Caracol

Caracol – Belize

Location

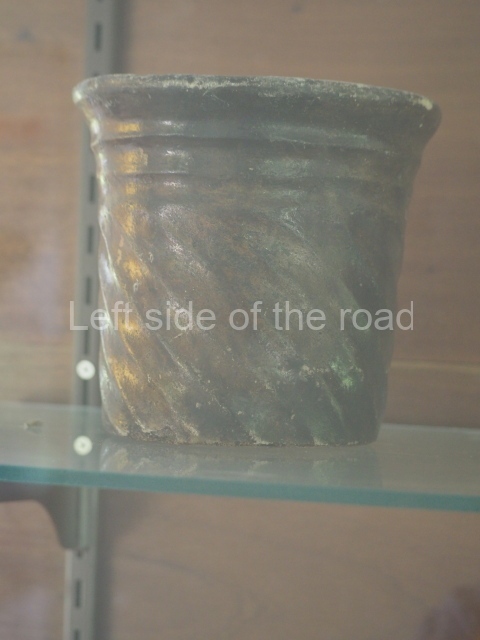

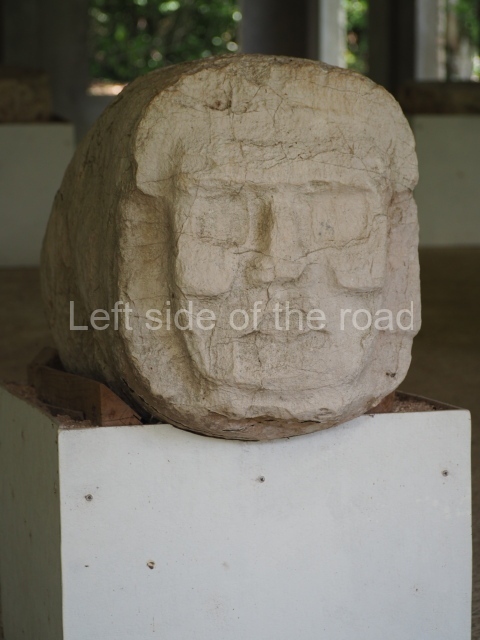

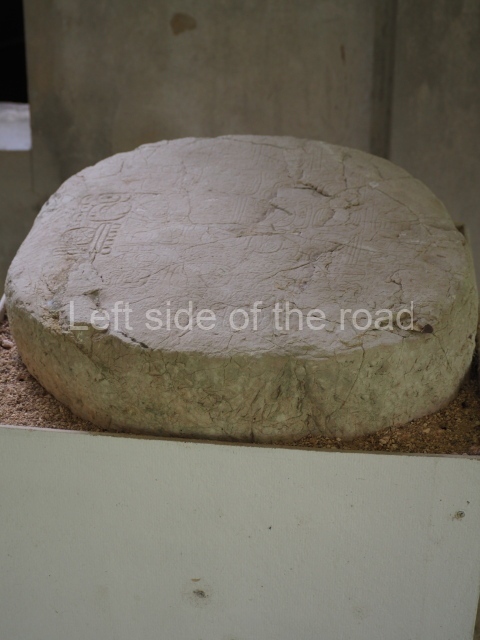

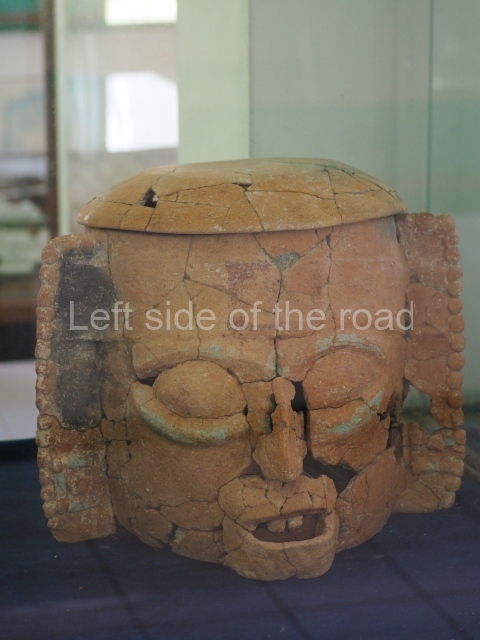

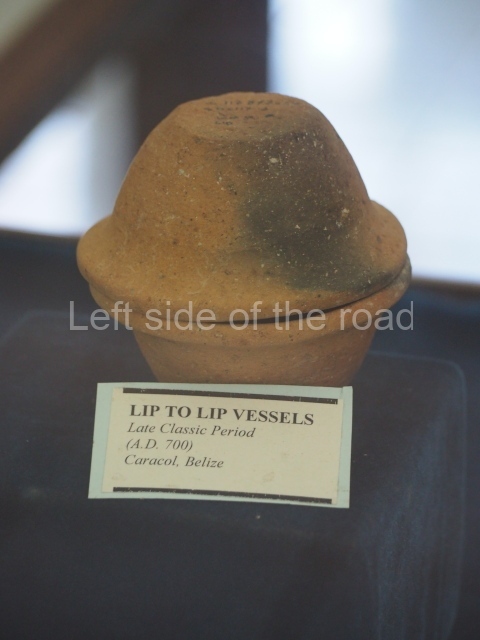

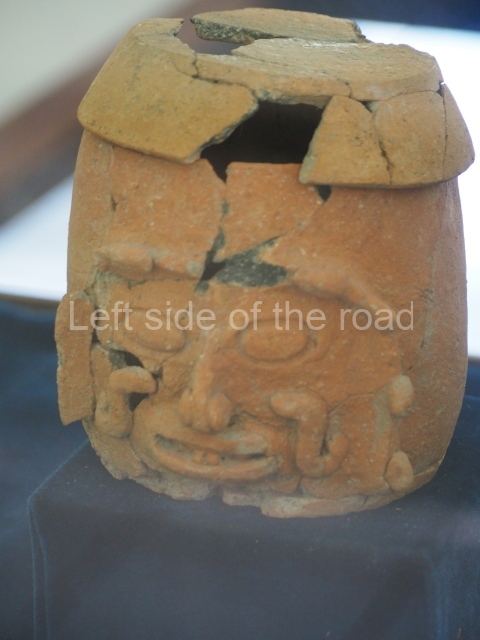

This is the largest archaeological site in Belize and, during the Classic era, it was also the largest urban centre in the region. It was thus named by the British archaeologist A H Anderson due to the abundance of snails [caracoles in Spanish] found on the clay paths amid the ruins. The site is situated on the west face of the Maya Mountains, in the Chiquibul forestry reserve surrounded by the Chiquibul and Macal rivers, in an asymmetrical mountainous area some 500 m above sea level. Due to the wealth of the natural surroundings and its strategic position between the central lowlands and the Caribbean coast, it became one of the most important urban settlements in the Maya area. Over 60 km of sacbeob or Maya causeways have been identified further inland, which were clearly used for trading and communication purposes. This great city and the outlying settlements are thought to have had a combined population of over 100,000 inhabitants. Caracol is situated approximately 120 km from San Ignacio, in the Cayo district. There are two accesses from the Western Highway, with signs indicating the turn-off to the site. To reach the site from the twin towns of San Ignacio and Santa Elena, take the Cristo Rey road via the Yucatec Maya village of San Antonio and then switch to the Chiquibul road. If you take the Western Highway from the capital Belmopan, turn on to the Chiquibul road when you reach Georgeville. This road, which is still not entirely paved, crosses the Mountain Pine Ridge Reserve and leads to the Douglas D’Silva Forest Station in the Rio Frio Caves area. At this point visitors are obliged to report to the control post for escort to the archaeological site as the access route passes through a British military zone deep in the heart of the Maya Mountains. The road to Caracol from the forest station is in fairly good repair and takes you right to the archaeological park. The site has a visitor centre and rest rooms, but there is no food or drink. There is also a simple but interesting site museum that houses a ball court marker with a hieroglyphic inscription, various typical incense burners from the region and other ceramic objects found at the site. A scale model provides visitors with a general idea of the city at a glance and there are also explanatory panels about the archaeological explorations in the area.

History of the explorations

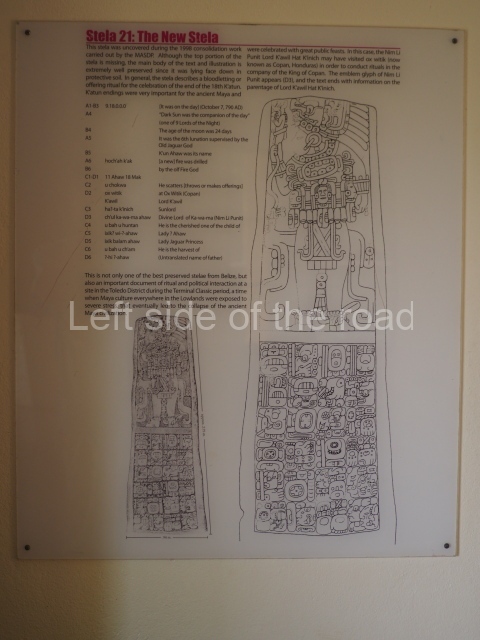

