People’s Palace

People’s Palace – Bucharest

Shortly after the earthquake in 1977, the Romanian communist leader of the time, Nicolae Ceauşescu, initiated the plan to build a new political-administrative centre in Bucharest, in the area of the Uranus hill, the higher part of the Dâmboviţa hill, area which was confirmed by specialists as being safe for the construction of monumental buildings. This plan started as a consequence of the urbanization campaign and it was influenced by the friendship with the North Korean leader at that time, Kim Ir Sen (Kim Il Sung).

Starting in 1980, 5% of the Bucharest area was demolished. This was the end of Uranus neighbourhood, the end of those small streets paved with cubic stone, with old and quaint Romanian houses with bohemian glamour, many of which brought to light by architects from that time. 20 churches were destroyed, 8 were moved, 10,000 homes were demolished, and over 57,000 families were evicted. Brâncovenesc Hospital which was the first forensic medicine institute in the world was demolished, also.

But this was only the beginning: People’s House, the current Palace of Parliament, took almost 10 years of hard work that brought together over 100,000 workers, more than 20,000 persons working 24 hours three shifts per day. Between 1984 and 1990, 12,000 soldiers took part in the construction works, as well.

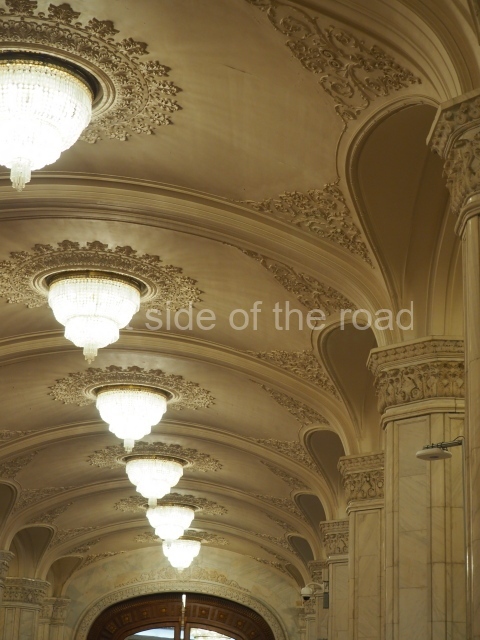

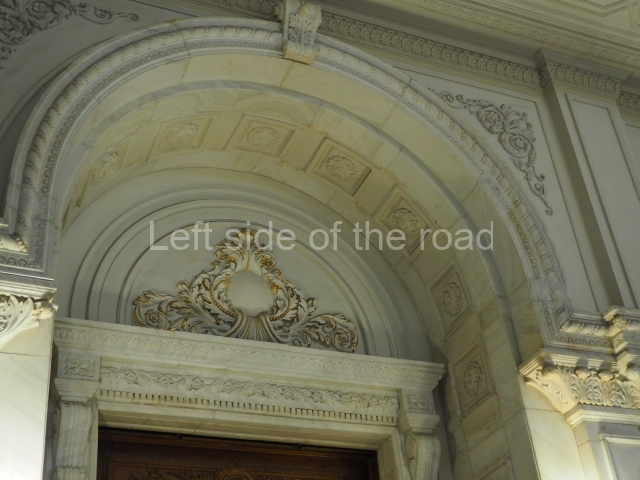

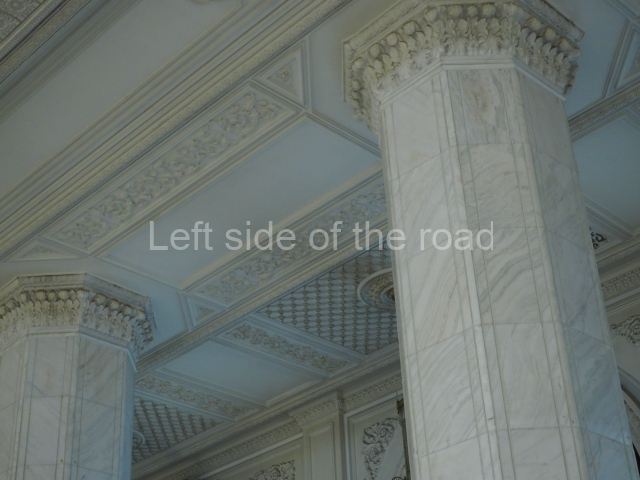

The building was erected with construction materials produced in Romania, amongst which: 1,000,000 cubic meters of marble, 550,000 tons of cement, 700,000 tons of steel, 2,000,000 tons of sand, 1,000 tons of basalt, 900,000 cubic meters of rich wood, 3,500 tons of crystal, 200,000 cubic meters of glass, 2,800 chandeliers, 220,000 sqm carpets, 3,500 sqm leather.

