Comitan Archaeological Museum

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the former ‘Province of the Plains of Comitan, situated in the eastern half of the state of Chiapas, was inhabited by various human groups dating back to the hunter-gatherers, and the city’s archaeological museum attempts to provide an overview of this development. The Comitan Museum of Archaeology is housed in a former school with an art deco facade, sharing its facilities with the Municipal Public Library. An interior central garden, adorned with a bust of the local musician Esteban Alfonso, is surrounded by corridors and three rooms.

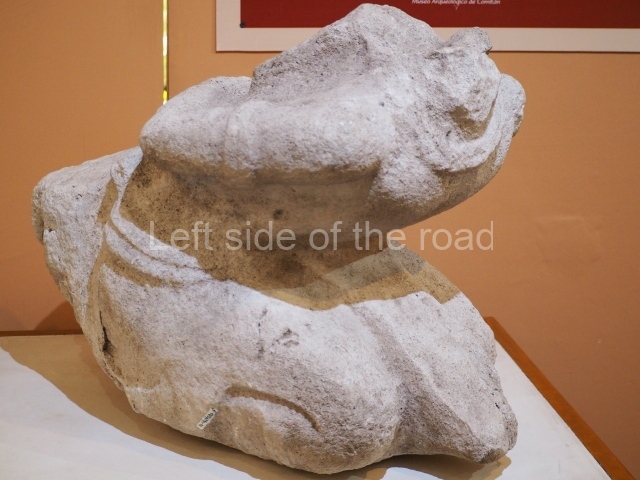

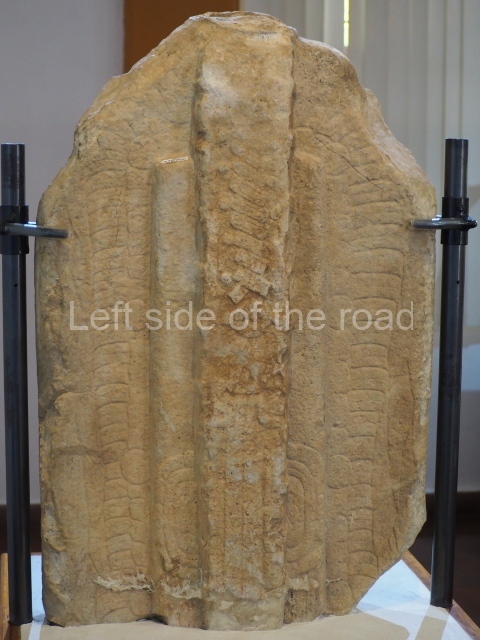

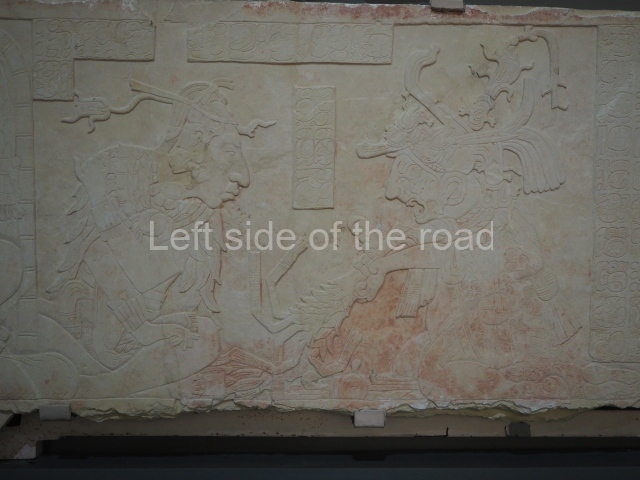

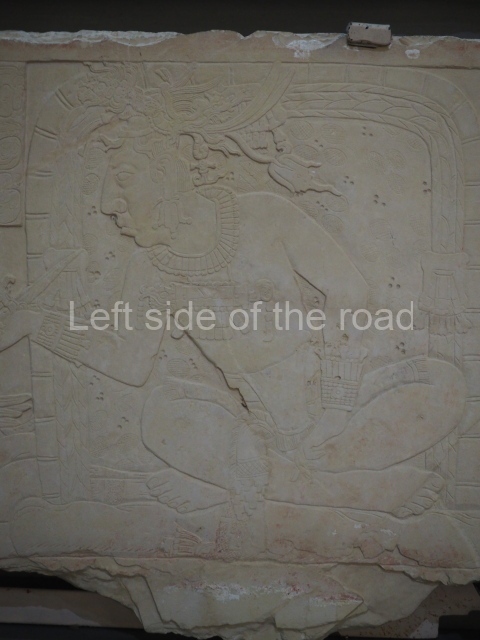

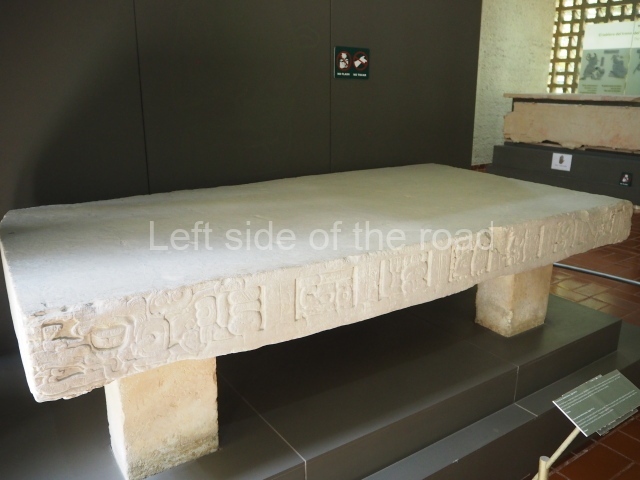

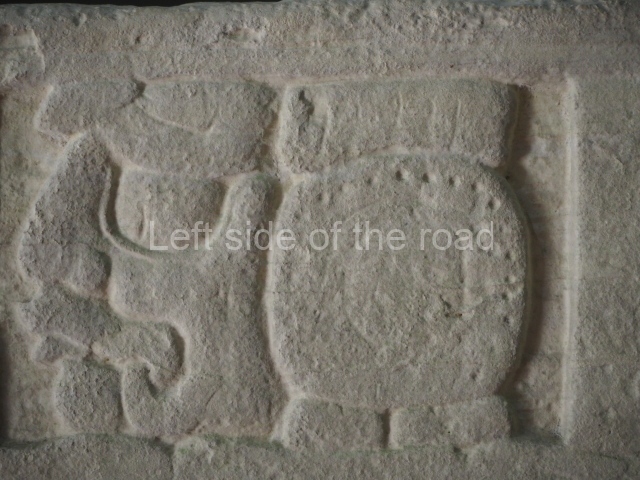

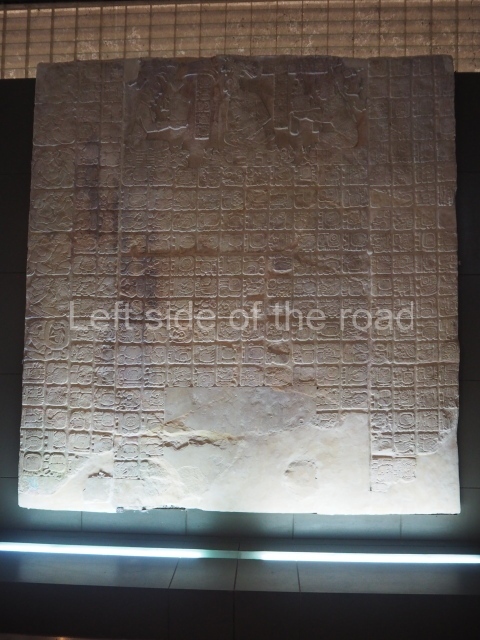

The first room charts the cultural development of the eastern Chiapas Highlands. It begins with a simple outline of the evidence of groups of hunter-gatherers who lived in the Teopisca, Aguacatenango and Amatenango areas of the valley around 8,000 BC. The next section is devoted to the preclassic era, when the first sedentary communities were established, mainly in camps near streams and rivers with simple mud huts and the incipient use of masonry. The vessels and pieces of figurines on display were found at the archaeological site of La Libertad. One of the most important exhibits from this period is the Altar of Sivalnajab, which depicts a reclining dignitary and a pair of stepped mouldings; two flowers adorn the corners of the altar, while the sides display aquatic patterns. According to the archaeologist Carlos Navarrete, the associated elements suggest that this dignitary represents an act of ritual masturbation related to fertility. The flower carvings on this altar were chosen as the museum’s symbol.

