Maxim Gorky

More on the USSR

Culture, science, literature and art

Here is presented material that come under the very loose heading of ‘culture’ during the Socialist period of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Science

Dialectical Materialism and Historical Science, V. P. Volgin, Anglo-Soviet Journal, Winter 1949, 5 pages.

The origin of life on the Earth, A. I. Oparin, 3rd revised and enlarged edition in English translation, Academic Press, New York, 1957, 522 pages.

Soviet Marxism and Natural Science: 1917-1932, David Joravsky, Colombia University, New York, 1961, 446 pages. Includes a heavy focus on Marxist-Leninist philosophical topics.

Proletarian Science? The case of Lysenko, Dominique Lecourt, with an introduction by Louis Althusser, New Left Books, London, 1977, 165 pages.

Heredity and its variability, T.D. Lysenko, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 122 pages.

J.B. Lamarck, a materialist biologist, I.I. Prezent, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 56 pages.

Soviet biology, a report to the Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Moscow, 1948, T.D. Lysenko, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 82 pages.

The revisionist theory of the ‘Liberation’ of science from ideology, M.D. Kammari, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2022, 51 pages.

Science for Peace and Socialism, J.D. Bernal and Maurice Cornforth, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa, 2023, (originally Birch Books, London, 1949), 144 pages.

Psychological warfare in the strategy of Imperialism, V.L. Artemov, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2025, (originally Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, Moscow 1983), 140 pages.

Poetry

Popular poetry in Soviet Russia, George Z. Patrick, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1929, 298 pages.

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, a poem, in both Russian and English, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970, 208 pages.

Novels and short stories

Vasili Azhayev

Far From Moscow, Book 1, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 502 pages.

Far From Moscow, Book 2, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 462 pages.

Far From Moscow, Book 3, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 466 pages.

Konstantin Fedin

Early Joys, FLPH, Moscow, 1948, 503 pages.

No Ordinary Summer, Book 2, Progress, Moscow, 1950, 535 pages.

Dmitry Furmanov

Chapayev, FLPH, Moscow, 1955, 384 pages.

Alexei Fyodorov

The Underground R. C. carries on, Book 2, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 416 pages.

The Underground Committee carries on, Books 1 and 2, FLPH, Moscow, 1952, 518 pages.

Maxim Gorki

Creatures that once were men, Modern Library Publishers, New York, 1918 (originally), digital version 1998, 180 pages.

Fragments from my diary, McBride, New York, 1924, 320 pages.

Days with Lenin, Martin Lawrence, London, n.d., early 1930s?, 64 pages.

Maxim Gorky: writer and revolutionist, Moissaye J. Olgin, International, New York, 1933, 69 pages.

My childhood, Appleton-Century, New York, 1936, 374 pages.

And the others – a play, Unity Theatre Workshop, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 34 pages.

Lenin and Gorky, letters, reminiscences, articles, Progress, Moscow, 1973, 429 pages.

The city of the yellow devil, pamphlets, articles and letters about America (1906), Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977, 151 pages.

The Artamonovs, collected works in ten volumes, Volume 8, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982, 336 pages.

Literary Portraits, collected works in ten volumes, Volume 9, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982, 390 pages.

On Literature, collected works in ten volumes, Volume 10, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982, 455 pages.

The collected short stories of Maxim Gorky, edited by Avrham Yarmolinsky and Baroness Moura Budberg, Citadel Press, Secaucus, 1988, 403 pages.

Autobiography of Maxim Gorky (My Childhood, In the World, My Universities), n.p., n.d., 614 pages.

Maxim Gorky – a political biography, Tovah Yedlin, Praeger, Westport, 1999, 260 pages.

Culture and the people, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa, 2023, 229 pages.

Twenty six men and a girl, n.p., n.d., 11 pages.

Elmar Green

Wind from the South, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 292 pages.

Vassili Grossman

The Years of War, 1941-1945, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2025, (originally FLPH, Moscow, 1946), 575 pages.

Nikolai Ostrovsky

How the steel was tempered – Part 1, FLPH, Moscow, 1952, 312 pages.

How the steel was tempered – Part 2, FLPH, Moscow, 1952, 351 pages.

How the steel was tempered, Communist Party of Australia, Sydney, 2002, 312 pages.

How the steel was tempered, Progress, Moscow, n.d., 321 pages.

How the steel was tempered, picture book, Novosti, Moscow, 1983, 52 pages.

Vera Panova

Looking ahead, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 294 pages.

Konstantin Paustovsky

The Golden Rose – thoughts on the making of literature, FLPH, Moscow, 1950?, 285 pages.

Boris Pelovoi

A story about a real man, Progress, Moscow, 1973, 344 pages.

Alexander Serafimovich

The Iron Flood, International, New York, 1935, 248 pages.

