Summary execution of a petroleuse – note the vicious bourgeoisie on the left

More on the ‘Revolutionary Year’

28th May 1871 – the end of ‘Bloody Week’ of the Paris Commune

On the 18th March 1871, the Parisian working class gave a lesson to the international proletariat that it was possible for the oppressed and exploited of the world to take the future into their own hands. On the 28th May, the last day of slaughter of those very revolutionaries, coming only 71 days after that momentous spring day of hope, through their martyrdom, they taught the working class of the world that the audacity of challenging the power of the ruling class came with a price. For the 28th May 1871 marked the end of ‘Bloody Week’, the end of the Paris Commune.

The Paris Commune of 1871 started when a group of washer-women thwarted a pre-dawn raid by the capitulationist and pusillanimous government forces who sought to rob the people of the artillery they had paid for in their attempts to prevent the fall of their city to the invading Prussians. What began as a self-defence action in the hills of Montemartre soon spread throughout the city and by the afternoon of March 18th barricades were being constructed and the revolution had begun.

18th March – Avenue Jean-Jaures

In the post on the anniversary of the start of the Commune I listed what I consider to be some of the achievements of that, literally, world-changing event. For it was both in their achievements and failures of the Communards that later revolutionaries were to learn so much and which determined the manner in which they pursued the revolutions in their own countries, especially in Russia, Albania and China.

In studying revolutions there are both positive and negative lessons that need to be learnt. Failure to do so will lead to the same mistakes being made resulting in similar consequences. As the conditions in which a revolution takes place are always specific to the times and the conditions in a particular country it is inevitable that new mistakes will be made. That’s not a problem.

As Chairman Mao stated a revolution is not a dinner party (Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, FLP, Peking, p8). Revolutions are uncontrollable, it becomes almost a living organism which has a mind of its own. An organised revolutionary party might be able, at times, to direct the flow of events but they are no more than desperate men and women trying to control a river in spate. Dig the channels in the right place at the right time and the water can be controlled. Make one slight mistake and the water will break the banks and all bets are off – until the next crucial moment is reached. If a revolution can be controlled it is not a revolution. This makes the achievements of the Communists in Russia, Albania and China all the more remarkable.

Before going on to the mistakes made by the Communards it’s worthwhile re-iterating some of the achievements in that short two and a bit months. In the first few days:

- rents for dwellings abolished

- articles that had been pawned declared not for sale

- the wage differentials between men and women were abolished

- officials would not get any more than a ‘working-man’s wages’

- the church was separated from the state

- church property was to be national property

- religious iconography was to be removed from schools

- the guillotine to be publicly burnt, as a symbol of the old regime

- night work for bakers was abolished

- planned the reopening of factories closed by owners and these to be run on a collective basis

Although many of these were in response to the grievances of the Parisian working class after decades of living under a corrupt system, added to which were the hardships as a consequence of a more than four-month siege of the city – during a hard winter – by the Prussian army many of those decrees would have resonance in Britain (and most other countries throughout the world) even now.

Housing is still a problem – highlighted in Britain by the Grenfell fire of 2016; wage differentials and the ‘gender pay gap’ have long been contentious issues (however, paying everyone the same, more or less, is an easier solution to crashing through ‘glass ceilings’ and has more rationale to it than paying over-paid women as much as even more over-paid men and would have a direct impact upon the poorest in our society who, nowadays, don’t even get the crumbs that fall from the table of the rich); recent events in the Republic of Ireland demonstrates how society can be distorted when the Church has a hand in controlling civil society – not to mention the role of religion in various parts of the world and the death and destruction that comes with it; general working conditions have become worse not better in the last couple of decades in most countries even though the Gross Domestic Product might be rising – the poor ALWAYS get proportionately less in such circumstances; employment is an issue which capitalism finds so difficult to deal with it’s not even considered of any importance in the political debate; and elected representatives of the Commune could be replaced at any time if they failed to live up to their promises – so no chance of the development of a so-called ‘Political Class’, a group of self-selected, self-serving, over-important opportunists who have gained control in too many countries.

