Barrios de Pie – Enough of the price rises

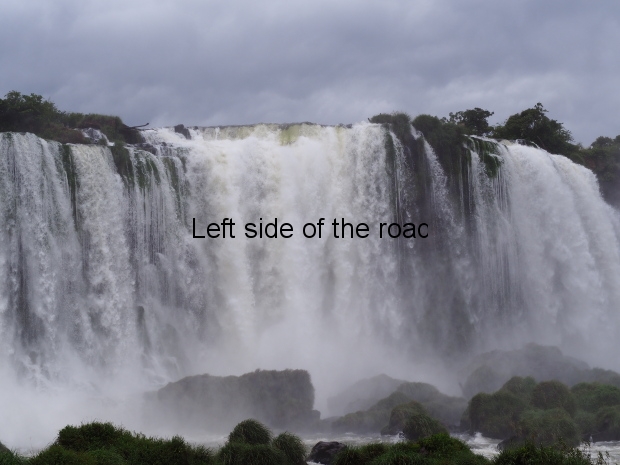

Riot police in Argentina

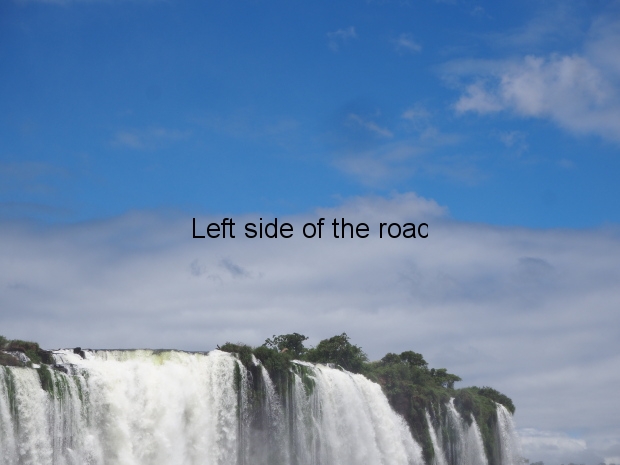

Another day in Buenos Aires another demonstration against the conditions in which the majority of the working people have to live. On my last full day in the country I encountered yet another demonstration that had formed up at the Obelisk on Avenida 9 de Julio at the normal meeting time of 12.00, midday. But whenever there’s a demonstration in Argentina the riot police aren’t that far away.

This demonstration was called by, and was formed of, the organisation ‘Barrios de Pie’. My understanding after talking to some of the stewards present is that this can be translated as ‘Neighbourhoods on the March’ or as ‘Neighbourhoods standing up’. The reason for the march was the usual – against austerity, which is increasingly having a detrimental effect on an increasing number of the poor, and the problems that are being created with an annual inflation rate (for 2018) of almost 57%.

Although all the peaceful demonstrations that have taken place in Argentina in recent months, including that against the G-20 summit at the end of November 2018, achieve no change of heart on the part of the government – who is more prepared to listen to the ‘neo-liberal’ economic strictures of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund or the Inter-American Development Bank which lead to even more privatisation and cuts in whatever remains of any social welfare provision – many Argentinians are still prepared to go into the streets to make their feelings known. (This is so different from the lack of any such activity in Britain in the ten years since finance capital caused the crisis of 2008 which has led to the ‘austerity’ of the intervening years which has seen a worsening of the living conditions of the majority of working people in the country.)

In this post I want to look at an aspect of the Argentine state activity that demonstrates that they know exactly what is happening in society. However, rather than seeking ways to ameliorate the effects on the general population what they do is to put ever more resources into efforts to protect capitalism (and their own privilege). What I want to look at here is the use of the riot police both to intimidate people on the streets at the time and to reinforce the idea of letting everyone know who is in control.