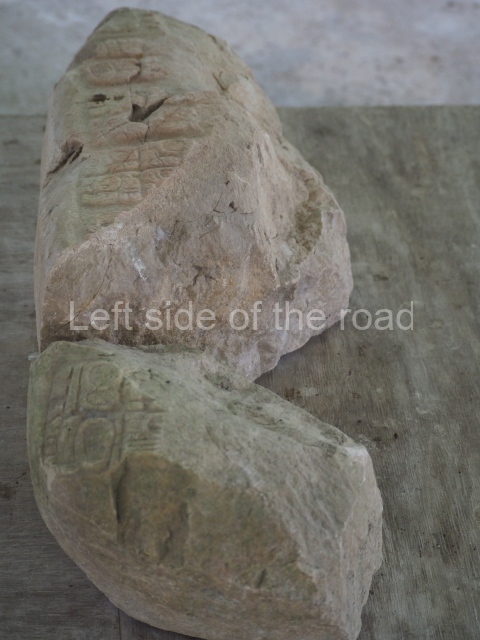

The site was identified in 1939 by Rosa Mai, a logger looking for fine wood. That same year the archaeologist A H Anderson visited the area and christened it Caracol. In the 1950s, the archaeologist Linton Satterthwaite from the University of Pennsylvania conducted excavations at the site to rescue various monuments sculpted in stone. In 1954 the first archaeological commissioner for Belize, Anderson, carried out new excavations and located the funerary chamber, B2. In 1977 the museum of the University of Pennsylvania sent Carl Beetz to finish the work begun by Satterthwaite. A few years later, in 1978, Elizabeth Graham sent a team to rescue monument 21, currently on display at the museum in Belmopan. That same year and the following year, Paul Healy from Trent University investigated the artificial terraces around the site. In 1985 the archaeologists Diane and Arlen Chase from the University of Central Florida embarked on a series of ongoing extensive excavations. Similarly, in recent years the Belize Institute of Archaeology directed by Jaime Awe has consolidated the Caana monumental structure and various stucco masks, such as those on Building B5, have been protected with replicas.

Pre-Hispanic history

The recent discoveries at Caracol have altered our former knowledge of the site. Explorations have demonstrated that the area was densely populated and that the terrain was modified with terraces for cultivation and habitation purposes; the outlying area was connected to the ceremonial centre via a large network of roads built with stone and mortar. Intensive farming provided the local inhabitants an agricultural surplus that favoured the development of a powerful kingdom on a par with Tikal, Calakmul and other smaller sites such as Ucanal, Naranjo and B’ital. The political links with these powers in the Maya lowlands turned Caracol into a key player in the diplomatic and military manoeuvres of the Classic era.

Epigraphic studies have revealed a long dynastic sequence comprising 14 kul ahaw or ‘divine lords’, commencing in the mid-4th century with a figure called Te’ Kab’ Chaac or ‘Tree Branch Rain God’, thought to be the founder of the Caracol dynasty. It would appear that the original name of the city was Oxwitza, ‘Place of Three Hills’. The ruler Ahaw ‘Snail Knot’ left an impressive monumental legacy. The 2-katun (40-year) reign of his brother K’an II, the fifth ruler and perhaps the most successful chief of Caracol, propitiated the development of outlying centres connected to the main centre by a large network of roads. His mother, Lady B’atz Ek’, also played an active role in politics and she is thought to be buried inside Pyramid B19 on the Caana platform.

