The Albanian Cultural Revolution

Art as a means of promoting Socialism in Albania

Included here are links to various exhibitions that will, hopefully, provide an idea of the unique characteristics of Albanian Socialist Realist art and especially the monumental sculptures known as lapidars. The paintings and small sculptures that were on display in the Tirana National Art gallery. According to the most recent information I have available it is still ‘closed for renovation’ and was supposed to have re-opened in 2023 but there’s no sign of that yet. Whenever it does re-open whether it will have on permanent display those works of art which are attached to some of the posts listed will be, I fear, unlikely.

As for the lapidars the majority of them have been either left to decay or have been the subject of official or ‘unofficial’ vandalism. How long they will last will be totally dependent upon how attached to them the local populace might be.

All those countries that achieved a socialist revolution – and were led by parties that followed the Marxist-Leninist ideology (and for me there are only really four; the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania (PSRA) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV)) – realised the importance of art as a propaganda tool to promote socialist ideals and to counter the propaganda of capitalism. Each country produced that art with their own national characteristics and that produced in Albania was particularly unique and extensive, covering many aspects of the plastic arts.

Socialist Realist Art in Albania

When I first visited Albania in November 2011 I hadn’t been there too long before I realised a number of things about the monuments that had been constructed during the socialist period (1944-1990). The first was that there were a lot of them – at that time I didn’t realise just how many. Secondly, that some of them were quite remarkable, and unique, examples of Socialist Realist Art and, thirdly, they were all in danger, whether it be through ignorance, simple neglect or vandalism – be it ‘official’ (as an expression of political hatred, as has already happened in a number of cases, such as the Five Heroes of Vig in Shkoder and more recently The Four Heroines in Mirdita) or ‘unofficial’ – some people destroy because they are themselves unable to create.

1971 National Exhibition of Figurative Arts – Tirana

This article was first published in New Albania, No 6, 1971. It discusses the general idea of art in a socialist society, how the Albanians saw ‘Socialist Realism’ with mention of a handful of works (out of 180) that were displayed at the National Exhibition of Figurative Arts in Tirana in the autumn of 1971.

A Reflection of the Progress of our Figurative Arts

This article first appeared in New Albania, No 6, 1976. The bi-annual Figurative Arts Competition and Exhibition seemed to have been postponed from 1975 and instead took place in 1976 to coincide with the 35th Anniversary of the Founding of the Party of Labour of Albania.

The ‘Archive’ Exhibition at the Tirana Art Gallery

This exhibition (that took place during the latter part of 2021) at the National Art Gallery in Tirana seemed to include virtually everything that had been in storage over the last 30 years. But calling it an exhibition was a bit of a misnomer. The word exhibition gives the impression that a bit of thought and consideration had been put into the mounting and display of a collection of art. That is supposed to be the art of a curator – although that was totally neglected in this case with all items placed in the room with consideration of context. This included works of art that had been damaged for whatever reason in the past.

The Albanian Lapidar Survey (ALS)

This was the most comprehensive survey ever carried out which documented as many as possible of the lapidars (monuments) that were still in existence at the time of the survey in March 2014. The survey recorded the physical state of the monuments (some badly damaged and neglected) and added any other pertinent information available – such as artists involved, date of inauguration, exact location using GPS technology, etc. – as well as creating an extensive photographic record of their condition at the time.

Following the survey three volumes were published, both in physical form as well as a downloadable pdf. Volume 1 contains a number of articles introducing the concept of the lapidars and their role within Albanian Socialist society. These articles appear in both Albanian and English. This volume also contains the information of the 659 lapidars that were recorded at the time. (A number of others have since been added.)

Volume 2 includes one or two photos of each lapidar in the northern part of the country, Volume 3 in the southern part – the dividing line being set at N40º42’38”.

There are links to descriptions and photos of the lapidars as well as information of the sculptors and architects involved in this vast artistic project.

The lapidars here are listed in the order they appeared in the list of the ALS.

ALS 1 – Monument to the Partisan

Located in central Tirana, commemorating the liberation of the city on 17th November 1944, the work of the sculptor Andrea Mano. The first of the sculptural lapidars, being installed in 1949.

ALS 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 The more ‘humble’ Albanian lapidars

As is described in Evolution of lapidars in Albania – part of the struggle of ideas along the road to Socialism the concept had a very humble beginning, often the simple marking of a grave of a fallen Partisan/s and as time, and prosperity, developed the grave taking on a focal point to celebrate important dates and the lapidar being made more elaborate over time. This story of the lapidars is shown in the short film ‘Lapidari’.