I have already written how during the G-20 bash at the end of November 2018 the Argentinian state showed that it was prepared to lock down the country’s capital for the best part of three days just to allow the world’s most insidious gangsters to feel safe as they travelled around the deserted streets and to pig out at banquets where ‘important’ decisions were made. It was reported that 20,000 police and army personnel were deployed in Buenos Aires over that weekend, all geared up in state of the art riot gear and with, no doubt, more lethal weaponry close to hand.

(It’s difficult to understand the mindset of these ‘leaders’ who now must consider such a situation being the norm at their international meetings. With them living in such a bubble – not that they weren’t in a similar bubble in the past – their statements of us ‘all being in this (i.e., austerity) together’ rings even more untrue.)

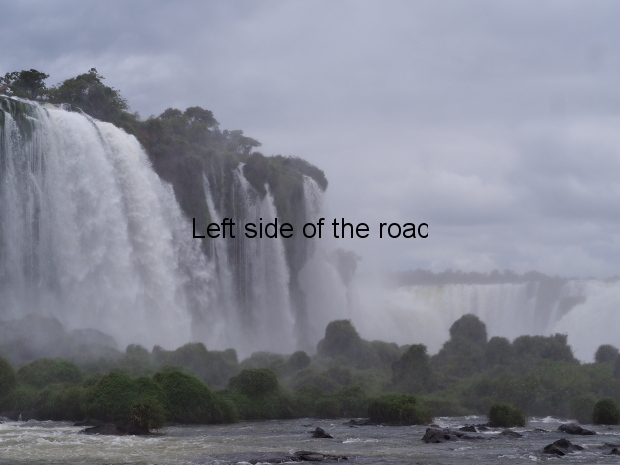

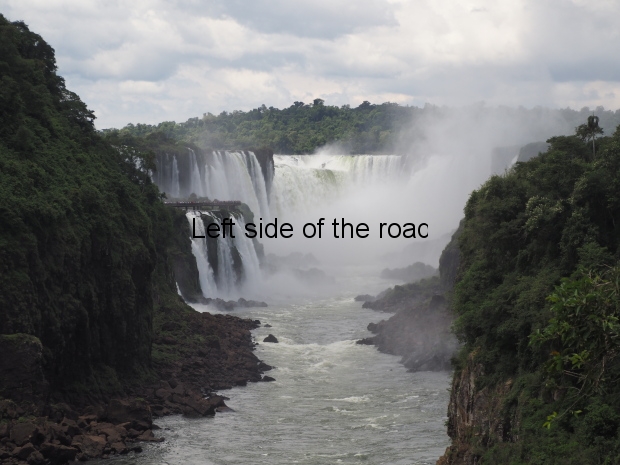

Riot Police at rear of Barrios de Pie demonstration

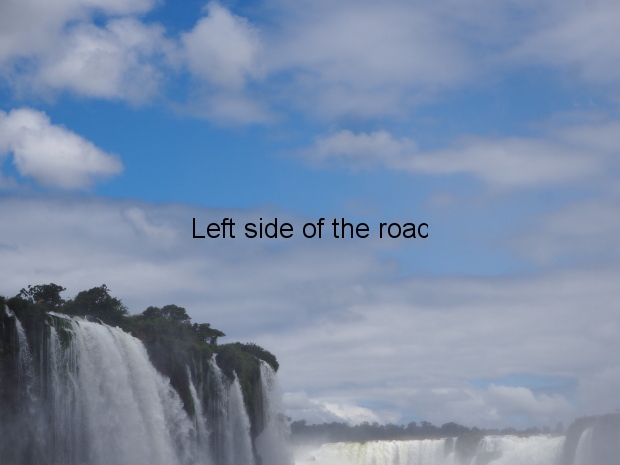

I came to the ‘Barrios de Pie’ demonstration by chance at the Obelisk just after it had moved off and what struck me was the number of fully kitted out riot police still in the area and preparing to march at the side of the rear of the march. It wasn’t a surprise to see them there as they had been in evidence at the first demonstration I was to experience on my first Monday in the country but it made me think of their role in Argentinian society.

