Kabah – Yucatan

Location

This is rated as a second-class city in the Atlas arqueologico del estado de Yucatan, although the authors state that the overall mass of formal structures appears to be greater at Kabah than at the neighbouring first-class city of Uxmal. In the archaeological literature, Uxmal is regarded as the capital of the regional political system on which other cities such as Kabah depended. Kabah stands out among the great urban centres in the north-western Puuc mountains due to its strategic location at the southern tip of the axis formed by the cities of Uxmal and Nohpat, with which it shared close kinship ties.

It is situated 120 km from Merida on the old ‘via ruinas’ Campeche road, 22 km from Uxmal, the most important archaeological centre in the Puuc region, and just 6 km from the town of Santa Elena, the ancient Nohcacab. Kabah lies at the south end of a sacbe that links it to Nohpat and Uxmal, and very probably to Oxkintok further north; situated to the south-east of Kabah are the cities of Sayil, Xlapak and Labna, and other minor sites such as Chetulich and Mulchic, the latter famous for its battle-scene mural painted in the mid-9th century and currently on display at the Canton de Merida Museum-Palace.

Kabah is located in a hilly area and it is common to find the residential groups of the settlement in these natural elevations; mainly, however, the city is covered by semi-evergreen seasonal forest. There is no surface water but the permeability of the soil has given rise to underground rivers, which meant that the ancient inhabitants must have had to go to deep caves to obtain water; they would also have stored rainwater in the natural depressions and in chultunes or cisterns, built in the shape of an inverted funnel, which collected water in the plazas.

By virtue of a state decree in 1993, Kabah became a protected natural area: in addition to safeguarding the historical and cultural merits of the site, this status ensures protection of the ecological conditions and promotes the social development of the town of Santa Elena.