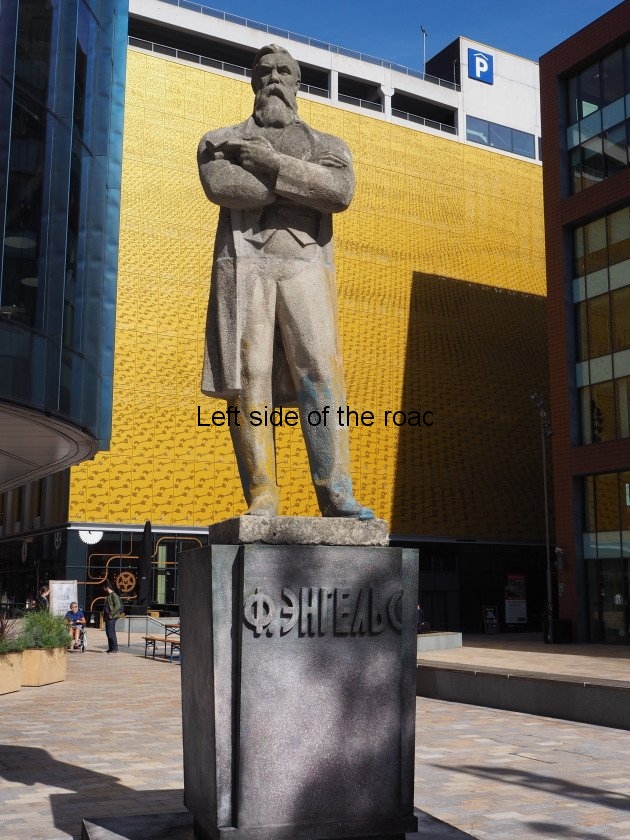

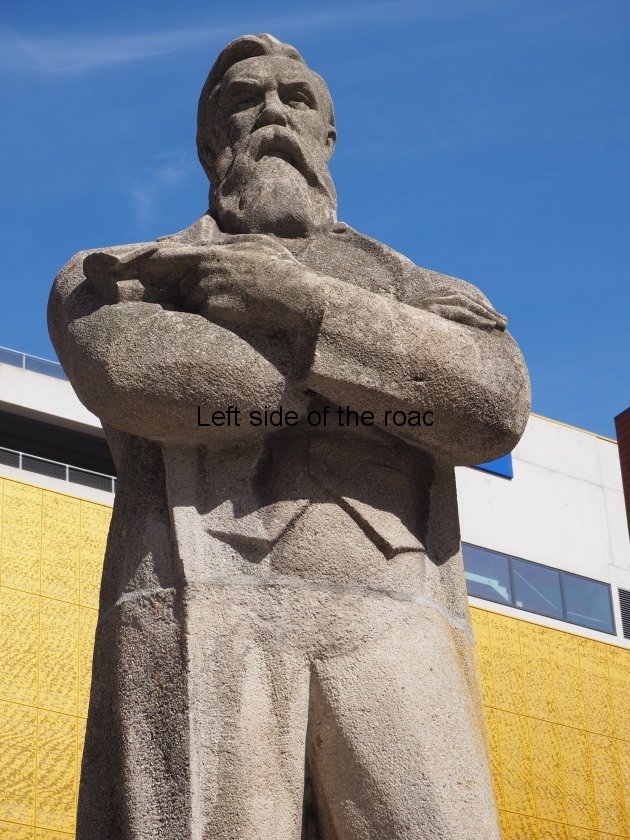

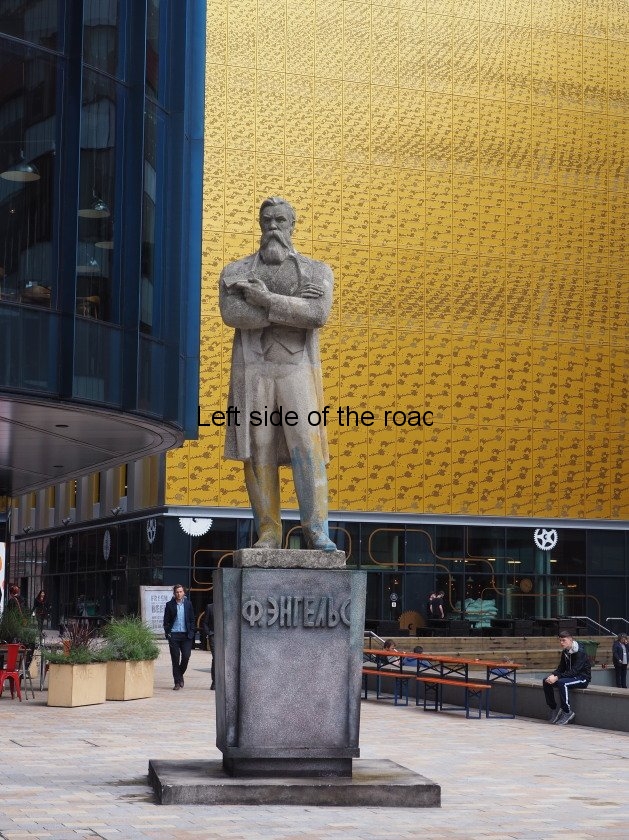

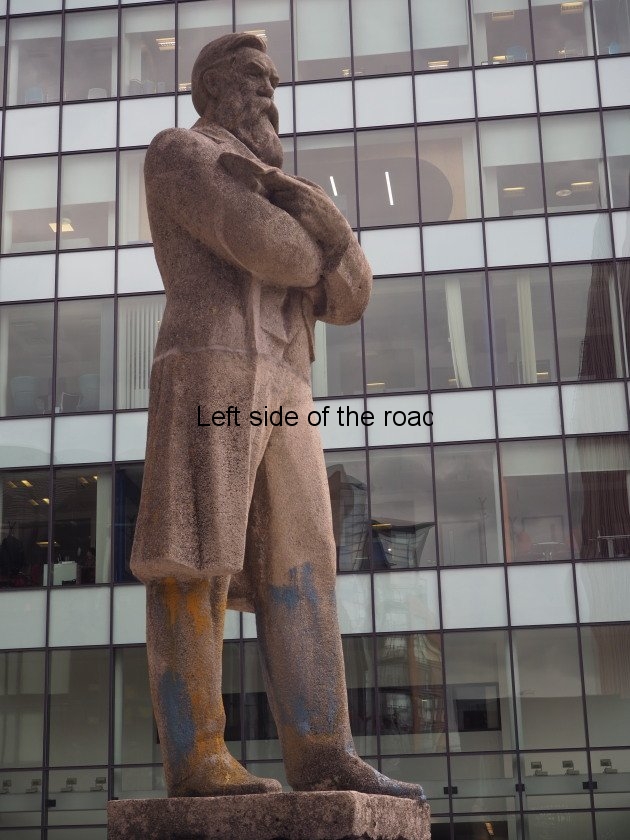

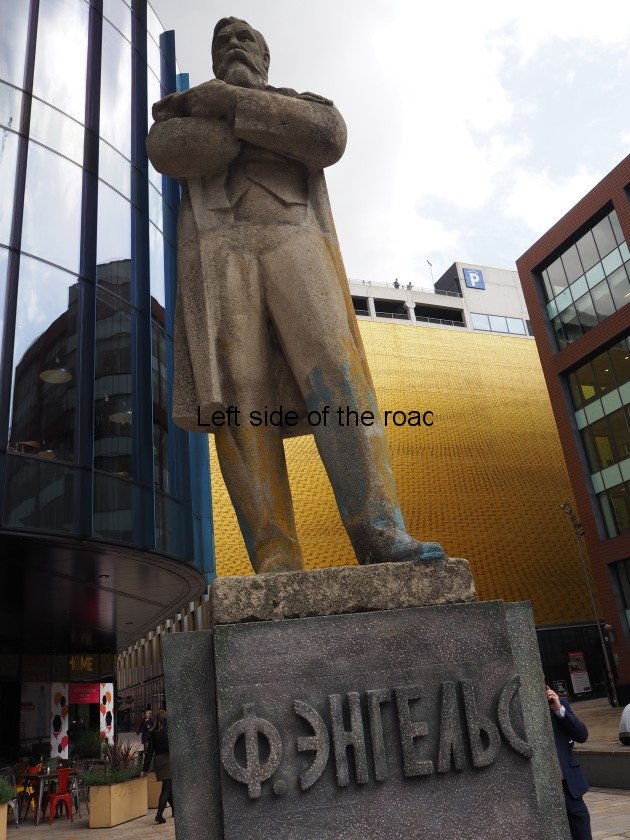

The representative structure was for the working class and it was run by the working class. At the same time it’s important to make clear that the Commune was not a state of all the people. The bourgeoisie had run society for years and had failed – a bit like now – so the Parisian working class decided that it was time for a new class to be in control and purposely excluded certain sections of society. This was the first time in history where the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ was in action – something which Marx, Engels and, later, Lenin picked up and developed in their post 1871 theoretical writings and which Lenin sought to put into practice after the Great October Proletarian Revolution of 1917.