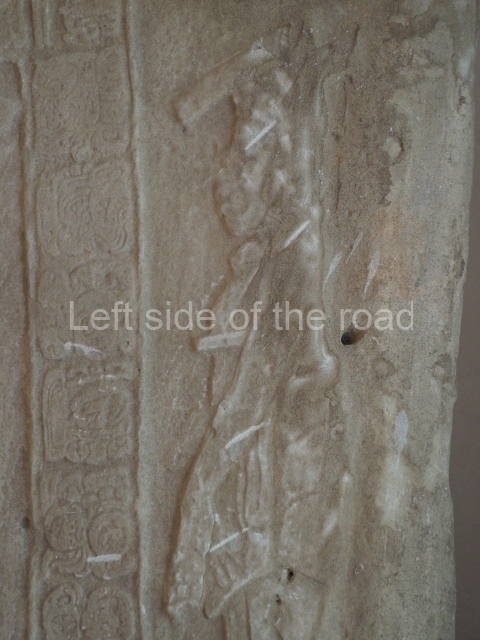

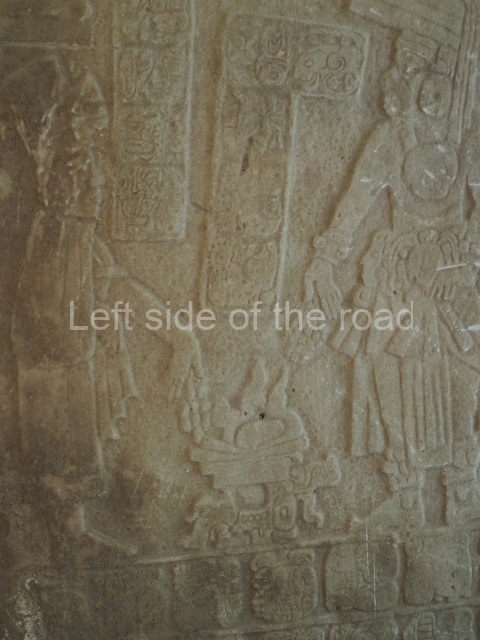

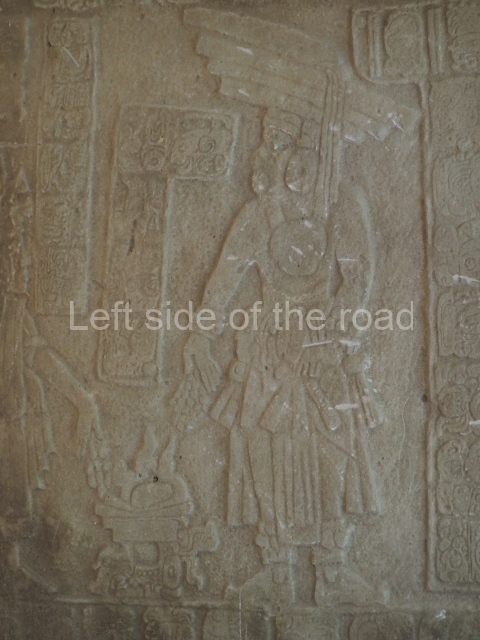

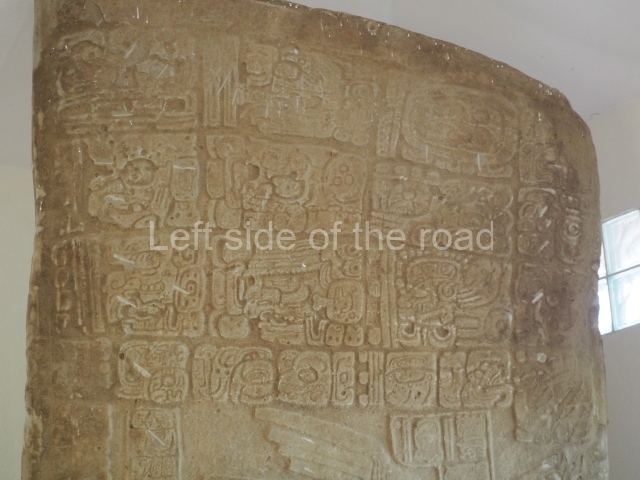

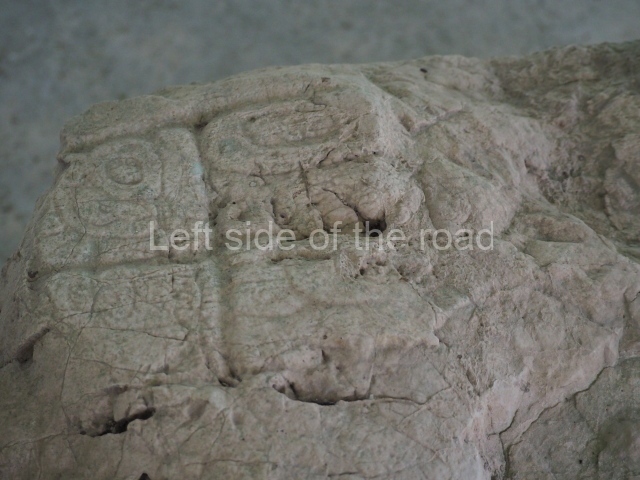

Other historical data recorded in the stone hieroglyphs are the fall of Caracol as a result of a war with its rival Naranjo, after which it remained in a kind of hiatus lasting 118 years until AD 798, when the local nobility revived their traditions with K’inich Joy K’awil, the ninth figure in line to the throne of Caracol, who captured the ‘divine lords’ of Ucanal and B’ital. This event is recorded on Altar 23 situated at the centre of the site in a provisional place to protect it and other sculptures from the elements. The monuments of the subsequent rulers reveal common thematic and stylistic innovations during the Terminal Classic period, such as shared scenes in which the ruler converses or performs ceremonies in the company of another high ranking figure. According to the epigraphers, this marked a change in the autocratic power to meet new circumstances in which the rulers had to negotiate their position with other leading members of the nobility, either local or foreign, whose power equalled or exceeded their own.

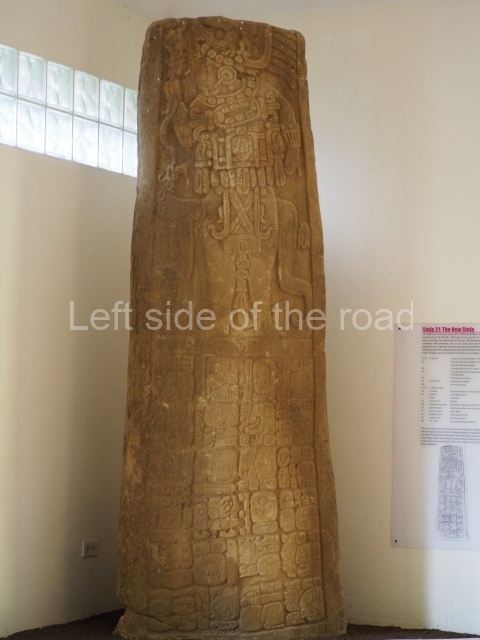

Other important sites in the region ruled by Caracol are La Rejolla, Hatzcap Ceel, Caledonia and Mountain Cow. Caracol was the largest state in the region. By the end of the Maya hiatus, it probably had a larger population than Tikal. The latest inscription at Caracol can be found on Stela 10 and corresponds to the Maya date 10.1.10.0.0 (AD 859). There are no known monuments after this date that mention the heroic feats of the rulling elite, although the destroyed city shows evidence of having continued to be occupied for some time.

