Chinkultic – Chiapas

Location

This important Maya capital is situated very close to the Montebello National Park, 50 km south-east of the city of Comitan de Dominguez, in the municipal district of La Trinitaria, Chiapas. It can be reached by taking the federal road that leads to the Montebello Lakes, the descent to the River Santo Domingo and the Lacandon Rainforest. The region boasts a mild climate and is geographically composed of wide valleys, lakes of different shades and low mountains (1,600 m above sea level), covered with pines and fir trees, which alternate with forests of oaks and low evergreen rainforest; due to the excessive humidity in the atmosphere, the trees are covered with a rich variety of epiphyte plants, such as magnificent wild bromelias and orchids, as well as offering a sanctuary to quetzals and other endangered species.

Pre-Hispanic history

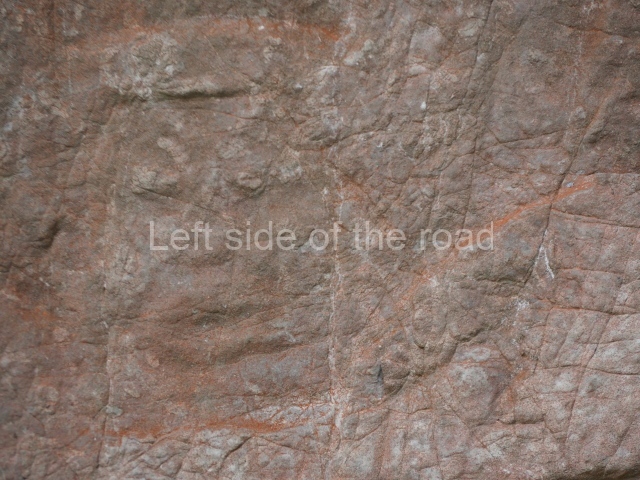

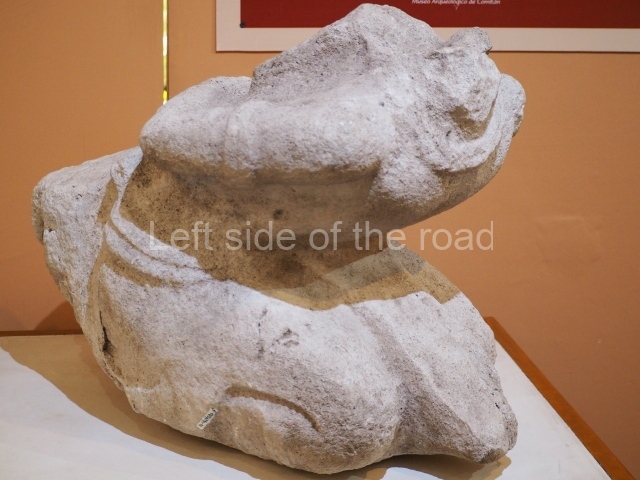

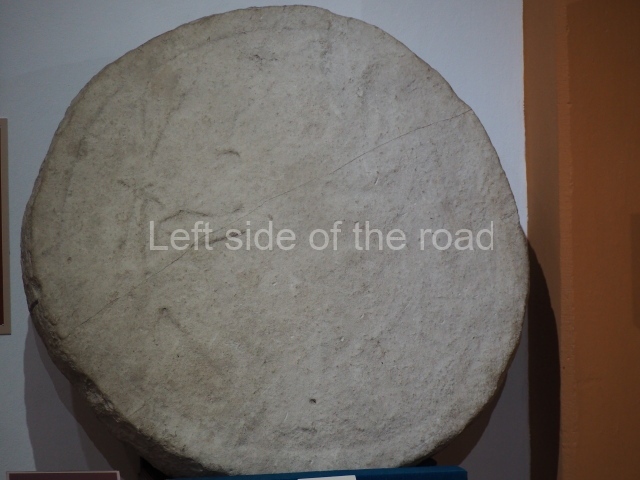

The human settlement emerged in the Late Preclassic (400 BC-AD 250), as evidenced by five fragments with reliefs dated to that period, with activity concentrated around the Mirador (Group A). Subsequently, the dates on the monuments correspond to the beginning of the Early Classic, as in the case of the Disc of Hope or Chinkultic Disc (AD 573), and there is a hiatus in the epigraphic records until 9.18.0.0.0 or AD 790 (Stela 8); the last date is 10.0.15.0.0 (AD 844), inscribed on Stela 1. After this time there appears to have been ritual activity at the Mirador Group, judging from the Early Postclassic (AD 1000-1200) offerings discovered by Pierre Agrinier; later on, there is little evidence of occupation during the Late Postclassic and the worship of ancestors and the gods of the underworld seems to have been confined to caves and caverns, greatly abundant in the area due to the limestone subsoil.

