Uxmal – Yucatan

Location

In Yucatec Maya, the name of this site means ‘three times built’ (from ox, three, and mal, the times a task or act is repeated) or ‘place of the abundant harvests’ (from ux, to harvest). One of the most powerful and beautiful cities in the Maya area, Uxmal is situated in a fertile valley in the north-west of the Yucatan Peninsula, in the Puuc region, Yucatan state, 78 km from the city of Merida. It is reached by federal road 261. The area comprises a low mountain range, which runs for nearly 140 km barely surpassing 300 m above sea level at certain points and lends its name to the region. This is an area of small valleys with sloping land that facilitates the movement of soil; as a result, farming has always been very important. So much so that in the 16th century the region produced two harvests a year and is nowadays known as the ‘granary of the Yucatan’. The large quantity of contemporaneous sites near Uxmal is evidence of the fertility of the land since pre-Hispanic times.

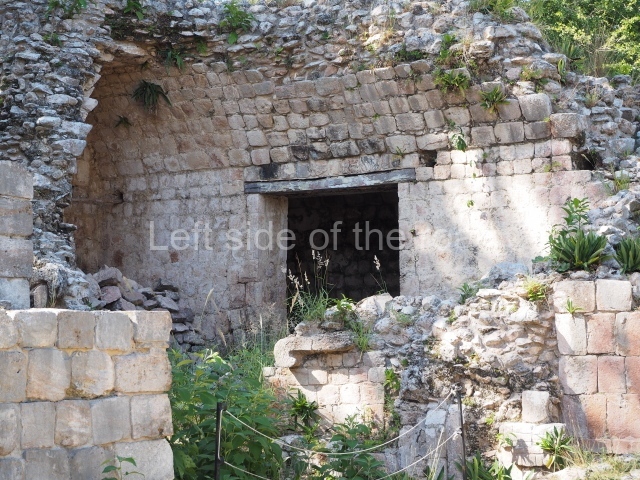

However, the area lacks surface water; due to the permeability of the soil, the rivers run underground and the Maya had to seek water in caves and then store it in two types of constructions: the natural aguadas, which they covered with several coatings, and the bottle-shaped cisterns, known in Maya as chultunes (of which there are over 100 in Uxmal), which collect water in the paved area around the mouth. During the rainy season they held considerable quantities of water, guaranteeing a continual supply.

Pre-Hispanic history

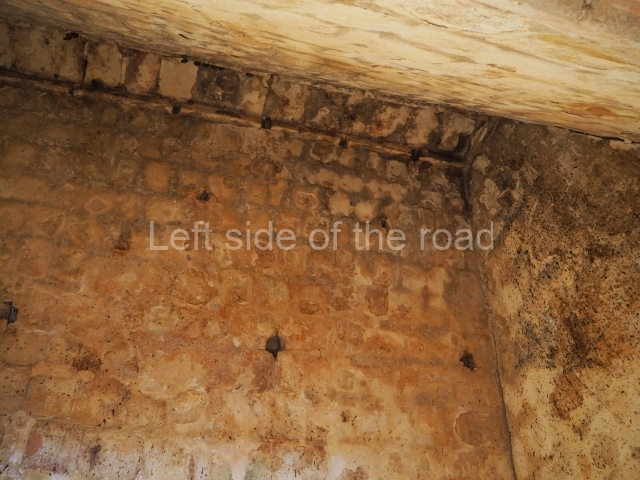

The studies conducted to date suggest that the city was very large. Between AD 800 and 1000, Uxmal had a population in excess of 20,000 and covered a surface area of approximately 12 sq km. Most of the inhabitants lived in houses, possibly made of masonry, which provided them with a roof over their heads and a bench for sleeping on. The interior spaces were dark and poorly ventilated as the only source of air and light was the opening that served as the entrance. Daily life was conducted outdoors. The women prepared food in kitchens made of perishable materials which were situated near the houses. Clothes were woven in the interior courtyard and the pottery was dried in the sun before being fired. The men also performed their tasks outdoors: they worked the hard stone tools and utensils in an area near the dwellings, and they also quartered, dried and salted animals near the home, as well as weaving ropes, baskets, nets and mats. Although most families had their own dwelling, we know that there were family groups who shared a set of houses. In other Maya sites in the Yucatan Peninsula that existed at the same time as Uxmal there is archaeological evidence of multifamily residences being occupied by over 500 people. Uxmal was a walled, cosmopolitan city where travellers and merchants came to exchange goods and ideas.