Site description

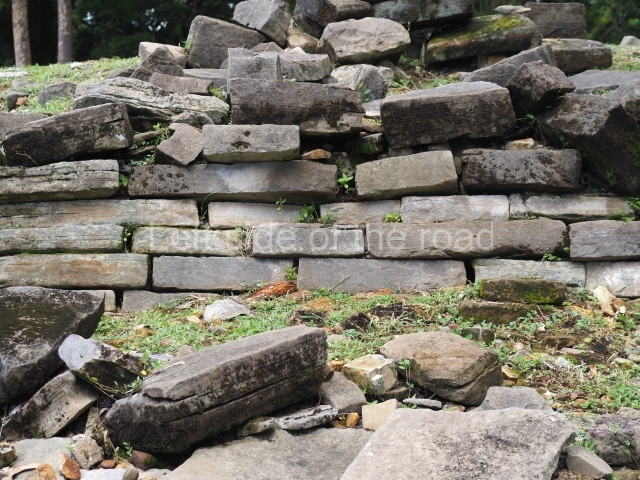

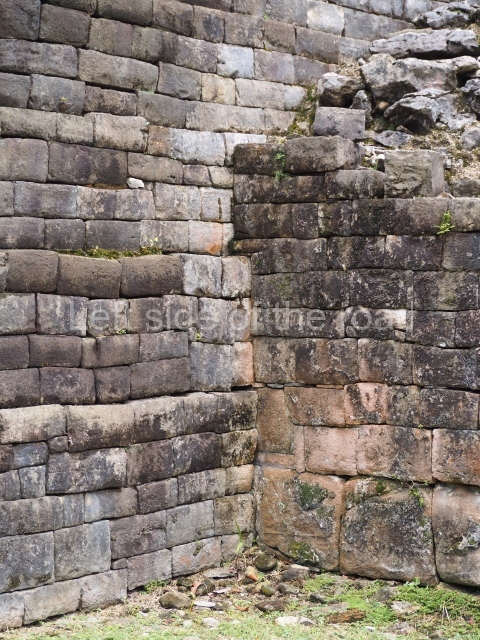

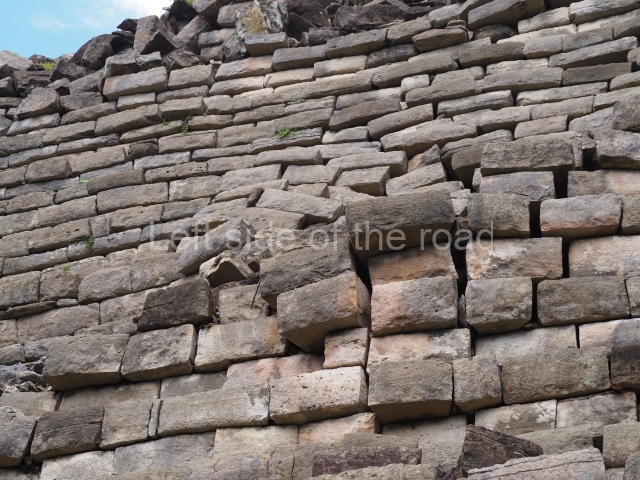

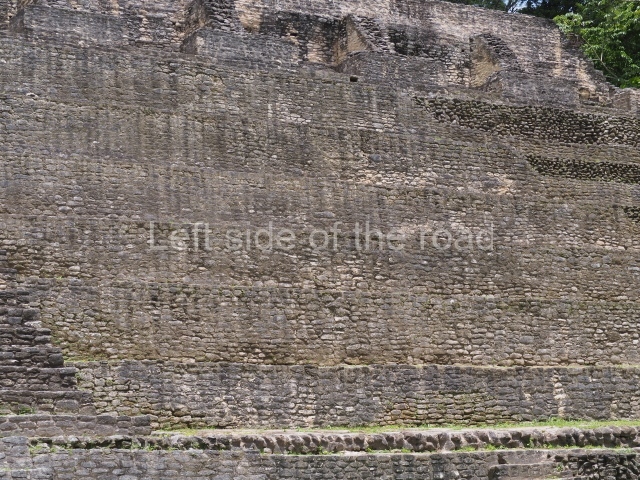

The central area of the site occupies a surface area of 3 sq km. The site reveals great urban growth between AD 550 and 700. During the Late Classic important changes occurred: increased building activity, strong population growth and the development of farming based on a system of raised terraces. At Caracol 4,400 structures have been identified and mapped in an area of 4 sq km. The site is situated 75 km in a straight line from Tikal and 45 km from Naranjo, in Guatemala. The area has a complex network of interconnected roads with various outlying sites around the central area. Several architectural structures at the site have been consolidated and a large number of sculptural monuments have been recovered, providing important historical data about the rulers of this great city.