Interesting is the fact that, for the construction of the Palace of Parliament, all the foam models were made on a scale of 1/1000 presenting the entire Bucharest city, including the streets, plazas, buildings, houses and monuments, also with certain details.

In 1989, when the Revolution started, only 60% of the building was finalized. At that moment, giving the resentfulness of the population against the symbols of the past era, the demolition of the building was taking into account. Yet, following the economic considerations, it was decided to complete the construction as it was cheaper than demolishing it. Thus, between the years 1992 and 1996, the construction started again.

Now, when you are looking at this massive construction, you can see:

- the largest administrative building (for civil use), as confirmed by the Guinness World Records Book

- the 3rd place worldwide by its volume

- the heaviest and the most expensive building in the world

With approximately 1000 rooms of which 440 are offices, more than 30 ballrooms, 4 restaurants, 3 libraries, 2 underground parking lots, 1 big concert room, 1 unfinished pool, and thousands of square meters in which no one knows what is happening, the Palace of Parliament offers you contradictory feelings every time you step on its doorstep.

Text above from Visit Bucharest.

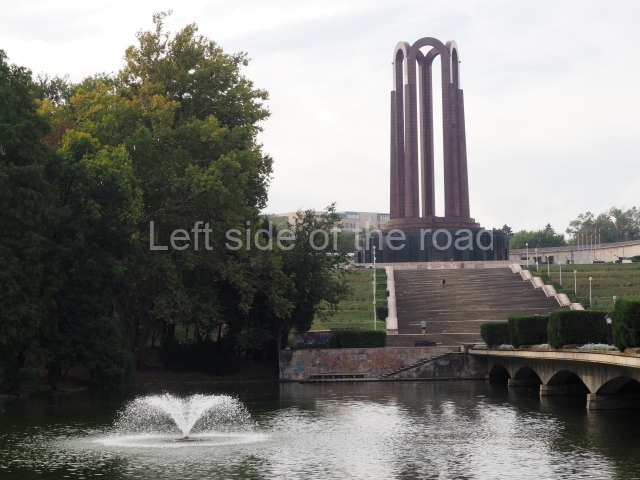

People’s Palace from Izvor Park

It’s difficult to make an analysis of the People’s Palace building in Bucharest because today, so many years after it was first planned, so many years after the society (which was nominally Socialist) collapsed it’s difficult to put the building in its proper context.

It was constructed as part of the plan to rebuild the centre of Bucharest after much of it was destroyed in the 1977 earthquake. A general, overall reconstruction of the city centre necessarily meant there would have to be further ‘destruction’. Those buildings, many thousands of them, which were not destroyed in the earthquake were later demolished as part of the new plan.

Whatever a Socialist country would have done in such circumstance would have invited criticism from the West so Romania was in a lose, lose trajectory from the very beginning. Critics would have wanted to retain more of the Old Town – with the result that there would be even more decaying buildings in the centre of Bucharest than there are now.

The problem with the People’s Palace and looking at it in the context of the plan for Bucharest centre, is that only a part, possibly less than half, of the project was ever fulfilled. It would have been a decades long project but Socialist Romania only had a little over ten years left to complete the plan.

The People’s Palace sits on a hill, looking down towards what is now called the Civic Centre. The plan for the reconstruction of the city, or more accurately to say not just the reconstruction but a complete rethinking of the city centre, involved the construction of thousands of apartments and other, major public buildings.

Being located on a high point, the highest point for a long way around, the People’s Palace is a focal point but was still part of the general reconstruction plan. The building itself was still far from completion when Romanian society changed/collapsed/transformed in the 1990s. There was even a suggestion of knocking the building down rather than completing it but it was decided that demolition would be as expensive as completion so construction moved on, although slowly.

The building itself is, in some sense, slightly schizophrenic. The interior uses some of the finest materials and even though the plan by Ceaușescu and his government was to use only indigenous materials on the interior decoration this was mocked by critics of the regime. However, when restored capitalism decided to continue with the construction of the building it followed the same policy – and now claims credit for such an approach in the commentary of its official tours.