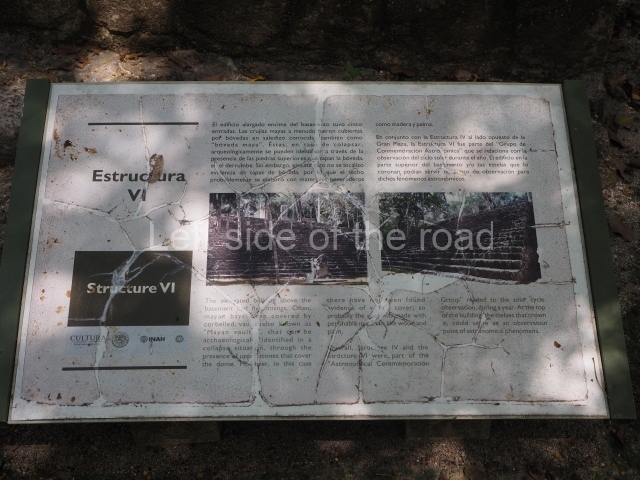

The inhabitants included priests who knew about the complex cycles of the Maya calendar and the stars, who could read and write, experts who planned, calculated and coordinated hydraulic, civic and religious works, artists who designed harmonious architectural groups, stone facades with thousands of mosaics, stelae that were adorned with the portraits of the city rulers and narrated the important events in their lives. There is much evidence of Uxmal’s relations with the other Maya and Mesoamerican cities of the day, the use of a numerical, calendric and writing system, the presence of precincts covered by a system known as the ‘corbel vault’, and the stelae that decorate the plazas and are closely related to the buildings are three elements commonly found in the great Maya sites of the classical world. Temples on top of pyramidal platforms, buildings lining ball courts, structures surmounting high platforms and the quadrangular layout of the precincts are just some of the characteristics of the great urban centres in ancient Mexico. Today, we can still see examples of decorative sculpture from the powerful Teotihuacan, in its day the largest city in Latin America. The sophistication and opulence of the ancient Maya are evident in the extraordinary architecture at Uxmal, serving as an age-old testimony of the city’s former glory. The political, religious and administrative part of Uxmal that we know today occupies a surface area of barely 1 km from north to south and 600 m from east to west. It contains a dozen consolidated buildings which are nowadays open to the public, having gained UNESCO World Heritage status in 1996.

