Worker and Kolkhoz Woman

Worker and Kolkhoz Woman (Russian: Рабочий и колхозница) is a sculpture of two figures with a hammer and a sickle raised over their heads. The concept and compositional design belong to the architect Boris Iofan. It is 24.5 metres (78 feet) high, made from stainless steel by Vera Mukhina for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris and subsequently moved to Moscow. The sculpture is an example of socialist realism in an Art Deco aesthetic. The worker holds aloft a hammer and the kolkhoz woman a sickle to form the hammer and sickle symbol.

The sculpture was originally created to crown the Soviet pavilion of the 1937 World’s Fair. The organisers had placed the Soviet and German pavilions facing each other across the main pedestrian boulevard at the Trocadéro on the north bank of the Seine.

Mukhina was inspired by her study of the classical Harmodius and Aristogeiton, the Winged Victory of Samothrace and La Marseillaise, François Rude’s sculptural group for the Arc de Triomphe, to bring a monumental composition of socialist realist confidence to the heart of Paris. The symbolism of the two figures striding from West to East, as determined by the layout of the pavilion, was also not lost on the spectators.

Mukhina said that her sculpture was intended ‘to continue the idea inherent in the building and this sculpture was to be an inseparable part of the whole structure but after the fair, the Rabochiy i Kolkhoznitsa was relocated to Moscow where it was placed just outside the All-Russia Exhibition Centre.

In 1941, the sculpture earned Mukhina one of the initial batch of Stalin Prizes.

The sculpture was removed for restoration in autumn of 2003 during the city’s Expo 2010 bid. The plan was that the sculpture could be back at its place by 2005, but this did not happen after the city lost the bidding process to Shanghai and many financial problems contributed to a delayed re-installation.

At the end of 2009 the monument returned to its place at VDNKh after 6 years of restorations. The revealing of the restored monument was held on the evening of December 4, 2009, accompanied by fireworks and a light show. The restored statue uses a new pavilion as pedestal, increasing its total height from 34.5 metres (the old pedestal was 10 metres tall) to 60 metres (the new pavilion is 34.5 metres tall plus the 24.5 metres of the statue itself).

The main structure of the monument was made at The Moscow factory of aggregate machine tools and automatic lines (called ‘Stankoagregat’) while the smaller components of the outer covering were created at the pilot plant of the Central Research Institute of Mechanical Engineering and Metalworking, overseen by Professor Pyotr Nikolayevich Lvov. He suggested using stainless chrome-nickel steel for the sculpture, despite initial doubts from Vera Mukhina and the rest of the team. The main reason steel was chosen over bronze and copper was because it had a better ability to reflect light. The goal was for the monument to shine brighter than the eagle on the German pavilion and the Eiffel Tower. Lvov invented resistance spot welding, a technique that was used to skin airplanes since the 1930s. Instead of using the traditional riveting method, the decision was made to use this technology for assembling the sculpture.

At the start of the project, the workers had four plaster models to use, with the tallest one being 95 cm. They assembled the monument in the factory courtyard using a crane that was 35 meters high with a 15-meter boom. The templates for the plating parts were made of wood, and the carpenters used 15 cm thick boards. The moulded parts were then shaped from inside the monument. People involved in the project remembered these details:

‘Working in February was particularly challenging due to the cold weather and strong winds. The only respite from the wind was inside the frame or ‘under the skirt of the Kolkhoznitsa’. To keep warm, we relied on a fire that was built in a cauldron dug into the ground. Additionally, we had to manually weld the sheathing sheets’.

A different approach was needed to create the hands and heads of the sculpture. Instead of using wooden templates, clay was used to fill in the damaged wooden blanks for the heads, which were then molded with steel. The creation of the scarf posed challenges, as it was a large and heavy piece that needed to be supported without external help. During the creation of this artwork, factory director S. P. Tambovtsev criticized Mukhina for causing delays with numerous revisions and claimed that the scarf she had designed could potentially damage the sculpture during windy weather. However, his complaints were ignored, and engineers B.A. Dzerzhkovich and A.A. Prikhozhan managed to create a truss to support the scarf, allowing it to appear as if it was floating behind two figures.

