Elektrozavodskaya station

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Elektrozavodskaya – Line 3

Work on the Moscow metro’s third stage was delayed – but not stopped – by the war. Elektrozavodskaya station, named after a nearby light bulb factory, was opened in 1944.

Elektrozavodskaya – 12 – light bulb factory

Elektrozavodskaya (Электрозаводская) is a Moscow Metro station on the Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line. It is one of the most spectacular and better-known stations of the system. Built as part of the third stage of the Moscow Metro and opened on 15 May 1944 during World War II, the station is one of the iconic symbols of the system, famous for its architectural decoration which is work of architects Vladimir Shchuko (who died whilst working on the station’s project in 1939) and Vladimir Gelfreich, along with participation of his student Igor Rozhin.

Elektrozavodskaya – 03 – Hammer and sickle

The station serves the Basmanny district and is located on the Bolshaya Semyonovskaya Street, next to the Yauza River. The railway station Elektrazavodskaya of the Kazan direction is also located nearby. In May 2007, the station was closed for a year during which the escalators were completely replaced, along with the floor panels. Most of the details and finishes including Motovilov’s bas-reliefs were refurbished. The station was reopened on 28 November 2008.

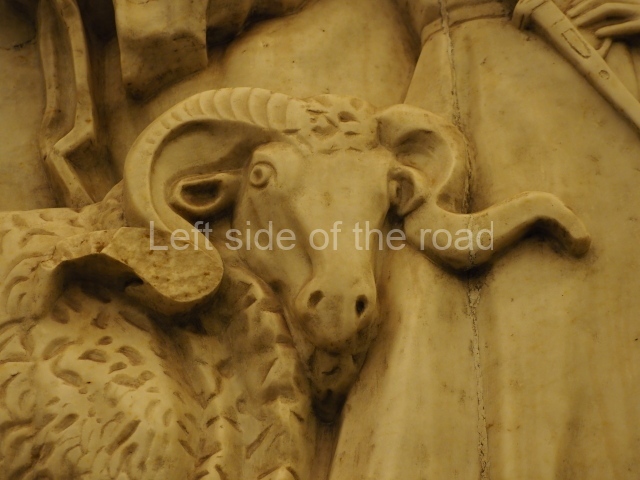

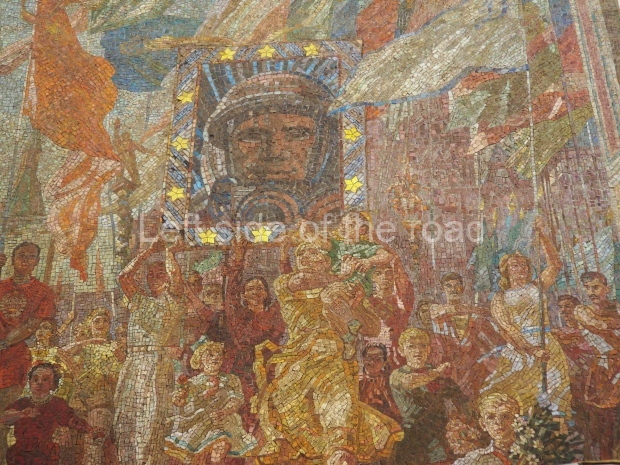

Elektrozavodskaya – 16 – wheat harvesting

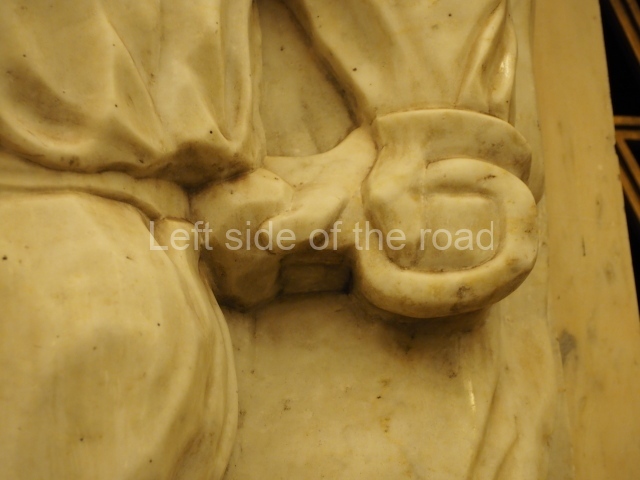

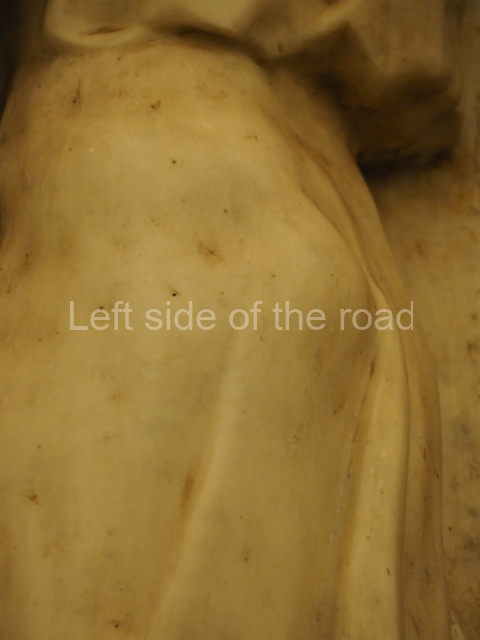

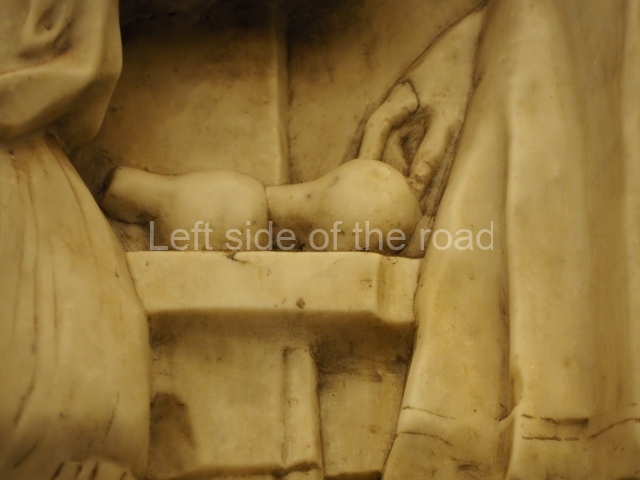

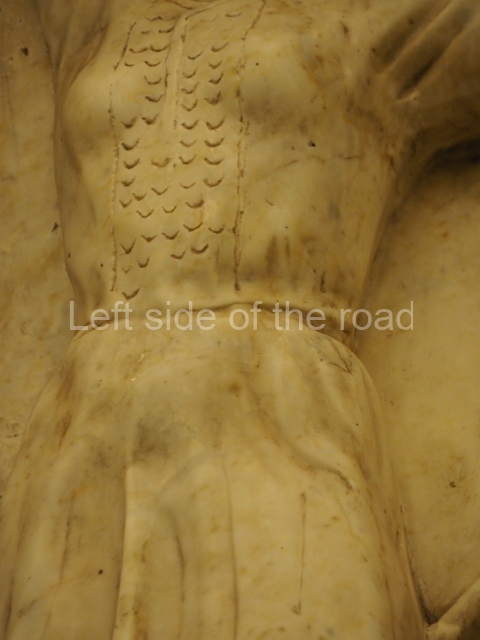

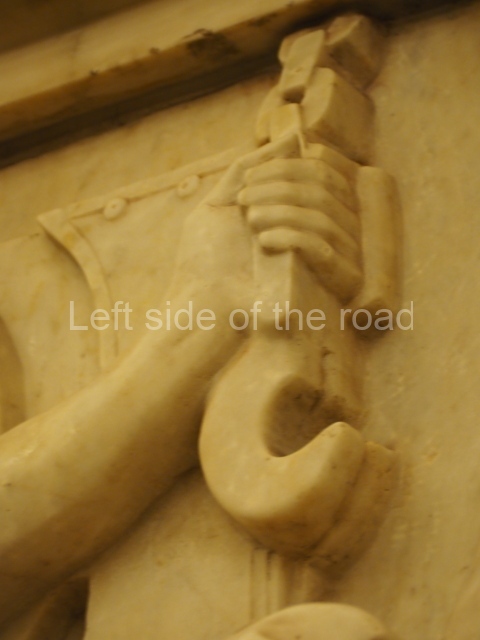

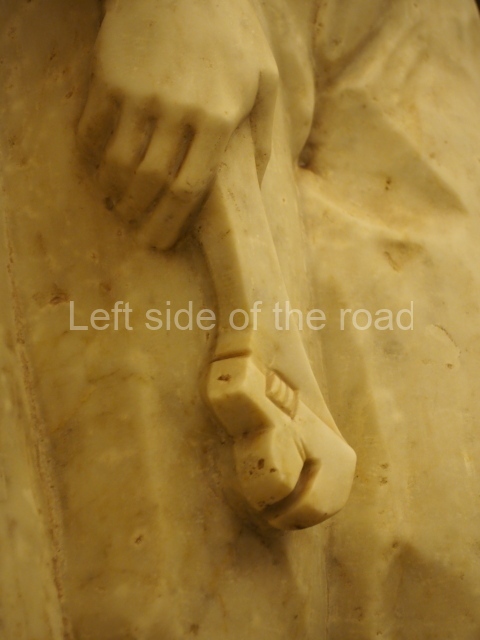

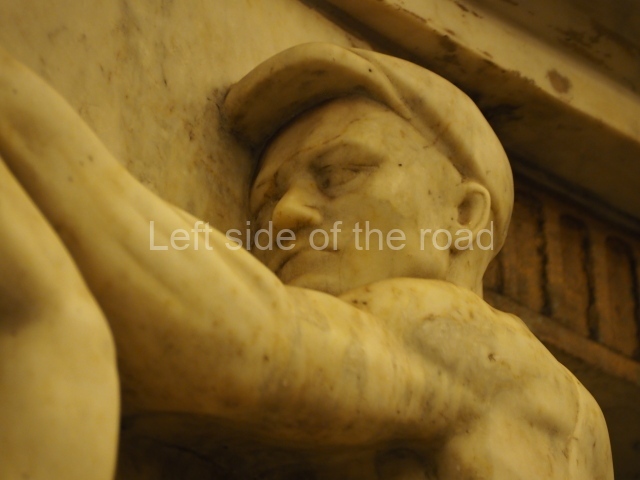

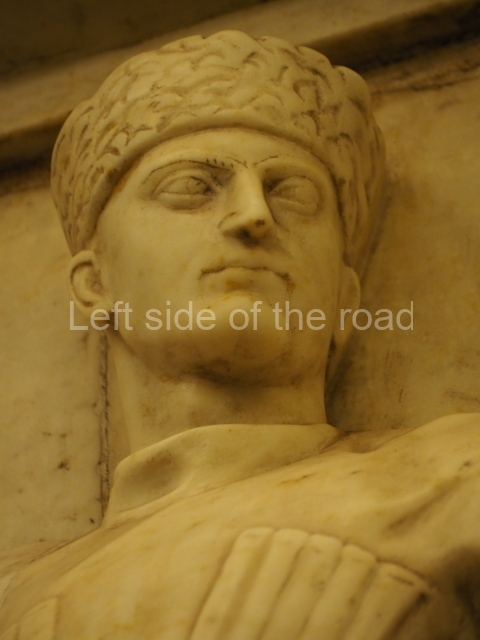

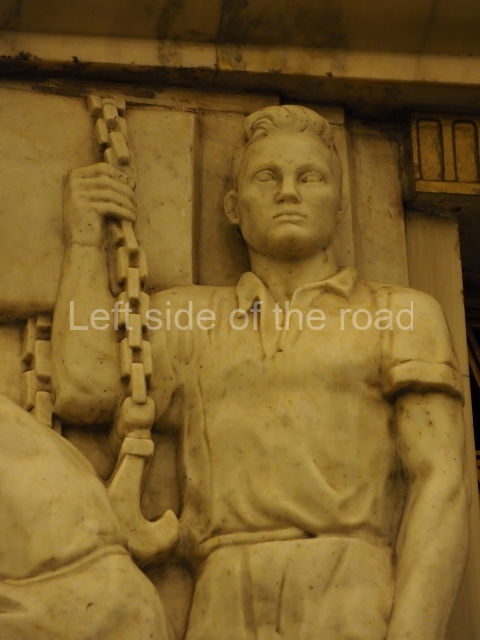

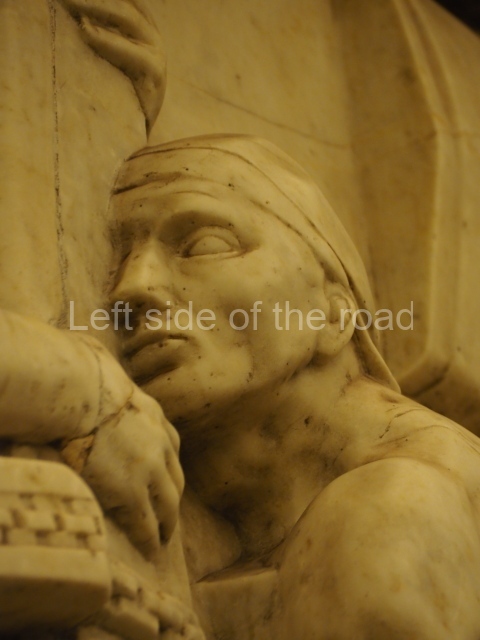

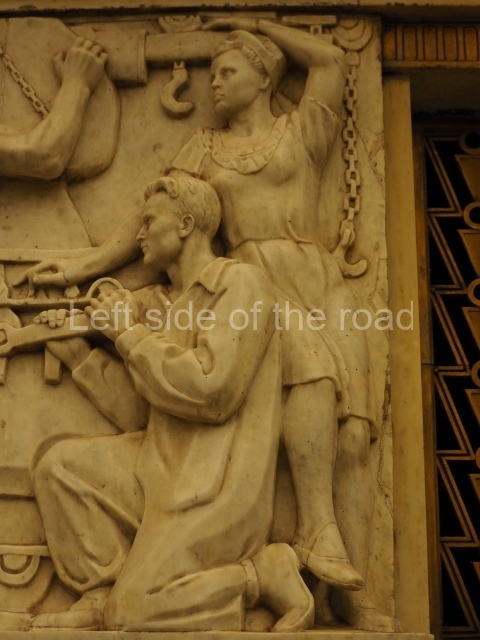

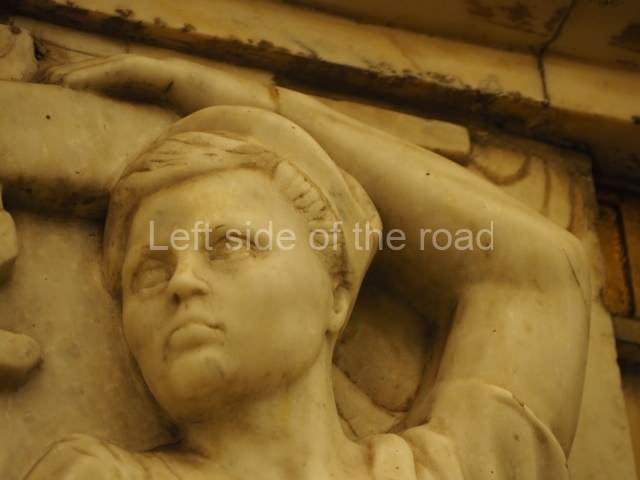

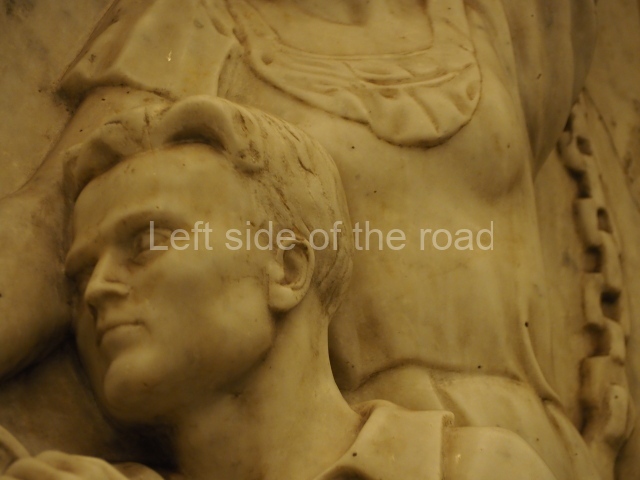

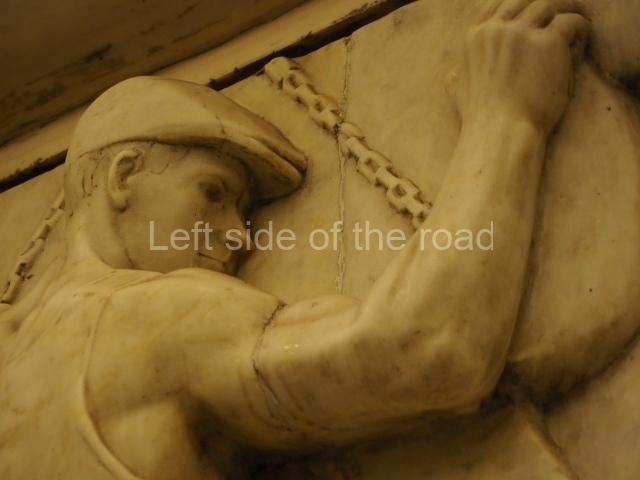