Site description

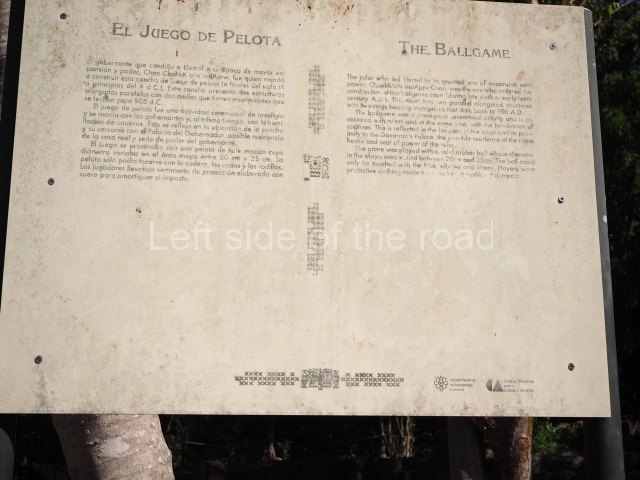

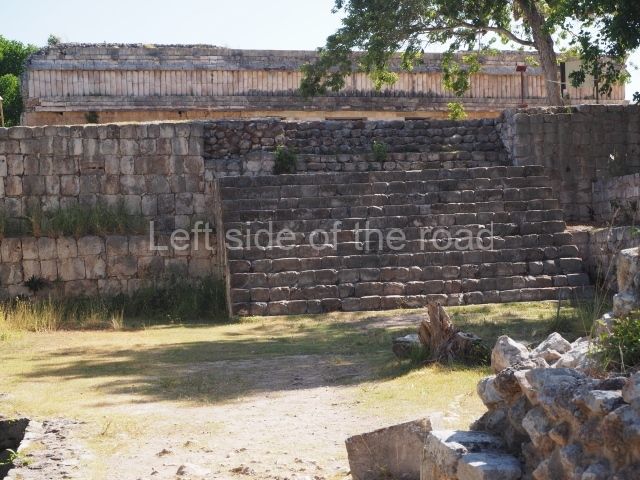

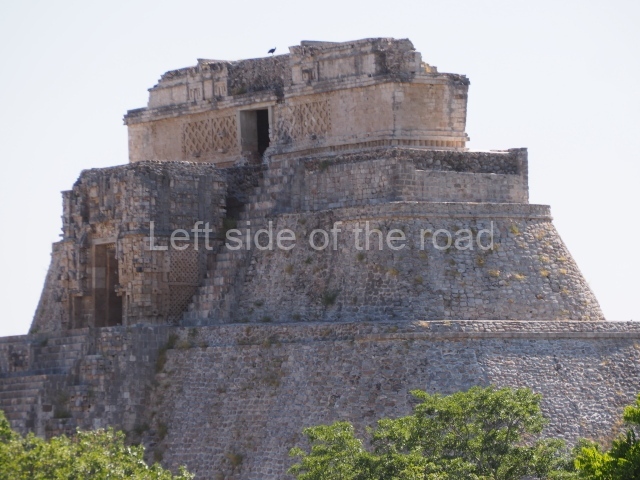

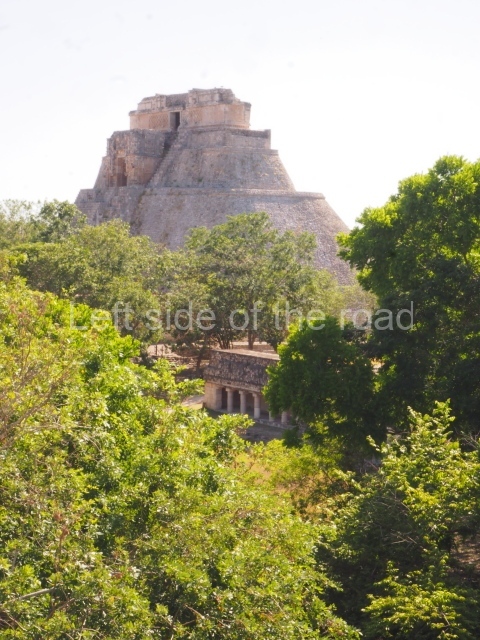

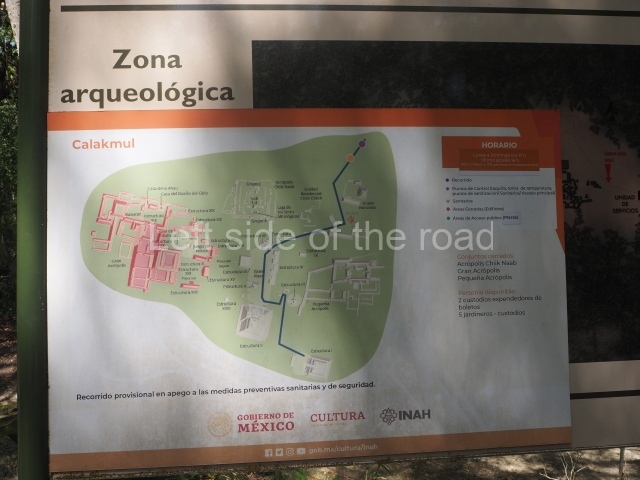

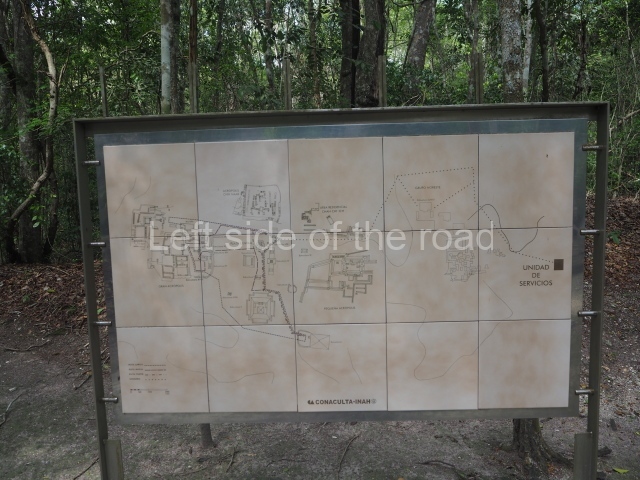

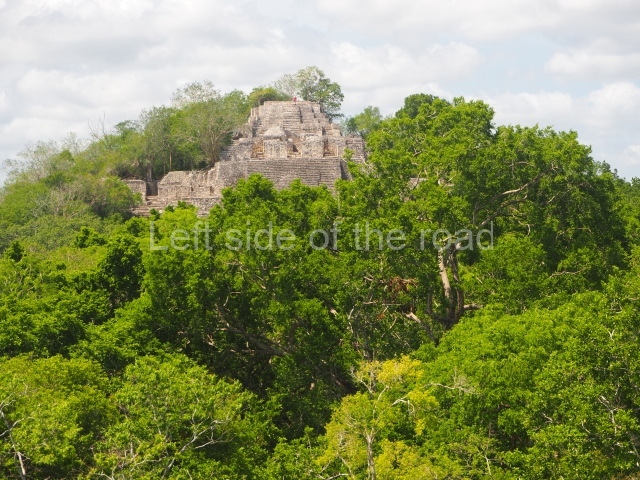

In the mid-17th century a Franciscan historian, Diego Lopez de Cogolludo, described Uxmal in his Historia de Yucatan and assigned European-style religious or civic functions to certain buildings. For example, the Governor’s Palace and the Nunnery Quadrangle are names that are totally alien to the Maya world and the men who built them, but nowadays they are widely known as such. Other names are derived from the oral tradition that the English traveller John L. Stephens picked up from the Maya inhabitants in the area at the beginning of the 19th century: the Pyramid of the Magician and House of the Old Woman are names that appear in the legend of the dwarf of Uxmal and have been identified as such for over a century by the people who live near Uxmal. Time and vegetation have gradually hidden Uxmal. Few buildings are still standing and await the patient, meticulous work of archaeologists. If one were to make a visual tour of the ancient city from the highest point at the site, it would begin at the Pyramid of the Magician and then continue west to the large courtyard known as the Nunnery quadrangle. Visible to the south is the Ball court and a platform surmounted by two structures: the House of the turtles and the Governor’s palace. A group of buildings only partially visible lies to south-west: The Great pyramid and the House of the pigeons. The North Group, North Building, Cemetery and West Building, as well as the House of the old woman in the south-east, all resemble mounds. The general orientation of the principal buildings is north-north-west and according to the archaeo-astronomical studies undertaken there are significant visual relations between them, as well as with neighbouring sites.