Did the proposals and declarations of the Commune always work out as it was intended? No. Did they get some things wrong and follow an incorrect direction on some policies? Yes. But give them a break, many hadn’t had much formal education and it takes time for people to learn to do things in a new way – they weren’t given that time. Did opportunists and renegades from the working class get into positions of power which they then abused? Yes. These parasites exist in all societies and it will take decades of a new society before we can say that they definitely have been eliminated. Seventy one days was not long enough. Were they divided when unity was necessary? Yes. But that’s how things go. Either honestly or dishonestly people in such circumstances come to different conclusions over crucial matters. Here, again, time would have allowed the Commune to overcome (at least in part) some of these differences. But time there wasn’t.

But what is important is that they tried. They did not surrender when the going got tough – which happened very soon after the heady days of the recovery of the guns from the government troops. Many persisted, tried to make a difference to their community and many of them died for their tenacity and determination.

‘The sacred revolt of the poor, the exploited and the oppressed’

Not only were working men involved in running society in a new way so were women – who also established women only debating clubs which used to meet in expropriated churches and which was a revival of a practice from the bourgeois French Revolution of 1789. They took up arms and enrolled in the National Guard and also played a major role in attempting to delay the entrance into the city of the murderous Versailles troops during ‘Bloody Week’. They were never ‘victims’ (as too many women claim today). They asked for nothing – they demanded and took.

But mistakes were made which led directly to the events of ‘Bloody Week’ from the 21st-28th May 1871.

Probably the most serious was that the Parisian Communards were too magnanimous – they didn’t recognise the viper they had in the nest, the government supporters and the bourgeoisie in general who would do any and everything to see the destruction of the new workers power. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the great Russian Marxist and Revolutionary, took this particular lesson of the Paris Commune on board and his seminal work on proletarian revolution, The State and Revolution, FLP, Peking, 1970, takes as its starting point the experience of the Parisians workers.

It’s strange that this soft approach towards the enemy within persisted throughout the period of the Commune. In the Declaration of the Commune, dated 29th March 1871, reference was made to the fact that if the people of the Commune didn’t deal severely with their enemies then they would become powerful enough to destroy the revolution or, at least, be able to undermine its advances. But little was done practically to avoid the counter-revolution.

However, in all revolutionary circumstances there will be those who call for leniency towards the deposed ruling class, either out of opportunism – in an effort to protect their own class interests under the guise of being revolutionary – or, more usually, out of naivete as many don’t realise what challenging power entails and that the deposed ruling class will never accept their loss of power and will wreak vengeance on all those that try. The naïve were to learn their lesson – but when it was too late to do anything about it.

Lax security meant that bourgeois counter-revolutionaries were able to allow the entry of the government, Versailles, forces inside the walls of the city on May 21st. Once inside the forces of reaction, composed mainly of ignorant and easily manipulated peasants, just carried out a blood-lust campaign of slaughter. One of the failings of the Commune was seen in the very instrument of their destruction – the workers of Paris had failed to communicate to the vast majority of the population of France the true importance of what they were trying to achieve in the capital. The interests of the peasants were with the workers but the reaction was able to convince these soldiers that they should stick with the theocratic, capitalist state.