Mikhail Sholokhov

Virgin Soil Upturned, the third volume in the Don Trilogy, Putman, London, 1937, 488 pages.

Mikhailo Stelmakh

Let the blood of man not flow, Progress, Moscow, 1975, 271 pages.

Alexei Tolstoy

Road to Calvary, Stalin Prize Novel, Hutchinson, London, 1941, 680 pages.

Aelita, FLPH, Moscow, nd.,167 pages.

Andrejs Upits

Outside Paradise and other stories, FLPH, Moscow, 1955, 363 pages.

Nikolai Virta

Alone – a novel, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 452 pages.

Various authors

Soviet Short Stories, FLPH, Moscow, 1947, 471 pages.

30 short stories, 1917-1967, Soviet Literature, No. 4, 1967, 224 pages.

Theatre

And the others – a play, Maxim Gorky, Unity Theatre Workshop, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 34 pages.

Art

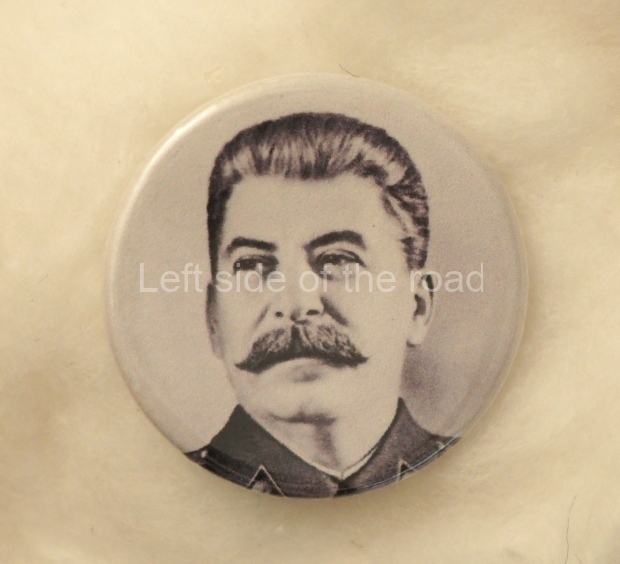

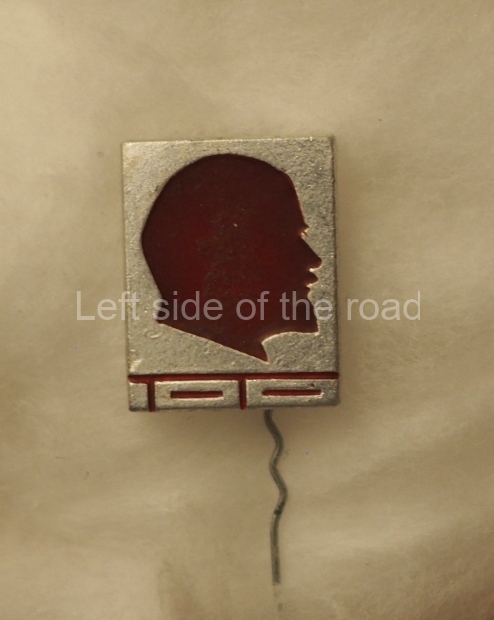

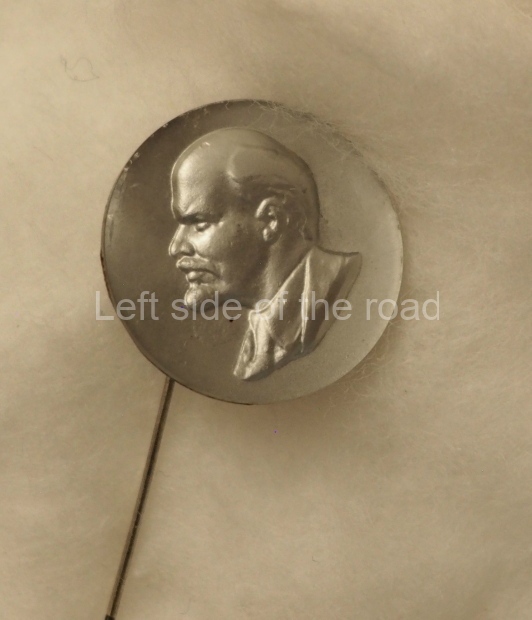

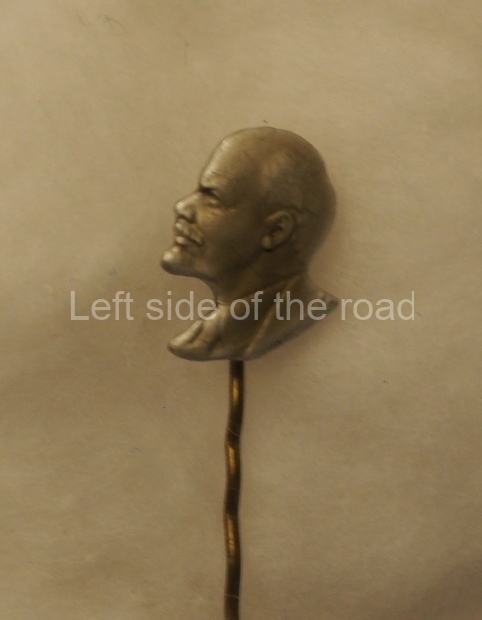

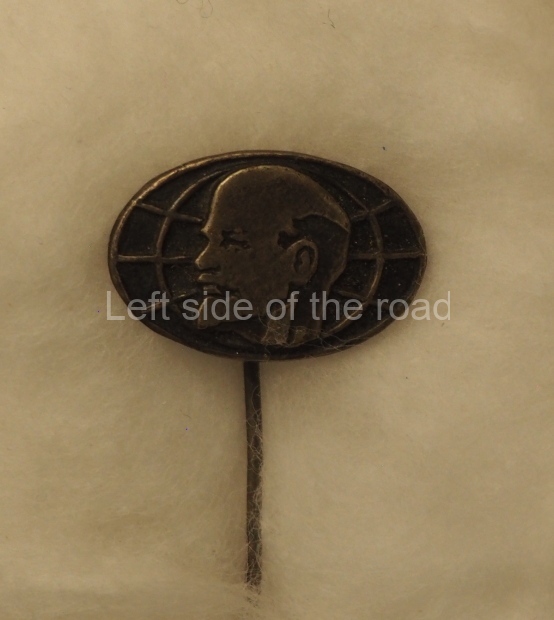

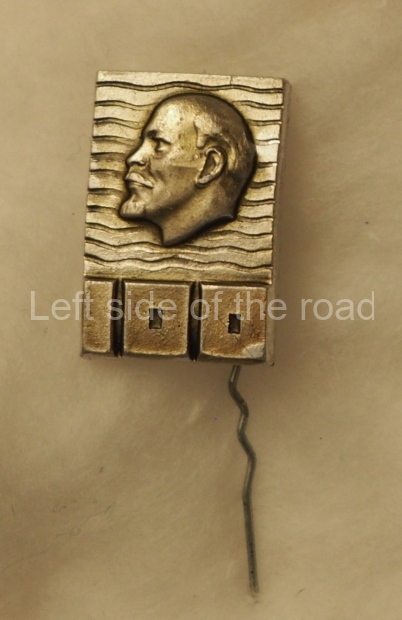

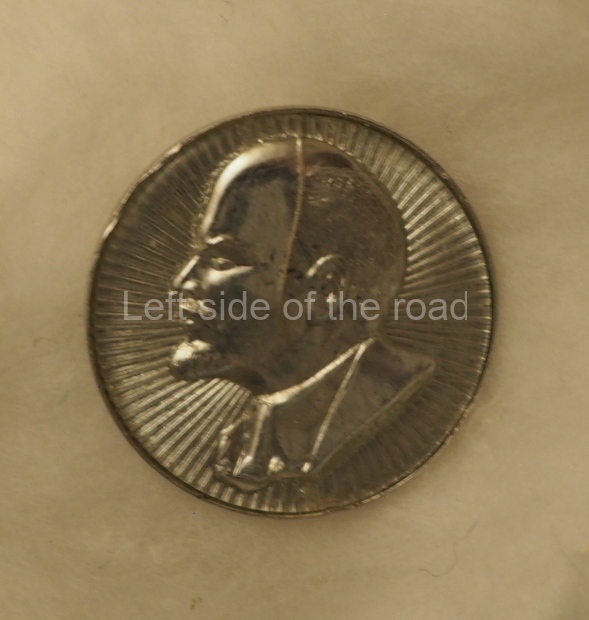

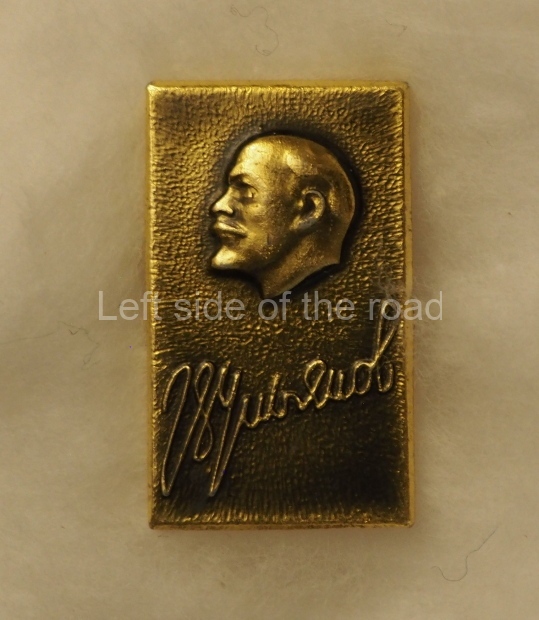

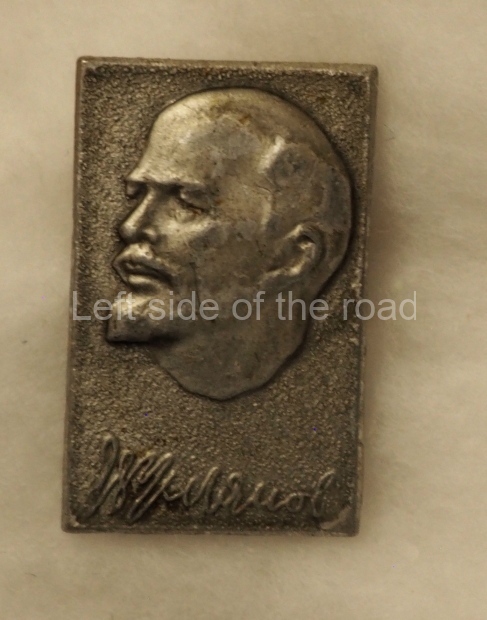

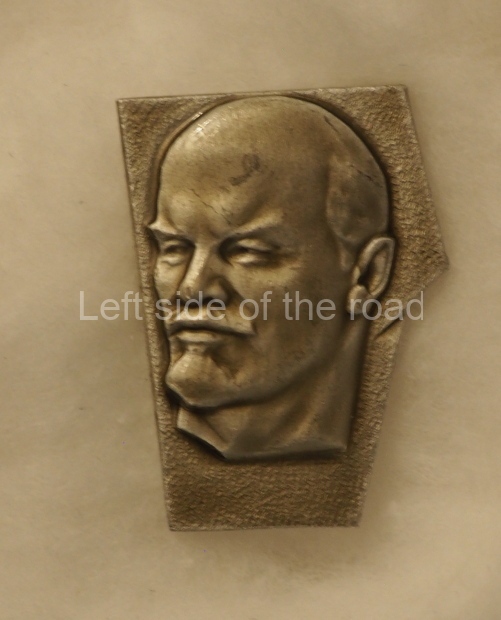

