Toniná – Chiapas

Location

With its privileged location overlooking one end of the Ocosingo Valley, Toniná became one of the great Maya capitals of the Classic period. Situated near the western border of the Maya area, in the transitional area between the low rainforest regions and the cold forests of the Chiapas central plateau, its position enabled it to play a crucial role in the trade relations with other territories. Between the 7th and 10th centuries AD, its political alliances and military advances earned it the status of an important regional power. The site lies 10 km east of the town of Ocosingo, easily reached on route 199.

Site description

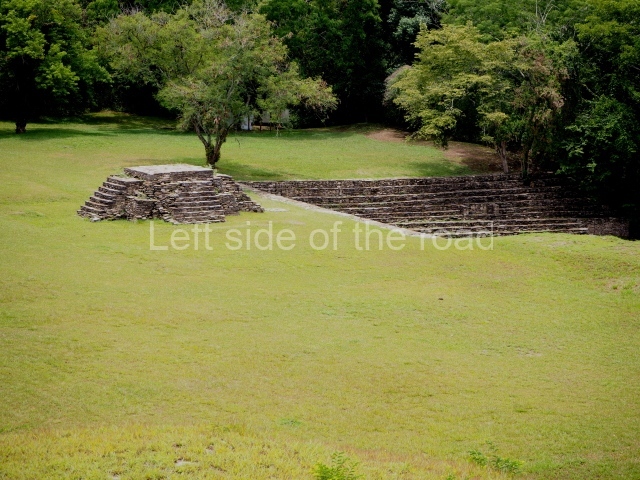

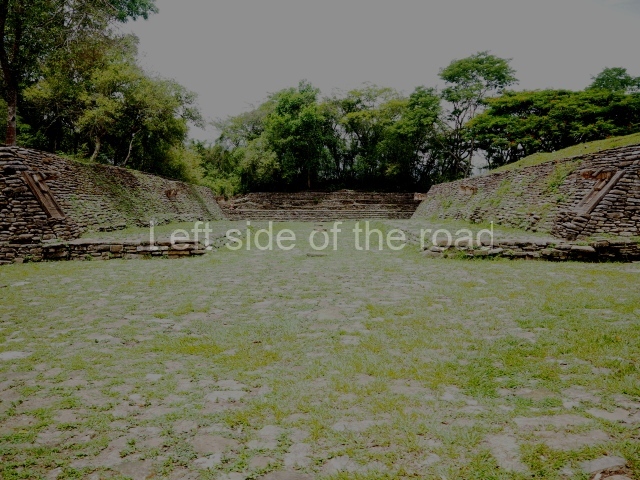

The tour of the site commences by crossing a small stream and then climbing up to the large playing area of the sunken, I-shaped ball court. The ground of the playing area is covered by stone slabs which originally had a top layer of stucco, and there are several circular stone markers where offerings of sea shells with a red pigment and jade beads were found; seating areas for spectators seal both ends of the court. The sloping volumes of the parallel platforms were surmounted by imposing sculptures of prisoners, three on each side. One of these is currently on display at the site museum. The sculptures consisted of a large shield interwoven and fringed with feathers carved in bas-relief on a panel; projecting from the latter was the three-dimensional body of a kneeling prisoner with his hands tied behind his back. Thanks to the information recorded in the hieroglyphs, we know that this court was dedicated in AD 699 to celebrate the success of the military campaigns conducted by the governor B’aaknal Chaak in the Usumacinta region, and that it was subsequently remodelled in AD 776; the prisoners, who have been identified by their glyphs, were vassals of Palenque, Toniná’s eternal rival.

