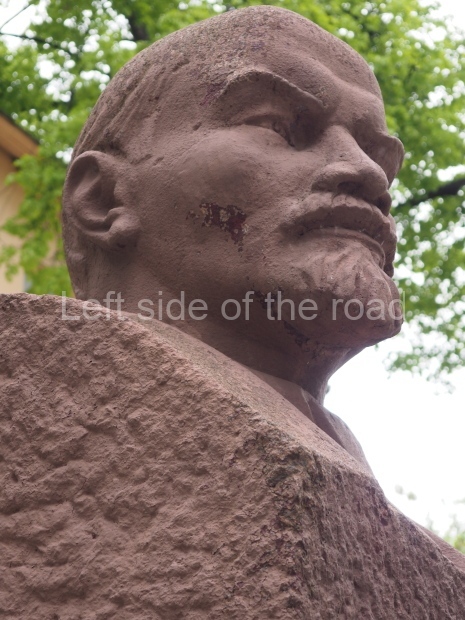

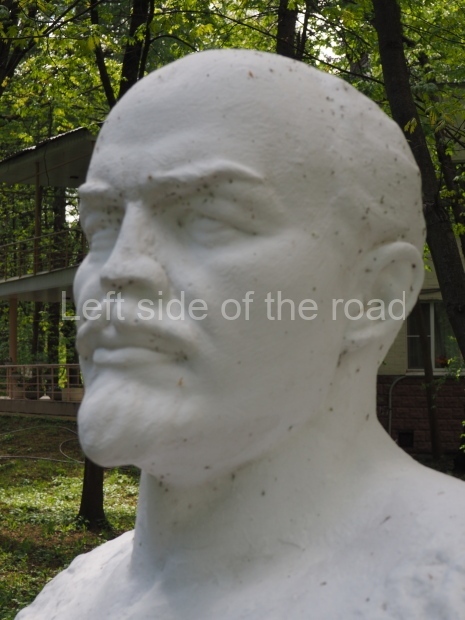

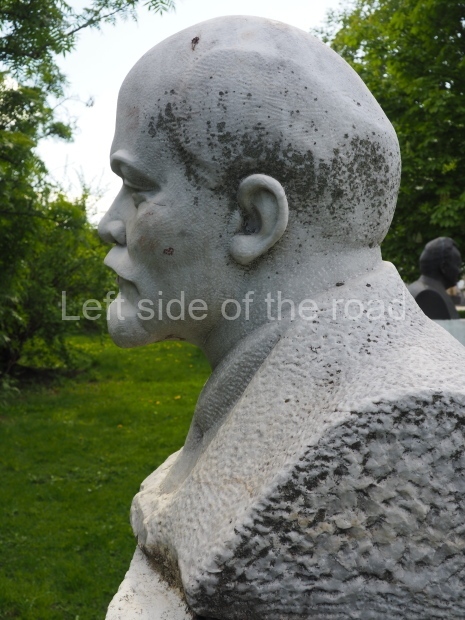

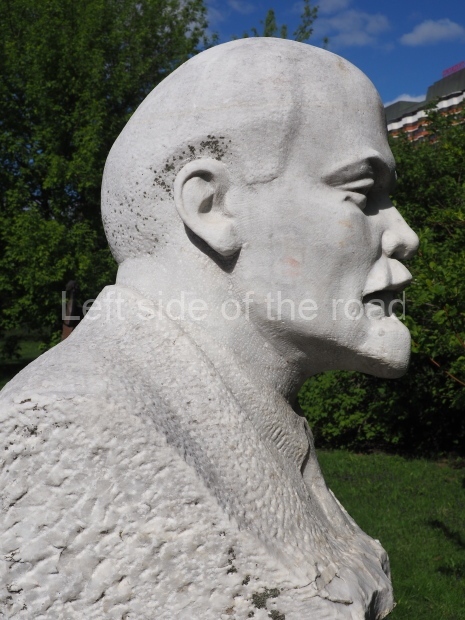

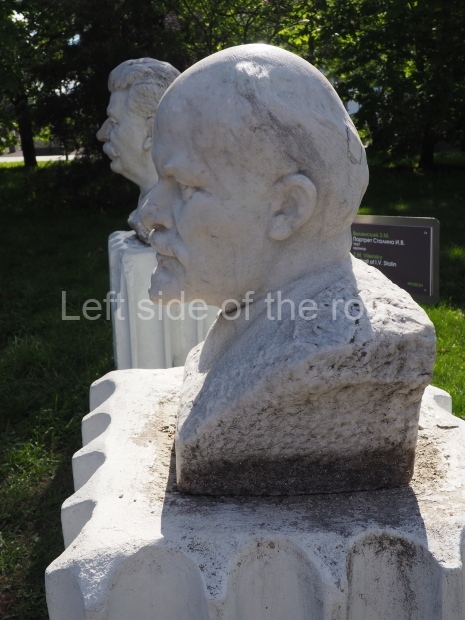

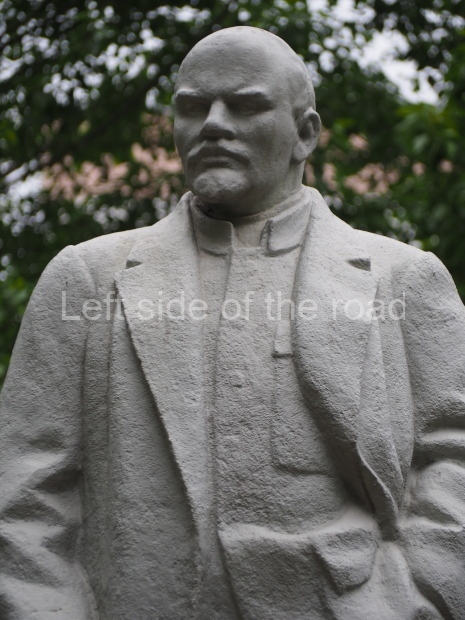

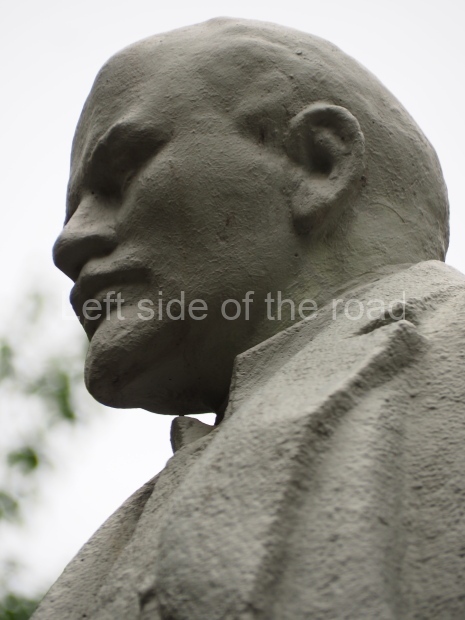

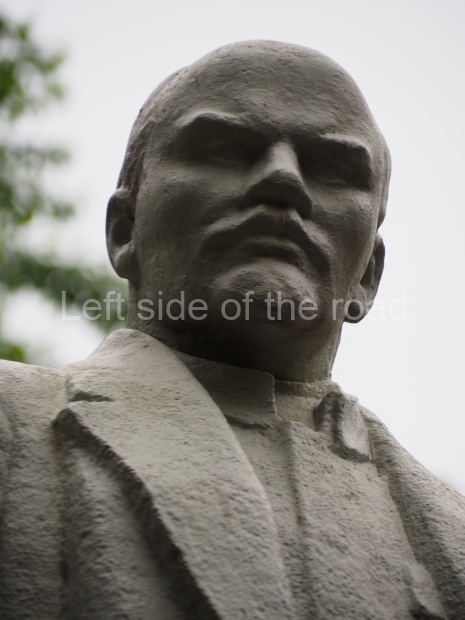