During this time period, the sculpture was created and it was supported by a heavy frame weighing 63 tons. The outer shells of the sculpture, made from thin sheets of 0.5 mm steel, only weighed 12 tons. The entire process took three and a half months. Once the sculpture was assembled, it was visited by a government commission led by Kliment Voroshilov, the People’s Commissar of Defence. Later that evening, Joseph Stalin, the leader of the USSR, inspected the finished monument. Shortly after, the sculpture was dismantled for transportation to Paris.

In 2003, plans were made to restore the monument, and it was supposed to be finished by 2005. The Moscow government provided a budget of 35 million roubles for the dismantling process, including 5 million US dollars for scaffolding to meet safety regulations. However, the project was put on hold due to suspected embezzlement, and it was not resumed until 2007 after several inspections.

On December 31, 2008, the government announced a new tender for the restoration with a maximum contract amount of 2.395 billion roubles. The only company to participate and win the tender that same day was SK Strategia, a subsidiary of Inteko owned by Yelena Baturina, the wife of former Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov. The contract amount was increased to 2.905 billion roubles. Finally, the restoration was completed in November 2009.

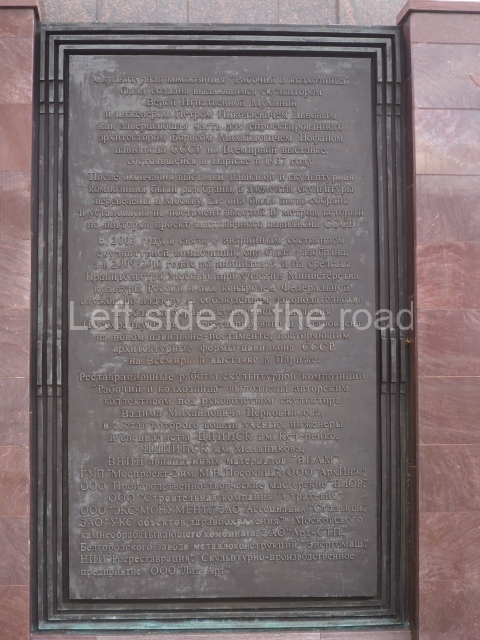

The sculpture project was led by Vadim Tserkovnikov and the materials were made by the Vladimir Kucherenko Central Research Institute of Steel Structures. The casting and installation were done at the Energomash plant in Belgorod. The Melnikov Central Research Institute of Steel Structures worked on new calculations and designs for the frame, as the original documentation was not available and the new materials have different properties. The employees at the All-Russian Institute Of Aviation Materials (VIAM), under the leadership of E.N. Kablov, developed coatings and materials that are highly resistant to corrosion in order to restore the sculpture.

The sculpture was taken apart into 40 pieces and each piece was photographed to assess the level of damage caused by corrosion. Only 10% of the pieces needed to be replaced completely, while the rest could be restored. Additionally, the welding points were examined through radiography, with over one million points being checked. The sculpture had design flaws that made it not airtight, resulting in moisture build up and pigeons nesting inside.

The second step in the reconstruction process involved cleaning the sculpture. The contaminants, particularly in the scarf and skirt areas, had accumulated over 70 years and resembled stalactites. Technobior developed a highly toxic and fluid substance to dissolve these contaminants and fully clean the surface. VIAM created an anti-corrosion paste specifically for the restoration of this sculpture, which won an award at an international exhibition. This paste can be applied at any angle, prevents spreading, enhances adhesion, and increases resistance to environmental damage. A ton of paste was used to treat the sculpture parts, and an additional protective compound was applied on top.