Site description

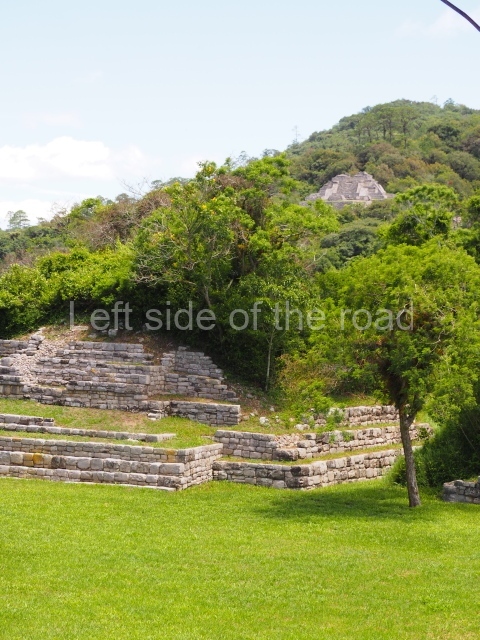

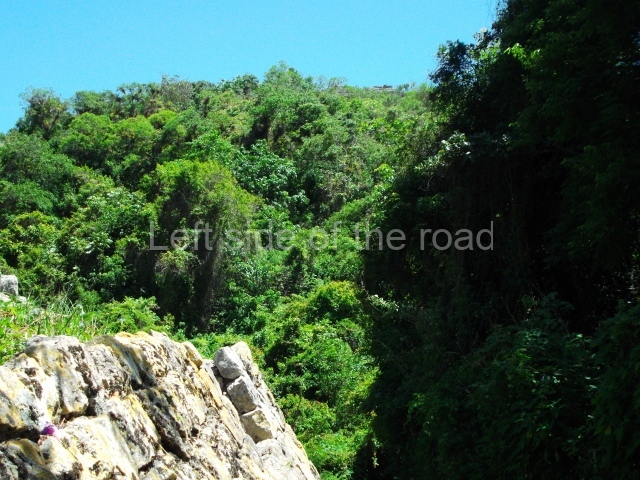

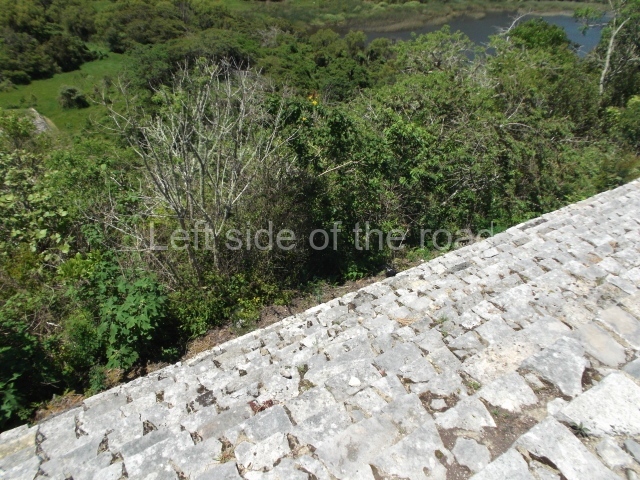

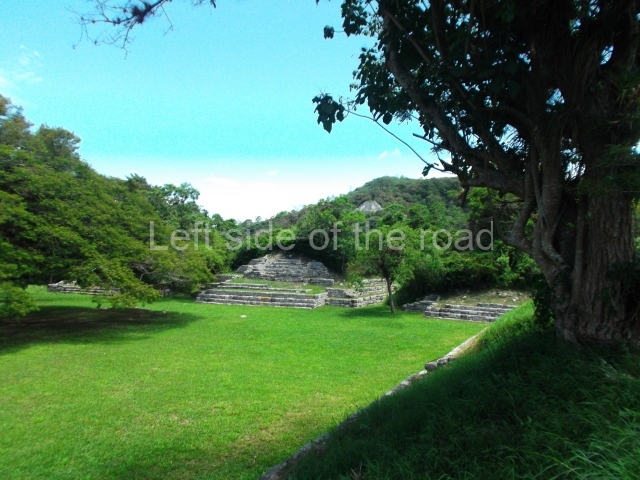

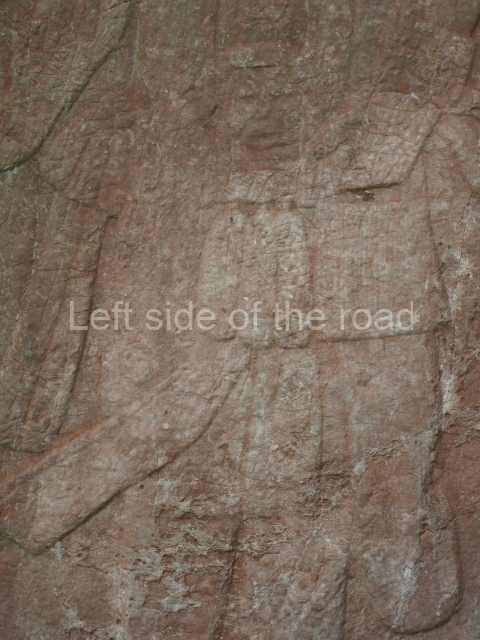

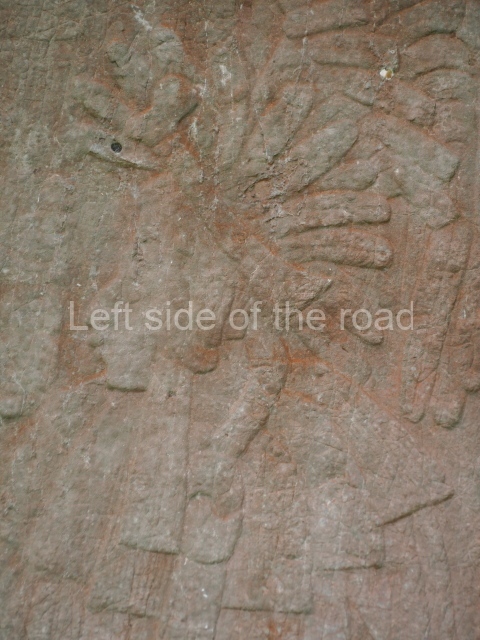

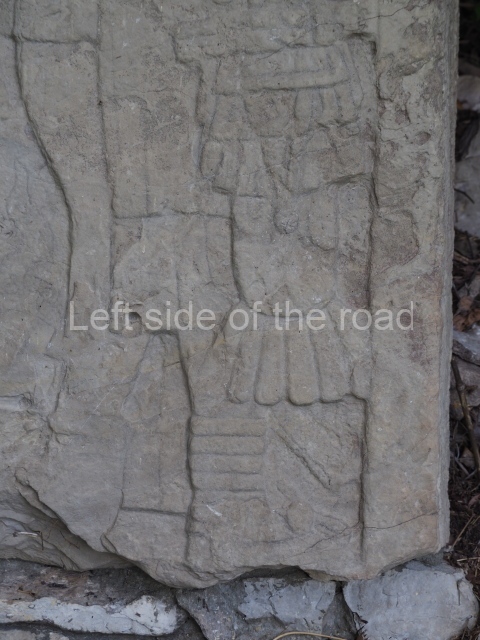

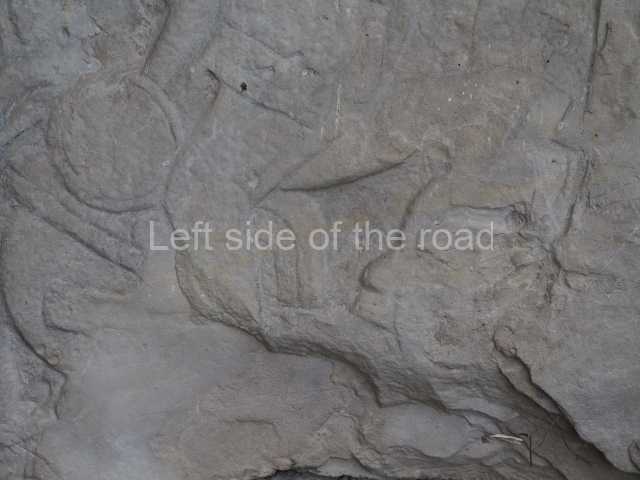

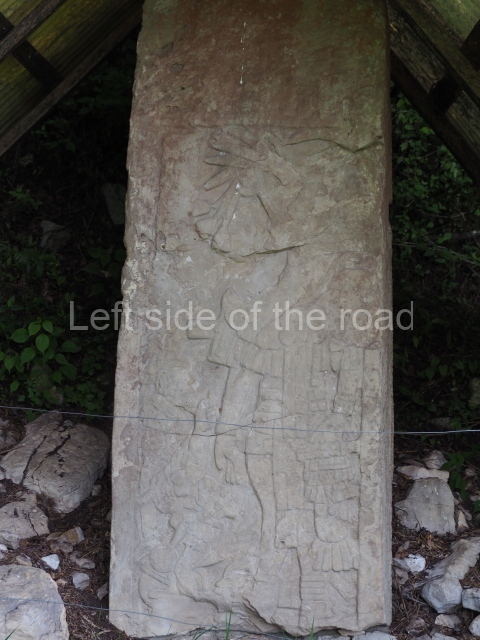

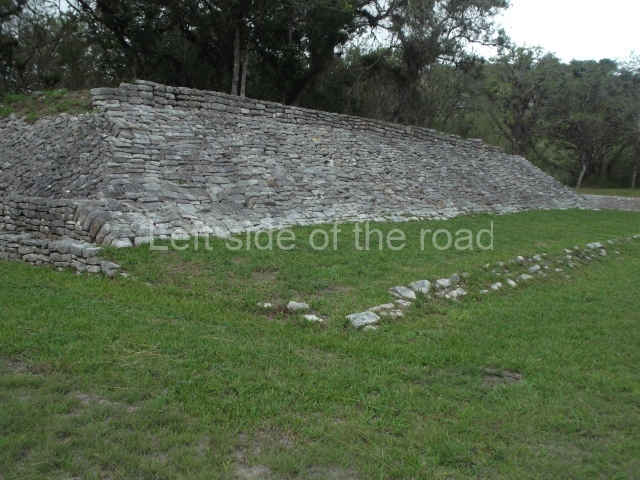

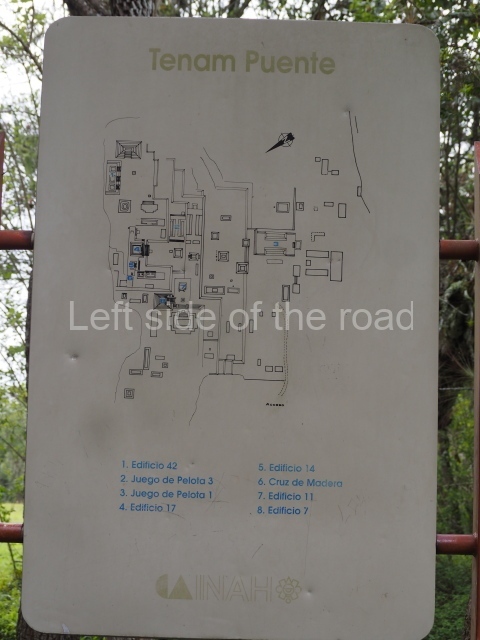

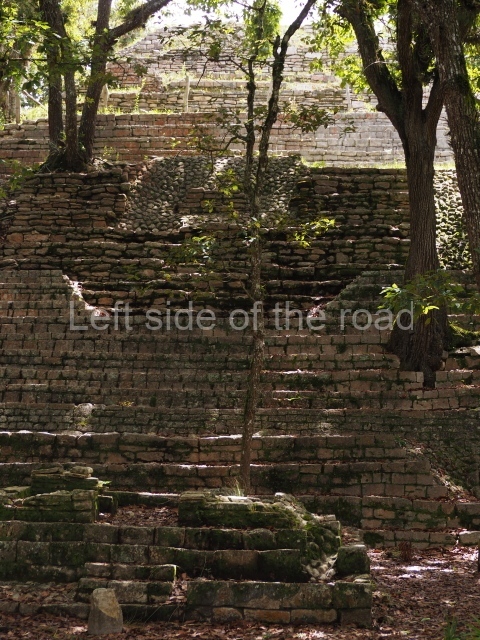

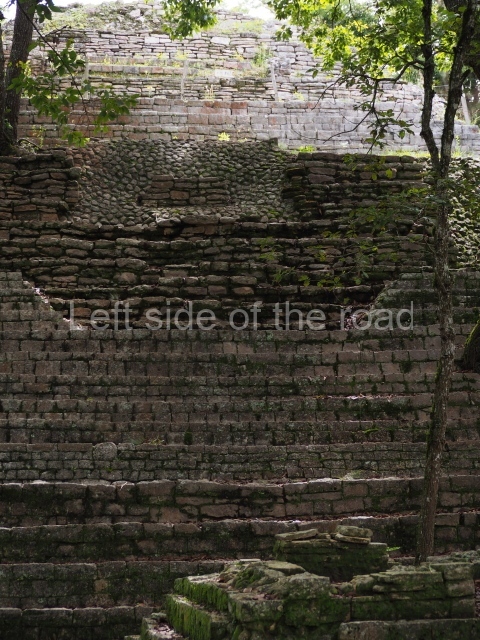

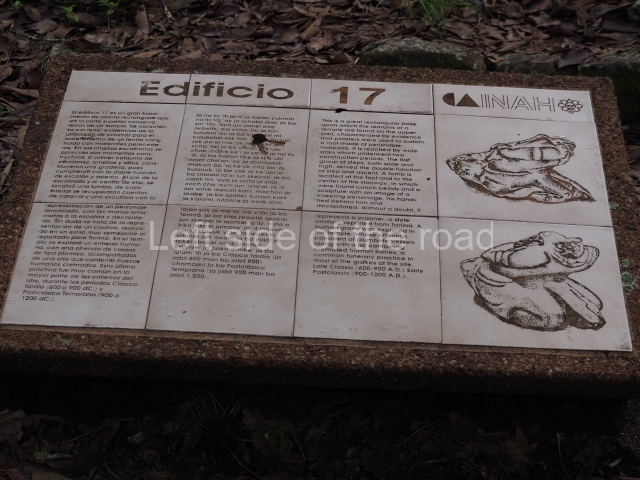

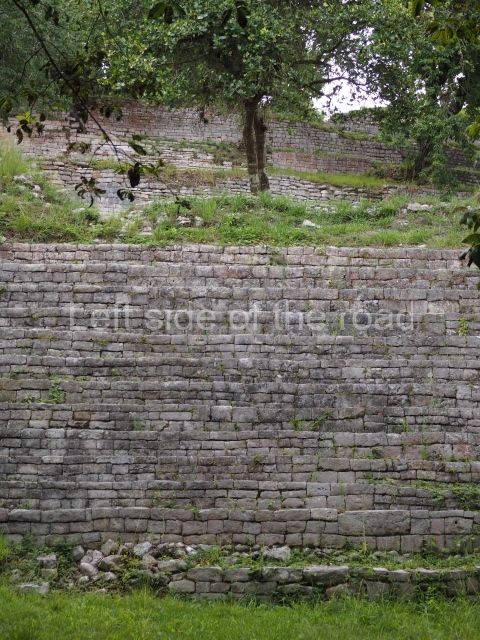

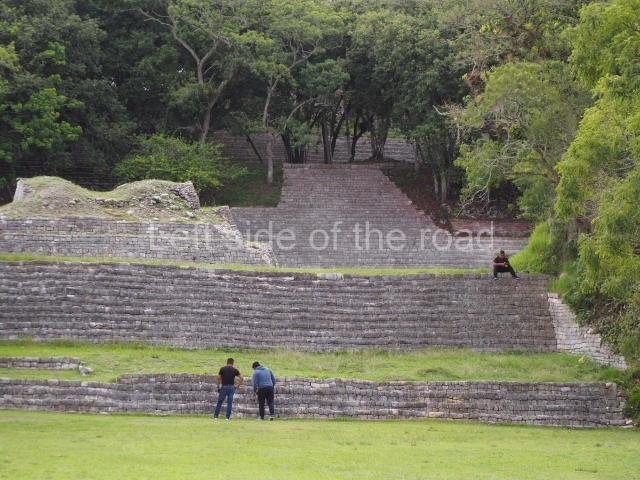

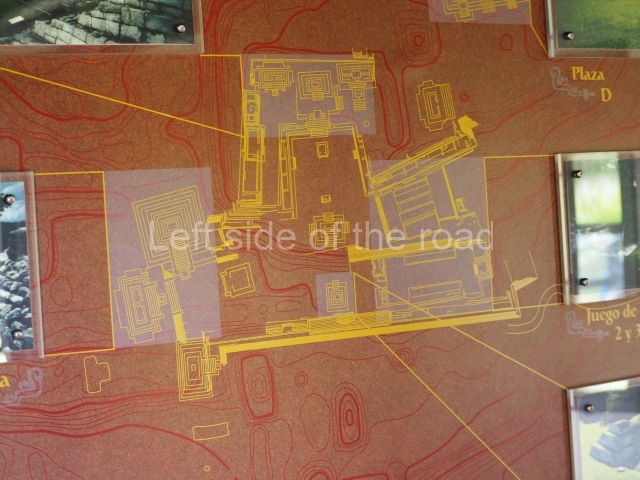

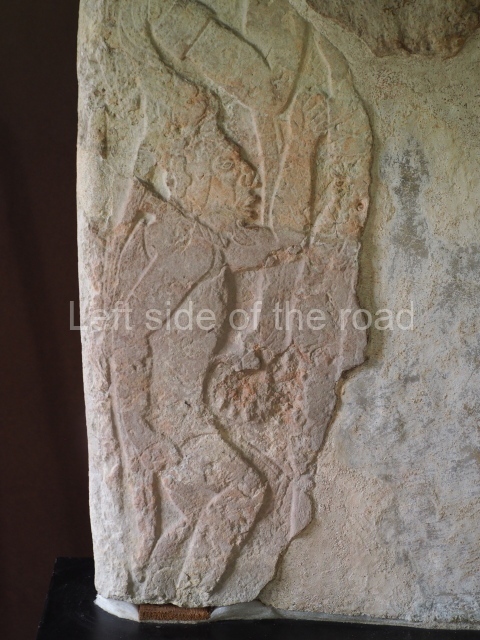

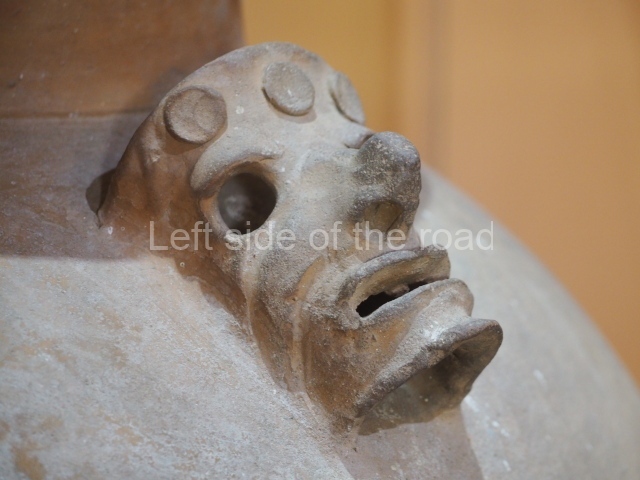