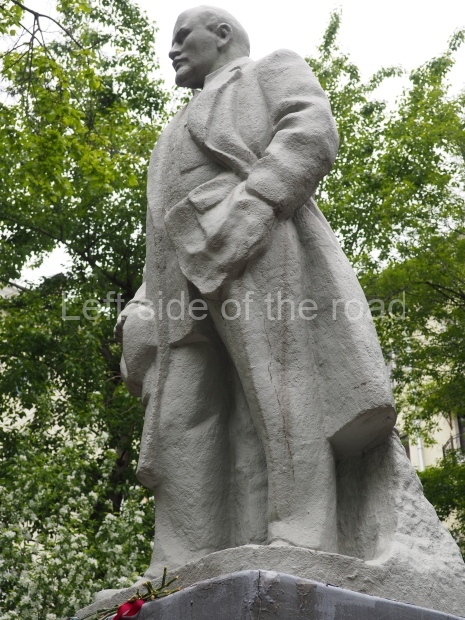

Standing, sandstone VI Lenin

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73417 N 37.60683 E

Sculptor; V.D. Chazov

Blog post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

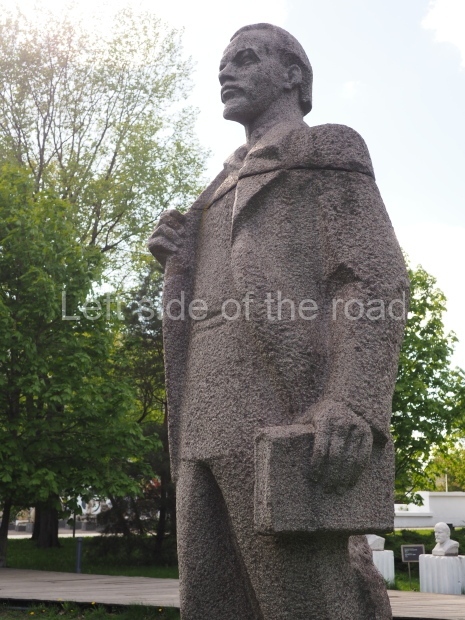

Young VI Ulyanov (Lenin)

