Museum of the Malvinas War – Rio Gallegos

Museum of the Malvinas War – Rio Gallegos

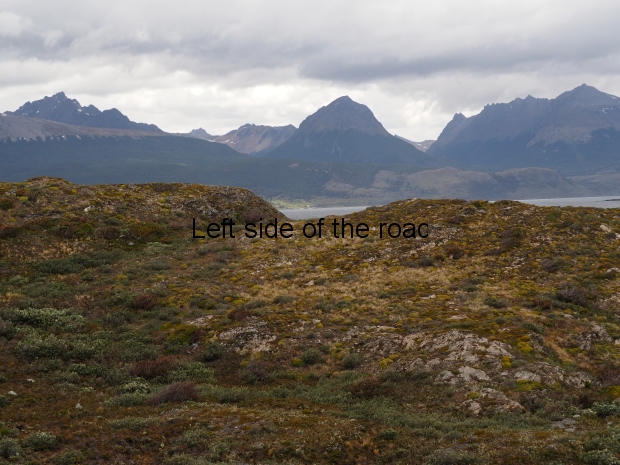

Having seen a couple of monuments to the 1982 Malvinas War in various parts of Argentina (including one in Rio Gallegos itself) I was quite interested in understanding how the country approached that war when I learnt there was a museum to the conflict in the town of Rio Gallegos. After all, Argentina lost that war but still maintains it’s claim to the islands and you are unlikely to encounter an Argentinian who doesn’t hold that idea with total enthusiasm and conviction. Museums to conflicts established by the losers are rare – for example, I have never heard of a museum in Germany about the Second World War or a museum in the United States to their failed aggression in Vietnam. With that background I was anticipating something quite unique in the town.

However I was to be disappointed as after having spent a few minutes in the small, four room museum I felt more bemused than anything else. If you have a museum to the conflict then surely it’s necessary to tell the story of why it took place and presenting the reasons for the attempt to retake the islands from the British.

But there’s no explanation at all about why the Argentinian Army was sent to the Malvinas at the beginning of April 1982. No mention of the political situation in the country at the time – even though the military dictatorship of that time fell as a result of the failure in the Malvinas. No mention of Argentina’s historical claim to the islands and no mention of how the situation stands at the moment.

In fact it’s just the opposite. It seems, according to the introduction given by the woman in charge of the museum, there was a conscious decision NOT to address these issues. But by doing so it negates the reason for the museum in the first place.

The first room appears more like a toy shop than a museum as there are glass cases full of models of the ships, aircraft and weaponry used by both sides. But this was without context. There was no mention of the importance of the Sea Harriers which were able to withstand the harsh conditions of the South Atlantic. No mention that as both sides were using some of the same weapons the Argentines were able to sink the Sheffield with an Exorcet missile as the Sheffield also used them and the ship’s defence system was confused.

Amongst the models there were a few notable absences. The Atlantic Conveyor was missing from the collection of models but it’s inclusion in the British battle fleet was crucial in acting as a decoy for the Invincible, the British command ship. Also missing were the two landing ships, the Sir Galahad and the Sir Tristram, whose bombing resulted in the greatest loss of life in a single incident for the British armed forces since World War Two.

A model of the Vulcan bomber was there but no mention of its success in damaging the runway at Puerto Argentino (known as Port Stanley by the British).

Everything in this room seemed to be aimed at sanitising the whole sordid affair of 1982.

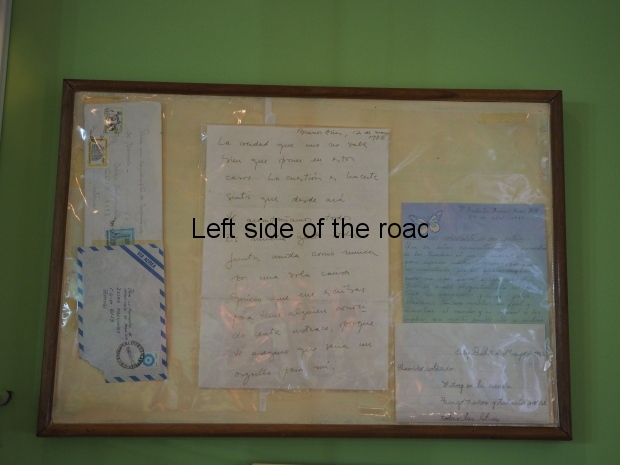

In another room there was an attempt to act on the emotions of any Argentinians who might visit the museum as there were letters from children to their fathers who were involved in the war – whether the recipients survived or not was not clear to me.

In fact it was only in the room where examples of the clothing and equipment used at the time that you get any sense that you are in a museum. Much of this equipment would bemuse children as technology has developed so much in the intervening 36 years and they wouldn’t be able to get to grips with the size of the field telephone.

This museum really isn’t worth visiting (apart from trying to work out why it’s there in the first place) and is really a lost opportunity on behalf of the Argentines. After all it could have been an opportunity to argue their case for possession of the islands, an argument few in Britain would know about.

There’s another museum in Buenos Aires which I plan to visit when I’m next there so it will be interesting to see how the matter is approached in the capital.

These museums don’t get a mention in British guidebooks but it would be churlish of me to suggest that this is a sign of censorship – conscious or unconscious.

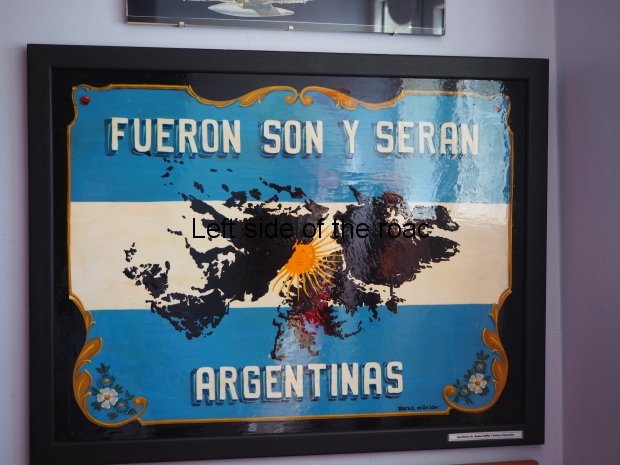

They were, are and will be Argentina

Practical Details

Museo de Guerra Malvinas Argentinas

Pasteur 72

Rio Gallegos

Open

Monday-Friday 11.00-16.30

Saturday-Sunday 10.00-16.30

Ring the bell if door closed.

GPS

S 51.62568

W 069.22165