Mamayev Kurgan – 03

More on the USSR

Mamayev Kurgan – The Motherland Calls! – Stalingrad

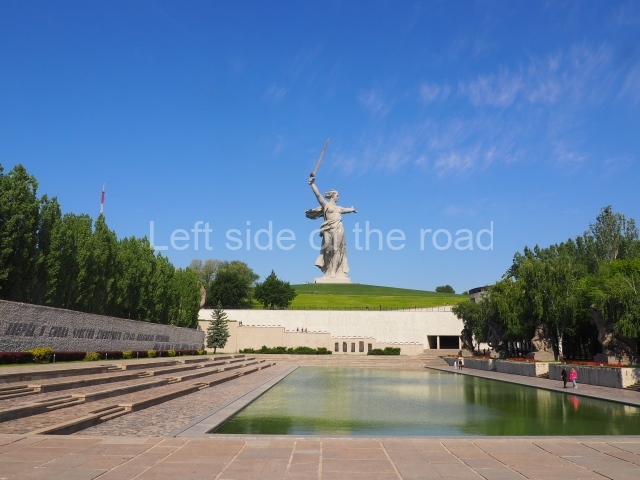

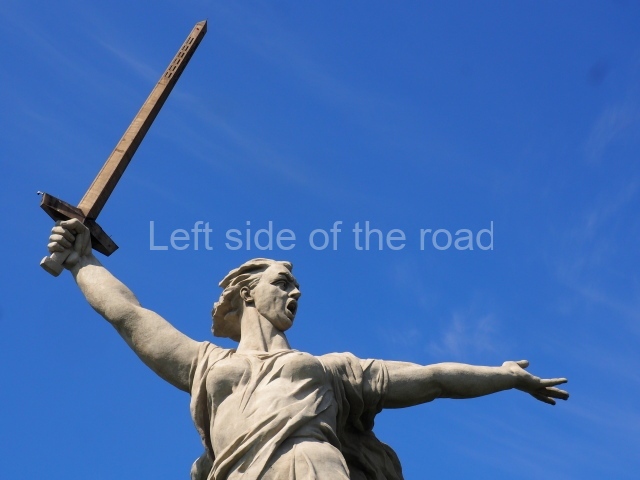

Mamayev Kurgan is the hillside complex commemorating the Battle of Stalingrad in the Great Patriotic War where the huge statue The Motherland Calls! is located.

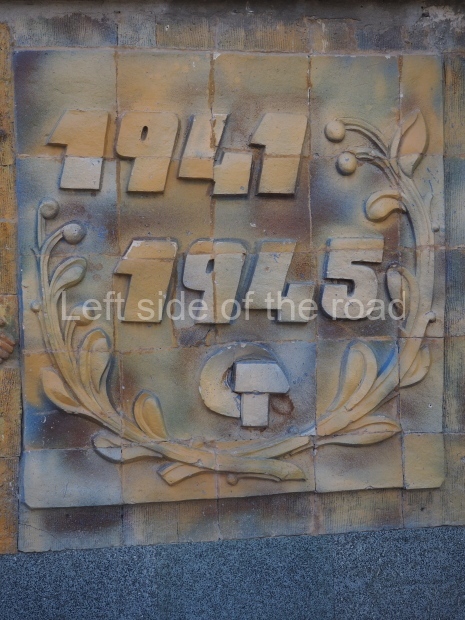

Mamayev Kurgan (Russian: Мама́ев курга́н) is a dominant height overlooking the city of Stalingrad (Volgograd) in Southern Russia. The name in Russian means ‘tumulus of Mamai’. The formation is dominated by a memorial complex commemorating the Battle of Stalingrad (August 1942 to February 1943). The battle, a hard-fought Soviet victory over Axis (Nazi) forces on the Eastern Front of the Great Patriotic War (World War II), turned into one of the bloodiest battles in human history. At the time of its installation in 1967 the statue, named The Motherland Calls, formed the largest free-standing sculpture in the world.

Mamayev Kurgan – 10

The Battle of Stalingrad

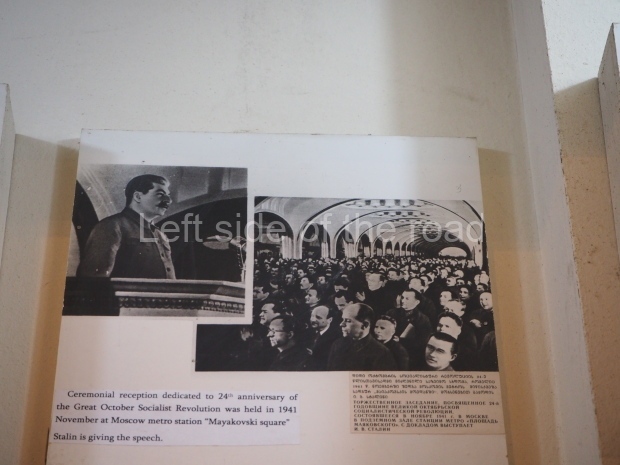

When forces of the German Sixth Army launched their attack against the city centre of Stalingrad on 13 September 1942, Mamayev Kurgan (appearing in military maps as ‘Height 102.0’) saw particularly fierce fighting between the German attackers and the defending soldiers of the Soviet 62nd Army. Control of the hill became vitally important, as it offered control over the city. To defend it, the Soviets had built strong defensive lines on the slopes of the hill, composed of trenches, barbed-wire and minefields. The Germans pushed forward against the hill, taking heavy casualties. When they finally captured the hill, they started firing on the city centre, as well as on the city’s main railway station under the hill. They captured the Volgograd railway station on 14 September 1942.

On the same day, the Soviet 13th Guards Rifle Division commanded by Alexander Rodimtsev arrived in the city from the east side of the river Volga under heavy German artillery fire. The division’s 10,000 men immediately rushed into the battle. On 16 September they recaptured Mamayev Kurgan and kept fighting for the railway station, taking heavy losses. By the following day, almost all of them had died. The Soviets kept reinforcing their units in the city as fast as they could. The Germans assaulted up to twelve times a day, and the Soviets would respond with fierce counter-attacks.

The hill changed hands several times. By September 27, the Germans again captured half of Mamayev Kurgan. The Soviets held their own positions on the slopes of the hill, as the 284th Rifle Division defended the key stronghold. The defenders held out until January 26 1943, when the counterattacking Soviet forces relieved them. The battle of the city ended one week later with an utter German defeat.

When the battle ended, the soil on the hill had been so thoroughly churned by shellfire and mixed with metal fragments that it contained between 500 and 1,250 splinters of metal per square meter. The earth on the hill had remained black in the winter, as the snow kept melting in the many fires and explosions. In the following spring the hill would still remain black, as no grass grew on its scorched soil. The hill’s formerly steep slopes had become flattened in months of intense shelling and bombardment. Even today, it is possible to find fragments of bone and metal still buried deep throughout the hill.

Memorial Complex

After the war, the Soviet authorities commissioned the enormous Mamayev Kurgan memorial complex. Vasily Chuikov, who led Soviet forces at Stalingrad, lies buried at Mamayev Kurgan; this makes him the only Marshal of the Soviet Union to be buried outside Moscow. 34,505 soldiers who were defenders of Stalingrad are buried there; sniper Vasily Zaytsev was also reburied there, in 2006.