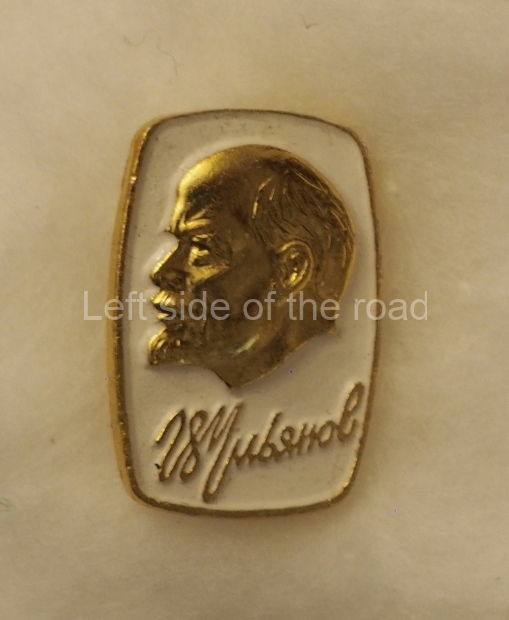

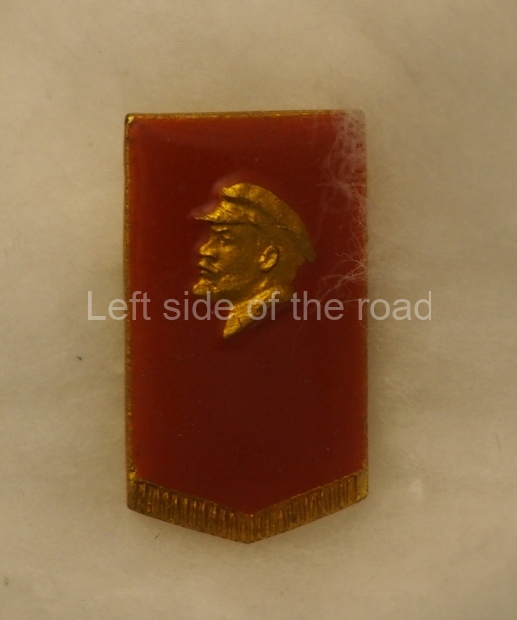

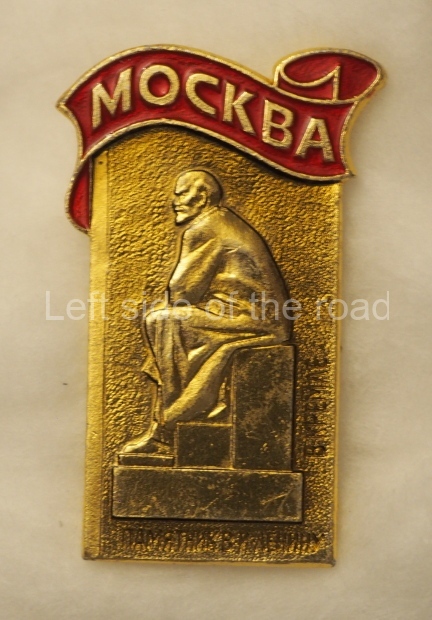

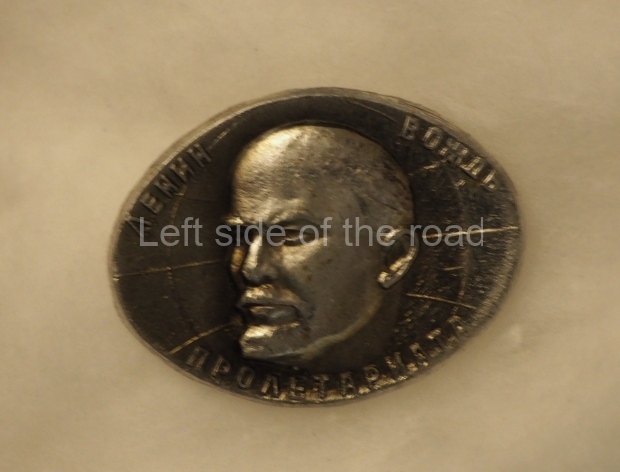

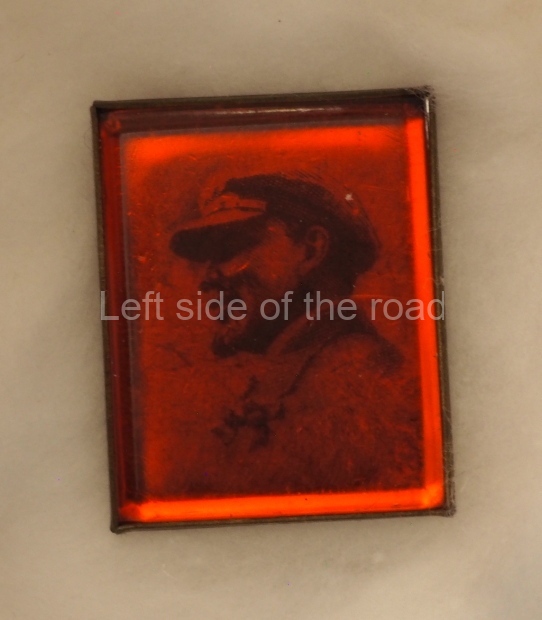

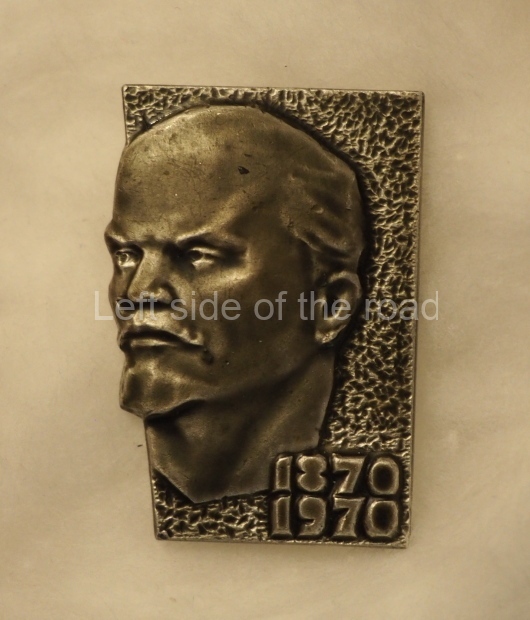

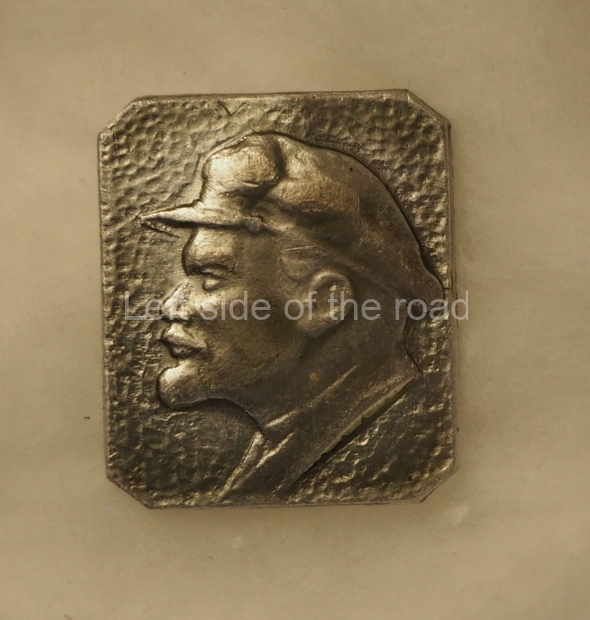

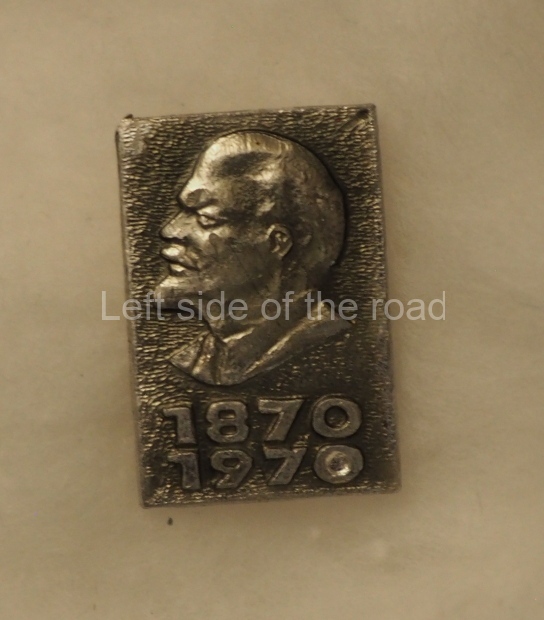

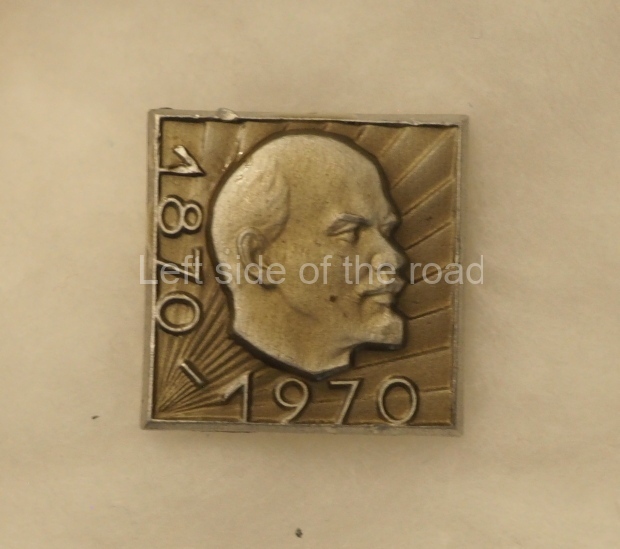

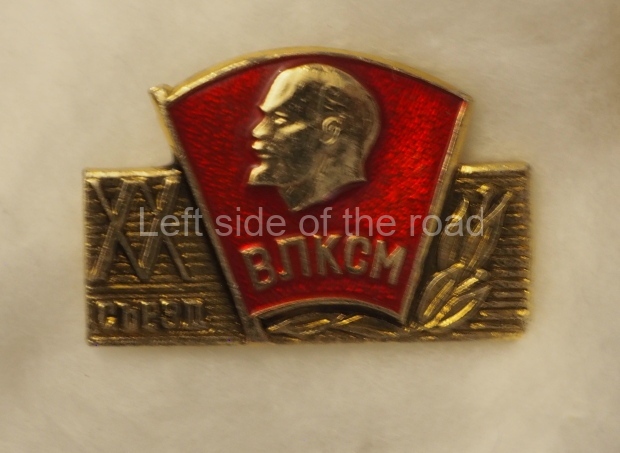

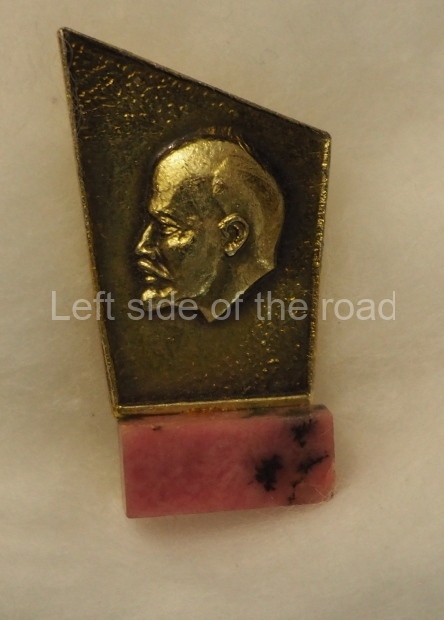

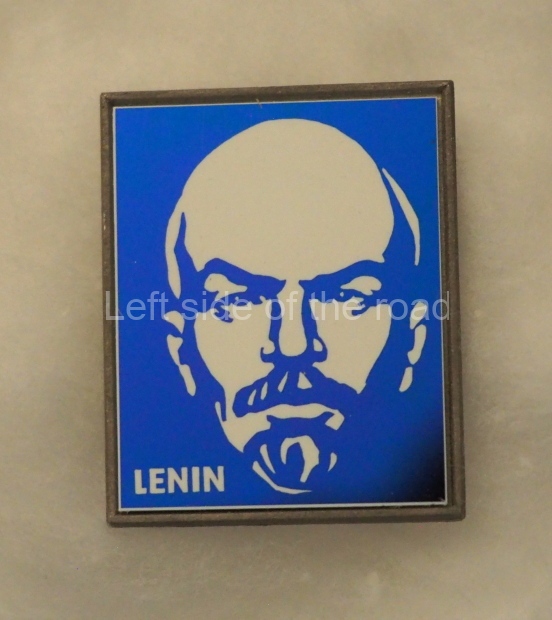

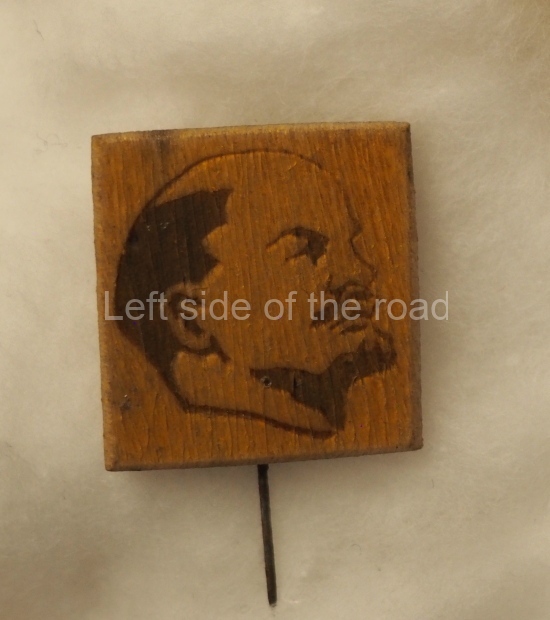

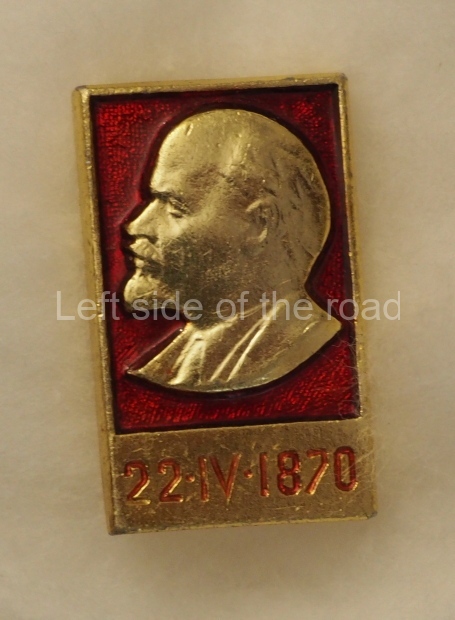

VI Lenin badge picture gallery