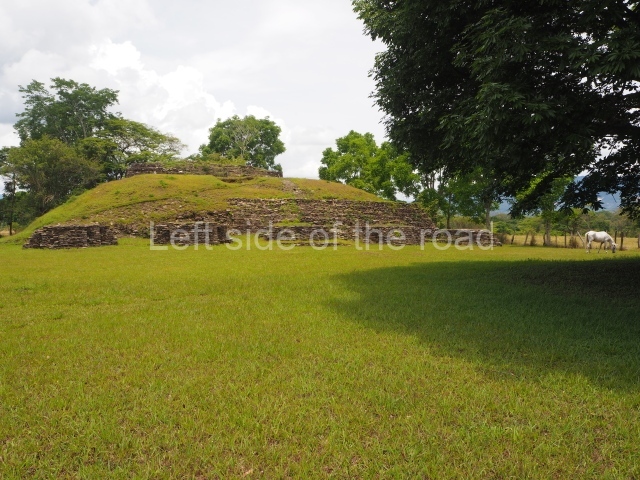

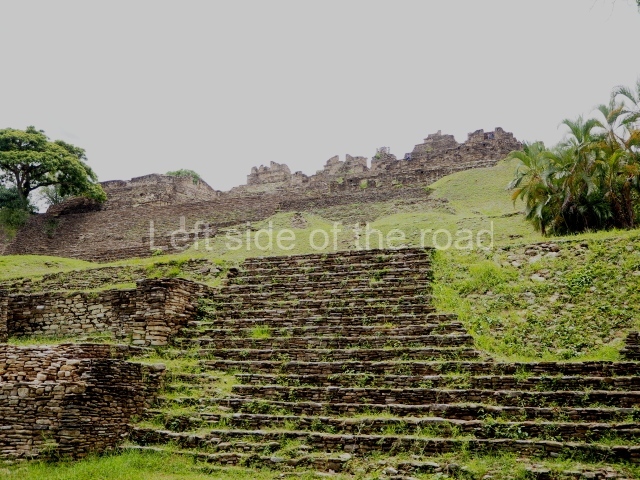

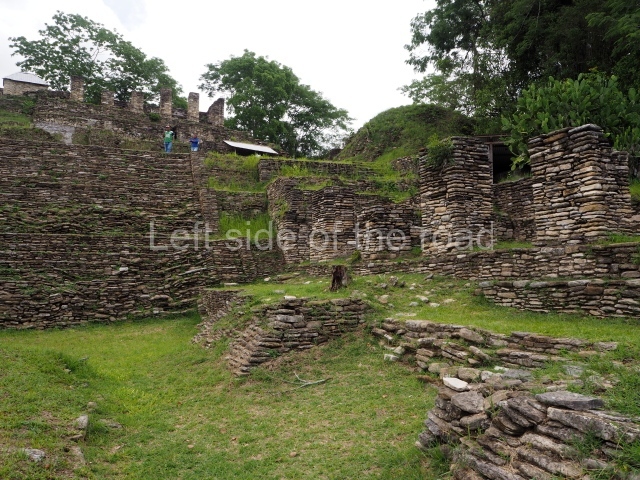

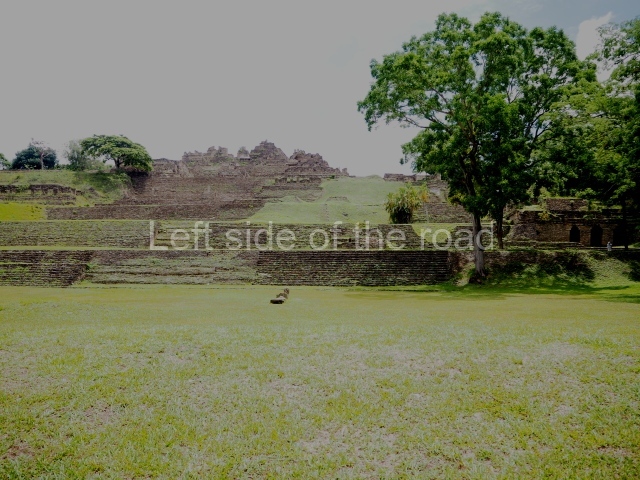

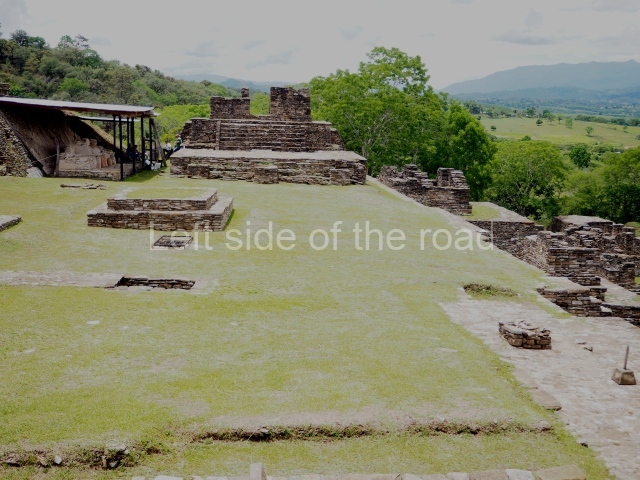

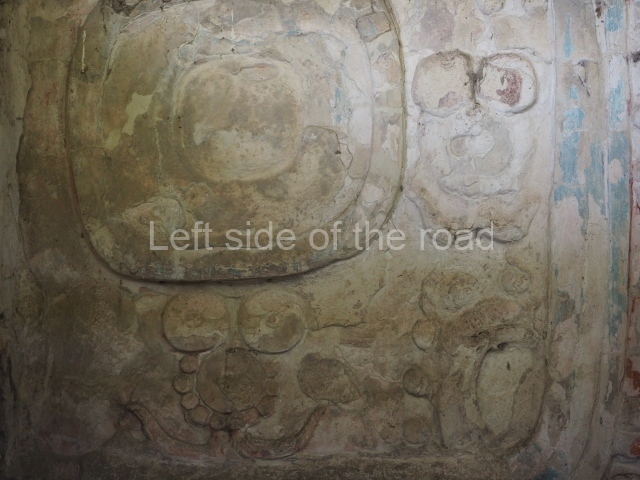

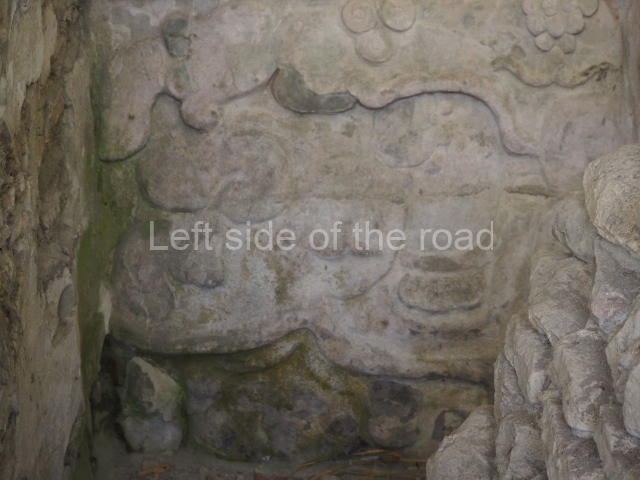

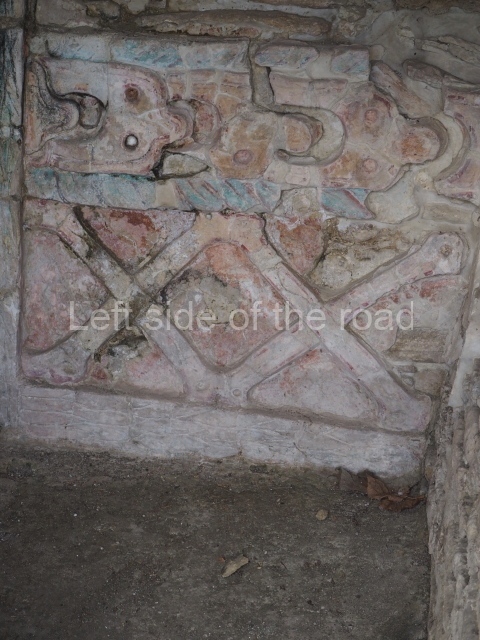

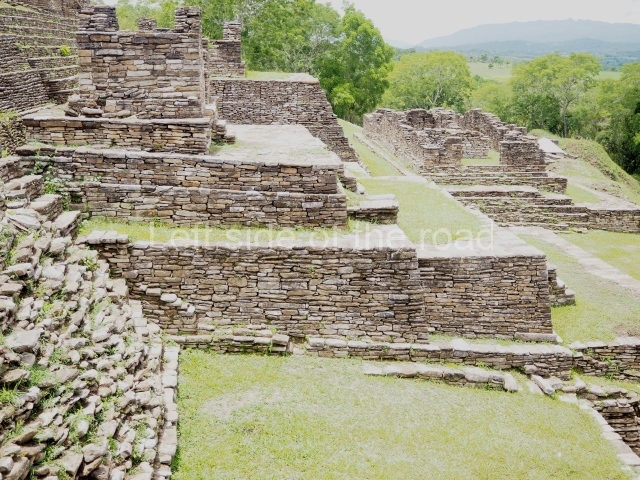

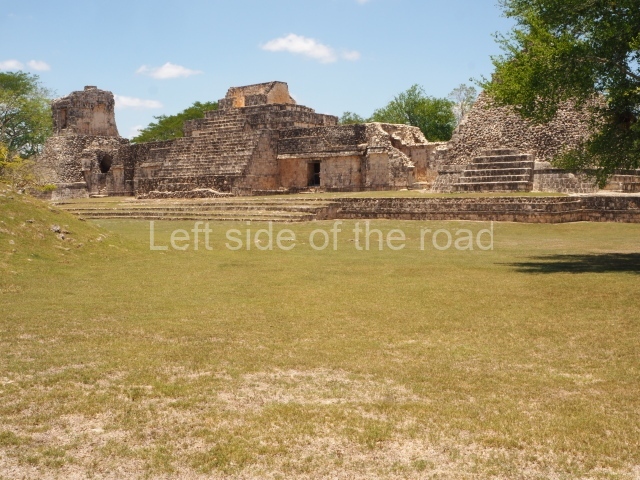

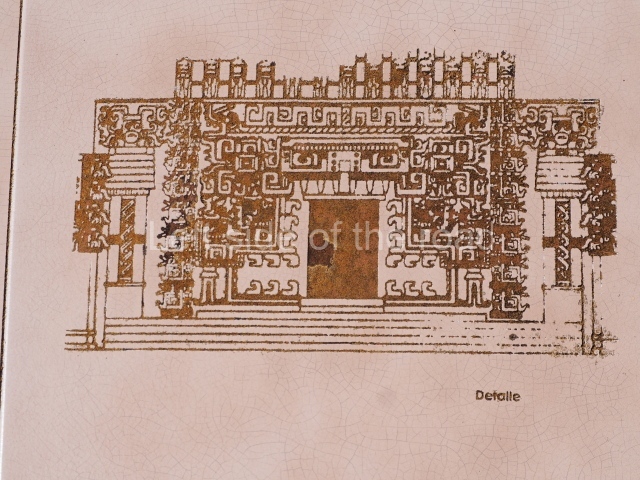

On leaving the ball court, you come to the great plaza and, at its north end, the great acropolis of Toning, the core political and ceremonial area of the city built on seven platforms rising from the natural elevation of a hill. On the opposite side of the plaza, along the south side, is a temple-pyramid known as the Temple of war, with five small altars in front of it. Evidence has been found in the Acropolis of numerous platforms, temples and richly decorated palaces, as well as tombs and sculpted monuments, all of which indicates intensive building activity over the course of several centuries. The local architectural style is easily distinguished by the slender slabs of stones, cut into square blocks, which were used for building walls, stairways, vaults and roof combs; the slabs were bonded with a clay mortar and then covered by thick layers of lime stucco. Meanwhile, the facades, friezes and walls of the constructions were often elaborately decorated with modelled stucco and painted, and although this material does not weather well, several examples have survived to this day and provide us with an insight into what the city must have looked like. The sculptural style at Toniná displays characteristics that have not been found anywhere else in the region, most notably manifested in the numerous exquisitely crafted images of governors and prisoners, carved in the round in the local sandstone and accompanied by hieroglyphic texts, although there are also magnificent examples of bas-relief carvings on panels and altars.