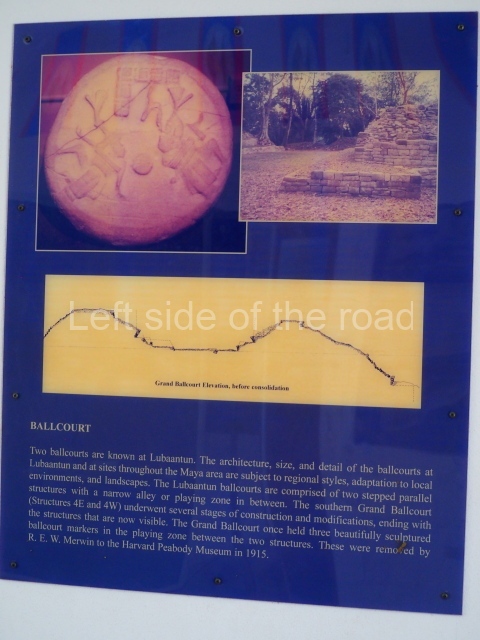

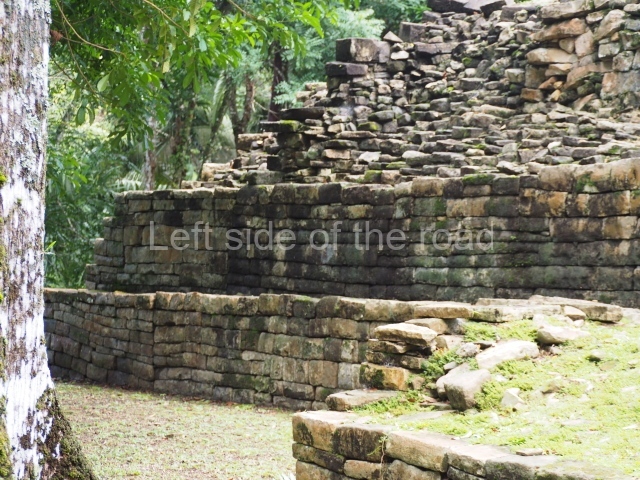

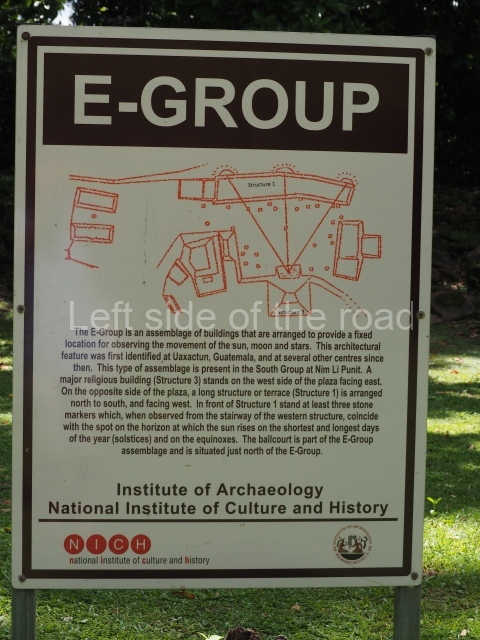

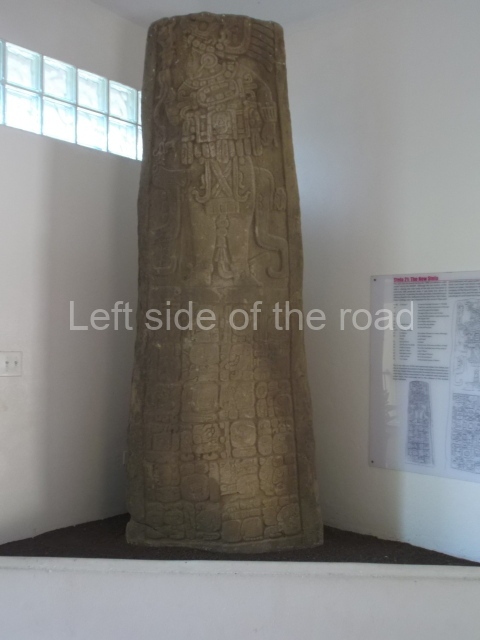

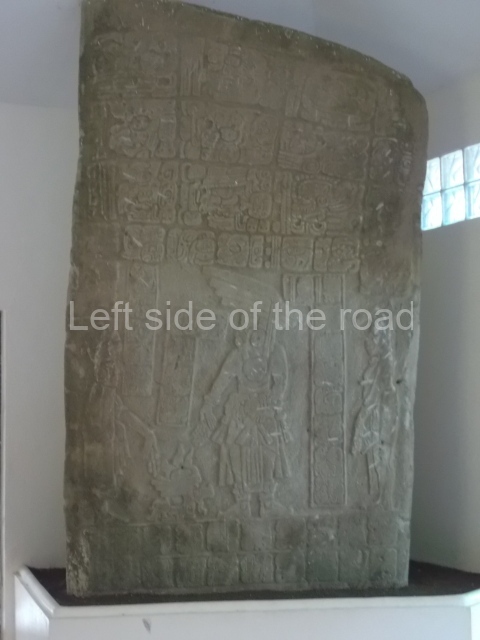

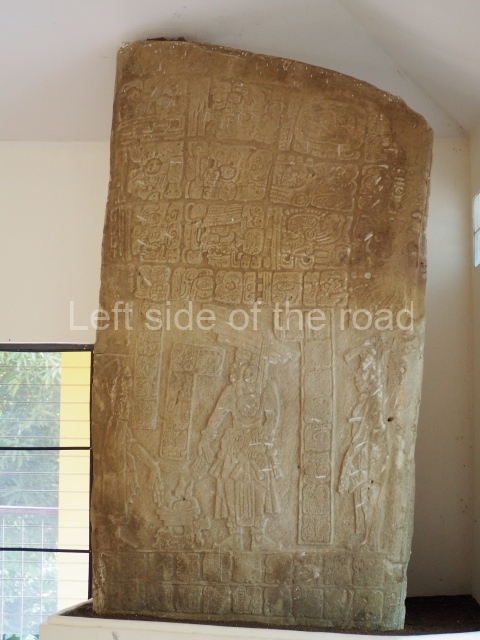

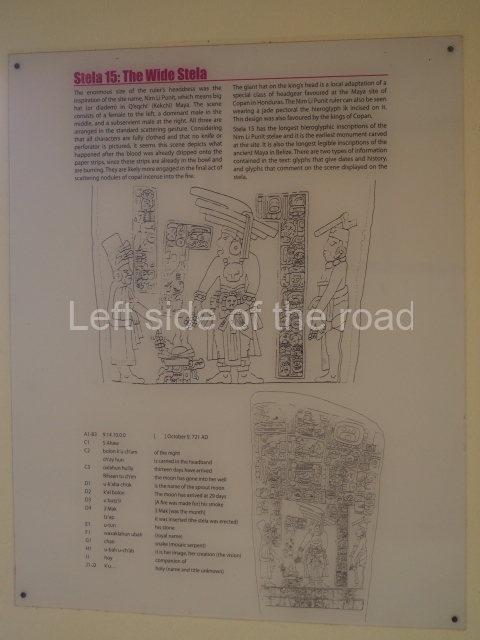

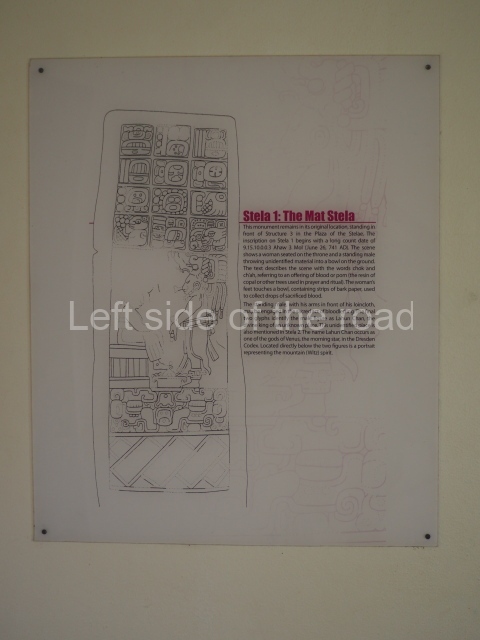

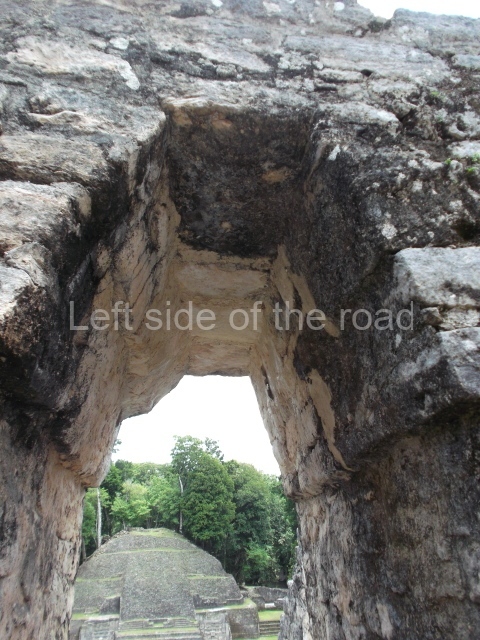

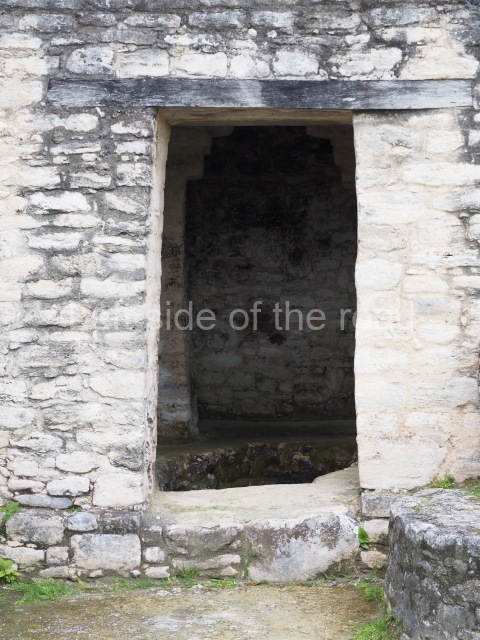

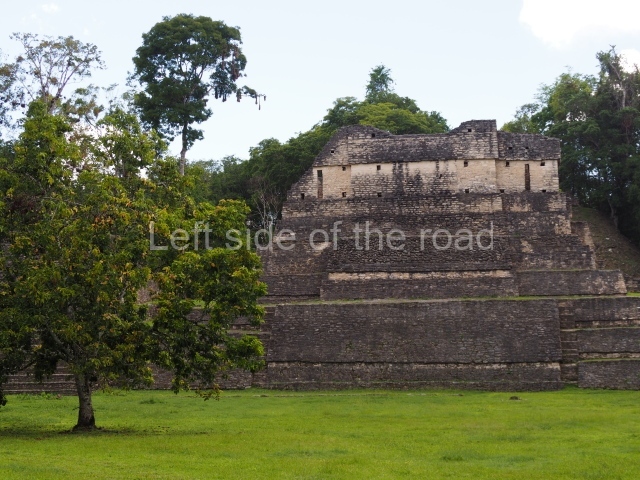

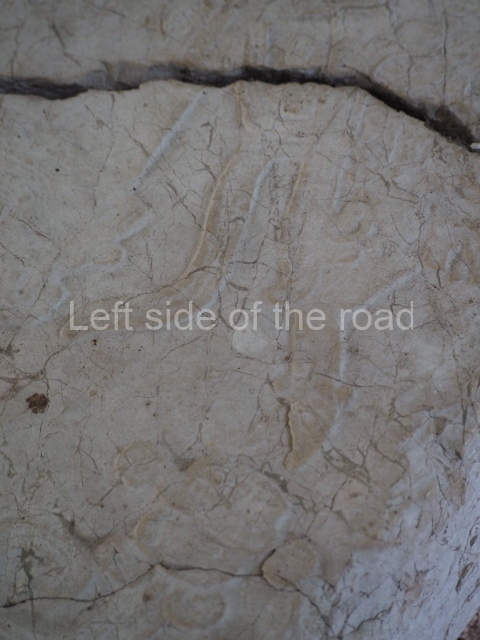

Visitors enter the area via Group A, which is situated in the west section and comprises more than 12 structures around an enclosed plaza. Interesting to note is the presence of an E-Group or observatory. These structures were used for establishing the points of the solstices and equinoxes, celestial observations closely tied to farming cycles: ploughing, sowing and harvesting. At the centre of the group is a large elongated construction known as Building A6 or ‘Wooden Lintel’. This building displays a long building sequence from the Late Preclassic to the end of the Classic period. At the top of structure A2, on the west side of the plaza, Stela 22 (AD 633) was found; it contains the longest hieroglyphic inscription known in Belize to date. Situated on the south side of this same group is Ball Court A. Floor marker 21 was identified at the centre of the court and holds special significance in the history of Caracol as it records the victories over the ruling lineage of Tikal in April AD 562. The marker was probably dedicated to the accession of the fifth ruler of Caracol, Lord K’an II, commemorating his military victory over his old rival Naranjo in AD 631.