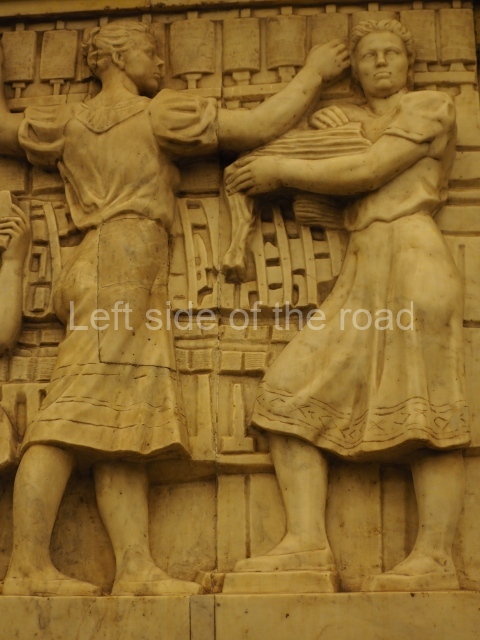

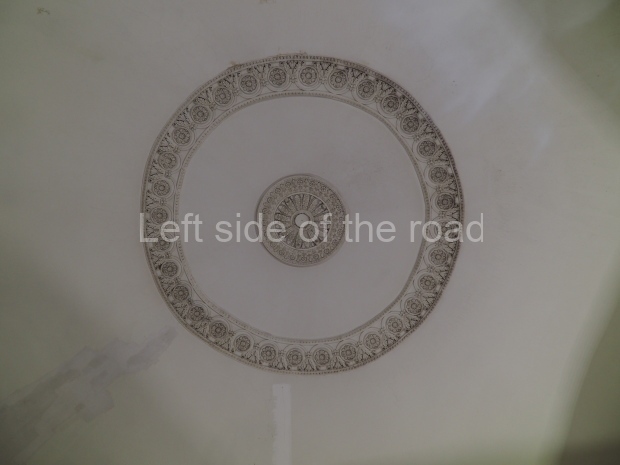

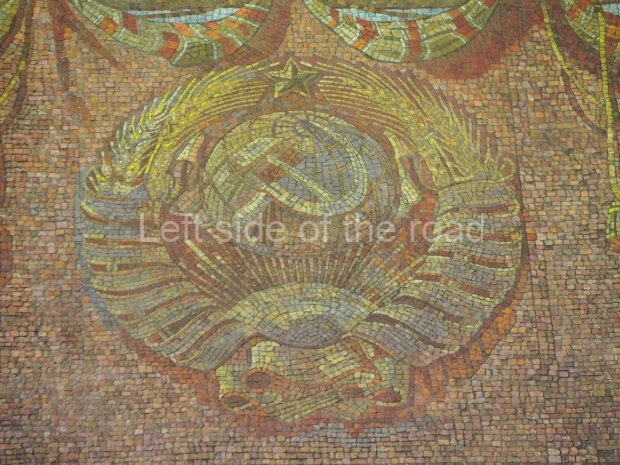

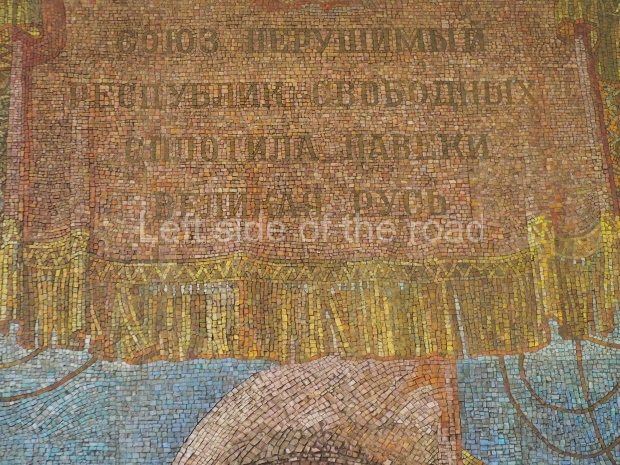

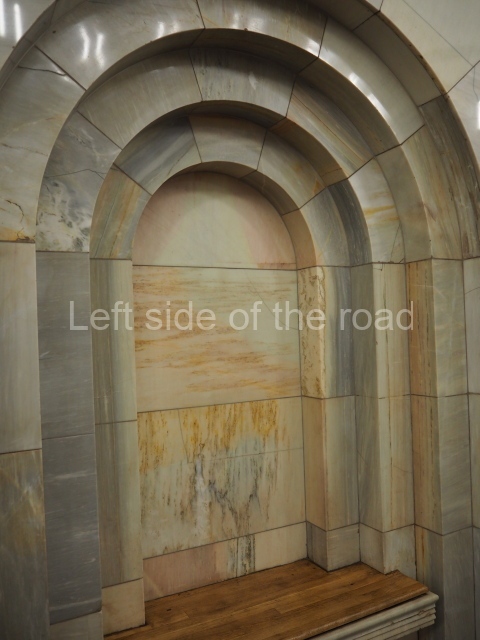

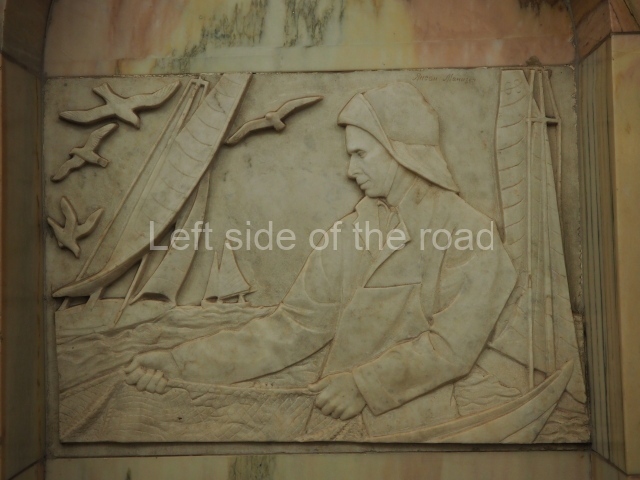

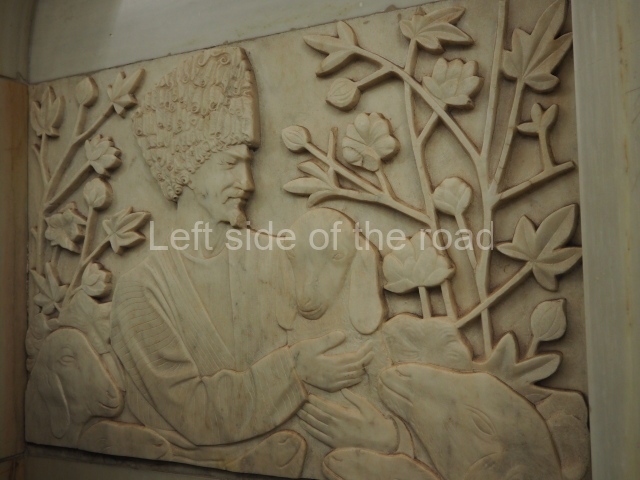

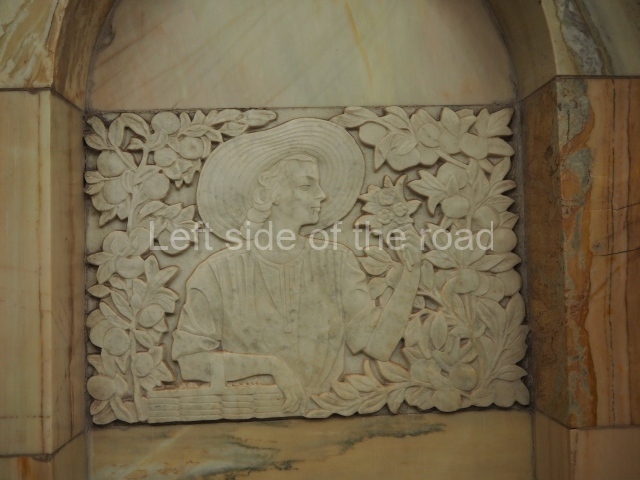

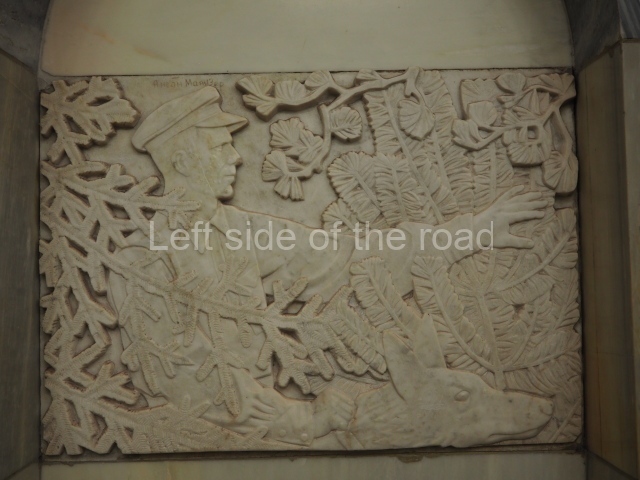

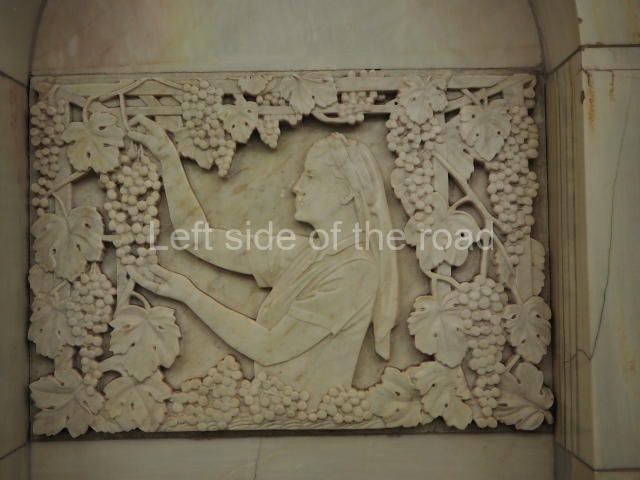

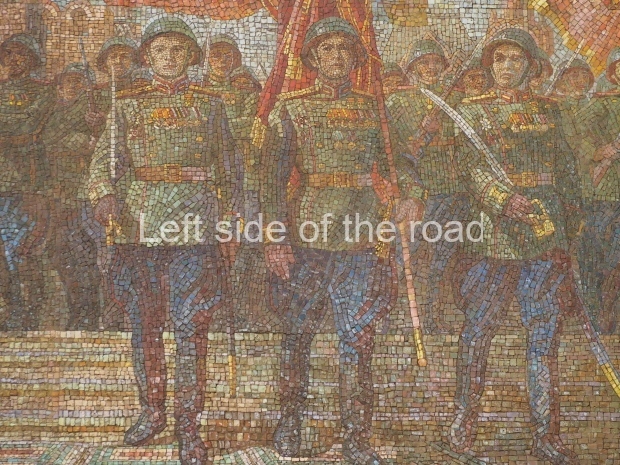

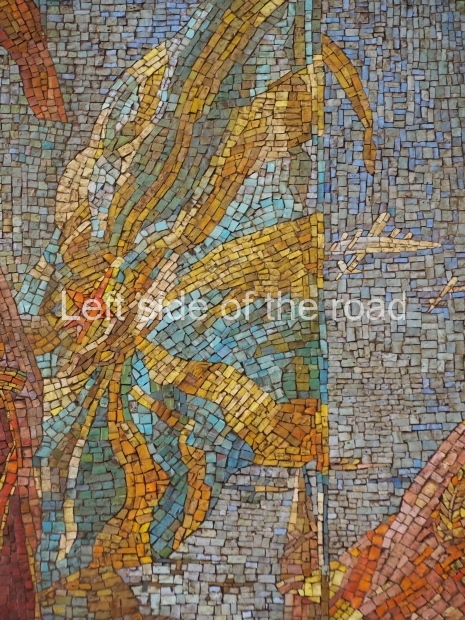

Named after the electric light bulb factory nearby, the preliminary layout included Schuko’s idea of making the ceiling covered with six rows of circular incandescent inset lamps (of which there were 318 in total). However the outbreak of World War II halted all works until 1943 when construction resumed. Gelfreich and Rozhin finished the design by adding an additional theme to the station of the struggle of the home front during the war, which is highlighted by the 12 marble bas-reliefs on the pylons done by Georgiy Motovilov. The rest of the station’s interior features most of the 1930s plans including powder-ballada marble on the rectangular pylons (the outside faces have sconces and decorative gilded grilles depicting the hammer and sickle), red salietti marble on the station walls, a dark olive duvalu marble on the socle and a chessboard layout on the main platform floor of granite and labradorite.

