More on the Maya

Iximche – Tecpán

Location

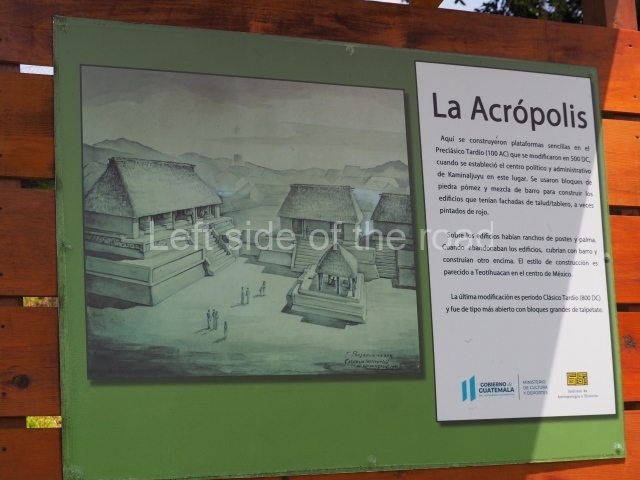

The archaeological site is situated 90 km from Guatemala city, in the department of Chimaltenango, and 5 km from the town of Tecpán. It occupies an upland area some 2,260 m above sea level, and the predominant climate is therefore mild to cold. The Iximche citadel sits atop a hill called Ratzamut, surrounded by deep ravines. Coniferous forests, principally pine and cypress, are the predominant vegetation. There is usually a cool wind blowing which on striking the trees produces a pleasant, relaxing sound. Iximche is a Caqchikel word meaning ‘place of maize trees’, the predominant species in the central Guatemalan Highlands. This city was the capital of the Caqchikel kingdom between the late 15th and early 16th centuries. It was founded in 1470, after the Caqchikel Maya, the former allies of the K’iche’s, were expelled from their land as a result of various internal conflicts. In keeping with the Postclassic custom, they sought a base on a high plateau with defensive properties, in the middle of a fertile crop-growing region populated with woodlands. This base soon gained a larger population.

Pre-Hispanic history

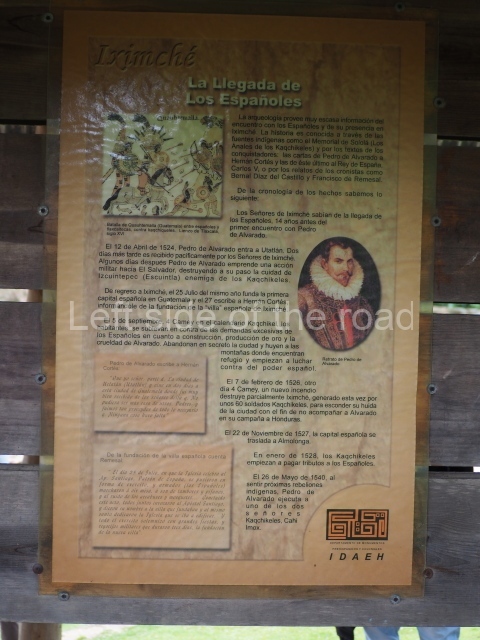

The prosperity of Iximche was relatively short, lasting only 60 years, because despite its territorial expansion, particularly towards the rich resources on the south coast of Guatemala, the Spanish Conquest led to its abandonment and destruction. The Spaniards were initially received as allies by the Caqchikel monarchs Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox, but the alliance was short lived and the settlers left the city, which was subsequently burned and abandoned by the Spaniards. It was here that the first colonial city in Guatemala was founded, called Santiago de Guatemala, on 25 July 1524. On subsequently being abandoned, the city was transferred on three occasions to different sites, eventually ending up at the present-day Guatemala City, where it took the name of La Nueva Guatemala de la Asuncion.