The archaeological area is situated on the Rincon estate, part of the old Tepancuapan Hacienda which has now been divided up into several farming communities. During pre-Hispanic times, this area was densely populated and covered several square kilometres branching out from the civic-ceremonial centre and the Agua Azul cenote, in the zone locally known as La Bolsa. Extending over large areas are the ruins of secondary groups with pyramidal structures and ball courts, as well as the remains of residential constructions on low platforms, made of stucco-clad stone masonry and surrounded by handsome lakes. The site is situated opposite the Hidalgo colony and is reached by an asphalt road. The civic-ceremonial centre at the settlement, composed of approximately 200 mounds of varying sizes, extends over some 40 ha, although the groups of constructions are relatively scattered and display a certain integration between the architecture and the landscape. For the purposes of analysis, the core area of Chinkultic was divided into five groups known by the letters A to E. The River Yubnaranjo, which connects lakes Tepancuapan and Chanujabab, divides the site into two sections. In the northern section, the steep slope of a hill delimits the Agua Azul cenote and has a large 1000-step monumental stairway leading to the main group, called the acropolis or Group A. On the small hilltop, an architectural group was built comprising a pyramidal platform in which it is possible to distinguish two construction phases, another smaller platform, three small altars opposite the monumental stairway and another altar abutted to the lower steps of the pyramid. Two of these altars yielded tombs with offerings of ceramic vessels from the beginning of the Early Postclassic (c. AD 1200). A stela (Monument 9) was also erected opposite the pyramidal platform; although nowadays fragmented, it is possible to make out a richly garbed dignitary wearing a prominent headdress in the fashion of a hat, plus six eroded glyphic cartouches. Behind the architectural complex lies the crystalline Agua Azul cenote, some 50 m deep.

At the foot of the monumental stairway is another semi-enclosed plaza with two pyramidal structures, a small platform that possibly served as an altar and a low, elongated platform near the edge of Lake Tepancuapan. On the wall of the north side of the smaller platform, Agrinier identified a fragment from an early stela reused as a building stone. Situated on the steep slope descending from the Acropolis to the edge of Lake Chanujabab, on an embankment, are another medium-sized pyramid and several low mounds, possibly corresponding to the remains of dwellings: these constructions are known as Group E.