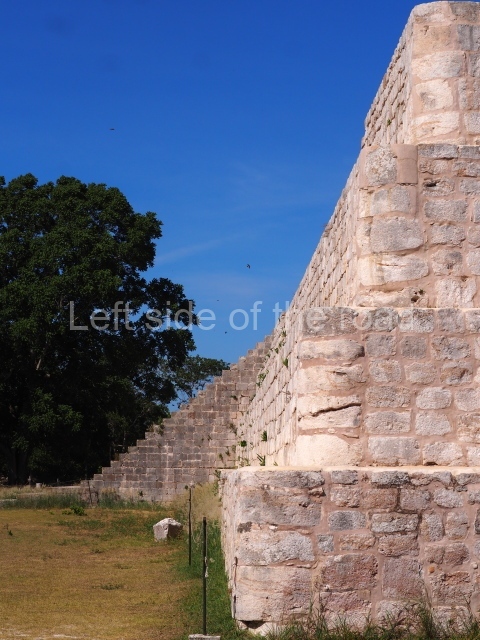

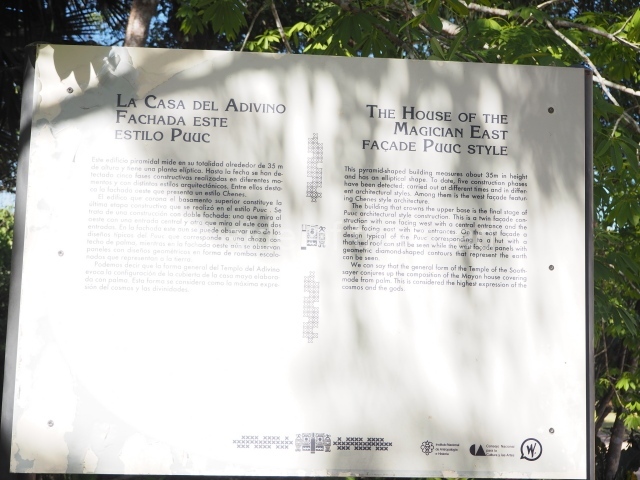

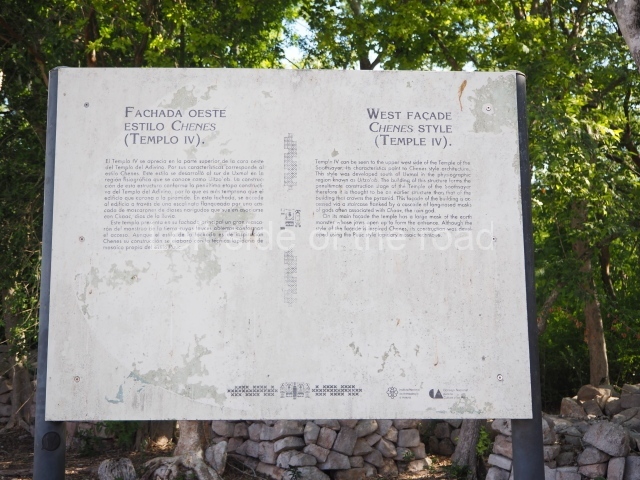

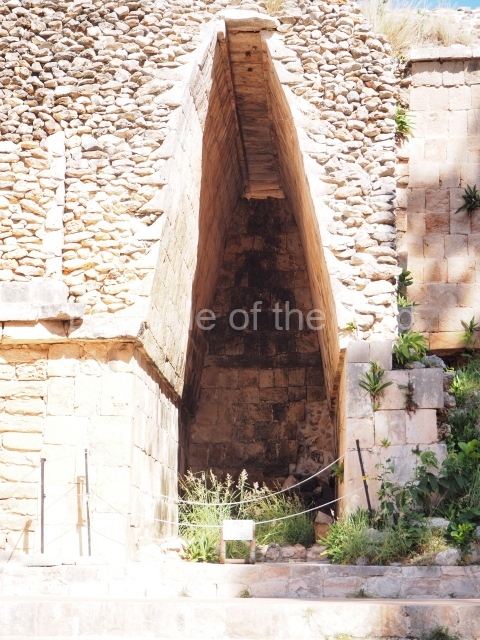

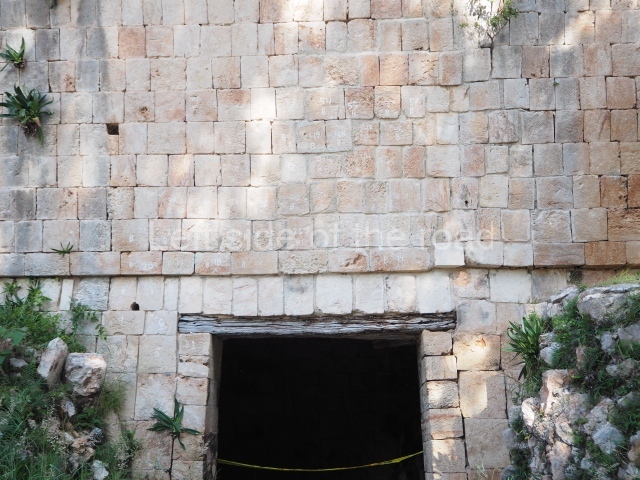

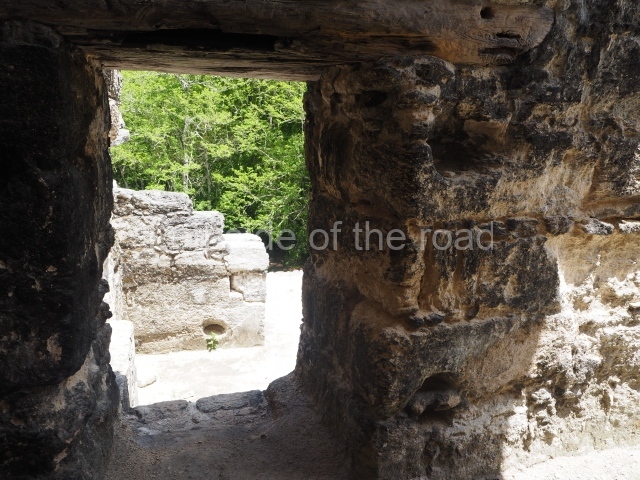

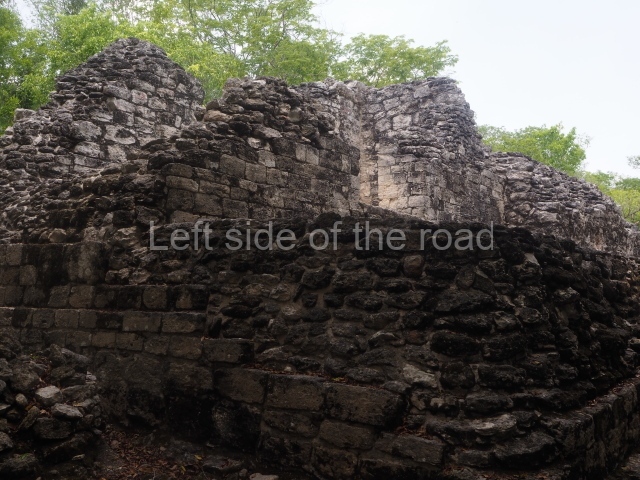

At Uxmal, as in other parts of ancient Mexico, the public architecture is defined by large open spaces delimited by constructions in which the interior area is virtually non-existent; this is an architecture of exterior spaces, in which the population would gather for periodic activities and ceremonies. The ancient architects at Uxmal skilfully combined the needs of the people with the technical devices developed by their ancestors centuries earlier: they covered large bays with Maya vaults and constructed handsome buildings designed to be observed from the outside. For example, at its base the Pyramid of the Magician measures 70×50 m; it stands approximately 27 m high and is surmounted by a temple which can be accessed by either the east or west stairway; meanwhile, the interior space, which consists of a single 20×3 m bay, is divided into three 6.5×3 m chambers. In this structure, which contains at least five construction phases, the main facade faces west and the stairway, flanked by stacks of masks placed at an angle of 45°, leads to a temple whose interior barely measures 4×4 m and consists of two rooms.