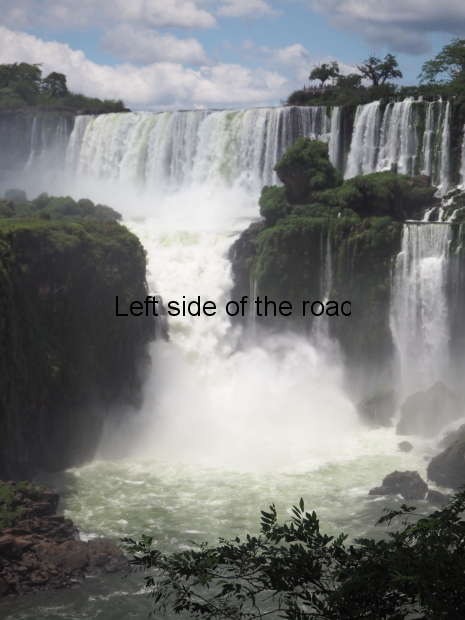

Riot Police escorting head of demonstration

Argentina is not unique in having riot police prepared to appear on the streets when workers seek to make their grievances known to the rest of the population but I’ve now had the opportunity to see how it works on a number of occasions. This approach is slightly different in a country such as Britain where the state places a few, less intimidating police on the streets but with the ‘iron fist’ prepared to appear on the scene within minutes if called upon.

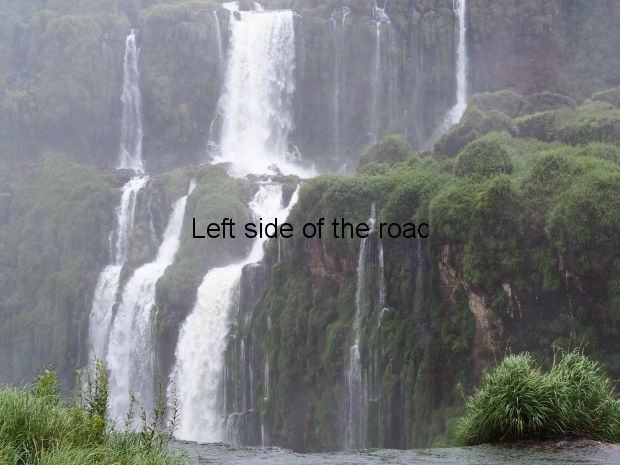

The march and the Obelisk

The issue in Argentina (and probably in most Latin American countries, more than likely due to the continent’s history of military dictatorship) is that the armoured police are there from the start – even though they would know that in such circumstances it only takes a slight misunderstanding for matters to escalate (perhaps the reason they are placed there in the first place). And many others would be on call if a peaceful march was to take a violent turn.

Porteños – the citizens of Buenos Aires – are also constantly reminded of the preparedness of the state to react to any civil disturbance by the number of ‘vallas’ (large, black, metal barriers) that are dotted around different parts of the city centre. I wrote about these in the posts in reference to the G-20 of November last year. The vast majority of – it must be – hundreds of new ‘vallas’ have been removed from the streets and now in some unknown (to me) storage facility, ready for any eventuality (if they aren’t already on a ship mid-Atlantic heading to Osaka, Japan, the location of the next G-20 at the end of June 2019). However, there are always some stacked in a corner near the Casa Rosada and, strangely, the Cathedral at the top end of Plaza de Mayo seems to have a screen of ‘vallas’ in a semi-permanent state.