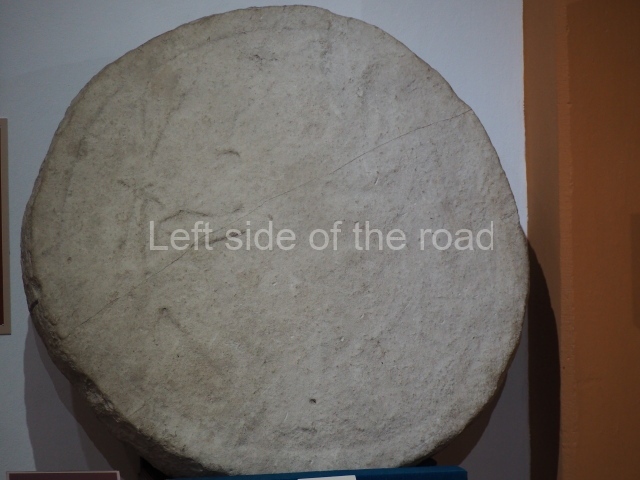

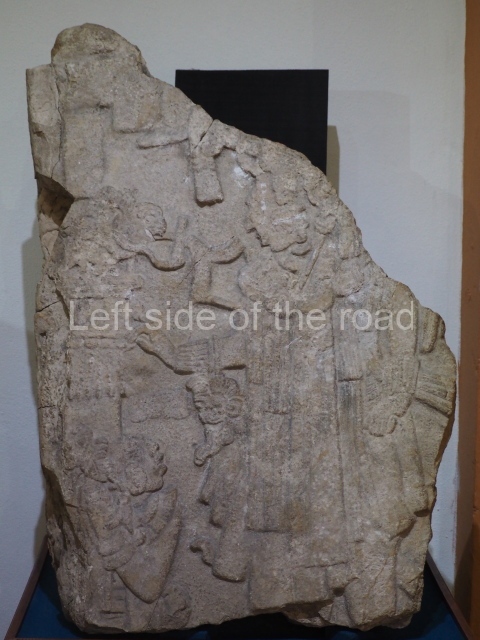

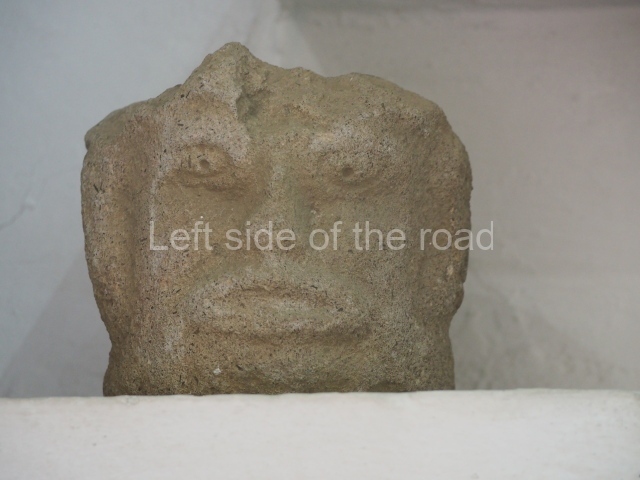

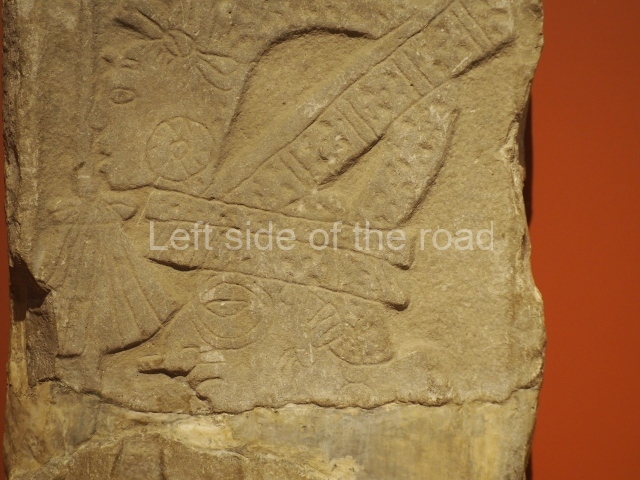

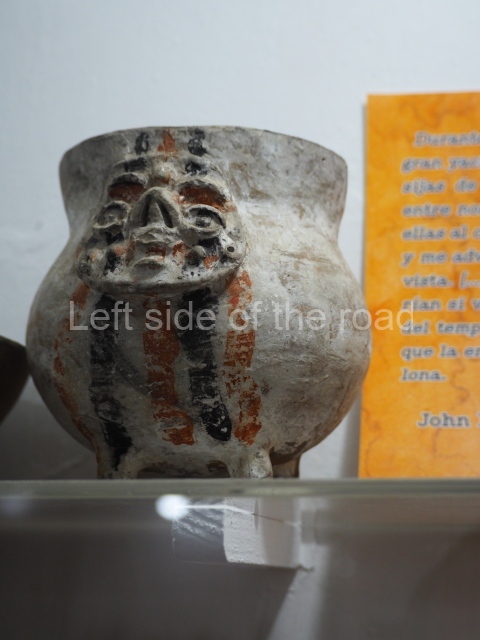

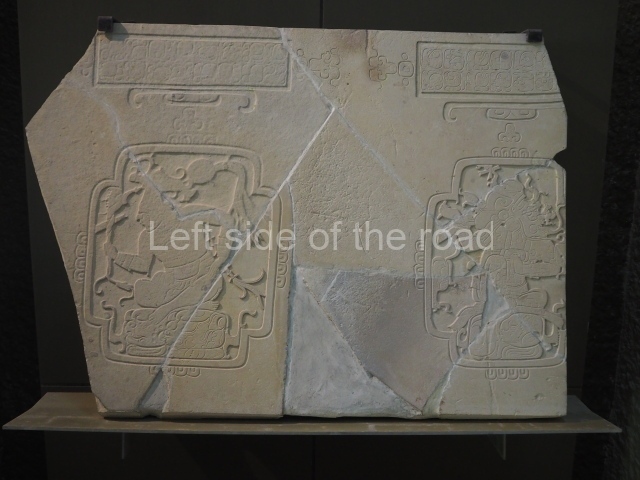

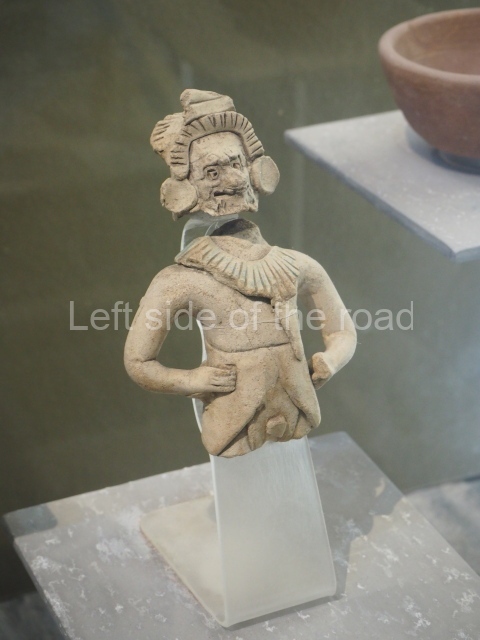

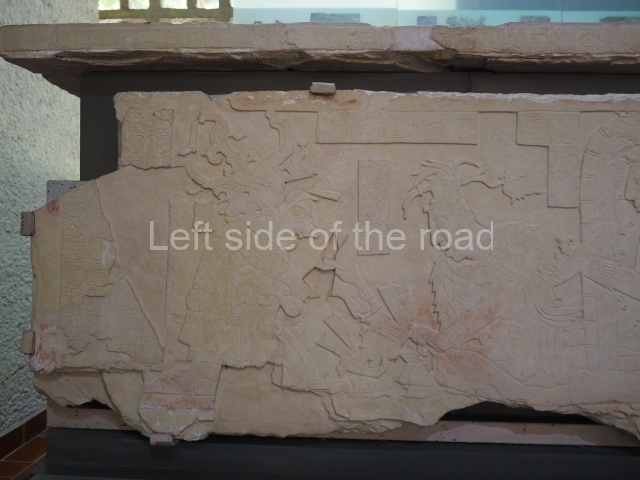

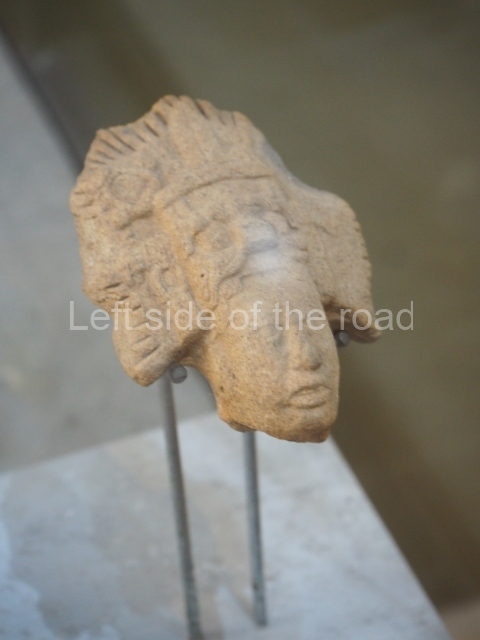

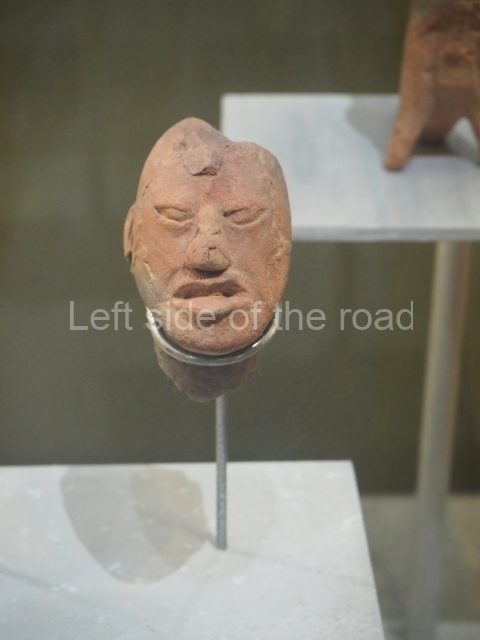

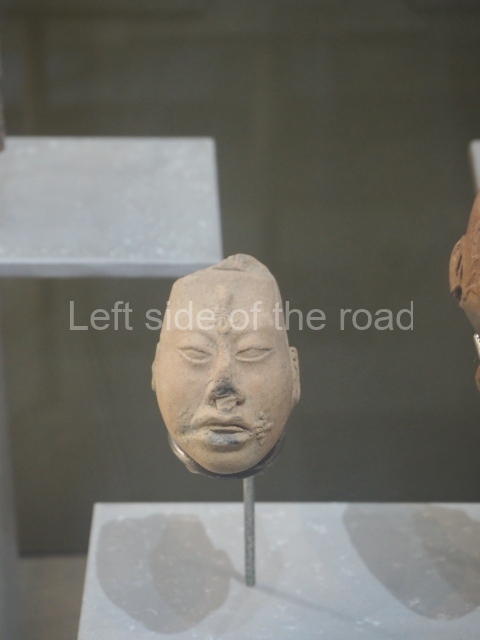

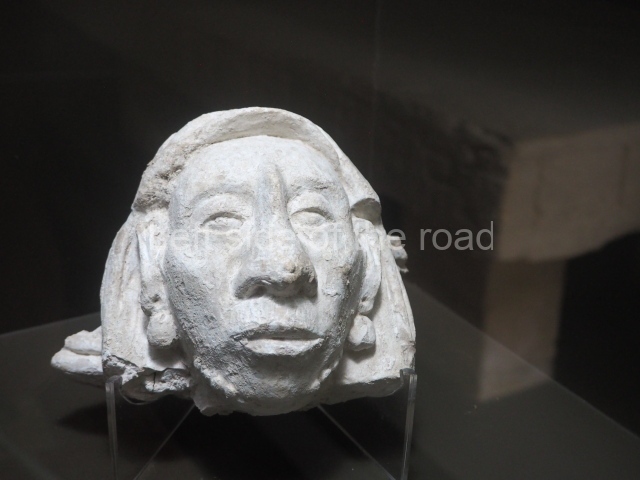