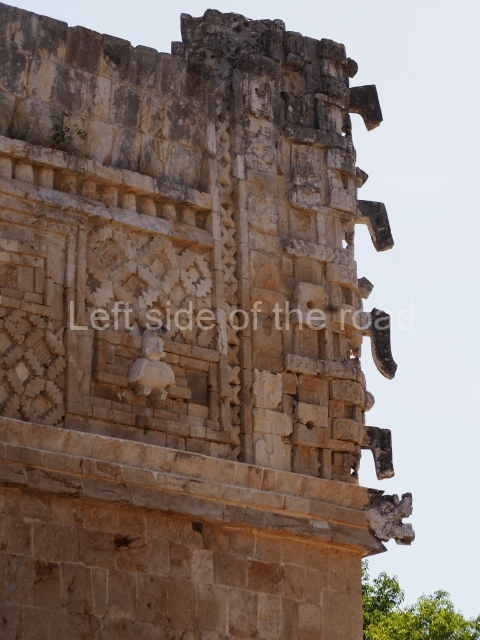

Prayers to the celestial gods

Although each precinct has its own appearance and their functions vary, they are all decorated with masks of a long-nosed Maya deity, probably Chaac, the rain god. Although this theory has traditionally been accepted, in recent years there have been suggestions that the masks might also represent the powerful lord of the sky. Based on different sources of information, we can now confirm that the gods Itzamna and Chaac share a series of similar elements in their representations and certain functions within the Maya pantheon. The masks at Uxmal have round eyes with blazing eyebrows that recall those of serpents, open mouths revealing curved, possibly feline teeth, and a large curved nose, possibly derived from the tapir (not from the elephant as this species does not exist in Latin America), which adopt varying positions. The masks are complemented by ear ornaments that recall those that were worn by the great Maya lords. At Uxmal the frieze decoration makes reference to the sky (the latticework), to the power that comes from the sky (the two-headed serpents), to fertility and to rain (the masks) and to lightning (the stepped frets). Combined in different ways on different buildings, these elements constitute ongoing praise for the Maya divinities of the heavens, as well as elegant ornamentation for the facades.

