Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Pushkinskaya – Line 7

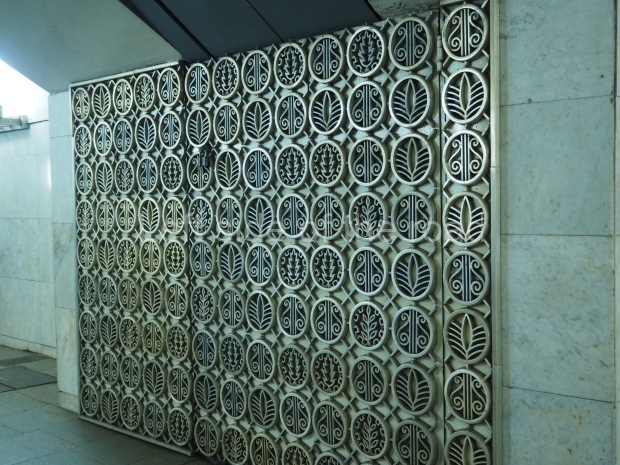

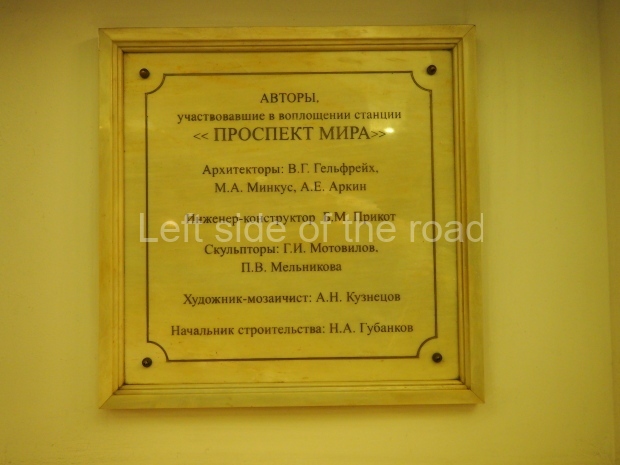

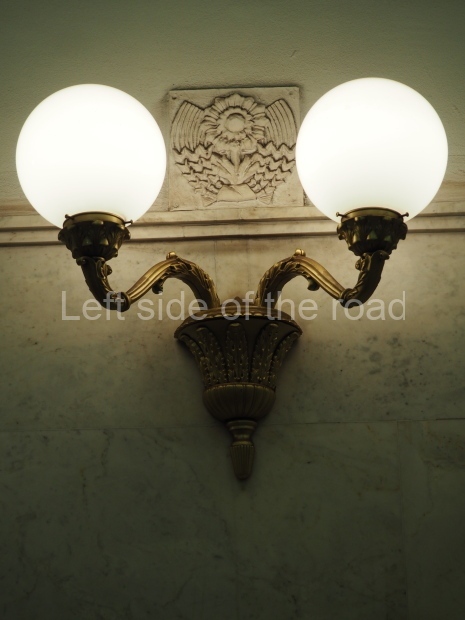

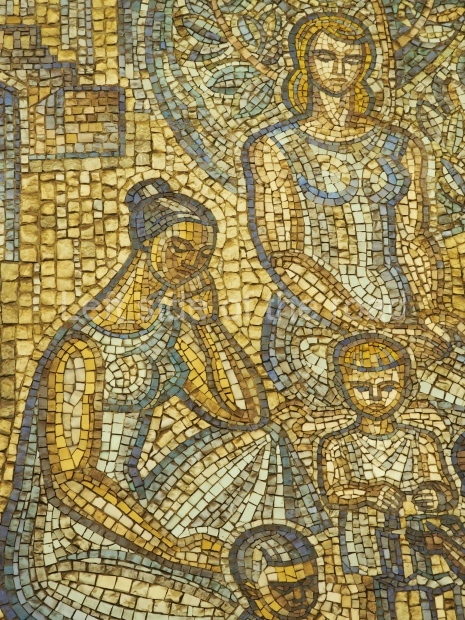

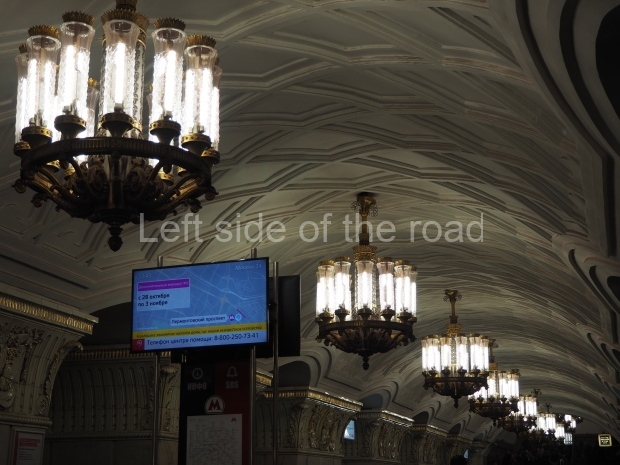

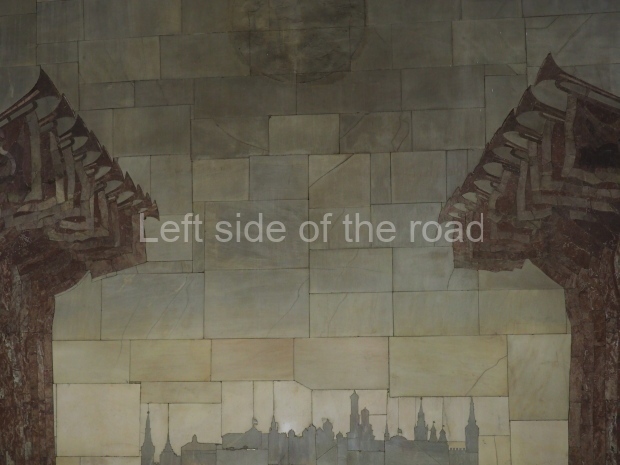

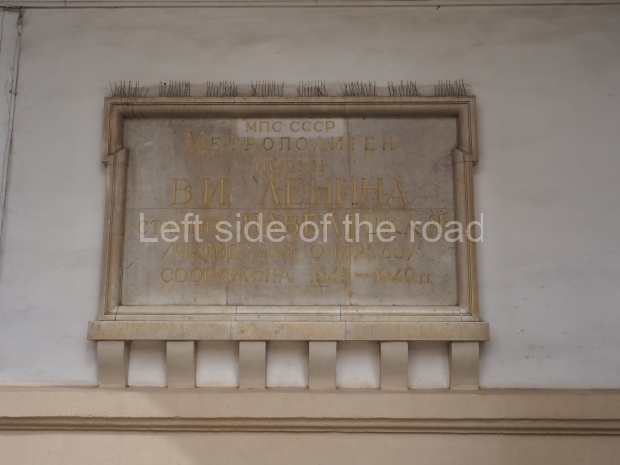

Pushkinskaya (Russian: Пушкинская) is a station on Moscow Metro’s Tagansko-Krasnopresnenskaya Line. Opened on 17 December 1975, along with Kuznetsky Most as the segment which linked the Zhdanovskaya and Krasnopresnenskaya Lines into one. Like its neighbour, the station was a column tri-vault type, which had not been seen in Moscow since the 1950s. Arguably the most beautiful station on the Line, the architects Vdovin and Bazhenov took every effort to make it appear to have a ‘classical’ 19th century setting. The central hall lighting is created with stylised 19th century chandeliers with two rows of plafonds appearing like candles, while the side platforms have candlesticks with similar plafonds. The columns, covered with ‘Koelga’ white marble are decorated with palm leaf reliefs and the grey marble walls are decorated with brass measured insertions based on the works of the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. The grey granite floor completes the appearance of the masterpiece. Architecturally the station put the final stop to the functionality economy design of the 1960s and went against Nikita Khrushchev’s policy of struggle to avoid decorative ‘extras’, which left the stations of 1958–59 greatly altered in their design.