Site description

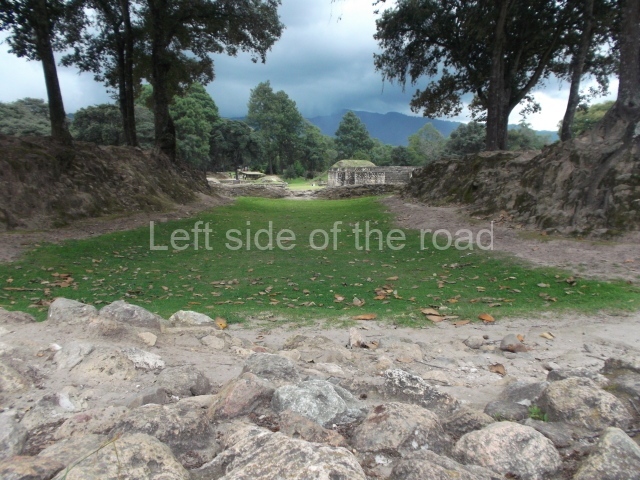

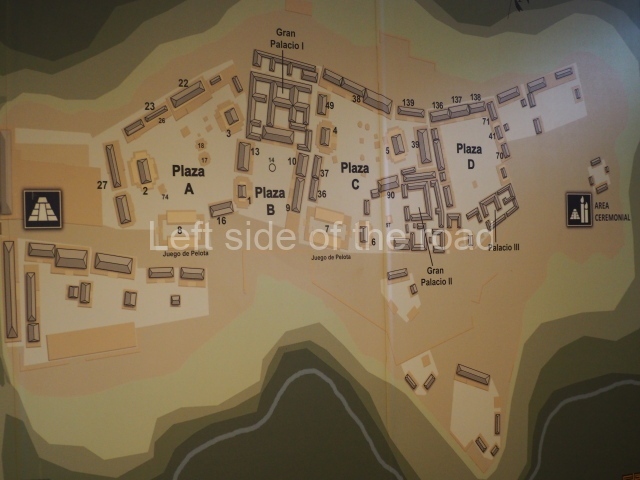

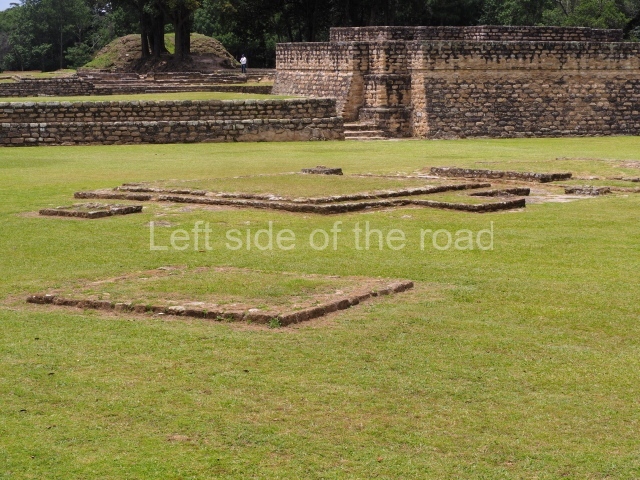

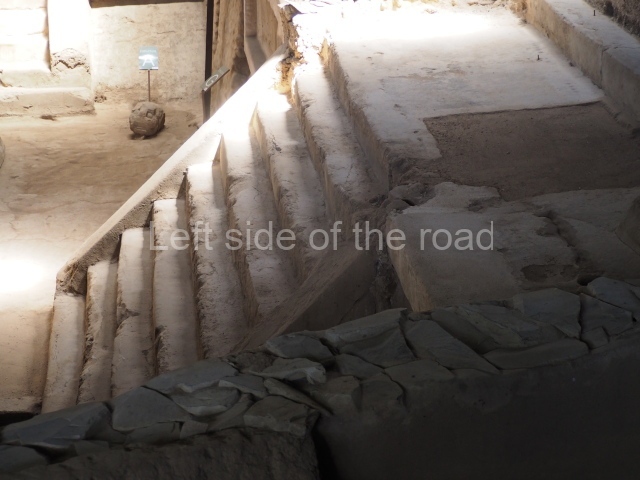

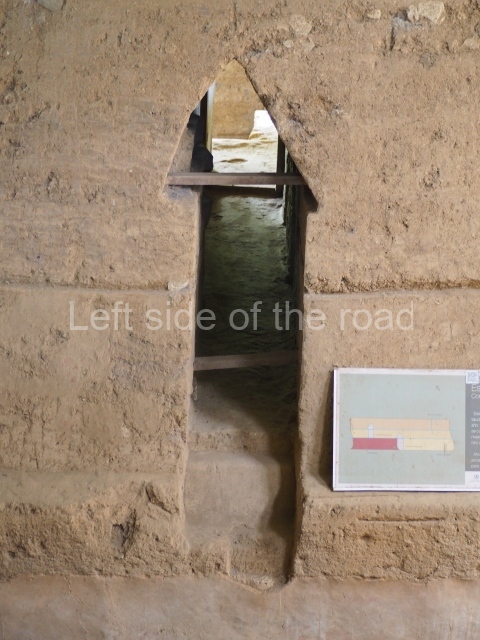

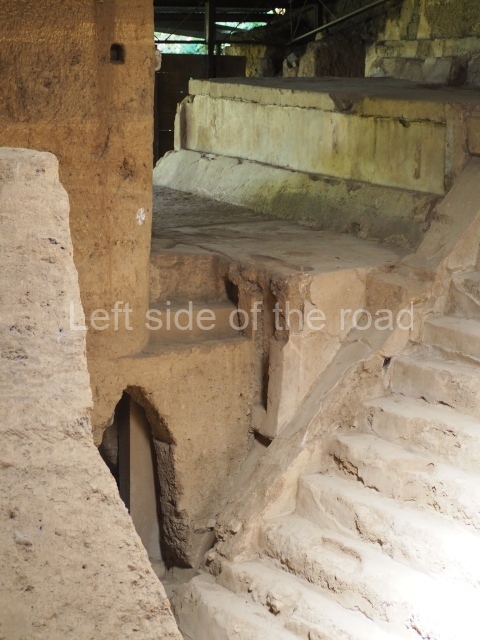

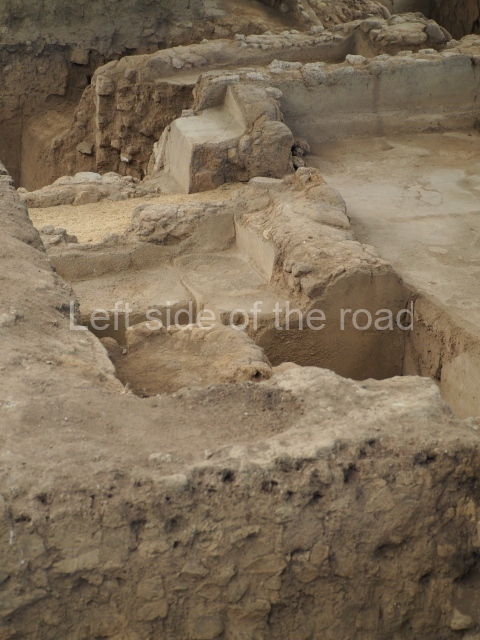

The Iximche citadel was articulated around various semi-enclosed plazas and platforms distributed in an area of approximately 15,000 sq m. It consisted of three principal elements: a temple, a large house and a ball court. It also contained various other details, such as altars, drainage systems, platforms for perishable structures, etc. Each section was connected by access stairways to the different plazas. There were also narrow passageways between the different groups to facilitate the circulation of the population. There were six plazas in total, all with a north-west/south-east orientation, varying slightly in size and containing over 170 structures all together. The plazas were designated archaeologically by means of the capital letters A to F, the largest being Plaza C. Only four of them have been restored. Watchtowers overlooking the surrounding ravines were built at the ends of the plateau on which the site stands. The main access, in the north-west, was preceded by a deep moat and flanked by two elongated structures in the fashion of a defensive wall, 3 m in height.