Vallas ready for use at the Casa Rosada

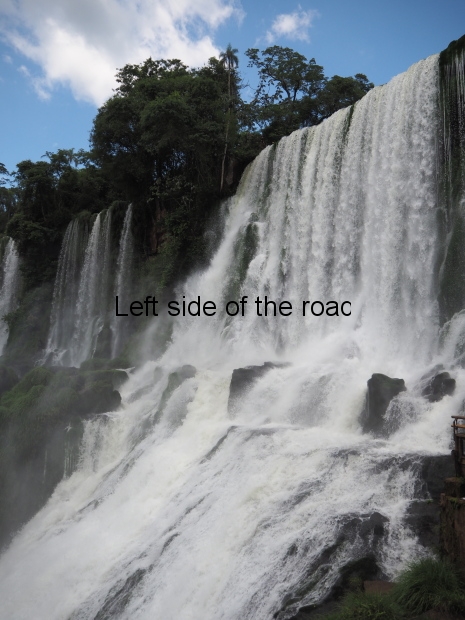

It’s the heavy hand at the beginning which shows the contempt the state has for the people’s right to demonstrate. They try to frighten people from coming out in the first place and then by escorting the march along its short route (from the Obelisk to the Casa Rosa is much less than a kilometre) they are reinforcing the message.

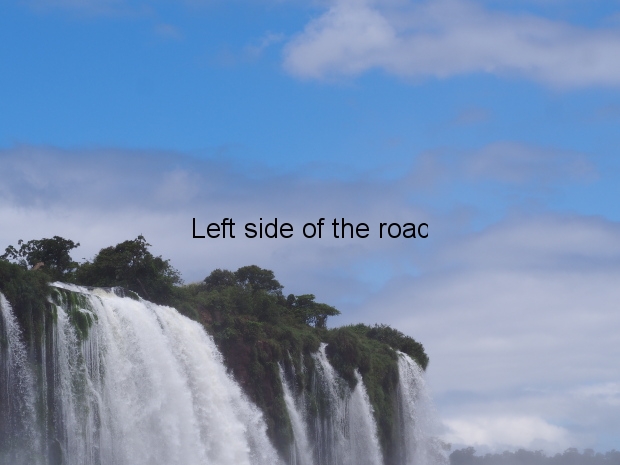

The marchers from the ‘Barios de Pie’ understood this well and knew what the state was attempting and the demonstration was very heavily stewarded, many men and women walking between the police and the general body of the march. And they ‘policed’ their own people. That Thursday was very hot and once the march reached the top end of the Plaza de Mayo (the square in front of the Casa Rosa – the Presidential Palace) a few women, a number of them with babes in arms, moved out of the march to seek shade from the few trees at the top end of the square. This caused a couple of the stewards to come over and ask them to re-join the group as ‘they didn’t want trouble from the police’.

Stewards – in blue vests – between marchers and Riot Police

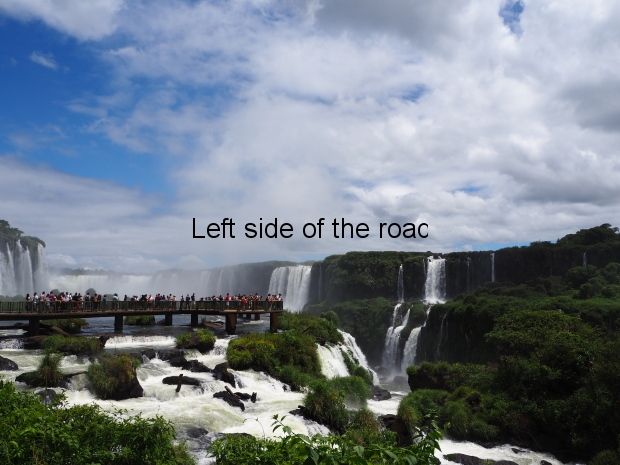

I wasn’t aware of the idea that the square was a no-go area before that incident. And that knowledge explained the manoeuvre of the police who had been escorting the march at the front into context. As the lead marchers turned the corner from Avenida Peña into Avenida Bolivar the police peeled off and stood in a line between the marchers and the Casa Rosa. It wasn’t a substantial line and they would have had problems holding it if there was a concerted effort to enter the square, their stand was more symbolic, wordlessly making the challenge ‘pass if you dare’.