ALS 5 – Vojo Kushi, Sadik Stavaleci and Xhorxhi Martini

The representation of the last military action of Vojo Kushi, Sadik Stavaleci and Xhorxhi Martini in Albanian Socialist realism is an interesting one as it has been depicted in a number of formats so offers a (possibly) unique opportunity to compare how the event has been presented to the Albanian people, history and posterity. Although the sacrifice of the three is commemorated it is Vojo Kushi who is in the forefront of these representations, his last action of storming an Italian tank being an act of bravery that has transcended even the counter-revolution of the 1990s.

ALS 8 and 12 – National Martyrs’ Cemetery – Tirana

The National Martyrs’ Cemetery, Tirana, is the most important monument to those who fell in the struggle against Italian and German Fascism between 1939 and 1944. It’s also the location of one of the largest examples of Socialist Realist sculpture in the country – Mother Albania.

ALS 9 – Monument to the young people’s anti-fascist group Debatik

Located in Tirana Park, not far from the post-Socialist monuments that celebrate the German Fascist dead as well as those of the British imperialists.

A statue of a young male Partisan and a vilklage woman who is providing him with refreshment. It is the work of the sculptor Hektor Dule and is located in Tirana Park.

ALS 13 – Monument to the Artillery – Sauk

Although the plan is to attempt to record all the monuments from the socialist period in Albania’s history there are, and will be, occasions when I will have arrived too late. Either the ‘democrats’ (a mixture of monarchists and neo-fascists) have got there first and destroyed the works of Socialist Realist art as it represents all that they despise and fear – such as any of the statues of Enver Hoxha – or those lumpen elements who see only scrap value in a piece of metal – that has led to the damage to the statue of the Five Heroes of Vig in the northern city of Shkodër. Destruction and vandalism has been the fate of the Monument to the Artillery in the hills to the south of Tirana, close to the town of Sauk.

ALS 17 – Monument to Heroic Peze

Looking like a cross between a pistol and a huge road sign, the Monument to Heroic Peze sits at the junction to the village of Peze, along the old road between Tirana and Durres. This huge block of concrete, in its imagery and words, tells the story of the important role that this small village played in the war against fascist occupation (both Italian and German), the formation of the National Liberation Front and the concept of People’s Power.

ALS 19 – Monument to the 22nd Brigade – Peze

The Conference of Peze, which took place in September 1942, was only possible as the Peze Çeta (Partisan Guerrilla Group) was so feared by the fascist invaders that they could provide a safe environment to enable the discussions on the formation of a National Liberation Front to take place. This was in a location only 20 kilometres from the capital of Albania, Tirana. As the war developed the organisational structure of the People’s Army changed and became more organised. After final liberation the efforts of these men and women started to be recognised throughout the country and hence the Monument to the 22nd ‘Shock’ Brigade.

The third major monument in the Peze Conference Memorial Park is the cemetery to those from Peze who fell during the anti-Fascist war of Independence. The Peze War Memorial is a short distance from the main area of the park and you could be excused for not knowing it’s there.

ALS 21 – Peze Conference Memorial Park

The Peze Conference on 16th September 1942 was important in establishing the organisational structure for the forthcoming struggle for liberation against the Fascist invaders, first the Italian and then, when Italy fell to the Allies, the Germans. This important meeting took place in the home of Myslym Peza who had a large house and land on the edge of the small village of Peze, about 20 kilometres south-west from Tirana and this is now the location of the Peze Memorial Park.

ALS 25 – Elbasan Martyrs’ Cemetery

All the major towns in Albania will have a Martyrs’ Cemetery and the one for Elbasan is towards the east of the town centre. When it was constructed it probably would have been very much in the countryside, the built-up area around it now seems to be relatively recent, within the the last 20 years or so.

ALS 27 – Monument to the 15th Partisan Assault Brigade – Elbasan

I must admit I have a little bit of a difficulty in working out exactly what the shape of this monument is supposed to represent. It’s like a huge belt or a ribbon.

ALS 34 and 34 – Librazhd Martyrs’ Cemetery

Like many of its kind in Albania the Librazhd Martyrs’ Cemetery sits on a high location over the town. This is both to give due reverence to those who gave their lives in the National Liberation War as well as to reflect that the war itself was very much one that was won and (for the Fascists) lost in the mountains.