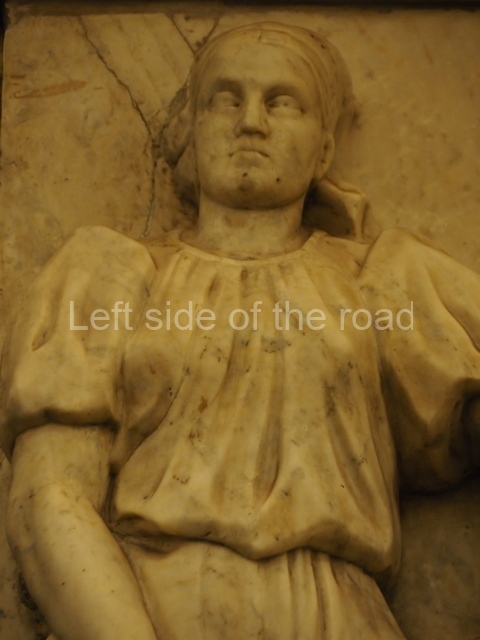

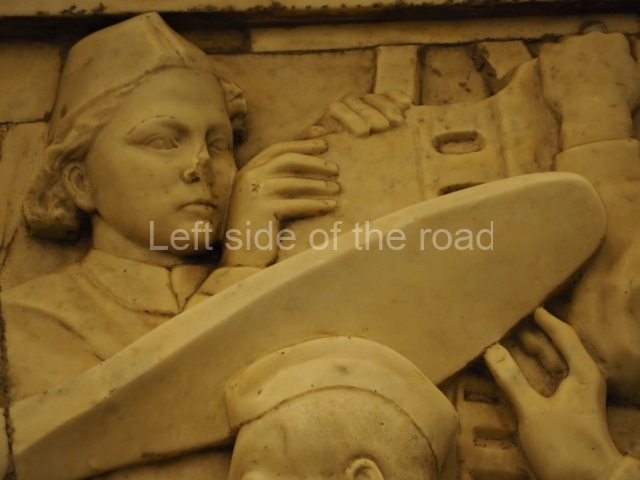

Elektrozavodskaya – 21 – aircraft woman

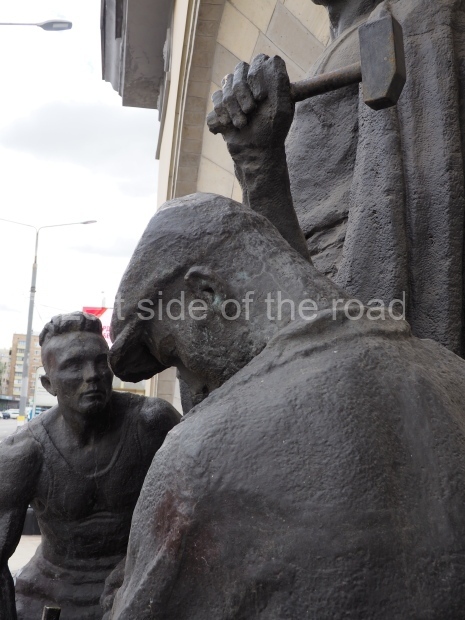

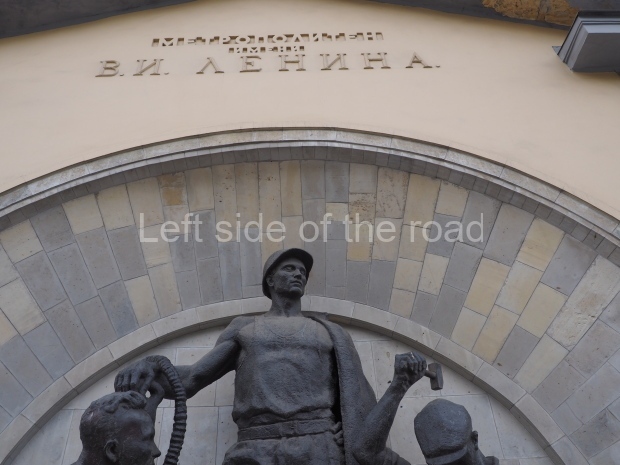

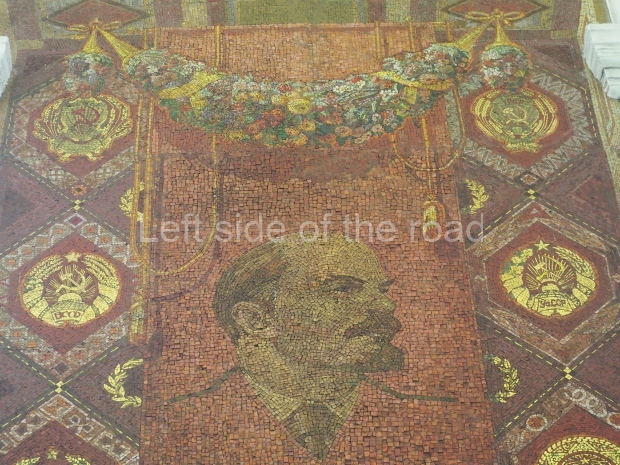

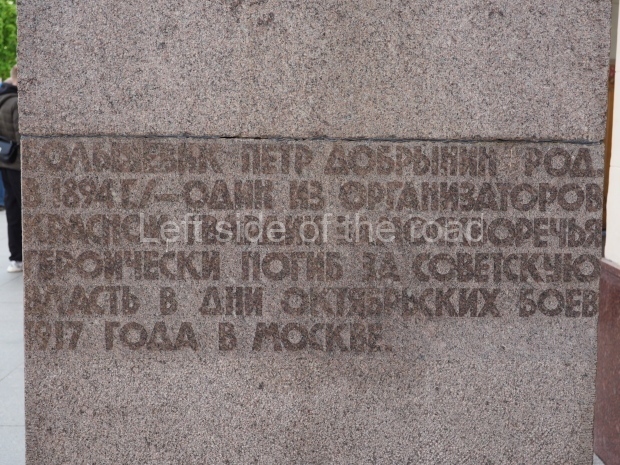

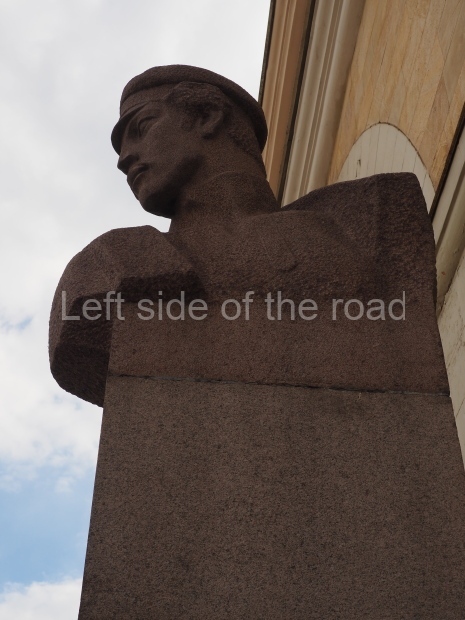

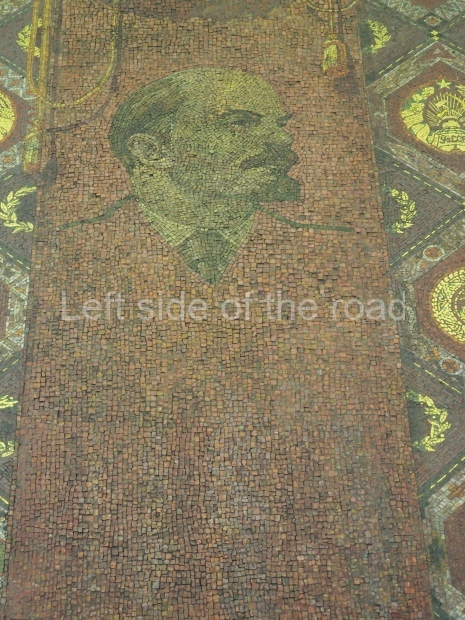

The station’s hexagonal shaped vestibule, features a domed structure on a low drum, on the corner niches of which are six medallions with bas-reliefs of main pioneers in electricity and electrical engineering: William Gilbert, Benjamin Franklin, Mikhail Lomonosov, Michael Faraday, Pavel Yablochkov, and Alexander Popov along with their pioneering apparatus. The interior of the vestibule is further punctuated by the same bright red salietti marble. Outside the vestibule in the archway there is a sculpture to the metro-builders by Matvey Manizer.

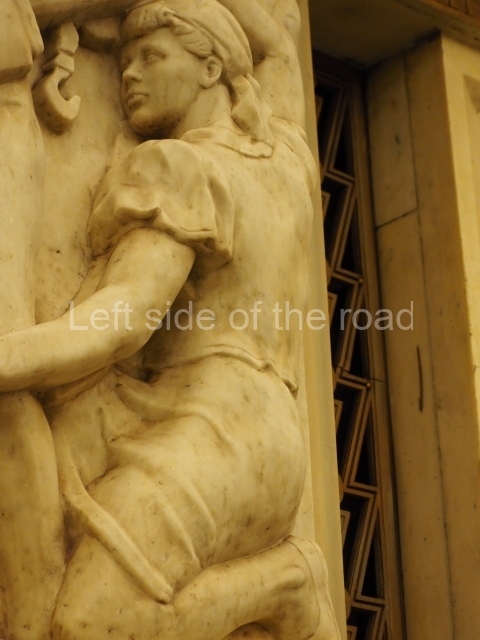

Elektrozavodskaya – 19 – road building

The station’s legacy was that it serves as a bridge between the pre-war Art Deco-influenced Stalinist architecture as seen on the second stage stations and their post-war counterparts on the Koltsevaya Line. Both Genrikh and Rozhin were awarded the Stalin Prize in 1946 for their work.

Elektrozavodskaya – 103 – view towards escalators

Text above from Wikipedia.