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73417 N 37.60677 E

Sculptor; A.I.Toropygin

Blog Post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

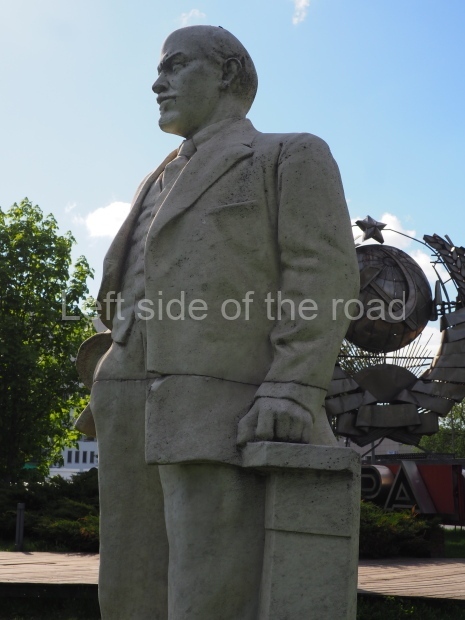

VI Lenin standing, resting hand on pillar

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73422 N 37.60671 E

Sculptor; I.A. Mendelevich

Blog Post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

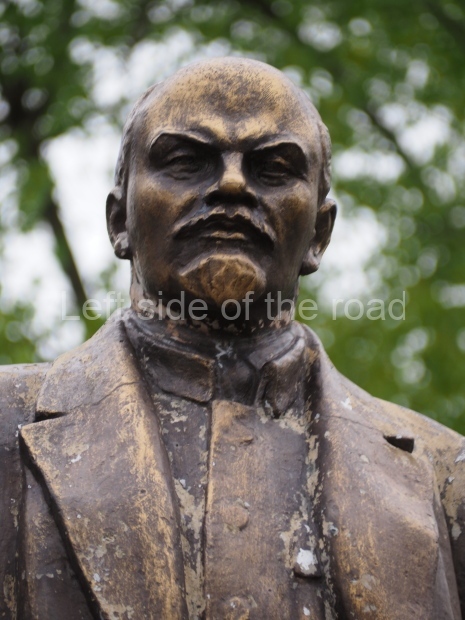

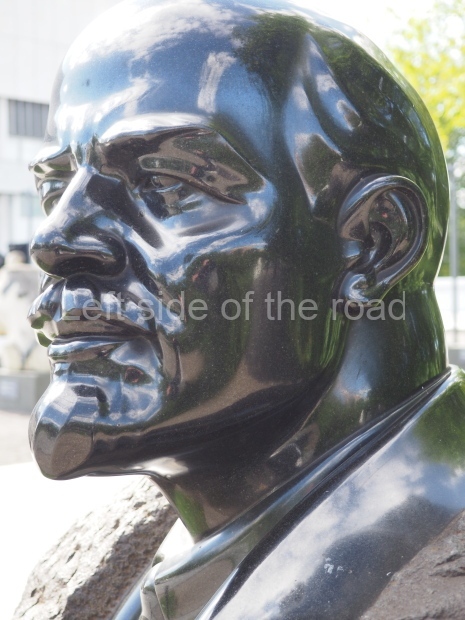

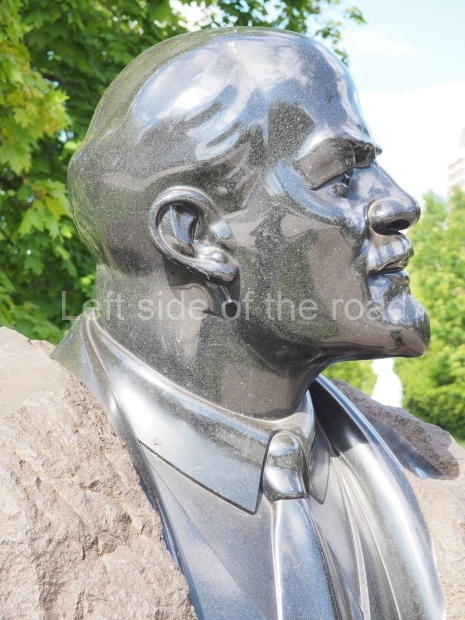

Black, granite bust of VI Lenin

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73420 N 37.60681 E

Sculptor; Sergey Dmitriyevich Merkurov

Notes; Until the early 1990s, the bust stood near the building of the Belorussky railway station.