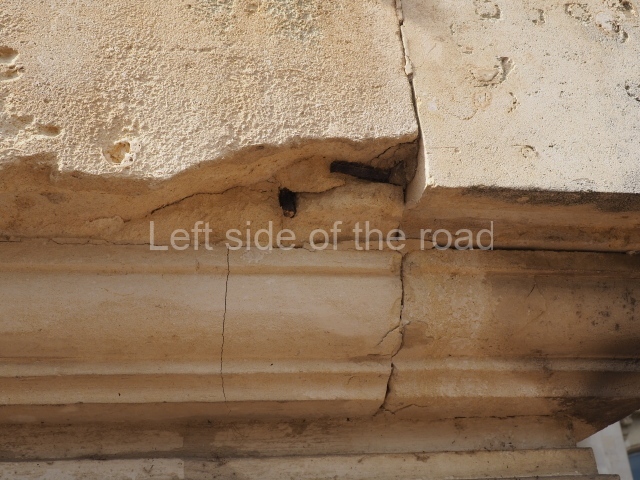

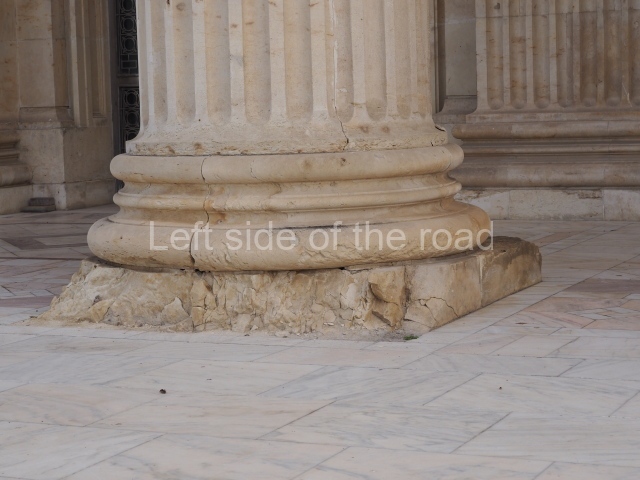

So, we have the finest (and probably more expensive) indigenous materials used on the interior but corners were definitely cut on the outside of the building. Looking at it from a distance you get the impression the building is made of stone, however that’s not the case. It’s a concrete structure, sometimes faced with bricks and then stucco placed on top to give the impression of cut and worked stone.

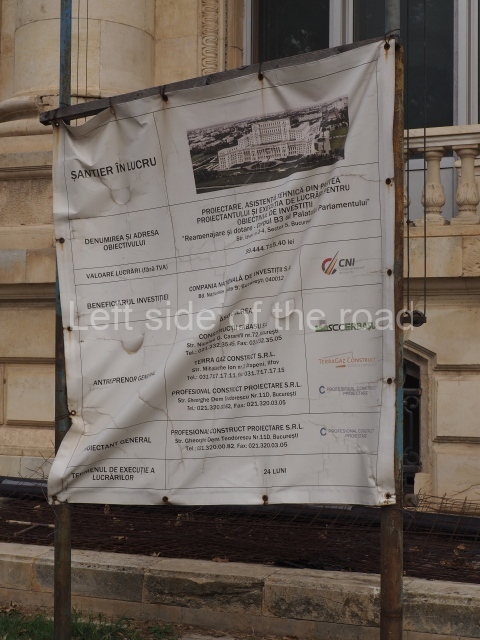

At the moment, in 1924, the exterior of the building is undergoing a major and very expensive repair and renovation. (A sign outside the building indicated that a sum equivalent to about £10 million – surprisingly not from the EU – is estimated for this restoration. That is, before it goes way over budget.) From my observations one of the reasons for this is that the stucco attached to the framework of the building is starting to decay. And the cause of that decay is the rusting of the iron rods and webbing that was used to give strength and structure to the stucco. The chemical reaction caused by the rusting has broken down the stucco and there are many places where this is obvious, especially at the ground level.

Decaying façade

When it comes to the interior it’s difficult to know exactly what the original plan was. There’s nothing in the internal decoration that’s really distinctive to Romania and especially no reference to any form of Socialism – which you would see in many buildings constructed in the Soviet Union during its Socialist (and even its Revisionist) period, in the so-called ‘Seven Sisters’, for example.

It seems more of a mish mash of influences from other countries and other periods – but all produced using Romanian materials. I’m assuming the vast majority of the interior was completed post-1990 so that’s not really a surprise. If it would have been different if the counter-revolution of the 1990s had not taken place is a question I’m unable to answer.