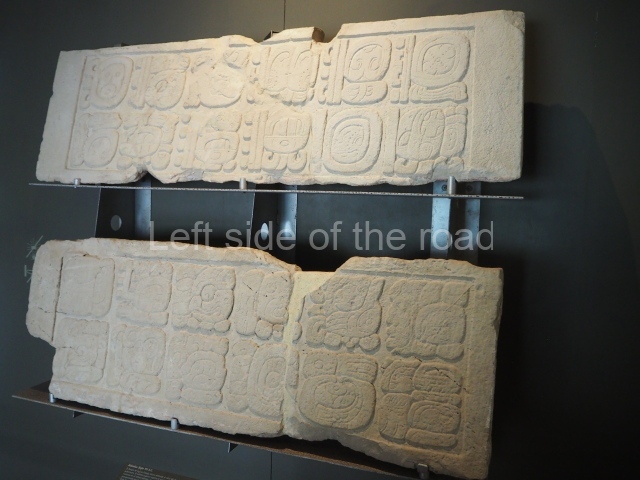

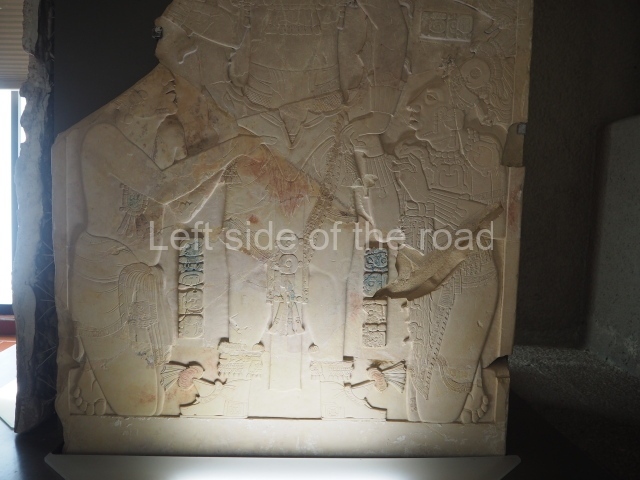

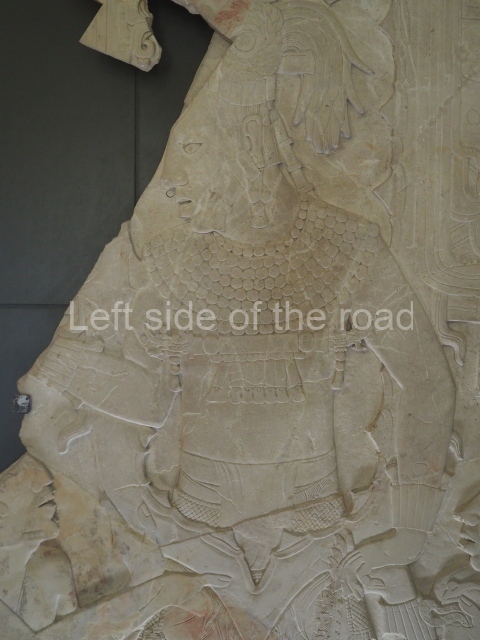

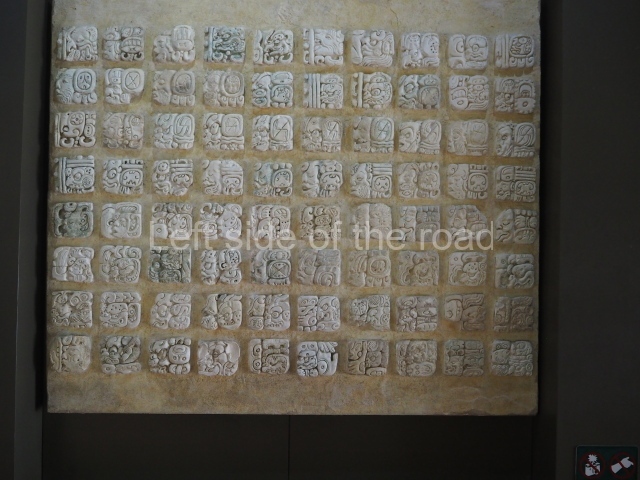

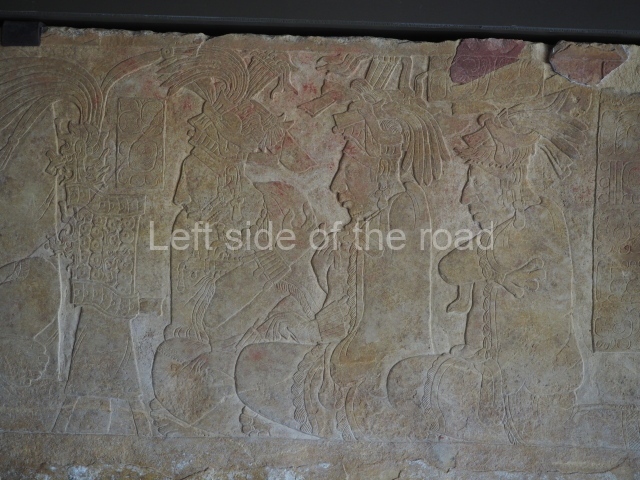

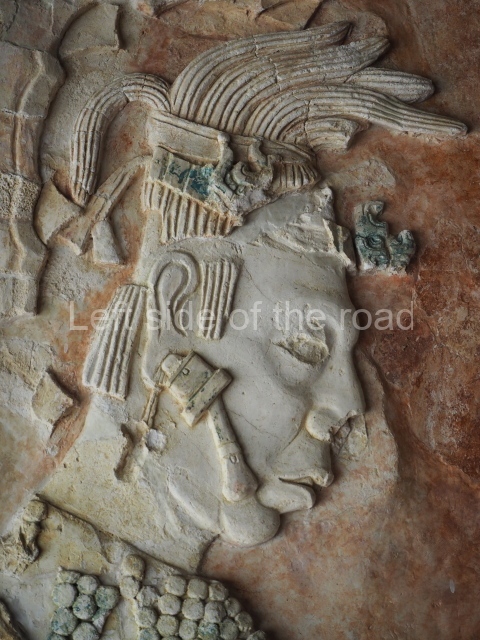

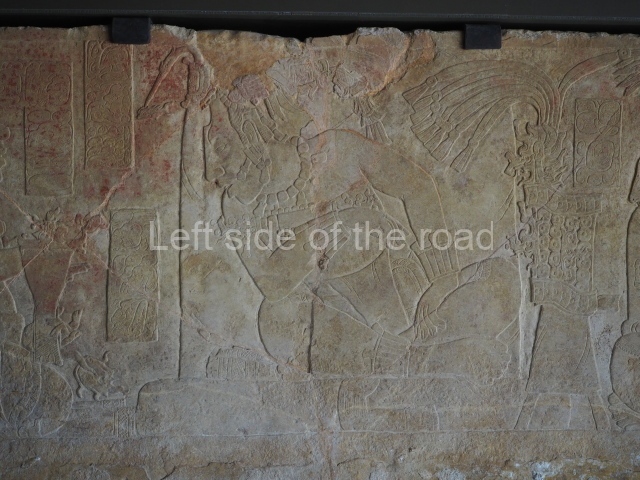

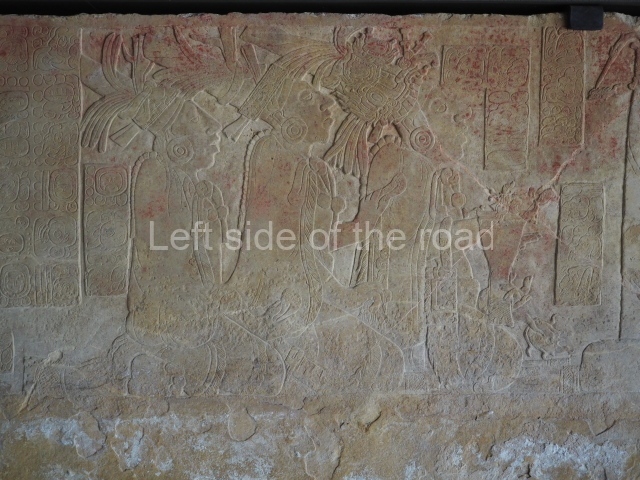

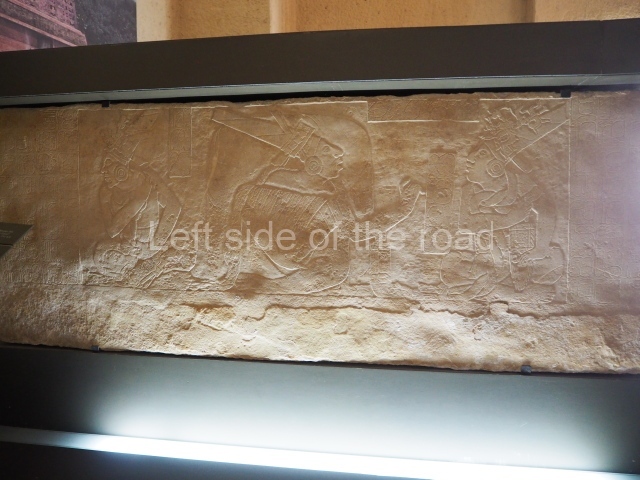

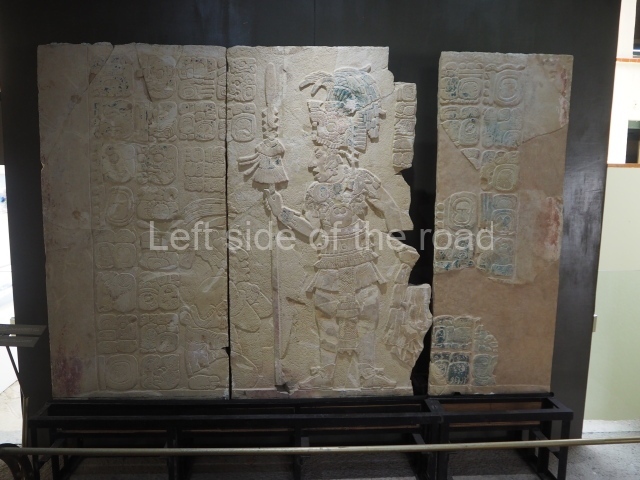

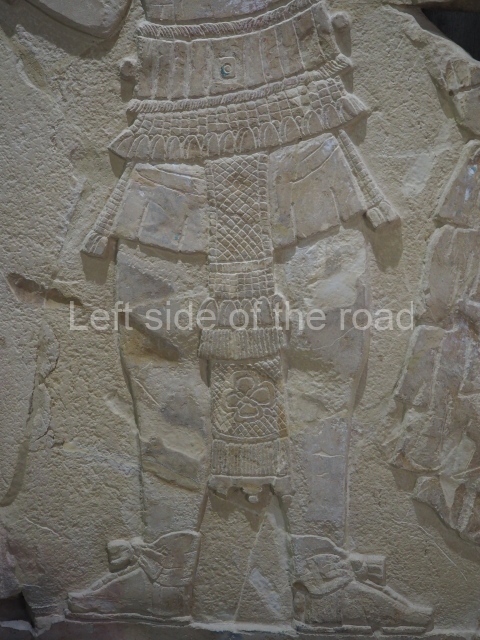

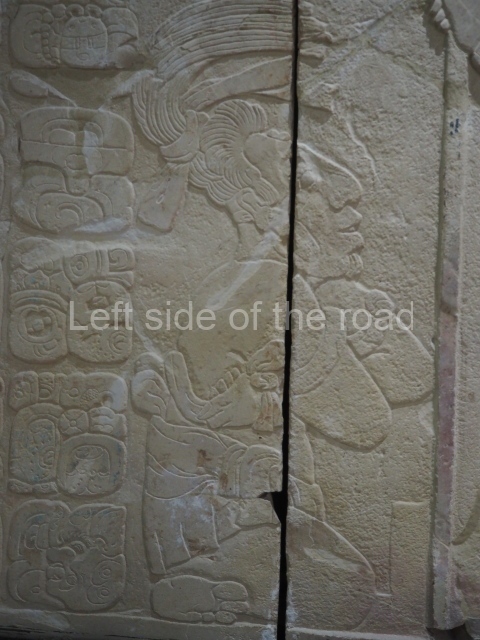