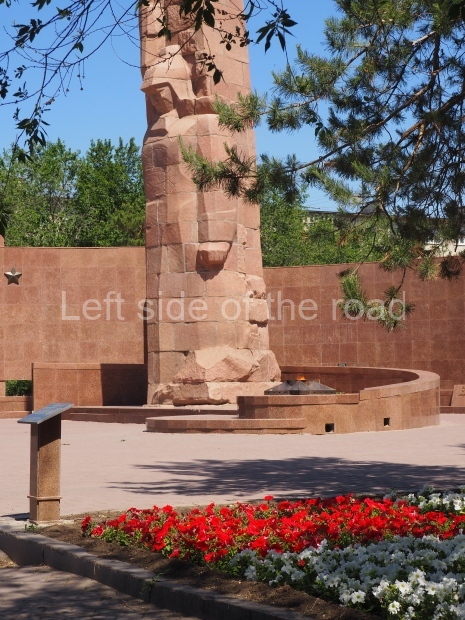

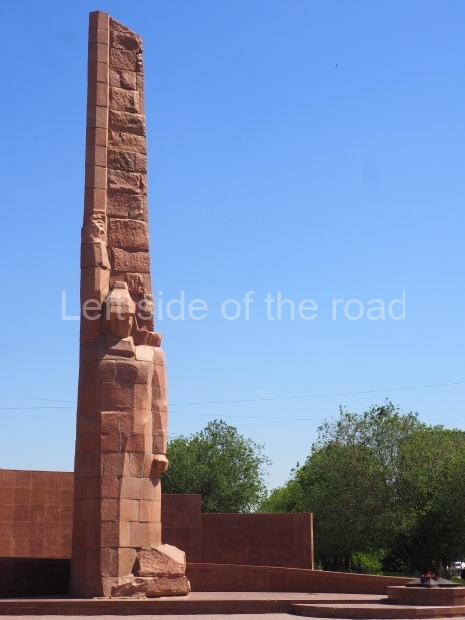

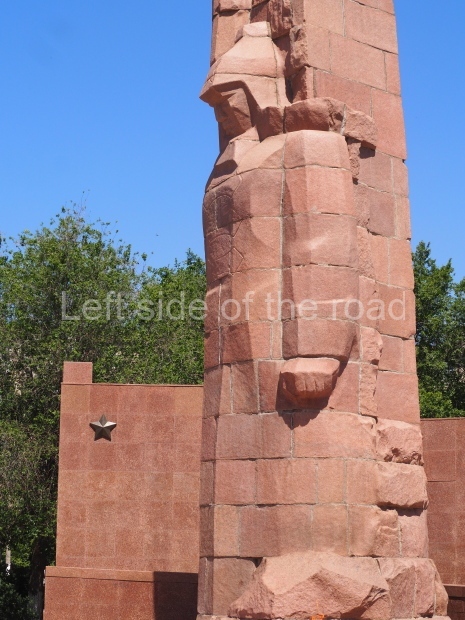

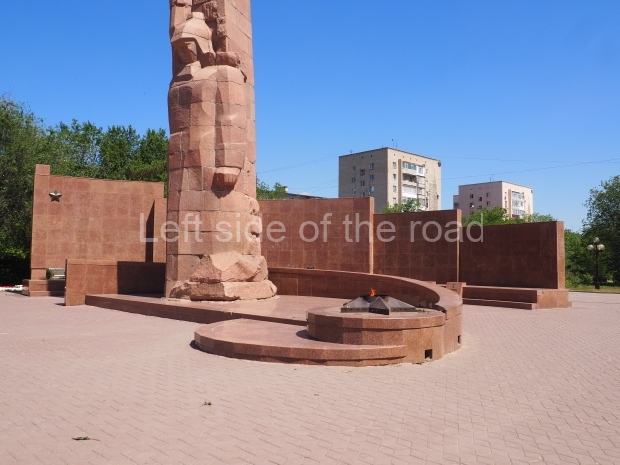

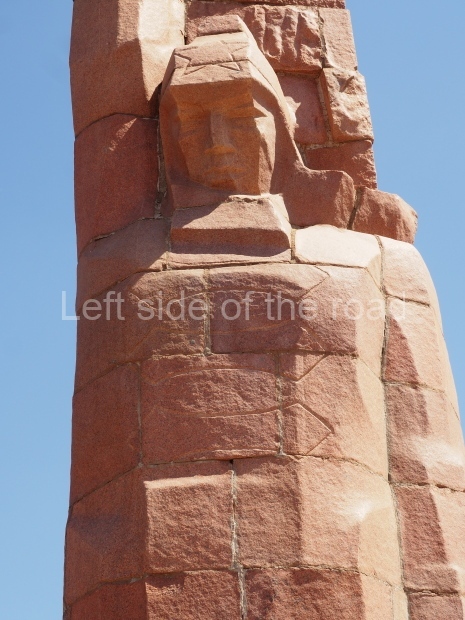

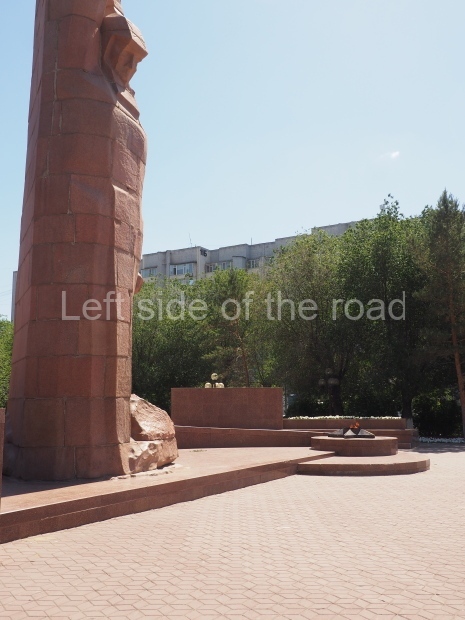

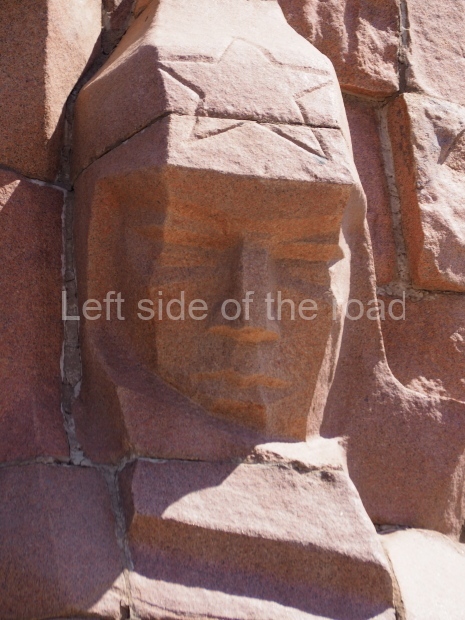

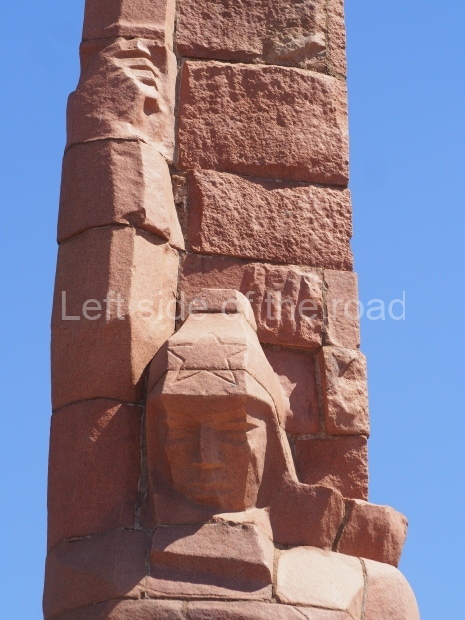

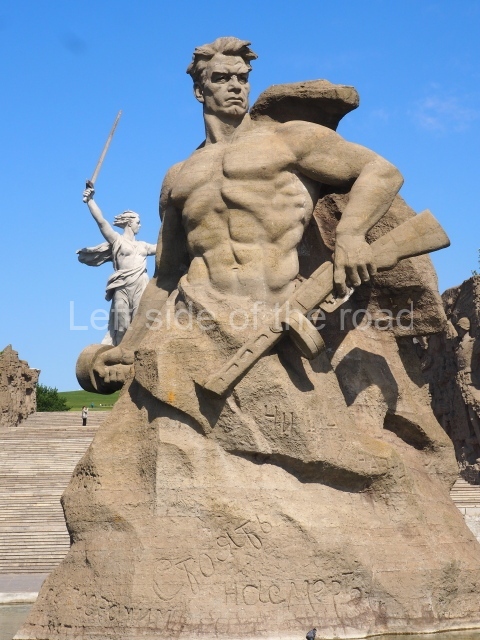

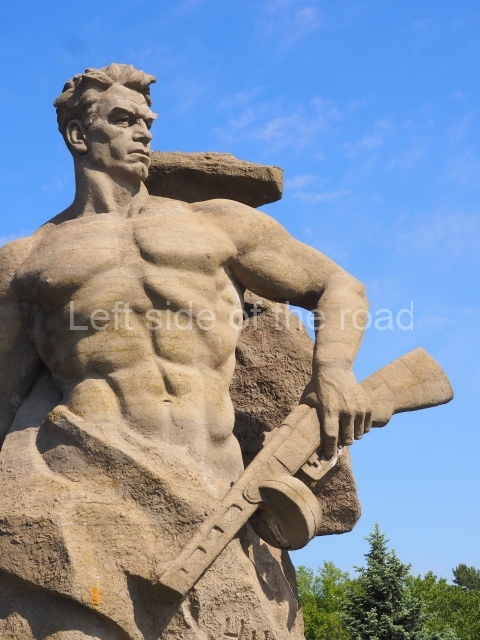

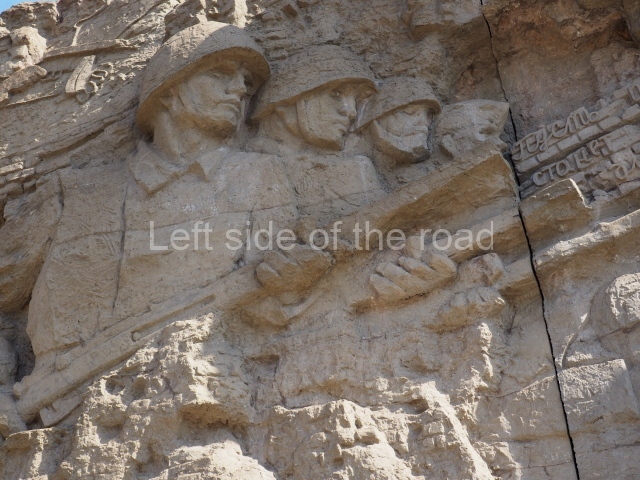

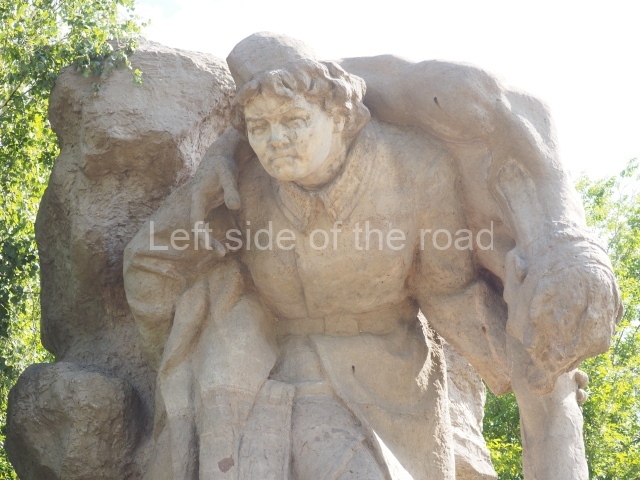

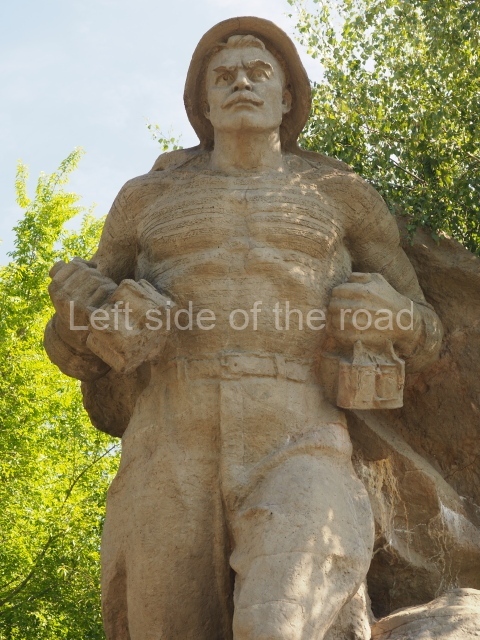

Avenue of Poplars; Stand To the Death!