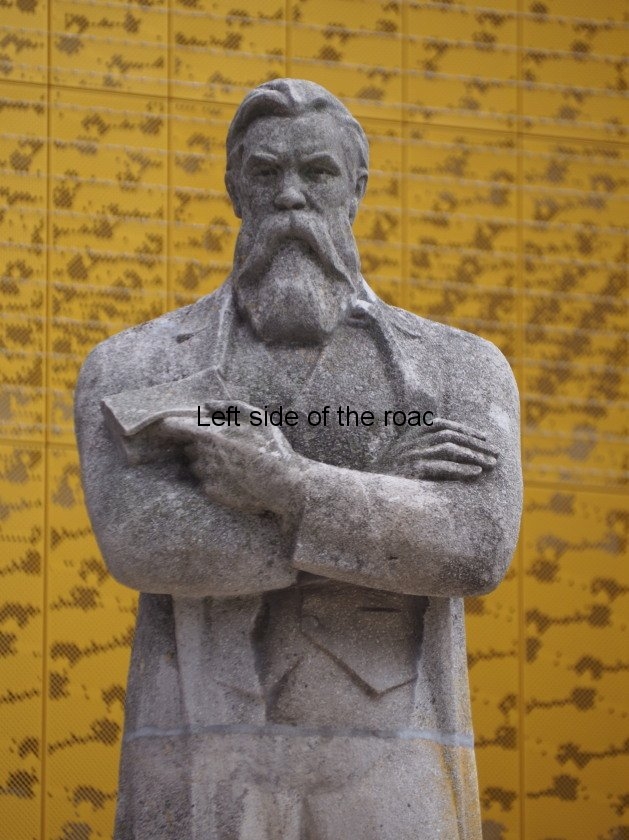

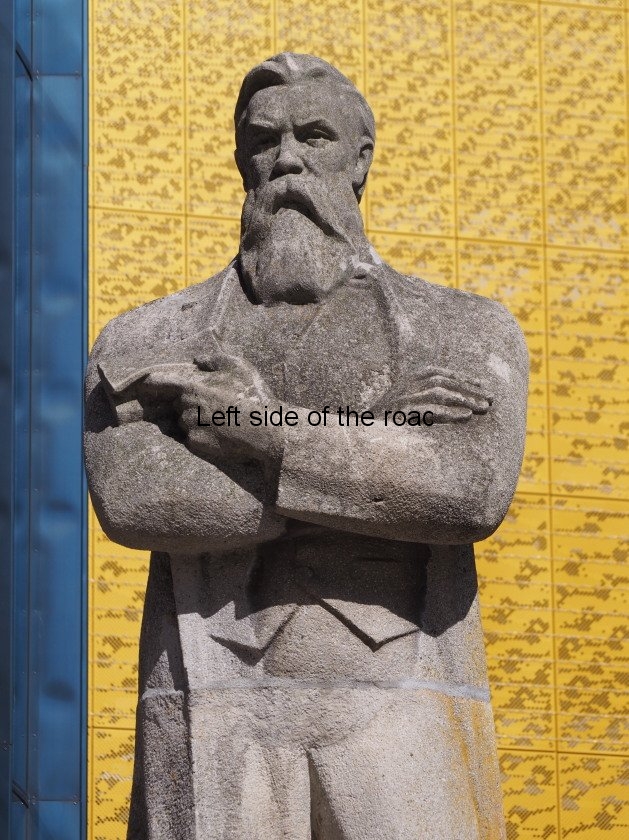

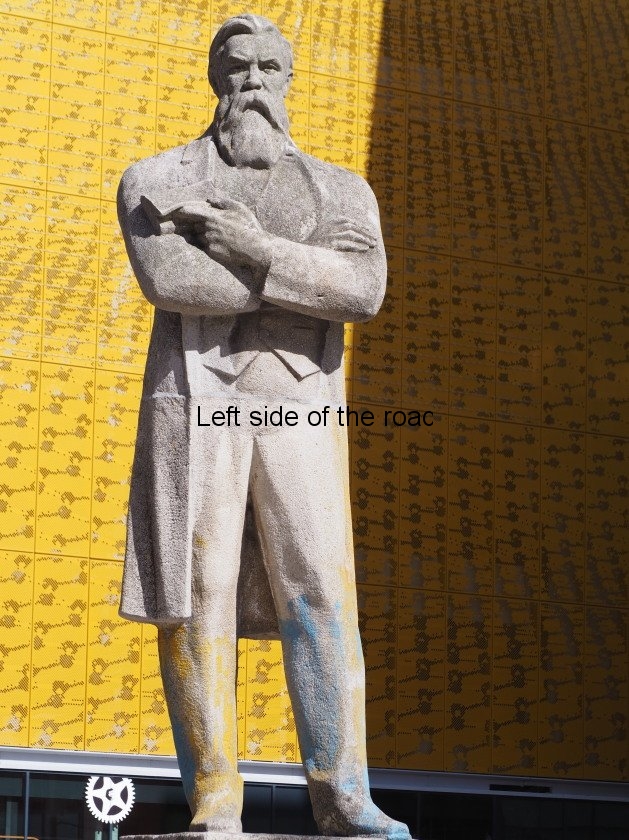

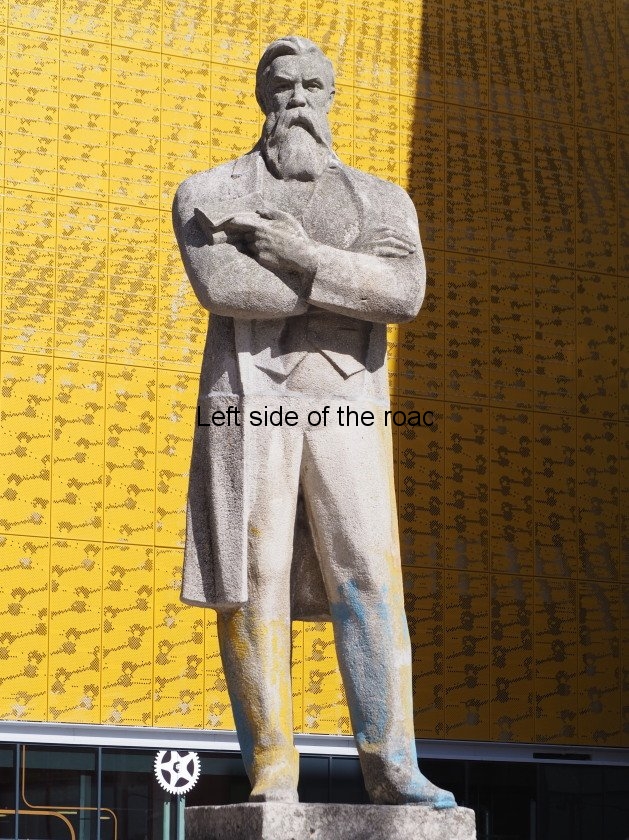

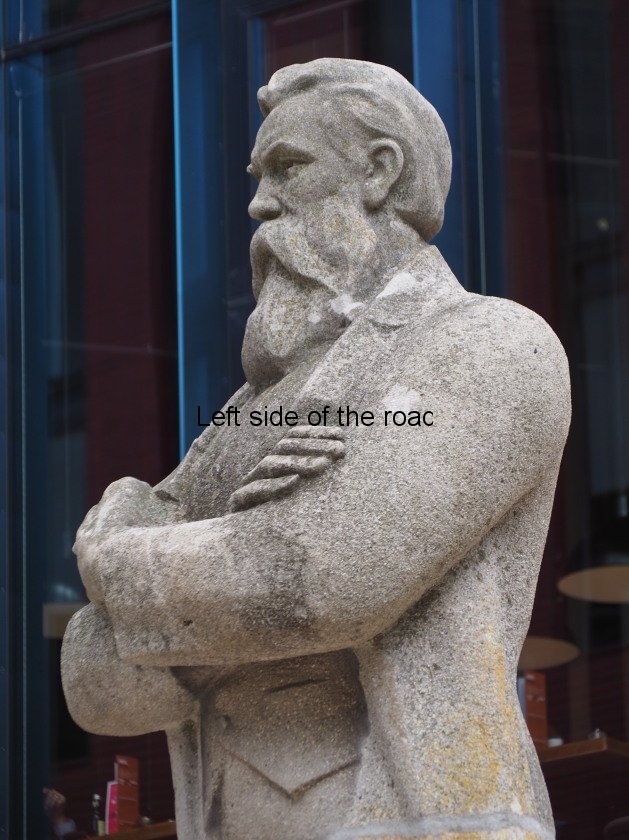

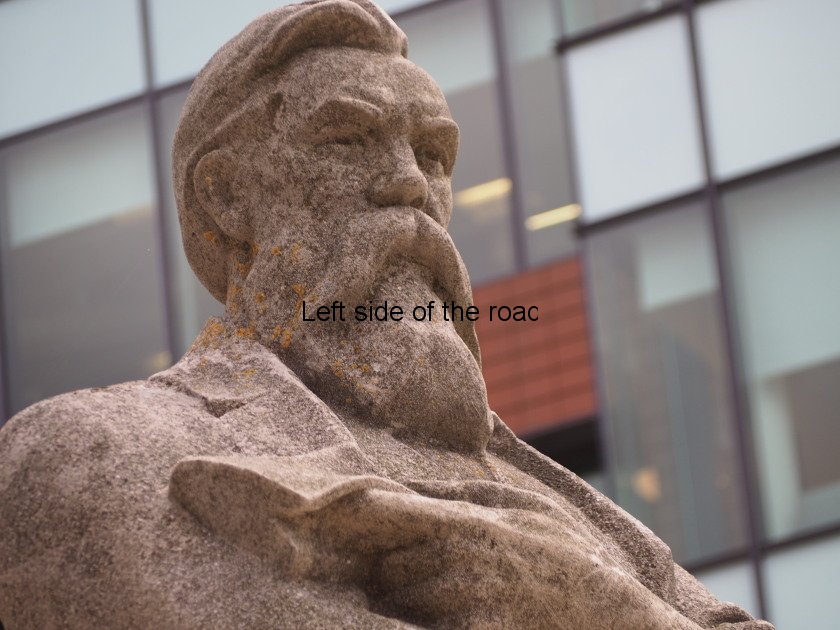

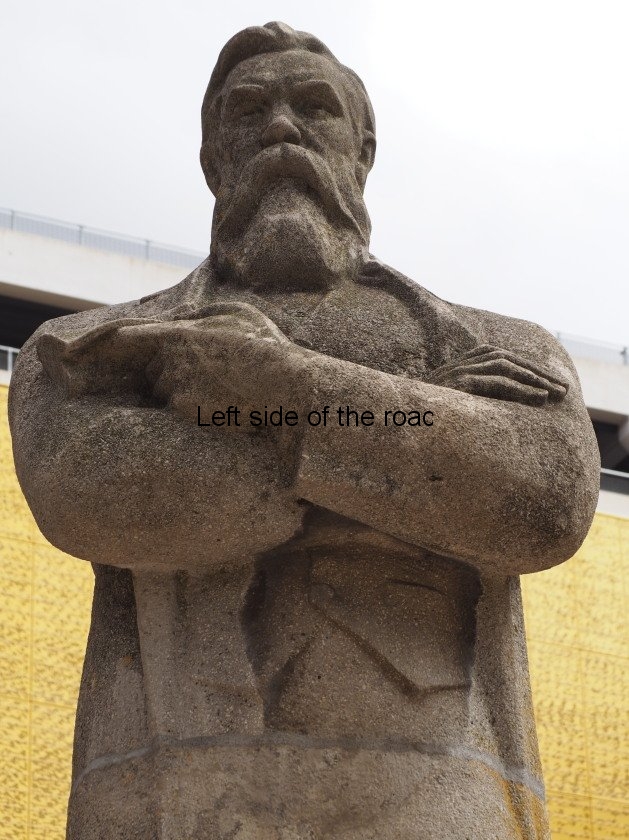

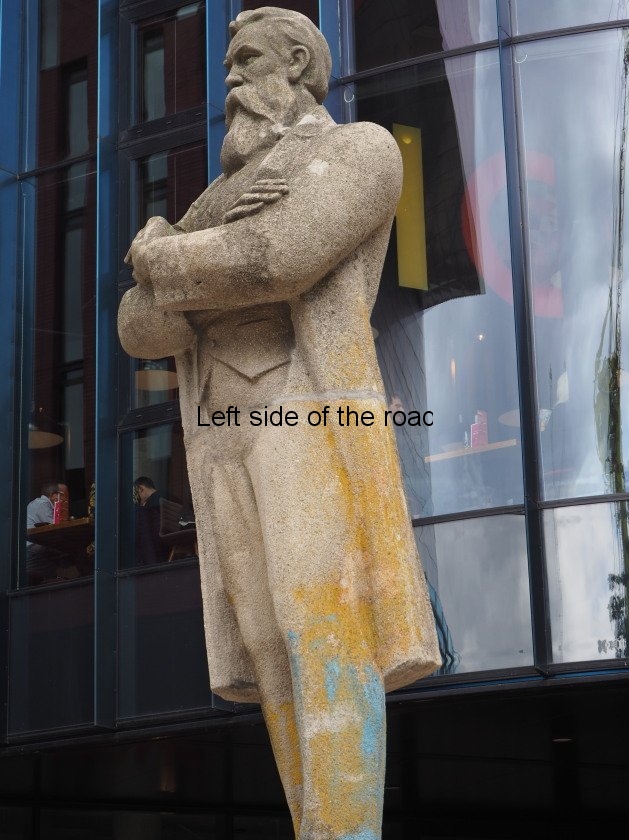

Once the defences had been breached the Commune was reduced to fighting a rear-guard action. It was soon evident that with the actions of the government troops there was literally nothing to be lost in fighting to the death. No quarter was being given so none was asked. Many of those who surrendered were subject to summary execution – the vicious and degenerate bourgeoisie egging on the executioners. History often mentions the women knitting on the occasion of the execution of the aristocrats during the bourgeois French Revolution of the late 18th century but there is little mention the finely dressed bourgeois harridans who cackled and spat as young men, women and even children, were stood against a wall and shot.

Execution of a trumpeter

The workers did fight and most notable, and for the bourgeois reaction the most notorious, were Les Petroleuses, the women who set fire to buildings in the city centre to slow down the advance of the murderous government forces. In this action there was also an idea of ‘if we can’t have these properties then neither shall you’. This was branded as mindless destruction by bourgeois commentators and the press.