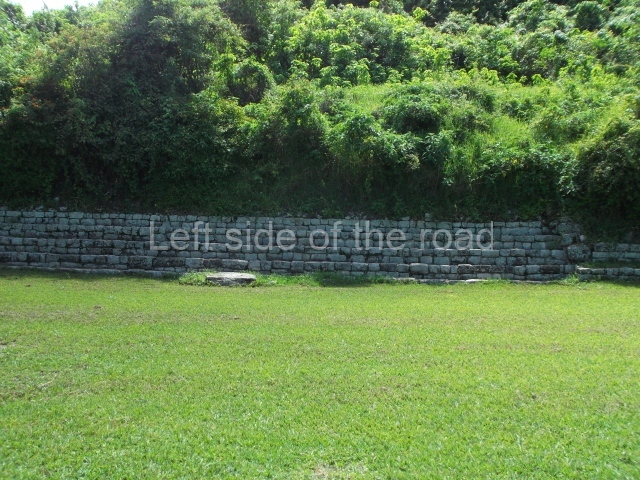

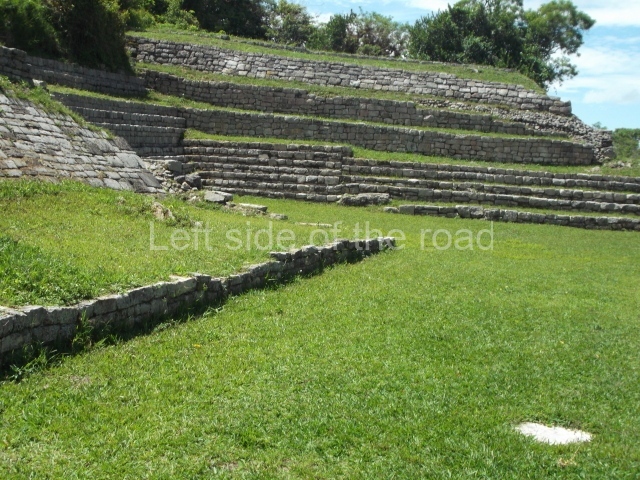

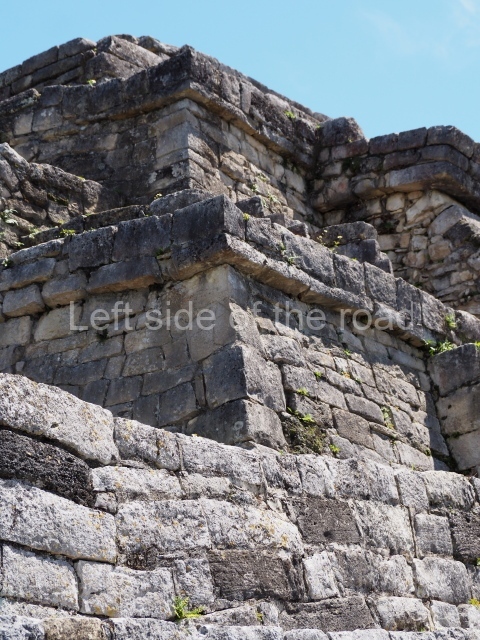

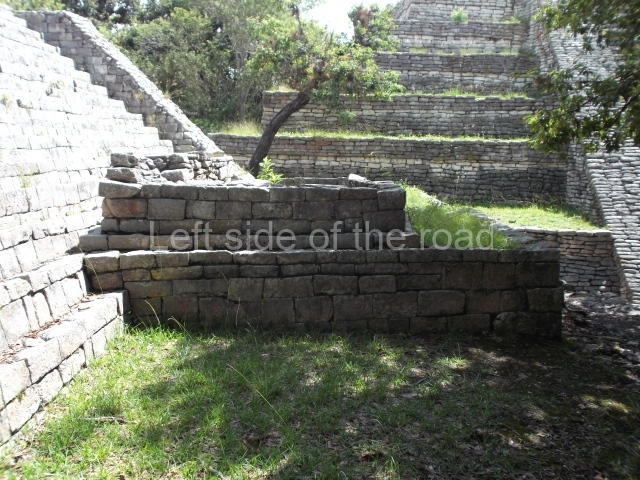

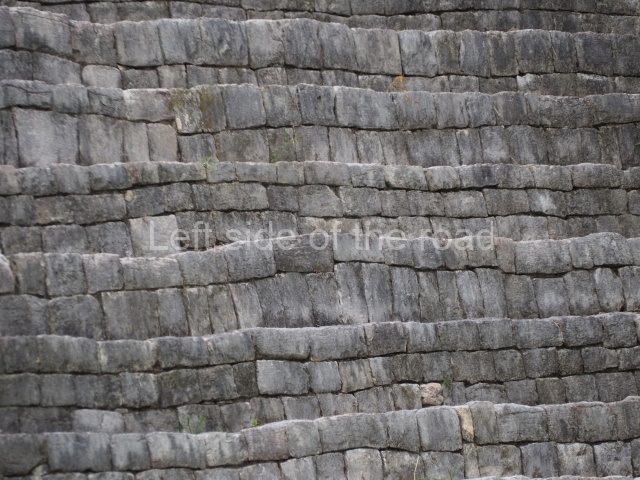

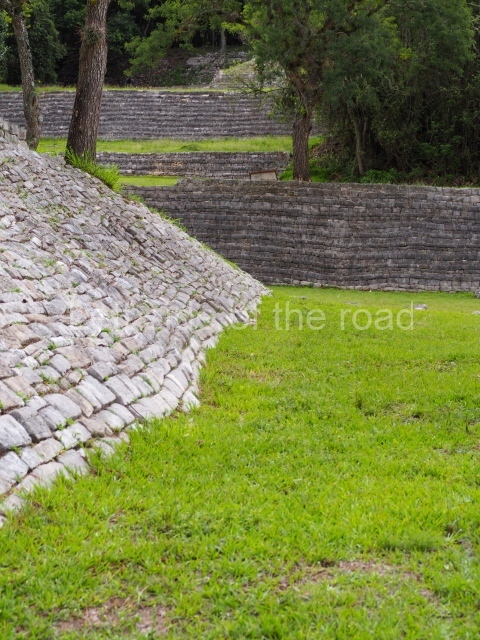

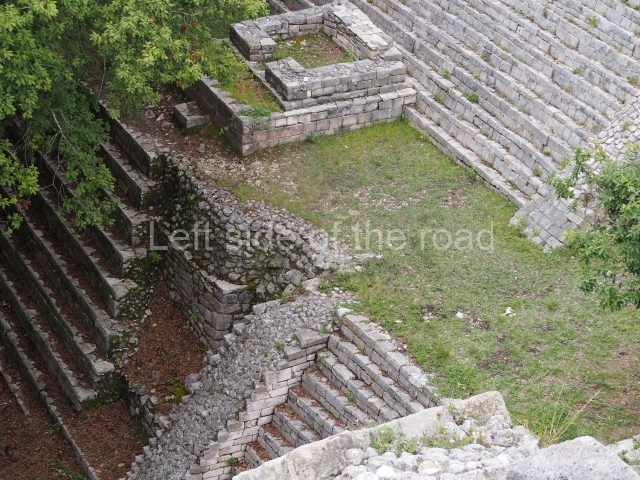

Immediately south of the River Yubnaranjo is Group B, which consists of a stage-like structure comprising a vast seating area made of large blocks of stone; the plaza is delimited on three sides by three large pyramids which stand some 10 m high, and at the centre is a sloping altar with a cornice, which like the pyramid in Group A displays two construction phases. In the upper middle section of the seating area is what appears to be the governor’s box, with several cylindrical altars made of limestone. Towards the south of this element lies a small courtyard (Group D ) delimited by the most important structure at the site, the Pyramid of the Slabstones, built out of ingeniously assembled giant blocks of stone, each several tons in weight.