Riot Police deploying at top of Paza de Mayo

But there was no chance of that happening. There were perhaps around a couple of thousand people on the march but a not inconsiderable number of them were mothers with very young children. There was no way such a group of people would carry out a suicide attack to get into a square which would achieve nothing even if they were successful. This was not a group of people such as the present day ‘gilets jaunes – yellow jackets’ in France who are expressing their anger at the effects of government policies on living standards and prepared to face the flunkies of the capitalist state.

Riot Police between marchers and Plaza de Mayo

After spending some time at the top of the square the march moved just a couple hundred of metres to get as close as possible as it could to the Casa Rosada – the palace has two sets of very high yet thin metal fences from the centre of the Plaza de Mayo to the entrance of the building – the second is only closed off when there’s some anti-government activity in the vicinity, in the process disrupting the traffic as the roads are also blocked. Such a fence would be no deterrent to a determined force as they would bend easily if enough organised force was used to pull them down. Just in case of such an unlikely eventuality there were a number of police inside the grounds of the Casa Rosada ready to react if called upon to do so.

Riot Police inside first fence of the Casa Rosada

But once here the march became quiet after making quite a lot of noise with the drums and whistles when on the move. And it stayed there for a long time, with me not quite understanding why. They were being totally ignored by the authorities in the palace and staying in the street just meant that their own people were being cooked at the hottest time of the day.

Matters eventually became much more relaxed. People started to drift into the shade of the trees in the square, the police totally ignoring this transgression, and some of them opened up their bags and had a picnic on the grass – on all the demonstration to which I’ve been a witness, including the big anti-G-20 march – many people came with some sort of food and drink. Others queued up at the public water fountain close to the fence. They had left the demonstration but hadn’t drifted off as is normally the case in such situations and they were ready to be called back once the decision to move was made.

Even the police became more relaxed, first resting their shields on the ground which was soon followed by them removing their helmets which changed the whole general feeling of the situation, any tension being dissipated. These movements were all organised and it seems that the Argentinian police are organised in squads of seven or eight as that was how they moved. As mentioned in the post on the demonstration in Buenos Aires back in November there are women in the riot police and here there seemed to be a squad made up of only women – all of them with long hair tied into pony tails – which indicates that there was no serious thought of violence on the side of the authorities as that long hair would have made them extremely vulnerable in the event of a flare up.

Whilst I was watching not very much happening I wondered what these young riot police thought of their role in the state machine. I don’t know if the state had decided to protect their salaries from the force of 57% a year inflation but even if it did all these officers would have known people who would have had no such protection. 2018 wasn’t a good year for Argentinians and the vast majority would have ended the year worse than they started. Yet these people were still ready to stand between an angry population and the state and its capitalist supporters.

In the past the police have not shown restraint when let loose on anti-government protesters, there being a number of deaths under ‘democratic’ governments, at least three in the final months of 2018, although on no occasion did I witness such an attack. Whether that reflects a change in the policy of the state which realises that such an approach doesn’t stop people from going on the streets or whether the state is not sure of the total loyalty of the police and asking them to attack people with widely accepted and recognisable grievances might eventually backfire I can’t say.

The march along Avenida Peña

However, these forces of ‘law and order’ are a vital for the existence of the capitalist state and having the riot police out at least a couple of times each week in Buenos Aires alone must eventually get some of them to question what their role is in Argentinian society.

Or perhaps not. Their predecessors in the 1970s were either active participants or passive onlookers to the ‘disappearance’ and murder of more than 30,000 Argentinian citizens – the very people who they pledge to protect when they take their oath on becoming police officers.

(The more observant of my readers might have noticed that both Evita and Che appear on the lead banner of the ‘Barrios de Pie’. I hope to address the issue of Evita and the way she is considered in present day Argentina in a post in the not too distant future.)