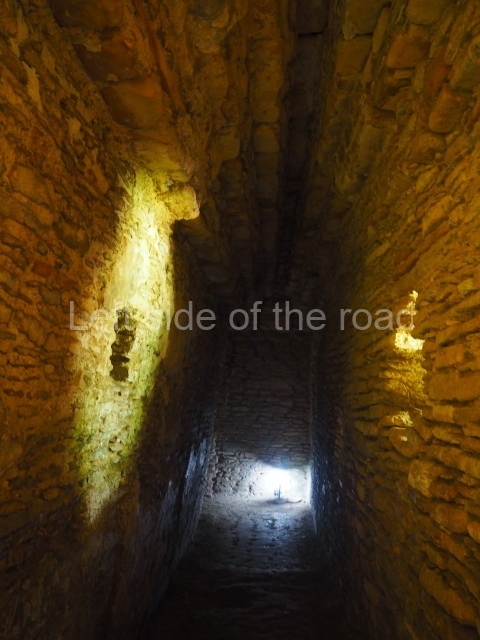

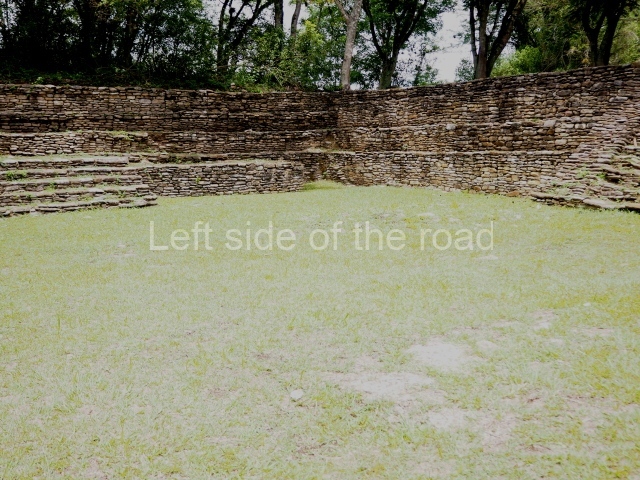

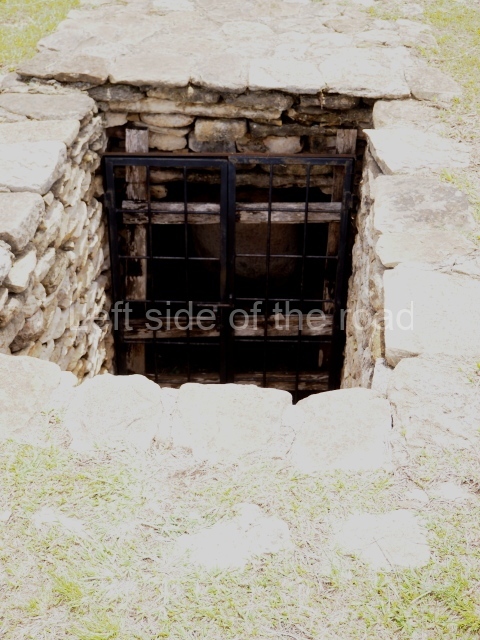

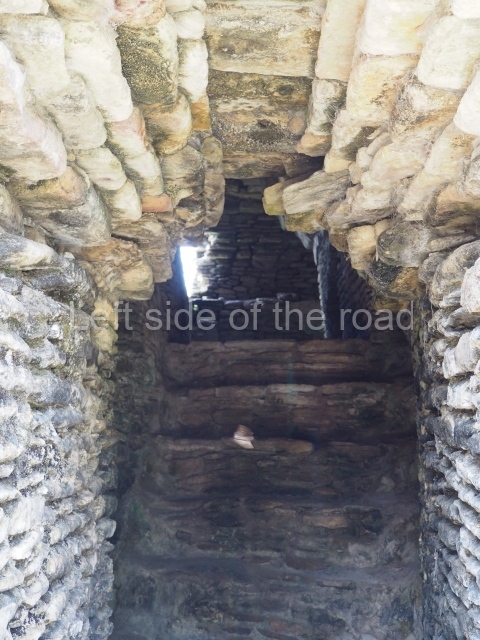

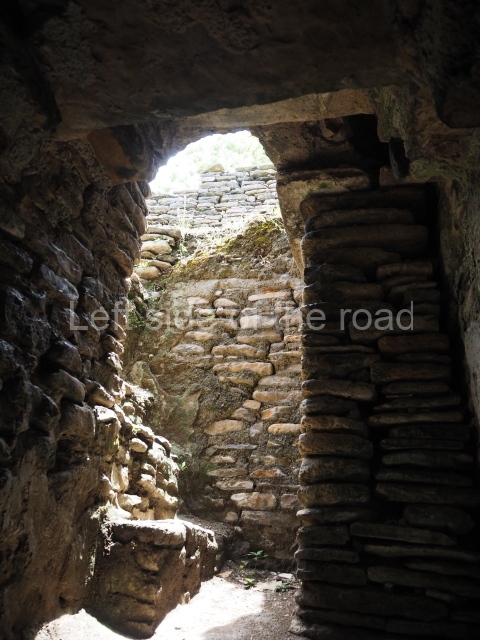

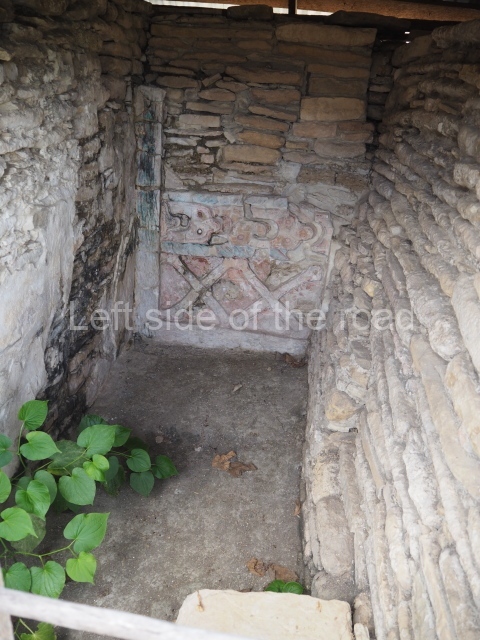

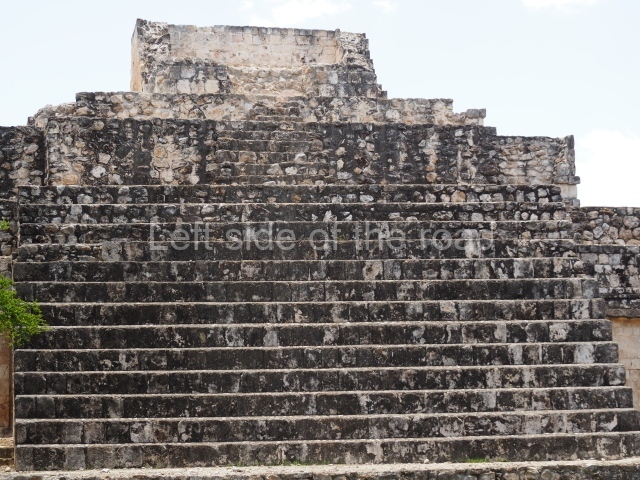

As you climb up to the different levels of the Acropolis, you will have the chance to discover different types of precincts and constructions. Situated at the east end of the first platform is the Palace of the Underworld. This is the sub-structure of a palace composed of 11 bays or vaulted passages which are accessed on the south side only, via three doors with a lintel and stepped vault. The layout is not symmetrical but forms a type of labyrinth in which the passages become increasingly narrower and darker; the only source of light comes from two small cross-shaped openings on the south facade of the palace. Structures of this type may have been associated with initiation rites for governors, during which contact was established with the gods or the governor’s ancestors through bloodletting rituals, and they may therefore have represented a symbolic entrance to the underworld. Other examples of pre-Hispanic labyrinths have been recorded at Yaxchilan, in the Usumacinta region, and at Oxkintok, Yucatan. Situated on the third platform is an imposing stepped fret, the symbol of the wind, and next to it a short free-standing stairway culminating in a throne decorated with hieroglyphs, leading to the palace area. The entire eastern section of the Acropolis, which is not open to visitors, was used throughout several dynasties as the residential area for the local elite, marking a clear division from the western section which appears to have been used for administrative and/or public affairs. In general, the different palaces adopt a similar layout, with the rooms opening onto a central quadrangular courtyard. The rooms were originally ornately decorated with polychrome stucco reliefs