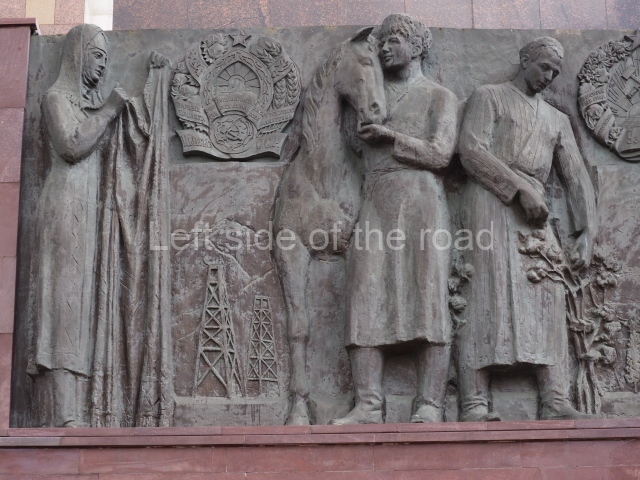

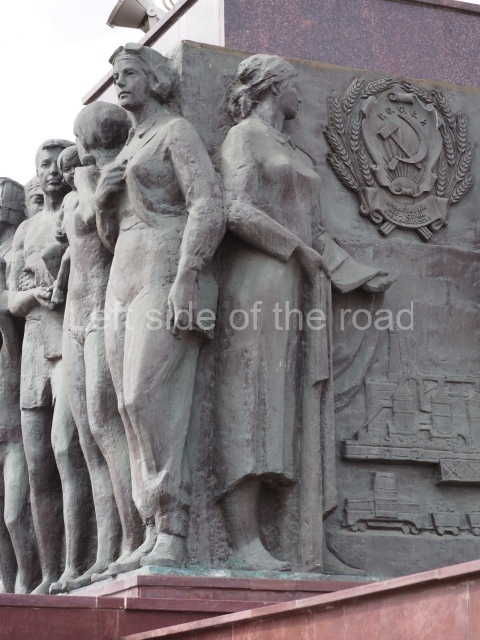

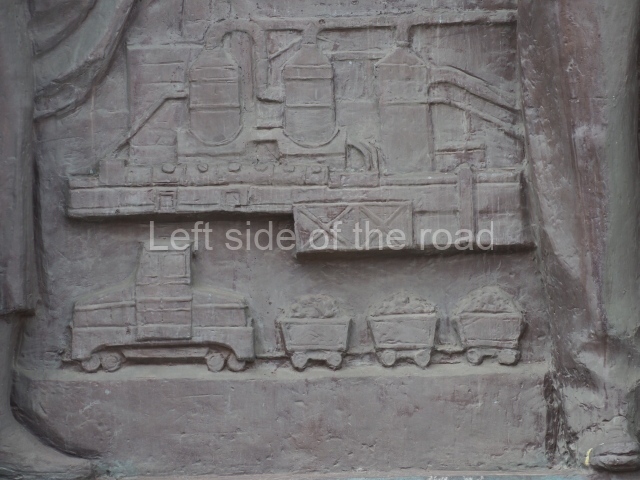

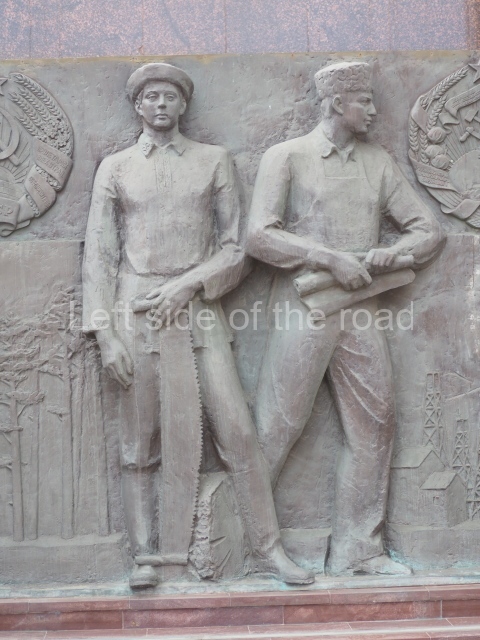

Under Tserkovnikov’s guidance, a new triple frame was calculated and designed for the monument. This frame is divided into a load-bearing frame, an intermediate frame, and a structural frame that connects the shell and load-bearing frame. As a result of the reconstruction, the weight of the support increased by 2.5 times to account for the load of hurricane wind. The total weight of the monument now stands at 200 tons. The sculpture was placed on the pavilion, following the general design of Iofan’s original project from 1937. The length of the building is 66 meters, and the original coat of arms created for the exhibition in 1937 is installed on the façade.

The monument was installed on November 28, 2009, using a specialized crane from Finland, of which there are only three in existence. The official unveiling of the monument occurred on December 4, 2009.