Mamayev Kurgan – 11

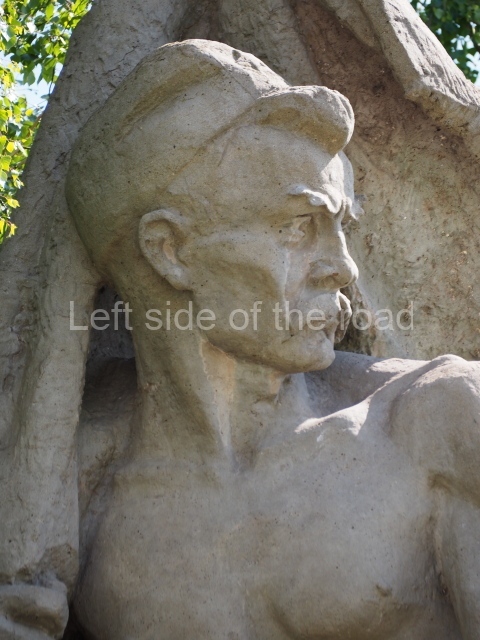

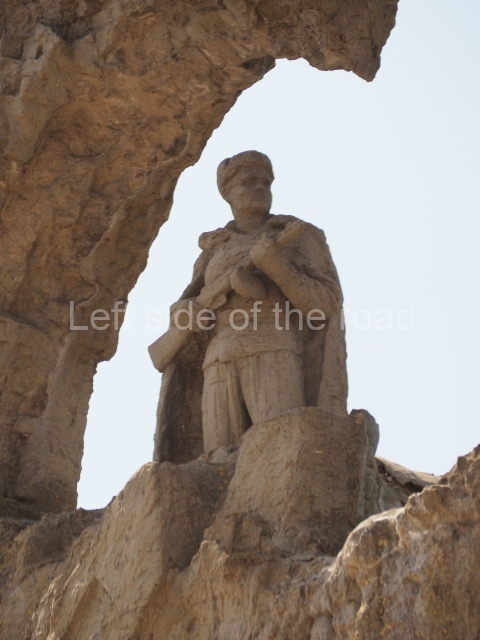

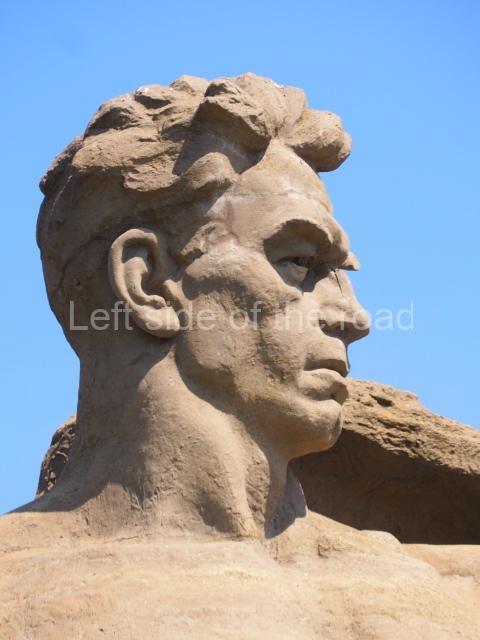

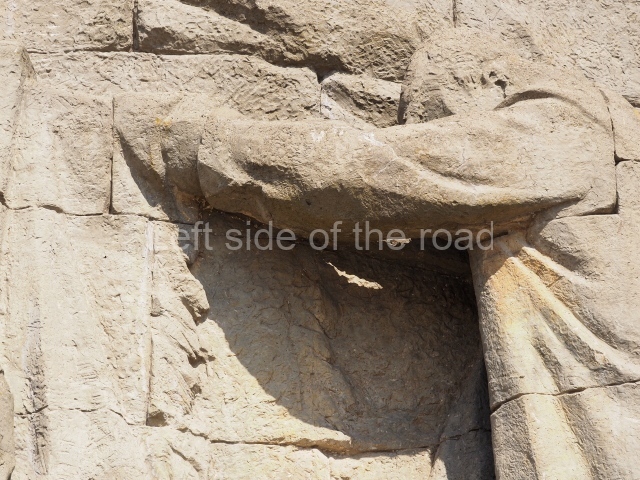

Mamayev Kurgan is accessible by a flight of stairs leading to the Avenue of Poplars, flanked on either side by poplar trees. From there, a second flight of steps leads to the statue of a muscular and shirtless Russian soldier. This statue, named Stand To the Death!, is carved from rock and surrounded by a large pool of water; it bears the inscription …And not a step back!