Site description

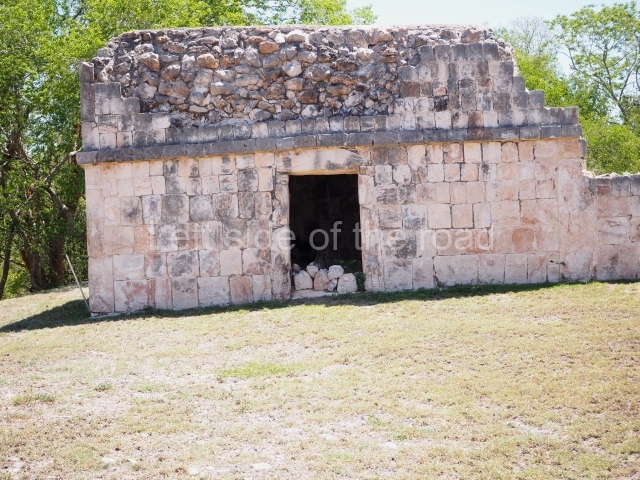

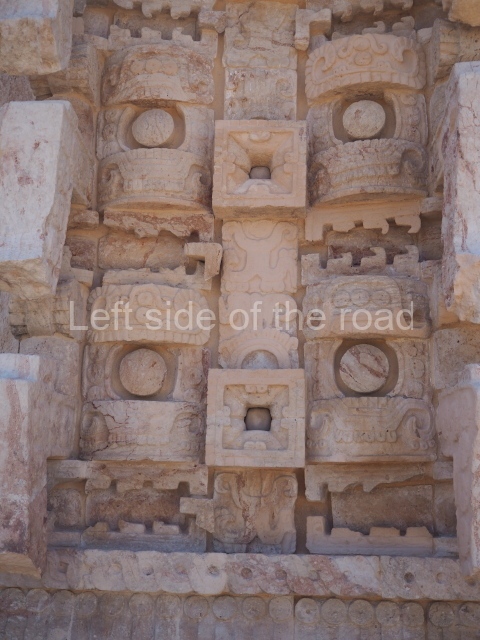

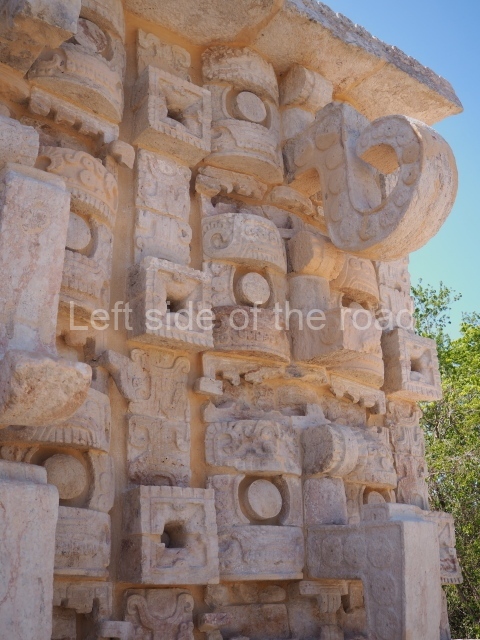

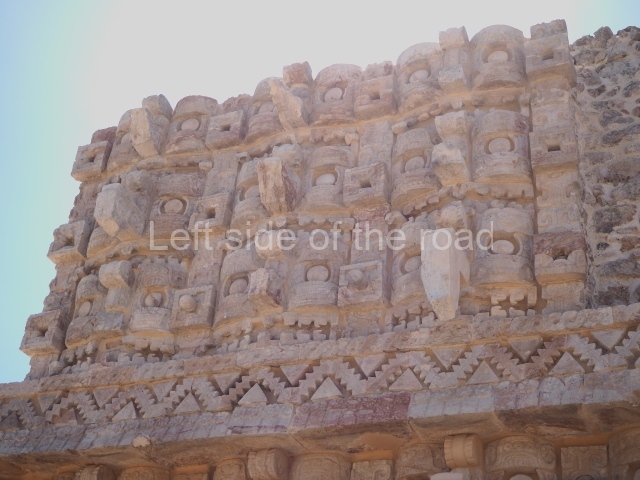

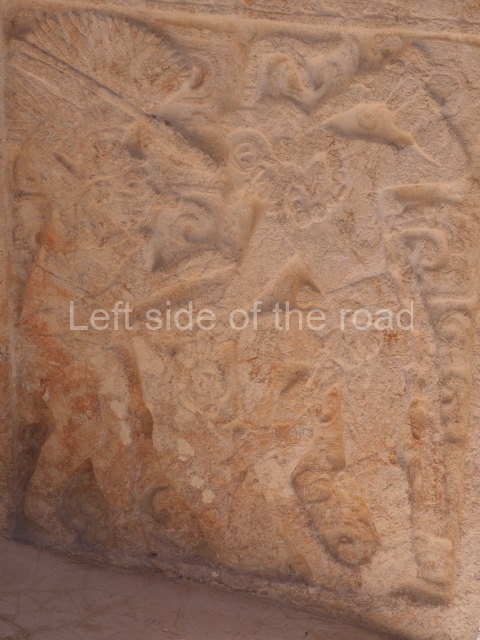

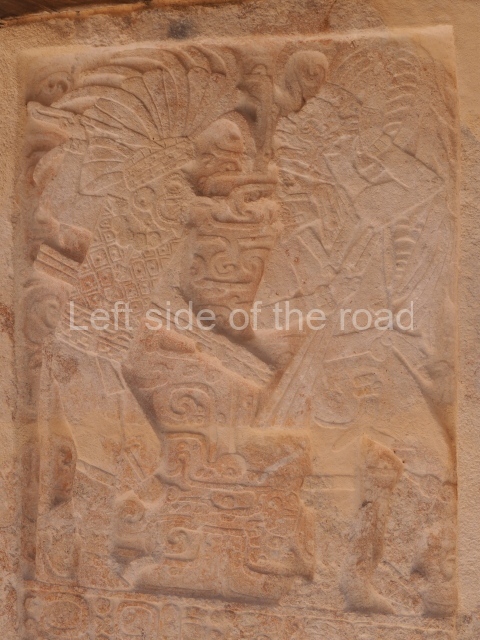

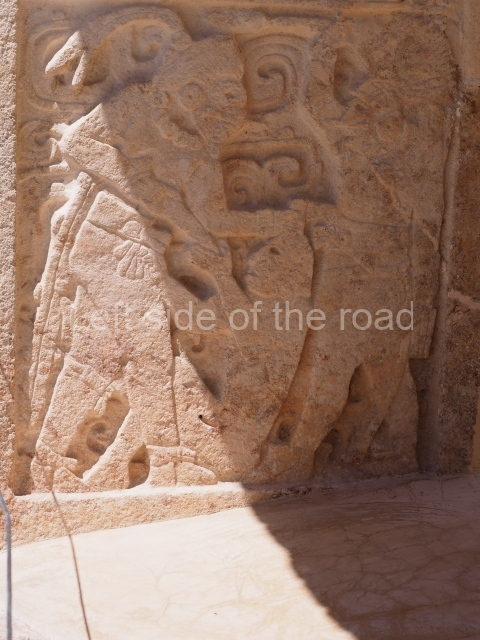

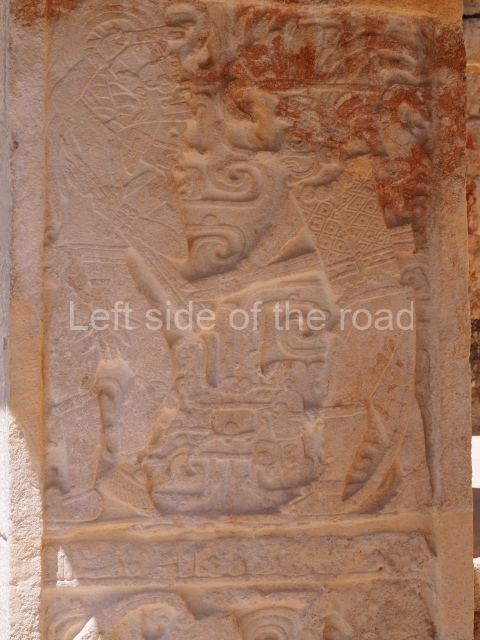

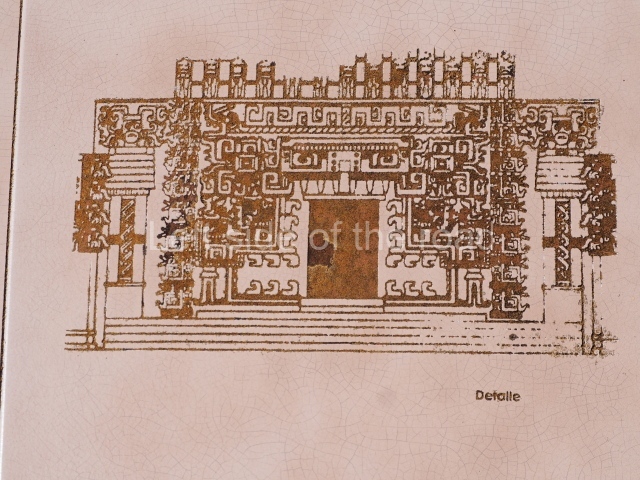

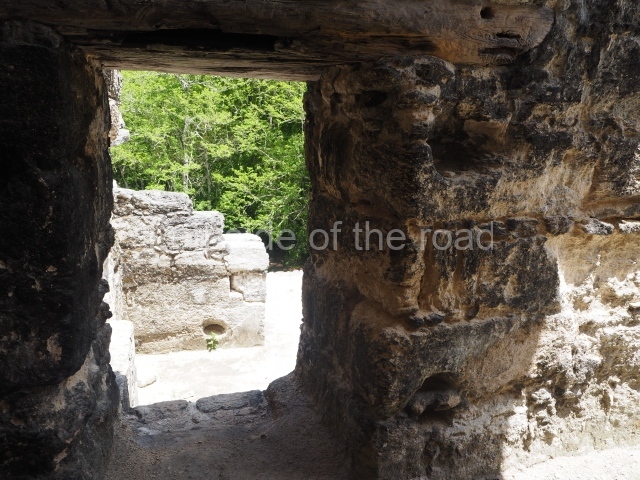

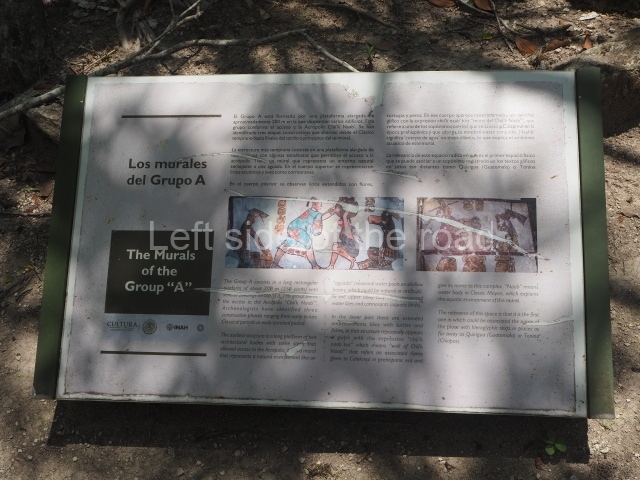

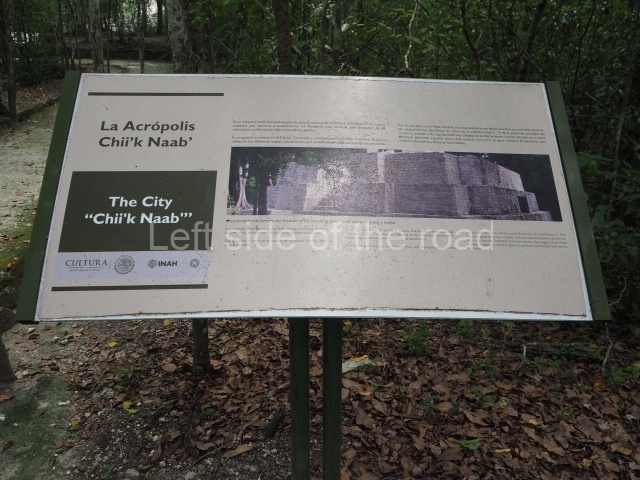

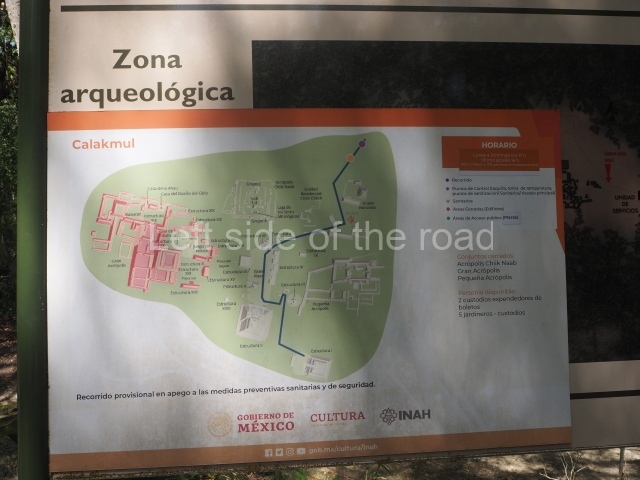

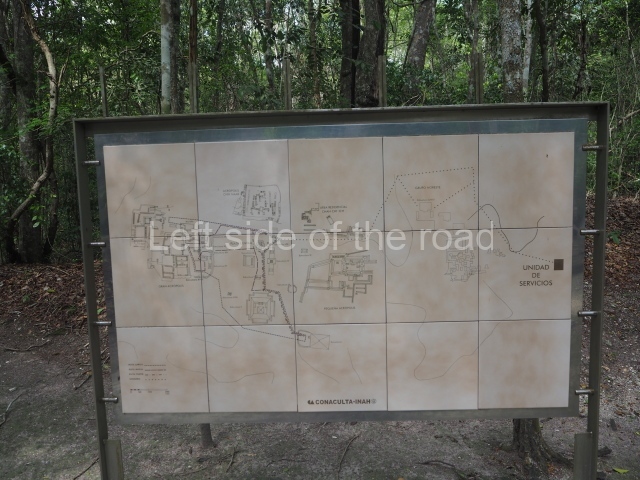

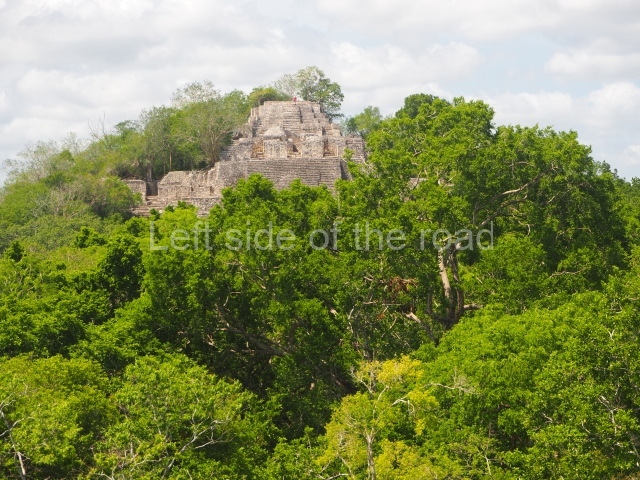

Kabah contains material evidence and works of architecture that clearly demonstrate the degree of complexity, in terms of social organisation, achieved