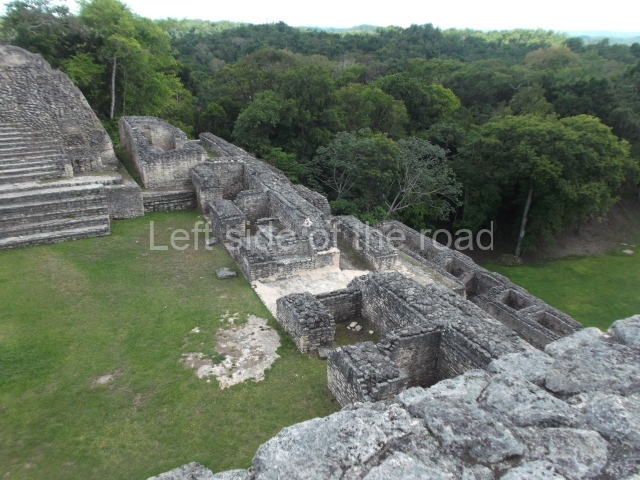

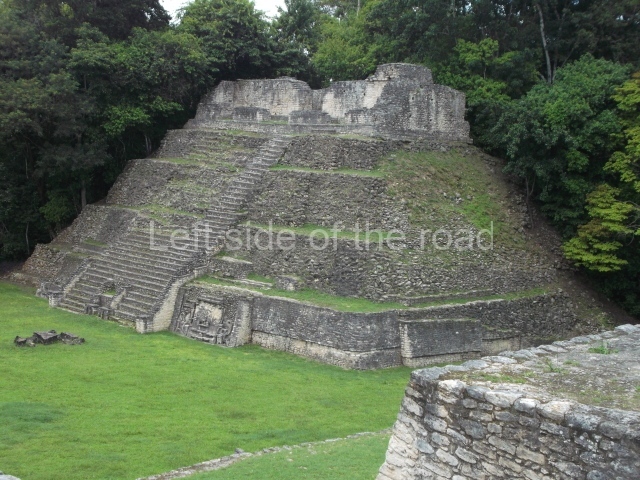

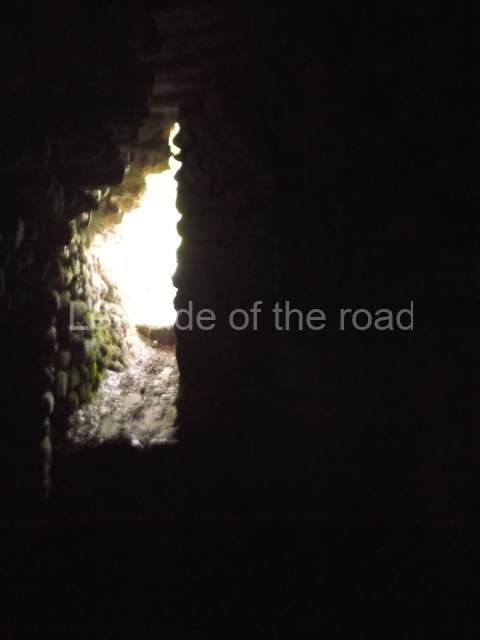

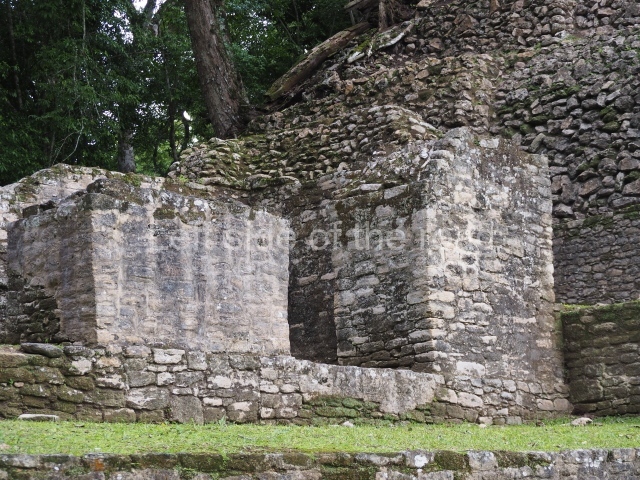

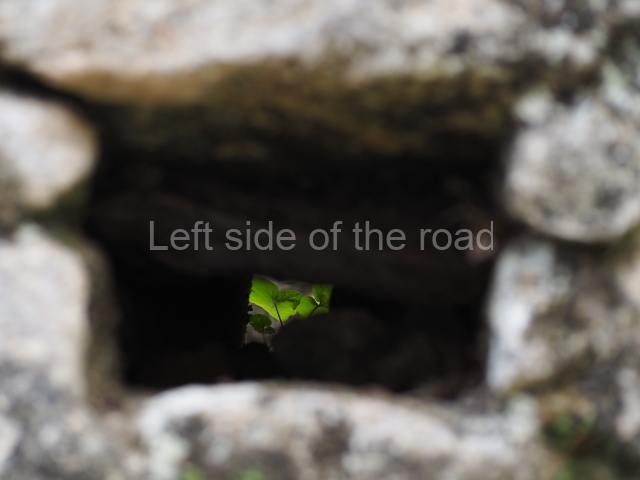

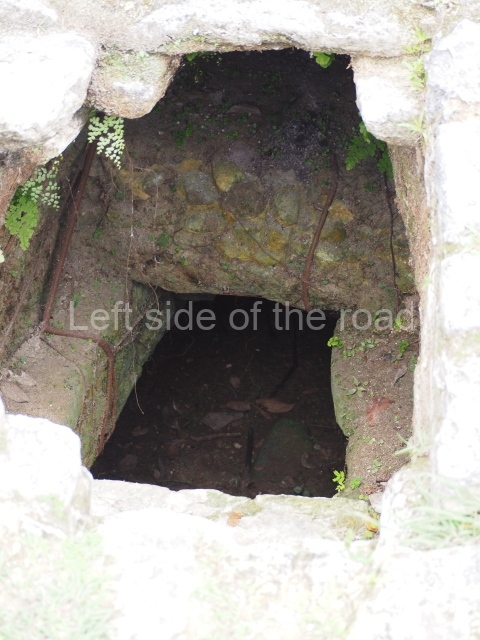

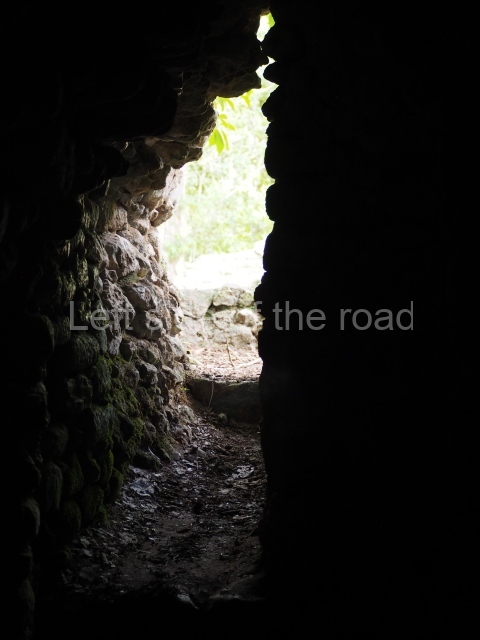

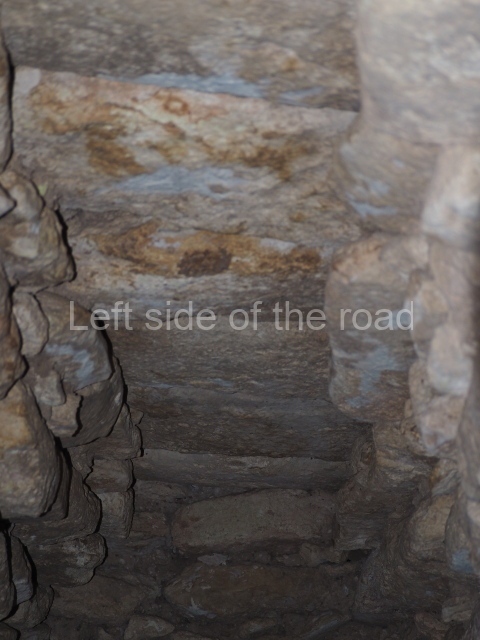

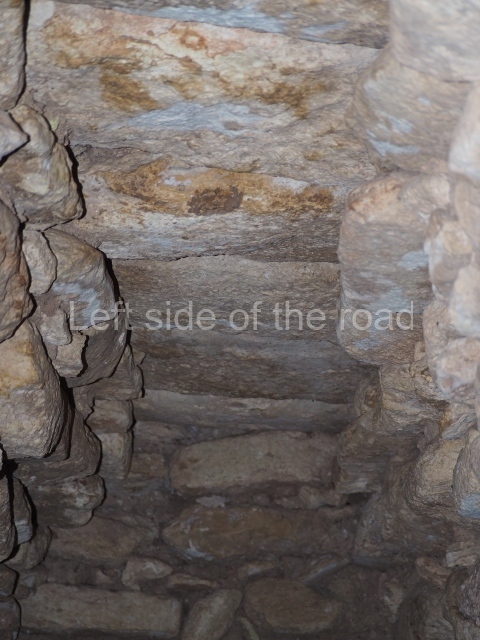

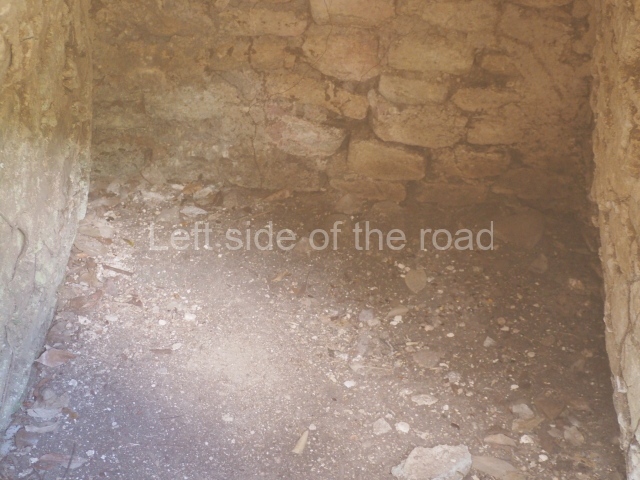

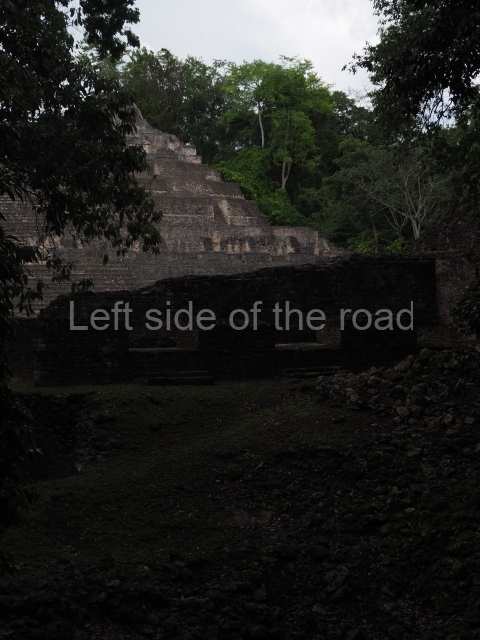

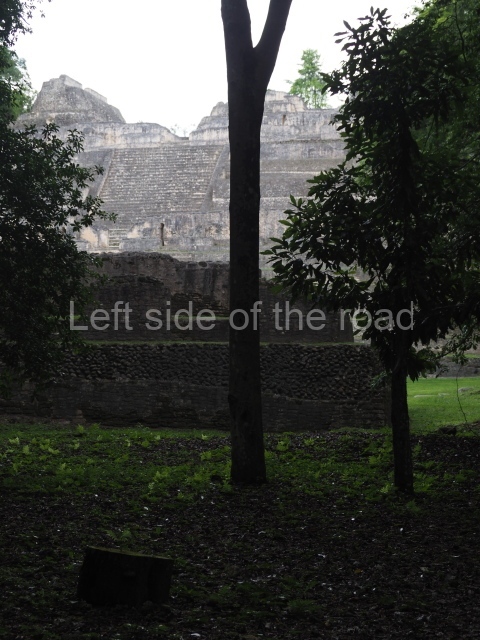

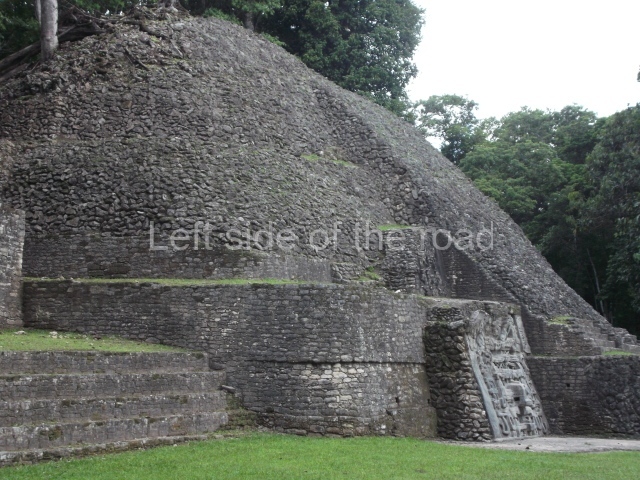

Continuing to the east we arrive at the central acropolis, the Late Classic residential and funerary complex that accommodated the ruling class of this period. Situated at the south end is another large residential group, the south acropolis, which delimits the south side of this central area of the site. Between the two acropolises is a large reservoir, which must have supplied the residential complexes with water. Situated at Group B, in the north-east section of the site, is the largest architectural complex and Caracol’s greatest pyramid, which the archaeologists christened Caana, meaning ‘Sky Place’. This vast construction that stands over 43 m high and dominates Plaza B is the most complex single building on the site and displays multifunctional architecture comprising administrative, residential, funerary and religious spaces. Its main facade has been cleared of rubble and consolidated. Several constructions were built on top of this great pyramid, around a large enclosed court. The buildings in a triadic arrangement on the top reveal the remains of stucco masks and contain vaulted funerary chambers. The massive pyramid also contains several buried constructions, the