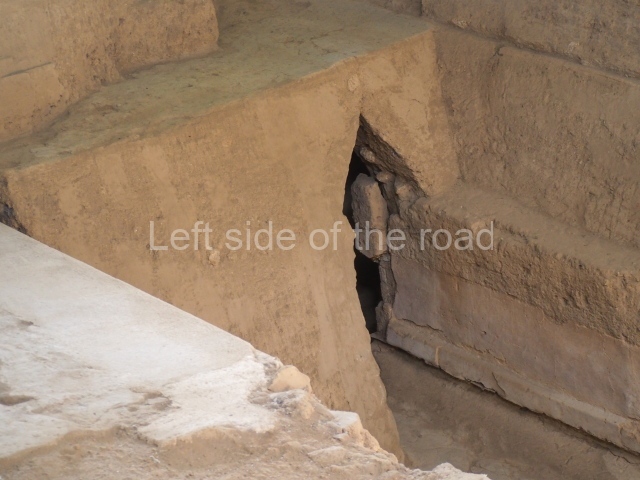

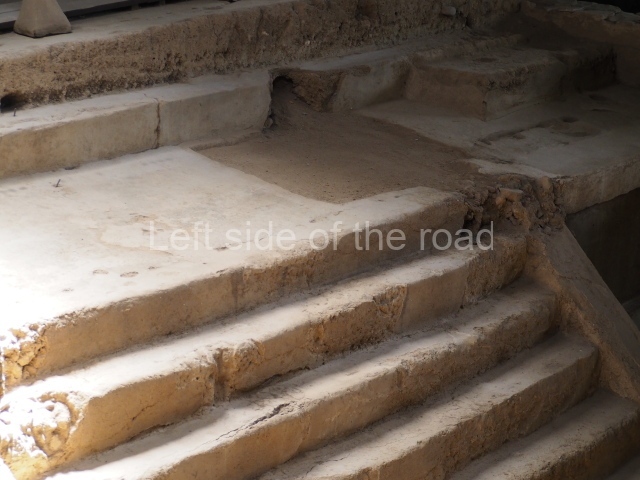

In terms of the construction materials, local resources such as sedimentary rock and pumice were used, cut into small blocks which were arranged in the fashion of ashlar stones, bonded by a mortar of sand, lime and clay and then covered with stucco. The interior of the structures was filled with mud and pebbles. Perishable materials were also used for walls and ceilings, mainly in the case of dwellings but some temples as well. The shape of the buildings varies according to their function. The temples are the most outstanding constructions and the tallest. They consist of a pyramidal platform with sloping walls and inset corners. A stairway is inset into the middle of the pyramid. At the top of the pyramid is a platform for supporting a construction made out of perishable material, in front of which there is usually a small altar. The facades of these buildings display vertical finial blocks, a characteristic feature of Postclassic architecture.

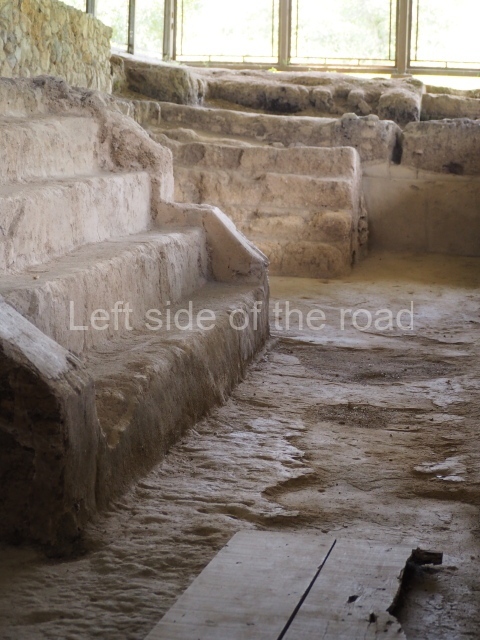

The ball-court structures are of the enclosed variety and were designed in the shape of the letter I. However, they have access stairways at both ends. The parallel volumes that delimit the court consist of a bench from which rises a vertical wall culminating in a type of platform. There are no visible butt or ring markers as at other sites in the highlands, although Guillemin mentions that various zoomorphic butts were found near structure 24 and may correspond to the missing markers. The total interior length of one of the courts (structure 8 ) is 30 m, with a width of 7 m between the walls, structure 7, another ball court which has not been restored, displays the same dimensions.