A powerful dynasty

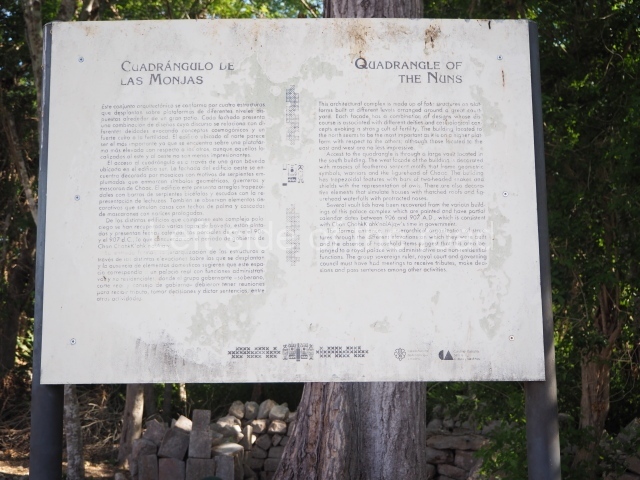

Although the history of the various Maya cities can be gleaned through the hieroglyphic inscriptions on stelae, altars, lintels, stairways, carved bones, ceramics and other artefacts, at Uxmal there are just two stelae and other painted texts from the Nunnery Quadrangle that have enabled us to identify the two governors who gave the city part of the appearance we see today: the lords Chac Uinal Kan and Lady Bone, parents of the powerful Lord Chac, who commissioned the construction of the Nunnery Quadrangle and the Governor’s Palace, jewels of Maya architecture.