oldest one dating from around 200 BC. Opposite the Caana building, on the south side of the plaza, stands Building B5. Visible at the sides of the central stairway of this temple are the remains of stucco masks representing the ‘Earth Monster’ or Witz and other deities such as the rain god. These superimposed masks reveal two building phases and provide us with an idea of the profuse decoration on Maya constructions. Also situated in this section is Ball Court B, where four markers have been identified; the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the markers record the accession to the throne of K’inich Joy K’awil, one of the last rulers of the site, in AD 799. Group B also contains a fine masonry construction used as a reservoir. Situated in the north-east area of Group B are structures B2i to B26, identified as the ‘neighbourhood’. This area accommodates two palaces and residential areas corresponding to the Late Classic period (AD 800). There are other residential groups nearby but these are not open to the public

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp248-254.

Caracol

- Group A; 2. Structure A2; 3. Structure A6; 4. Ball Court A; 5. Struture A13; 6. Central Acropolis; 7. South Acropolis; 8. Group B; 9. Caana; 10. Ball Court B; 11. Building B5; 12. Structures B21 to B26.

How to get there:

From San Ignacio. Not easy – if you don’t have your own transport. The only other way is to book on a tour from one of the many agencies in San Ignacio – but they only do trips if they have at least two people. Cost is B$250. This is an all day affair, taking in visits to some of the natural highlights, Price includes lunch and entrance to the site.

GPS:

16d 45’50”N

89d 07’03”W

Entrance:

B$15