depicting historical and mythological scenes. The central part of the fifth platform was probably a necropolis because several tombs of important dignitaries, possibly members of the ruling class, have been found in this area. On the seventh and final platform of the Acropolis are several pyramid temples from the top of which visitors will gain panoramic views of the valley. The best preserved structure is the Temple of the earth monster, thus called because the middle of the stairway was decorated with a giant, open-mouthed mask with a stone sphere inside, possibly representing the sun emerging from the underworld at dawn. In this temple it is possible to see how the stepped vault resting on thick masonry walls was built, culminating in a perforated roof comb reminiscent of the Usumacinta style; another interesting element is the presence of an adoratorium inside a second bay, not unlike the ones in the Cross Group at Palenque. At the beginning of the 10th century AD, during the Chenek phase, the site was affected by the Maya collapse and the widespread abandonment of the Maya lowlands; there are clear signs of the arrival of foreign groups who settled at the site, looting the tombs and destroying the sculpted monuments.

Lynneth S. Lowe

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp453-459.

- Great Plaza; 2. Ball Court; 3. South Temple; 4. Great Acropolis; 5. Palace of the Underworld; 6. Palace of the Jaguars; 7. Mural; 8. Temple of War.

Getting there:

From Ocosingo. Colectivo to Toniná from Azucena/Periférico Oriente Sur, in the middle of the busy market area. M$25 right to the site entrance. If there is a delay in a return combi walk back up the road a kilometre to the next junction. Here there are all kinds of transport options going back to Ocosingo, just flag down everything that passes.

GPS:

16d 54′ 07″ N

92d 00′ 34″ W

Entrance:

It displays an entrance of M$75 but I wasn’t charged. There’s a labour dispute (summer 2023) so that might account for it.