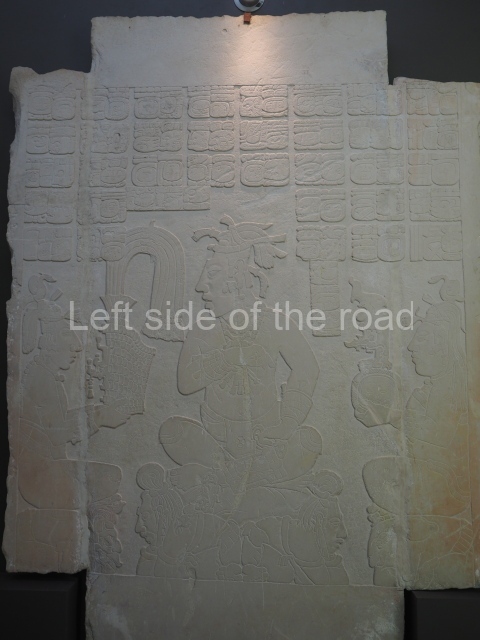

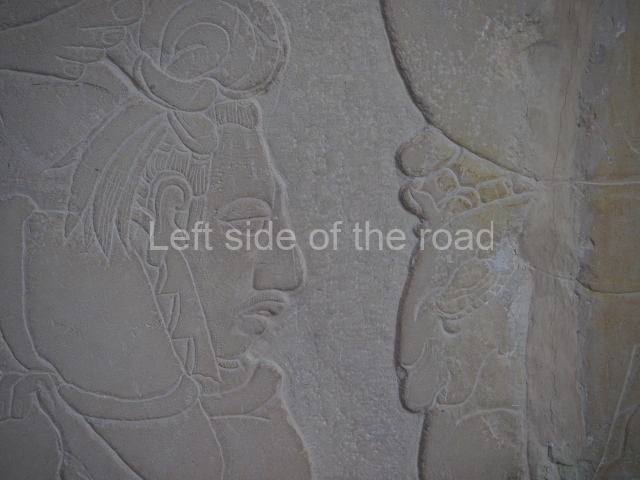

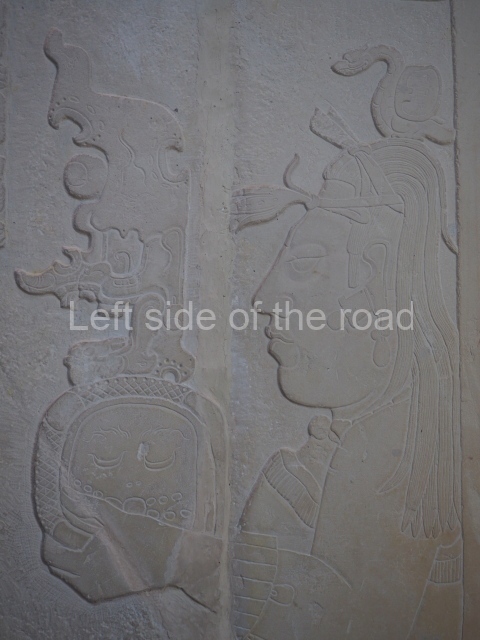

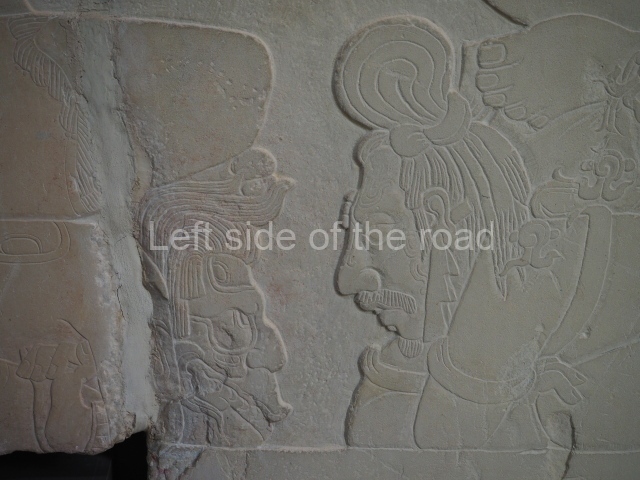

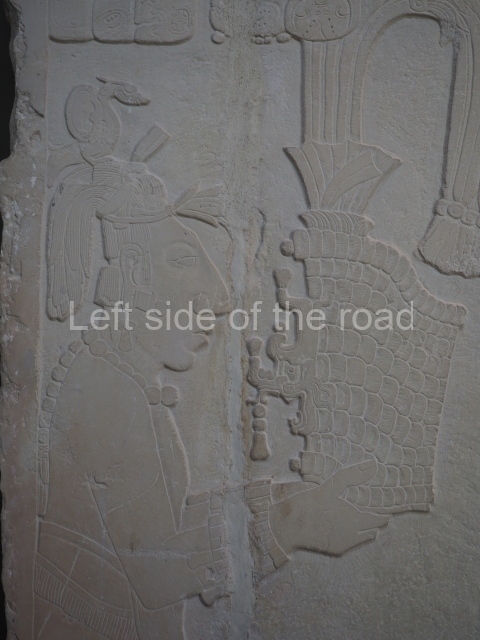

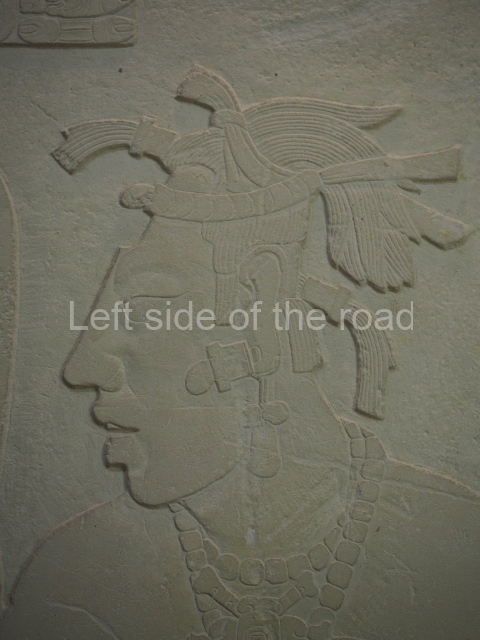

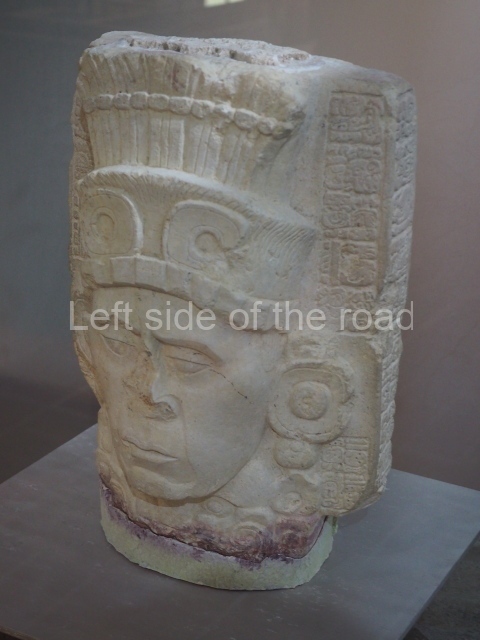

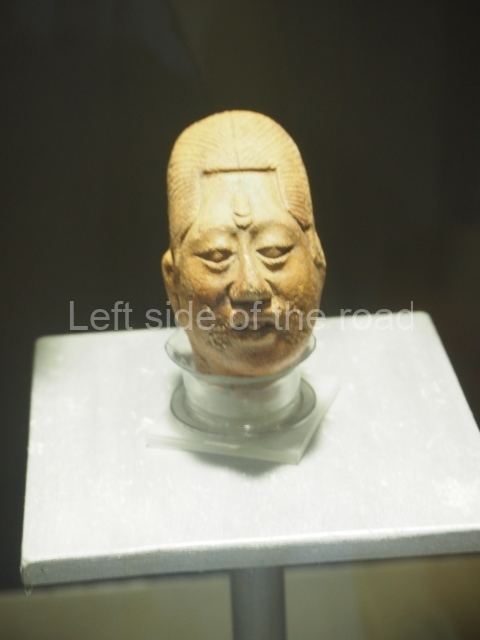

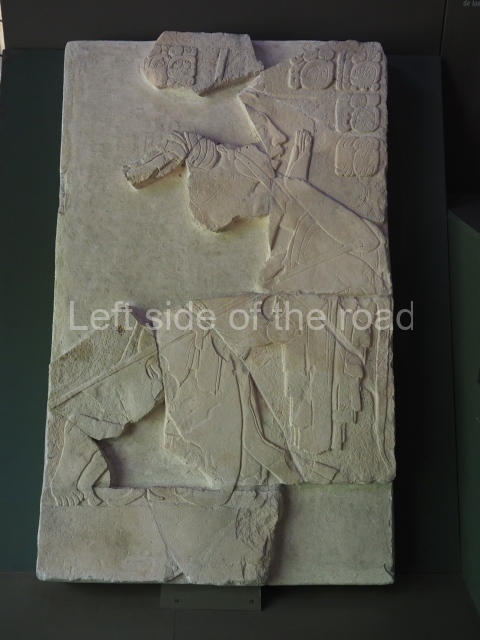

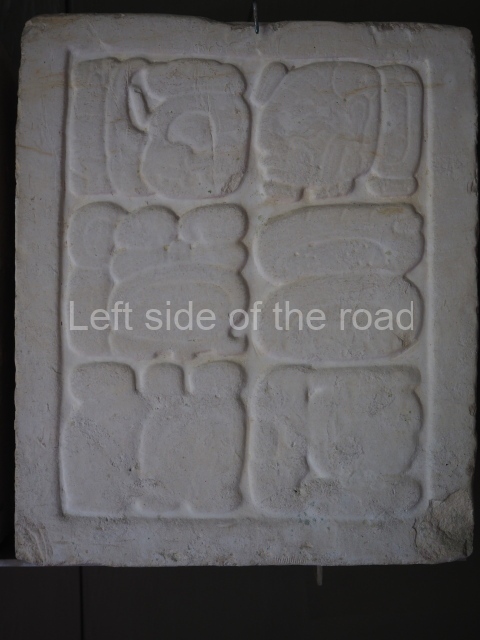

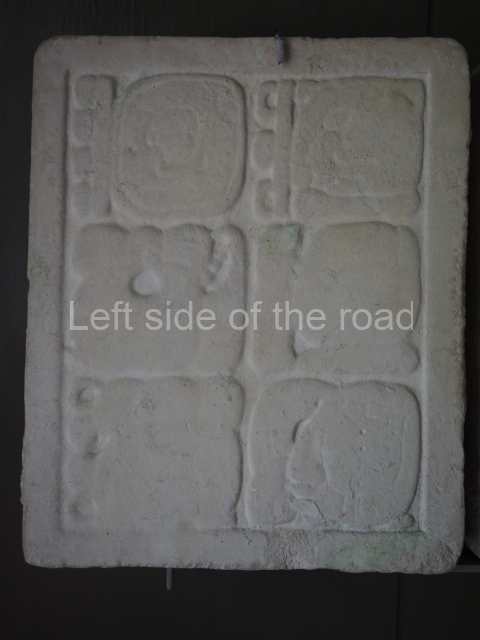

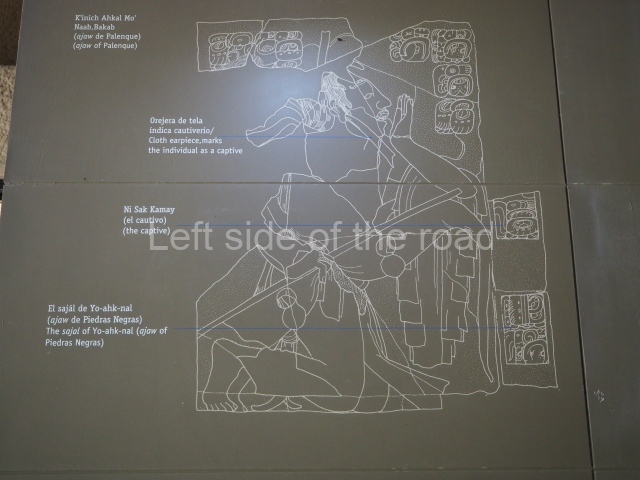