Elektrozavodskaya

Date of opening;

15th May 1944

Construction of the station;

deep, pier, three-span

Architects of the underground part;

V. Gelfreih, I. Rozhin in collaboration with P. Koplansky and L. Shagurina

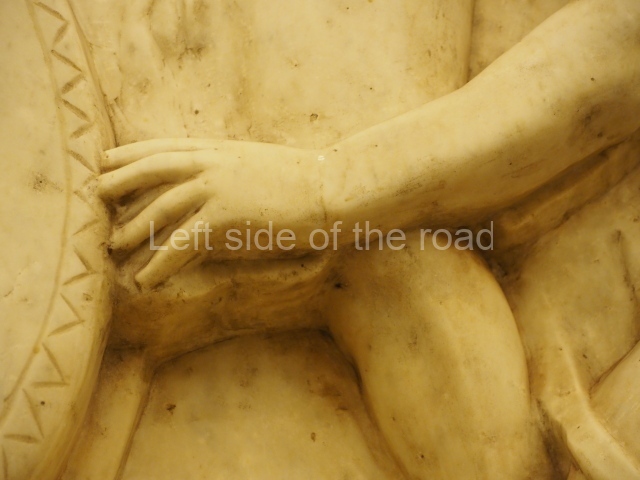

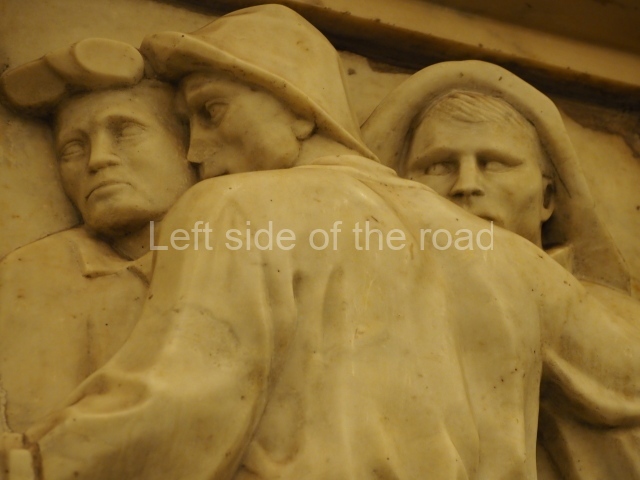

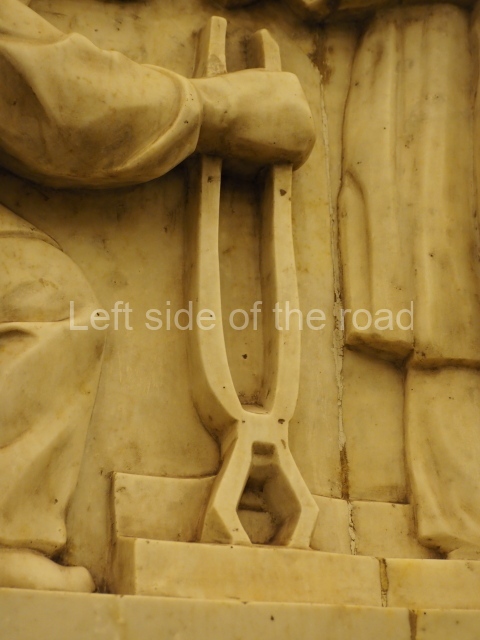

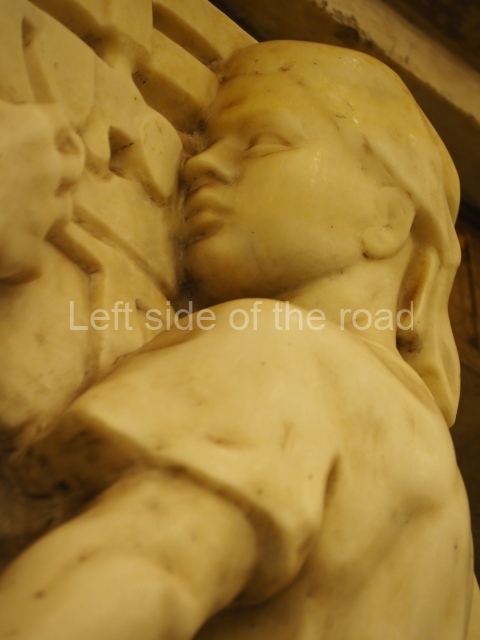

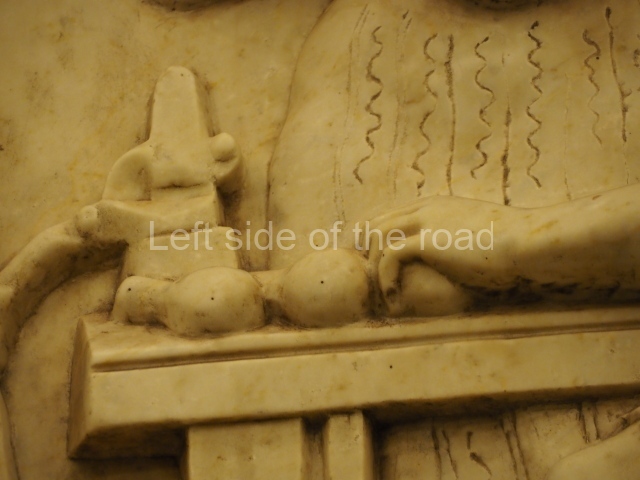

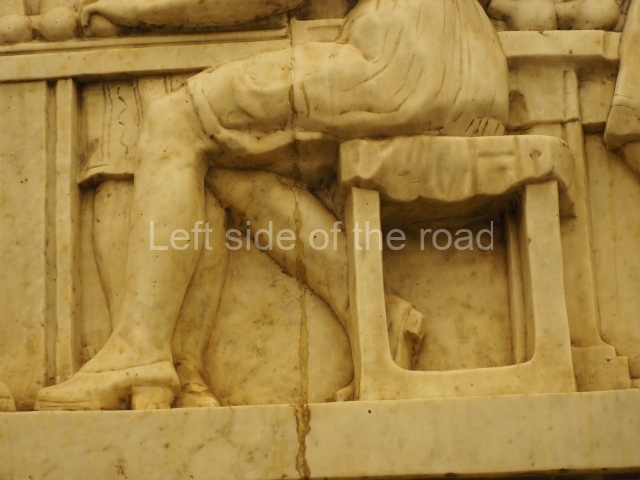

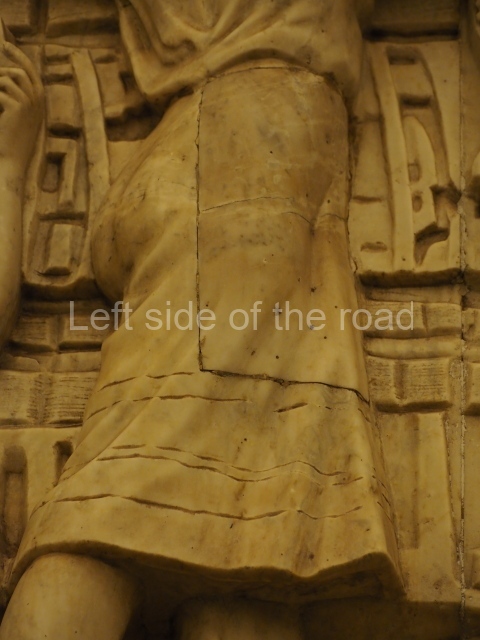

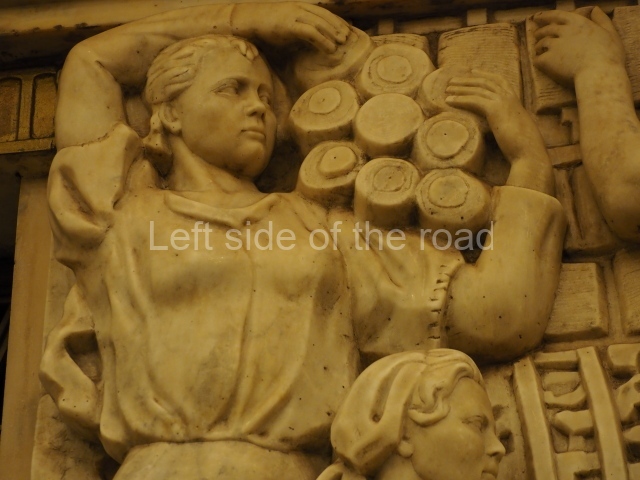

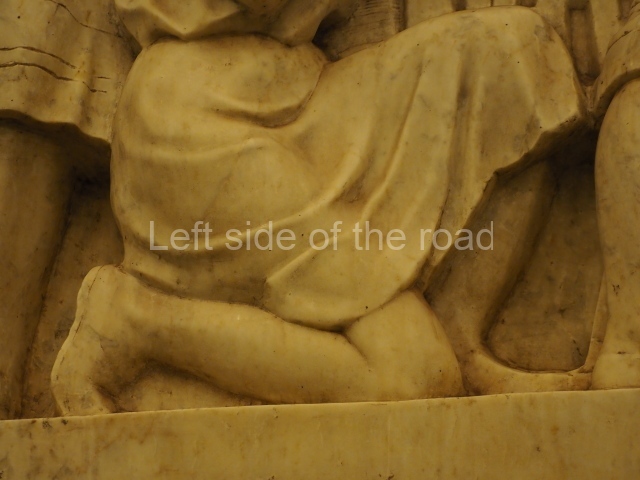

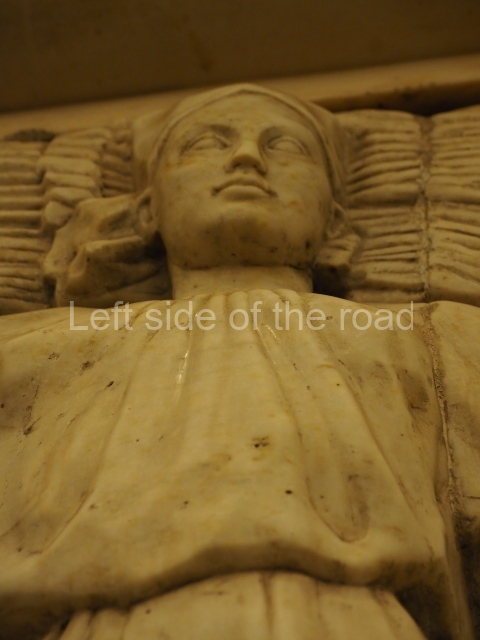

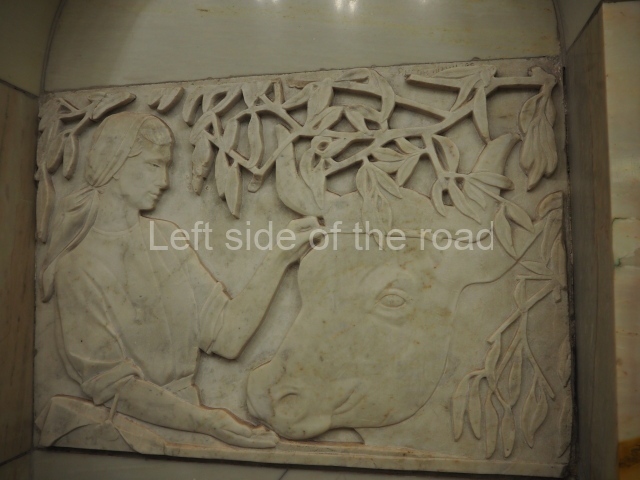

The whole vault of the central hall is covered with 300 round coffers. An ordinary incandescent lamp is in each coffer – Moscow Electric-bulb Plant is located nearby. The pylons are decorated with white and greyish-yellowish marble of the Prokhoro-Balandinskoye Deposit. There are marble high relieves on the pylons just below the base of the vault on the side of the central hall. The topics of the relieves are traditional of the Moscow Metro, such as ‘Foundry’, ‘Forge shop’, ‘Harvesting’, ‘Vehicle assembling’, ‘Tank assembling’, ‘Gun manufacturing’. However some