Blog post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

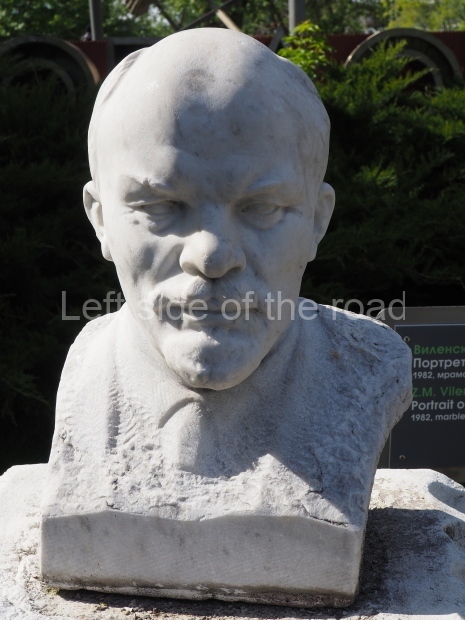

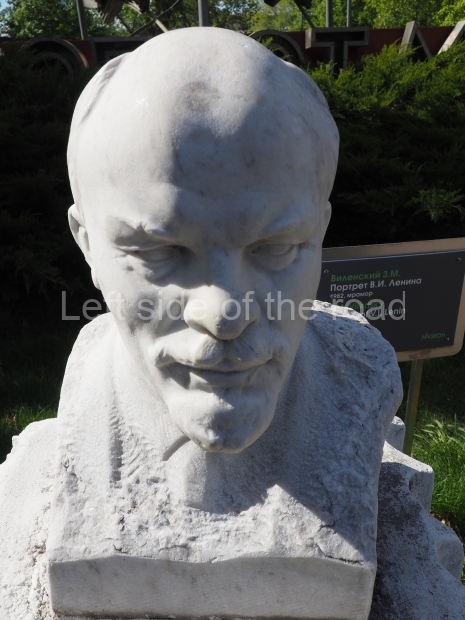

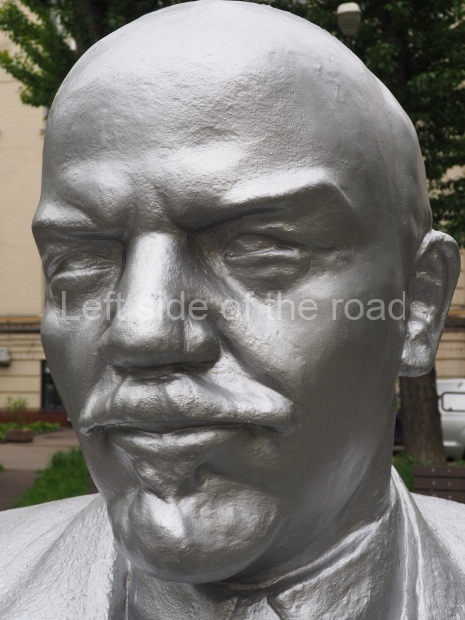

Small, marble bust of VI Lenin

Location; Muzeon Park

GPS; 55.73422 N 37.60680 E

Sculptor; Z.M. Vilensky

Year; 1982

Blog post; Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

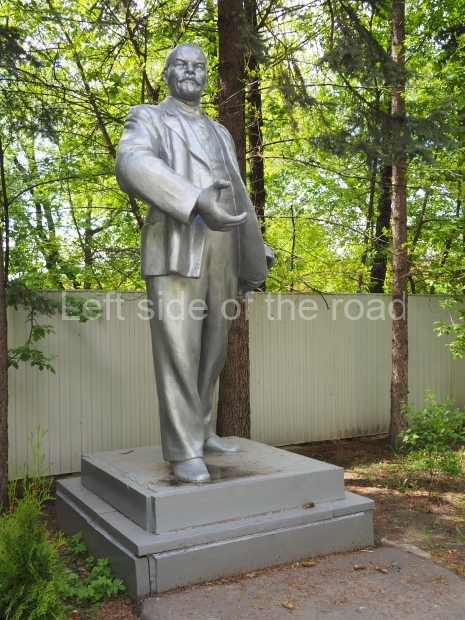

VI Lenin amongst the fir trees

Location; Avtozavodskaya Street, 23

GPS; 55.70402 N 37.63534 E

Sculptors; Yu.P.Pommer, A.A.Stempkovsky

Year; 1956