The total cost of dismantling, storing, and restoring the sculpture was 2.9 billion roubles. However, experts believe that this amount is at least twice as high as it should be. Vadim Tserkovnikov mentioned in an interview that the actual restoration expenses were much lower compared to the additional costs, such as constructing a 60-meter high scaffolding and hiring a crane from Finland, which cost several tens of millions of roubles.

In Soviet cinema, the sculpture was chosen in 1947 to serve as the logo for the film studio Mosfilm. It can be seen in the opening credits of the film Red Heat, as well as many of the Russian films released by the Mosfilm studio itself.

A giant moving reproduction of the statue was featured in the opening ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, symbolizing post-World War II Soviet society, particularly in Moscow.

Text above from Wikipedia.

The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman (meaning a worker on a collective or State farm) is one of the most iconic representations of Soviet Socialist Realism sculpture. And it played an ‘active’ role in the battle against the extreme manifestation of capitalism, the fascism of Nazi Germany which was nurtured and promoted by the so-called western ‘democracies’. In 1937 when fascism was rampant in various capitalist countries – and whilst the Spanish Civil War was raging on the Iberian Peninsular – the statue stood opposite the Nazi swastika and eagle in the area in front of the Eiffel Tower during the World’s Fair of that year. Two social systems confronted each other in a benign manner in 1937 but it was only one of them who would come out victorious in the real conflict which was the Battle of Stalingrad of 1942/43.

In its imagery it encompassed much of what the Soviet Union, in the construction of Socialism, was aiming to achieve; equality between men and women; both on an equal footing in the construction of a new society; the unity of the industrial worker and the worker on the land; marching determinedly forward to a new future, devoid of exploitation and oppression; a future free of militarism; a future where labour was respected as being the creator of all wealth and where those who created that wealth were able to enjoy the fruits of their labour without it being stolen by a parasitic and avaricious capitalist class; and the choice of stainless steel in its construction being able to outshine anything that fascism or capitalism could produce.

I had seen pictures the sculpture and had also seen scaled models in various museums before going to the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, VDNKh, but nothing really prepared me for the sheer size of the sculpture in real life. Even standing on the pedestal of the reconstructed building from the 1937 World’s Fair it looked immense.

And the efforts to return it to its former glory, although taking many years (due to political and economic reasons) and costing possibly more than it should have (due to funds going to those not deserving) the results are truly impressive.

The Sculptor

Vera Mukhina (1889-1953)

Vera Mukhina was a teacher and artist working in easel, monumental, monumental-decorative and memorial sculpture, in theatrical design and applied art. She also wrote articles on contemporary art and sculpture. She studied at the private art schools of Konstantin Yuon (1909-11), Nina Sinitsina (1911) and Ilya Mashkov (1911-12) in Moscow, and at private establishments in Paris (the Academies Colarossi, de La Palette and de la Grande Chaurniere, 1912-14). Lessons from Antoine Bourdelle were especially important for Mukhina’s development as an artist. She was also influenced by Cubism, which was particularly noticeable in her early drawings. In the 1920s she played an active part in the implementation of the plan for Monumental Propaganda. Her best efforts in that field were a design for The Flame of the Revolution (1922-23) and a monument to the Revolution for the town of Klin (1919). From 1926-30 she taught at the VKhUTEIN (Higher State Art and Technical Institute) in Moscow. The chief result of her tireless search for a synthesis of monumental sculpture and architecture was Worker and Kolkhoz Woman for the Soviet pavilion at the Paris Exposition of 1937. With this work she won world fame and became arguably the most popular symbol of the Soviet state. Among her designs for monuments that were executed are those to Maxim Gorky (1952) and Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1954), both in Moscow. In the 1930s-40s she produced an extensive gallery of portraits of contemporaries, as well as a large number of designs for monuments and monumental-decorative sculptures that never came to fruition. Mukhina contributed to the revival of the production of artistic glass. Through her efforts a glass factory was established in Leningrad in the late 1930s that went on to become one of the foremost in the country.

From Soviet Women and their Art, Rena Lavery and Ivan Lindsay, Unicorn, London, 2019.

Location;

Now on a reconstructed building of the original at the 1937 Paris Exhibition which is just outside the main VDNKh exhibition area in Moscow.

How to get there;

The site is served by the VDNKh metro station, on Line 6, the brown one.