ALS 38 and 39 – Qukës-Pishkash Star

There are some of the lapidars in Albania that can truly be called monumental in all meanings of the word. One of these is the massive and impressive Arch of Drashovice and another is the Qukës-Pishkash Star, to the side of the road from Librazhd to Përrenjas, just opposite one of the impressive viaducts of the, now, sadly neglected Albanian railway system. The sheer scale of the star can be appreciated when you look at the picture above which includes the team who catalogued the Albanian lapidars in the summer of 2014.

ALS 49 – Pogradec Martys’ Cemetery

A statue of three Partisans, two men and a woman, who stand shoulder to shoulder in front of the recently re-opened Martyrs’ Museum.

ALS 98 and 100 – Monument to the First School and a Martyrs’ Lapidar – Proger

As is the case in many towns and villages in the UK (and also in Western Europe) where it’s common to come across a war memorial (originally for the war of 1914-18/9, the ‘War to end all wars’ but which became only Part 1) this is also the case in Albania. At the time of the National Liberation War from 1939-44 the population of the country was a little more than a million and so it’s no surprise that the ‘Martyrs’ (as they are known in Albania) came from even the smallest places. Progër is no different in that case. What makes the village different is the substantial lapidar commemorating the First Communist Party Cells. This small village, off the main road, also has a Monument to the First School and a Martyrs’ Lapidar.

ALS 99 – Proger – First Party Cell of the PKSH

The majority of the lapidars throughout Albania celebrate the events of the National War of Liberation and those who fought and died in that struggle. Others celebrate and commemorate events in the period of the construction of Socialism but there are few (probably a surprise to many) that are specifically devoted to the Communist Party of Albania (later the Party of Labour of Albania). One such – I only know of one other and that’s on the facade of the museum in Ersekë – is to the First Party Cell of the PKSH in the small village of Progër, close to Billisht and Korçë, not far from the border with Greece in the south-east of the country.

ALS 141 – Monument to Communist Guerrillas – Korça

This lapidar consists of a bronze statue, half body, starting just below the waist, around about twice life size. The statue stands on a plinth, which is about one and half metres high. This plinth and statue are part of a general structure, the background of which is a huge, stylised flag – the dimensions of the backdrop are (very roughly) 4 metres high, 3 metres wide and ¾ metre deep. All the stonework will have a base of concrete and is faced with slabs of white-ish marble.

ALS 121 – Martyrs’ Cemetery, Korçë

Many of the martyrs’ cemeteries in Albania are situated on hills above the towns and villages and this is certainly the case with the Martyrs’ Cemetery, Korçë, where the highest point is a fair hike from the centre of the town below. However, it’s worth the effort as, on a clear day, you have a fine view of the town, the fertile valley below and the mountains to the west as well as a fine example of Socialist Realist Art.

ALS 166 – Resistance – Monument to the struggle against Fascist invasion in Durres

Being the main port of invasion by the Italian Fascists on 7th April 1939 it’s not a surprise that in commemoration of that event, and especially the resistance that was shown by a significant proportion of the population (but not the self-proclaimed ‘King’ Zog who ran away as soon as the Italian ships came into sight) that there are a few monuments to this, constructed in the Socialist period. One is to the individual sacrifice of Mujo Ulqinaku (that used to stand close by the Venetian tower at the bottom end of town) and the other is to the general principle of ‘Resistance’ in Durrës, which is located right next to the waterfront and very likely one of the places the Italian fascists would have landed.

ALS 167 – Mujo Ulqinaku – Durrës

The first shots in Albania’s National Liberation War (although it wasn’t called that at the time) were fired on 7th April 1939 when the Italian Fascist forces invaded the port city of Durrës (as well as other locations along the coast). For years the country, ruled by the self-proclaimed ‘King’ Zog I (even before he was dead he was planning a dynasty!) had been a puppet state of the Italian Fascists and when the invasion did take place no official structure was in existence to defy the invaders. It was therefore left to brave individuals, such as Mujo Ulqinaku, to take up the banner of resistance. His sacrifice is commemorated by a monument close to the coast where the invasion took place.

The overwhelming number of Socialist Realist monuments in Albania are constructed from either concrete or bronze. However, there are occasional variations from this norm and there are a few mosaics (though not on the massive scale of ‘The Albanians’ on the National History Museum in Tirana) including those in Bestrove, Llogara National Park and at the Durrës War Memorial.