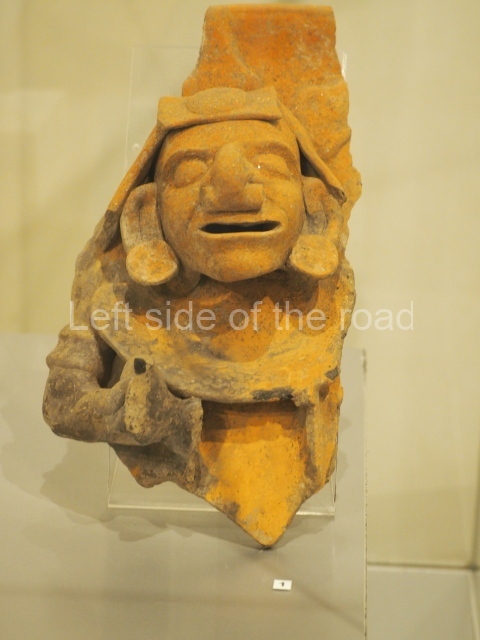

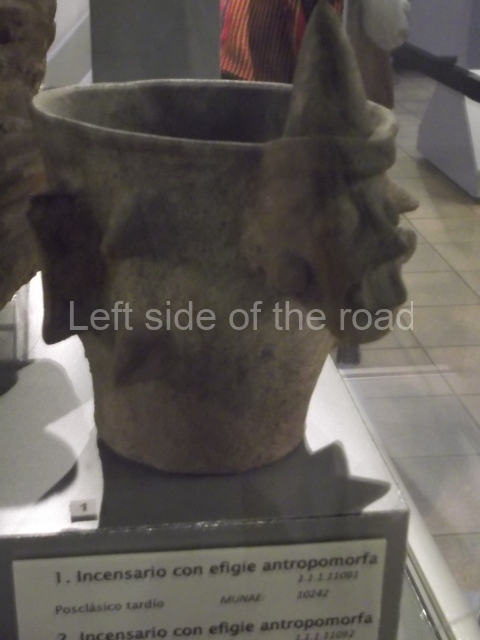

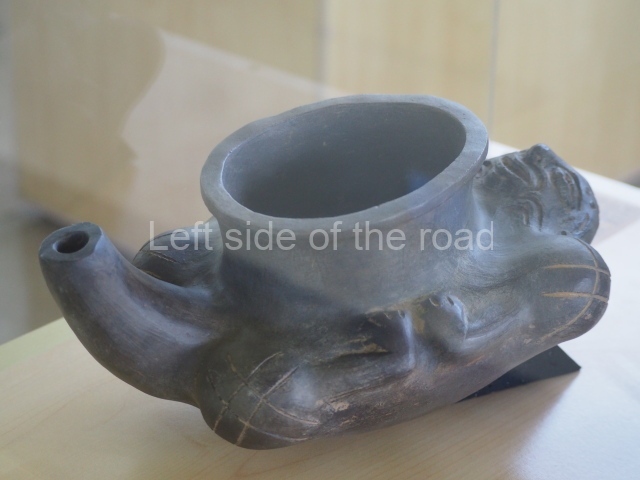

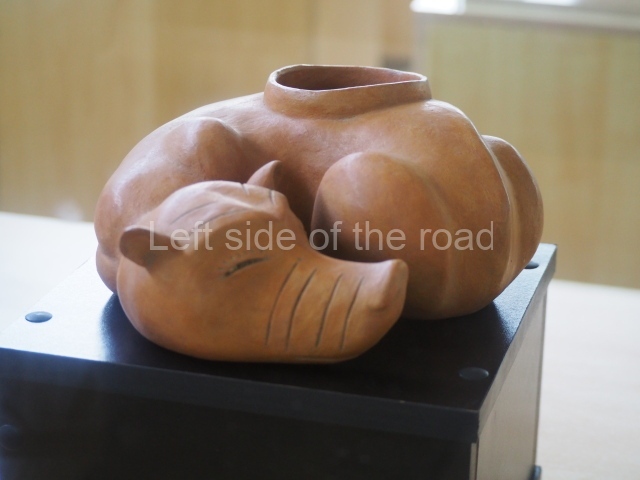

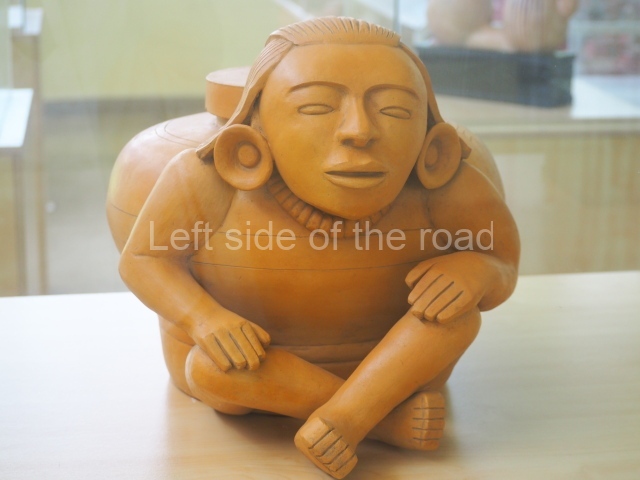

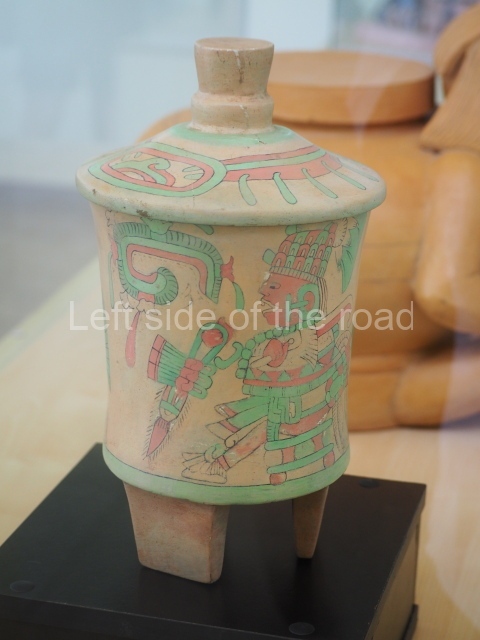

The so-called palace, situated in Plaza B, is the largest and most complex architectural structure at Iximche. According to Guillemin, the palace had an original core of approximately 500 sq m and was subsequently extended in all four directions, gaining new constructions with interior courtyards. It also extended upwards, eventually encompassing a surface area in excess of 3,000 sq m. The residential complex includes houses with interior benches and concave hearths, situated around enclosed courtyards with altars in the middle, structure 22 in Plaza A is an example of a large house; it consists of an elongated platform with numerous access stairways and what look like pillars forming the entrances to the interior of the building, which also contained abutted benches. In terms of the altars situated in the courtyards, these vary in shape and size; some of them consist of platforms that resemble miniature temples, while others have a circular plan. Plaza A has the largest number of such altars, six in total, with the majority situated opposite structure 3, a vast temple pyramid. Some of the most notable characteristics of Iximche are the murals that adorned the interior of various dwellings and buildings, as well as certain altars, such as Altar 47 next to structure 2, which displays traces of black, red and green paint. The plazas at the site were clearly associated with the residences of the most important lineages of the Caqchikel society of the 16th century. Plaza B may have accommodated the governors. Nowadays, Iximche has a site museum containing a collection of objects found during the excavations, as well as a scale model of the fortress city and photographs of the excavation process. It also has a car park, public toilets, information panels situated strategically along the itinerary, and wooded areas. Due to the sacred nature of the site, Maya ceremonies are conducted in a structure situated in the plaza furthest away from the entrance. Celebrated with a certain frequency, these rituals attract numerous people.

Edgar Carpio

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp490-492.

1. Plaza C; 2. Structure 7; 3. Plaza B; 4. Palace; 5. Structure 8; 6. Structure 22.

How to get there;

A combi, with the word Ruinas scrawled on the windscreen, leaves from the main square. It takes you straight to the main entrance to the site. Q5

GPS:

14d 44’ 8” N

90d 59’ 46” W

Entrance:

Q50