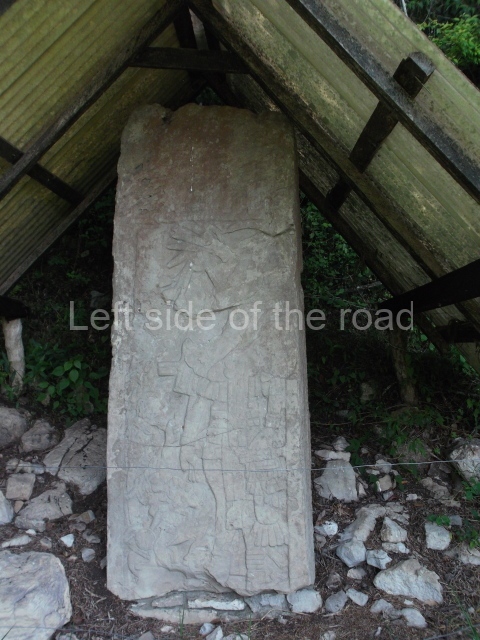

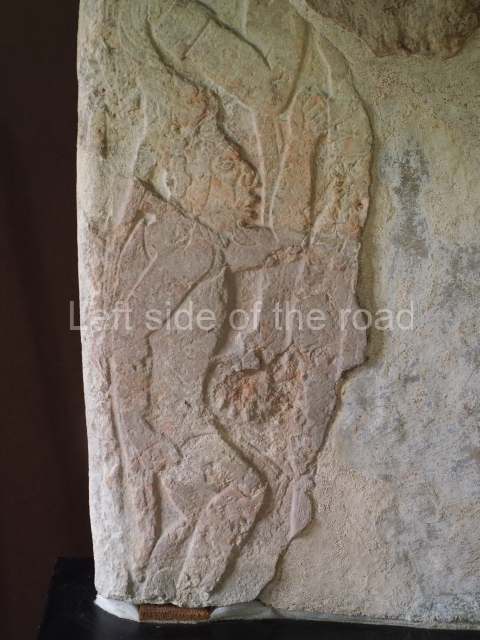

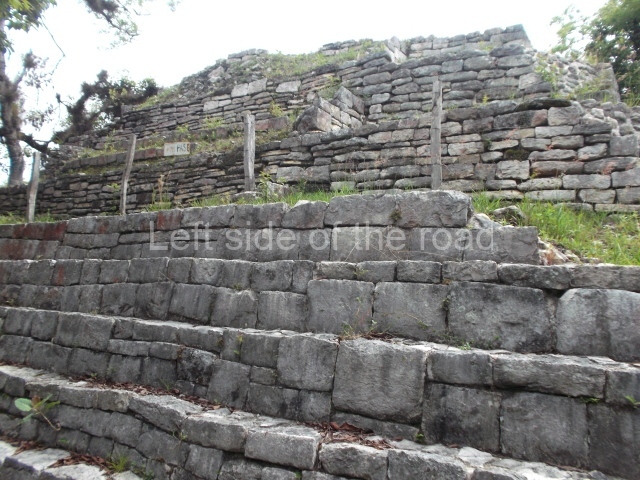

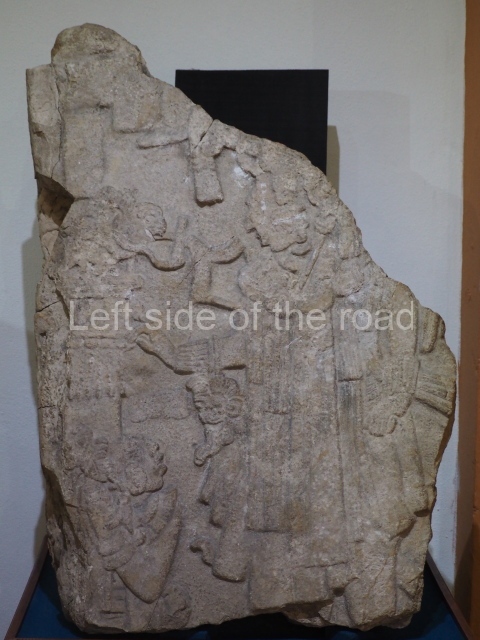

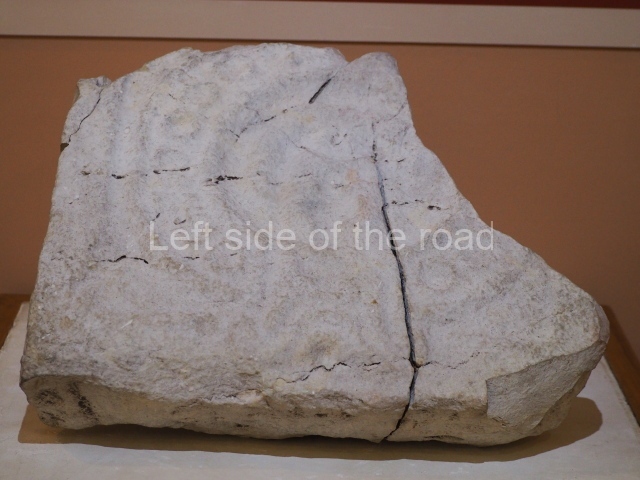

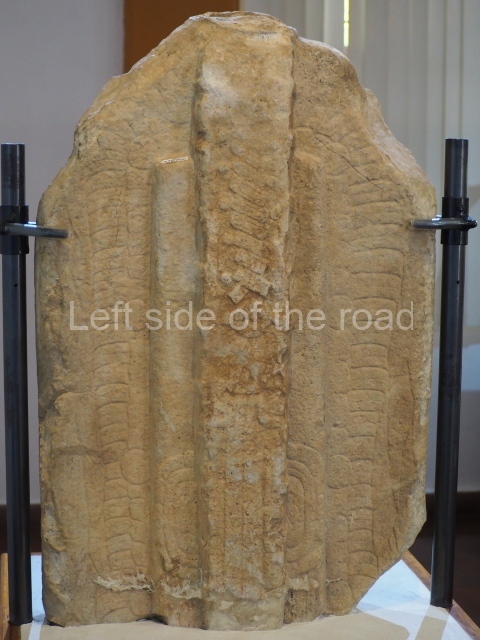

The most important architectural complex (Group C) is undoubtedly the ball court and the adjacent plaza, which boasts the largest number of carved stelae at the site. The ball court structure is made out of finely cut blocks of limestone and is abutted to a fairly high hill slope on which sits another small acropolis consisting of three low mounds around a small plaza open to the south-west; an altar stands in the middle of the plaza, while residential mounds occupy the terraces near the top of the hill. The ball court is of the enclosed variety and one end is larger than the other; this is a common characteristic in the eastern Chiapas Highlands and was thus designed to accommodate a megalithic seating area for spectators at one end of the court. A fragment from a Preclassic monument was reused in the central part of the seating area. Situated on the platform with access stairways and in front of it are several stelae; Stela 29 was reused as an altar in front of the stairway. The adjacent plaza, which is very large, is delimited by elongated platforms and there is a mound in the middle of it. Around and on top of the platform on the north side are six fairly large stelae and another four on the south side; including all the stelae and other fragments, there are approximately 20 monuments in this part of the site, of a total of 40 reliefs. In relation to the stylistic evolution of the sculptures at Chinkultic, Navarrete has this to say ‘The ball court and the plaza in front of it witnessed the simultaneous use of at least three styles: 1) no figures, only initial series; 2) thickly outlined rigid figures; and 3) figures forming scenes with richly garbed secondary dignitaries, with a greater emphasis on the quality of the carving than in filling in spaces’.