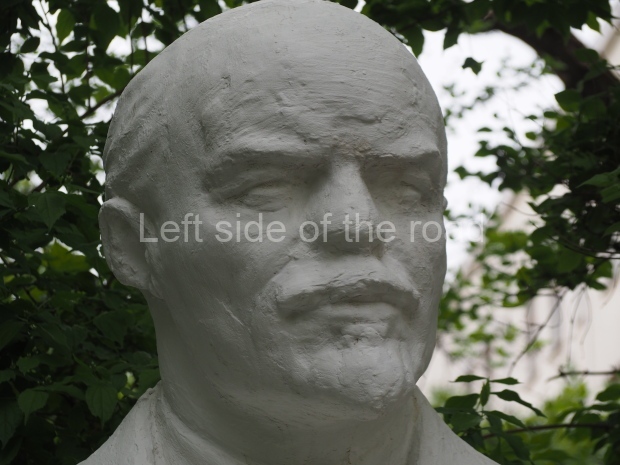

Bust of VI Lenin in residential park

Location; Gruzinsky Val Street, 26

GPS; 55.77416 N 37.58310 E

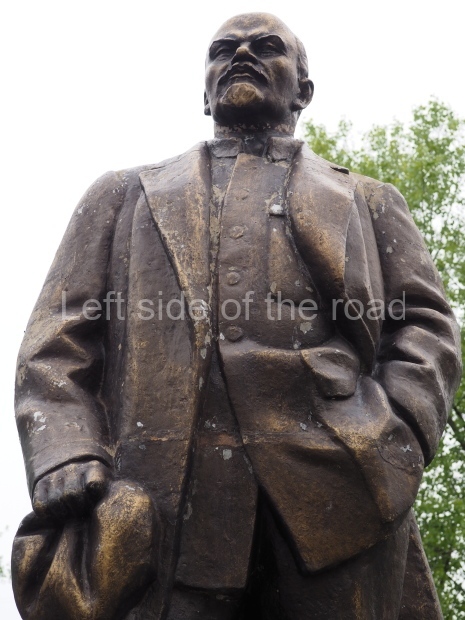

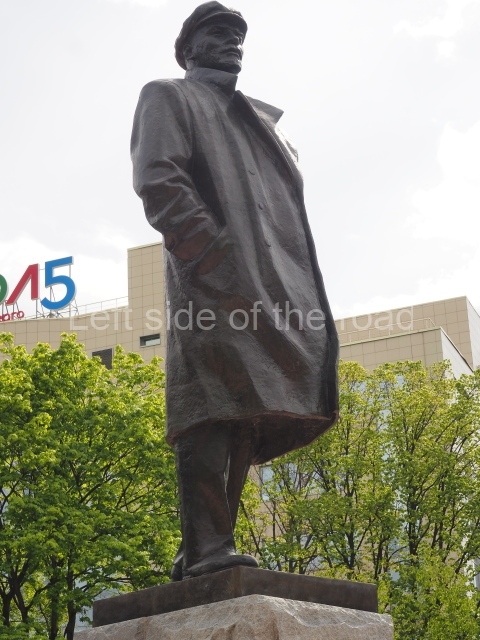

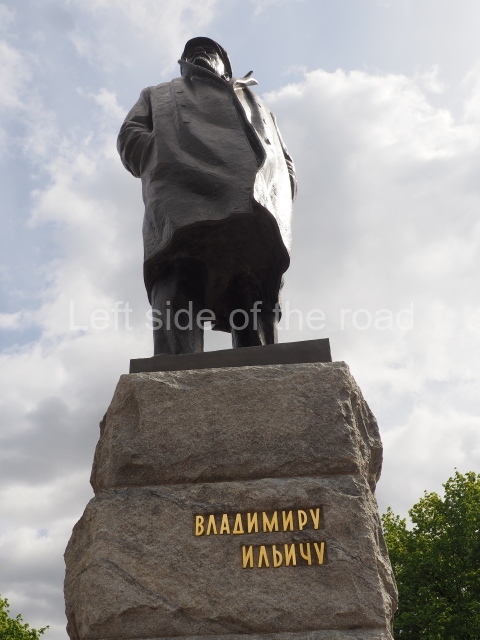

VI Lenin, standing with hand in his pocket

Location; Klimashkina Street, 22

GPS; 55.76838 N 37.56725 E

Notes; On June 7, 2016, the monument was thrown down from its pedestal and broken. Probable causes are vandalism or the action of squally winds. In November 2017, it was restored in its original form.

