Syri i Kalter, the Blue Eye

Syri I Kaltër, the Blue Eye is one of the natural attractions in the Saranda area in southern Albania, especially if you are not interested in the beach or are looking for a change. A visit here can also be put together with a day trip to Gjirokastra from Saranda.

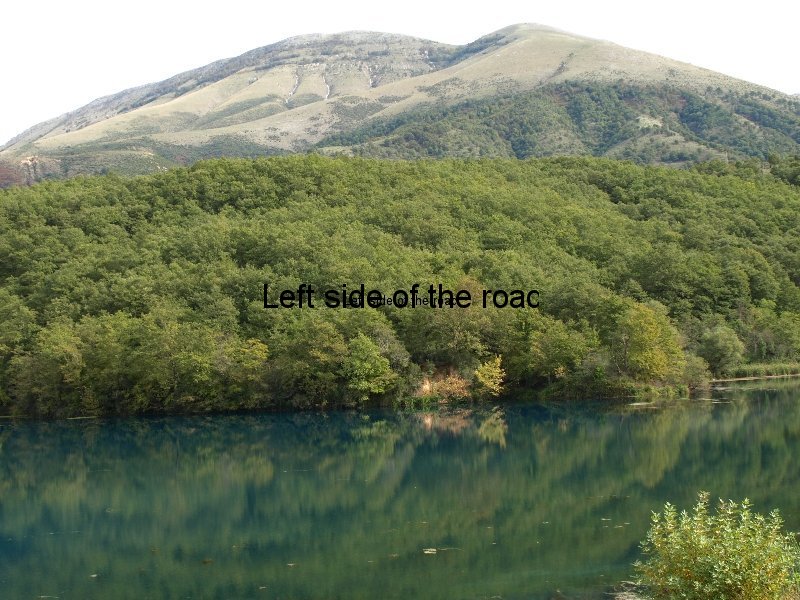

If you look at the pictures and read some of the descriptions the Blue Eye seems to be quite impressive indeed. It’s one of the sources of the river which supplies the water to operate the two hydroelectric plants at Bistricë, in the direction of Saranda (one of these had a visit from Sali Berisha, the Albanian Prime Minister, at the beginning of November 2012 to open a new electricity generating project).

But the problem is that, as it’s a karst spring that has worked its way through the limestone over millions of years. The water will be that which has worked its way into Mount Mali Gjerë and then found its escape route. Perhaps the spectacle is more impressive just after a wet winter where the force of water may be greater. Visiting in the autumn the force was not as great as would give rise to the naming of the spring in the first place.

According to the information board the force of the water was 8.8 cubic metres a second in 1980, but continually fluctuates. If there has been a series of dry years I assume the force reduces and it would take a series of wet years to really understand why it received its name.

As it is you are aware that the water is coming up with some force, but that force has not been strong enough to prevent the growth of underwater vegetation which means that the circular shape of the hole is somewhat disguised.

But it’s a pleasant few hours out in the countryside, especially if weather is good, and you never know when these natural phenomenon decide to put on their best show. After all, it took a minor earthquake to wake up Geysir in Iceland.

Practical Information:

Transport:

Any bus or furgon that travels the route from Saranda to Gjirokastra passes by the side road going to the Blue Eye. From Saranda it takes around 40 minutes and costs between 100 and 200 leke (I was charged the two extremes on a return trip – don’t know if ‘tourist prices’ are starting to become more common now). The bus will normally drop you off at the side road from where you have to walk. There are more buses in the morning, existing in the afternoon but with reduced frequency.

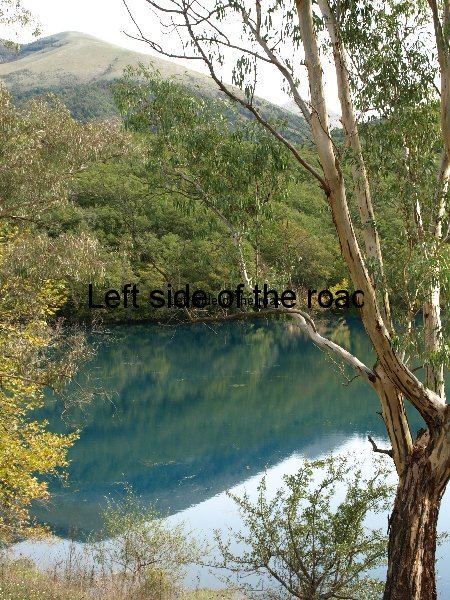

Taking the side road, that leaves northwards off the main road, you walk for about 5 minutes to reach a dam and a control point. There’s a sign which indicates that entrance is 50 leke for visitors arriving on foot but I wasn’t asked for anything. Continue along the dam, with the lake on your right and then just follow this road as it climbs slightly around the edge of the lake. After about 20 minutes you’ll hear the sound of running water and a few minutes later arrive at the end of the road, with the bars/restaurants. Cross the narrow foot bridge, take the path to the left which arrives at the Blue Eye in about 50m. There’s a viewing platform where you get the opportunity to look down into the ‘Eye’ and an information board giving you an idea of what is happening under your feet.

Accommodation

There are a couple of bar/restaurants in the vicinity of the Blue Eye, although only one of them is open all year round – and even that offers a limited service outside the weekend. However the Syri i Kaltër Komplexs Turistik, which is at the fall end of the valley, away from the entrance road, does offer some very basic, but consequently very cheap, accommodation. They have 5 cabins which will each sleep four (one double bed and two singles) and cost €20 per night.

They smelt musty when I was there but that was at the end of the season and it was starting to get a bit damp. In the height of the summer they get booked up some time in advance but outside of that short couple of months chances are that they would be available. There’s no website but they can be contacted by phone on +355 69 24 38 201.

There is a large restaurant connected to the complex but this will not be guaranteed operating in the off-season. It’s location would be perfect on a hot summer’s day as the veranda is built so that it extends over another stream that has come down from the hills above.

If you like isolation and going to sleep to the sound of running water this might be a place to stop if you’re travelling in a group. Bring your own food just in case but if you don’t there are a couple of bar/restaurants just up from the side road that takes you to site, in the direction of Gjirokastra, by the petrol station. A speciality here is the fresh water fish.