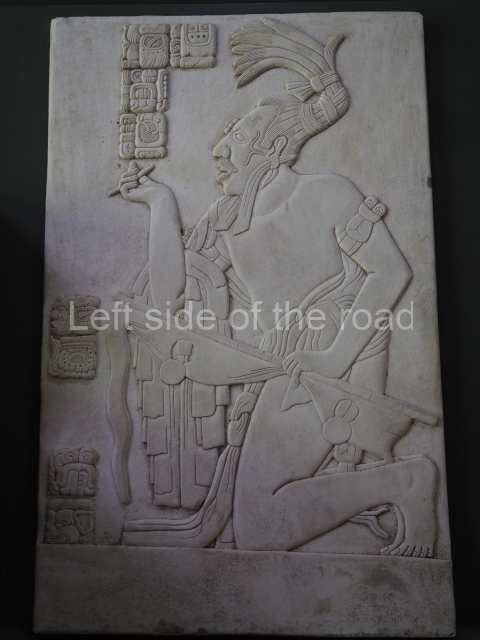

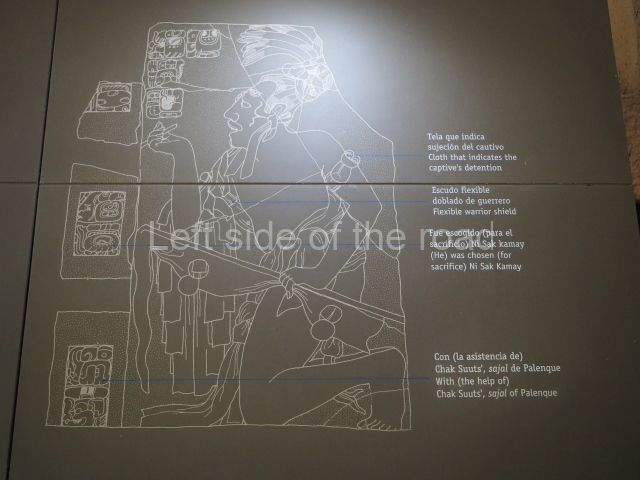

The following section is given over to the c la ssic era, the golden age of the Maya culture. Numerous sites established their principal constructions on mountaintops, with ball courts in the most important cities. This section contains several sculpted stelae, such as Monument 18 from Chinkultic which shows the principal figure standing and a seated figure opposite him, staring at the object hanging from the first dignitary’s hand. Also on display are various ornaments from Yerbabuena, including a small pyrite mirror. Tenam Rosario is represented by numerous circular ball court markers showing scenes of warriors with eye pieces, reminiscent of Tlaloc (the rain god on the central plateau), as well as images of moon gods. The figurines from Lagartero occupy a prominent place in the display and provide visitors with an extraordinarily realistic impression of the headdresses and clothing worn by the elite classes.