sketches are rare or even unique. The left high relief of the first pylon pair (starting from the western wall) presents girls manufacturing lamps. Workers manufacturing insulators for transmission lines are on the opposite pylon. The right high relief of the first pylon (starting from the exit) presents girls and a pilot installing a propeller to an airplane. Opposite is a female brigade headed by a foreman, building road and laying asphalt. So the authors wanted to immortalize the labour feat of female workers on the home front.

The chessboard of the floor is made of grey marble and black gabbro banded with pink-yellow marble from the Crimean Biyuk-Yankoy Deposit. The edging contains a meander made of black gabbro.

The walls are decorated with bright red marble with numerous intricate white inclusions from the Georgian Salieti Deposit.

Text from Moscow Metro 1935-2005, p89

Elektrozavodskaya, Moscow, 1961

Location:

GPS:

55.7817°N

37.7037°E

Opened:

15 May 1944

Depth:

31.5 metres (103 ft)

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

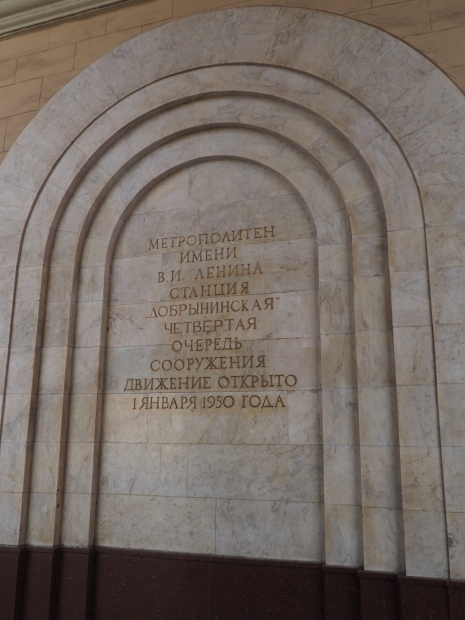

A second picture gallery contains images from ther vestibule area and also of a large sculpture that located outside the entrance building.