An image of the Maya world

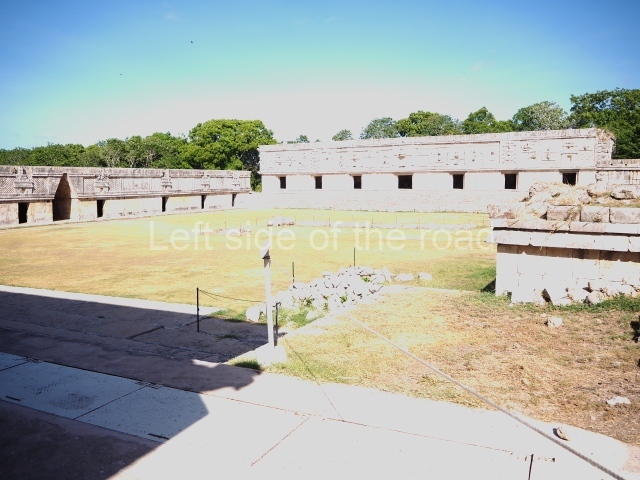

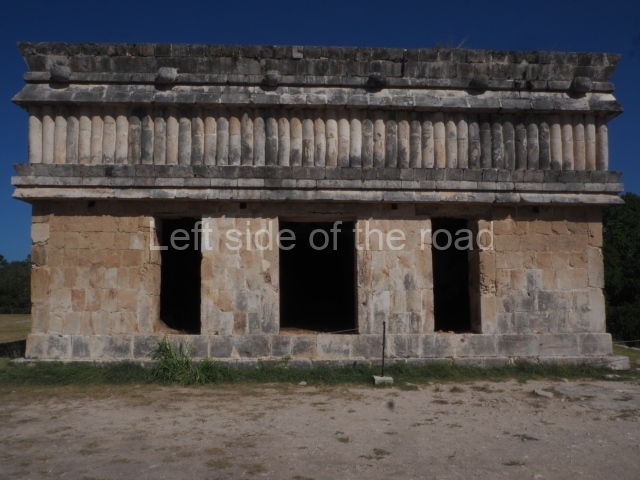

One of the characteristics of the architecture of this city is the elongated structures with bays arranged in quadrangles accessed via a monumental arch. The best preserved is the Nunnery Quadrangle: a plaza in the shape of an irregular quadrilateral delimited on all four sides by buildings with double facades, interior and exterior. The central courtyard measures 45×65 m and is surrounded by four benches, each at a different height, from which the buildings rise. These are identified by the name of the direction in which they are situated: South Building, East Building, North Building and West Building. Stairways of varying heights link the plaza to the buildings; this elaborate design is evidence of the complex rituals that were performed there. When these structures are viewed from the south of the city, it is nearly possible to see all four main facades thanks to the unique orientation of each building. It is as if the ancient Maya architects had taken into account not only functional, ritual, symbolic and aesthetic functions, but also the view the observer in the plaza would have, from either the arch or entrance, or from the platform further south that stands nearly 20 m high. They clearly attempted to give prominence to the North Building, not only because of its decoration but also its unique features and situation some 7 m above the level of the courtyard. Its harmonious façade with its extraordinary combination of planes and voids, bare walls and decorated friezes, is one of the most exquisite in Maya art. It has 11 quadrangular doorways whose frames contrast with the thickness of the wall, producing a sensation of lightness and interplays of light and shadow at different times of the day. The frieze is decorated with latticework, frets, Maya huts and stacks of masks that surpass the level of the roof, producing a complex culmination of volumes and spaces. Recent studies suggest that this complex symbolically represents the quadrangular conception of the Maya world, in which each side is associated with a cardinal point and has different meanings. If this interpretation is correct, the Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal was developed as a miniature image of the cosmos and must have been used for a variety of rituals.

A masterly design

Of all the buildings in the Mesoamerican world, perhaps the most beautiful and most harmonious in terms of its proportions, a crowning achievement of Maya architecture, is the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal. Situated on a three-tiered artificial platform, it is an elongated construction comprising three buildings: one in the middle and two at the sides, connected by small recessed volumes that permitted access from one to the other. These passageways, subsequently walled up, are possibly the highest corbel vaults known (over 6 m high) and being slightly convex lend overall elegance and harmony, as well as continuity with the three main architectural constructions. The facade displays the same decorative characteristics as other buildings at Uxmal, skilfully combining bare walls, decorated friezes and openings. The frieze is decorated with frets and masks of the sky deity (who appears here with the Maya sign for ‘star’), which are harmoniously distributed on a panel of stone mosaic latticework. Sculpted above the central opening are eight two-headed serpents which form an inverted triangle; above this, seated on a horseshoe throne, is the now incomplete figure of the great Lord Chac, the governor of Uxmal. The lintels that sealed the openings were made of wood and thanks to the description of an English traveller from the first half of the 19th century we know that they were very beautiful. They may well have represented the members of the city’s ruling dynasty.

The abandoned city

Uxmal was abandoned by the Maya in the 11th century, and it was only then that other major cities such as Chichén Itzá and Mayapan acquired a prominent place in the life of the Yucatan Peninsula. However, both the Maya chronicles from the colonial period, known as the Books of Chilam Balam, and the texts of the Spanish conquerors contain numerous mentions of Uxmal. Later on, in the 19th century, tireless travellers ‘discovered’ it for the western world, visiting it, describing it, painting it and photographing it. In the 20th century it was studied by Mayanists from different disciplines: archaeologists, epigraphers, archaeo-astronomers and art historians. Thousands of visitors from all over the world come to Uxmal every year, so although the ancient city was abandoned nearly a thousand years ago, thanks to its former power and magnificence its glory lives on today.

Laura Elena Sotelo Santos

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp356-363.

- Pyramid of the Magician; 2. Nunnery Quadrangle; 3. Ball Court; 4. House of the Turtles; 5. Govenor’s Palace; 6. Great Pyramid; 7. South Temple; 8. House of Pigeons; 9. House of the Old Woman; 10. West Group; 11. Cemetery Group; 12. Colomns Group; 13. Terrace of the Monuments; 14. North-west Group; 15. North Group.

Further Information:

Getting there:

Uxmal is located alongside the road that joins Hopelchén and Muna, also passing the major site of Kabah. Regular buses run along this route but the timings can be crucial if you wish to visit the two sites on the same day. There is a written timetable displayed in the Sur ‘bus station’ in Hopelchén. It takes about an hour for the bus (which starts in Merida) to arrive in Muna.

GPS:

20d 21′ 54″ N

89d 46′ 30″ W

Entrance:

M$90