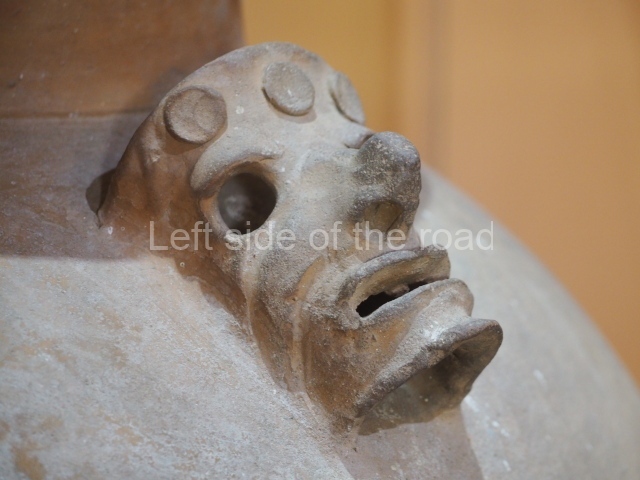

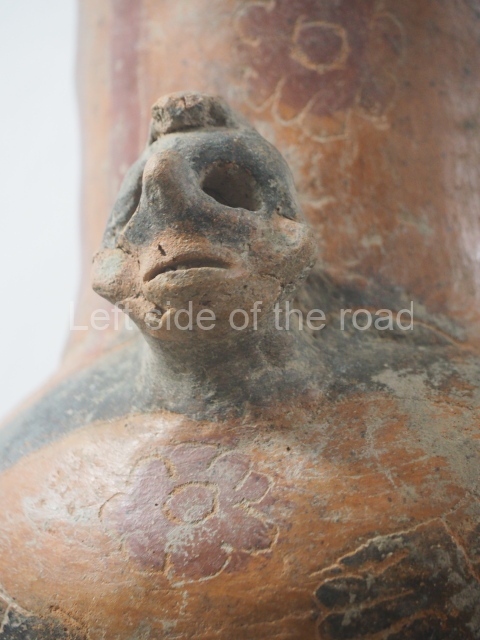

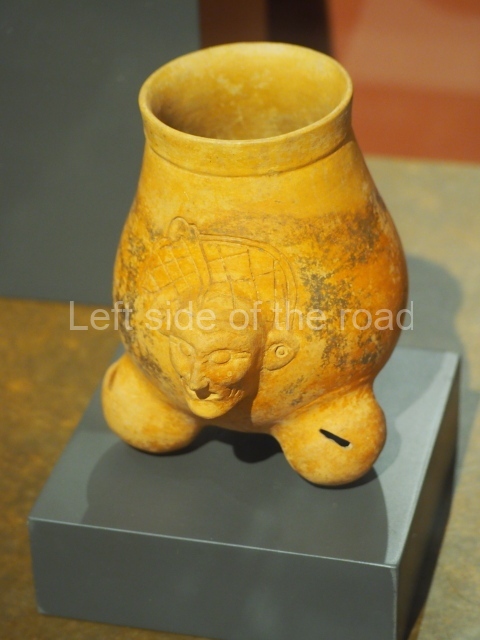

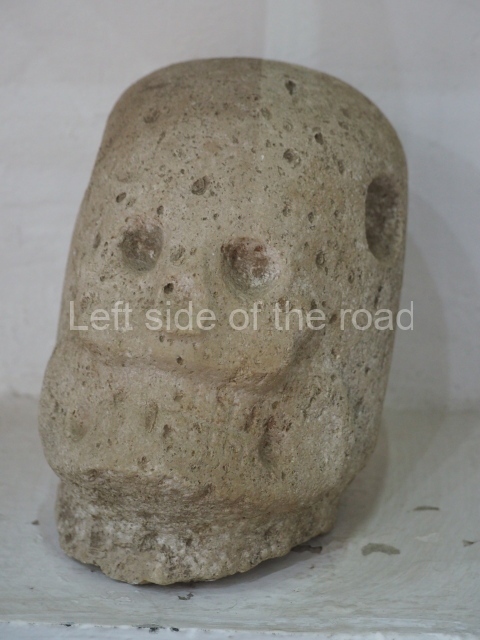

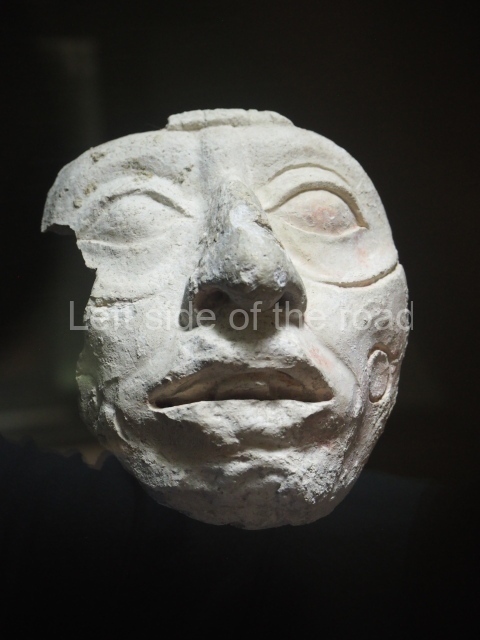

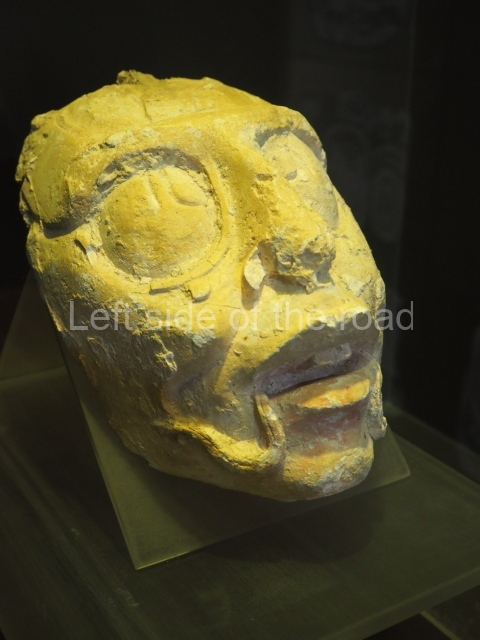

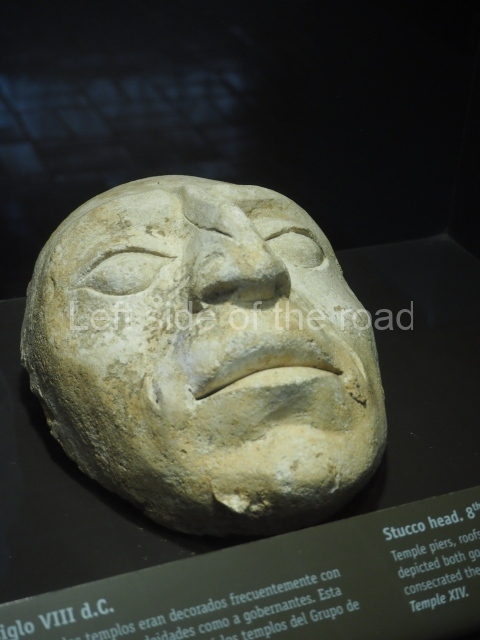

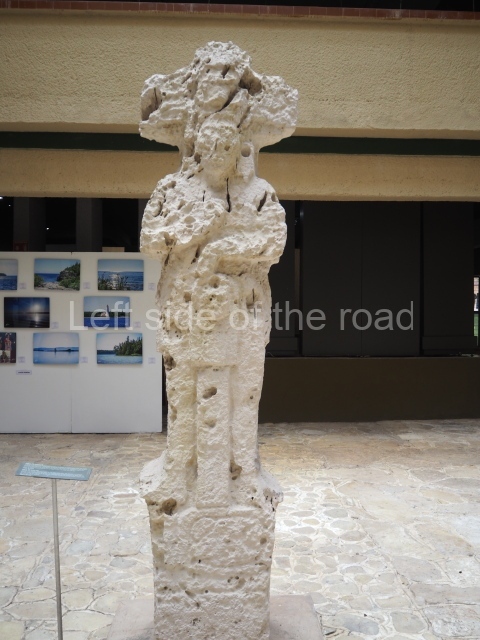

Caves are very common in this region and the ancient Maya regarded them as sacred natural elements. An example of this can be seen in the reproduction of the and a so lo s cave (the popular name for the badger), the first exhibit when the museum was created. The objects have been placed exactly as they were found during the exploration of the original cave. A large ceremonial urn is decorated with dignitaries and symbolic elements of the Maya underworld, as well as elements related to the sun, serpents, bats and quetzals. There are also vessels with effigies of batmen and pieces such as the ceramic box with a lid that depicts personages wearing funerary masks. The exhibits are completed by various vessels and masks made from limestone.

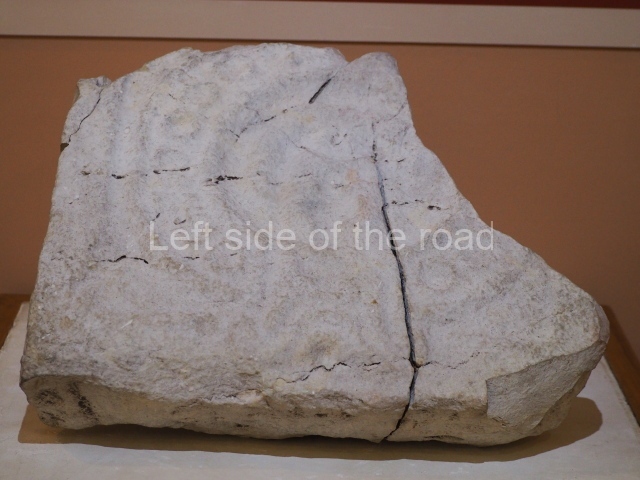

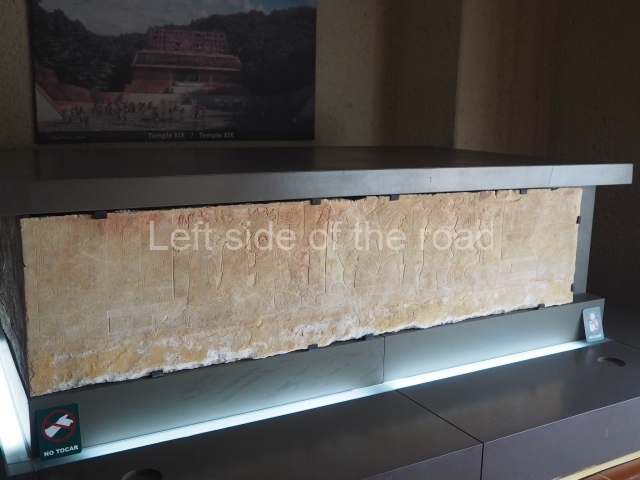

In the transition towards the Postclassic era, the Maya groups abandoned the mountain settlements and moved down in to the valley, mainly to the Las Margaritas area. The ceramics from this era are known as Plumbate (due to their finish and metallic sound), and the main production centre was located in the distant Soconusco. Metallurgy also emerged during this period, as evidenced by the pieces found at Guajilar, in the upper tributaries of the River Grijalva. The second room is used for temporary exhibitions but also contains a space reserved for the collection from some of the caves in the region. The final room is given over to the findings from Tenam Puente. The objects on display illustrate this site’s trading links with regions on the Gulf coast, as evidenced by the Fine Orange ceramics, and with Soconusco, manifested in the Plumbate pottery. Other materials such as alabaster were placed as offerings at human burial sites, as were conches and sea shells. The sculptural elements contain a piece of headdress very like the ones worn by the dignitaries at Tonina, as well as a few fragments of prisoners with their hands tied behind their backs. Meanwhile, the reproduction of Tomb 10 documents the extreme care and devotion with which the most important people were buried, accompanied by a large urn and rich grave goods.

Gabriel Lalo Jacinto

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, p479.

Location;

1 Calle Sur Oriente, just off the main square in the historical centre, the same block as the church.

Entrance;

Free