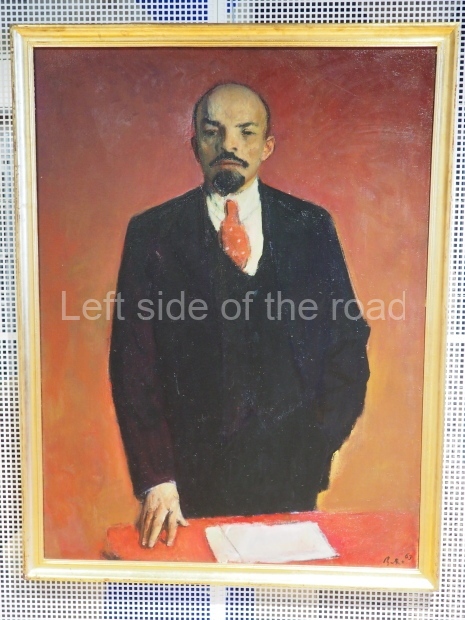

There are ‘empty’ spaces where it’s possible the original plan was to include examples of Romanian Socialist Realist art, representations of workers’ struggles and achievements, but following the re-establishment of open capitalism there would never be agreement on what should fill those spaces. A similar ‘dilemma’ can be witnessed in the Moscow Metro where images of JV Stalin were removed but nothing, often, replacing them.

One of the areas readily providing public access to the building is National Contemporary Art Museum. This is at the back of the building and access has been changed due to the renovation work. In the autumn of 2024 most of the galleries were closed ‘for renovation’ and if there was an opportunity to view Romanian art from the period between 1945 and 1990 before those closures it’s unlikely to be possible when the galleries reopen at some time in the future. If that art was on show it might have provided a clue to what would have appeared in the many halls and corridors of the building – when its name was the People’s Palace and not its name now which is Palace of the Parliament. (It’s difficult to appreciate Romanian Socialist Realist art as there are few examples on display. This is limited, more or less, to the mosaic in the entrance hall of the Military Museum and another mosaic at the back of what is now the Peasant Museum but was originally the Museum of the Romanian Communist Party.) On my visit in 2024 there were a few locations where some temporary (religious) images had been placed in some of the vacant lots – whether that is a sign for the future only time will tell.

Returning to the plan for the overall transformation of the centre of Bucharest an idea can be gained by those buildings that were constructed (or sometimes only begun), mainly for government, military or educational purposes. A number of those can be seen from the top of the People’s Palace (a good place to go is the café of the Contemporary Art Museum). These include the Romanian Academy to the south; the (now Marriott) hotel and the Ministry of Defence to the west, and the University buildings (some not completed) to the north-west.

What you also find, and which I find quite interesting when discussing significant Socialist related locations in all the post-Socialist societies, is the construction of principally religious buildings close to, if not on, those sites. When this was carried out after the European invasion of the Americas, principally in South America, the Catholic Church called this practice ‘the extirpation of idolatry’. In the context of Peru, for example, that meant the physical destruction of the religious sites of the indigenous people or the construction of Christian churches on top of Incan temples. (This was just a continuation of what the early Christian church did to Roman buildings.)

‘Extirpation of Idolatry’

Examples of this in other post-Socialist countries would be the building of an Orthodox Church just below the magnificent monument to the heroism of the people of Stalingrad (The Motherland Call!) on Mamayev Kurgan; the construction of Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Cathedrals and, now, the largest mosque in the Balkans, in Tirana, Albania; and in Bucharest the present building of the ‘People’s’ Redemption Cathedral right next to the People’s Palace – and I don’t believe its location is accidental.

What I find interesting about the construction of this cathedral is that it, too, is not what it seems. This is yet another concrete structure with a stuck on, cheap façade. With an astounding budget of €250 million I think the Romanians are being robbed. The mosque in Tirana cost a mere €30 million.

So, now post-Socialist countries are not constructing buildings for the people but shrines to fear, superstition and ignorance.

Interior

Architect;

Anca Petrescu (principal), plus many others

Specifications;

Number of rooms;

1,100

Height;

84 m (276 ft)

Size;

240 m (790 ft) long, 270 m (890 ft) wide

Number of floors;

12

Floor area;

365,000 m2 (3,930,000 sq ft)

Location;

Strada Izvor 2-4

GPS;

44°25′39″ N

26°5′15″ E

Completed;

1997

Visiting;

Opening hours;

- March – October, daily 09:00 am – 5:00 pm (last round at 4:30 pm)

- November – February, daily 10:00 am – 4:00 pm (last round at 3:30 pm)

For reservation;

It’s not possible to book a tour online (unless you want to pay the premium to a tour company).

- Bookings for 1 to 9 people can be made only by phone, 24 hours prior to the visit, between 09:00 – 16:00, at the following telephone numbers: + 40 733 558 102 or +40 733 558 103. The easiest way to do this is to ask the staff at your accommodation to make the call. Payment is made at the time of the visit.

The tour takes about an hour. You need to have your passport, the original as a copy is not acceptable, as it will be scanned as they do at airports.

Ticket prices:

Standard Tour

- Adults: 60 lei / person

- Students: 20 lei/person (19 – 26 years old, with student card approved)

- Children: 10 lei / person (7-18 years)