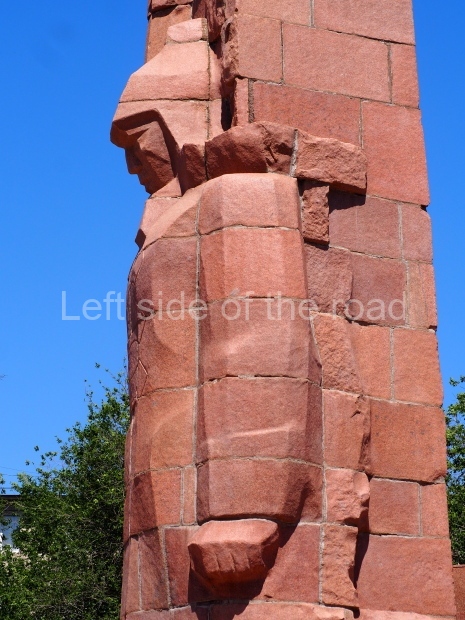

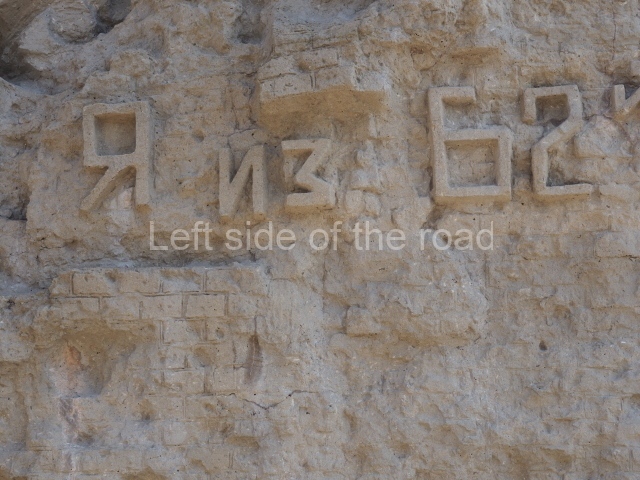

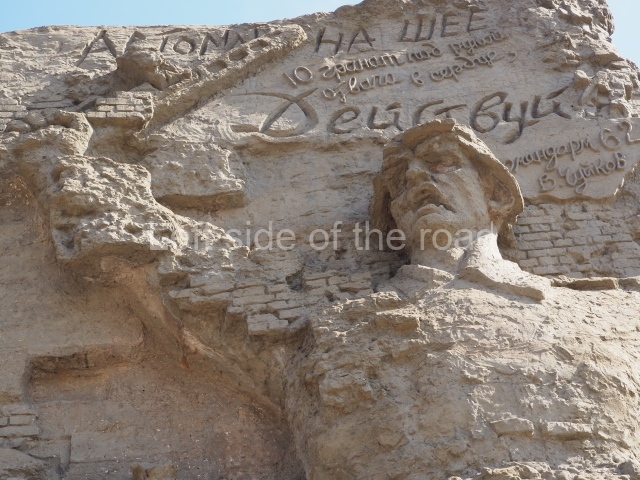

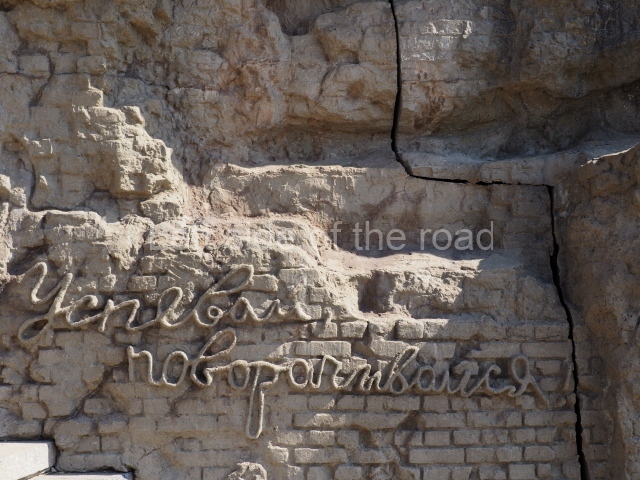

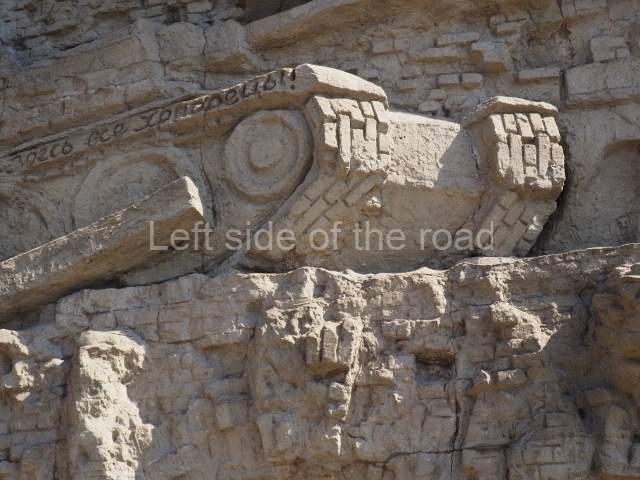

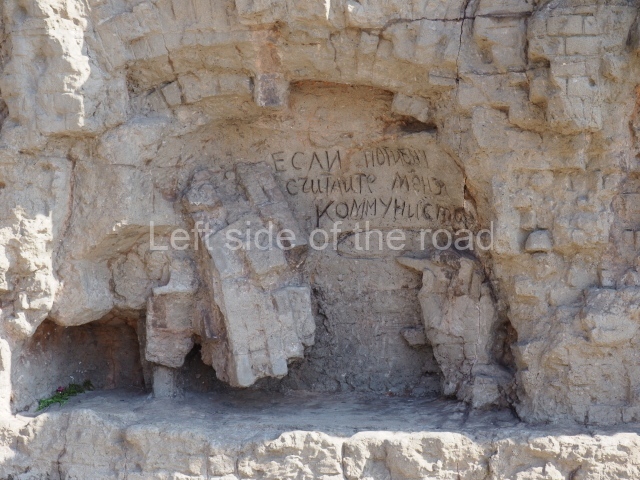

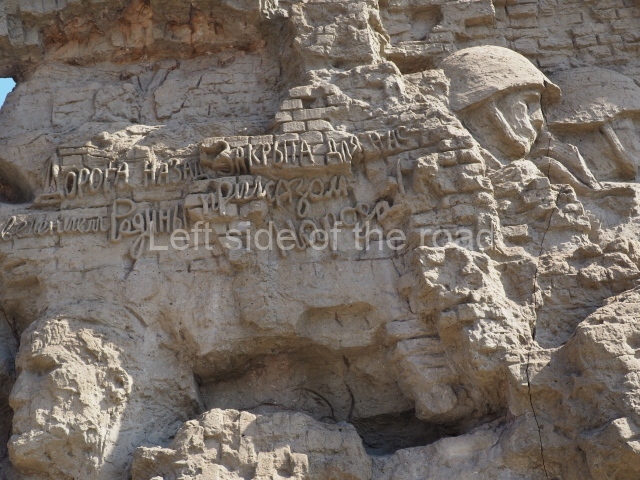

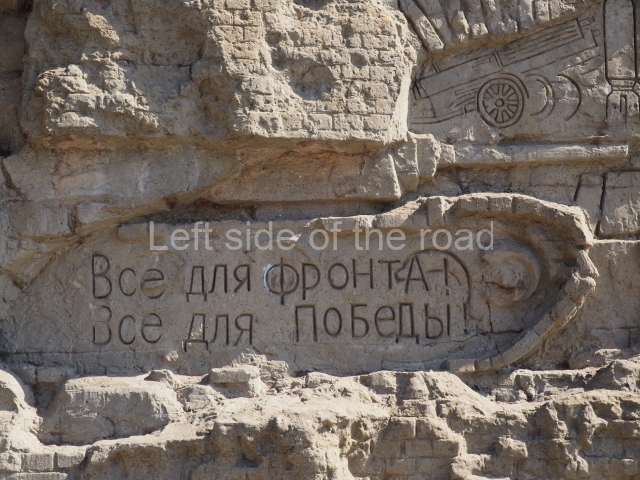

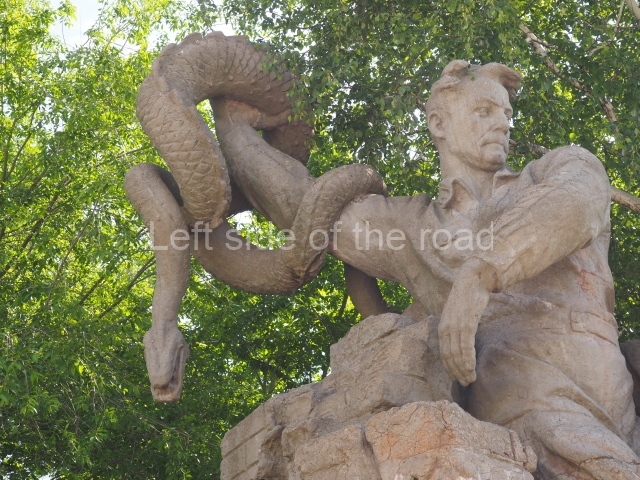

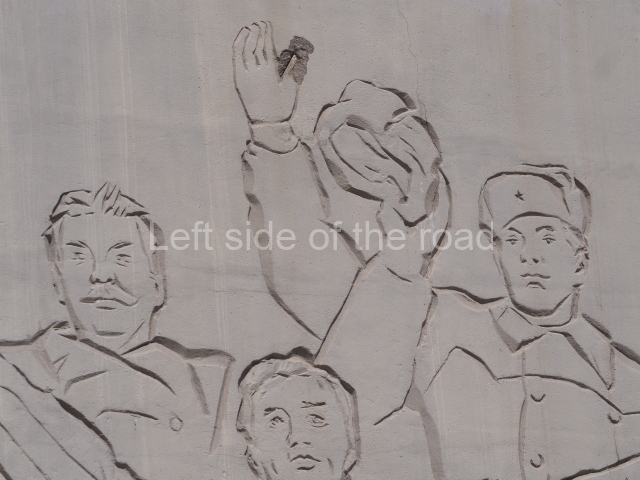

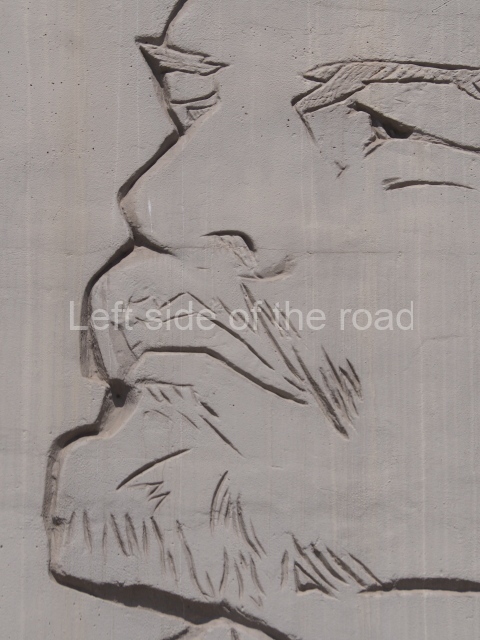

Symbolic Ruined Walls; Square of Heroes

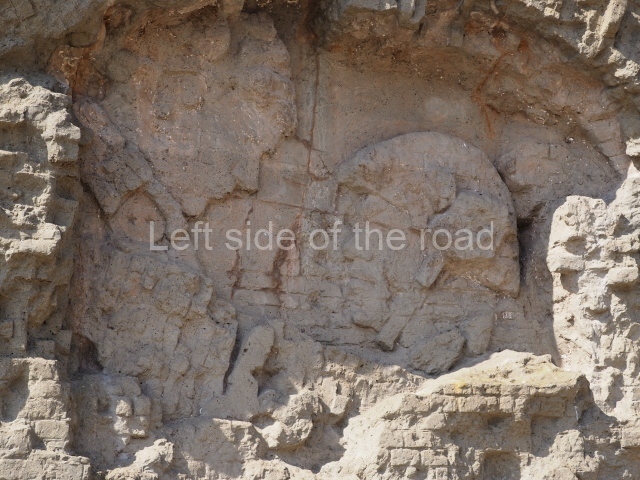

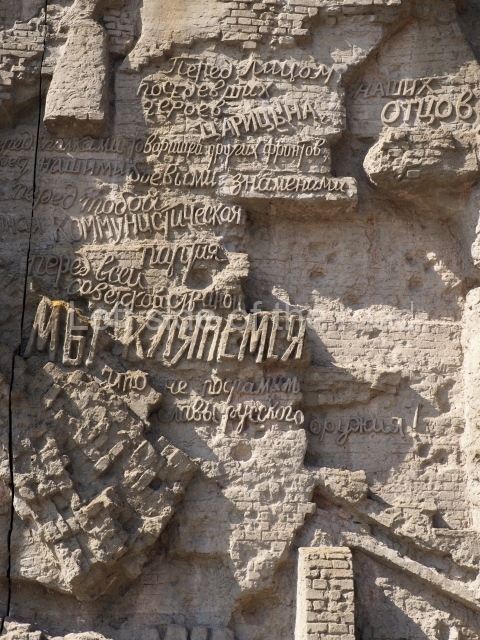

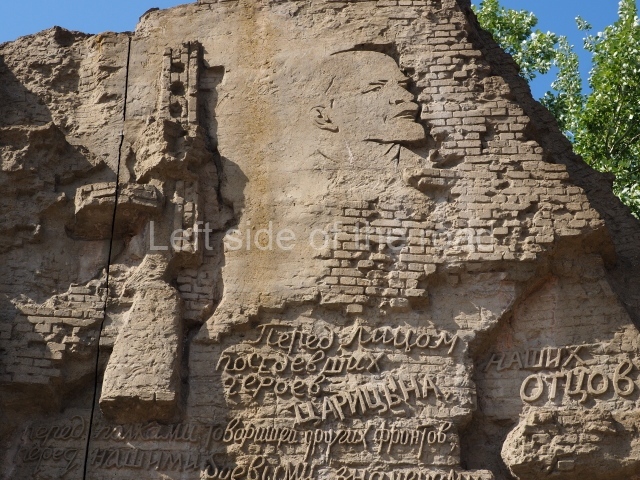

Mamayev Kurgan – 04

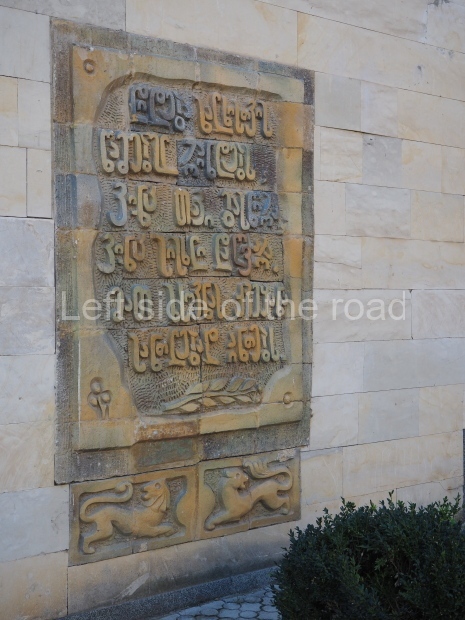

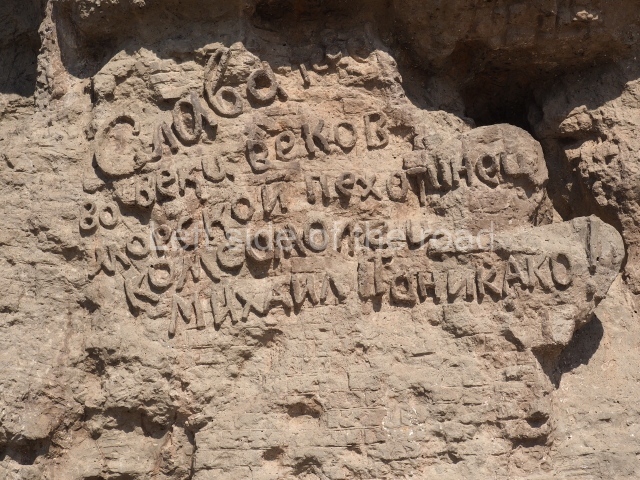

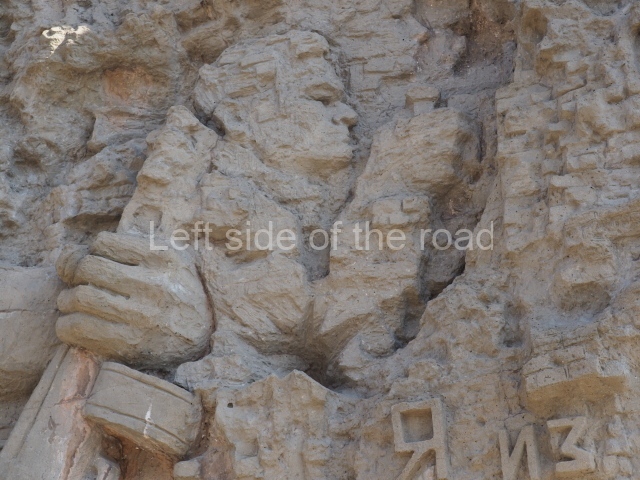

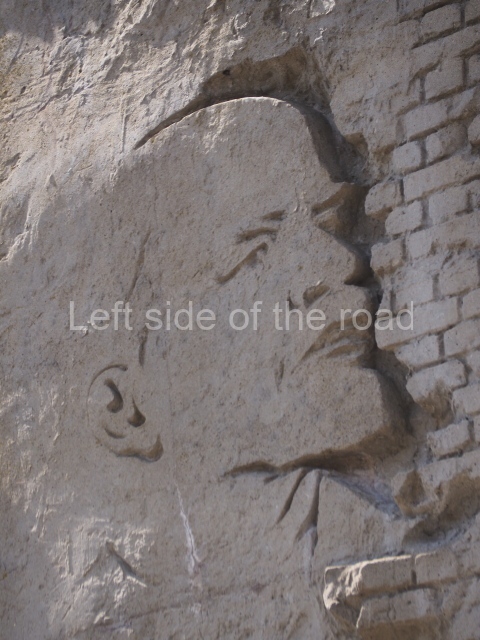

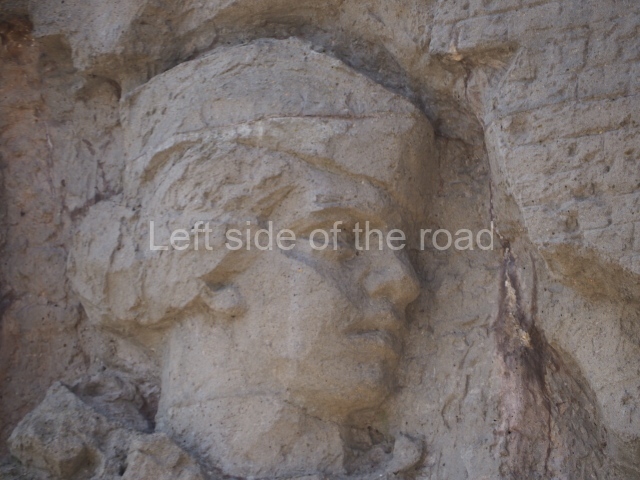

From Stand To the Death!, a third flight of stairs leads between the Symbolic Ruined Walls; these represent the ruins of Stalingrad, while immortalizing the Soviet heroes who defended the city. Carved into the walls are faces of numerous soldiers, their eyes closed to indicate death in battle. Also inscribed on the walls are numerous quotes from actual defenders of Stalingrad; these words were originally carved, by the soldiers themselves, upon the sides of various ruined buildings throughout the city.

Atop the steps, past the walls, is the Square of Heroes; this is dominated by another large pool of water. On one side of the pool is a wall bearing this inscription: ‘With an iron wind blowing straight into their faces, they were still marching forward; and fear seized the enemy. Were these people who were attacking? Were they even mortal at all?’ On the other side of the pool are six sculptures, the first of which bears the inscription: ‘We’ve stood out and defeated death’. The second and third sculptures commemorate military nurses and, respectively, marines. The fourth sculpture is dedicated to the officers who led the battle to protect Stalingrad. The fifth sculpture tells the story of ‘Saving the Banner’. The sixth sculpture commemorates the eventual triumph of the Russian army over the Germans.