by the Maya in the Puuc region. The most outstanding buildings at the site are the Codz Pop (also known as the Palace of Masks), the plazas of the Palace and the Temple of columns to the east, the Mirador and manos rojas groups to the west, and the Early group, the Great pyramid and its plaza, and the Arch providing access to the monumental area at the centre of the site; all of these display an extraordinary understanding of aesthetics in their architectural design as well as incorporating aspects typical of the different styles in the northern lowlands during the Classic era. Three large groups form the core area at Kabah. The Palace plaza is characteristic of the Puuc architecture developed between the 7th and 10th centuries AD, from the Early Puuc style of the Temple of the sun to the intermediate style visible in the vast Teocalli and finally the Palace, whose classical walls and friezes decorated with colonnettes and tiny drums define it as a prototype of Puuc architecture. But it is the palatial sanctuary of the codz pop that genuinely characterises Kabah. The most outstanding aspects of this building are its facades: the west facade, which has over 250 masks of Chac and is covered with carved, mosaic-like stones from the bottom of the walls to the cornice; and the east facade, nowadays partly restored, whose walls are decorated with extended mats, seven warriors or heroes on the frieze of the three central rooms, and exquisitely sculpted jambstones flanking the main entrance, which display the latest date in the north of the peninsula (AD 987), scenes of a ritual dance and the capture and death of an important figure. Situated some 600 m from the Mirador, the Codz Pop is a monumental single-storey construction with a variable two bays and an architectural plan in the shape of the letter T or IK.

The building measures 54 m on its west facade, 24.5 m in depth and 46 m on its east side. The west wing is composed of two longitudinal bays, each of which contains five rooms. The east wing has just one bay and contains nine rooms; in the north and south wings there are an additional four chambers distributed between three simple bays on each side. The access is either via the south-west corner of the group, which during the latter days of the city’s occupation was sealed by another structure, or via the Teocalli stairways.