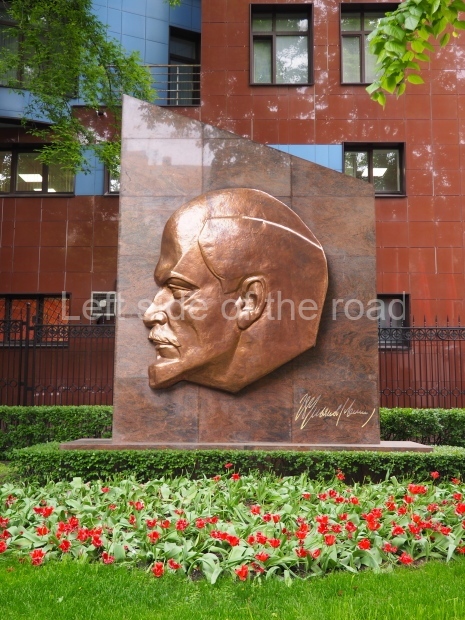

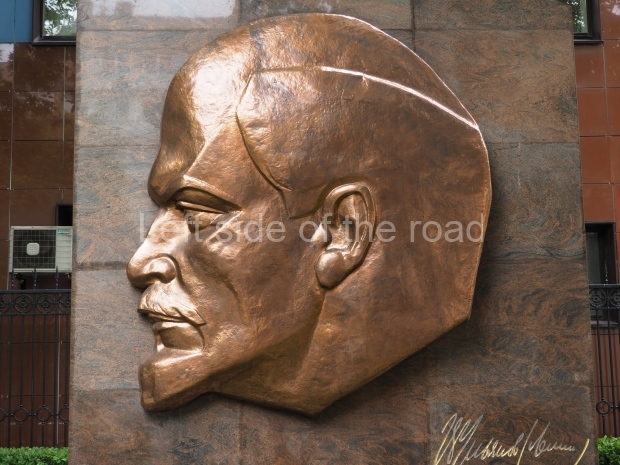

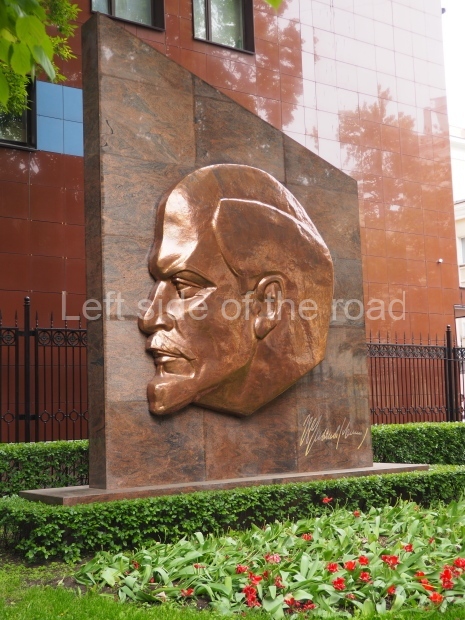

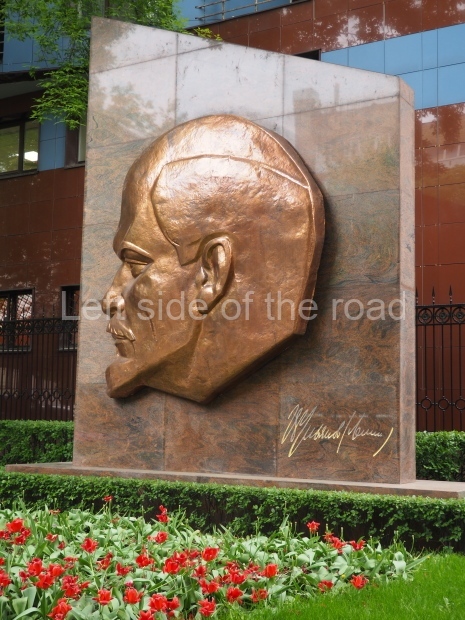

Large bas relief of VI Lenin

Location: Maly Sukharevskaya Lane 7, Headquarters of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