ALS 194 – Lushnjë Martyrs’ Cemetery

Many of the Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout Albania have a statue of one or more Partisans to stress that those commemorated were those who died in the National Liberation War of 1939-44. Sometimes there’s just one male Partisan, as in Korcë or Ersekë, sometimes there will be both a male and a female, as in Librazhd, sometimes (though rarely) there’s a group of three, as in Pogradec but there are also times when the symbol of sacrifice is in the form of a single female, as in Saranda and Fier. There’s a certain commonality between many of these statues, having been constructed at a similar time, but the statue of the female Partisan at the Lushnjë Martyrs’ Cemetery is quite unique in style and presentation.

ALS 244 – Shoket – Comrades – Permet

Shoket – Comrades – was one of the early sculptures to be placed in the Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout Albania, a simple monolith (lapidar) being the most common form of monument. It is the work of Odhise Paskali and was inaugurated in 1964, the same time as the monument to the Permet Congress was unveiled in the main square of the town.

ALS 263 – Partisan and Child, Borove

The statue of a Partisan and Child, just beside the main road passing through the small village of Borove in the south-east of the country, is one of the most charming of Albanian monuments but its charm obscures a much darker story. That story is less obvious now than it was in 1968 when it was created, in a different location and part of a bigger tableau.

ALS 301 – Seventh Assault Brigade, Sqepur

Time hasn’t been too kind to the lapidar to the Seventh Assault Brigade which is situated beside the main road between Fier and Berat in an place called Sqepur. It’s at the top of a hill and is relatively exposed to the elements and this has taken it’s toll on the plaster work.

ALS 306, 307, 308 and 309 – Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery

Many of the Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout Albania are situated on hills, sometimes quite high hills, in the vicinity of the cities and towns. This is the case with the Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery which, when it was constructed, would have been clearly seen from the centre of the town, the area around Sheshi Pavarësia (Independence Square) and the Bashkia (Town Hall). Up to the 1990s the buildings weren’t that tall but subsequent construction of high-rise flats has meant that you don’t really see the cemetery until you’re almost upon it.

ALS 361 – Monument to Communists murdered by Italian Fascists – Tepelene

Apart from what it commemorates, that is the torture and murder of four communists from the from the area by the Italian Fascists in 1943, the lapidar – just below the castle walls on the main road between Gjirokaster and then heading north towards Tirana – isn’t exceptional and doesn’t have any real architectural value, but it encompasses a number of aspects which make it slightly unique.

ALS 376, 392 and 393 – Martyrs’ Cemetery, Gjirokaster

There are a lot of mountains in Albania and they played a role in the success of the Communist led Partisan çeta (guerrilla groups) in defeating first Italian and then German Fascism. For that reason most of the Martyrs’ Cemeteries in Albania tend to be high above towns, in the surrounding hills, as is the case in Tirana. On my first visit to Gjirokaster I was, therefore, scanning the hills above the old town looking for the tell-tale signs of a white lapidar indicating the location of the cemetery.

Gjirokaster Martyrs’ Cemetery and the 75th Anniversary of Liberation

Independence Day – 29th November 2021 – in Gjirokaster

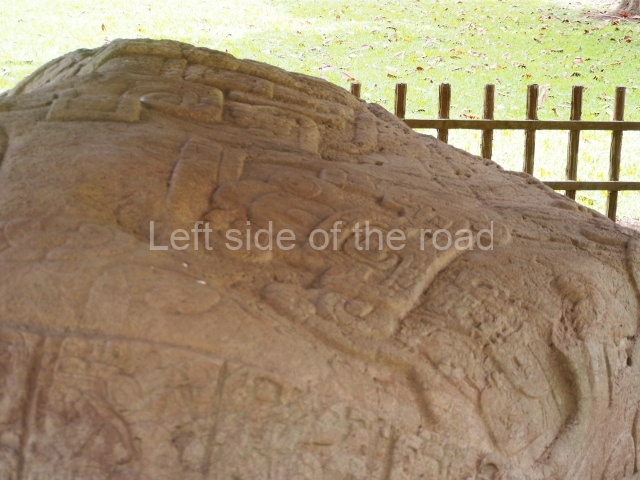

ALS 394 – ‘Skenderbeu’s Wars’ bas-relief in Gjirokaster

Many of the lapidars in different parts of Albania have suffered from vandalism and neglect. This is sad as it is displays a lack of respect of the Albanians for their heritage. Those with a particular Socialist message have suffered the most, attacked by the monarcho-fascists when the country was going through a period of anarchy in the late 1990s. Caught up in this denial of the past are also some of the monuments dedicated to the country’s ancient ‘national hero’, Skenderbreu, and a bas-relief called ‘Skenderbeu’s Wars’ the ‘stone city’ of Gjirokaster has likewise being ignored and allowed to fall into decline.