The writer Emile Zola condemned the Communards for what he saw as pointless destruction of a beautiful city. He changed his mind slightly on learning of the scale of slaughter in subsequent days but at the same time his attitude that property was sacrosanct pervaded the ideas of many opponents of the activity of Les Petroleuses. Such an attitude exists to this day and can be seen whenever there are riots against the present capitalist system – whether politically motivated or just out of sheer frustration and anger about injustices in the society – where property is destroyed. Many, including the working class, in capitalist societies have an idea of the sanctity of property and no concept at all about the reasons for the ownership of such property.

Despite all efforts to hold them back the government troops were soon in control of increasingly large areas of the city and the slaughter continued. By the end of the week the ‘conservative’ estimate was that around 30,000 men women and children were murdered by the peasant Versailles troops. No proof was needed for active participation in the Commune, being in the wrong place and the wrong time was enough to merit the bullet or the bayonet of the soldiers.

But this was the aim of the reactionary forces. They were not concerned about capturing, taking to trial, convicting and punishing those who might have been elected members or active supporters of the Commune. The vary fact that the working class had permitted such an organisation and structure to exist in the first place was enough to deserve the death sentence. The reaction were not just thinking of those 70 days when the working class of Paris had taken control from their traditional rulers they were concerned that the working class of France (and indeed, the rest of the capitalist world) would be aware of the penalties for acting above their ‘station’.

Marx wrote about the importance of the working class being an independent armed force even before the blood of the Communards had been washed from the city’s streets;

All this chorus of calumny, which the Party of Order never fail, in their orgies of blood, to raise against their victims, only proves that the bourgeois of our days considers himself the legitimate successor to the baron of old, who thought every weapon in his own hand fair against the plebeian, while in the hands of the plebeian a weapon of any kind constituted in itself a crime. Karl Marx, The Civil War in France, FLPH, Peking, 1966, p99

The workers had taken up arms to better their condition and they were crushed by superior arms so that in future workers would be content to act within the bounds set by the ruling class itself. Fights and struggles around who should rule by depending upon the ballot box was to be the norm. It didn’t matter if people were to die in such internecine and tribal struggles (which is happening in many parts of the world even into the 21st century) as long as such fighting doesn’t challenge parliamentary cretinism – the belief that only by a cross on a piece of paper can society ever move forward.

By the 28th May the only fighting combatants of the Commune found themselves surrounded at the Père Lachaise cemetery, to the east of the city. One hundred and forty-seven were summary shot and buried in a trench – beside which today exists a simple monument to those murdered in that Bloody Week.

Communard’s Wall – Pere Lachaise

The repression didn’t finish when the shooting stopped. Thousands were arrested and about another 100 were shot ‘after due process. Many workers were imprisoned in various parts of France and 4,000 or so transported to New Caledonia, one of a group of islands that was part of the French Empire in the Pacific, 1,200 kilometres east of Australia, which at the time was a penal colony. (It’s still a French dependency to this day.) Included in their number was Louise Michel – probably the only ever decent anarchist.

Women of the Commune at Chantiers prison

Many lessons were taught in that short period of time in the spring of 1871 – both positive and negative – but, unfortunately, the example of the wrath and brutality of the ruling class has had a greater influence over the proletariat of the world than the shining example of courage, audacity and true freedom.

Only in a few cases have the workers (and this time in an alliance with the peasantry) got off their knees and attempted to establish a new world order. Internal problems and mistakes in those countries (and here I specifically talking about Russia, China, Albania – and perhaps Vietnam) led to the eventual demise of the socialist goal but the lack of proper, meaningful support in, especially, the so-called ‘advanced’ industrial countries meant that the burden, which would have been light if spread more widely, had to be taken on a relatively few shoulders.

Nonetheless, the same issues which caused the Parisian workers to take up arms and establish the Commune are the same under which most workers and peasants throughout the world still have to endure. There is no doubt they will rise and take control, but they will have to do so in a position of weakness, as did the Communards, as history has shown us that revolutions only occur at times of severe crisis – which inevitably mean not the best of circumstances under which to build socialism.

In 1848 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels wrote:

The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. (Karl Marx and Frederick Engels,The Manifesto of the Communist Party, FLP, Peking, 1968, p76).

What was true 160 years ago is as true today as it was then.

Eternal glory to the martyrs of the Paris Commune!