Monuments

Although the eastern Chiapas Highlands experienced a notable decline in population after the Classic era, several monuments with dates from the tenth baktun (corresponding to the Terminal Classic) have been found. Of particular note in this respect is the last Maya date recorded in the Long Count system: 10.4.0. 0.0 (AD 909), inscribed on a monument from the Amparo estate, as well as Monument 101 at Toniná. From the Sacchana estate, in the foothills of the Cuchumatanes Highlands in Guatemala, relatively close to Chinkultic, we know of the upper sections of two stelae with the dates 10.2.5.0.0 (AD 874) and 10.2.10.0. 0 (AD 879), transported to the Ethnography Museum in Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century. The Comitan Stela, reported by Blom in 1926, shows the date 10.2.5.0.0 (AD 874) and possibly comes from Tenam Puente, the regional capital at the west end of the Comitan Valley. This epigraphic evidence suggests that the Maya population in this part of the Chiapas Highlands maintained its classic religion and culture after the so-called collapse of the Maya civilisation in the central lowlands of the Peten region.

Lynneth S. Lowe

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp468-470

Getting there:

From Comitan. Take a combi heading to the Lagos/Lagunas de Montebello opposite the Centre de Arbustos on the . M$55 each way. Get off just after Km30 where the site is signposted to the left. There’s a walk of just under two kilometres, mostly flat but a little bit of an uphill climb just before reaching the site. The site is well served with gardeners and one of them would more than likely give you a lift back to the main road, M$20. Regular combis head back to Comitan

GPS:

16d 07′ 25″ N

91d 47′ 00″ W

Entrance:

Free