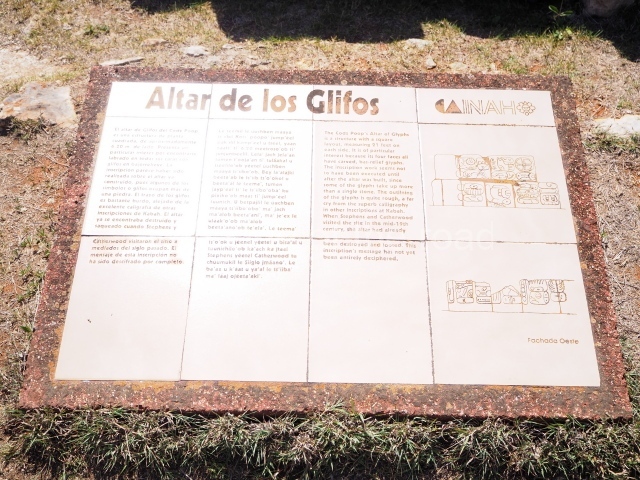

Further west, the Codz Pop platform displays a steep stairway that climbs to the esplanade or plaza where the hieroglyphic altar and chultun are located, the latter opposite the steps leading to the mask facade. George Andrews defines the Codz Pop as belonging to the Mosaic style, based on the west or mask facade, the only one visible when he made his evaluation. Due to both its construction and decorative characteristics, the Codz Pop is a highly unique building and an example of a new variety of the Mosaic style, which implies the development of an autochthonous sculptural form in the Puuc region during the latter years of the Terminal Classic. In terms of their theme, the motifs on the frieze may bear some relation to Temple V or the Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmal: both the conglomeration of Chacs and the sculpted bundle figures are unique elements in this architectural style, which we might call Late Puuc. As the finishing touch to its aesthetics, incomparable with anything else in Maya architecture, the Codz Pop is crowned by a slender tripartite roof comb in which the middle section displays enormous stepped frets; standing over 2 m high, it establishes a dialogue with the roof comb of the Palace in the adjacent plaza. At dawn, the shafts of light filtering through the pilasters and frets of these roof combs are a common sight, cutting through the morning mist beyond the platforms on which these two emblematic constructions stand.

Another notable feature of this site is the hieroglyphic altar in the west plaza of the Codz Pop, which constitutes one of the longest inscriptions in the northern lowlands and whose blocks, currently in disarray, await decipherment to shed further light on the rulers and the history of the site and region. Finally, mention must be made of the chultunes, one in the Palace plaza and the other opposite the mask facade of the Codz Pop; the latter is one of the largest in the Puuc region and to this day it guarantees the supply of water to the site. Situated south of the Codz Pop there is also an aguada or natural depression.

Importance and relations

Kabah, ‘the hand that carves’ or ‘the one below’ (kabal), is distinguished by its strategic location, long occupation sequence and the quality of the carved stones that embellish and lend such great significance to its constructions. At Kabah it is possible to observe an architectural and sculptural development that contains examples of most of the Puuc styles, demonstrating the dynamic evolution of these Yucatec Maya groups. There is also a fringe area with groups of buildings that range from large levelled sections with vaulted structures and spaces such as plazas, to simple platforms with the remains of what must have been dwellings made of perishable materials. Like most Puuc sites, Kabah is a scattered settlement, a layout dictated by the ecological and topographical characteristics of the small valley in which it is situated.

The earliest evidence of the settlement dates back to the Middle Preclassic (600-300 BC), a period about which little is known in this region but which nevertheless laid the foundations for what, towards the Terminal Classic (AD 950-1050), would become Kabah. When you contemplate the ancient city, climb up and down the stairways in front of the palaces, sneak a look inside the endless vaulted rooms with benches, or examine the reliefs on the facades of the constructions, which resemble monumental sculptures rather than buildings, it is easy to imagine the complex daily life of the ancient inhabitants and the process of abstraction they manifested in designing their spaces.

Josep Ligorred i Perramon

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp372-374.

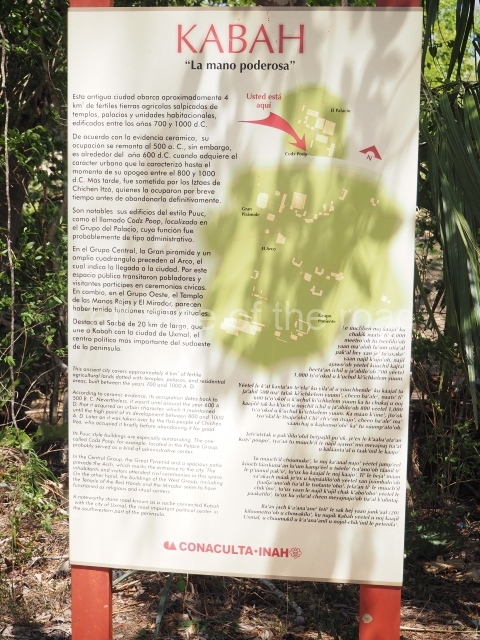

- Palace; 2. Teocalli; 3. Codz Pop; 4. Quadrangle; 5. Great Pyramid; 6. Arch; 7. Sacbe; 8. Early Group; 9. Manos Rojos Group; 10. Mirador Group.

Getting there:

Kabah is located alongside the road that joins Hopelchén and Muna, also passing the major site of Uxmal. Regular buses run along this route but the timings can be crucial if you wish to visit the two sites on the same day. There is a written timetable displayed in the Sur ‘bus station’ in Hopelchén.

GPS:

20d 15′ 13″ N

89d 39′ 19″ W

Entrance:

M$75