ALS 395 – Education Monument – Gjirokastra

There’s a unique lapidar in Gjirokaster, in southern Albania, which was erected to commemorate the struggle for education in the Albanian language when the country was occupied by the Ottoman Empire. This monument to education is an obelisk in the shape of a stylised scroll, or a certificate rolled up, upon which are carved images depicting the struggles of the past as well as the intentions for the future. Its official name is ‘Obelisku kushtuar pionierëve të arsimit shqip’ (‘Obelisk dedicated to the pioneers of education in [the] Albanian [language]’.)

The problem of the origin of the Albanian People and their language

This article was first published in New Albania, No 4, 1977. It addresses the somewhat complex issue of the origin of the Albanian people and the roots of the Albanian language – a language very different from all others in the surrounding area. It is included here to give some background to the obelisk to this topic in Gjirokastra, ALS 395 above.

ALS 398 – Partisan Memorial – Gjirokastra

Most of the monuments in Albania are not complex works of sculpture. Many are simple columns, with inscriptions, some of those being quite small. These are known as ‘Lapidars’ in Albania. (‘Lapidar’ doesn’t have a direct translation into English although ‘monolith’ is a possibility – and might even have a German root.) In between the monumental and the columns are stand alone statues and structures and the Partisan Memorial – Gjirokastra, is one of those.

ALS 414 – Saranda War Memorial, Albania

Through its monuments and memorials you can tell a lot about a country, its history, its heroes, its respect for itself, the class relationships, the political balance of power, even the state of the economy.

ALS 416 – Five Fallen Stars Rise Again – Dema Monument

The monument at Dema (Manastir), just outside of Saranda in southern Albania, to those who died in the war of liberation against Fascism returns to something close to its original condition.

ALS 424 – Sarandë’s Martyrs’ Cemetery

A number of Martyrs’ Cemeteries have a single female partisan as the principal statue, Fier and Lushnje are two that immediately come to mind. This was also chosen as the case in Sarandë’s Martyrs’ Cemetery.

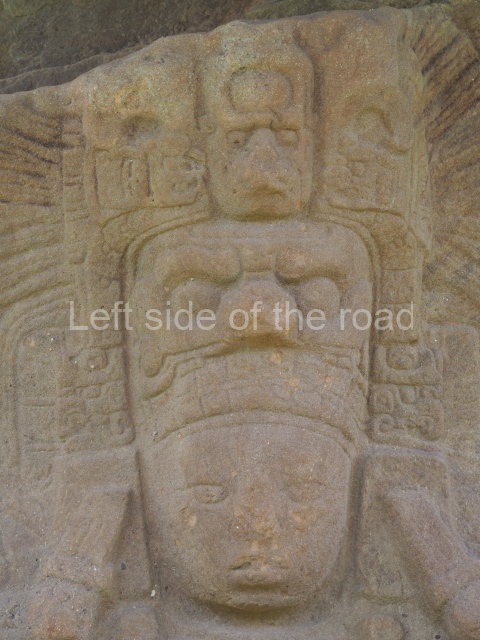

ALS 438 – Arch of Drashovice – Introduction and Statue

A journey along the valley of the Shushicë River is interesting under any circumstances, the road is rough in places (most places) but the view of the mountains and the countryside is astounding and makes the effort worth it. When you add the Arch of Drashovice 1920-1943 it’s almost an obligation.

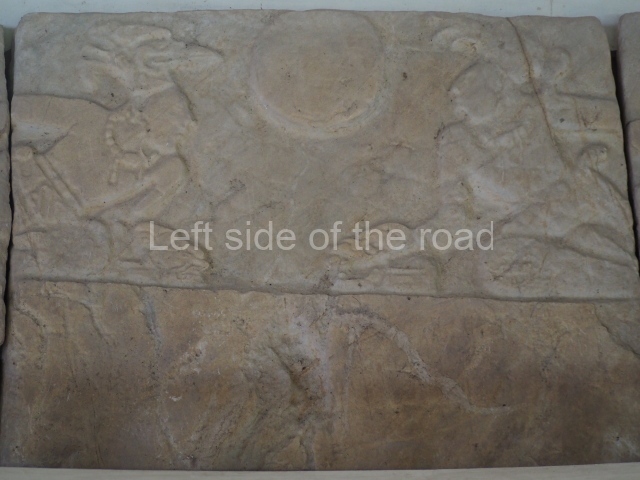

ALS 438 – Arch of Drashovice 1920

The magnificent Arch of Drashovice is such an amazing structure with so much to tell us that I’m breaking the description up into three parts. This is the second and addresses the images relating to the battle in 1920 against the Italian invaders, a battle (and war) fought by an irregular army of peasants, workers and intellectuals against a heavily armed imperialist force.