Russian art of the avant-garde theory and criticism, 1902-1934, ed John E. Bowlt, Viking, New York, 1976, 360 pages. [A lot of scribblings throughout but the text, in the main, remains legible.]

Art of the Avant Garde in Russia, selections from the George Costakis Collection, Margit Rowell and Angelica Zander Rudenstine, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1981, 320 pages.

The Russian avant-garde book 1910-1934, ed. Margit Rowell and Deborah Wye, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, 304 pages.

The Russian avant-garde and radical modernism, an introductory reader, ed. Dennis Ioffe and Frederick White, Boston, 2012, 486 pages.

Museums and Art Galleries

The Central Lenin Museum, Moscow – a guide. (Moscow, Raduga, 1986), 160 pages. A guide to the now destroyed Museum dedicated to the life and work of VI Lenin.

The Stalin Museum in his birthplace of Gori, in the centre of Georgia, is one of the few places in the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) where you will see any reference (let alone a positive reference) to the leader of the world’s first socialist state.

The SM Kirov museum is located in the famous ‘House of Three Benois’ on the second entrance of the house number 26/28 on Kamennoostrovsky Prospect, on the 4th and 5th floors, in Leningrad (Saint Petersburg).

Probably the largest and most extensive art gallery in the world is that which spans the whole of the central area of Moscow. This art gallery doesn’t have just one entrance but dozens and although you have to pay it’s also one of the cheapest in Europe. This art gallery can be crowded, very crowded, at certain times of the day but the arrival of people comes in waves so not a total inconvenience. It’s also the world’s biggest gallery of Soviet Socialist Realist Art – the name of this gallery is the Moscow Metro.

The Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park, in Moscow is the collection of monuments and statues of the Socialist period that used to be found throughout the city.

Park Pobeda – Victory Park – exhibition and museum, Moscow.

Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy (VDNKh) – Moscow. A huge park on the outskirts of the city which originally provided an opportunity for visitors to understand the successes of Socialism throughout the whole of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Socialist Realist Art in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Art galleries in the Central Asian former Soviet Republics.

Frunze Museum – Bishkek – Kyrgyzstan. The Frunze museum was originally opened in December 1925, centred on the small house where he was born. This house is now a feature on the ground floor of the modern building.

JV Stalin Museum – Mamayev Kurgan – Stalingrad. This is a very strange museum – not to what it is dedicated – but for its location and very existence. Mamyev Kurgan is probably the most revered war memorial in the whole of the Soviet Union/Russia – and that would include those Republics which broke away amidst the chaos of the early 1990s. And yet just a few hundred metres behind the mammoth statue is a private hotel and restaurant which just happens to have a small, three room museum to JV Stalin in the basement.

Tashkent Metro – Uzbekistan. The Tashkent Metro was a relatively late addition to the Soviet Union’s mass transit system being the seventh to be completed in 1977. The system followed many of the conventions established since 1935 in Moscow; the design of the station platforms; the style (if not the content) of the decoration; the use of light to give the impression of not being underground; the use of the finest materials; and the method in moving people through the system as fast as possible

Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR/Central Armed Forces Museum – Moscow. The main reason I wanted to go to the Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR/Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow was because I had learnt that it was there that the Nazi banners that had been thrown into the mud at the base of the Lenin Mausoleum (with Comrade Stalin accepting them on behalf of the Soviet people) on the first Victory Day on May 9th, 1945, were presently on display.

Central Pavilion – Tretyakov Gallery Exhibition – VDNKh. The principal pavilion in the VDNKh park has undergone a major renovation and it has been brought back (almost) to what it was like when it opened in 1954. Some of the original works have been ‘lost’ – perhaps only mislaid as a number of art works considered ‘lost’ have subsequently been found – but a number that had been distributed to other galleries have been returned.

VI Lenin Exhibition at the State History Museum, Moscow. At the moment there’s a special exhibition attached to State History Museum, one which documents some of the life and work of VI Lenin. However, there’s only a fraction on display here of what used to be on show in the now closed Central Lenin Museum (which used to be housed in what is now the War of 1812 Museum).

The Central Lenin Museum, Moscow – a guide. Raduga, Moscow, 1986, 160 pages. A guide to the now destroyed Museum dedicated to the life and work of VI Lenin.

Architecture

Moscow – Architecture and Monuments, M Ilyin, Progress, Moscow, 1968, 253 pages.

Soviet Architectural Avant-Gardes – Architecture and Stalin’s Revolution from Above, 1928-1938, Danilo Udovicki-Selb, Bloomsbury, London, 2020, 360 pages.

Moscow Monumental – Soviet Skyscrapers and Urban Life in Stalin’s Capital, Katherine Zubovich, Princetown University Press, Princetown, 2021, 428 pages.

Art in everyday circumstances

Soviet Advertising Posters 1917-1932, Moscow, 1972, 127 pages.

The debate on Soviet Culture

VOKS Bulletin, No 63, USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, Moscow, 1950, 96 pages.

A few of the articles:

Concerning Marxism in Linguistics, J. Stalin.

Increasing Stability of the Rouble – A Law of the Soviet Economy, I. Konnik

The Twelve Apostles, Sergei Eisenstein

British-Soviet Friendship, Dr. Hewlett Johnson, Dean of Canterbury

Soviet Russian Literature: 1917-1950, Gleb Struve, University of Oklahoma Press, 1951, 431 pages. Has some underlining. The author is harshly anti-Communist, but this book discusses the early literature of Soviet Russia quite thoroughly.

Literature under Communism: the literary policy of the CPSU from the end of World War II to the death of Stalin, Avrahm Yarmolinsky, Indiana University: Russian and East European Series, vol. XX, n.d. (c. 1957), 178 pages. Anti-Communist perspective.

Early Soviet writers, Vyacheslav Zavlishin, Research Program in USSR, Praeger, New York, 1958, 472 pages. Another anti-Communist book, but with some hard-to-find information about Soviet writers.

On literature, music and philosophy, AA Zhadanov, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1950, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2022, 112 pages.

‘Mass culture’ in the USA and the problem of the individual, E.N. Kartseva, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2025, (originally Nauka Publishing House, Moscow 1974), 233 pages.

More on the USSR