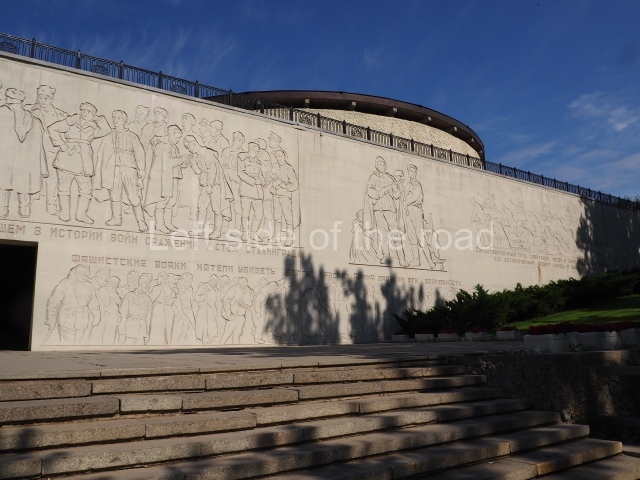

Hall of Military Glory

Mamayev Kurgan – 08

Past the Square of Heroes is the Hall of Military Glory, whose outer façade is decorated with Russian artwork of Soviet soldiers celebrating the war’s end…and with the inscription ‘Our people will keep alive their memory of the greatest battle in the history of warfare, within the walls of Stalingrad’.

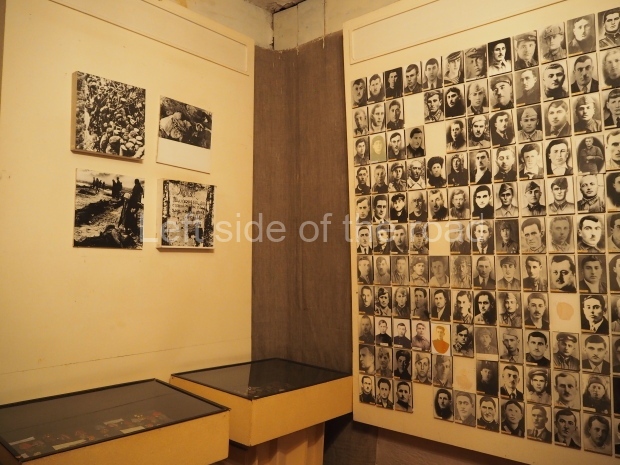

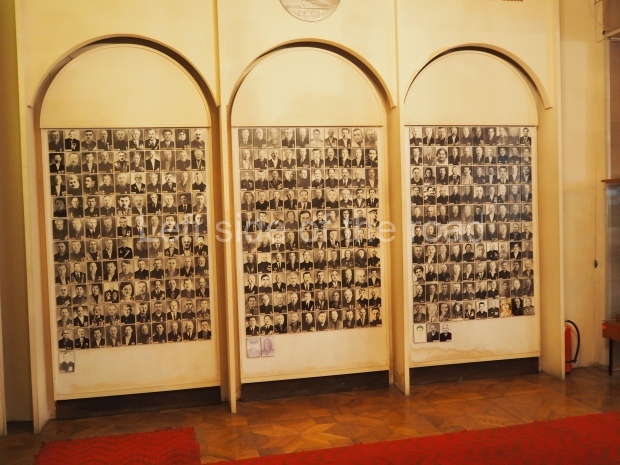

An indoor flight of stairs leads to the Hall’s circular main chamber; at the chamber’s centre is the Eternal Flame, a large sculpture of a hand holding a torch. The Eternal Flame is constantly under armed guard, which is changed every hour. The main chamber is considered sacred ground, with mournful music being played on a loop; out of respect, visitors are strongly discouraged from speaking aloud. The chamber’s walls are covered in glass-foil mosaics; these bear the names of 7,200 Russian soldiers who died in the battle for Stalingrad. Around the ceiling of the chamber is the following inscription: ‘…Yes, we were mere mortals, and few of us survived (the German siege). But we all fulfilled our patriotic duty to our sacred Motherland’.

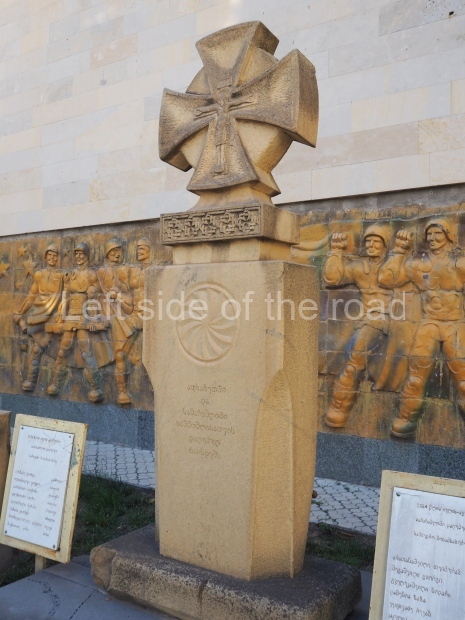

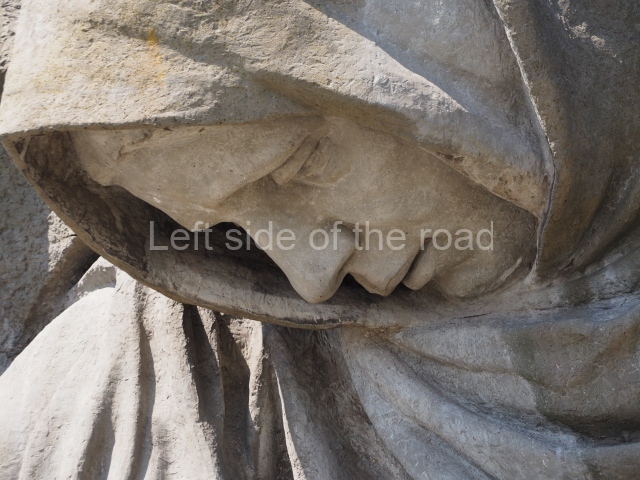

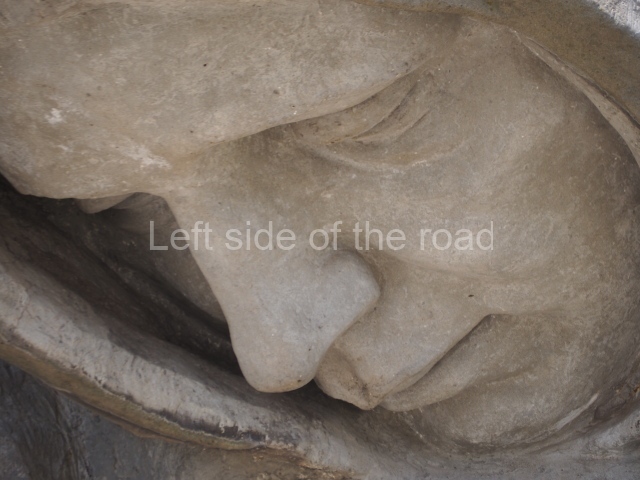

Mother’s Sorrow

Mamayev Kurgan – 07

The hall’s upper exit leads to the base of a pathway, which in turn zigzags uphill to the Motherland is Calling! statue itself. Also at the hill’s base is a third shallow pool, this one surrounding a stone monument named Mother’s Sorrow.

The hill itself is an unmarked grave for over 34,500 Russian troops killed at Stalingrad; even this is a tiny percentage of the overall Soviet casualties from the battle. The grass on the hill is considered sacred, and visitors are forbidden to step on it. The top of the hill gives a panoramic view of the city of Stalingrad (Volgograd).

Mamayev Kurgan is open to the public 24 hours a day, and there is no charge for admission.