ALS 438 – Arch of Drashovice 1943

If victory was only temporary in 1920 (due to the betrayal by the despot and usurper ‘King’ Zog) the success in 1943 led to a situation where, really for the first time in Albania, the people had the opportunity to build a life and a country for themselves, by themselves. With the expulsion of the Nazis at the end of November 1944 the country gained true independence and it was then for the people to take their own destiny into their hands. No longer could they put the blame on others. The battles that took place in September and October 1943, and which are depicted on the Arch of Drashovice, played a major role in that final victory.

Mosaics play a small part in the history of Albanian lapidars but when they do appear they do so in an impressive and memorable manner. Although not strictly a lapidar the most impressive is the huge the ‘Albanian’ mosaic on the façade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana. Also interesting and worth a visit is the mosaic in the Martyrs’ Cemetery of Durrës. Each of these have their distinctive aspects and the mosaic, near the village of Bestrovë close to Vlorë, is another unique monument in its own right.

ALS 504 – Mushqete Monument – Berzhite

In the last days of the fight for the National Liberation of Albania by the Communist led Partisan army a crucial battle took place along the road from Elbasan to Tirana, south-east of the capital. To commemorate this battle the Mushqete Monument was erected at Berzhite.

What does this monument stand for? The Mushqeta Monument

This article first appeared in New Albania, No 4, 1976. It is reproduced here to give more information about this crucial battle against Hitlerite Fascism in the final days of the National Liberation War – and only a matter of days before the liberation of Tirana and the effective end of hostilities in Albania.

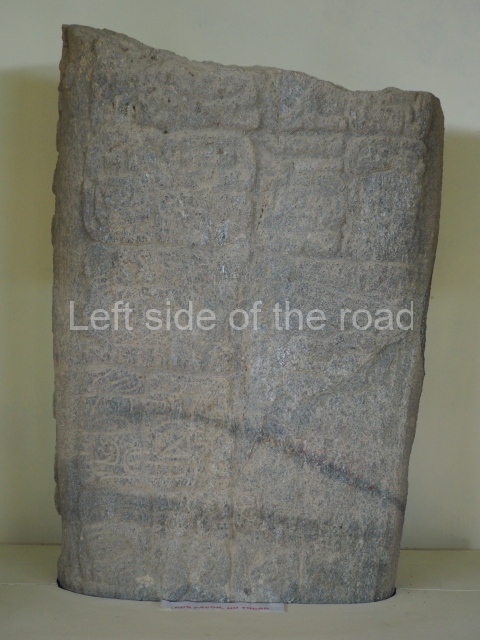

ALS 675 – Bas Relief and Statue at Bajram Curri Museum

The early Albanian lapidars were relatively simple affairs, uncomplicated memorials to those who had died in the National Liberation War against Fascism and for Socialism. Come the Albanian ‘Cultural Revolution’ – starting in the late 1960s – the intention was to use such monuments in a much more educational manner as well as establishing a distinctive Albanian identity. This meant that artists who had been educated and trained under the Socialist regime were encouraged to depict events and memorials in a much more figurative manner. Examples of this approach are seen in the Musqheta monument in Berzhite and in the Peze War Memorial. As the Cultural Revolution moved into the 1980s a new approach developed. This was one where the monument told a story which had developed over time, showing a continuum of the struggle. This is seen, in a truly monumental manner on the Drashovice Arch (close to Vlora) and in the Albanians Mosaic on the façade of the National History Museum in Tirana but also on the more modest, at least in size, bas-relief and statue in the north-eastern town of Bajam Curri – although it also presents some new questions of the meaning of Socialist art.

ALS 675 – Five Heroes of Vig – Skhodër

Celebrating solidarity and the willingness towards self-sacrifice in the common cause the statue of the Five Heroes of Vig once stood in one of the central squares of Skhodër, in northern Albania. After a period ‘out in the wilderness’ – close to the city rubbish dump and subject to crass, petty thievery it has now found a new permanent home in the centre of a roundabout to the north of the city.

As time went by that search for, and recording of, the Albanian lapidars grew into a more general search and recording of other artistic works in the public domain. This included mosaics, bas-reliefs and group statues. On top of that were the works of art in the (few) remaining museums and art galleries.