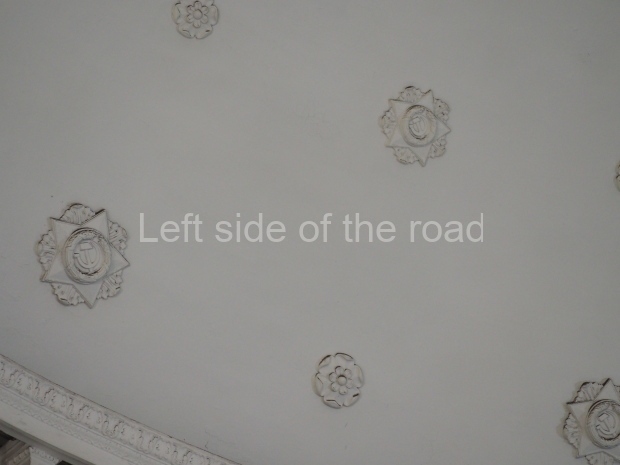

The station’s original vestibule, with its magnificent cessoned ceiling from anodized aluminium (architects Demchinskiy and Kollesnikov) is situated under Pushkinskaya Square of the Boulevard ring, the centre of Moscow’s nightlife, and is linked with subways to the square and to Tverskaya Street. In 1979 it was combined with the Gorkovskaya (now Tverskaya) station of the Zamoskvoretskaya Line. The opposite end was decorated with a bust of the great poet himself (architect — Shumakov), however in 1987 a pathway was opened to the underground vestibule of the two escalator cascades of the Chekhovskaya station of the Serpukhovsko-Timiryazevskaya Line. The bust was moved into a combined vestibule built into the office building of the newspaper Izvestia on the Strastnoi Boulevard of the Boulevard ring. [That might have been the case in the past but there was a bust of Pushkin on the metro platform in 2017.] When transferring between the stations it is possible to bypass the vestibule via the lyre fenced stairs leading from the middle of the columns.

The transfer point, was originally named for the three writers and poets (Alexander Pushkin, Maxim Gorky, Anton Chekhov). In 1991, the original street Ulitsa Gorkova was renamed Tverskaya, and hence the station was also given this name. The transfer point is one of the busiest in Moscow; Pushkinskaya receives a daily load of 46,770 via the vestibules, 170,000 to Tverskaya and 212,000 to the Chekhovskaya station.

From Wikipedia

Location:

GPS:

55.7650°N

37.6079°E

Depth:

51 metres (167ft)

Opened:

17 December 1975