Background

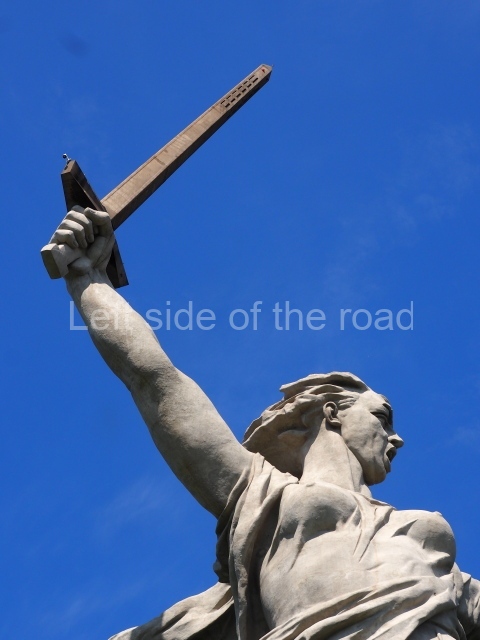

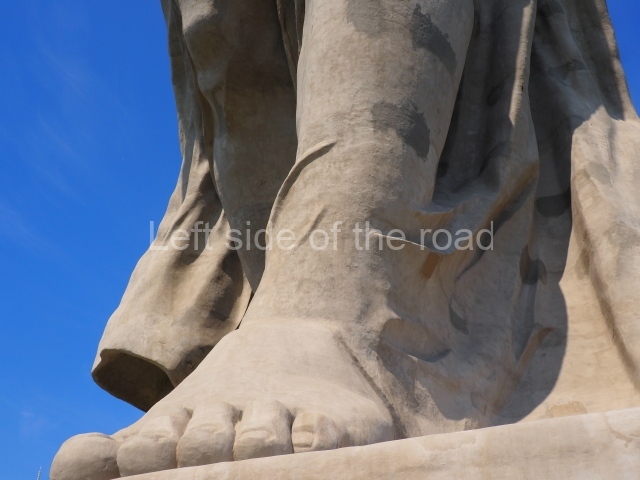

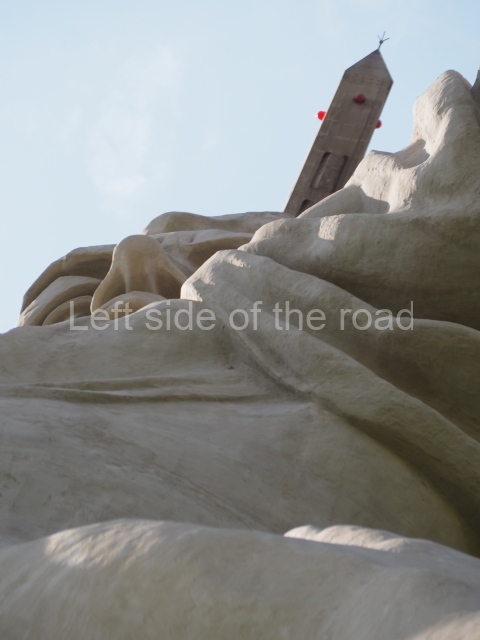

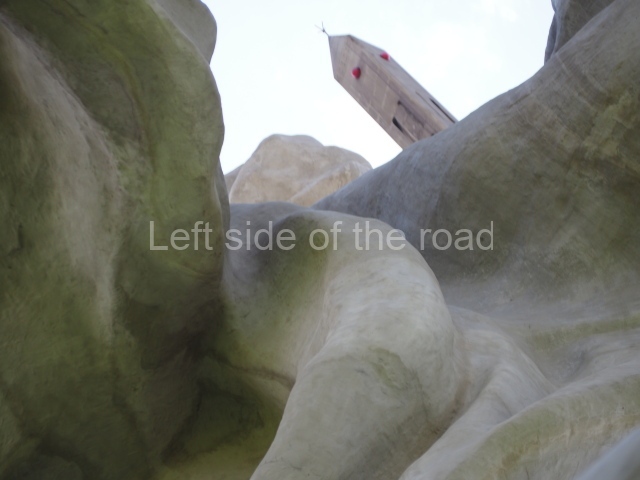

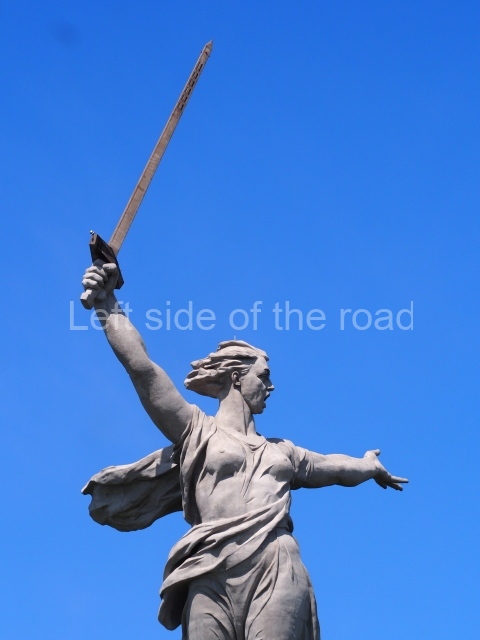

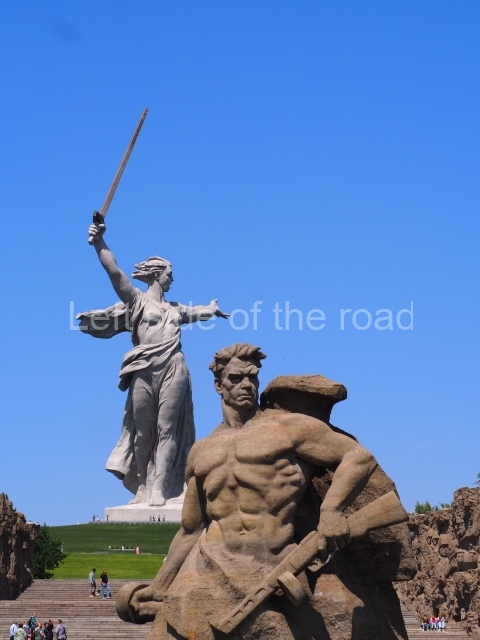

The monumental memorial was constructed between 1959 and 1967, and is crowned by a huge allegorical statue of the Motherland on the top of the hill. The monument, designed by Yevgeny Vuchetich, has the full name The Motherland Calls! (Russian: Родина-мать зовёт! Rodina Mat Zovyot!). It consists of a concrete sculpture, 52 meters tall, and 85 meters from the feet to the tip of the 27-meters sword, dominating the skyline of the city of Stalingrad (later renamed Volgograd).

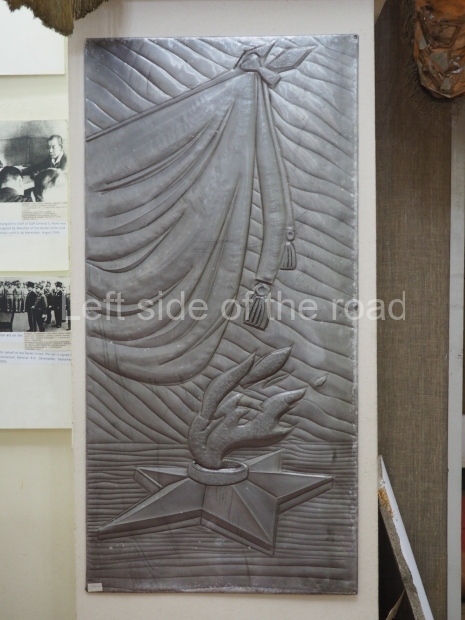

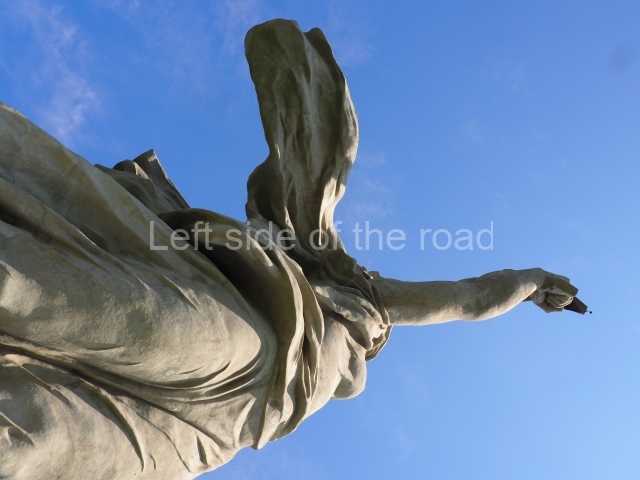

The construction uses concrete, except for the stainless-steel blade of the sword, and is held on its plinth solely by its own weight. The statue is evocative of classical Greek representations of Nike, in particular the flowing drapery, similar to that of the Nike of Samothrace.

The above text from Wikipedia.

‘The Motherland Calls’, Volgograd

Mamayev Kurgan – 01

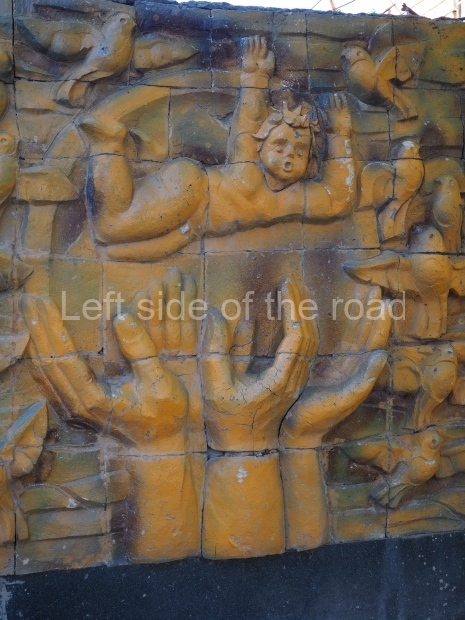

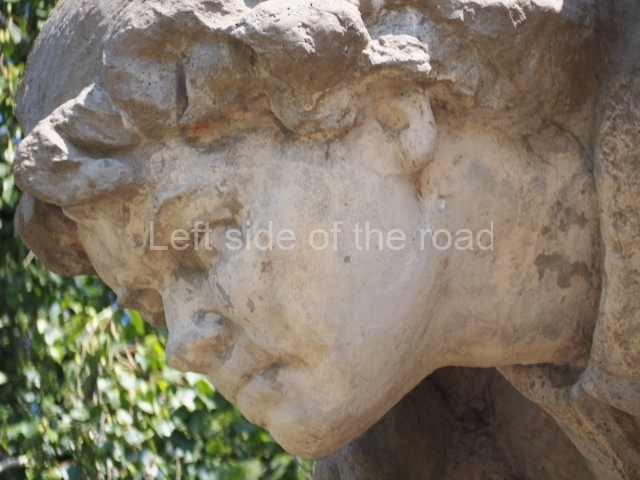

Mamayev Kurgan is not the site of a single monument, but of a complex of monuments, each more gigantic than the last. … At the foot of the hill stands a huge sculpture of a bare-chested man clutching a machine gun in one hand and a grenade in the other. He seems to rise out of the very rock, torso rippling, as tall as a three-storey building. Beyond him, on either side of the steps that lead to the summit, are relief sculptures of giant soldiers springing out of the ruined walls as if in the midst of battle. Farther up the hill is the gigantic figure of a grieving mother, more than twice the size of my house. She is hunched over the body of her dead son, sobbing into a large pool of water, called the ‘Lake of Tears:

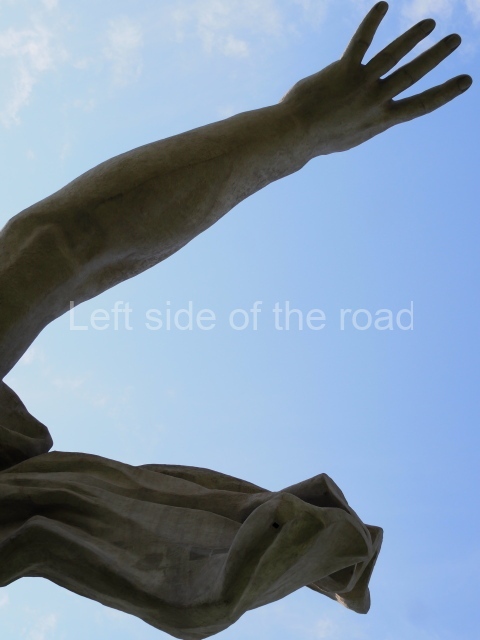

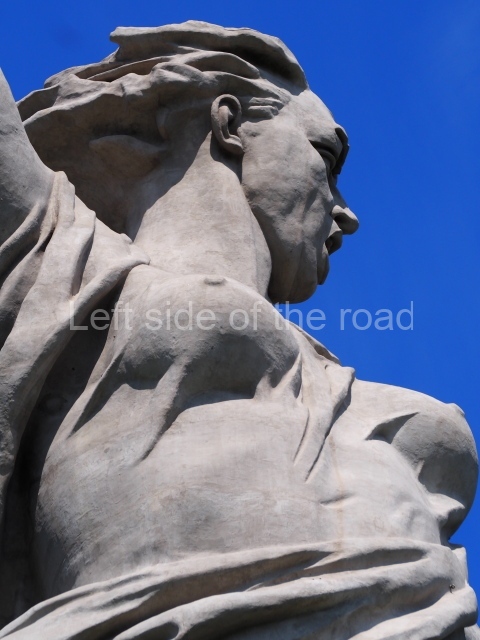

The dozens of statues arranged in this park are all giants: not one of them is under six metres (20 feet) tall, and some of them depict heroes three or four times that size. And yet they are dwarfed by the single statue that rises above them all, on the summit of the hill. Here, overlooking the Volga, stands a colossal representation of Mother Russia beckoning to her children to come and fight for her. Her mouth is open in battle cry, her hair and dress fluttering in the wind; and in her right hand she holds a vast sword pointing up into the sky. From her feet to the tip of her sword she stands 85 metres (280 feet) high. She is nearly twice as tall, and forty times as heavy, as the Statue of Liberty in New York City. When she was first unveiled in 1967, she was the largest statue in the world.

This memorial, entitled ‘The Motherland Calls!; is one of Russia’s most iconic statues. It was the creation of Soviet sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich, who spent years designing and building it. It contains around 2,500 metric tonnes of metal and 5,500 tonnes of concrete. The sword alone weighs 14 tonnes. So huge was the statue that Vuchetich was obliged to collaborate with a structural engineer, Nikolai Nikitin, to ensure that it did not collapse under its own weight. Holes had to be drilled into the sword to reduce the threat of the wind catching it and causing the whole structure to sway.

Mamayev Kurgan – 09

Were this monument in Italy or France it would appear absurdly grandiose, but here on the banks of the Volga, in the city that was once called Stalingrad, it feels quietly appropriate. The battle that took place here in 1942 dwarfs anything that happened in the West. It began with the greatest German bombardment of the war, and progressed with attacks and counterattacks by more than a dozen entire armies. Within the city itself, soldiers fought from street to street, and even from room to room, in a landscape of shattered houses. Over the course of five months around two million men lost their lives, their health or their liberty. The combined casualties of this one battle were greater than the casualties that Britain and America together suffered during the whole of the war.

As one stands on the summit of Mamayev Kurgan in the shadow of the gigantic statue of the Motherland, one can feel the weight of all this history. … for many Russians this place is sacred. The word ‘Kurgan’ in Russian means a tumulus or burial mound. The hill is an ancient site dedicated to a fourteenth-century warlord, but in the wake of the greatest battle of the greatest war in history, it carries a new symbolism. This place was one of the major battlegrounds of 1942, and an unknown number of soldiers and civilians are buried here. Even today, when walking on the hill, it is possible to find fragments of metal and bone buried in the soil. The Motherland statue stands, both figuratively and literally, upon a mountain of corpses.

Mamayev Kurgan – 05

The scale of the war in Russia is one reason why the monuments on Mamayev Kurgan are so huge, but it is not the only reason – in fact, it is not even the main reason. The statues of muscular heroes and weeping mothers might be huge, but it is the giantess on the summit of the hill that dominates them all. It is important to remember that this is a representation not of the war, but of the Motherland. Its message is simple: no matter how great the battle, and no matter how great the enemy, the Motherland is greater still. Her colossal size is supposed to be a comfort to the struggling soldiers and weeping mothers, a reminder that for all their sacrifice, they are at least a part of something powerful and magnificent. This is the true meaning of Mamayev Kurgan.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the people of the Soviet Union had little to console them. Not only were they traumatised by loss, but they also faced an uncertain future. Russians did not benefit economically from the war as the Americans did: the violence had left their economy in ruins. …

Mamayev Kurgan – 12

The only consolation offered to Russian and other Soviet people was that their country had proven itself at last to be a truly great nation. In 1945, the USSR possessed the largest army the world has ever seen. It dominated not only the vast Eurasian land mass, but also the Baltic and the Black Sea. The Second World War had not only restored the country’s borders, but extended them, both to the west and to the east, and Soviet influence now stretched deep into the heart of Europe. Before the war, the Soviet Union had been a second rate power, weakened by internal upheaval. After the war, it was a superpower.

The Motherland statue on Mamayev Kurgan was designed to be proof of all this. It was built in the 1960s, when the USSR was at the height of its strength. It stood as a warning to anyone who dared attack the Soviet Union, but also as a symbol of reassurance to the Soviet people. The giant, it declared, would always protect them.

Mamayev Kurgan – 06

For the Russian citizens who first stood on the summit of this hill with the Motherland statue at their backs, the vistas looked endless. Everything to the west of them for a thousand miles was Soviet territory. To the east they could travel through nine time zones without once leaving their country. Even the heavens seemed to belong to them: the first man in space was a Russian, and the first woman too. It is impossible to look up at the Motherland statue without also gazing beyond, to the endless skies above her.

From; Prisoners of history – what monuments to the Second World War tell us about our history and ourselves, Keith Lowe, William Collins, London, 2020, pp6-9.