GPS; 55.77052 N 37.62409 E

Bust of VI Lenin in small residential square

Location; Palikha Street 7-9k6

GPS; 55.78513 N 37.59835 E

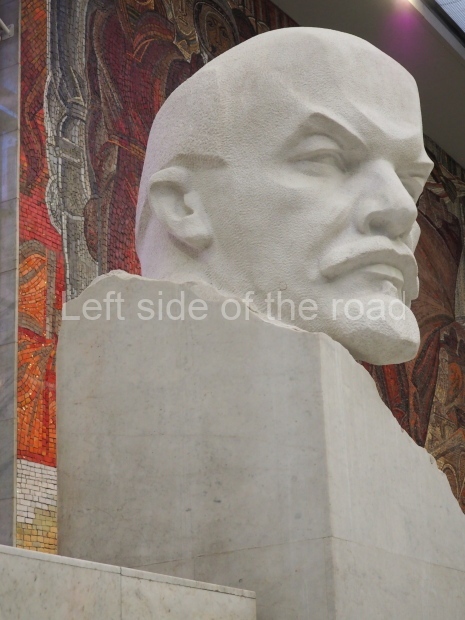

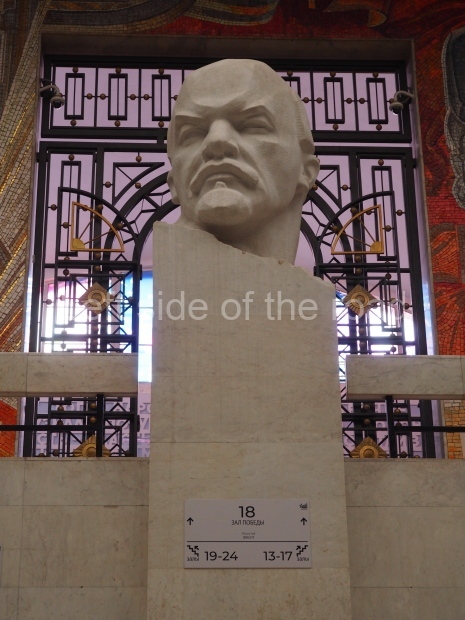

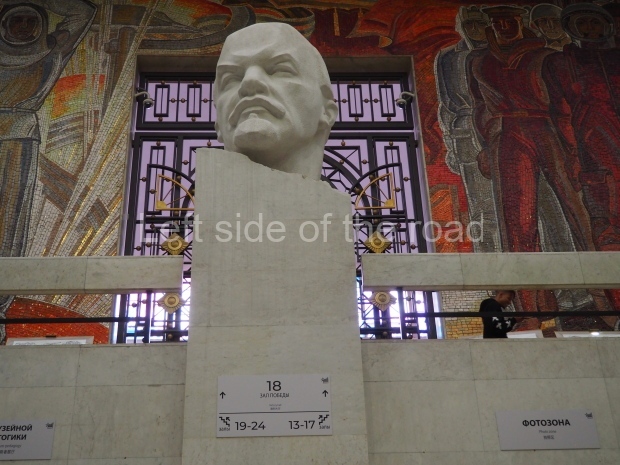

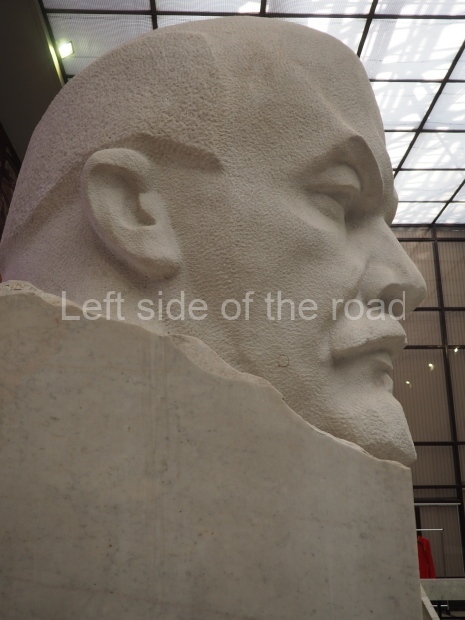

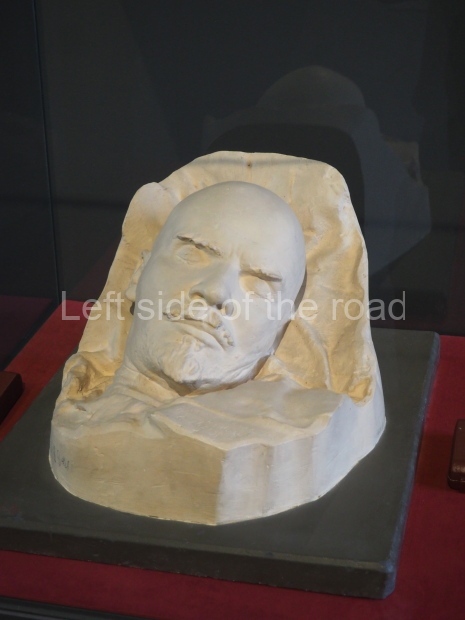

VI Lenin at the Central Armed Forces Museum

Location; Sovetskaya Armii str., 2, facing you, up the first flight of stairs, on entering the Central Armed Forces Museum

GPS; 55.78496 N 37.61721 E

Plaques and bas reliefs

There will be many more throughout the city but here are just a few in central Moscow

Moscow City Hall

Location; Moscow City Hall, Ulitsa Tverskaya 13

GPS; 55.76171 N 37.60905 E

Kievskaya Railway Station

Location; By the main entrance of Kievskaya mainline railway station.

GPS; 55.74366 N 37.56786 E

Museum of Architecture

Location; On the wall at the end of the building on the Museum of Architecture on Vozdvizhenka Street, 5/25

GPS; 55.75263 N 37.60724 E

Hotel Metropol

Location; On the wall to the left of upper entrance of the Hotel Metropol on Teatralnaya Proyezti 2.

GPS; 55.75914 N 37.62194 E

Tverskaya Square

Location; On the top corner of the square, close to the main road

GPS; 55.76147 N 37.60997 E

VI Lenin in the Moscow Metro

Images of VI Lenin can still be found in the Moscow Metro system, either busts or mosaics. These include in;

Baumanskaya – Line 3, mosaic at platform level

Belorusskaya, bust in the vestibule

Biblioteka Imeni Lenina, large mosaic at the top of the stairs to the platform

Dobryninskaya – Line 5, large mosaic at the top of the escalators

Kievskaya – Line 3, in various mosaics on the platform level

Kievskaya – Line 5, in various mosaics on the platform level

Komsomolskaya – Line 5, a bust at the end of the platform and in various mosaics

Novokuznetskaya – Line 2, mosaic at the end of the platform

Ploshchad Ilyicha – Line 8, bust/high relief at platform end