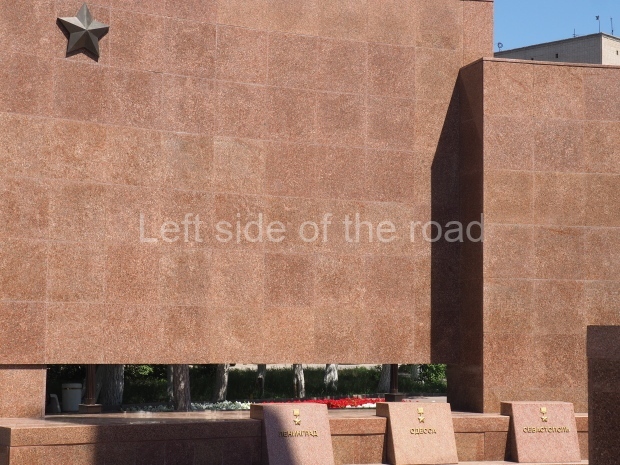

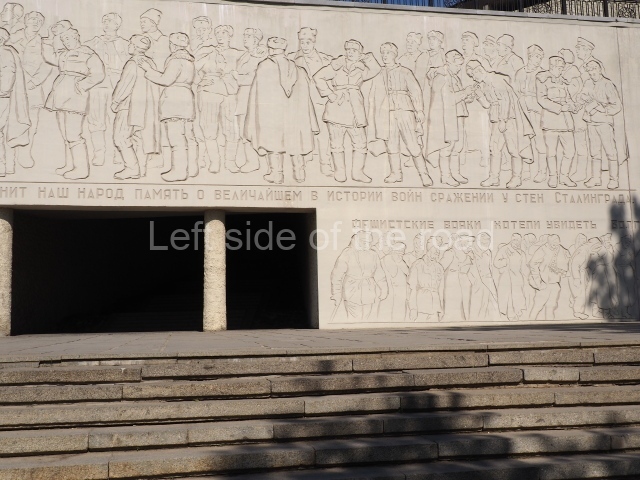

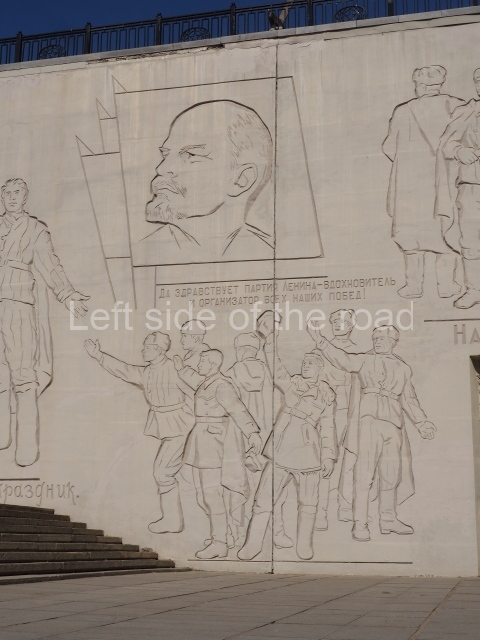

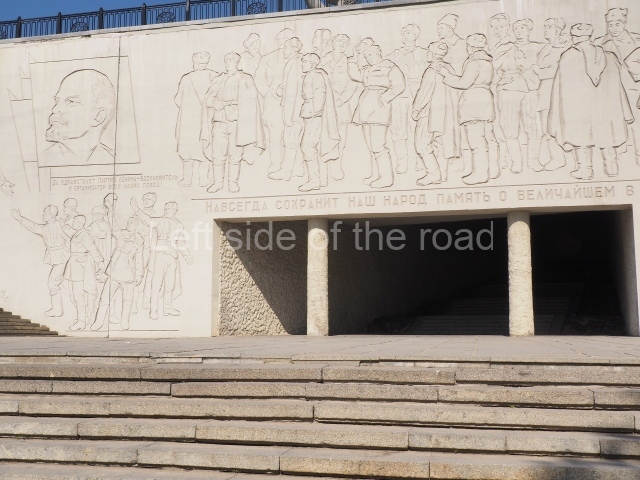

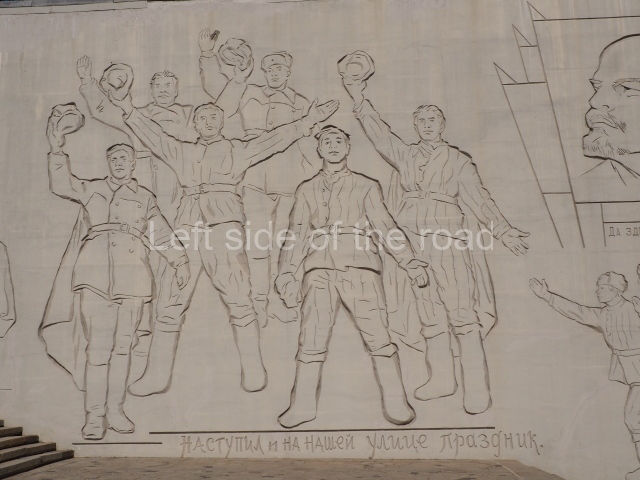

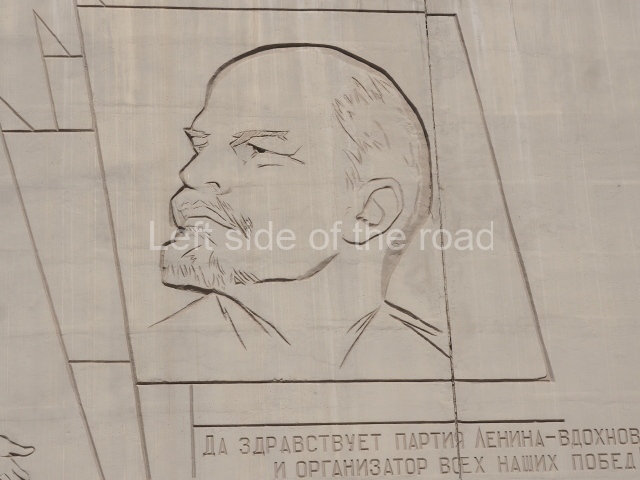

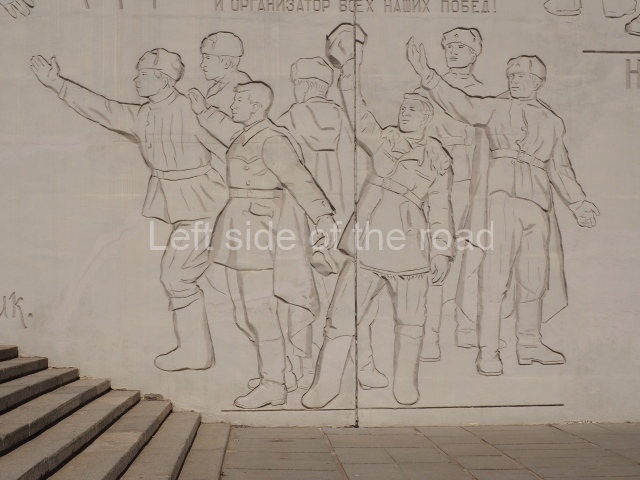

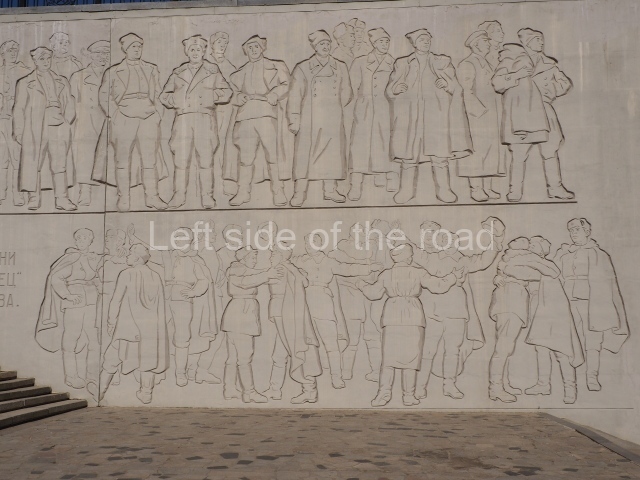

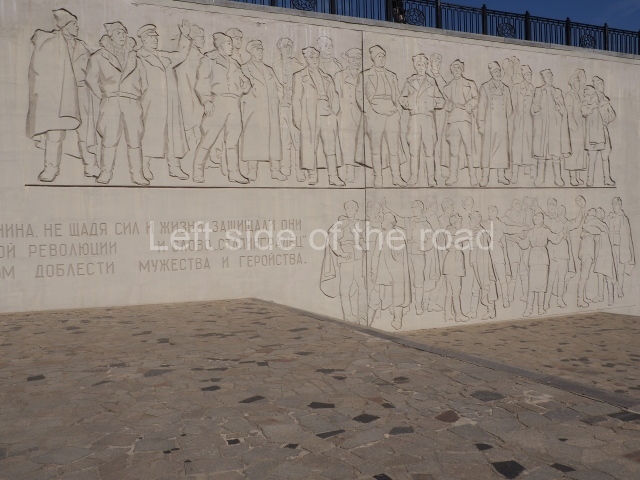

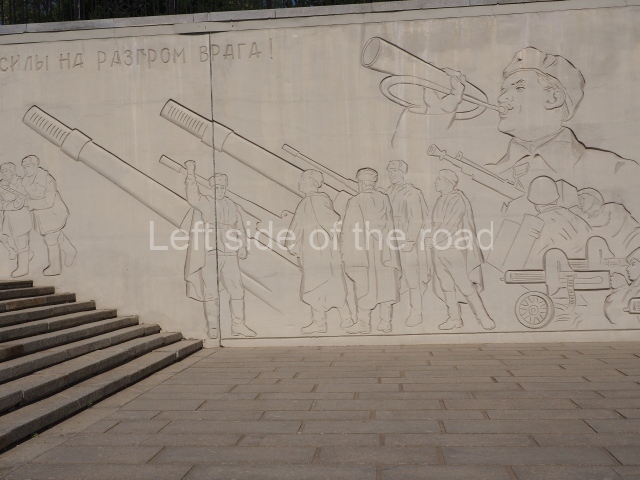

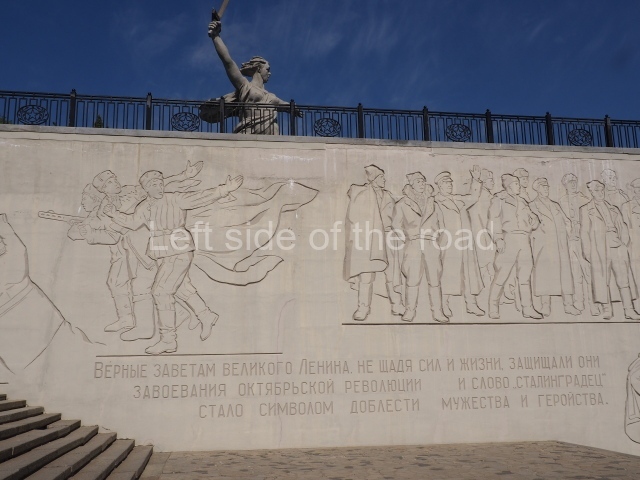

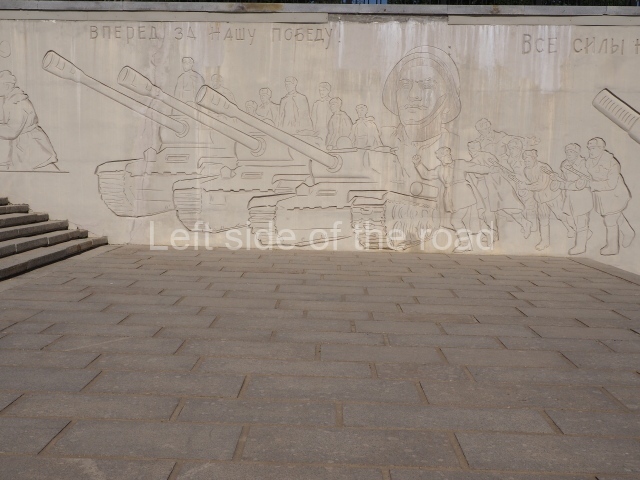

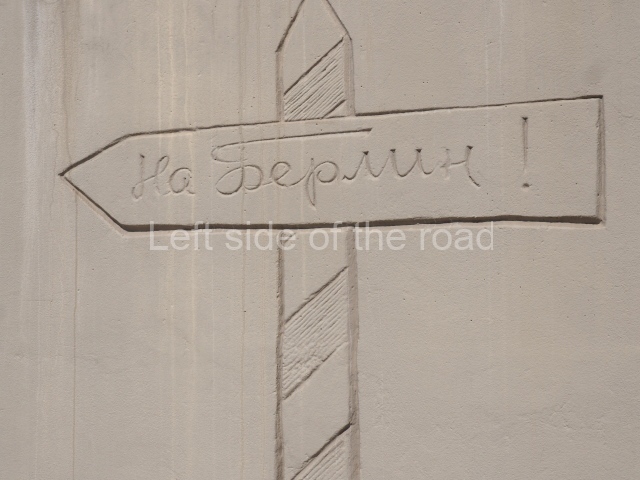

Memory of Generations

Mamayev Kurgan – 02

Located in the entrance square, to the right of the steps which lead up to the monument, is another large sculpture called ‘Memory of Generations’. This depicts Stalingraders arriving to visit the monument, carrying flowers and a large wreath, and the images represent both pride and sorrow at the sacrifice of the defenders of the city.

Marshal Zhukov’s memoirs of The Battle of Stalingrad.

Related;

Stalingrad (Volgograd) Railway Station

Children and crocodile fountain – Railway station square

Designed by;

Yevgeny Vuchetich, Yakov Belopolsky and Nikolai Nikitin.

Unveiled;

15 October 1967

Location;

Just over 3 kilometres north-west of the city centre, opposite the Volgograd Arena.

GPS;

48°44′33″N

44°32′13″E

How to get there;

Buses heading north-west along VI Lenin Avenue pass by the base of the steps to the monument. Also the Metro has a stop at Mamayev Kurgan.

Opening times;

It is never closed.

More on the USSR